Abstract

Dementia is a progressive life limiting condition with increasing prevalence and complex needs. Palliative care needs of patients with dementia are often poorly addressed; symptoms such as pain are under treated while these patients are over subjected to burdensome interventions. Research into palliative care in dementia remains limited but recent developments together with national guidelines and policies set foundations for improving the delivery of palliative care to this group of the population.

Dementia is a progressive irreversible clinical syndrome characterised by widespread impairment of mental function which may include memory loss, language impairment, disorientation, personality change, difficulties with activities of daily living, self neglect and psychiatric syndromes.1

The prevalence of dementia increases with age (from 1 in 1000 at age 40–65 years to 1 in 5 over age 80 years) and the median length of survival from diagnosis to death is 8 years.2,3 Furthermore, the number of patients with dementia is estimated to double over the next 50 years.4 Dementia is incurable: about 100 000 people with dementia die each year in the UK.5

These figures will significantly underestimate the number of people requiring palliative care support in the context of dementia. For every patient there will be at least one carer who will face complex and challenging problems as the disease progresses: aggressive behaviour, restlessness and wandering, incontinence, delusions and hallucinations, reduced mobility and feeding problems. There are at least 5.7 million caregivers in the UK.6

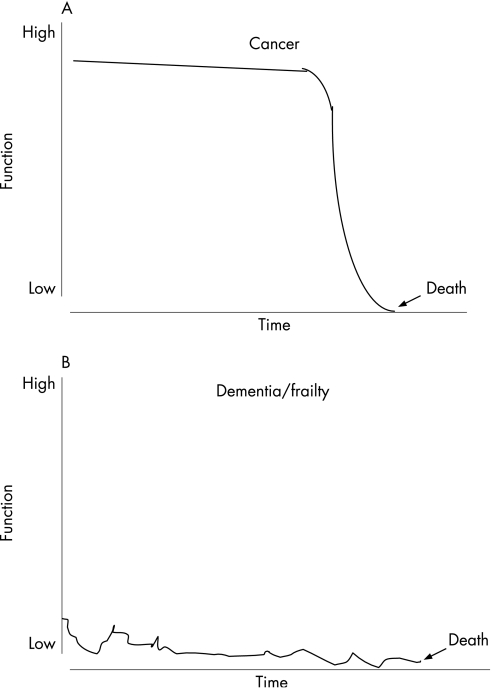

The disease course that dementia usually follows is one of prolonged and progressive disability (fig 1).7,8 The level of baseline function is often low as the disease primarily affects older people who will have already accumulated many other co‐morbidities.7 This is in contrast to cancer which usually follows an initial slow overall decline from a high level of function, followed by a relatively rapid decline in function at the end of life, and a fairly predictable terminal phase where there is time to anticipate palliative care needs and plan for end‐of‐life care.7,9

Figure 1 Disease trajectories in (A) cancer and (B) dementia.7,8

Dementia is therefore associated with complex needs and people with dementia (and their carers) have been shown to have palliative care needs equal to those of cancer patients.5,10 Furthermore, a palliative care approach is favoured by formal and informal carers10 and the current World Health Organization definition of palliative care extends to incorporate non‐malignant life‐limiting disease as:10,11

“…an approach that improves the quality of life of patients and their families facing the problems associated with life threatening illness … by means of early identification and impeccable assessment and treatment of pain and other problems, physical, psychosocial and spiritual”.

PALLIATING DEMENTIA: CURRENT PROBLEMS

Place of death

Despite the wish of the majority of dementia patients (and their families) to die in their own home,2 most will die in hospital in acute wards where staff may be poorly trained or have insufficient time to manage their individual needs, or in care homes where there may be inadequate staff training in palliative care, poor symptom control and lack of psychological and emotional support.1,12

Assessment of pain and other needs

It has been consistently found that pain is under recognised and under treated in dementia patients; impaired communication (particularly difficulties with recall, interpretation of sensations and verbal expression) reduces ability to express pain and for attendants to recognise it.10,13,14,15,16,17,18 Dementia patients are unlikely to have any assessment of spiritual needs before death or documentation of any known religious beliefs.19

Access to specialist palliative care

Patients with dementia compared to those without are less likely to be referred to palliative care teams, prescribed fewer palliative care medications and are infrequently referred or denied access to hospice care.5,19,20,21

Care planning

Patients with dementia are less likely to have advance care planning than those with terminal cancer: advance directives (including withholding tube feeding), “Do not resuscitate” orders, and “Do not hospitalise” instructions.5,12,22 In addition, patients with dementia are more likely to experience uncomfortable or aggressive intervention at the end of life: blood tests, intravenous therapy, arterial blood gases and feeding tubes.12,13,19,22,23

Challenges of older people

Dementia is principally a disease of older people and holistic care of these patients will invariable have to incorporate the challenges of managing older people9,11,24,25:

older people experience multiple problems and disabilities and invariably require more complex packages of treatment and social care

there is a greater risk of adverse drug reactions and iatrogenic illness

older people are also afflicted by the problems associated with ageing itself (for example, problems with bowel and bladder, sight and hearing) which adds further complexity to managing their problems

long term care for seriously ill relatives is unpaid and unsupported work that may damage the health, well‐being and financial security of caregivers themselves

elder abuse (physical, psychological, sexual, financial or neglect) is an important problem but is often not recognised, not recorded and not reported; dementia is consistently identified as a risk factor for elder abuse.

Predicting prognosis

The dementia disease pathway presents a number of challenges: difficulty in estimating prognosis or when somebody is entering the terminal phase, difficulty in appropriate timing of palliative care along a pathway that may last several years, and a significant physical and psychological carer burden from an early stage in the disease course.7,8

Research

A Medline search for “palliative care and dementia” yields 164 references compared with 265 for “palliative care and heart failure” and 9645 for “palliative care and cancer”. A recent systematic review of the evidence for a palliative care approach in advanced dementia concluded that despite the increased interest in palliative care in dementia, there is currently little evidence on which to base such an approach.19

The paucity of evidence may in part be explained by the difficult ethical and practical issues of conducting clinical research with this group of the population (for example, the ethical issues surrounding research where participants are unable to give informed consent).13 Practically, outcome measures are difficult to define: many of the few studies in this area have used “mortality” and found no benefit.13 While improving mortality is not the aim of adopting holistic palliative care, measuring quality of life outcomes in patients unable to communicate is extremely difficult.

PALLIATING DEMENTIA: SOLUTIONS

When to deliver palliative care for dementia patients

The disease trajectory of dementia makes identification of the terminal phase very difficult, but it is often hallmarked by increasingly frequent infections, disability and impairment. Prognostic indicators (table 1) have been developed to help identify patients with dementia and other non‐malignant disease who are likely to be in the last year of life and require palliative and supportive care (although these tools require further validation).18,26

Table 1 Prognostic indicators for dementia27.

| General predictors of end stage illness | Specific prognostic indicators in dementia |

|---|---|

| Multiple comorbidity with no primary diagnosis | Unable to walk without assistance, and |

| Weight loss >10% over 6 months | Urinary and faecal incontinence, and |

| General physical decline | Unable to dress without assistance |

| Serum albumin <25 g/l | Barthel score <3* |

| Reduced performance status/Karnofsky score <50%* | Plus any one of: |

| Dependence in most activities of daily living | – 10% weight loss over 6 months without other cause |

| – pyelonephritis or urinary tract infection | |

| – serum albumin <25 g/l | |

| – “high” Waterlow score for pressure score risk | |

| – recurrent fever | |

| – reduced oral intake/weight loss | |

| – aspiration pneumonia |

*The Karnofsky score and Barthel score measure patient performance on activities of daily living with the Karnofsky score giving a percentage value between 10 and 100 and the Barthel score giving a total score out of 20.

The surprise question “Would you be surprised if this patient were to die in the next 6–12 months” has been suggested as a useful trigger question to help identify patients with non‐malignant disease who are approaching the end of life.26

Identification of this phase is important for a number of reasons: to plan care, to prepare the family and carers for the end of life and make provision for adequate terminal care.

Medication review as part of this process is important to reduce tablet burden and withdraw medication that has become superfluous27—for example, the continued administration/repeat prescribing of a statin and calcium supplement to an end‐stage dementia patient is highly questionable.

Timely support for carers is also important. Dementia imposes a significant burden on carers: mental and physical illness, social isolation and financial difficulties. Support can be provided as respite care, financial support and benefits, providing information (for example, regarding prognosis) and education (particularly regarding issues such as power of attorney and advance directives, manual handling and administration of medication).28

Where to deliver palliative care for dementia patients

It is commonly stated that patients with dementia lack access to palliative care in hospice settings; less than 1% of patients in inpatient hospices have dementia as their primary diagnosis.2

Current hospice provision in the UK would be inadequate to care for these patients in the terminal phase; indeed, it could be argued that moving a patient with severe cognitive impairment to a new unfamiliar environment with unfamiliar staff (with less experience in managing dementia patients) is likely to have a deleterious effect on quality of life and likely to increase agitation, disorientation and distress.

Hospice care may, however, be appropriate for some cases—for example, those individuals requiring complex symptom control or where there is a lack of support available, such as those living alone with no close relative. Access to specialised palliative care should be based on need and not age or diagnosis. However, as many specialised palliative care services are often partially funded by charitable cancer organisations, a review of funding will be needed. Palliative care specialists have expressed the need for their involvement in non‐malignant disease for some time.29

A more practical approach is therefore delivering hospice quality palliative care to dementia patients in their usual place of residence, and there are a number of developing strategies to facilitate this—for example, the Liverpool care pathway for the end of life, and the Gold Standards Framework.

While most older people express a preference to die at home, in reality most will die in hospital or in a nursing home. Nursing and auxiliary staff on hospital wards and in nursing homes often have little specific palliative care training which is clearly an area where resources are needed. Educational and self‐study programmes for care assistants in nursing homes do appear to improve knowledge and attitude regarding end of life care in dementia, and this knowledge appears to be maintained.30

How to deliver palliative care to dementia patients

Guidelines and care pathways

There is evidence that the use and audit of multidisciplinary guidelines improve the palliation of symptoms in dementia patients.31 The Liverpool care pathway for the end of life32 facilitates delivery of holistic palliative care in a variety of settings and it is being widely adopted in hospitals, hospices and in the community. Its use is endorsed by the proposed National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidelines on dementia which includes a section on palliative care issues (table 2).

Table 2 NICE guidelines on dementia: key palliative care components1.

| • Dementia care should incorporate a palliative care approach including the Gold Standards Framework and the Liverpool care pathway for the dying patient. |

| • Advance care planning should be utilised by health and social care professionals, guided by the patient and/or carer where appropriate. |

| • The role of the Mental Capacity Act 2005 for advance decisions to refuse treatment and the Preferred Place of Care documentation are emphasised. |

| • Palliative care services should be available to people with dementia in the same way that they are available to people who do not have dementia. |

| • Artificial feeding, antibiotics for fever and cardiopulmonary resuscitation are generally not appropriate in the terminal stages of dementia. |

| • If people with dementia have unexplained changes in behaviour they should be assessed to see whether they are experiencing pain, potentially by the use of an observational pain assessment tool. |

NICE, National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence.

Equally, the guidelines also endorse the use of the Gold Standards Framework, a programme developed primarily for use in primary care based on the 7 C's: communication, coordination, control of symptoms, continuity, continued learning, carer support, and care of the dying.26 The emphasis on anticipatory care (to reduce crises and inappropriate admissions) and the transfer and communication of information to out‐of‐hours services are particularly important.

Both of these strategies are also recommendations of other key government directives in the UK including the Department of Health Guide to end of life care in care homes (2006) document and the NICE guidance on supportive and palliative care (2004).

Advance care planning emerges as a consistent theme and palliative care plans for hospitalised patients with end stage dementia seem to reduce inappropriate interventions (for example, feeding tubes, phlebotomy and systemic antibiotics),21 particularly as there is no evidence of any beneficial effect for patients with advanced dementia of:

antibiotics for fever (no improvement in survival or comfort)18

artificial feeding (no improvement in nutrition, preventing aspiration pneumonia, functional status or mortality)33

cardiopulmonary resuscitation.1

Pneumonia in patients with advanced dementia is associated with a high mortality, even where routine hospital care is given. Consideration should therefore be given to directing attention to relieving pain and other distressing symptoms and minimising burdensome interventions in this group of patients.34

The implications of the new Mental Health Act should also be mentioned. Current UK law allows an individual to nominate another person to have enduring powers of attorney with regard to the management or property and affairs. However, the new Act which will come into force in April 2007 will allow an individual to nominate another person to also make healthcare decisions on their behalf when they lose the capacity to do so, although this will not extend to refusing life‐sustaining treatment unless this is explicitly stated.35

Symptom management

Patients with dementia may express their pain in ways that are quite different from those of elderly people without dementia; the complexity and consequent inadequacy of pain assessment therefore leads to the under treatment of pain.14 Observational tools have been developed in this context—for example, the Checklist of Nonverbal Pain Indicators uses observers scores of vocalisation, grimaces, bracing, rubbing, restlessness and verbal complaints to detect pain.15,17 The Observational Pain Behaviour Tool, the Pain Assessment in Advanced Dementia Scale, the Pain thermometer, and the Faces Pain Scale are other examples of tools which have been developed, although most of these tools require further validation.16,17 It had been postulated that additional insight could emerge from measuring autonomic responses such as heart rate and blood pressure, but research studies have not found these to be particularly sensitive markers.14

Main points

Dementia is a progressive irreversible clinical syndrome associated with complex needs and high physical and psychological carer burden.

Patients with dementia are less likely to be referred to palliative care teams, are prescribed fewer palliative care medications, often have under treated pain, and are unlikely to have any assessment of spiritual needs before death.

Recent advances in palliative care for dementia include development of prognostic and pain assessment tools, use of the Liverpool care pathway for the end of life, and recognition of the importance of advanced care planning.

There is always difficulty applying tools developed for research purposes for use in clinical practice (for reasons of feasibility, acceptability, etc). Perhaps the key message that is emerging is the importance of careful assessment of people with dementia and behavioural disturbance, pain being one of the most common causes.36

Key references

Davies E, Higginson IJ. Better palliative care for older people. World Health Organization Europe, 2004.

Hughes JC, Robinson L, Volicer L. Specialist palliative care in dementia. BMJ 2005;330:57–8.

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Dementia: supporting people with dementia and their carers (draft guidelines). London: NICE, 2006.

Sachs GA, Shega JW, Cox‐Hayley D. Barriers to excellent end‐of‐life care for patients with dementia. J Gen Intern Med 2004;19:1057–63.

Schreder E, Oosterman J, Swaab D, et al. Recent developments in pain in dementia. BMJ330:461–4.

Research

Growth of the evidence base to guide clinical practice in dementia patients is needed. A systematic review of the evidence for a palliative care approach in dementia found only one randomised controlled trial.13 Clearly more high quality randomised controlled trials and qualitative studies are necessary to determine the most appropriate interventions and most effective methods of delivering palliative care.

The further development and validation of tools by which pain and other symptoms can be better recognised in non‐communicative patients with dementia should be a primary goal of future research.14 Improving the outcome measures used is another developing area; scales such as the Palliative Care Outcome Scale are starting to be validated in the dementia setting to encompass key quality of life outcomes.37 Another unexplored area is that of potential differences in palliative care needs for different subtypes of dementia (Alzheimer's disease, vascular dementia, dementia with Lewy bodies, and fronto‐temporal dementia).

Current palliative care initiatives in the UK such as the NHS End of Life Care Programme (incorporating the Gold Standards Framework, Preferred Place of Care Plan, Liverpool care pathway, etc) will hopefully help direct research interests and opportunities towards the palliative care aspects of dementia.

CONCLUSION

Evidence has accumulated that there are major deficiencies in palliative care for people with dementia: poor symptom management, lack of forward care planning, poor access to specialist palliative care, difficulty in predicting prognosis (all of which are compounded by the challenges of managing disease in older people), and lack of clinical research. There are, however, some significant recent initiatives and developments to try and redress this imbalance. While there is still some way to go in this area (particularly in building an evidence base to inform clinical practice), recent interest and a change in approach to these patients sets foundations for improvement in end of life care for patients with dementia and their carers.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None

References

- 1.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence Dementia: supporting people with dementia and their carers (draft guidelines). London: NICE, 2006

- 2.Davies E, Higginson I J.Better palliative care for older people. World Health Organisation Europe 2004

- 3.Alzheimer's Society www.alzheimers.org.uk (accessed 15 Oct 2006)

- 4.Byrne A, Curran S, Wattis J. Alzheimer's disease. Geriatric Medicine 2006S213–16. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bayer A. Death with dementia‐the need for better care. Age and Ageing 200635101–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Forsyth D, Anderson D, Bullock R.et alDelirious about dementia. Consensus statement. London: British Geriatric Society, 2005

- 7.Murray S A, Kendall M, Boyd K.et al Illness trajectories and palliative care. BMJ 20053301007–1011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murtagh F E M, Preston M, Higginson I. Patterns of dying: palliative care for non‐malignant disease. Clin Med 2004439–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lachs M S, Pillemer K. Elder abuse. Lancet . 2004;3641263–1272. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Hughes J C, Robinson L, Volicer L. Specialist palliative care in dementia. BMJ 200533057–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davies E, Higginson I J.Better palliative care for older people. Denmark: World Health Organization Europe, 2004

- 12.Mitchell S L, Kiely D K, Hamel M B. Dying with advanced dementia in the nursing home. Arch Intern Med 2004164321–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sampson E L, Ritchie C W, Lai R.et al A systematic review of the scientific evidence for the efficacy of a palliative care approach in advanced dementia. Int Psychogeriatr 20051731–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schreder E, Oosterman J, Swaab D.et al Recent developments in pain in dementia. BMJ330461–464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nygaard H A, Jarland M. The checklist of nonverbal pain indicators (CNPI): testing of reliability and validity in Norwegian nursing homes. Age and Ageing 20063579–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Amella E J. Geriatrics and palliative care: collaboration for quality of life until death. Journal of Hospice and Palliative Nursing 2003540–48. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zwakhalen S M G, Hamers J P H, Abu‐Saad H H.et al Pain in elderly people with severe dementia: a systematic review of behavioural pain assessment tools. BMC Geriatrics 2006: 6, 3. http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471‐2318/6/3 (accessed 17 July 2006) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Sachs G A, Shega J W, Cox‐Hayley D. Barriers to excellent end‐of‐life care for patients with dementia. J Gen Intern Med 2004191057–1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sampson E L, Gould V D, Lee D. Difference in care received by patients with and without dementia who died during acute hospital admission: a retrospective cohort study. Age and Ageing 200635187–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shega J W, Levin A, Hougham G W.et al Palliative excellence in Alzheimer care efforts (PEACE): A program description. J Palliat Med 20036315–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ahronheim J C, Morrison R S, Morris J.et al Palliative care in advanced dementia: a randomized controlled trial and descriptive analysis. J Palliat Med 20003265–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mitchell S L, Kiely D K, Hamel M B. Dying with advanced dementia in the nursing home. Arch Intern Med 2004164321–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ahronheim J C, Morrison R S, Baskin S A.et al Treatment of the dying in the acute care hospital. Advanced dementia and metastatic cancer. Arch Intern Med 19961562094–2100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.British Geriatric Society Palliative and end of life care for older people. BGS Compendium Document 4. 8. London: British Geriatric Society, 2004

- 25.National Council for Palliative Care The palliative care needs of older people. Briefing Bulletin 14, January 2005

- 26.Gold Standards Framework http: www.goldstandardsframework.nhs.uk (accessed 17 July 2006)

- 27.Bowman C. Prescribing treatment for neurological disease in care homes. Geriatric Medicine 2006S26–11. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Albinsson L, Strang P. Differences in supporting families of dementia patients and cancer patients: a palliative perspective. Palliat Med 200317359–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McKinley R K, Stokes T, Exley C.et al Care of people dying with malignant and cardiorespiratory disease in general practice. Br J General Practice 200454909–913. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Parks S M, Haines C, Foreman D.et al Evaluation of an educational program for long‐term care nursing assistants. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association 2005661–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lloyd‐Williams M, Payne S. Can multidisciplinary guidelines improve the palliation of symptoms in the terminal phase of dementia? Int J Palliat Nurs 20028370–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ellershaw J, Ward C. Care of the dying patient: the last hours or days of life. BMJ 200332630–34. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cervo F A, Bryan L, Farber S. A review of the evidence for feeding tubes in advanced dementia and the decision‐making process. Geriatrics 20066130–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morrison R S, Siu A L. Survival in end‐stage dementia following acute illness. JAMA 200028447–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sheather J. The Mental Capacity Act 2005. Clinical Ethics 2006133–36. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carr D, Crome P. The management of behavioural problems in dementia. Geriatric Medicine 20063613–18. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brandt H, Deliens L, van der Steen J T.et al The last days of life of nursing home patients with and without dementia assessed with the palliative care outcome scale. Palliat Med 200519334–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]