Abstract

Objective

To give an overview of the latest latest trends in diagnoses made and services provided by genitourinary medicine (GUM) clinics in the UK.

Methods

Aggregate data collected from the KC60 statistical returns for GUM clinics in England, Wales and Northern Ireland and disaggregate data collected using the STI Surveillance System for GUM Clinics in Scotland. These data were collated and numbers of diagnoses were adjusted for missing clinic data.

Results & Conclusion

Overall, numbers of new diagnoses of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) continued to rise in 2006. However, there was some evidence of improvement, with new diagnoses of gonorrhoea falling for the fourth successive year. Chlamydia continued to be the most common STI diagnosed in GUM clinics, and the sharp rise in new diagnoses over the last 10 years was most likely associated with an increase in testing volume and accuracy. The highest rates of STI diagnoses continued, in the main, to be among 16–24‐year‐olds, and there were some notable rises among this age group also: new diagnoses of genital herpes in teenage women rose by 16% in 2006. Improving the sexual health of men who have sex with men (MSM) must remain a priority, as the increase in numbers of new STI diagnoses among MSM over the past 10 years continued unabated into 2006. However, despite facing the challenge of reducing patient waiting times, there has been a considerable rise in sexual health screens and HIV tests being provided by GUM services, and this could, if sustained, result in significant improvements in sexual health in the coming years.

On 20 July 2007, in London, the Health Protection Agency held a press conference on the latest data from UK genitourinary medicine (GUM) clinics in London. Although new diagnoses of STIs made by GUM clinics have in general continued to rise, rates vary substantially between conditions: some increased, whereas others decreased. Details of methods of data collection and analysis are available elsewhere.1,2,3 For clinics where data for all 4 quarters had not been received, reports were adjusted to account for missing data. A list of the conditions diagnosed and services provided at GUM clinics is provided in table 1.

Table 1 Conditions diagnosed and services provided at GUM clinics.

| New STI diagnoses |

| Chlamydial infection (uncomplicated and complicated) |

| Gonorrhoea (uncomplicated and complicated) |

| Infectious syphilis |

| Genital herpes simplex (first attack) |

| Genital warts (first attack) |

| New HIV diagnosis |

| Non‐specific genital infection (uncomplicated and complicated) |

| Chancroid/lymphogranuloma venerum (LGV)/Donovanosis |

| Molluscum contagiosum |

| Trichomoniasis |

| Scabies |

| Pediculus pubis |

| Other STI diagnoses |

| Early latent, congenital and other acquired syphilis |

| Recurrent genital herpes simplex |

| Recurrent and re‐registered genital warts |

| Subsequent HIV presentations (including AIDS) |

| Ophthalmia neonatorum (chamydial or gonococcal) |

| Epidemiological treatment of suspected STIs (syphilis, chlamydia, gonorrhoea, non‐specific genital infection) |

| Other diagnoses made at GUM clinics |

| Viral hepatitis B and C |

| Vaginosis and balanitis (including epidemiological treatment) |

| Anogenital candidiasis (including epidemiological treatment) |

| Urinary‐tract infection |

| Cervical abnormalities |

| Other conditions requiring treatment at a GUM clinic |

| Services provided |

| HIV antibody test |

| Sexual‐health screen |

| Hepatitis B vaccination |

| Contraception (excluding condom provision) |

| Other episode not requiring treatment |

Diagnoses and services provided

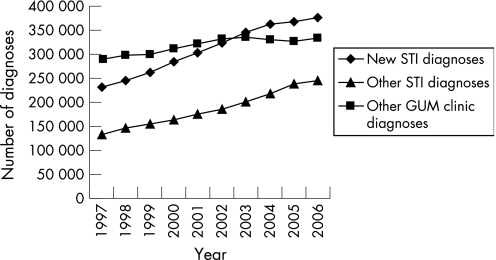

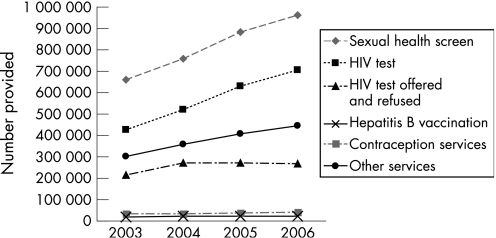

Between 2005 and 2006, new STI diagnoses rose by 2% overall from 368 341 to 376 508; other STI diagnoses rose by 3% from 238 204 to 244 804; and other diagnoses, which are not necessarily sexually acquired, increased by 2% from 326 910 to 334 314. Taking a more long‐term view, the 10 years from 1997 to 2006 saw a rise in new STI diagnoses of 63% (from 231 185 to 376 508), other STI diagnoses increased by 84% (from 133 371 to 244 804), whereas other diagnoses rose by just 16% (from 289 277 to 334 314) (fig 1). Total services provided have been measured since 2003 when new activity codes were introduced. Between 2005 and 2006, total services provided within the clinics, including sexual health screens and HIV testing, rose by 6% from 1 698 676 to 1 803 739. The number of HIV tests undertaken rose by 12% from 628 810 to 705 502, and the number of sexual health screens rose by 9% from 882 593 to 960 868 (fig 2).4

Figure 1 Diagnoses made in GUM clinics in the UK, 1997 to 2006.

Figure 2 Services provided in GUM clinics in the UK, 2003 to 2006.

Selected STIs

Between 2005 and 2006, diagnoses of gonorrhoea fell by 1%, as did diagnoses of syphilis, whereas diagnoses of chlamydia, genital herpes and genital warts rose by 4%, 9% and 3%, respectively. Detailed information by sex and age group and longer‐term historical trends are posted on the HPA website.3 2006 is the fourth successive year for which numbers of diagnoses of gonorrhoea have fallen. Chlamydia, with 113 585 diagnoses in 2006, continues to be the most common condition diagnosed in GUM clinics. The difference between the 2006 figure and the 42 668 diagnoses made in 1997 is mainly accounted for by an increase in volume and accuracy of testing.

Risk groups

Although disaggregate (patient based) information is collected for Scotland, only aggregate data are currently available for the other countries of the UK. Consequently, aggregate data have been used here. The aggregate datasets collect little information on the determinants of incidence: information on age and male sexual orientation is only collected for a limited number of conditions. However, these data still highlight groups at increased risk of sexually transmitted infection within the UK. In 16–19‐year‐old women, the increases in genital herpes and genital warts between 2005 and 2006 were 16% and 5%, respectively. Age‐specific rates in most of the major STIs were also highest in 16–19‐year‐old women and 20–24‐year‐old men. The exceptions were slightly higher rates for herpes and syphilis in 20–24‐year‐old women, and highest rates of syphilis were seen among men aged 35–44 years old. In MSM, numbers have risen consistently in all the major diagnoses over the last 10 years; syphilis from 19 to 1417: gonorrhoea from 1954 to 4524: chlamydia from 387 to 3239, genital herpes (first attack) from 337 to 604, and genital warts (first attack) from 1639 to 2691.

Conclusions

Because the collection of data from GUM clinics has been statutory for many decades, they give a robust overview of historic trends in STI epidemiology in the UK over a substantial period of time. The overall increase of 2% in STI diagnoses made in GUM clinics together with the increase in workload, particularly the 6% increase in services provided, has put further pressure on an already‐stretched clinical service. In England, the fact that this has been handled within the context of decreasing waiting times (72% of patients were seen within 48 h of contacting the service according to the May 2007 audit5) endorses the way in which GUM services are handling this challenge. However, the sexual health in MSM and young people has not improved since the late 1990s. Investigation into the re‐emergence of syphilis has revealed a complex association between syphilis and HIV, and continued high‐risk sexual behaviour,6 a pattern that has also been seen in the epidemics of gonorrhoea and lymphogranuloma venereum.7

The National Chlamydial Screening Programme (NCSP) has shown that there is a substantial reservoir of genital chlamydial infection in young people attending healthcare and non‐healthcare settings outside GUM services. Sexual‐health services are being extended to settings outside GUM, including pharmacies, to increase patient choice and normalise testing. Diagnoses made in general practice and through the NCSP are not included in the GUM dataset. Improving surveillance of STIs in non‐GUM settings is a priority.

A detailed discussion of recent trends in epidemiology of STIs and HIV will be presented in the 2007 HIV and STI Annual Report to be published by the Health Protection Agency in late November (http://www.hpa.org.uk).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the staff of GUM clinics for providing information used in this article, together with Anne Leigh‐Brown (Information Services [ISD], NHS National Services Scotland), Daniel Rh. Thomas (National Public Health Service for Wales, Communicable Disease Surveillance Centre), Neil Irvine (Communicable Disease Surveillance Centre, Northern Ireland) and Barry Evans (Centre for Infections, England).

Abbreviations

GUM - genitourinary medicine

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Brown A E, Sadler K E, Tomkins S E.et al Recent trends in HIV and other STIs in the United Kingdom: data to the end of 2002. Sex Transm Inf 200480159–166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.The UK Collaborative Group for HIV and STI Surveillance A complex picture. HIV and other sexually transmitted infections in the United Kingdom. London: Health Protection Agency, Centre for Infections, 2006

- 3.Health Protection Agency 2006 STI data. http://www.hpa.org.uk/infections/topics_az/hiv_and_sti/epidemiology/datatables2006.htm#data (accessed 14 Aug 2007)

- 4.Health Protection Agency Sexually transmitted infection diagnoses and services provided in genitourinary medicine clinics in the UK in 2006. http://www.hpa.org.uk/hpr/archives/2007/news2007/news2907.htm (accessed 14 Aug 2007)

- 5.Health Protection Agency GUM clinics waiting time May 2007 audit. http://www.hpa.org.uk/infections/topics_az/hiv_and_sti/epidemiology/pdf/gum_May07_summary.pdf (accessed 14 Aug 2007)

- 6.Simms I, Fenton K A, Ashton M.et al The re‐emergence of syphilis in the UK: the new epidemic phases. Sex Transm Dis 200532220–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ward H, Martin I, Macdonald N, Alexander S, Simms I, Fenton K A, French P, Dean G, Ison C for the UK LGV Incident Group Lymphogranuloma venereum in the United Kingdom. Clin Infect Dis 20074426–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]