Abstract

Conformational transitions between open/closed or free/bound states in proteins possess functional importance. We propose a technique in which the collective modes obtained from an anisotropic network model (ANM) are used in conjunction with a Monte Carlo (MC) simulation approach, to investigate conformational transition pathways and pathway intermediates. The ANM-MC technique is applied to adenylate kinase (AK) and hemoglobin. The iterative method, in which normal modes are continuously updated during the simulation, proves successful in accomplishing the transition between open-closed conformations of AK and tense-relaxed forms of hemoglobin (Cα− root mean square deviations between two end structures of 7.13 Å and 3.55 Å, respectively). Target conformations are reached by root mean-square deviations of 2.27 Å and 1.90 Å for AK and hemoglobin, respectively. The intermediate conformations overlap with crystal structures from the AK family within a 3.0-Å root mean-square deviation. In the case of hemoglobin, the transition of tense-to-relaxed passes through the relaxed state. In both cases, the lowest-frequency modes are effective during transitions. The targeted Monte Carlo approach is used without the application of collective modes. Both the ANM-MC and targeted Monte Carlo techniques can explore sequences of events in transition pathways with an efficient yet realistic conformational search.

INTRODUCTION

The function of a protein is closely related to the conformational ensemble accessible to its three-dimensional structure. Proteins may undergo conformational changes while performing biological functions, such as catalysis, regulation, and transportation. Understanding such biological events relies on the elucidation of transitional complexes and pathways (1,2). A powerful experimental technique does not yet exist for determining the ensemble of conformational transition pathways between two known conformations of a protein. NMR technique is used to attain an average structure among an ensemble of conformations. NMR explores highly populated conformations, but fails to distinguish between less populated intermediate conformations (2). In this respect, atomistic and coarse-grained simulation techniques have gained considerable interest (3,4).

Atomistic simulation techniques that make use of all-atom empirical potentials (5), such as molecular dynamics (MD) and normal mode analysis (NMA), become computationally inefficient as the system size increases. Currently, MD simulations that can reach up to nanoseconds or at most a few microseconds are not suitable for the exploration of conformational changes in the timescale of microseconds/milliseconds to seconds. For this purpose, targeted MD simulations (TMD) (6–9) are adopted to simulate large conformational transitions by biasing the conventional MD technique to sample the conformational space in a predefined direction. It is based on a knowledge of both the initial and end structures, and on performing an MD simulation starting from one conformational state as the initial structure and using the root mean-square deviation (RMSD) from the end state for a directing, i.e., biasing constraint (6). The TMD proved successful at finding continuous pathways for investigated transitions. However, it does not always yield reversible pathways, and necessarily follows the lowest energy pathway (8). As an alternative to atomistic models, coarse-grained approaches, such as elastic network models (ENMs) and Monte Carlo (MC) simulation techniques, may be efficient tools for the analysis of large proteins and their complexes.

Such ENM-based approaches as Gaussian network models (GNMs) (10–14) and anisotropic network models (ANMs) (15) were successful in reproducing collective modes and atomic fluctuations for even supramolecular assemblages. The ENM is basically a low-resolution NMA, where harmonic potentials are used to connect close-neighboring residues in the coarse-grained protein structure. In general, a single low-frequency mode direction from the NMA closely overlaps with the open/free to closed/bound conformational transitions of proteins (16). Thus, classical or preferably coarse-grained NMAs are used to explore conformational transitional pathways (1,17–23).

A common example involves the transitional pathways of hemoglobin, as addressed in several computational studies. Based on an initial NMA of the T structure of hemoglobin (17), this structure was successively deformed along certain low-frequency eigenmodes (both positive and negative directions), and each deformation was followed by energy minimization. Four intermediate structures were proposed between tense-relaxed (T-R) states, and a maximum approach to the R state was 1.82 Å. In a somewhat similar study (20), a transition from T to R2 in hemoglobin was reported using the most global (slowest) ANM mode, with an approach of 2.4 Å to the R2 state. Another study (18) performed MD simulations with path-exploration and distance-constraints methods to achieve the T-R transition in hemoglobin.

Maragakis and Karplus (21) developed the plastic network model (PNM) as an extension of ENMs, to generate a minimum energy path between two structures. The authors proposed a transitional pathway for adenylate kinase (AK) by comparing 25 deposited Protein Data Bank (PDB) entries, including 45 different conformers of AK in total with their simulation trajectory intermediates. They suggested that a set of crystal structures (within a maximum 3-Å deviation with their model intermediates) were possibly present in the pathway. Zheng and Brooks (22,23) proposed a method, again based on ENM, that uses the crystal structure of the initial state and several distance constraints for the end state. The method, which iteratively minimizes the error of fitting the given distance constraints as well as the energy cost, proved successful in maintaining the associated transitions in a set of 16 protein structures. In a combined block normal mode-Monte Carlo (MC) scheme (24), the folding of small, helical proteins was achieved with a 5–6-Å RMSD to the target by applying constraints based on scattering profiles and fixing the helical regions.

Several hybrid strategies have combined the different approaches summarized above, to enhance the conventional techniques in terms of computational efficiency. One such approach, the so-called amplified collective motion (ACM), was proposed by Zhang et al. (25) and He et al. (26). The method uses ENM-derived normal modes for accelerating the conformational sampling of MD simulations (25,26), and was successfully applied to the bacteriophage T4 lysozyme and villin headpiece subdomain (HP-36).

In previous applications of NMA (either atomistic or coarse-grained), the successive deformations to investigate conformational transition pathways were based on the collective modes of the initial structure (17,20). Nevertheless, as the initial conformation is deformed, the eigenvectors from the NMA of the initial structure become less accurate in representing the global motions of the new intermediate structures (23). Thus, these methods may provide only a few intermediate conformations (27), and in reality may not yield a complete transition pathway between two end conformations. Moreover, NMA applications provide information about the collective motions of a protein, but do not provide insights into the sequence of these physical events and the intermediate complexes.

We present what to our knowledge is a new approach that incorporates the collective deformation directions obtained from ANM into an MC simulation technique, based on the knowledge-based potentials of proteins (28–30). To investigate the conformational transition pathways of proteins in a computationally efficient way, we propose an iterative methodology composed of ANM and MC cycles to approach the target conformations. In each cycle, the normal modes are calculated, based on the initial structure, and then the slow mode overlapping the desired transition is selected. As a result, a new structure is generated by deforming the structure along the chosen mode. The energy of the new structure is then minimized by the MC technique, and the initial structure is updated for the next cycle. The novel approach described here prevails over the limitations of previous applications by repeating the NMA periodically throughout the simulation, and by using the updated normal modes of the present state. Consequently, by repeated NMAs followed by energy minimization using the MC technique, our methodology could possibly generate a more feasible pathway between two conformations with short computational times. Application of the method to two very frequently studied allosteric proteins, i.e., Escherichia coli AK and human hemoglobin, allowed for comparisons with previous findings in the literature. This approach improves both the ANM and MC techniques in the sense of providing information about the sequence of events as well as a more efficient conformational search, hence offering a promising tool for modeling large biological systems.

METHODS

Anisotropic network model

The ANM (15) is a coarse-grained NMA tool, commonly used to determine vibrational motions in proteins. By considering the three-dimensional anisotropy of the residue fluctuations, ANM predicts the directions of collective motions that provide information about the biological function of a protein and its mechanism of action. In the elastic-network representation of a protein, all pairs of coarse-grained sites/nodes that are closer than a cutoff distance, rc (usually 13–18 Å), are connected by harmonic springs that sum up to the potential energy:

|

(1) |

In Eq. 1, h(x) is the heavyside step function (h(x) = 1 if x ≥ 0, and zero otherwise), Rij is the distance between sites i and j, γ is the universal force constant, and  is the fluctuation in the position vector Ri of site i (

is the fluctuation in the position vector Ri of site i ( ). Usually each amino-acid residue is represented by a single interaction site (node) located at the Cα atom, but other levels of coarse-graining are also possible (31). Thus, the potential energy of a structure with N interaction sites-residues is expressed in matrix notation as:

). Usually each amino-acid residue is represented by a single interaction site (node) located at the Cα atom, but other levels of coarse-graining are also possible (31). Thus, the potential energy of a structure with N interaction sites-residues is expressed in matrix notation as:

|

(2) |

Here, ΔR is a 3N-dimensional vector of the position vector fluctuations ΔRi including all sites (1 ≤ i ≤ N), ΔRT is its transpose, and H is the (3N × 3N) Hessian matrix. The decomposition of H yields (3N − 6) nonzero eigenvalues, and (3N − 6) eigenvectors that give the respective frequencies and harmonic deformation directions of individual modes (the first 6 modes are associated with rigid body motion, i.e., translation and rotation are zero).

Monte Carlo simulation

In our coarse-grained MC technique (28–30), the backbone of the protein structure is represented by the virtual bond model (32). For a protein consisting of N residues, the conformation of the backbone is defined by 3N − 6 variables: N − 1 backbone virtual bonds, N − 2 bond angles θi, and N − 3 bond torsional angles φi. Each residue is represented by two interaction sites, its Cα atom, and its center-of-mass of the side chain (SC).

Knowledge-based potentials are used to calculate the energy of a given protein conformation with the contributions from two types of interactions: long-range (LR) interactions (33) between nonbonded residues that are close in space, and short-range (SR) interactions (28,34) between covalently bonded units along the chain sequence. During an MC step (MCS), a randomly chosen site, either a Cα or an SC site, is subjected to a differential perturbation, using a uniformly distributed random number generator. The new perturbed conformation is accepted or rejected according the Metropolis criterion. One MCS is defined as N perturbations, and may be viewed as the average time for all N residues of the protein to have a chance to move. An MC algorithm with only local moves in some cases could provide insights into the real time of a process. However, there is no correspondence between the MCS and real time in our algorithm, because of the implementation of both global deformations and local moves. In general, multiple independent runs have been necessary for efficient sampling of the conformational space.

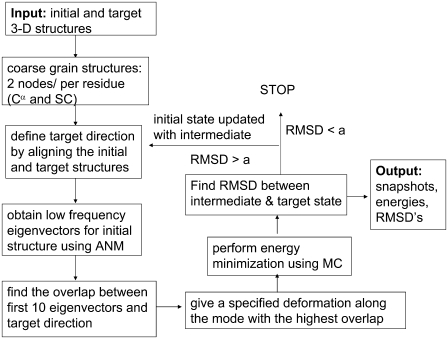

New methodology: ANM-MC simulation

In our scheme, we successively use ANM to provide collective deformation directions, and short MC runs to provide energy minimization on the deformed conformations. A schematic flowchart of the method developed is provided in Fig. 1. The algorithm requires the crystal structures of the initial and final/target states as inputs. The initial state may be the apo/open conformation of a protein, and the final state may be the bound/closed conformation. Atomistic structures are first coarse-grained by assigning two nodes for each residue: the α-carbon and the center of mass of the side chain, in accordance with the knowledge-based potentials used. For glycine, only one node (α-carbon) is taken into account. Hence the dimension of the system is 2N for a protein of N residues, excluding glycine residues. The target structure is then aligned on the initial structure, based on α-carbon coordinates. The target direction (Q), which is a 3N-dimensional vector comprised of α-carbon coordinate deformations, is calculated by subtracting the initial coordinates from the aligned coordinates of the target.

FIGURE 1.

Flowchart of ANM-MC algorithm. See Methods for details.

The ANM is applied to the initial structure to extract the 10 lowest-frequency eigenmodes using the Block Lanczos Package (BLZPACK), a Fortran 77 implementation of the block Lanczos algorithm for solving the standard eigenvalue problem by providing a set of eigenvectors (35–37). The cutoff is taken to be 18 Å in ANM calculations, using only α-carbon coordinates. The dot products of the 10 eigenvectors with the target direction are computed (considering both positive and negative directions), and the eigenvector U giving the highest dot-product overlap with the target direction Q is determined. A new conformation is generated by deforming the initial structure along this mode direction, using a prespecified deformation factor (DF = 0.1–0.5 Å in this work). We can express this as: Rnew = R ± U × DF. Here, Rnew and R denote the coordinate matrix of the new conformation generated and the initial state, respectively. In this study, we considered the DF to be such that we obtain an average motion with a desired RMSD from the initial state upon deformation.

Although ANM is performed using α-carbon atoms, the structure is deformed along the selected mode direction by applying the same deformation to the α-carbon and side-chain nodes of each residue. The deformed conformation is allowed to relax by a specified number of MC steps (MCS = 100, 500, or 1000). The RMSD between the energy-minimized new structure and the target structure is calculated. If the RMSD is smaller than a desired value (a), the simulation stops. If not, the simulation enters a new iteration after the initial state is updated with the output from the previous MC step. Obviously, the target vector is also updated at each iteration, based on the modification of the initial state.

The ANM-MC simulation is performed using an automated method after providing the x-ray structures of the initial and end states of a protein and the necessary parameters, i.e., the DF and the number of MC steps (MCS) to be used at each iteration, and the cutoff distance for ANM calculations (rc = 18 Å). An initial parameter-optimization stage is required to determine suitable ranges for the DF and MCS. Here, ANM-MC is applied first to AK, for which there exists a proposed conformational transition pathway from the open to closed conformation (21). Next, the method is applied to another frequently studied allosteric protein, human hemoglobin.

Targeted Monte Carlo simulation

To analyze the significance of using normal modes, ANM calculations are omitted from the algorithm (Fig. 1). After the target direction is calculated, the new conformation is generated by giving a certain deformation in that target direction without performing ANM. The new conformation is again relaxed by MC, and the rest of the algorithm is the same. As in the case of the ANM-MC protocol, the simulation parameters are DF and MCS in the targeted Monte Carlo (TMC) method.

This technique is similar to the targeted molecular dynamics (TMD) simulations that have gained considerable attention (6–9). In short, the MC conformational search is now targeted absolutely in the direction of the desired conformational transition, which is similar to the morphing algorithms (38), where the path between the two end conformations is linearly interpolated together with energy minimization, to conserve the chemical structure. In TMC, each intermediate is subjected to a certain number of MCS, with a potential function of both short and long-range interactions. Because this may lead to conformational changes at each step, the resulting conformations may not correspond to the interpolated points between the two end conformations.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Adenylate kinase as a test case

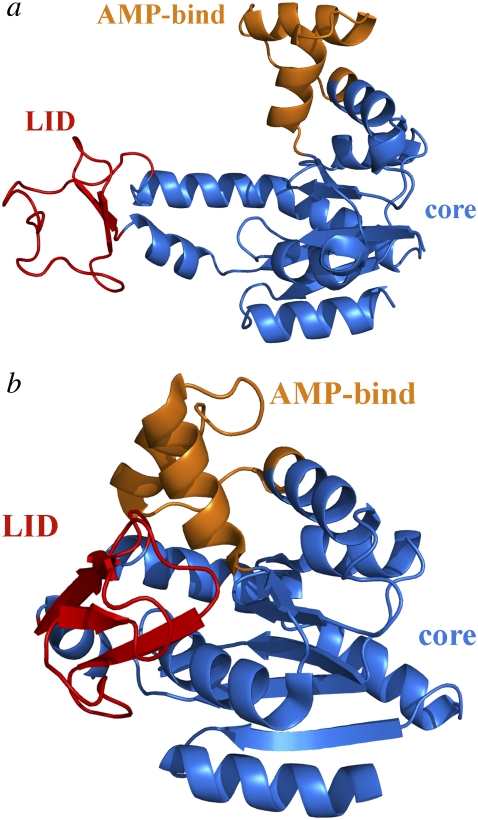

The E. coli AK is a 214-residue protein belonging to the nucleoside monophosphate (NMP) kinases that catalyze the transfer of the terminal phosphoryl group from ATP to AMP. Adenylate kinase involves three domains, i.e., a core domain, an ATP-binding or LID domain (residues 122–158), and an AMP-binding (AMP-bind) domain (residues 30–63). During catalysis, the core domain of AK is mainly preserved, unlike the LID and AMP-bind domains that undergo large conformational changes (39–41). Adenylate kinase is known to attain two unique conformations, i.e., open and closed states (Fig. 2). In Fig. 2, the core, LID, and AMP-bind domains are shown in blue, red, and orange, respectively. In the apo/unligated structure, the ATP-bind and AMP-bind domains assume open conformations (Fig. 2 a; PDB code 4AKE) (41). A closed conformation (Fig. 2 b), crystallized with the inhibitor AP5A, is also available (PDB code 1AKE) (40). We chose the first conformers (chain A) in both x-ray structures (including two chains), and did not take into consideration the water molecules and ligand atoms. For the evaluation of our technique, AK was chosen primarily because of its large conformational change (RMSD between open and closed structures = 7.13 Å) and the availability of a large amount of experimental and computational data.

FIGURE 2.

Ribbon diagrams for (a) apo/open conformation of AK (PDB code 4AKE) and (b) bound/closed conformation of AK (PDB code 1AKE), as generated by PyMOL (56). The LID (122–158, red) and AMP-bind (30–63, orange) domains undergo a large conformational change upon binding with an RMSD of 7.13 Å between open and closed structures. Core domain (blue) does not exhibit a significant change.

Parameter adjustment: RMSD and energy profiles in AK

Before applying our methodology, the collective modes of the open form of AK were studied by ANM, and visual interpretations of the collective modes were performed by using our web server HingeProt (42). The slowest two modes were associated with motion in the LID domain, i.e., LID closing. In the higher modes, such as the third and fourth eigenmodes, LID closing was accompanied by AMP-bind domain closing. However, ANM itself does not provide information about the sequence of these events, i.e., which domain closes first.

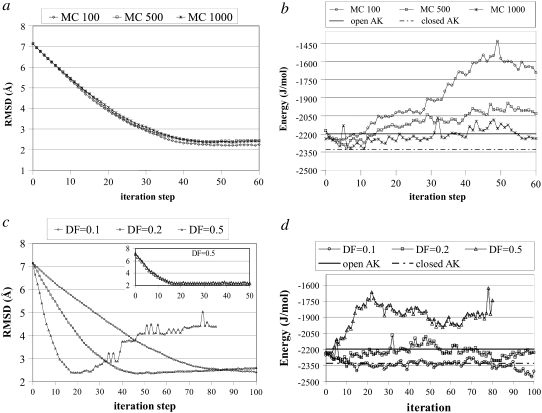

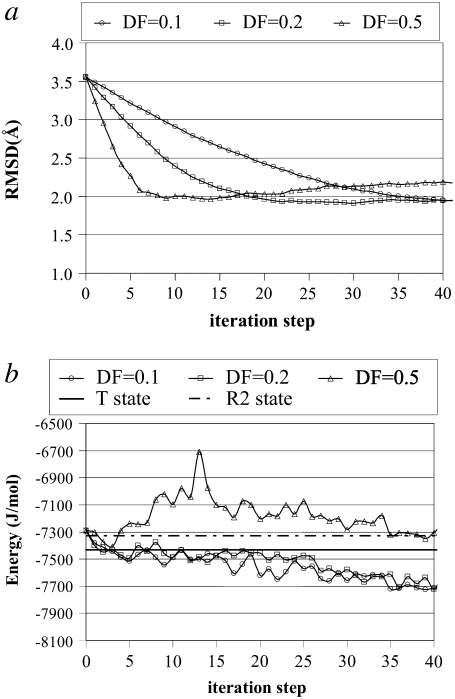

Using the new algorithm, we intended to reach the closed conformation of AK (1AKE), starting with the open one (4AKE). For parameter optimization, runs were performed using different DFs of 0.1, 0.2, and 0.5 Å along the ANM modes, and different numbers of MCS (MCS = 100, 500, and 1000) for energy minimization at each iteration. Three independent runs were performed for each combination of DF and MCS, but results are shown for a single run because of the similarity of different runs. Fig. 3 presents the simulation results obtained for the transition from the open to the closed (target) conformation of AK. In all cases, the x axis represents the number of ANM-MC iterations or cycles. Thus, one iteration/cycle represents an ANM calculation with the specified DF followed by an MC simulation of certain steps (MCS = 100, 500, or 1000), as shown in Fig. 1.

FIGURE 3.

RMSD and energy values as a function of iteration/cycle number for various AK runs from open to closed states. (a) Effect of number of MCS on RMSD values. The x axis is number of iteration steps (1 step meaning an ANM calculation followed by either 100, 500, or 1000 MCS energy minimization), and the y axis is for the RMSD between the structure obtained at the end of the corresponding iteration step and the target form (1AKE). Deformation factor is 0.2 Å. Energy minimization after each iteration of NMA is 100, 500, and 1000 MCS. (b) Effect of number of MCS on total energies of intermediate structures during simulation (DF = 0.2 Å in each case). Open (initial) and closed (target) conformations are relaxed by 1000 MCS, and average values are plotted on horizontal lines. (c) RMSD of intermediate structures to target structure with various DFs (0.1, 0.2, and 0.5 Å), followed by 1000-MCS energy minimization in each case. With a smaller DF, e.g., 0.1 or 0.2 Å, smoother and nonoscillating profiles are attained, compared with higher DFs. (d) Corresponding energy profiles of AK during simulation with various DFs.

In Fig. 3 a, the effect of MCS on RMSD profiles is plotted for a fixed DF = 0.2 Å. The RMSDs between the energy-minimized intermediate structures and the target structure are calculated based on Cα coordinates at the end of each iteration. The RMSD value starts from 7.13 Å (the value between 4AKE and 1AKE), and smoothly decreases up to 2.27 Å (MCS = 100), 2.29 Å (MCS = 500), and 2.34 Å (MCS = 1000), indicating a reasonable approach to the closed conformer. No significant difference can be observed in the RMSD profiles obtained for different MCS.

Fig. 3 b demonstrates the effect of MCS on the total energy profiles (total energy = (short range) SR + long-range (LR) energies; see Methods) of the intermediate structures throughout the simulation with DF = 0.2 Å. The x-ray structures of the open and closed conformers of AK are also relaxed by MC, and for comparison, their average energies at MCS = 1000 are depicted in Fig. 3 as horizontal lines. The energy of the closed conformation (1AKE) is lower than that of the open conformation (4AKE). In contrast to the RMSD profiles, the total energies of these intermediates differ considerably with the MCS employed. Specifically, 1000 MCS in each cycle result in structures with lower energies that fall in the range of open and closed structure energies. Because the backbone structures of these intermediates are similar due to their close RMSD values, the reason for these energy differences should be apparent in terms of side-chain orientations. Indeed, the total LR and side-chain SR interactions (associated with side-chain bond stretching, angle bending, and bond torsion) obtained with longer energy minimizations are lower than those of the shorter runs (not shown), leading to lower total energies. As a result, an MC step of 1000 is found to be optimal for energy minimization. Even longer MC runs could be used in each cycle, but that would decrease the computational efficiency of the new protocol.

In Fig. 3 c, the effect of DF on RMSD profiles is demonstrated for constant MCS = 1000. Smoothly decreasing RMSD profiles are obtained with smaller DFs such as 0.1 or 0.2 Å. The closest approaches to the closed conformer are 2.27 and 2.34 Å at the 104th and 47th cycles, with DF = 0.1 and 0.2 Å, respectively. Higher DFs (DF = 0.5 Å) lead to trajectories that approach the target faster (minimum RMSD = 2.38 at the 21st cycle), but show a subsequent increase in RMSD. This unstable behavior around the target is attributable to deforming the structure about slow mode directions that have, in fact, very low overlap values with the target direction after the initial decrease in RMSD, which we will discuss below. Hence, for closer approaches and stable RMSD profiles, smaller DFs, such as 0.1 and 0.2 Å, are chosen as suitable. However, applying DF = 0.5 until the closest approach to the target (minimum RMSD) is achieved, and then using smaller DFs such as 0.1 (Fig. 3 c, inset), results in smoothly decreasing and nonoscillatory RMSD profiles.

In Fig. 3 d, the effect of DF on energy profiles attained during simulations with MCS = 1000 is presented. Smaller DFs (0.1 or 0.2 Å) provide energy values that fall in the range of initial and target structure energies. However, quite reasonable energy profiles may be obtained with the higher DF = 0.5 Å as well, if longer energy minimizations, such as for 3000 MCS, are performed.

Among the different parameter combinations employed for AK, DF = 0.1 and 0.2 Å are appropriate choices with MCS = 1000. It is necessary to investigate whether or not the choice of these parameters significantly alters the transitional pathways obtained.

Transition pathway and pathway intermediates of AK

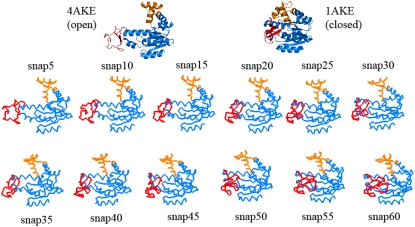

Fig. 4 illustrates several snapshots, up to the 60th iteration from the trajectory with DF = 0.2 Å and MCS = 1000. During initial cycles of the trajectory (up to around snapshot 30), the mobile LID domain (Fig. 4, red) slowly closes over the core domain (Fig. 4, blue). When the LID closing is almost accomplished, the AMP-bind domain (Fig. 4, orange) begins to bend over the core. However, complete closure of the AMP-bind domain is not evident here. Visual investigation of the snapshots reveals that the LID domain is more mobile compared with the AMP-bind domain, and closure of the LID seems to precede that of the AMP-bind domain.

FIGURE 4.

Several intermediate structures obtained during simulation of AK transition from open to closed conformation obtained for simulation with DF = 0.2, MCS = 1000 (snap = snapshot). LID domain (red) closure precedes AMP-bind domain bending motion (orange region).

The reliability of our intermediate structures is validated by comparison with the plastic network model results for AK (21). Table 1 tabulates the RMSD values between our simulation snapshots (Fig. 4) and the crystal structures proposed by Maragakis and Karplus (21) to be present as intermediates in the AK transition pathway. The RMSD values indicated in boldface in Table 1 represent the maximum approaches attained among the selected snapshots to the specific x-ray structures. The last two rows (Table 1) list the RMSDs between the open (4AKE) and closed (1AKE) structures and the rest of the crystal structures studied.

TABLE 1.

RMSD values between simulation snapshots (DF = 0.2 Å and MCS = 1000) and several AK crystal structures

| Snapshot/iteration | 4AKE | 1AK2* | 2AK2* | 1DVR,†B chain | 1DVR,† A chain | 1E4Y,‡ A chain | 1E4V,§ A chain | 1ANK,¶ A chain | 2ECK,‖ A chain | 1AKE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | 2.09 | 4.09 | 3.98 | 4.21 | 4.10 | 5.93 | 6.23 | 6.25 | 6.31 | 6.25 |

| 10 | 2.71 | 3.55 | 3.45 | 3.51 | 3.35 | 5.19 | 5.46 | 5.44 | 5.53 | 5.47 |

| 15 | 3.63 | 2.98 | 2.96 | 2.86 | 2.67 | 4.49 | 4.70 | 4.65 | 4.75 | 4.71 |

| 20 | 4.46 | 3.14 | 3.12 | 2.53 | 2.38 | 3.92 | 4.05 | 3.99 | 4.08 | 4.05 |

| 25 | 5.04 | 3.45 | 3.44 | 2.54 | 2.36 | 3.40 | 3.49 | 3.44 | 3.52 | 3.49 |

| 30 | 5.30 | 3.64 | 3.62 | 2.73 | 2.60 | 2.98 | 3.09 | 3.06 | 3.14 | 3.09 |

| 35 | 5.73 | 3.98 | 3.97 | 2.75 | 2.63 | 2.66 | 2.74 | 2.71 | 2.76 | 2.74 |

| 40 | 6.23 | 4.17 | 4.18 | 2.92 | 2.81 | 2.52 | 2.50 | 2.47 | 2.51 | 2.49 |

| 45 | 6.56 | 4.54 | 4.53 | 3.26 | 3.12 | 2.38 | 2.42 | 2.38 | 2.40 | 2.34 |

| 50 | 6.94 | 4.84 | 4.85 | 3.55 | 3.42 | 2.46 | 2.36 | 2.37 | 2.38 | 2.37 |

| 55 | 6.95 | 4.96 | 4.97 | 3.54 | 3.41 | 2.43 | 2.39 | 2.34 | 2.30 | 2.38 |

| 60 | 7.02 | 4.95 | 4.97 | 3.51 | 3.40 | 2.50 | 2.42 | 2.40 | 2.30 | 2.41 |

| 4AKE | 0.00 | 5.38 | 5.28 | 5.78 | 5.63 | 7.20 | 7.64 | 7.66 | 7.23 | 7.13 |

| 1AKE | 7.13 | 5.57 | 5.53 | 4.02 | 3.92 | 0.93 | 0.65 | 0.45 | 0.28 | 0.00 |

1AK2 and 2AK2 (43) belong to bovine mitochondria intermembrane space AK.

1DVR (A and B chains) (44) belong to baker's yeast AK.

1E4Y (45) is the glycine-loop modified version of AK from E. coli.

1E4V (45) is G10V mutant of AK from E. coli.

1ANK (39) is AMPPNP and AMP-bound form of AK from E. coli.

2ECK (46) is AMP-bound and ADP-bound form of AK from E. coli.

Earlier snapshots (iterations up to 30) exhibit maximum approaches to the crystal structures: 1AK2, 2AK2, 1DVR (B chain), and 1DVR (A chain), sequentially. In 1AK2 and 2AK2, the LID domain is about to close over the core, whereas the AMP-bind region is completely open. In 1DVR (A and B chains), the LID region is totally closed, whereas the AMP-bind is still open. Hence, the overlap of these four structures with the earlier snapshots indicates the priority of LID closing. Subsequent snapshots (iterations >30) fall into proximity with the rest of the four crystal structures, i.e., 1E4Y(A chain), 1E4V (A chain), 1ANK (A chain), and 2ECK (A chain). These crystal structures bear a close resemblance to the closed conformer 1AKE, i.e., both the LID and AMP-bind domains are almost closed. Because the snapshots between the 35th and 60th iterations fall within a 2.3–2.8 Å RMSD range with these structures, the AMP-bind closing appears to take place (at least partially) in the late stages of the simulation. Although our simulations without the substrate sampled “closed-like” conformations because of the biased dynamics, recent studies (47,48) suggest that the open (ligand-free) AK samples an ensemble of conformations, including those similar to the closed state observed during catalysis.

Our results are in conformity with several studies pointing to the conformational changes and physical order of events during the open-to-closed transition in AK. The plastic network model of Maragakis and Karplus (21) indicated that LID closure precedes the bending motion of the AMP-bind region because of the highly flexible nature of the LID domain and its low elastic energy barrier cost. A coarse-grained approach by Whitford et al. (49), in which structure-based potentials were used, revealed that the free energy barrier of LID domain closure is less than that of the AMP-bind region, implying that AMP-bind closure is the rate-limiting step. An MD study by Lou and Cukier (50) indicated that the LID initially closes toward the core at high temperature.

Table 2 lists independent runs with different DF and MCS parameters: 1), the minimum RMSD attained for each crystal structure; and 2), in parentheses, the specific iteration at which the maximum approach is attained. Independent runs performed using the same parameters (DF = 0.2 and MCS = 1000) provided similar intermediates. Moreover, different MCS (MCS = 100 or 1000) or DFs (DF = 0.1, 0.2, or even 0.5) did not change significantly the minimum RMSD values attained for the x-ray structures. As a result, appropriate simulation parameters should be chosen according to the specifics of each system. Performing long energy minimizations results in more appropriate intermediate structure energies, with the cost of prolonged computational times. However, if the main topic of concern is the exploration of transitional pathways, i.e., the pathway intermediate structures, relatively shorter energy minimizations and/or higher DFs may be used, especially for large biological systems.

TABLE 2.

Closest approaches attained to x-ray structures in different AK runs

| ANM-MC parameters | 1AK2 | 2AK2 | 1DVRB | 1DVRA | 1E4YA | 1E4VA | 2ECKA | 1ANKA | 1AKE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DF = 0.1, MCS = 1000 | 2.88 (30) | 2.81 (30) | 2.52 (40) | 2.30 (40) | 2.35 (100) | 2.32 (100) | 2.30 (100) | 2.30 (100) | 2.29 (105) |

| DF = 0.2, MCS = 100 | 2.91 (15) | 2.82 (15) | 2.50 (20) | 2.11 (25) | 2.36 (45) | 2.32 (50) | 2.34 (55) | 2.27 (55) | 2.27 (50) |

| DF = 0.2, MCS = 1000 (1) | 2.98 (15) | 2.96 (15) | 2.53 (20) | 2.36 (25) | 2.38 (45) | 2.36 (50) | 2.34 (55) | 2.30 (50) | 2.34 (50) |

| DF = 0.2, MCS = 1000 (2) | 2.96 (15) | 2.97 (15) | 2.50 (20) | 2.42 (25) | 2.38 (45) | 2.35 (50) | 2.34 (55) | 2.33 (55) | 2.35 (50) |

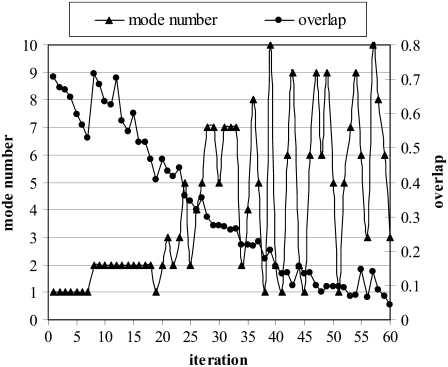

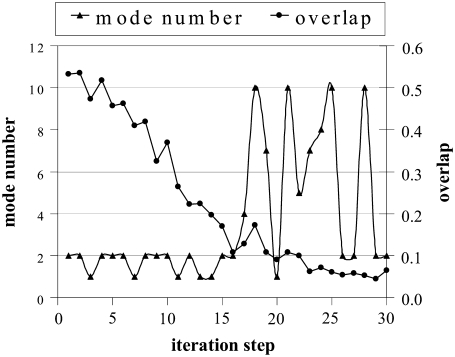

The slow mode with the highest overlap with the target direction, which was chosen as the deformation direction, is depicted in Fig. 5 for each iteration, together with the overlap value (for a run with DF = 0.2, MCS = 1000). Initially, the algorithm chooses the first and then second slowest modes with high overlap values (0.5–0.7), which are associated with LID closing. Up to 20–25 iterations, the conformational change is driven by the lowest-frequency modes, in conformity with previous studies (4,16), and the RMSD to the target structure decreases from 7.13 Å to 4.44 Å. After 20–25 iterations, higher modes associated with the AMP-bind domain enter the picture. These modes, with lower overlap values, provide a more precise mapping of the structure on to target, i.e., final state (down to 2.34 Å RMSD). This outcome is also supported by Patrone and Pande (51), who pointed out the relevance of using higher modes to map a conformational change. They reported that low-frequency modes typically bring the reference conformation ∼50% closer to the target conformation, based on their RMSD, and further approach to the target conformation should be accompanied by higher modes.

FIGURE 5.

Mode directions preferred at each iteration, and corresponding overlap values with target direction obtained during simulation of AK from open to closed states (DF = 0.2, MCS = 1000 cases).

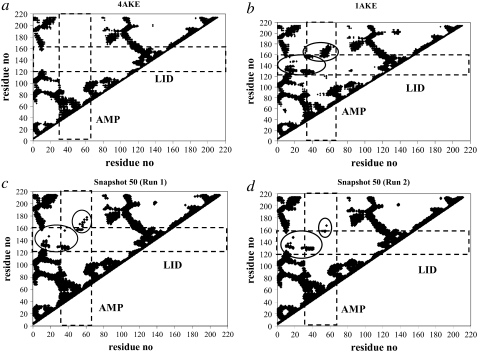

Contact map representations of AK intermediates

In Fig. 6, the Cα atom pairs that are in contact within a cutoff distance of 15 Å are displayed for x-ray structures of open and closed conformers of AK (Fig. 6, a and b) and for the 50th snapshot from two independent simulations with DF = 0.2 Å and MCS = 1000 (Fig. 6, c and d). The contact maps are symmetric, and so only the upper diagonals are presented. The residues belonging to the LID and AMP-bind domains are highlighted within rectangles. The major differences in residue contacts between the open and closed conformers are indicated within black circles in Fig. 6 b. Upon closure, the LID and AMP-bind domains form a close contact with each other and with the core domain. In Fig. 6, c and d, the contact maps of the 50th snapshot, with a maximum approach to the target, are depicted for two different runs. Compared with the contact map of the target structure (Fig. 6 b), it is evident that in both runs, an important part of the necessary contacts indicated by solid circles have been formed. The missing contacts are attributable to the fact that there is still a 2.34-Å RMSD of this snapshot with the target structure.

FIGURE 6.

Contact map representations for open conformer of AK (a), closed conformer of AK (b), and final snapshots of two independent simulations with DF = 0.2 Å and MCS = 1000 (c and d). Only upper diagonals of symmetric map are shown. Data points indicate contacting Cα residues that fall within 15-Å cutoff. Basic differences (circles) between contact maps of open and closed conformers of AK are evident in LID and AMP-bind domains (ranges indicated with rectangles). Contacts generated up to final snapshots of both runs possess close resemblance to contacts present in target form.

The comparative analysis of new contact formation at each snapshot of two independent runs is tabulated in Table 3. Table 3 shows the cumulative percentage of LID-related (first column) and AMP-bind-related (second column) contacts formed at each snapshot, and the overall percentage of common residues (third column) in contact at that particular snapshot across the two runs (both with DF = 0.2 Å and MCS = 1000). The percentages of LID-related and AMP-bind-related contacts are calculated by determining the ratio of the number of contacts present at that snapshot to the corresponding number of contacts found in the target conformation (1AKE). The percentages of contacts belonging to the LID and AMP-bind domains are very similar across the two runs. Both runs confirm the priority of LID-closing, which is then accompanied by AMP-closing. For the final snapshot (50), at most, ∼30% of LID contacts and 10% of AMP-bind contacts that are going to be present in the final closed structure are formed. The overall percentage of common residues is higher, especially at initial levels of the simulation.

TABLE 3.

Comparative analysis of new contact formation at each snapshot across two different runs of AK

| LID contacts (%)

|

AMP-bind contacts (%)

|

Common residues in contact (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Snapshots | Run 1 | Run 2 | Run 1 | Run 2 | |

| 5 | 14.1 | 13.0 | 0 | 0 | 80 |

| 10 | 15.8 | 15.8 | 0 | 0 | 75 |

| 15 | 18.1 | 18.1 | 0 | 0 | 78 |

| 20 | 18.1 | 18.6 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 75 |

| 25 | 18.6 | 22.0 | 1.0 | 1.4 | 69 |

| 30 | 22.6 | 22.6 | 3.1 | 4.1 | 65 |

| 35 | 25.4 | 25.4 | 5.1 | 5.8 | 65 |

| 40 | 26.0 | 26.0 | 6.1 | 6.5 | 60 |

| 45 | 28.2 | 29.4 | 8.5 | 9.9 | 67 |

| 50 | 31.1 | 29.9 | 11.0 | 10.2 | 57 |

In summary, the structure samples some conformations during the relaxation, with possible changes in local contacts that may have an impact on the next ANM moves. Nevertheless, multiple independent runs result in a similar sequence of events (Tables 2 and 3), and MC serves to refine the conformations with the current implementation.

Other test case: hemoglobin

Hemoglobin is another commonly studied example of allosteric transitions in proteins. As an oxygen-binding tetrameric protein, hemoglobin adopts three conformations: a relaxed CO-bound (R2) state (PDB code 1BBB) (52), a relaxed O2-bound (R) state (PDB code 1HHO) (53), and a tense, unliganded (T) state (PDB code 1A3N) (54). Structure R2 was first thought to be an intermediate between T and R, but computational studies suggested that it is instead R, and probably an intermediate between T and R2 (55). Here, we aimed to achieve the T-R2 transition that corresponds to a 3.5 Å RMSD between the two conformers. The RMSDs between the T-R and R-R2 states are 2.4 and 1.8 Å, respectively. Hemoglobin consists of 572 residues in total. In R2, there are two additional valine residues at the beginning of chains B and D, which are discarded here to match the size of the initial and target structures.

RMSD and energy profiles of hemoglobin

Fig. 7 presents the simulation results for hemoglobin, using MCS = 1000. In Fig. 7 a, DFs of 0.1, 0.2, and 0.5 provide close approaches to the target, with stable profiles. Minimum RMSD values to the target (R2) are 1.9 Å with DF = 0.1 and 0.2, and 1.95 Å with DF = 0.5. Fig. 7 b demonstrates the energy values of the snapshots obtained. All three values of DF lead to reasonable RMSD and energy profiles. Indeed, DF = 0.5 Å seems to be a more appropriate choice in this case, because of similar RMSD profiles with DF = 0.1 and 0.2, and closer energy values to the target structure. Moreover, the simulation time is almost half that of the simulation times with DF = 0.1 and 0.2.

FIGURE 7.

(a) RMSD values of human hemoglobin during simulation of transition from T-to-R2 form with previous DFs. (b) Energy profiles of hemoglobin simulations for T-to-R2 transition by different DFs.

Transition pathway of hemoglobin

The RMSD values of snapshots with T, R, and R2 crystal structures are provided in Table 4 for a run performed with DF = 0.2 and MCS = 1000. Srinivasan and Rose (55) suggested that the R state was intermediate between T and R2. In accordance, our intermediate snapshots pass through R on the pathway from T to R2. As the snapshots begin to deviate from the T state, the R state is reached, with a minimum RMSD = 1.89 Å (at the 15th iteration). Subsequently, the R2 state is approached with an RMSD = 1.91 Å (at the 30th iteration). Similar intermediate structures were obtained with DF = 0.5 and MCS = 1000 (Table S1). Thus, for relatively large proteins such as hemoglobin, DF = 0.5 seems more appropriate in terms of computational efficiency, because the RMSD profiles and intermediates are quite similar with the case of lower DFs (DF = 0.1 or 0.2).

TABLE 4.

RMSD values of simulation snapshots with crystal structures of hemoglobin (T, R, and R2 forms) with DF = 0.2 and MCS = 1000

| Snapshots | 1A3N (T) | 1HHO (R)* | 1BBB (R2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | 1.04 | 2.08 | 2.91 |

| 10 | 1.99 | 2.04 | 2.40 |

| 15 | 2.54 | 1.89 | 2.10 |

| 20 | 2.89 | 1.94 | 1.97 |

| 25 | 3.06 | 2.04 | 1.93 |

| 30 | 3.07 | 1.98 | 1.91 |

| 35 | 3.20 | 2.14 | 1.95 |

| 40 | 3.24 | 2.12 | 1.94 |

| 45 | 3.30 | 2.19 | 1.97 |

PDB file (1HHO) includes two monomers. Tetrameric structure was generated using Pymol (56).

Previous studies of hemoglobin transitional pathways reported that the slowest modes successfully brought the T state close to the R and R2 states; however, the backward passages did not prove to be accessible (17,20). These findings are confirmed by our simulation results. A rather important outcome of our simulations is that although the simulation was targeted in the direction of the T-R2 transition, on the path, another state, the R state, was visited first. As a result, the snapshots reveal that R and R2-like structures exist on the hemoglobin transitional pathway.

The directional preferences, i.e., the modes with the highest overlap taken into account during the simulation, are depicted in Fig. 8. In the initial stage (up to the 16th iteration), the first two global modes were selected interchangeably in a random fashion, and guided the major part of the transition. After that point, higher modes with low overlap values (∼0.1) slightly decreased the RMSD from 2.1 to 1.9.

FIGURE 8.

Mode directions preferred, and corresponding overlap values with target direction obtained during simulation of hemoglobin from T to R2 state (DF = 0.2, MCS = 1000 cases).

Targeted Monte Carlo simulation

The TMC simulations were performed to assess the effect of incorporating normal mode directions in the ANM-MC methodology. Similarly, starting with the open conformer of AK, the protein is forced toward the closed conformer by deforming the coordinates along the target direction, without the aid of slow modes. The TMC method reaches the target structure faster with an RMSD ∼0 Å, indicating maximum approach. The energy profiles are very similar to those in the original protocol.

A comparison of TMC snapshots with the intermediate AK-related crystal structures is given in Table 5, which follow a similar trend to that of ANM-MC. However, the RMSDs (2.5–3.4 Å) of the TMC snapshots with the first four crystal structures associated with LID closure (1AK2, 2AK2, 1DVRB, and 1DVRA) are higher than those obtained with ANM-MC (2.3–2.9 Å, in Table 1). In contrast, the TMC approaches more closely the rest of the structures (1E4YA, 1E4VA, 2ECKA, and 1ANKA), which have very similar conformations to the target (RMSD <1 Å).

TABLE 5.

RMSD values between AK-related x-ray structures and intermediate structures obtained with TMC simulations of AK

| Snapshots | 4AKE | 1AK2 | 2AK2 | 1DVRB | 1DVRA | 1E4YA | 1E4VA | 2ECKA | 1ANKA | 1AKE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | 2.20 | 3.68 | 3.55 | 3.92 | 3.80 | 5.52 | 5.82 | 5.91 | 5.81 | 5.83 |

| 10 | 3.26 | 3.43 | 3.22 | 3.09 | 2.95 | 4.24 | 4.51 | 4.62 | 4.55 | 4.53 |

| 15 | 4.44 | 3.53 | 3.43 | 2.70 | 2.55 | 2.99 | 3.24 | 3.33 | 3.26 | 3.25 |

| 20 | 5.62 | 4.14 | 4.06 | 2.88 | 2.74 | 1.84 | 2.00 | 2.04 | 2.02 | 2.01 |

| 25 | 6.80 | 4.99 | 4.94 | 3.52 | 3.40 | 0.96 | 0.83 | 0.95 | 0.81 | 0.81 |

| 30 | 7.55 | 5.59 | 5.56 | 4.08 | 3.96 | 0.96 | 0.28 | 0.33 | 0.48 | 0.15 |

The TMC simulations performed for hemoglobin, starting with the T state, approach the target state R2 with a 0.1-Å approach. Analysis of the simulation trajectory reveals that the intermediate R state is approached by 1.16 Å at the 10th snapshot.

Although most studies in the literature focused on open-to-closed conformational transitions, we also studied the reverse transition in AK by the ANM-MC and TMC methods (detailed results not presented here). The targeted Monte Carlo technique succeeds in generating the reverse (closed-to-open) pathway, with similar pathway intermediates obtained in the forward (open-to-closed) transition simulations. On the other hand, the ANM-MC protocol fails to reach the open conformation because of the low overlap values with the target direction obtained from the start of the simulation. Tama and Sanejouand also showed that reverse transitions from closed-to-open states do not usually correspond to the slow modes obtained from normal mode analysis (16).

In summary, both the ANM-MC and TMC methods proposed here succeed in exhibiting transitions from open-to-closed and free-to-bound forms of AK and hemoglobin, respectively, with reasonable pathway intermediates. The character of the conformational transitions observed in these proteins can be regarded as highly collective. In agreement with previous findings in the literature (57), these types of collective motions can be successfully described by ENM. The TMC method reached the target conformation faster and with a more precise approach. Especially for large systems, this method could be used efficiently. However, the ANM-MC method enabled us to reveal the intermediate conformations (Table 1; first four x-ray structures) more closely in the case of AK, which undergoes a large-scale conformational change. Moreover, in the case of unavailable target information, the TMC method fails to predict and investigate the transitional pathway. In contrast, with additional manipulations over the present ANM-MC algorithm, the TMC method may also be used to simulate such systems with the help of normal modes, and this is the topic of our ongoing research.

Computational efficiency

Besides its simplicity, the ANM-MC algorithm requires reasonably short CPU times for completion. For instance, a single iteration for AK (214 residues), which includes the calculation of the 10 slowest modes by ANM, followed by an energy minimization of MCS = 100 (MCS = 1000) and an RMSD check, takes ∼1 min and 17 s (6 min and 10 s) on a 1.5-GHz Itanium2 processor with 2 GB RAM. A complete run of 48 iterations that drives AK from the open to closed conformation lasts ∼1 h (5 h) for MCS = 100 (MCS = 1000) and DF = 0.2 Å. In the case of hemoglobin (572 residues), a complete run with DF = 0.2 lasts ∼5 days with MCS = 1000, and <1 day with MCS = 100, providing similar intermediates. Thus, a rough comparison of CPU times necessary to simulate such conformational transitions with targeted MD and our ANM-MC or TMC methods indicates that the latter is much more efficient, requiring a couple of days, whereas the former may take on weeks or months, depending on the system size and simulation parameters.

CONCLUSIONS

In this study, the elastic network model ANM is coupled with an MC algorithm that uses knowledge-based potentials of proteins, and the resulting ANM-MC algorithm proves to be useful in the investigation of protein conformational transition pathways. Our method improves upon ANM as well as MC in the sense of providing information about the sequence of events, as well as a more efficient conformational search. Our approach is different from previous NMA-based approaches in two respects: 1), the normal modes and target direction are updated at each iteration; and 2), subsequent energy minimization is performed using MC simulation.

Parameter optimization showed that smaller-sized DFs proved successful in maintaining satisfactory RMSD and energy profiles, achieving a close approach to the target state with reasonable pathway intermediates. However, for faster sampling of transitional pathways in larger systems such as hemoglobin, one may choose larger DFs, followed by shorter energy minimizations, if the elucidation of intermediate conformations and the sequence of events is the main concern.

Application of the ANM-MC algorithm proved successful in achieving the transition between the open and closed conformations of AK (E. coli) (minimum RMSD to the target was 2.29 Å). Specific snapshots along the trajectory fell within acceptable RMSD ranges, with the crystal structures proposed as intermediates on the AK pathway (21). The closing of the LID domain preceded that of the AMP-bind domain, which was also validated with contact map representations. Similarly, the method accomplished the transition from the T to R2 states of hemoglobin (closest approach, 1.9 Å), passing through the R state that was proposed to be an intermediate state between T and R2 (53). Both applications (AK and hemoglobin) revealed that the two lowest-frequency modes were foremost in driving conformational changes. Nevertheless, higher modes were needed at later stages for closer mapping toward the target structure.

The TMC simulations tested the relevance of using normal modes within the present methodology. As expected, it was possible to reach the target almost exactly, using TMC. For most purposes, TMC may provide results as satisfactory as those with ANM-MC. However, in the case of AK, the transition intermediates signifying LID closure were approached more closely with the ANM-MC method. In this respect, an improved technique could involve a combination of ANM-MC and TMC methods. Initially, ANM-MC could be used and after RMSD values leveled off, and TMC would be applied to provide closer mapping to the target state and the intermediates that lie close to the target.

Both ANM-MC and TMC succeeded in exploring the transitional pathways of proteins with multiple conformations, and in proposing pathway intermediate structures in systems of known initial and end states. However, our preliminary studies of systems with unknown target information showed that using normal modes together with pathway energies would be essential when analyzing transitional pathways in such systems.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Bogazici University Fund (Projects 08A50D and 08A507), the Turkish State Planning Organization Project (03K120250), the Tubitak Projects (104M247 and 106M077), the Betil Fund, and EU-FP6-ACC-2004-SSA-2 contract No. 517991.

Editor: Ron Elber.

References

- 1.Kim, M. K., R. L. Jernigan, and G. S. Chirikjian. 2002. Efficient generation of feasible pathways for protein conformation transitions. Biophys. J. 83:1620–1630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lei, M., M. I. Zavodszky, L. A. Kuhn, and M. F. Thope. 2004. Sampling protein conformations and pathways. J. Comput. Chem. 25:1133–1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bahar, I., and A. J. Rader. 2005. Coarse-grained normal mode analysis in structural biology. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 15:586–592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ma, J. 2005. Usefulness and limitations of normal mode analysis in modeling dynamics of biomolecular complexes. Structure. 13:373–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brooks, B., and M. Karplus. 1983. Harmonic dynamics of proteins: normal modes and fluctuations in bovine pancreatic trypsin inhibitor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 80:6571–6575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schlitter, J., M. Engels, P. Kruger, and E. Jacoby. 1993. Targeted molecular dynamics simulation of conformational change-application to T-R transition in insulin. Mol. Simul. 10:291–308. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kong, Y., J. Ma, M. Karplus, and W. N. Lipscomb. 2006. The allosteric mechanism of yeast chorismate mutase: a dynamic analysis. J. Mol. Biol. 356:237–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van der Vaart A., and M. Karplus. 2005. Simulation of conformational transitions by the restricted perturbation-targeted molecular dynamics method. J. Chem. Phys. 122:114903 (1–6). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van der Vaart A., and M. Karplus. 2007. Minimum free energy pathways and free energy profiles of conformational transitions based on atomistic molecular dynamics simulations. J. Chem. Phys. 126:164106 (1–17). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bahar, I., A. R. Atilgan, and B. Erman. 1997. a. Direct evaluation of thermal fluctuations in proteins using a single parameter harmonic potential. Fold. Des. 2:173–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bahar, I., A. R. Atilgan, M. C. Demirel, and B. Erman. 1998. Vibrational dynamics of folded proteins: significance of slow and fast motions in relation to function and stability. Phys. Rev. Lett. 80:2733–2736. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bahar, I. 1999. Dynamics of proteins and biomolecular complexes. Rev. Chem. Eng. 15:319–347. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haliloglu, T., I. Bahar, and B. Erman. 1997. Gaussian dynamics of folded proteins. Phys. Rev. Lett. 79:3090–3093. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bahar, I., and R. L. Jernigan. 1998. Vibrational dynamics of transfer RNAs: comparison of the free and synthease bound forms. J. Mol. Biol. 281:871–885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Atilgan, A. R., S. R. Durell, R. L. Jernigan, M. C. Demirel, O. Keskin, and I. Bahar. 2001. Anisotropy of fluctuation dynamics of proteins with an elastic network model. Biophys. J. 80:505–515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tama, F., and Y. H. Sanejouand. 2001. Conformational change of proteins arising from normal mode calculations. Protein Eng. 14:1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mouawad, L., and D. Perahia. 1996. Motions in hemoglobin studied by normal mode analysis and energy minimization: evidence for the existence of tertiary T-like, quaternary R-like intermediate structures. J. Mol. Biol. 258:393–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mouawad, L., D. Perahia, C. H. Robert, and C. Guilbert. 2002. New insights into the allosteric mechanism of human hemoglobin from molecular dynamics simulations. Biophys. J. 82:3224–3245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tama, F., and C. L. Brooks. 2002. The mechanism and pathway of pH induced swelling in cowpea chlorotic mottle virus. J. Mol. Biol. 318:733–747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xu, C., D. Tobi, and I. Bahar. 2003. Allosteric changes in protein structure computed by a simple mechanical model: hemoglobin T↔R2 transition. J. Mol. Biol. 333:153–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maragakis, P., and M. Karplus. 2005. Large amplitude conformational change in proteins explored with a plastic network model: adenylate kinase. J. Mol. Biol. 352:807–822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zheng, W., and B. R. Brooks. 2005. Normal-modes-based prediction of protein conformational changes guided by distance constraints. Biophys. J. 88:3109–3117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zheng, W., and B. R. Brooks. 2006. Modeling protein conformational changes by iterative fitting of distance constraints using reoriented normal modes. Biophys. J. 90:4327–4336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wu, Y., X. Tian, M. Lu, M. Chen, Q. Wang, and J. Ma. 2005. Folding of small helical proteins assisted by small-angle x-ray scattering profiles. Structure. 13:1587–1597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang, Z., Y. Shi, and H. Liu. 2003. Molecular dynamics simulations of peptides and proteins with amplified collective motions. Biophys. J. 84:3583–3593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.He, J., Z. Zhang, Y. Shi, and H. Liu. 2003. Efficiently explore the energy landscape of proteins in molecular dynamics simulations by amplifying collective motions. J. Chem. Phys. 119:4005–4017. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim, M. K., R. L. Jernigan, and G. S. Chirikjian. 2005. Rigid-cluster models of conformational transitions in macromolecular machines and assemblies. Biophys. J. 89:43–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Haliloglu, T., and I. Bahar. 1998. Coarse-grained simulations of conformational dynamics of proteins: application to apomyoglobin. Proteins. 31:271–281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Haliloglu, T. 1999. Coarse-grained simulations of the conformational dynamics of proteins. Comput. Theor. Polym. Sci. 9:255–260. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kurt, N., and T. Haliloglu. 1999. Conformational dynamics of chymotrypsin inhibitor 2 by coarse-grained simulations. Proteins. 37:454–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Doruker, P., R. L. Jernigan, and I. Bahar. 2002. Dynamics of large proteins through hierarchical levels of coarse-grained structures. J. Comput. Chem. 23:119–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Flory, P. J. 1969. Statistical Mechanics of Chain Molecules. Interscience, New York.

- 33.Bahar, I., and R. L. Jernigan. 1997. Inter-residue potentials in globular proteins and the dominance of highly specific hydrophilic interactions at close separation. J. Mol. Biol. 1:195–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bahar, I., M. Kaplan, and R. L. Jernigan. 1997. b. Short-range conformational energies, secondary structure propensities, and recognition of correct sequence-structure matches. Proteins. 29:292–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grimes, R. G., J. G. Lewis, and H. D. Simon. 1994. A shifted block Lanczos algorithm for solving sparse sysmetric eigenvalues problems. SIAM J. Matrix Anal. Appl. 15:228–272. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marques, O. A. 1995. BLZPACK: Description and User's Guide. Technical Report TR/PA/95/30. CERFACS, Toulouse, France.

- 37.Marques, O. A. 2001. BLZPACK: User's Guide. NERSC, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Berkeley, CA. Available at: http://crd.lbl.gov/∼osni/marques.html#BLZPACK.

- 38.Krebs, W. G., and M. Gerstein. 2000. The morph server: the standardized system for analyzing and visualizing macromolecular motions in a database framework. Nucleic Acids Res. 28:1665–1675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Berry, M. B., B. Maedor, T. Bilderback, P. Liang, M. Glaser, and G. N. Phillips. 1994. The closed conformation of a highly flexible protein: the structure of the E. coli adenylate kinase with bound AMP and AMPPNP. Proteins. 19:183–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Müller, C. W., and G. E. Shulz. 1992. Structure of the complex between adenylate kinase from Escherichia coli and the inhibitor Ap5A refined at 1.9 Å resolution. A model for a catalytic transition state. J. Mol. Biol. 224:159–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Müller, C. W., G. J. Schlauderer, J. Reinstein, and G. E. Shulz. 1996. Adenylate kinase motions during catalysis: an energetic counterweight balancing substrate binding. Structure. 4:147–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Emekli, U., D. Schneidman-Duhovny, H. J. Wolfson, R. Nussinov, and T. Haliloglu. 2007. HingeProt: automated prediction of hinges in protein structures. Proteins. 70:1219–1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schlauderer, G., and G. Schulz. 1996. The structure of bovine mitochondrial adenylate kinase: comparison with isoenzymes in other compartments. Protein Sci. 5:434–441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schlauderer, G., K. Proba, and G. Schulz. 1996. Structure of a mutant adenylate kinase ligated with an ATP-analogue showing domain closure over ATP. J. Mol. Biol. 256:223–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Muller, C. W., and G. Schulz. 1993. Crystal structures of two mutants of adenylate kinase from Escherichia coli that modify the gly-loop. Proteins Struct. Funct. Genet. 15:42–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Berry, M. B., E. Y. Bae, T. R. Bilderback, M. Glaser, and G. N. Phillips. 2006. Crystal structure of ADP/AMP complex of Escherichia coli adenylate kinase. Proteins. 62:555–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Henzler-Wildman, K. A., V. Thai, M. Lei, M. Ott, M. Wolf-Watz, T. Fenn, E. Pozharski, M. A. Wilson, G. A. Petsko, M. Karplus, C. G. Hübner, and D. Kern. 2007. Intrinsic motions along an enzymatic reaction trajectory. Nature. 450:838–844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Arora, K., and C. L. Brooks III. 2007. Large-scale allosteric conformational transitions of adenylate kinase appear to involve a population-shift mechanism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 104:18496–18501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Whitford, P. C., O. Miyashita, Y. Levy, and J. N. Onuchic. 2007. Conformational transitions of adenylate kinase: switching by cracking. J. Mol. Biol. 366:1661–1671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lou, H., and R. I. Cukier. 2006. Molecular dynamics of apo-adenylate kinase: a principal component analysis. J. Phys. Chem. B. 110:12796–12808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Patrone, P., and V. S. Pande. 2006. Can conformational change be described by only a few normal modes? Biophys. J. 90:1583–1593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Silva, M. M., P. H. Rogers, and A. Arnone. 1992. A third quaternary structure of human hemoglobin A at 1.7 Å resolution. J. Biol. Chem. 267:17248–17256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shaanan, B. 1983. Structure of human oxyhemoglobin at 2.1 angstroms. J. Mol. Biol. 171:31–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tame, J. R., and B. Vallone. 2000. The structures of deoxy human hemoglobin and the mutant Hb Tyralpha42His at 120 K. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 56:805–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Srinivasan, R., and G. D. Rose. 1994. The T-to-R transformation in hemoglobin: a reevaluation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 91:11113–11117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.DeLano Scientific LLC, San Carlos, CA. Available at: http://www.pymol.org.

- 57.Yang, L., G. Song, and R. L. Jernigan. 2007. How well can we understand large-scale protein motions using normal modes of elastic network models? Biophys. J. 93:920–929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]