Abstract

This study aimed to systematically review and describe the evidence on chlamydia and gonorrhoea reinfection among men, and to evaluate the need for retesting recommendations in men. PubMed and STI conference abstract books from January 1995 to October 2006 were searched to identify studies on chlamydia and gonorrhoea reinfection among men using chlamydia and gonorrhoea nucleic acid amplification tests or gonorrhoea culture. Studies were categorised as using either active or passive follow‐up methods. The proportions of chlamydial and gonococcal reinfection among men were calculated for each study and summary medians were reported. Repeat chlamydia infection among men had a median reinfection probability of 11.3%. Repeat gonorrhoea infection among men had a median reinfection probability of 7.0%. Studies with active follow‐up had moderate rates of chlamydia and gonorrhoea reinfection among men, with respective medians of 10.9% and 7.0%. Studies with passive follow‐up had higher proportions of both chlamydia and gonorrhoea reinfections among men, with respective medians of 17.4% and 8.5%. Proportions of chlamydia and gonorrhoea reinfection among men were comparable with those among women. Reinfection among men was strongly associated with previous history of sexually transmitted diseases and younger age, and inconsistently associated with risky sexual behaviour. Substantial repeat chlamydia and gonorrhoea infection rates were found in men comparable with those in women. Retesting recommendations in men are appropriate, given the high rate of reinfection. To optimise retesting guidelines, further research to determine effective retesting methods and establish factors associated with reinfection among men is suggested.

Chlamydia and gonorrhoea are the two most common bacterial sexually transmitted infections (STIs) in the US, with 929 462 (319.6 per 100 000 population) and 330 132 (113.5 per 100 000 population) reported cases, respectively, in the US and district of Columbia during 2004.1 Serious complications associated with chlamydia and gonorrhoea include chronic pelvic pain, infertility, ectopic pregnancy and pelvic inflammatory disease in women, as well as proctitis and epididymitis in men.2,3,4,5,6 Although the treatment efficacy of first line drugs for both chlamydia and gonorrhoea infection is high,2,3,7,8,9,10,11 the problem of reinfection remains.2,3,12

The prevalence of recurrent chlamydial infection is especially well documented in young and unmarried women, ranging between 6% and 23% within 6 months of treatment.13,14,15,16,17,18,19 As a result, the 2002 US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention treatment guidelines recommended that all women with chlamydial infection be tested for reinfection (different from test of cure) at 3–4 months after treatment.20 Although some local health departments recommend retesting men for STIs, there are no established national retesting guidelines for either gonococcal infection in women, or chlamydial or gonococcal infection in men, partly owing to the limited data available for guideline development.

In the US, there has been a 46.6% increase in reported cases of chlamydia in men from 1999 to 2004,1 probably as a result of increased screening and diagnoses of chlamydial infections with the advent of highly sensitive and non‐invasive nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs). Although incident chlamydia tends to be higher in women,1 some recent studies have found that the prevalence of chlamydial infection in young men is comparable with that of young women at 7–15%.21,22,23,24,25,26,27

Focusing screening and treatment only on women will not effectively reduce the overall prevalence of both chlamydia and gonorrhoea in the US because their male partners might remain infected.2,3,25,28 Given that untreated male partners are a likely source of reinfection among women following treatment and that men exhibit high rates of asymptomatic infections, it is important to evaluate the need for extending screening guidelines for chlamydial and gonococcal reinfection to men as a means of reducing recurrent chlamydial and gonococcal infection in both men and women. Although several studies implementing expedited partner treatment (EPT) have demonstrated significant decreases in reinfection among women, a considerable proportion of reinfection occurred despite treating existing partners.29,30 Thus, retesting men might be another important prevention strategy.

Earlier literature from the 1970s and 1980s has examined the role of retesting in reducing morbidity from gonococcal reinfection during those decades.31,32,33,34 However, there is no recent compilation of the literature about gonococcal reinfection in men and no review has been published to date about chlamydial reinfection in men. We systematically reviewed and described the current evidence of recurrent chlamydial and gonococcal infection among men, focusing on studies using the most sensitive and specific tests. Our results might be useful in developing retesting guidelines for men.

Methods

We searched for published or presented scientific literature regarding chlamydial and gonococcal infection, reinfection, retesting and screening recommendations for men. Using PubMed, we used combinations of search terms including “repeat gonorrhea chlamydia”, “recurrent gonorrhea chlamydia”, “repeat gonorrhea”, “repeat chlamydia”, “persistent gonorrhea”, “persistent chlamydia”, “rescreening gonorrhea”, “rescreening chlamydia”, “retesting gonorrhea” and “retesting chlamydia” to find literature published between January 1995 and October 2006. Literature from previous decades was excluded because of differences between current and past disease trends. We searched for scientific abstracts from the US and International STI conferences from January 2000 to August 2006. For relevant conference abstracts, actual posters and/or presentations were reviewed to facilitate data abstraction. To maximise the search, we examined the articles of people known to be involved in the research of chlamydia and gonorrhoea and searched the bibliographies of relevant papers. Finally, we contacted eight authors of relevant articles to acquire any unpublished data.

All studies included men and reported chlamydia, gonorrhoea, or chlamydia and gonorrhoea combined data as well as gender‐specific data. Included studies also had a follow‐up period starting at least 2 weeks after treatment of initial infection and used NAATs for chlamydia and NAATs or culture for gonorrhoea to ensure consistent sensitivity and specificity of test results. There is a significant difference in test performance of chlamydia NAATs and of older tests for chlamydia,2,35 but little difference between gonorrhoea NAATs and gonorrhoea culture.2,36,37 However, studies varied in whether there were age restrictions for their participants or restrictions by gender of partners. Several studies were excluded for not including gender‐specific data,38 not restricting to laboratory‐confirmed chlamydia and/or gonorrhoea at baseline39 and not including organism‐specific data.40,41,42

Studies were classified on the basis of the follow‐up method: active follow‐up as in a prospective cohort study design versus passive follow‐up through disease or clinic registries. To standardise reported measures, we calculated the overall proportion of reinfected individuals and defined it as the number of reinfected individuals per followed‐up enrollees. Data abstracted from studies were summarised in tables. We report the median as the measure of central tendency to account for the variation in studies, and also report the range. We plotted estimates of proportions of reinfection by study.

Results

Our initial search of PubMed returned 71 articles for “repeat gonorrhea chlamydia”, 19 articles for “recurrent gonorrhea chlamydia”, 53 articles for “repeat gonorrhea”, 108 articles for “repeat chlamydia”, 51 articles for “persistent gonorrhea”, 417 articles for “persistent chlamydia”, 5 articles for “rescreening gonorrhea”, 9 articles for “rescreening chlamydia”, 6 articles for “retesting gonorrhea” and 31 articles for “retesting chlamydia.” Numerous duplicates were found among the various search terms. Of these, 12 published articles tested men and met our inclusion criteria of having a follow‐up period and using NAATs for chlamydia testing and using NAAT or culture for gonorrhoea testing.29 In addition, one presentation and one poster from national and international STI conferences met our inclusion criteria.43,44 Reviewed studies were published or presented between 2000 and 2006, with data collected from 1992 to 2004. Tables 1 and 2 provide a select summary of the 14 reports.29,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,5657

Table 1 Data abstracted from studies with active follow‐up of chlamydial and gonococcal reinfection among men.

| Author, year (reference) | Population | n | Follow‐up method | Follow‐up period | % of enrolled men with follow‐up (n) | % of men with repeat chlamydia (n) | % of men with repeat gonorrhea (n) | % of men with repeat gonorrhoea/chlamydia (n) | % of female data (n) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peterman et al, 200645 | STD, clinic‐based; Newark, Denver and Long Beach: chlamydia and/or gonorrhoea‐infected subset of 2419 clinics, patients aged 15–39 years, enrolled in HIV prevention counselling study | 246 M, 133 F | Scheduled 3 month follow‐up visit at respective STD clinic | 3 months* | 83.3 (205/246) | 9.8 (112) | 14.9 (68) | 20.0† (25) | CHLAMYDIA: 10.7 (84) GONORRHOEA: 3.6 (30) |

| Bernstein et al, 200646 | STD, clinic‐based; Baltimore, Maryland: people diagnosed as having gonorrhoea at public STD clinic | 548 M, 119 F | Scheduled follow‐up visit or follow‐up by disease investigation specialists | 3 months | 24.3 (133/548) | NA | 30.8 (41/133) | NA | GONORRHOEA: 28.9 (13/45) |

| Ellen et al, 200647 | Various venues; Baltimore and Denver: asymptomatic chlamydia and/or gonorrhoea infected males aged 13–25 years | 314 M | Scheduled follow‐up visits at 1 and 4 months | 4 months | 44.3‡ (139/314) | NA | NA | 6.5§ (9/139) | NA |

| Golden et al, 200543 | Population based; King County, Washington: partner‐notified heterosexuals who returned mailed rescreening kits | 57 M, 124 F | Mailed retesting kit 3 months after treatment | 3 months | 35.8¶ (221/618) | 10.7 (6/56) | 0.0 (0/14) | NA | CHLAMYDIA: 7.6 (11/144) GONORRHOEA: 16.7 (2/12) |

| Golden et al, 200529 | Population based; King County, Washington: gonorrhoea and/or chlamydia‐infected women and heterosexual men with untreated partners | 646 M, 2105 F | Reinterview and retest | 19 weeks | 61.3 (396/646) | 10.1 (27/267) | 7.0 (11/157) | 9.1‡ (37/396) | CHLAMYDIA: 12.3 GONORROHEA: 7.0 CHLAMYDIA/GONORROHEA: 12.0 |

| Sparks et al, 200448 | STD, clinic based; King County, Washington: asymptomatic chlamydia and/or gonorrhoea infected heterosexual males and females aged ⩾14 years | 84 M, 38 F | Mailed or clinic retesting 10–24 weeks after treatment | 24 weeks | 63.4 (71/112) | 16.0 (6/38) | 0.0 (0/9) | NA | CHLAMYDIA: 0 (0/20) GONORRHOEA: 25 (1/4) |

| Dunne et al, 200444 | Various venues; Baltimore, Denver and San Francisco: chlamydia‐infected men | 361 M | Scheduled follow‐up visits at 1 and 4 months | 4 months | 76.0 (272/358) | 11.4 (31/272) | NA | NA | NA |

| Kjaer et al, 200049 | Population based; Ringkjobing, Denmark: chlamydia‐infected general practice patients aged ⩾18 years who had not been treated with antibiotics in previous 4 weeks | 12 M, 30 F | Serial mailed specimens collected at 2, 4, 8, 12 and 24 weeks | 24 weeks | 83.3** (10/12) | 11.1†† (1/9) | NA | NA | 12.0‡‡ (3/25) |

F, female; M, male; NA, not applicable; STD, sexually transmitted disease.

*Follow‐up period was for 1 year, but abstracted data are limited to first follow‐up at 3 months.

†Repeat chlamydia/gonorrohea defined as either chlamydial or gonococcal infection in men coinfected with chlamydia and gonorrhoea at baseline.

‡Follow‐up is defined as participants with at least one follow‐up visit. If 1‐month visit was not available, 4‐month visit was used.

§Repeat chlamydia/gonorrohea defined as chlamydial infection at follow‐up in men with chlamydia at baseline or gonococcal infection at follow‐up in men with gonorrhoea at baseline.

¶Measure is overall follow‐up rate. Male‐specific data were not available.

**Defined as at least one mailed specimen collected 2–24 weeks after baseline mailed specimen.

††Reported reinfection data are defined as a new infection between 2 and 12 weeks after initial infection.

‡‡Repeat chlamydia/gonorrohea defined as chlamydia infection at follow‐up in men with chlamydia at baseline or gonococcal infection at follow‐up in men with gonorrhoea at baseline or either infection in men coinfected with chlamydia and gonorrhoea at baseline.

Table 2 Data abstracted from studies with passive follow‐up of chlamydial and gonocaccal reinfection among men.

| Author, year (reference) | Population | n | Repeat case definition | % of men with repeat chlamydia (n) | % of men with repeat gonorrhoea (n) | % of men with repeat gonorrhoea/CHLAMYDIA(n) | % of female data (n) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gunn et al, 200450 | Population based; San Diego County, California: people with reported cases of gonorrhoea | 6243 M, 4747 F | 1/1995–12/2001: ⩾2 gonococcal infections for same name and DOB within 30–365 days time frame and trailing 12‐month repeats | NA | 5.0 (311/6243) | NA | GONORRHEA: 4.1 (196/4747) |

| Lee et al, 200451 | STD clinic based; Portsmouth, UK: men and women diagnosed as having chlamydia | 214 M, 861 F | 9/1999–8/2000: subsequent chlamydia at any visit within a 3‐year follow‐up period | 16.4 (10/61) | NA | NA | CHLAMYDIA: 20.5(46/224) |

| Mehta et al, 200352 | STD clinic based; Baltimore, Maryland: heterosexuals ⩾12 years diagnosed as having gonorrhoea | 1717 M, 6610 F | 1/1994–10/1998: first incident gonococcal infection at least 3 months after initial visit to a maximum of 4.8 years | NA | 11.9 (788/6610) | NA | GONORRHOEA: 7.1 (122/1717) |

| Rietmeijer et al, 200253 | STD clinic based; Denver, Colorado: patients screened for chlamydia more than once | 2097 M, 1470 F | 1/1997–6/1999: more than one positive chlamydia test >30 days apart | 18.3 (56/306) | NA | NA | CHLAMYDIA: 23.2 (43/185) |

| Gunn et al, 200054 | STD clinic based; San Diego County, California: patients with a new STD or a history of STD in the past 5 years | 2612 M | 2–7/1995: subsequent STD reported by a client or communicable disease investigator between 45 and 365 days after treatment | NA | NA | 6.3 (39/620) | CHLAMYDIA/GONORRHOEA: 6.3 (15/239) |

| Thomas et al, 200055 | STD clinic based; Step County, North Carolina: patients diagnosed as having chlamydia and/or gonorrhoea | 626 M, 574 F | 8/1992–1/1994: subsequent chlamydial and/or gonococcal infection in clinic or private practice >14 days and <17 months after index infection | NA | NA | 28.3 (177/626) | GONORRHOEA/CHLAMYDIA: 19.0 (109/574) |

DOB, date of birth; F, female; M, male; NA, not applicable; STD, sexually transmitted disease; STI, sexually transmitted infection.

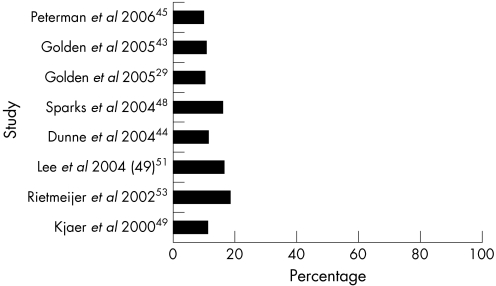

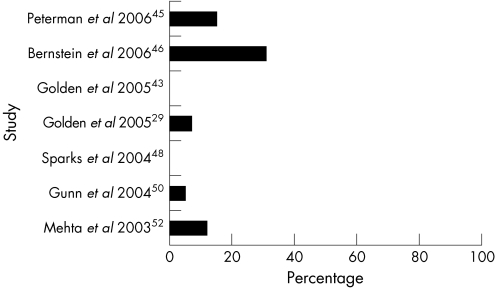

Of the 14 studies, 5 investigated both chlamydial and gonococcal reinfections, 4 studied only chlamydial reinfection and 3 studied only gonococcal reinfection. The proportion of men with repeat chlamydia ranged from 9.8%45 to 18.3%,53 with a median of 11.3% (fig 1). The proportion of men with repeat gonorrhoea ranged from 0%43,48 to 30.8%,46 with a median of 7.0% (fig 2).

Figure 1 Percentage of chlamydial reinfection among men by study.

Figure 2 Percentage of gonococcal reinfection among men by study.

Follow‐up periods for the studies with active follow‐up ranged from 10 weeks48 to 24 weeks,49 with a median of 4 months. By contrast, the studies with passive follow‐up allowed for repeat infection definitions up to a maximum of 4.8 years52 from initial infection. The studies with active follow‐up had moderate proportions of repeat chlamydia and gonorrhoea among men, with respective medians of 10.9% and 7.0%. Follow‐up rates to obtain these estimates ranged from 24.3%46 to 83.3%,45,49 with a median of 62.4%. The studies with passive follow‐up had higher proportions of both chlamydial and gonococcal reinfection among men, with respective medians of 17.4% and 8.5%. The follow‐up rate of the studies using passive follow‐up was indeterminable.

In the studies accounting for infection in both sexes, the proportions of repeat chlamydia and gonorrhoea among men were comparable to those among women. The proportions of chlamydial reinfection among males was only slightly lower,29,45,49,50,53 and in two studies higher,43,48 than those among women. A study in three major US cities with active follow‐up by a scheduled 3‐month STD clinic visit found a repeat chlamydia proportion among men at 9.8% comparable with that among women at 10.7%.45 A study with passive follow‐up found a similar trend with a chlamydial reinfection proportion among men at 18.3% only slightly lower than that among women at 23.2%.53

The proportions of repeat gonorrhoea among men were either nearly equal29 or slightly above those among women.46,50,52 A study with active follow‐up by scheduled clinic visit or disease investigation specialist found a repeat gonococcal infection proportion among men at 30.8% to be slightly higher than that among women at 28.9%.46 Similarly, a passive study found gonorrhoea among men at 5.0% to be greater than that among women at 4.1%.50

Some studies only presented combined chlamydial or gonococcal reinfection data. In these studies, combined chlamydial or gonococcal reinfections among men were either equal to54 or even higher than those among women.55 One study with passive follow‐up in North Carolina found repeat infection among men to be higher than that among women, with respective reinfection proportions of 28.3% and 19.0%.55

One study specifically focused on the effect of treatment of partners on reinfections rates and showed that increased treatment of partners reduced the amount of chlamydial and gonococcal reinfection among men.29 This study found that with standard referral, repeat chlamydia among men and women was nearly equivalent at 12% and 13%, respectively, and with EPT, repeat chlamydia among men at 7% was lower than that in women at 11%.

Analysis of factors associated with chlamydial and gonococcal reinfection among men found that a history of STIs was consistently predictive of reinfection with either or both infections.44,45,54,55 Reinfection in either sex was also strongly associated with having untreated partners43,45,46,50 and the demographic factors of younger age29,50,52,53,55 and non‐white race.45,55 High‐risk sexual behaviour, including not using condoms, change in partners and higher number of sexual partners inconsistently, was associated with an increased risk for repeat infection.29,45,51,52

Discussion

The reviewed studies provide strong evidence for the substantial incidence of chlamydial and gonococcal reinfection among men. The proportions of repeat chlamydial infection among men had a median of 11.3% and ranged from 9.8% to 18.3%. Proportions of repeat chlamydia among men were similar to those among women. Such data are especially significant because current retesting guidelines only recommend chlamydia rescreening in women 3 months after initial infection.20 Although initial incident chlamydial infection may be higher in women than in men,1 probably due to shorter duration of natural clearing of infections in men, the reinfection data suggest that chlamydial reinfection rates among men are similar to those among women, and may contribute to continued infections in women.

The proportions of repeat gonococcal infection among men in the reviewed studies had a median of 7.0% and ranged from 0% to 30.8%. Proportions of repeat gonococcal infection among men were similar to those among women. There are currently no gonorrhoea retesting guidelines for either men or women, probably owing to the decreased reported national incidence of gonorrhoea and more limited recent data about reinfection. Because the studies we reviewed indicated that proportions of repeat gonococcal infection among men are equal if not higher than those of repeat chlamydia among women, retesting men after initial treatment might be effective in reducing the prevalence of gonorrhoea among both men and women.

A history of STIs and the demographic factors of younger age and non‐white race were strongly associated with chlamydial and gonococcal reinfection. Data from the studies indicate an inconsistent association between reinfection and risky sexual behaviours such as increased number of partners and not using condoms. Because no specific behavioural factors predict reinfection, all chlamydia‐ or gonorrhoea‐infected men should be retested for reinfection.

Certain factors limited the findings of this review. The search strategy could have possibly overlooked relevant studies, although numerous steps were taken to prevent this oversight. The search on PubMed was limited to English‐only sources, thus possibly excluding studies from non‐English‐speaking countries with high prevalences of chlamydia. Most importantly, there is little published literature documenting repeat chlamydial and gonococcal infection.

Major discrepancies in reported reinfection proportions were due to the variation of study designs. The studies had either active or passive follow‐up in their design and so used a wide range of different follow‐up periods. The longer follow‐up periods for many passive studies compared with active follow‐up studies (years vs months) allowed more people to become reinfected with time, yielding higher median reinfection proportions in passive studies than in active follow‐up studies. In addition, all study designs might be affected by a differential return for follow‐up among symptomatic and asymptomatic individuals. Given that symptomatic people are more likely to return than asymptomatic people, this would cause an overestimate of the true rate of reinfection. Studies with passive follow‐up, which depend on people seeking services, are especially vulnerable to this bias.56 In addition, the studies with active follow‐up experienced variable follow‐up rates ranging from 24.3% to 83.3%, which may also differentially account for asymptomatic infections.

Although current recommended treatments for both chlamydia and gonorrhoea show low instances of treatment failure,2,3,7,8,9,10,11 all studies attempted to account for persistent chlamydial or gonocaccal infection due to treatment failure by eliminating data within certain time periods of initial treatment. Most of our reviewed studies looked at high‐risk populations, which may limit the widespread generalisability of our results. Most data were collected at or from records of public STD clinics where only a minority of reported cases of infection are detected in men: 36% of chlamydia and 45% of gonorrhoea.1

Despite these limitations, our review clearly established the considerable proportion of repeat chlamydia and gonorrhoea among men comparable with that among women. Although one of the studies suggests effective reduction of repeat chlamydial and gonococcal infection with EPT,29 a substantial proportion of repeat infection remains. Even with the widespread implementation of EPT, proportions and incidences of both chlamydial and gonococcal reinfection might remain high.

Given the limited resources and the need for focused interventions, targeting previously infected men for retesting might disproportionately reduce the transmission of chlamydia and gonorrhoea, thereby reducing reinfection in women and their subsequent adverse sequelae. Our analysis of the current body of literature established substantial proportions and incidences of repeat chlamydia and gonorrhoea among men that are similar to those among women consistent across studies, suggesting that retesting of all chlamydia‐ and gonorrhoea‐infected men at 3 months after initial treatment should be recommended. We recognise the challenge in implementing successful retesting programmes38,43 and suggest additional research to optimise retesting procedures and establish rates of repeat infection in other populations as a means to further refine retesting guidelines for chlamydial and gonococcal infections among men.

Abbreviations

EPT - expedited partner treatment

NAAT - nucleic acid amplification test

STI - sexually transmitted infection

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance, 2004. Atlanta, GA: Department of Health and Human Services, 2005

- 2.Stamm W E. Chlamydia trachomatis infection of the adult. In: Wasserheit JN, ed. Sexually transmitted diseases. 3rd edn. San Francisco: McGraw‐Hill, 1999407–422.

- 3.Hook E W, Handsfield H H. Gonococcal infections of the adult. In: Wasserheit JN, ed. Sexually transmitted diseases. 3rd edn. San Francisco: McGraw‐Hill, 1999451–466.

- 4.Spiliopoulou A, Lakiotis V, Vittoraki A.et al Chlamydia trachomatis: time for screening? Clin Microbiol Infect 200511687–689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ness R B, Hillier S L, Kip K E.et al Douching, pelvic inflammatory disease, and incident gonococcal and chlamydial genital infection in a cohort of high‐risk women. Am J Epidemiol 2005161186–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simms I, Eastick K, Mallinson H.et al Associations between Mycoplasma genitalium, Chlamydia trachomatis, and pelvic inflammatory disease. Sex Transm Infect 200379154–156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tobin J M, Harindra V, Mani R. Which treatment for genital tract Chlamydia trachomatis infection? Int J STD AIDS 200415737–739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Habib A R, Fernando R. Efficacy of azithromycin 1g single dose in the management of uncomplicated gonorrhoea. Int J STD AIDS 200415240–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stamm W E. Azithromycin in the treatment of uncomplicated genital chlamydial infections. Am J Med 19919119S–22S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martin D H, Mroczkowski T F, Dalu Z A.et al A controlled trial of a single dose of azithromycin for the treatment of chlamydial urethritis and cervicitis. The Azithromycin for Chlamydial Infections Study Group. N Engl J Med 1992327921–925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stamm W E, Guinan M E, Johnson C.et al Effect of treatment regimens for Neisseria gonorrhoeae on simultaneous infection with Chlamydia trachomatis. N Engl J Med 1984310545–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 1993 Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 19934251–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Whittington W L H, Kent C K, Kissinger P.et al Determinants of persistent and recurrent Chlamydia trachomatis infection in young women: results of a multicenter cohort study. Sex Transm Dis 200128117–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fortenberry J D, Brizendine E J, Katz B P.et al Subsequent sexually transmitted infections among adolescent women with genital infection due to Chlamydia trachomatis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, or Trichomonas vaginalis. Sex Transm Dis 19992626–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xu F, Schillinger J A, Markowitz L E.et al Repeat Chlamydia trachomatis infection in women: analysis through a surveillance case registry in Washington State, 1993–1998. Am J Epidemiol 20001521164–1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schillinger J A, Kissinger P, Calvet H.et al Patient‐delivered partner treatment with azithromycin to prevent repeated Chlamydia trachomatis infection among women: a randomized controlled trial. Sex Transm Dis 20033049–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blythe M G, Katz B P, Batteiger B E.et al Recurrent genitourinary chlamydial infections in sexually active female adolescents. J Pediatr 1992121487–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oh M K, Cloud G A, Fleenor M.et al Risk for gonococcal and chlamydia cervicitis in adolescent females: incidence and recurrence in a prospective cohort study. J Adolesc Health 199618270–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bachmann L H, Pigott D, Desmond R.et al Prevalence and factors associated with gonorrhoea and chlamydial infection in at‐risk females presenting to an urban emergency department. Sex Transm Dis 200330335–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Sexually Transmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines 2002. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 20025133–34. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weinstock H, Berman S, Cates W. Sexually transmitted diseases among American youth: incidence and prevalence estimates, 2000. Perspect Sex Reprod Health 2004366–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schillinger J A, Dunne E F, Chapin J B.et al Prevalence of Chlamydia trachomatis infection among men screened in 4 U.S. cities. Sex Transm Dis 20053274–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lewis D A, McDonald A, Thompson G.et al The 374 clinic: an outreach sexual health clinic for young men. Sex Transm Infect 200480480–483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kohl K S, Sternberg M R, Markowitz L E.et al Screening of males for Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae infections at STD clinics in three US cities—Indianapolis, New Orleans, Seattle. Int J STD AIDS 200415822–828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arya R, Mannion P T, Woodcock K.et al Incidence of genital Chlamydia trachomatis infection in the male partners attending an infertility clinic. J Obstet Gynaecol 200525364–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abel G, Brunton C. Young people's use of condoms and their perceived vulnerability to sexually transmitted infections. Aust NZ J Public Health 200529254–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Iser P, Read T H, Tabrizi S.et al Symptoms of non‐gonococcal urethritis in heterosexual men: a case control study. Sex Transm Infect 200581163–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Adimora A A, Schoenbach V J. Social context, sexual networks, and racial disparities in rates of sexually transmitted infections. J Infect Dis 2005191S115–S122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Golden M R, Whittington W L, Handsfield H H.et al Effect of expedited treatment of sex partners on recurrent or persistent gonorrhoea or chlamydial infection. N Engl J Med 2005352676–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Expedited partner therapy in the management of sexually transmitted diseases. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, 2006

- 31.Rothenberg R B. Analysis of routine data describing morbidity from gonorrhoea. Sex Transm Dis 197965–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Judson F N, Wolf F C. Rescreening for gonorrhoea: an evaluation of compliance methods and results. Am J Public Health 1979691178–1180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brooks G F, Darrow W W, Day J A. Repeated gonorrhoea: an analysis of importance and risk factors. J Infect Dis 1978137161–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Noble R C, Kirk N M, Slagel W A.et al Recidivism among patients with gonococcal infection presenting to a venereal disease clinic. Sex Transm Dis 1977439–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hamdad F, Orfila J, Boulanger J C.et al Chlamydia trachomatis urogenital infections in women. Best diagnostic approaches. Gynecol Obstet Fertil 2004321064–1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Olshen E, Shrier L A. Diagnostic tests for chlamydial and gonorrhoeal infections. Semin Pediatr Infect Dis 200516192–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kellogg N D, Baillargeon J, Lukefahr J L.et al Comparison of nucleic acid amplification tests and culture techniques in the detection of Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis in victims of suspected child sexual abuse. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 200417331–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Malotte C K, Ledsky R, Hogben M.et al Comparison of methods to increase repeat testing in persons treated for gonorrhoea and/or chlamydia at public sexually transmitted disease clinics. Sex Transm Dis 200431637–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kissinger P, Mohammed H, Richardson‐Alston G.et al Patient‐delivered partner treatment for male urethritis: a randomized, controlled trial. Clin Infect Dis 200541623–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McKee K T, Jenkins P R, Garner R.et al Features of urethritis in cohort of male soldiers. Clin Infect Dis 200030736–741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Orr D P, Johnston K, Brizendine E.et al Subsequent sexually transmitted infections in urban adolescents and young adults. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2001133947–953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wagstaff D A, Delamater J D, Havens K K. Subsequent infection among adolescent African‐American males attending a sexually transmitted disease clinic. J Adolesc Health 199925217–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Golden M R, Clark A, Malinksi C.et al Linking mailed rescreening for gonorrhoea and chlamydial infection to partner notification. Poster at International Society for Sexually Transmitted Disease Research, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, July 2005

- 44.Dunne E F, Chapin J B, Rietmeijer C.et al Repeat infection with Chlamydia trachomatis: rates and predictors among males. Presented at the National STD Prevention Conference, Philadelphia, PA, March 2004

- 45.Peterman T A, Tian L H, Metcalf C A.et al High incidence of new sexually transmitted infections in the year following a sexually transmitted infection: a case for rescreening. Ann Intern Med 2006145564–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bernstein K T, Zenilman J, Olthoff G.et al gonorrhoea reinfection among sexually transmitted disease clinic attendees in Baltimore, Maryland. Sex Transm Dis 20063380–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ellen J M, Gaydos C, Chung S E.et al Sex partner selection, social networks, and repeat sexually transmitted infections in young men: a preliminary report. Sex Transm Dis 20063318–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sparks R, Helmers J R, Handsfield H H.et al Rescreening for gonorrhoea and chlamydia infection through the mail: a randomized trial. Sex Transm Dis 200431113–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kjaer H O, Dimcevski G, Hoff G.et al Recurrence of urogenital Chlamydia trachomatis infection evaluated by mailed samples obtained at home: 24 weeks' prospective follow up study. Sex Transm Infect 200076169–172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gunn R A, Maroufi A, Fox K K.et al Surveillance for repeat gonorrhoea infection, San Diego, California, 1995–2001: establishing definitions and methods. Sex Transm Dis 200431373–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lee V F, Tobin J M, Harindra V. Re‐infection of Chlamydia trachomatis in patients presenting to the genitourinary medicine clinic in Portsmouth: the chlamydia screening pilot study—three years on. Int J STD AIDS 200415744–746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mehta S D, Erbelding E J, Zenilman J M.et al Gonorrhoea reinfection in heterosexual STD clinic attendees: longitudinal analysis of risks for first reinfection. Sex Transm Infect 200379124–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rietmeijer C A, van Bemmelen R, Judson F N.et al Incidence and repeat infection rates of Chlamydia trachomatis among male and female patients in an STD clinic: implications for screening and rescreening. Sex Transm Dis 20022965–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gunn R A, Fitzgerald S, Aral S O. Sexually transmitted disease clinic clients at risk for subsequent gonorrhoea and chlamydia infections: possible ‘core' transmitters. Sex Transm Dis 200027343–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Thomas J C, Weiner D H, Schoenback V J.et al Frequent re‐infection in a community with hyperendemic gonorrhoea and chlamydia: appropriate clinical actions. Int J STD AIDS 200011461–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kent C K, Chaw J K, Kohn R P.et al Studies relying on passive retrospective cohorts developed from health services data provide biased estimates of incidence of sexually transmitted infections. Sex Transm Dis 200431596–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]