Abstract

A living cell deforms or flows in response to mechanical stresses. A recent report shows that dynamic mechanics of living cells depends on the timescale of mechanical loading, in contrast to the prevailing view of some authors that cell rheology is timescale-free. Yet the molecular basis that governs this timescale-dependent behavior is elusive. Using molecular dynamics simulations of protein-protein noncovalent interactions, we show that multipower laws originate from a nonequilibrium-to-equilibrium transition: when the loading rate is faster than the transition rate, the power-law exponent α1 is weak; when the loading rate is slower than the transition rate, the exponent α2 is strong. The model predictions are confirmed in both embryonic stem cells and differentiated cells. Embryonic stem cells are less stiff, more fluidlike, and exhibit greater α1 than their differentiated counterparts. By introducing a near-equilibrium frequency feq, we show that all data collapse into two power laws separated by f/feq, which is unity. These findings suggest that the timescale-dependent rheology in living cells originates from the nonequilibrium-to-equilibrium transition of the dynamic response of distinct, force-driven molecular processes.

INTRODUCTION

All living cells deform or flow in response to externally applied stresses. The underlying molecular mechanisms for these cellular responses are far from clear. During the last several years a soft glass rheology (SGR) model (1) has been developed to explain the weak power-law dependence of cell stiffness on loading frequency (2–4). These soft, glassy materials are thought to be in the nonequilibrium phase state and to share a common feature of “slow localized inelastic rearrangements”, although the exact molecular and structural mechanisms for SGR have not been identified (4). The SGR model has generated interest in the field of cell rheology, and the weak power-law behavior has been confirmed in several cell types using different probing technologies (5,6). Since there are thousands of different proteins and many more protein-protein interactions in a cell, it seems reasonable that there should be a wide distribution of time constants among protein-protein interactions, consistent with the statement that the “power law behavior implies that relaxation processes are not tied to any particular internal time scale” (2). However, it is well established that important characteristic time constants appear to be always on the order of 1–10 s at different length scales, ranging from protein conformational changes and/or unfolding (7,8), specific protein-protein interactions, periodic lamellipodial contractions (9), optimal stress propagation in the cytoskeleton (10), and stress-induced protein translocation across the cytoplasm (11) to essential mechanical functions at the tissue/organ level, such as heartbeat and breathing. These time constants are likely to be crucial in setting other, longer (minutes to hours) timescale-dependent cell functions such as cell spreading, migration, invasion, gene expression, protein synthesis, proliferation, and apoptosis. It is important to note that extending mechanical loading frequencies to these physiologically relevant, longer timescales (minutes) revealed recently that there exist two distinct regimes in living cells that are characterized by different power laws (12). This demonstrates that cell rheology is timescale-dependent (12). This experimental observation raises some fundamental questions, namely, 1), what is the molecular mechanism that governs this timescale-dependent rheological behavior? and 2), what dictates the transition from one power-law regime to another?

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture

Human airway smooth muscle (ASM) cells were isolated as described previously (13) and cultured as described (14). Human ASM cells were serum-deprived and supplemented with 5.7 μg/ml insulin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) and 5 μg/ml human transferrin (Sigma) 24 h before the experiments. ATP was depleted with serum and glucose-free Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium with 0.05% sodium azide (Alfa Aesar, Ward Hill, MA) and 50 mM 2-D-deoxyglucose for 30 min before data collection (6). We diluted 2% glutaraldehyde (Glut) from 25% stock solution and added it to the medium for 60 min after the beads had been bound for 15 min. Similar results were found for 1% Glut for 5 min, although the stiffness values were lower and α1 was higher (0.09) when compared with beads treated with 2% Glut for 60 min; α2 was 0.69, similar to baseline ASM cells. Undifferentiated mouse embryonic stem (mES) cells (W4, 129/SvEv) (15) were maintained in the standard culture condition in the presence of leukaemia inhibitory factor (LIF). The details of the mES cell culture can be found elsewhere (16–18). In short, to maintain mES cells as undifferentiated, we used the complete ES medium consisting of high-glucose Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium, 15% ES qualified fetal bovine serum, 2 mM glutamine, 0.1 mM modified Eagle's medium nonessential amino acid solution (all from Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), 0.1 mM b-mercaptoethanol, 50 mg/ml penicillin-streptomycin (Sigma), 1 mM sodium pyruvate (Invitrogen), and 1000 U/ml ESGRO LIF (Chemicon, Temecula, CA). Mouse ES cells at passage 13 were thawed onto a feeder layer of mitotically inactivated primary murine embryonic fibroblasts (mEFs) (19). Before assays, mES cells were passaged onto plates coated with 0.1% gelatin several times every 2 days to remove feeders. mEF- and mES-differentiated (ESD) cells were cultured with the complete medium without LIF.

Differentiation assay

For the differentiation assay, trypsinized mES cells at passage 17–18 were plated on gelatin-coated dishes at a density of 100 cells/cm2. Next day, the mES cells were fed with the medium without LIF (LIF−) and with 1 μM retinoic acid (all-trans, Sigma) (LIF−/RA+). The mES cells in these conditions were fed with fresh medium every day for 4–5 days before experiment. In the LIF−/RA+ culture condition, mES cells became differentiated (20).

Measurement of dynamic stiffness

Microrheology of cells was carried out with magnetic twisting cytometry (MTC) (2–4,10,21,22). Ferromagnetic microbeads (4.5 μm in diameter) coated with a synthetic peptide containing the Arg-Gly-Asp (RGD) sequence were used to probe the dynamic modulus of the cells. The beads were incubated for 10–15 min to adhere to the apical surface of the cells so that they would become tightly bound to the F-actin cytoskeleton through transmembrane integrin receptors. Beads that were not on the cell surface and that were loosely bound to the cell surface were excluded for data analyses. In addition, bead displacements that did not conform to the input sinusoidal waveform and frequency were excluded for data analyses, minimizing potential contributions from spontaneous bead movements or microscope-stage shifts (2–4). Bead displacements of <5 nm (the detection resolution) were also excluded. During the sinusoidal oscillatory frequency sweep, two different loading protocols were used to keep the probing time ∼10 min. In the first, the frequency sweep points were 0.01, 0.1, 1, 10, 100, and 1000 Hz; in the second, they were 0.002, 0.04, and 0.2, all at a peak amplitude of 8.75 Pa (25 G). Thus, this work does not address the question of whether the stress-strain relationship is linear or nonlinear, because although this is quite interesting, the mechanisms for living cells are not fully understood. Published work also shows that the harmonic distortion index (which characterizes the extent to which the input-output loop deviates from the linear elliptic shape) does not become suddenly greater at low frequencies, indicating that α2 is not due to the nonlinear behavior of living cells (12). We measured the complex stiffness as a function of frequency by applying an oscillatory magnetic field and measuring the resultant oscillatory bead motions using the relation G* = T/d, where T is oscillatory specific torque resulting from the oscillatory magnetic field of different frequency and d is the induced horizontal displacement of the beads measured using a charge-coupled device camera attached to an inverted optical microscope. For each bead, we then calculated the elastic stiffness, G′ (the real part of G*), and the dissipative stiffness, G″ (the imaginary part of G*). The measured stiffnesses have the units of torque per unit bead volume per unit bead displacement (Pa/nm). If one assumes a bead-cell contact area (generally ∼10% of the bead surface area) and uses a homogeneous elastic solid model and finite-element analyses to convert stiffness (Pa/nm) to modulus (Pa) (23), then 1 Pa/nm stiffness is equivalent to 6.8 kPa modulus, but the power-law slopes do not change. F-tests were used for statistical analysis.

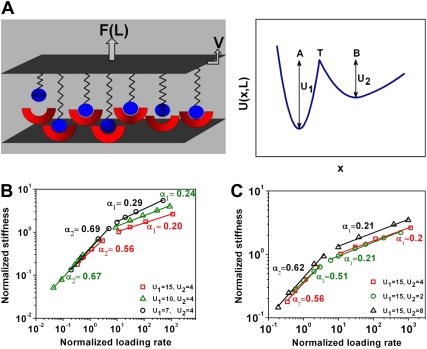

Molecular model description

Protein-protein interactions were modeled as two surfaces bearing 1000 molecular noncovalent bonds, as shown in Fig. 1 A. This model has previously been described in detail (24). In brief, the top surface is displaced at a constant loading rate, V, such that the separation distance, L, is V × t at time t. The total potential energy is U(x, L) = U0(x) + Us(x, L) where U0(x) is the intrinsic energy for noncovalent bonds and Us(x, L) is the harmonic pulling force, and these terms are defined as

|

and

|

We used a statistical mechanics framework to compute the bond population and the total force exerted by the bonds under thermodynamic equilibrium, near-equilibrium, and far-from-equilibrium (nonequilibrium) conditions as described in Li and Leckband (24). The coordinate x measures the distance between a pair of molecules along the pulling direction (Fig. 1).  equals the difference between U1 and U2 (see Results section for definitions of U1 and U2). In this process, the association and dissociation rate constants kon and koff are determined (24). We define Vc as the critical separation rate. Li and Leckband defined Vc as the distance to bond rupture divided by the intrinsic relaxation time of the unperturbed bond (24). For each molecule, a critical separation rate, Vc, was calculated based on their intrinsic relaxation times (24). Total rupture force increases with the number of parallel bonds. Normalized rupture force can be plotted as a function of the normalized loading rate, V/Vc. A basic assumption in this model is that the applied force or applied loading is large enough to reach the rupture force of the bonds. This assumption is reasonable given the fact that all noncovalent bonds between proteins range from a few kT to a dozen kT; external mechanical perturbations that lead to a force of a few piconewtons on a single bond will rupture the bond. Since the dynamic stiffness is a measure of the bond number and the combined-bond elasticity of molecular interactions, it is proportional to the normalized rupture force, and therefore, the points in Fig. 1, B and C, were plotted with normalized stiffness as a function of normalized loading rate. The separation distances ranged from 3 to 18 nm, within the length scales of proteins. The computation software was written in MATLAB (The MathWorks, Natick, MA), adapted and modified from Li (25).

equals the difference between U1 and U2 (see Results section for definitions of U1 and U2). In this process, the association and dissociation rate constants kon and koff are determined (24). We define Vc as the critical separation rate. Li and Leckband defined Vc as the distance to bond rupture divided by the intrinsic relaxation time of the unperturbed bond (24). For each molecule, a critical separation rate, Vc, was calculated based on their intrinsic relaxation times (24). Total rupture force increases with the number of parallel bonds. Normalized rupture force can be plotted as a function of the normalized loading rate, V/Vc. A basic assumption in this model is that the applied force or applied loading is large enough to reach the rupture force of the bonds. This assumption is reasonable given the fact that all noncovalent bonds between proteins range from a few kT to a dozen kT; external mechanical perturbations that lead to a force of a few piconewtons on a single bond will rupture the bond. Since the dynamic stiffness is a measure of the bond number and the combined-bond elasticity of molecular interactions, it is proportional to the normalized rupture force, and therefore, the points in Fig. 1, B and C, were plotted with normalized stiffness as a function of normalized loading rate. The separation distances ranged from 3 to 18 nm, within the length scales of proteins. The computation software was written in MATLAB (The MathWorks, Natick, MA), adapted and modified from Li (25).

FIGURE 1.

Molecular dynamics model of noncovalent protein-protein bonds exhibits two power-law exponents. This model describes the effect of forces and loading rates in protein-protein interactions with 1000 parallel noncovalent bonds (2–15 kT). (A) Shown at left is a schematic of the model, in which the top surface bears molecules with identical elastic linkers and the bottom surface bears the “receptor” molecules. The top surface is displaced at a rate V with force F. The total applied force, F, is measured as a function of the separation distance, L, between the two surfaces bearing the molecules. At right, a typical total potential energy U(x) is plotted as a function of reaction coordinate x with bound (A), transition (T), and free (B) states. The coordinate x measures the distance between a pair of molecules in the pulling direction. The energy well barrier depths in states A and B are defined as U1 and U2, respectively (adapted from Auerbach et al. (15)). (B) Normalized stiffness exhibits two power laws as a function of the normalized loading rate, V/Vc,. When U2 was kept constant at 4 kT, the power-law exponent α1 increased with decreasing U1. The exponent α2 also increased as U1 was decreased. (C) When U1 was kept constant, α1 remained unchanged, whereas α2 increased as U2 was doubled and decreased as U2 was halved from 4 kT. Decreasing the noncovalent bond number from 1000 to 100 or to 10 did not alter α1 but increased α2 (Fig. S4, Data S1); this is expected, since fewer bonds means less probability for the detached bonds to reattach and thus the viscous drag plays a greater role in setting the slope of the power law at different low loading frequencies (the slope is 1 for water). Altering the geometric contact parameters from two parallel plates to a curved surface (e.g., a bead) and a flat surface changed power laws very little (25), consistent with living-cell data showing that similar power laws are observed in loading modes with either beads (6,12) or parallel plates (47), suggesting that this model is applicable to different loading modes.

It is important to emphasize that the creep experiments are fundamentally different from measurements done at constant loading rates in this model. In the creep experiments, a step force is applied and one follows the system as it relaxes to a new “equilibrium” state. In the loading rate measurements, the force steadily increases up to the point of cohesive failure. In this case, the density of kinetically trapped states at the rupture distance (approximately the bond length) defines the rupture force. There is “molecular relaxation” throughout the process as bonds are breaking and reforming. The relaxation time, in this case, comes into play because the time to reach the maximum bond extension relative to the intrinsic molecular relaxation rate determines the population of kinetically trapped states (and hence the rupture force) at failure.

RESULTS

Two power-law exponents in cells arise from transition between equilibrium and nonequilibrium

We extended a well-established approach of molecular dynamics simulation (MDS) (26), since it is difficult to address these questions experimentally at the multimolecular level using a wide range of loading frequencies (27). Following the model proposed in a recent report (24) and adapting it to examine dynamic rheology of a living cell, we analyzed the dynamic strengths of multiple parallel noncovalent bonds with different energy barrier magnitudes ranging from 2 to 15 kT. These values are well below the ATP hydrolysis energy (∼25 kT) (28) and thus cover all energy barrier levels of noncovalent bonds between specific proteins in protein-protein interactions. The model assumes that the protein-protein bond transits from the bound state, A, to the unbound state, B (Fig. 1 A). Here, U1 is the energy difference between the ground state and the transition state (U1→U2), and U2 is the energy difference between the energy minimum and the transition state (U2→U1).The transitions between U1 and U2 are characterized by corresponding association and dissociation rate constants kon and koff, which are determined by U1 or U2. Vc is the critical loading rate, which defines the transition between equilibrium and nonequilibrium loading conditions (24), When the loading rate, V, was much higher than Vc for the particular protein bond, the normalized dynamic strength or stiffness (equivalent to the normalized dynamic force) exhibited weak power-law behavior (Fig. 1 B). When the power law slope is much less than 0.5, it is called “weak”. Otherwise, it is “strong”. The power-law exponent α1 increased from 0.20 to 0.29 when U1 decreased from 15 kT to 7 kT, demonstrating that dissipative energy increases when U1 decreases. Since the dissociation rate constant, koff, depends exponentially on U1, this result also shows that α1 inversely depends on the magnitude of koff. When the loading rate was much lower than Vc, a different and strong power-law slope, α2, emerged (Fig. 1 B). The exponent α2 increased from 0.56 to 0.69 when U1 decreased from 15 kT to 7 kT. This suggests that like α1, α2 inversely depends on the magnitude of koff. In contrast, the exponent α1 varied little when U2 decreased from 4 kT to 2 kT or increased from 4 kT to 8 kT, suggesting that α1 does not depend on the association rate constant kon, which depends exponentially on U2 (Fig. 1 C). It is interesting to note that α2 increased from 0.51 to 0.62 when U2 increased from 2 kT to 8 kT. In addition, the magnitudes of the dynamic stiffness increased when U2 increased (Fig. 1 C). All of these results together demonstrate that the two power-law exponents are separated by a transition region of “near equilibrium” (V/Vc ∼ 1), which separates the equilibrium loading region (V/Vc ≪ 1) from the nonequilibrium region (V/Vc ≫ 1).

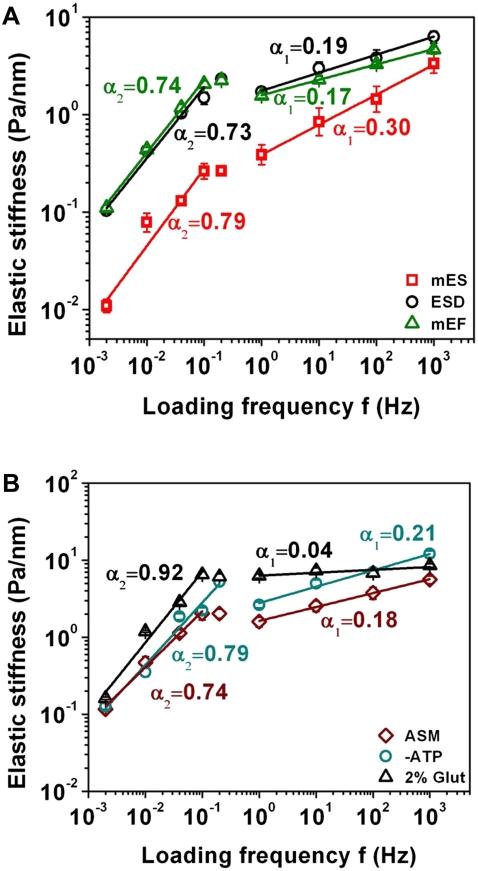

Embryonic stem cells are intrinsically different from differentiated cells

To test the validity of our MDS model, we performed a loading frequency scan while quantifying the dynamic elastic stiffness G′ in living cells. mES cells have been the premier model system used to understand mechanisms of cell fate decision. However, very little is known about the mechanical behavior of these cells. We set out to determine the dynamics of mES cell mechanics. It is of interest that mES cells exhibited a higher value of α1 (0.3) than did the cells that differentiated from these ES cells (ESD cells; α1 = 0.19). In contrast, the α2 of mES cells (0.79) was only slightly higher than that of the differentiated cells (α2 = 0.74) (Fig. 2 A). Other differentiated cells, such as mEFs (Fig. 2 A) or ASM cells (Fig. 2 B), had power-law exponents similar to those of the ESD cells for both α1 and α2. Moreover, mES cells were much softer than the differentiated cells, especially at lower loading frequencies (Fig. 2 A), consistent with our observation that mES cells had fewer F-actins and stress fibers. It is of interest that at loading frequencies of 1–100 Hz, the ratios of the dissipative stiffness, G″, to the elastic stiffness G′ (G″/G′) for mES cells were much greater than those for ESD cells (Supplementary Material, Fig. S1, Data S1), suggesting that mES cells are not only softer but also more fluidlike than ESD cells. Numerous published reports show that MTC technology is a reliable method for probing the rheological properties of the cytoplasm (2–4,6,10) and not just for probing surface ligand-receptor interactions. Therefore, these differences also could not be explained by the differences in bead-cell contact areas or in ligand-receptor interactions. mES cells generally come into contact with each other to create cell-cell adhesions (Fig. S2, A and B. Data S1); we wondered whether these differences in power laws are due to different cell adhesions. However, when we compared subconfluent cells with confluent cells, which have numerous cell-cell adhesions (Fig. S2, E and F, Data S1), the power-law slopes were similar, although the magnitudes of stiffness were slightly higher in confluent cells (Fig. S3, Data S1), suggesting that the state of cell adhesion plays a very minor role in determining the power laws. All these results suggest that the differences observed in α1 reflect the intrinsic differences in the cytoplasmic rheological properties between embryonic stem cells and differentiated cells.

FIGURE 2.

Dynamic elastic stiffness (G′) exhibits two power laws in embryonic stem cells and differentiated cells. G′ = geometric mean ± geometric standard error. The applied stress was 8.75 Pa (25 G). (A) ES cells are softer and more fluid than differentiated cells. Mouse embryonic stem (mES) cells (the total number of beads is 242 for two loading protocols) exhibit higher α1 and α2 than the cells that differentiated from these ES cells (ESD; n = 290 beads; p < 2.5 × 10−7 for α1 and p < 0.003 for α2) and murine embryonic fibroblasts (mEF; n = 404 beads; p < 2.7 × 10−7 for α1; p < 7.3 × 10−4 for α2). Comparing α1 to α2 within the same cell type, p < 0.003 for mES cells; p < 4.5 × 10−6 for ESD cells; p < 5.3 × 10−7 for mEF cells. (B) Power laws are intrinsic material properties of cells. ASM, intact human ASM cells at baseline conditions (n = 238 beads); −ATP, depletion of ATP for 30 min (n = 118 beads); 2%Glut, ASM cells treated with 2% Glut for 60 min (n = 174 beads). Note that 2%Glut treatment almost completely abolished the exponent α1 and increased the exponent α2. Comparing 2% Glut with ASM, p < 1 × 10−8 for α1 and p < 8.9 × 10−6 for α2; comparing −ATP with ASM, p < 7.3 × 10−9 for α1 and p < 4.1 × 10−4 for α2.

The origins of power-law exponents α1 and α2

To further test whether these power-law exponents depended on metabolic energy, ATP was depleted for 30 min (6). Interestingly, both α1 and α2 changed only slightly in ASM cells when ATP was depleted (Fig. 2 B), consistent with published ATP depletion data in living cells (6). These results suggest that two power-law exponents reflect intrinsic ATP-independent material properties of the cells. Because of the numerous similarities between MDS data and the live-cell experimental data, we wondered whether the power-law exponents α1 and α2 arise from the association and dissociation processes of cellular proteins. An effective way to test this idea is to cross-link the proteins in the cell. Cross-linking proteins in smooth muscle cells with 2% Glut almost completely abolished α1 (it was dramatically attenuated to 0.04) and increased α2 to 0.92 (Fig. 2 B). A theoretical prediction from a pure elastic solid is that α1 is zero. These results indicate that these fixed cells behaved almost like an elastic solid at loading frequencies of 0.1–1000 Hz. At frequencies of 0.002–0.1 Hz, α2 is 0.92, possibly due to the fact that when these bonds were broken because of extended periods of loading, they could not re-form because all the molecules were covalently cross-linked by Glut. Therefore, the resistance to loading originates mostly from the viscous drag of the liquid surrounding the proteins, whose slope in theory should be 1. Together with the ATP depletion data, these findings suggest that α2 does not originate from active cellular remodeling processes, but rather results from noncovalent protein-protein bond rupture during the near-equilibrium loading. The exponent α1 appears to originate from the rupture of noncovalent protein-protein bonds in the nonequilibrium loading region.

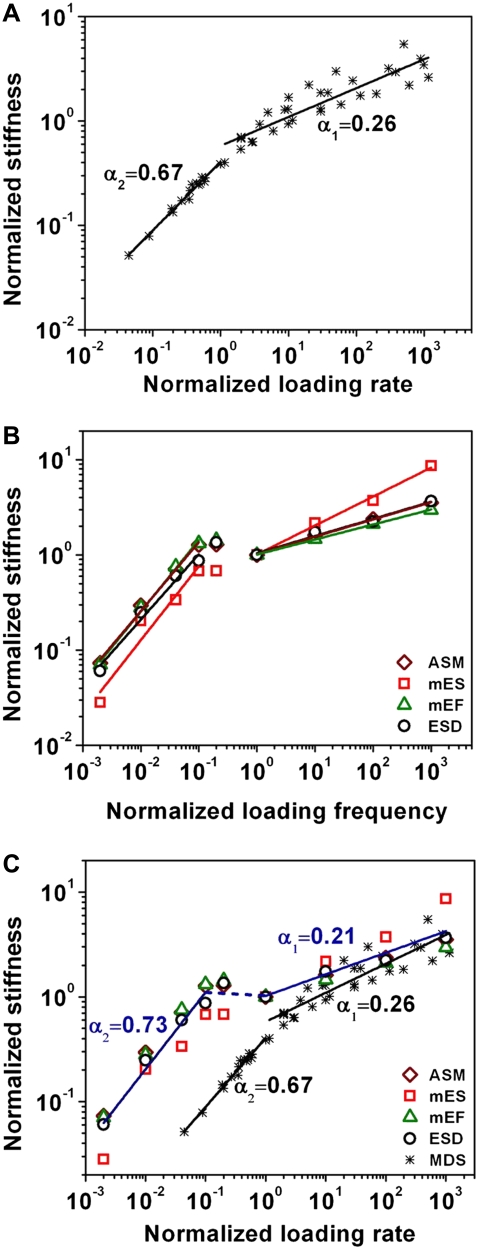

Experimental cell data and simulation data collapse into a master plot

To further explore the mechanisms underlying the cell data, we plotted all simulated data for all bonds with different values of U1 and U2 on to one graph (Fig. 3 A). The power-law exponents α1 and α2 of the normalized dynamic stiffness versus the normalized loading rate are 0.26 and 0.67, respectively (Fig. 3 A). Defining the frequency at 1 Hz as the effective near-equilibrium loading frequency feq of live cells, the dynamic elastic stiffness was normalized by the elastic stiffness at feq, and loading frequency was normalized by feq (Fig. 3 B). The thus normalized experimental data from the different types of living cells collapse onto a curve with two power-law exponents separated by a transition region (Fig. 3 B). By superimposing Fig. 3 A onto Fig. 3 B, it is amazing that these data qualitatively and quantitatively match well (Fig. 3 C), with the exception that there is a near-plateau region in the live-cell data. These findings strongly suggest that the molecular origin of the two power laws observed with live cells originates from differences in the nonequilibrium versus near-equilibrium dynamic response of noncovalent protein-protein bonds to time-varying forces.

FIGURE 3.

Universal multipower laws originate from the nonequilibrium-to-equilibrium transition. (A) All data points for five types of molecules of different energy well depths in Fig. 1, B and C, are included. Two power-law exponents, α1 and α2, emerged. (B) Defining the frequency at 1 Hz as the near-equilibrium frequency, feq, and the elastic stiffness at feq as G′eq, all experimental data of intact living cells in Fig. 2 are normalized and plotted as G′/G′eq versus f/feq. (C) Experimental and modeling data are collapsed into a single curve with two power-law exponents, α1 and α2. Note that normalized loading rate and normalized loading frequency are both dimensionless and equivalent. The dashed line that connects the two slopes represents the transition region in living cells. mES, ESD, mEF, and ASM represent different cell types described in Fig. 2; MDS, data from the molecular dynamics simulation model.

DISCUSSION

In the MDS model, the weak power laws originate from the fact that as the loading rate increases, the number of kinetically trapped bonds in state A (the bound state) increases, leading to greater rupture force and thus greater stiffness (24). As the loading rate is greater than the critical loading rate, Vc (or the near-equilibrium loading rate), the rupture force does not depend on kon/koff or keq; rather, the rupture force decreases linearly only with log koff, which is proportional to U1 (the activation energy for unbinding from bound state A) through the Arrhenius equation (24). The system is in the thermodynamic far-from-equilibrium regime (24) or the nonequilibrium regime. Our model data are consistent with published data that suggest that the cytoskeleton in living cells is not in the thermodynamic equilibrium (3). This fundamental basis of the model appears to be able to explain the weak power-law α1 observed in living cells.

In the SGR model, the molecular mechanisms underlying the weak power-law exponent α1 are currently not known, although several possibilities could explain the “slow inelastic rearrangement” behavior. Examples are polymer entanglements, structural rearrangements from crowding, caging, and jamming, slow relaxation of protein structures, and the slow turnover of covalent or noncovalent bonds (4). Thus, seven different explanations or models have been proposed to explain the frequency-dependent behavior, α1, of living cells. The abolishment of α1 caused by treatment with Glut, which makes all bonds covalent, eliminates the possibility of slow turnover of covalent bonds. Polymer entanglements, such as those of actin polymers, are also not possible, as their slopes are too high (α1 = 0.75). A recent report based on F-actin solution data proposes a “glassy wormlike chain” model to explain the origin of the weak power-law behavior of living cells (29). However, living cells still exhibit weak power laws in the absence of F-actin polymers, suggesting that F-actin may not be the only structure responsible for the weak power law. Furthermore, it is not clear how dependence of α2 on loading frequency can be explained by this model (see below). In a similar way, a model of many Kelvin-Voigt units is yet to be applied to explain α2 dependence on loading frequency (30). Crowding, caging, and jamming are not likely, because Glut treatment should not change these parameters significantly, since no new proteins are added or subtracted: only those protein polymers are cross-linked in space. Slow relaxation of protein structures may be dictated by hydrogen bonds or other noncovalent bonds within those structures (26), and thus these structures fall into the same category as the noncovalent bonds, although they are intramolecular rather than intermolecular bonds. Taken together, our model of noncovalent protein-protein interactions is the most viable candidate supported by living-cell experimental data. This model can predict living-cell rheology by collective behaviors of molecular noncovalent interactions of proteins. Our data suggest that this slow inelastic rearrangement originates from nonequilibrium processes associated with noncovalent protein-protein bonds. When the loading rate is much higher than the slow turnover rate of these noncovalent bonds, more and more of these bonds are trapped in the bound state, leading to a higher stiffness. This process appears to yield the appearance of the weak power law observed in living cells. That is, when the mechanical loading rates are much higher than the intrinsic relaxation rates of processes in cells, a single weak power law emerges.

The SGR model states that “glassy dynamics is a natural consequence of two properties shared by all soft materials: structural disorder and metastability” (1). Although this statement might be true for all soft glass materials, our model of multiple molecular adhesions of noncovalent bonds that are not disordered or metastable structures can also predict the weak power laws as well as the strong power laws for a wide range of loading rates or frequencies in living cells, suggesting that one does not need to invoke structural disorder/metastability to exhibit anomalous rheology in living cells. Our model includes fluid viscous contributions as well as a transition state between two energy wells that are not part of the original SGR model (1).

The critical rupture length (Lc) divided by the critical loading rate (Vc) yields the near-equilibrium time constant Tc. From those measured values in our model (Lc varied from 3 to 18 nm, corresponding to Vc of 0.02–0.00026 nm/μs, respectively), we can determine that Tc varied from 0.15 to 70 ms. Our model only deals with one parallel layer of protein-protein interactions (Fig. 1) (length scale ∼20 nm); in a spread cell where the cell thickness is ∼2 μm, there should be at least 100 layers of protein-protein interactions in series. The range for time constants, Tc, in living cells should then scale up to 15 ms (0.15 ms × 100) to 7 s (70 ms × 100), similar to that observed in living cells. If the time constants are dictated by the longest one in a living cell, then the predicted near-equilibrium time constant should be 7 s, right in the range of characteristic time constants (1–10 s) measured in living cells (12). In our model, loading times (length scales divided by loading rates) range from 1 μs to 1 s; scaling this up by using 100 layers of protein-protein interactions in series, they are equivalent to 100 μs to 100 s in the living cell situation, or 0.01–10,000 Hz. These frequencies are in a range similar to those applied in live-cell experiments. These analyses suggest that our MDS model is relevant with regard to loading frequencies and characteristic time constants in living cells.

The MDS model is built on first principles and thus is not a curve-fitting model. The strong association between the model and the living-cell data in terms of values of α1 and α2 is amazing in that all observed values of α1 and α2 in living cells can be predicted by the MDS model with varying depths of energy well barriers U1 and U2. In contrast, none of the models proposed thus far can explain α2 (e.g., the SGR model) or match magnitudes of α1 and α2 in living cells (e.g., the soft colloid model) (see below). One may ask the question: can the MDS model capture the realistic magnitudes of stiffness in living cells? First, the stiffness of the model depends on the number of molecules in parallel, which can be increased. Second, a published report demonstrates that although there are large differences in measured stiffness depending on the cell region being probed (cortical versus internal) and the technique being used (MTC, laser tracking microrheology, or two-point microrheology), the power-law slopes are all similar (6), which suggests that the power-law behavior is a unique feature that depends on loading frequency and is insensitive to stiffness magnitude.

The slope of the power law α1 depends largely on U1. When the energy well deepens (i.e., U1 increases), the power-law exponent α1 decreases. The deepening of U1 might result from the action of a catch bond (31,32). This provides a mechanistic explanation of the empirical relationship between the prestress and the power-law exponent α1: namely, α1 decreases when the active contractile prestress of the cell increases as myosin II-actin interactions increase (33). Our findings also suggest that the passive prestress imposed on the cell by external stretching would only increase the depth of the energy well U2, since this passive prestress increases only α2, not α1 (12). This is very different from the effects of the active contractile prestress. Therefore, passive prestress and active contractile prestress may have very different effects on the power-law exponents, although they both have stiffening effects on living cells. If we were right, then the higher α1 observed in ES cells compared with differentiated cells would suggest that ES cells have shallower intrinsic energy well depths, at least partly due to lower contractile prestress. This prediction could be tested in the future. Amazingly, cross-linking cellular proteins with Glut almost completely abolished α1. This suggests that noncovalent protein-protein bonds are responsible for the inelastic behavior of living cells. It is important to note that regardless of the underlying mechanisms for passive prestress and active prestress in modulating the power-law slopes, we have provided, at the molecular level, a physical mechanism for the weak power law of living cells.

The existing models cannot explain α2. It has been postulated that the power-law exponent α2 at lower loading frequency is due to active cellular remodeling processes or is related to specific cytoskeletal filament systems. However, jasplakinolide-treated cells exhibited similar power laws, suggesting that F-actin-dependent remodeling cannot explain α2 (12). Here, we show further that α2 cannot be due to active remodeling, since ATP-depleted cells exhibit similar α2. Moreover, our model data show that α2 originates from near-equilibrium processes between noncovalent protein-protein interactions and depends on both U1 and U2. In the low loading rate regime, as the loading rates become smaller than Vc, both log kon/koff and log koff influence the rupture force, because both the trapped population in the bound state and the repopulation of the bound state determine the effective rupture force and thus the dynamic stiffness, leading to a different power law in the model. This is the molecular basis of the strong power law. Cross-linking cellular proteins with Glut increased α2 in ASM cells. The cross-linking therefore greatly increased both U1 and U2 for the key protein-protein bonds in the cells. The crossover between α1 and α2 occurs near the nonequilibrium-to-equilibrium transition, as observed in MDS of both proteins and living cells, and consistent with live-cell data reported earlier (12). However, in its present form, the MDS model cannot predict the wide transition region in live cells (Fig. 3 C) (12). We speculate that the existence of several transition states between U1 and U2 among protein-protein bonds might be partly responsible for the wide transition region in living cells. It is possible that intrinsic association time constants of key noncovalent protein-protein bonds are on the order of seconds, which might dictate the range of near-equilibrium frequencies in the whole living cell. Therefore, it might not be a coincidence that physiologically relevant time constants in living cells are ∼1–10 s over different length scales. It is not clear at this time what these key proteins are, but candidates may include different cross-linking, bundling, and/or association proteins that are part of the stress dissipation pathway. The rupture of these key noncovalent protein-protein bonds and their reassociation may also partially explain the fluidization and resolidification of a living cell that is observed during a single stretch for a whole cell over several seconds (21).

Our MDS data strongly suggest that the two-power laws originate from noncovalent protein bonds, regardless of the protein identity, consistent with published results that the two-power laws are observed when stresses are applied via adhesion receptors or nonadhesion molecules (12). These findings indicate that two-power laws represent intrinsic material properties of living cells that are determined by noncovalent bonds of proteins. Noncovalent bonds (including hydrogen bonds, and Van der Waals, hydrophobic, and ionic interactions) are not strong, generally only a few to a dozen kT (28), which is the basis for our choice of MDS parameters U1 and U2. Due to thermal fluctuations, there are still significant dynamics, even when the loading frequency is well below the near-equilibrium frequency of critical processes in the cell. Therefore, at these very low loading frequencies, live cells are not “frozen” as suggested previously. Our data also suggest that the two-power-law behavior of live cells is not due to the mechanical behavior of a particular protein polymer (e.g., an actin polymer), as thought before (34). This is consistent with the finding that although the F-actin cytoskeleton contributes to the majority of the cell stiffness (22), it only contributes to power-law behavior at very high loading frequencies (>102 Hz) (4). A prestressed semiflexible actin polymer chain model has been proposed to explain the weak power-law rheology (35), but it is not clear how this model might be used to explain two-power-law behavior in living cells. In addition, activated myosin elevates F-actin polymer stiffness by two orders of magnitudes (36), but it remains to be seen whether this system, either alone or with other noncovalent bonds, exhibits two-power-law behavior. A recent report shows that α2 of soft microspheres has a value of ∼1.0 (like a fluid) at low loading frequencies (37), much higher than the values of α2 (0.6–0.7) that we observed in MDS and in living cells. Since these soft microspheres and other soft glassy materials (SGMs) are likely to be crowded, caged, and jammed, the inability of these microspheres to explain quantitatively living-cell data suggests that the model of crowding, caging, and jamming alone cannot explain α2 at long loading times. Thus, although some analogy may be drawn between SGMs and living cells (both exhibit multiple power laws), there might be some fundamental differences between the two. In SGMs, the interactions among particles are nonspecific in nature. In sharp contrast, in living cells, all noncovalent bonds that have long association times (hundreds of milliseconds to tens of seconds) are between specific proteins and DNA (38) or specific protein and protein interactions (e.g., cross-linking proteins, 39). For example, the association time constant between a transcription factor lac repressor and DNA (the lac operator) is ∼60 s, whereas the same protein interacts nonspecifically with other regions of DNA with a time constant of <5 ms (38). Furthermore, the myosin II association time constant in living cells is ∼10 s (39). It is interesting to note that even nuclei of stem cells and differentiated cells exhibit two-power-law rheological behaviors (40), although the values of α2 are different from those of whole cells observed in this study. Taken together, our data suggest that both α1 and α2 power-law exponents are intrinsic material properties of living cells, and that they originate from the nonequilibrium-to-near-equilibrium transition of the dynamic loading of protein-protein bonds in the cell. It is amazing that the weak power law of α1 and the strong power law of α2 can be predicted by MDS of noncovalent protein-protein interactions whose numbers are in the range of tens to hundreds. One need not invoke the idea of infinite time constants for the slope of α1.

The SGR model describes the dynamic feature of the cell mechanical properties (2–4), whereas the cellular tensegrity model describes prestress-dependent force balances in living cells (41–43). Our current findings suggest that at the molecular level, both the power-law dependence of cell stiffness and prestress-dependent cell stiffness can be explained by the depths of intrinsic energy well barriers and by the nonequilibrium-to-near-equilibrium transition between protein-protein noncovalent interactions. It is remarkable that although our MDS model is simple and protein-protein bonds in cells may involve many more states, it has captured the essential rheological features of live cells and provides a mechanistic basis of dynamics of live cell mechanics. Our recent report shows that rapid, long-distance transduction of forces to activate Src kinase occurs only when stresses are applied via activated integrins and the intact cytoskeleton (44). Therefore, it is not clear how analyses of general material properties of living cells can help elucidate molecular pathways of mechanotransduction. Nevertheless, this study is an attempt to understand, at the molecular level, the collective behaviors of bonds in response to forces in a living cell (45,46). Future study at the molecular level is needed to experimentally test our model and to incorporate molecular specificity into bonds to understand biochemical activities and biological responses to forces in living cells.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view all of the supplemental files associated with this article, visit www.biophysj.org.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. D. Stamenovic for fruitful discussion.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant GM072744 (N.W.) and by the University of Illinois (N.W.).

Editor: Richard E. Waugh.

References

- 1.Sollich, P. 1998. Rheological constitutive equation for a model of soft glassy materials. Phys. Rev. E Stat. Phys. Plasmas Fluids Relat. Interdiscip. Topics. 58:738–759. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fabry, B., G. N. Maksym, J. P. Butler, M. Glogauer, D. Navajas, and J. J. Fredberg. 2001. Scaling the microrheology of living cells. Phys. Rev. Lett. 87:148102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bursac, P., G. Lenormand, B. Fabry, M. Oliver, D. A. Weitz, V. Viasnoff, J. P. Butler, and J. J. Fredberg. 2005. Cytoskeleton remodeling and slow dynamics in the living cell. Nat. Mater. 4:557–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deng, L., X. Trepat, J. P. Butler, E. Millet, K. G. Morgan, D. A. Weitz, and J. J. Fredberg. 2006. Fast and slow dynamics of the cytoskeleton. Nat. Mater. 5:636–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alcaraz, J., L. Buscemi, M. Grabulosa, X. Trepat, B. Fabry, R. Farré, and D. Navajas. 2003. Microrheology of lung epithelial cells measured by atomic force microscopy. Biophys. J. 84:2071–2079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoffman, B. D., G. Massiera, K. M. Van Citters, and J. C. Crocker. 2006. The consensus mechanics of cultured mammalian cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 103:10259–10264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Giannone, G., and M. P. Sheetz. 2006. Substrate rigidity and force define form through tyrosine phosphatase and kinase pathways. Trends Cell Biol. 16:213–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vogel, V., and M. Sheetz. 2006. Local force and geometry sensing regulate cell functions. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 7:265–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giannone, G., B. J. Dubin-Thaler, H. G. Döbereiner, N. Kieffer, A. R. Bresnick, and M. P. Sheetz. 2004. Periodic lamellipodial contractions correlate with rearward actin waves. Cell. 116:431–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hu, S., and N. Wang. 2006. Control of stress propagation in the cytoplasm by prestress and loading frequency. Mol. Cell. Biomech. 3:49–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mack, P. J., M. R. Kaazempur-Mofrad, H. Karcher, R. T. Lee, and R. D. Kamm. 2004. Force-induced focal adhesion translocation: effects of force amplitude and frequency. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 287:C954–C962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stamenović, D., N. Rosenblatt, M. Montoya-Zavala, B. D. Matthews, S. Hu, B. Suki, N. Wang, and D. E. Ingber. 2007. Rheological behavior of living cells is timescale-dependent. Biophys. J. 93:L39–L41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Panettieri, R. A., R. K. Murray, L. R. DePalo, P. A. Yadvish, and M. I. Kotlikoff. 1989. A human airway smooth muscle cell line that retains physiological responsiveness. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 256:C329–C335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hu, S., J. Chen, B. Fabry, Y. Numaguchi, A. Gouldstone, D. E. Ingber, J. J. Fredberg, J. P. Butler, and N. Wang. 2003. Intracellular stress tomography reveals stress focusing and structural anisotropy in cytoskeleton of living cells. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 285:C1082–C1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Auerbach, W., J. H. Dunmore, V. Fairchild-Huntress, Q. Fang, A. B. Auerbach, D. Huszar, and A. L. Joyner. 2000. Establishment and chimera analysis of 129/SvEv- and C57BL/6-derived mouse embryonic stem cell lines. Biotechniques. 29:1024–1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tompers, D. M., and P. A. Labosky. 2004. Electroporation of murine embryonic stem cells: a step-by-step guide. Stem Cells. 22:243–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tanaka, T. S., T. Kunath, W. L. Kimber, S. A. Jaradat, C. A. Stagg, M. Usuda, T. Yokota, H. Niwa, J. Rossant, and M. S. Ko. 2002. Gene expression profiling of embryo-derived stem cells reveals candidate genes associated with pluripotency and lineage specificity. Genome Res. 12:1921–1928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tanaka, T. S., I. Lopez de Silanes, L. V. Sharova, H. Akutsu, T. Yoshikawa, H. Amano, S. Yamanaka, M. Gorospe, and M. S. Ko. 2006. Esg1, expressed exclusively in preimplantation embryos, germline, and embryonic stem cells, is a putative RNA-binding protein with broad RNA targets. Dev. Growth Differ. 48:381–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nagy, A., M. Gertsenstein, K. Vintersten, and R. Behringer. 2003. Manipulating the Mouse Embryo: A Laboratory Manual, 3rd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, New York.

- 20.Bain, G., D. Kitchens, M. Yao, J. E. Huettner, and D. I. Gottlieb. 1995. Embryonic stem cells express neuronal properties in vitro. Dev. Biol. 168:342–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Trepat, X., L. Deng, S. S. An, D. Navajas, D. J. Tschumperlin, W. T. Gerthoffer, J. P. Butler, and J. J. Fredberg. 2007. Universal physical responses to stretch in the living cell. Nature. 447:592–595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang, N., J. P. Butler, and D. E. Ingber. 1993. Mechanotransduction across the cell surface and through the cytoskeleton. Science. 260:1124–1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mijailovich, S. M., M. Kojic, M. Zivkovic, B. Fabry, and J. J. Fredberg. 2002. A finite element model of cell deformation during magnetic bead twisting. J. Appl. Physiol. 93:1429–1436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li, F., and D. Leckband. 2006. Dynamic strength of molecularly bonded surfaces. J. Chem. Phys. 125:194702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li, F. 2007. Molecular basis of cell adhesion mechanics. PhD thesis. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, IL.

- 26.Sotomayor, M., and K. Schulten. 2007. Single-molecule experiments in vitro and in silico. Science. 316:1144–1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brujic, J., R. I. Hermans, K. A. Walther, and J. M. Fernandez. 2006. Single-molecule force spectroscopy reveals signatures of glassy dynamics in the energy landscape of ubiquitin. Nat. Phys. 2:282–286. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lodish, H., A. Berk, P. Matsudaira, C. A. Kaiser, M. Krieger, M. P. Scott, L. Zipursky, and J. Darnell. 2004. Molecular Cell Biology, 5th ed. W. H. Freeman and Company, New York.

- 29.Semmrich, C., T. Storz, J. Glaser, R. Merkel, A. R. Bausch, and K. Kroy. 2007. Glass transition and rheological redundancy in F-actin solutions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 104:20199–20203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Balland, M., N. Desprat, D. Icard, S. Féréol, A. Asnacios, J. Browaeys, S. Hénon, and F. Gallet. 2006. Power laws in microrheology experiments on living cells: comparative analysis and modeling. Phys. Rev. E Stat. Nonlin. Soft Matter Phys. 74:021911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhu, C., and R. P. McEver. 2005. Catch bonds: physical models and biological functions. Mol. Cell Biomech. 2:91–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guo, B., and W. H. Guilford. 2006. Mechanics of actomyosin bonds in different nucleotide states are tuned to muscle contraction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 103:9844–9849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stamenović, D., B. Suki, B. Fabry, N. Wang, and J. J. Fredberg. 2004. Rheology of airway smooth muscle cells is associated with cytoskeletal contractile stress. J. Appl. Physiol. 96:1600–1605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gardel, M. L., J. H. Shin, F. C. MacKintosh, L. Mahadevan, P. Matsudaira, and D. A. Weitz. 2004. Elastic behavior of cross-linked and bundled actin networks. Science. 304:1301–1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rosenblatt, N., A. M. Alencar, A. Majumdar, B. Suki, and D. Stamenović. 2006. Dynamics of prestressed semiflexible polymer chains as a model of cell rheology. Phys. Rev. Lett. 97:168101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mizuno, D., C. Tardin, C. F. Schmidt, and F. C. Mackintosh. 2007. Nonequilibrium mechanics of active cytoskeletal networks. Science. 315:370–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wyss, H. M., K. Miyazaki, J. Mattsson, Z. Hu, D. R. Reichman, and D. A. Weitz. 2007. Strain-rate frequency superposition: a rheological probe of structural relaxation in soft materials. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98:238303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Eif, J., G. W. Li, and X. S. Xie. 2007. Probing transcription factor dynamics at the single-molecule level in a living cell. Science. 316:1191–1194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reichl, E. M., R. Ren, M. K. Morphew, M. Delannoy, J. C. Effler, K. D. Girard, S. Divi, P. A. Iglesias, S. C. Kuo, and D. N. Robinson. 2008. Interactions between myosin and actin crosslinkers control cytokinesis contractility dynamics and mechanics. Curr. Biol. 18:471–480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pajerowski, J. D., K. N. Dahl, F. L. Zhong, P. J. Sammak, and D. E. Discher. 2007. From the cover: physical plasticity of the nucleus in stem cell differentiation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 104:15619–15624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ingber, D. E. 2003. Tensegrity I. Cell structure and hierarchical systems biology. J. Cell Sci. 116:1157–1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang, N., K. Naruse, D. Stamenović, J. J. Fredberg, S. M. Mijailovich, I. M. Tolić-Nørrelykke, T. Polte, R. Mannix, and D. E. Ingber. 2001. Mechanical behavior in living cells consistent with the tensegrity model. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 98:7765–7770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang, N., I. M. Tolić-Nørrelykke, J. Chen, S. M. Mijailovich, J. P. Butler, J. J. Fredberg, and D. Stamenović. 2002. Cell prestress. I. Stiffness and prestress are closely associated in adherent contractile cells. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 282:C606–C616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Na, S., O. Collin, F. Chowdhury, B. Tay, M. Ouyang, Y. Wang, and N. Wang. 2008. Rapid signal transduction in living cells is a unique feature of mechanotransduction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 105:6626–6631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Evans, E., and D. A. Calderwood. 2007. Forces and bond dynamics in cell adhesion. Science. 316:1148–1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Johnson, C. P., H. Y. Tang, C. Carag, D. W. Speicher, and D. E. Discher. 2007. Forced unfolding of proteins within cells. Science. 317:663–666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Desprat, N., A. Richert, J. Simeon, and A. Asnacios. 2005. Creep function of a single living cell. Biophys. J. 88:2224–2233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.