Abstract

Interactions of cationic antimicrobial peptides with living bacterial and mammalian cells are little understood, although model membranes have been used extensively to elucidate how peptides permeabilize membranes. In this study, the interaction of F5W-magainin 2 (GIGKWLHSAKKFGKAFVGEIMNS), an equipotent analogue of magainin 2 isolated from the African clawed frog Xenopus laevis, with unfixed Bacillus megaterium and Chinese hamster ovary (CHO)-K1 cells was investigated, using confocal laser scanning microscopy. A small amount of tetramethylrhodamine-labeled F5W-magainin 2 was incorporated into the unlabeled peptide for imaging. The influx of fluorescent markers of various sizes into the cytosol revealed that magainin 2 permeabilized bacterial and mammalian membranes in significantly different ways. The peptide formed pores with a diameter of ∼2.8 nm (< 6.6 nm) in B. megaterium, and translocated into the cytosol. In contrast, the peptide significantly perturbed the membrane of CHO-K1 cells, permitting the entry of a large molecule (diameter, >23 nm) into the cytosol, accompanied by membrane budding and lipid flip-flop, mainly accumulating in mitochondria and nuclei. Adenosine triphosphate and negatively charged glycosaminoglycans were little involved in the magainin-induced permeabilization of membranes in CHO-K1 cells. Furthermore, the susceptibility of CHO-K1 cells to magainin was found to be similar to that of erythrocytes. Thus, the distinct membrane-permeabilizing processes of magainin 2 in bacterial and mammalian cells were, to the best of our knowledge, visualized and characterized in detail for the first time.

INTRODUCTION

Antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) are short cationic peptides with an amphiphilic nature. They play an important role in the innate immunity of host organisms, including animals, plants, and humans (1). The AMPs are promising candidates for novel anti-infective drugs (2) because they are effective against antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Because early studies suggested that many AMPs target membranes (3–5), the molecular mechanism of membrane permeabilization has been studied extensively, using mainly model membranes. For example, magainin 2 (GIGKFLHSAKKFGKAFVGEIMNS), an α-helical peptide isolated from the African clawed frog Xenopus laevis (6), was suggested to form a toroidal pore with a diameter of 2–3 nm, inducing lipid flip-flop and the translocation of peptides into the inner leaflet of the bilayer coupled to membrane permeabilization (7,8). However, the interactions of AMPs with bacterial membranes are not well-characterized. For instance, membrane potential assays using bacterial cells reveal the kinetics of the permeabilization, but do not give information on pore size, which is essential for discriminating between various proposed models of membrane permeabilization. Electron microscopic observations failed to capture the dynamic process of membrane permeabilization.

Regarding interactions of AMPs with mammalian cell membranes, there have been only a few reports (9–12). It is not unreasonable that most research on AMPs has focused on their antibacterial mechanism. However, the cytotoxic effects of AMPs also need to be studied, because they hamper the systemic application of AMPs (2).

We investigated the interaction of F5W-magainin 2 (MG), an equipotent analogue of magainin 2 (13), with membranes of living bacteria and mammalian cells, using confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM). The peptide was doped with a small amount of tetramethylrhodamine-labeled MG (TAMRA-MG) for imaging.

Bacillus megaterium and Chinese hamster ovary (CHO)-K1 cells were selected as bacterial and mammalian cells, respectively. All cells used in this study were unfixed and living, because the fixation process may significantly alter the intracellular distribution of cationic peptides (14). Most previous studies used fixed cells, regardless of whether they were bacterial or mammalian (9–12,15–17).

The influx of soluble fluorescent molecules of various sizes into the cytosol was monitored, to estimate the size of pores formed by MG. In mammalian cells, the effects of the depletion of ATP and the negatively charged glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) on the membrane-permeabilizing activity of MG were also examined. Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled annexin V (AV), which specifically recognizes phosphatidylserine (PS) (18), was used to detect the lipid flip-flop induced by MG. We found that MG permeabilized both bacterial and mammalian membranes. However, the mode of action differed significantly between the two. The peptide formed pores with a diameter of ∼2.8 nm (<6.6 nm) in the membranes of B. megaterium, and was translocated into the cytosol. In contrast, the peptide significantly perturbed the plasma membrane of CHO-K1 cells, permitting the entry of a large molecule (diameter, >23 nm) into the cytosol, accompanied by membrane budding and lipid flip-flop, mainly accumulating in the mitochondria and nuclei. The membrane-permeabilizing activity of MG was not influenced by ATP and GAGs. Furthermore, the susceptibility of CHO-K1 cells to magainin was found to be similar to that of erythrocytes. This study visualized and characterized in detail the distinct membrane-permeabilizing processes of MG in bacterial and mammalian cells for the first time, to the best of our knowledge.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

An α-modification of Eagle's medium was purchased from ICN Biomedicals (Aurora, OH). The FITC-conjugated AV, TAMRA succinimidyl ester, and Alexa Fluor 647 monoclonal antibody labeling kit were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Carbonic anhydrase (CA) and 2-deoxyglucose (DG) were obtained from MP Biomedicals (Irvine, CA) and Wako Pure Chemicals (Osaka, Japan), respectively. Calcein and 3′,6′-di(O-acetyl)-4′,5′-bis [N,N-bis(carboxymethyl)aminomethyl] fluorescein, tetraacetoxymethyl ester (calcein-AM) were purchased from Dojindo Laboratories (Kumamoto, Japan). The 4-kDa FITC-dextran, 20-kDa FITC-dextran, Mitotracker Green FM, and antimycin A were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). All other chemicals were obtained from Nacalai Tesque (Kyoto, Japan). The synthesis of MG and labeling of N-terminal free peptides with TAMRA were performed according to a standard 9-fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl-based solid-phase method (single peak by high-performance liquid chromatography). The CA was labeled using an Alexa Fluor 647 labeling kit, according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Cell culture

B. megaterium NBRC 13498 cells were cultured in 200 mL of medium (10 g/L polypepton, 2 g/L yeast extract, and 1 g/L MGSO4 · 7H2O) at 30°C. After a 20-h incubation, the culture was collected by centrifugation (4°C, 3000 rpm, 10 min), and washed once with buffer (5 mM HEPES, 100 mM KCl, and 20 mM glucose, pH 7.4). The cells (OD600 = 0.2) were then cultured onto a poly-d-lysine-coated, glass-bottomed 35-mm dish.

The CHO-K1 cells, CHO pgsA-745 lacking GAGs, and pgsD-677 lacking heparan sulfate were cultured in the α-modification of Eagle's medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 units/mL penicillin, and 0.1 mg/mL streptomycin at 37°C with 5% CO2. After being plated onto a glass-bottomed 35-mm dish (100,000 cells) for CLSM and onto a 96-well microplate (10,000 cells) for the calcein-leakage assay, cells were incubated for 20 h at 37°C with 5% CO2. The medium was removed, and cells were resuspended with annexin-binding buffer (10 mM HEPES, 140 mM NaCl, and 2.5 mM CaCl2, pH 7.4) for CLSM, and phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (8.00 g/L NaCl, 0.20 g/L KCl, 1.15 g/L Na2HPO4, and 0.2 g/L KH2PO4, pH 7.4) for the calcein-leakage assay.

Visualization of membrane permeabilization

Soluble fluorescent molecules (calcein, 4.4 kDa FITC-dextran, or 20 kDa FITC-dextran, 40 kDa FITC-dextran, 70 kDa FITC-dextran, and 250 kDa FITC-dextran) were added to B. megaterium or CHO-K1 cells in a glass-bottomed dish at final concentrations of 2 μM, 0.16 mg/mL, 0.32 mg/mL, 0.16 mg/mL, 0.16 mg/mL, and 0.16 mg/mL, respectively. Small aliquots of peptides (8.7 μL) were added directly into the dish at a final concentration of 10 μM (9.8 μM MG and 0.2 μM TAMRA-MG). No cell that permitted the influx of fluorescent molecules was found among cells to which TAMRA-MG did not bind, and TAMRA-MG alone (0.2 μM) did not induce significant binding or permeabilization, indicating that TAMRA-MG and MG have similar membrane-permeabilizing activity. Indeed, TAMRA-MG exhibited membrane-permeabilizing activity comparable to that of the parent peptide (Supplementary Material, Data S1). Confocal images were taken using a Zeiss LSM 510 (Oberkochen, Germany) or a Nikon C1 (Tokyo, Japan) confocal laser scanning microscope. The percentage of influx was calculated from fluorescent intensity (FI), according to the following equation, by examining 20–60 cells:

|

The FI at 3 and 5 min after the addition of peptide solution was chosen for bacterial and the mammalian cells, respectively, because FI almost reached a plateau.

Colocalization of MG and mitochondria-specific marker in CHO-K1 cells

After being plated onto a glass-bottomed 35-mm dish (100,000 cells) for CLSM, cells were incubated for 20 h at 37°C with 5% CO2. The medium was removed, and cells were resuspended with PBS (0.1% dimethylsulfoxide) containing 80 nM Mitotracker Green FM. After a 30-min incubation with 5% CO2, small aliquots of peptides (10 μL) were added directly into the dish at a final concentration of 10 μM (9.8 μM MG and 0.2 μM TAMRA-MG), and observed using CLSM.

Calcein-leakage assay

After cells in a 96-well microplate were washed three times with PBS, resuspended with 2 μM calcein-AM in PBS (0.2% dimethylsulfoxide) or vehicle, and incubated for 1 h to allow calcein-AM to produce fluorescent calcein in the cytosol, free calcein-AM and calcein were removed by washing with PBS. The peptide solution (10 μM MG in PBS) or PBS was added to the cells, followed by incubation for 1 h. Each well was washed three times, and cells were resuspended with 120 μL of PBS/Triton-X (5:1, v/v). Aliquots (100 μL) of the sample were taken into a quartz cell containing 2 mL of PBS. Fluorescence intensity was measured on a Shimadzu RF-5300 spectrofluorometer (Kyoto, Japan) at an excitation wavelength of 490 nm and at an emission wavelength of 515 nm. The percentage of calcein content was calculated as

|

where subscripts c and v refer to calcein-AM-treated and vehicle-treated cells, respectively. Subscripts p and b denote peptide-treated and buffer-treated cells, respectively. Antimycin A (50 nM) and DG (50 mM) were used for ATP depletion (19). Calcein-loaded cells were incubated with the reagents for 30 min before the addition of peptide solution containing the same amount of inhibitors.

Lipid flip-flop in CHO cells

Small aliquots of peptides (8.7 μL) were added directly into the dish at a final concentration of 10 μM (9.8 μM MG and 0.2 μM TAMRA-MG). After a 15-min incubation, cells were washed three times with the annexin-binding buffer to close pores, and prevent AV from recognizing PS in the inner leaflet of the cell membrane. Cells were resuspended in 1 mL of annexin-binding buffer containing Alexa 647-labeled CA (the concentration was adjusted at 0.6 μM of Alexa Fluor 647) and 50 μL of FITC-AV, and observed using CLSM.

Hemolysis

Human erythrocytes (blood type A) from a healthy 23-year-old man were prepared before the experiment. The blood was centrifuged (800 × g, 10 min) and washed three times with PBS to remove the plasma and buffy coat. After resuspension with PBS containing calcein (2 μM), the cells (6.3 × 105 cells/mL) were applied onto a poly-d-lysine-coated, glass-bottomed 35-mm dish. After 2 h, small aliquots of peptides (10 μL) were added directly into the dish at a final concentration of 10 μM (9.8 μM MG and 0.2 μM TAMRA-MG), and observed using CLSM.

RESULTS

Permeabilization of bacterial membranes by MG

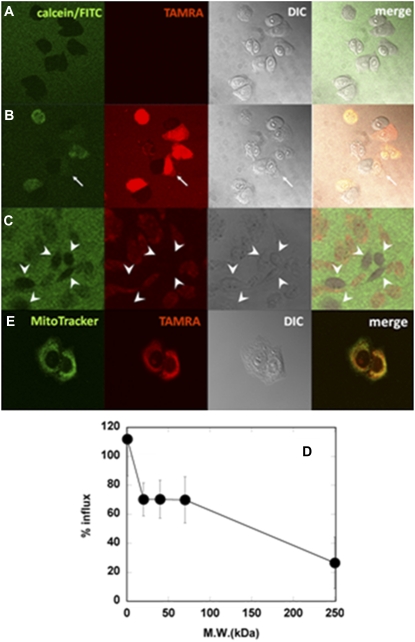

Pores formed by MG in membranes of B. megaterium were visualized using the influx of soluble fluorescent markers of various sizes (Fig. 1). In the absence of peptide, calcein (diameter, ∼1 nm) did not permeate into the cytosol (Fig. 1 A). Aliquots of MG solution, doped with a small amount of TAMRA-MG (2%), were added into the dish at a final peptide concentration of 10 μM, which was larger than the minimal inhibitory concentration under the same conditions (2.5 μM). The MG bound to bacteria, induced the influx of calcein (MW, 623; diameter, ∼1 nm) into the cytosol within seconds, and internalized simultaneously (Fig. 1 B, Movie S1). We also used larger fluorescent molecules to estimate pore size. The 4-kDa FITC-dextran entered the cytosol less efficiently than calcein (Fig. 1 C). Cells were still distinguishable from the background even after the addition of peptide. The rate of influx, calculated as based on FI, was ∼60% (Fig. 1 F). Therefore, the average size of pores was estimated at ∼2.8 nm. The possibility that 4-kDa FITC-dextran could not pass through the peptidoglycan layers was excluded, because the proline-introduced MG analogue peptide A9P-MG (GIGKWLHSPKKFGKAFVGEIMNS) induced a rapid influx of 4-kDa FITC-dextran (Fig. 1 E). The 20-kDa FITC-dextran (diameter, ∼6.6 nm) did not permeate the cell membrane at all (Fig. 1 D), suggesting that the pores are smaller than 6.6 nm. When the cell membrane was permeabilized with the detergent Triton X-100, even 250-kDa FITC-dextran was internalized (Fig. 1 G).

FIGURE 1.

Permeabilization of membranes by MG in B. megaterium. Cells in calcein solution before (A) and 68–70 s after (B) addition of MG/TAMRA-MG at a final concentration of 10 μM (9.8/0.2 μM). Cells in 4.4-kDa FITC-dextran solution (C) and 20-kDa FITC-dextran solution (D) 68–70 s after addition of MG/TAMRA-MG at a final concentration of 10 μM (9.8/0.2 μM). (E) Cells in 4.4-kDa FITC-dextran solution 68–70 s after addition of A9P-MG/TAMRA-A9P-MG at a final concentration of 10 μM (9.8/0.2 μM). From left to right: Calcein/FITC, TAMRA, differential interference contrast (DIC), and merged images. All images were taken at a magnification of 63× at 25°C. (F) Percentages of influx of fluorescent markers 3 min after addition of MG/TAMRA-MG (9.8/0.2 μM) are plotted as a function of molecular mass of the marker. (G) Cells in 250-kDa FITC-dextran solution after addition of Triton X-100 at a final concentration of 0.4 w/v %.

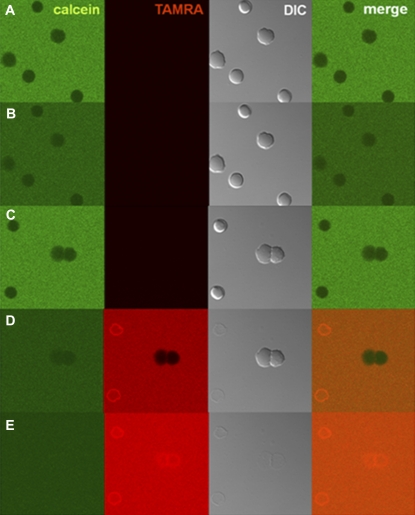

Permeabilization of mammalian membranes by MG

The permeabilization of plasma membranes of CHO-K1 cells by MG was also examined, based on the influx of fluorescent molecules (Fig. 2). Before the addition of peptide, calcein was excluded from the cells (Fig. 2 A). The MG doped with 2% TAMRA-MG also induced the influx of calcein through mammalian membranes (Fig. 2 B, Movie S2). The MG induced membrane budding during the process of membrane permeabilization (Fig. 2 B, arrow). In contrast to bacteria, ∼70% of 20–70-kDa FITC-dextrans and even 30% of 250-kDa FITC-dextran (diameter, ∼23 nm) entered the cytosol through the deformed membranes (Fig. 2, C and D). The peptide-unbound cells indicated by arrowheads in Fig. 2 C were much more distinguishable from the background than the MG-bound cells. The MG peptide itself also entered the cytosol (Fig. 2, B and C, Movie S2). To determine the intracellular localization of the peptide, cells labeled with the mitochondria marker Mitotracker Green FM were treated with the TAMRA-labeled peptide (Fig. 2 E). The peptide was colocalized with the mitochondria marker. The TAMRA fluorescence was also observed in nuclei. Thus, the internalized peptide mainly accumulated in mitochondria and nuclei.

FIGURE 2.

Permeabilization of membranes by MG in CHO-K1 cells. Cells (105 cells/mL, 63×) in calcein solution before (A) and 68–70 s after (B) addition of MG/TAMRA-MG at a final concentration of 10 μM (9.8/0.2 μM). (B) Arrow indicates membrane budding. (C) Cells in 250-kDa FITC-dextran solution 68–70 s after addition of MG/TAMRA-MG at same concentration. Image was magnified 3.5× from 20×. Arrowheads indicate peptide-unbound cells. From left to right: Calcein/FITC, TAMRA, DIC, and merged images. All images were taken at 25°C. (D) Percentages of influx of fluorescent markers 5 min after addition of MG/TAMRA-MG (9.8/0.2 μM). (E) Cells with MitoTracker Green FM staining 70 s after addition of MG/TAMRA-MG at a final concentration of 10 μM (9.8/0.2 μM). From left to right: MitoTracker, TAMRA, DIC, and merged images.

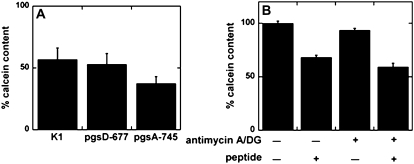

Effects of GAGs and ATP depletion on membrane-permeabilizing activity of MG

The effects of negatively charged extracellular matrix components on the membrane-permeabilizing activity of MG in mammalian cells were estimated using calcein-entrapped CHO-K1 cells and mutant cells. The CHO pgsD-677 lacks the negatively charged glycosaminoglycan heparan sulfate, which was suggested to be important for the internalization of cell-penetrating peptides (20). The CHO pgsA-745 lacks all GAGs. The MG induced almost the same extent of calcein leakage in CHO-K1 cells and its mutants (Fig. 3 A), indicating that GAGs are not involved in permeabilization by MG.

FIGURE 3.

Effects of GAGs and ATP depletion on membrane-permeabilizing activity of MG. (A) Effects of GAGs. Calcein-entrapped cells (wild-type K1, GAG-lacking pgsA-745, and heparan-sulfate-lacking pgsD-677) were treated with 10 μM MG or buffer for 1 h at 37°C. The percentage of calcein content relative to peptide-untreated cells is shown (mean ± SE, n = 8). There was no significance (p > 0.1). Data are representative of two independent experiments. (B) Effects of ATP depletion. Calcein-entrapped CHO-K1 cells were pretreated with a combination of 50 nM antimycin A and 50 mM DG or vehicle for 30 min, followed by 1-h incubation with 10 μM MG or vehicle in the presence or absence of inhibitors at 37°C. Percentages of calcein content are shown (mean ± SE, n = 10). Values were normalized to both peptide-free and inhibitor-free cells. Data are representative of two independent experiments.

The effects of depletion of ATP on the leakage activity of MG were also examined (Fig. 3 B). A combination of antimycin A and DG was used to deplete ATP. The activity of MG was not influenced by ATP depletion (Fig. 3 B), suggesting that MG permeabilized the membranes via an ATP-independent mechanism.

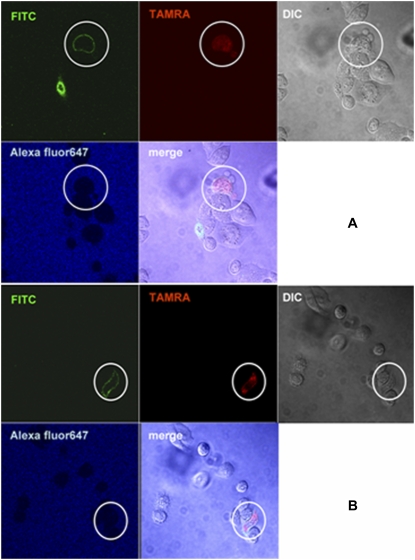

Lipid flip-flop induced by MG in mammalian membranes

We investigated whether MG induces lipid flip-flop in living mammalian membranes, based on the exposure of PS to the cell surface (Fig. 4). The PS is a convenient probe for detecting flip-flop because the lipid normally exists in the inner leaflet of mammalian cell membranes (21). The PS was detected using AV, which selectively binds to it over a certain range of calcium concentrations (18). As described above, the membrane deformation was great enough to permit ∼35-kDa AV into the cytosol to recognize PS in the inner leaflet. The cells were washed three times to recover the barrier function of membranes after a 15-min incubation with the peptide. To confirm the membrane-impermeability of AV, the sample was costained with Alexa 647-labeled CA of a smaller molecular mass (∼30 kDa). Many cells still permitted the entry of CA (data not shown). However, the binding of AV to the cell membrane was observed in CA-impermeable and MG-bound cells (Fig. 4, A and B), indicating that MG induced lipid flip-flop in the living mammalian cell.

FIGURE 4.

Lipid flip-flop induced by MG. CHO-K1 cells were incubated with MG/TAMRA-MG at a final concentration of 10 μM (9.8/0.2 μM) for 15 min, and washed three times to close pores. Cells were stained by FITC-AV and Alexa 647-labeled CA. The image was taken at 25°C. Lipid flip-flop was evident in the encircled cell. (A, B) Two different fields of view are shown.

DISCUSSION

Studies using model membranes proposed several mechanisms to explain the AMP-induced permeabilization of membranes. In the toroidal pore model, suggested for magainin (7,8) and other peptides (22–26), several peptides with surrounding lipid molecules insert into the membrane to form a pore with a defined size, inducing mutually coupled leakage and lipid flip-flop at relatively low peptide/lipid ratios (<1:100). With the carpet mechanism, large amounts of peptides cover membranes like carpets, and eventually disrupt membranes like detergents (27). It should be noted that this mechanism depends not only on peptide species but also on lipid composition. For example, if PS or phosphatidylethanolamine is incorporated into a membrane, magainin disrupts the membrane via a carpet-like mechanism (28). Neutralization of the PS headgroup by positive charges of peptides tends to induce a hexagonal II phase (29). The negative curvature induced by neutralization or by incorporation of phosphatidylethanolamine inhibits the formation of toroidal pores requiring a positive curvature of membranes (7,8), allowing peptides to accumulate on the membrane.

Detailed information on the interaction of AMPs with living cells has been lacking, although several studies used fixed cells (9–12,15–17). Mangoni et al. confirmed the influx of FITC into the cytosol of unfixed Escherichia coli induced by temporin L (30). However, permeability was tested 60 min after the addition of the peptide. There was no information on the process of permeabilization, pore size, or peptide translocation. We characterized the process by which MG permeabilized unfixed biomembranes in detail.

We used Gram-positive B. megaterium as bacterial cells. The absence of outer membranes makes the interpretation of results straightforward. Furthermore, the strain is large, and therefore convenient for microscopic observation, as evidenced in a recent study of nisin (31). Influx experiments were previously conducted using E. coli (30) and giant vesicles (31). However, pore size was not evaluated. We found that the average diameter of pores formed by MG in the plasma membrane of B. megaterium mainly containing negatively charged lipid phosphatidylglycerol (32) was ∼2.8 nm, and certainly smaller than 6.6 nm (Fig. 1 F). The estimated pore size was comparable to that determined in phosphatidylglycerol-containing model membranes. Magainin 2 was proposed to form a toroidal pore with a diameter of 2–3 nm and ∼3.7 nm in a fluorescence-based study (33) and a neutron scattering-based study (34), respectively. These observations suggest that MG permeabilizes bacterial membranes by forming toroidal pores. The detergent-like mechanism can be excluded, because the pores have a finite size. The detergent Triton X-100 allowed the entry of large 250-kDa FITC-dextran (Fig. 1 G). One characteristic of the toroidal pore is the induction of lipid flip-flop (7). However, lipids rapidly move across bilayers via flippases in the membranes of B. megaterium (35). Therefore, it is essentially impossible to discriminate peptide-induced from flippase-induced lipid flip-flop. Similar conclusions were drawn for a chimeric peptide of cecropin and melittin, CM15 (36).

The permeabilization of membranes by MG was also observed in mammalian cells (Fig. 2). However, the mode of action was very different from that in bacterial membranes (Fig. 1). The permeabilization was accompanied by extensive deformation, including membrane budding (Fig. 2 B, Movie S2). Large molecules such as 250-kDa FITC-dextran (diameter, ∼23 nm (37)) entered cells via deformed membranes (Fig. 2 C). Magainin 2 is reported to release lactate dehydrogenase (MW, 140 kDa; diameter, ∼8 nm) from mammalian cells (38,39). The human AMP LL-37 also releases this enzyme from mammalian cells (12) and 40-kDa proteins from Candida albicans (40), suggesting that AMPs can cause massive disruption of membranes. However, the size of lesions depends on the peptide species, because histatin 5, an AMP derived from humans, released ATP but not proteins from C. albicans (40). The sizes of lesions generated by other AMPs in erythrocytes were estimated according to the osmoprotection method: ∼3.0 nm for indolicidin (41), and 3.6–4.0 nm for temporin L (42). Further studies are required to understand what determines the size of pores produced by AMPs.

In the membrane-permeabilizing process of MG (Fig. 2, Movie S2), it is possible that the formation of toroidal pores was inhibited by some positive curvature-counteracting factors, and peptides accumulated on the membrane to disrupt it, similar to the carpet mechanism (27). We suspected cholesterol and sphingomyelin to be such factors because of their tendency to rigidify membranes. Indeed, the incorporation of these lipids inhibits pore formation in PS-based membranes (43). If cholesterol acts to inhibit the formation of pores, its depletion would decrease the size of lesions. However, 250-kDa FITC-dextran entered cholesterol-depleted cells similarly to untreated cells (data not shown). The PS and phosphatidylethanolamine with negative-curvature tendency, mainly in the inner leaflet of cell membranes, could inhibit pore formation when they are exposed to the outer leaflet by MG-induced lipid flip-flop (Fig. 4).

In contrast to its effect on CHO-K1 cells, MG achieves ∼50% hemolysis in erythrocytes only at a much higher concentration, i.e., 1 mM (44). However, a large difference in susceptibility is apparent. In this study, 10 μM of MG were added to 1 × 105 cells/mL, whereas 1 mM was added to 1.2 × 108 cells/mL in the hemolysis assay. Given the radius of the cells, i.e., 10 μm for CHO cells and 4 μm for erythrocytes, we calculated the membrane (monolayer) surface area/peptide values to be 1.3 × 1010 μm2/μmol and 2.4 × 1010 μm2/μmol, respectively. The two values are comparable, indicating the membrane-permeabilizing activity of MG to be similar, because the lipid composition of erythrocytes (45) and CHO cells (46) is not very different. We found that 10 μM of MG were enough to lyse human erythrocytes completely at a lower cell density of 6.3 × 105 cells/mL, corresponding to a surface area/peptide ratio of 1.3 × 1010 μm2/μmol (Fig. 5).

FIGURE 5.

Hemolysis by MG. Erythrocytes in calcein solution before (A) and 70 s after (B) addition of PBS (control). Erythrocytes in calcein solution before (C), and 20 s (D) or 40 s (E) after addition of MG/TAMRA-MG at a final concentration of 10 μM (9.8/0.2 μM). All images were taken at 25°C and magnified 3× from 20×. Cell concentration was 6.3 × 105 cells/mL.

We examined the effects of GAGs on the membrane-permeabilizing activity of MG (Fig. 3 A). The GAGs are known to play a very important role in the interaction between cationic cell-penetrating peptides and cells (20). Similarities and differences between these peptides and AMPs were discussed in a recent review (47). The effects of GAGs on the permeabilization of membranes by MG were almost negligible (Fig. 3 A). Magainin 2 was reported not to bind to heparan sulfate (48). In contrast, LL-37 interacts with GAGs (49). Energy depletion did not influence the membrane-permeabilizing activity of MG (Fig. 3 B), suggesting that MG permeabilized membranes via direct physicochemical peptide-lipid interaction.

Lipid flip-flop induced by MG was observed in CHO-K1 cells (Fig. 4). We used a calcium-containing buffer because AV binds to PS at certain concentrations of calcium (18). Calcium was suggested to induce PS flip-flop by changing the activities of aminophospholipid translocase and phospholipid scramblase (50). Wurth and Zweifach showed, however, that an influx of calcium per se was not sufficient to stimulate PS flip-flop (51). Although the exposure of PS is a hallmark of apoptotic cells, the possibility that MG induced PS flip-flop via the apoptotic pathway can be excluded, because PS flip-flop in apoptotic cells requires several hours (52).

The MG was internalized into the cytosol of B. megaterium (Fig. 1) and CHO-K1 cells (Fig. 2). There are two pathways of internalization: the translocation of pore-constituting peptides upon the disintegration of toroidal pores, as proposed in a liposomal study (7), and the entry of free peptides into the cell through water-filled pores that are larger than the peptide molecule. The internalization of MG into E. coli was previously demonstrated using electron microscopy (53). However, there was no information in that study on the timescale of internalization. Other peptides were also confirmed to be internalized into the cytosol of bacterial (15,17) and mammalian (9–12,16) cells. However, the possibility that the fixation changed the distribution of peptides cannot be excluded (14).

Our previous report showed that MG translocated into the cytosol of HeLa and TM12 cells (9). The translocation was slightly affected by low temperature and sodium azide (9). The inhibitory effect of low temperature is ascribable to an increase in the rigidity of membranes. Membrane-permeabilizing activity was not influenced by ATP depletion with the combination of antimycin A and DG (Fig. 3 B). However, the translocation of MG was reduced by the ATP-depleting agent sodium azide (9). The differences in cell lines and the increased ionic strength using sodium azide might affect the membrane-permeabilizing activity of MG. In addition, the membrane-rigidifying effects of azide, as reported in human bladder carcinoma endothelial cells (54), could also lower the activity of MG, similar to the effects of low temperature. Indeed, ATP-depletion by sodium azide diminished the membrane-permeabilizing activity of histatin 5 against C. albicans by rigidifying membranes via an ATP-depletion-driven polymerization of actin (55).

In this study, the dynamic interaction of MG with living bacterial and mammalian cells was investigated in detail. The peptide appeared to permeabilize cell membranes differently, i.e., by a toroidal mechanism in the former cells, and by the carpet mechanism against the latter. This information adds a valuable contribution to the understanding of AMP-membrane interactions and to the development of effective peptidic antibiotics.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view all of the supplemental files associated with this article, visit www.biophysj.org.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. Kazuhisa Nakayama and the Nikon Corporation for access to the CLSM system.

This work was supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research 17651125 and 20659005 from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan, and by the 21st Century Center Of Excellence Programs “Knowledge Information Infrastructure for Genome Science” and “Initiatives for Attractive Education in Graduate Schools”.

Editor: Thomas J. McIntosh.

References

- 1.Zasloff, M. 2002. Antimicrobial peptides of multicellular organisms. Nature. 415:389–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hancock, R. E., and H. G. Sahl. 2006. Antimicrobial and host-defense peptides as new anti-infective therapeutic strategies. Nat. Biotechnol. 24:1551–1557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zasloff, M., B. Martin, and H. C. Chen. 1988. Antimicrobial activity of synthetic magainin peptides and several analogues. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 85:910–913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wade, D., A. Boman, B. Wahlin, C. M. Drain, D. Andreu, H. G. Boman, and R. B. Merrifield. 1990. All-D amino acid-containing channel-forming antibiotic peptides. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 87:4761–4765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matsuzaki, K., M. Harada, S. Funakoshi, N. Fujii, and K. Miyajima. 1991. Physicochemical determinants for the interactions of magainins 1 and 2 with acidic lipid bilayers. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1063:162–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zasloff, M. 1987. Magainins, a class of antimicrobial peptides from Xenopus skin: isolation, characterization of two active forms, and partial cDNA sequence of a precursor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 84:5449–5453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Matsuzaki, K. 1998. Magainins as paradigm for the mode of action of pore forming polypeptides. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1376:391–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang, H. W. 2006. Molecular mechanism of antimicrobial peptides: the origin of cooperativity. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1758:1292–1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takeshima, K., A. Chikushi, K. K. Lee, S. Yonehara, and K. Matsuzaki. 2003. Translocation of analogues of the antimicrobial peptides magainin and buforin across human cell membranes. J. Biol. Chem. 278:1310–1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tomasinsig, L., B. Skerlavaj, N. Papo, B. Giabbai, Y. Shai, and M. Zanetti. 2006. Mechanistic and functional studies of the interaction of a proline-rich antimicrobial peptide with mammalian cells. J. Biol. Chem. 281:383–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sadler, K., K. D. Eom, J. L. Yang, Y. Dimitrova, and J. P. Tam. 2002. Translocating proline-rich peptides from the antimicrobial peptide bactenecin 7. Biochemistry. 41:14150–14157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lau, Y. E., A. Rozek, M. G. Scott, D. L. Goosney, D. J. Davidson, and R. E. Hancock. 2005. Interaction and cellular localization of the human host defense peptide LL-37 with lung epithelial cells. Infect. Immun. 73:583–591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matsuzaki, K., O. Murase, H. Tokuda, S. Funakoshi, N. Fujii, and K. Miyajima. 1994. Orientational and aggregational states of magainin 2 in phospholipid bilayers. Biochemistry. 33:3342–3349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lundberg, M., and M. Johansson. 2002. Positively charged DNA-binding proteins cause apparent cell membrane translocation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 291:367–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Song, Y. M., Y. Park, S. S. Lim, S. T. Yang, E. R. Woo, I. S. Park, J. S. Lee, J. I. Kim, K. S. Hahm, Y. Kim, and S. Y. Shin. 2005. Cell selectivity and mechanism of action of antimicrobial model peptides containing peptoid residues. Biochemistry. 44:12094–12106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sandgren, S., A. Wittrup, F. Cheng, M. Jonsson, E. Eklund, S. Busch, and M. Belting. 2004. The human antimicrobial peptide LL-37 transfers extracellular DNA plasmid to the nuclear compartment of mammalian cells via lipid rafts and proteoglycan-dependent endocytosis. J. Biol. Chem. 279:17951–17956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Powers, J. P., M. M. Martin, D. L. Goosney, and R. E. Hancock. 2006. The antimicrobial peptide polyphemusin localizes to the cytoplasm of Escherichia coli following treatment. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:1522–1524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Andree, H. A., C. P. Reutelingsperger, R. Hauptmann, H. C. Hemker, W. T. Hermens, and G. M. Willems. 1990. Binding of vascular anticoagulant alpha (VAC alpha) to planar phospholipid bilayers. J. Biol. Chem. 265:4923–4928. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koenig, J. A., R. Kaur, I. Dodgeon, J. M. Edwardson, and P. P. Humphrey. 1998. Fates of endocytosed somatostatin sst2 receptors and associated agonists. Biochem. J. 336:291–298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Poon, G. M., and J. Gariepy. 2007. Cell-surface proteoglycans as molecular portals for cationic peptide and polymer entry into cells. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 35:788–793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Balasubramanian, K., and A. J. Schroit. 2003. Aminophospholipid asymmetry: a matter of life and death. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 65:701–734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kobayashi, S., A. Chikushi, S. Tougu, Y. Imura, M. Nishida, Y. Yano, and K. Matsuzaki. 2004. Membrane translocation mechanism of the antimicrobial peptide buforin 2. Biochemistry. 43:15610–15616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matsuzaki, K., S. Yoneyama, O. Murase, and K. Miyajima. 1996. Transbilayer transport of ions and lipids coupled with mastoparan X translocation. Biochemistry. 35:8450–8456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Imura, Y., M. Nishida, Y. Ogawa, Y. Takakura, and K. Matsuzaki. 2007. Action mechanism of tachyplesin I and effects of PEGylation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1768:1160–1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang, L., T. A. Harroun, T. M. Weiss, L. Ding, and H. W. Huang. 2001. Barrel-stave model or toroidal model? A case study on melittin pores. Biophys. J. 81:1475–1485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hallock, K. J., D. K. Lee, and A. Ramamoorthy. 2003. MSI-78, an analogue of the magainin antimicrobial peptides, disrupts lipid bilayer structure via positive curvature strain. Biophys. J. 84:3052–3060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shai, Y. 1999. Mechanism of the binding, insertion and destabilization of phospholipid bilayer membranes by alpha-helical antimicrobial and cell non-selective membrane-lytic peptides. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1462:55–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matsuzaki, K., K. Sugishita, N. Ishibe, M. Ueha, S. Nakata, K. Miyajima, and R. M. Epand. 1998. Relationship of membrane curvature to the formation of pores by magainin 2. Biochemistry. 37:11856–11863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.de Kroon, A. I., J. W. Timmermans, J. A. Killian, and B. de Kruijff. 1990. The pH dependence of headgroup and acyl chain structure and dynamics of phosphatidylserine, studied by 2H-NMR. Chem. Phys. Lipids. 54:33–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mangoni, M. L., N. Papo, D. Barra, M. Simmaco, A. Bozzi, A. Di Giulio, and A. C. Rinaldi. 2004. Effects of the antimicrobial peptide temporin L on cell morphology, membrane permeability and viability of Escherichia coli. Biochem. J. 380:859–865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hasper, H. E., N. E. Kramer, J. L. Smith, J. D. Hillman, C. Zachariah, O. P. Kuipers, B. de Kruijff, and E. Breukink. 2006. An alternative bactericidal mechanism of action for lantibiotic peptides that target lipid II. Science. 313:1636–1637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.den Kamp, J. O., W. van Iterson, and L. L. van Deenen. 1967. Studies of the phospholipids and morphology of protoplasts of Bacillus megaterium. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 135:862–884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tachi, T., R. F. Epand, R. M. Epand, and K. Matsuzaki. 2002. Position-dependent hydrophobicity of the antimicrobial magainin peptide affects the mode of peptide-lipid interactions and selective toxicity. Biochemistry. 41:10723–10731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ludtke, S. J., K. He, W. T. Heller, T. A. Harroun, L. Yang, and H. W. Huang. 1996. Membrane pores induced by magainin. Biochemistry. 35:13723–13728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hrafnsdottir, S., J. W. Nichols, and A. K. Menon. 1997. Transbilayer movement of fluorescent phospholipids in Bacillus megaterium membrane vesicles. Biochemistry. 36:4969–4978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sato, H., and J. B. Feix. 2006. Osmoprotection of bacterial cells from toxicity caused by antimicrobial hybrid peptide CM15. Biochemistry. 45:9997–10007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Armstrong, J. K., R. B. Wenby, H. J. Meiselman, and T. C. Fisher. 2004. The hydrodynamic radii of macromolecules and their effect on red blood cell aggregation. Biophys. J. 87:4259–4270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maher, S., and S. McClean. 2006. Investigation of the cytotoxicity of eukaryotic and prokaryotic antimicrobial peptides in intestinal epithelial cells in vitro. Biochem. Pharmacol. 71:1289–1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lehmann, J., M. Retz, S. S. Sidhu, H. Suttmann, M. Sell, F. Paulsen, J. Harder, G. Unteregger, and M. Stockle. 2006. Antitumor activity of the antimicrobial peptide magainin II against bladder cancer cell lines. Eur. Urol. 50:141–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.den Hertog, A. L., J. van Marle, H. A. van Veen, W. Van't Hof, J. G. Bolscher, E. C. Veerman, and A. V. Nieuw Amerongen. 2005. Candidacidal effects of two antimicrobial peptides: histatin 5 causes small membrane defects, but LL-37 causes massive disruption of the cell membrane. Biochem. J. 388:689–695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Subbalakshmi, C., V. Krishnakumar, R. Nagaraj, and N. Sitaram. 1996. Requirements for antibacterial and hemolytic activities in the bovine neutrophil derived 13-residue peptide indolicidin. FEBS Lett. 395:48–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rinaldi, A. C., M. L. Mangoni, A. Rufo, C. Luzi, D. Barra, H. Zhao, P. K. Kinnunen, A. Bozzi, A. Di Giulio, and M. Simmaco. 2002. Temporin L: antimicrobial, haemolytic and cytotoxic activities, and effects on membrane permeabilization in lipid vesicles. Biochem. J. 368:91–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Matsuzaki, K., K. Sugishita, N. Fuji, and K. Miyajima. 1995. Molecular basis for membrane selectivity of an antimicrobial peptide, magainin 2. Biochemistry. 34:3423–3429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Matsuzaki, K., K. Sugishita, M. Harada, N. Fujii, and K. Miyajima. 1997. Interactions of an antimicrobial peptide, magainin 2, with outer and inner membranes of Gram-negative bacteria. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1327:119–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Virtanen, J. A., K. H. Cheng, and P. Somerharju. 1998. Phospholipid composition of the mammalian red cell membrane can be rationalized by a superlattice model. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 95:4964–4969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nagan, N., A. K. Hajra, L. K. Larkins, P. Lazarow, P. E. Purdue, W. B. Rizzo, and R. A. Zoeller. 1998. Isolation of a Chinese hamster fibroblast variant defective in dihydroxyacetonephosphate acyltransferase activity and plasmalogen biosynthesis: use of a novel two-step selection protocol. Biochem. J. 332:273–279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Henriques, S. T., M. N. Melo, and M. A. Castanho. 2006. Cell-penetrating peptides and antimicrobial peptides: how different are they? Biochem. J. 399:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Klocek, G., and J. Seelig. 2008. Melittin interaction with sulfated cell surface sugars. Biochemistry. 47:2841–2849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Baranska-Rybak, W., A. Sonesson, R. Nowicki, and A. Schmidtchen. 2006. Glycosaminoglycans inhibit the antibacterial activity of LL-37 in biological fluids. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 57:260–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bevers, E. M., P. Comfurius, D. W. Dekkers, and R. F. Zwaal. 1999. Lipid translocation across the plasma membrane of mammalian cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1439:317–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wurth, G. A., and A. Zweifach. 2002. Evidence that cytosolic calcium increases are not sufficient to stimulate phospholipid scrambling in human T-lymphocytes. Biochem. J. 362:701–708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Martin, S. J., C. P. Reutelingsperger, A. J. McGahon, J. A. Rader, R. C. van Schie, D. M. LaFace, and D. R. Green. 1995. Early redistribution of plasma membrane phosphatidylserine is a general feature of apoptosis regardless of the initiating stimulus: inhibition by overexpression of Bcl-2 and Abl. J. Exp. Med. 182:1545–1556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Haukland, H. H., H. Ulvatne, K. Sandvik, and L. H. Vorland. 2001. The antimicrobial peptides lactoferricin B and magainin 2 cross over the bacterial cytoplasmic membrane and reside in the cytoplasm. FEBS Lett. 508:389–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Haidekker, M. A., H. Y. Stevens, and J. A. Frangos. 2004. Cell membrane fluidity changes and membrane undulations observed using a laser scattering technique. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 32:531–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Veerman, E. C., M. Valentijn-Benz, K. Nazmi, A. L. Ruissen, E. Walgreen-Weterings, J. van Marle, A. B. Doust, W. van't Hof, J. G. Bolscher, and A. V. Amerongen. 2007. Energy depletion protects Candida albicans against antimicrobial peptides by rigidifying its cell membrane. J. Biol. Chem. 282:18831–18841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.