Abstract

The diagnostic approach to ureteric colic has changed due to the introduction of new radiological imaging such as non‐contrast CT. The role of intravenous urography, which is regarded as the gold standard for the diagnosis of ureteric colic, is being challenged by CT, which has become the first‐line investigation in a number of centres. The management of ureteric colic has also changed. The role of medical treatment has expanded beyond symptomatic control to attempt to target some of the factors in stone retention and thereby improve the likelihood of spontaneous stone expulsion.

Ureteric colic is an important and frequent emergency in medical practice. It is most commonly caused by the obstruction of the urinary tract by calculi. Between 5–12% of the population will have a urinary tract stone during their lifetime, and recurrence rates approach 50%.1

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

The classic presentation of a ureteric colic is acute, colicky flank pain radiating to the groin. The pain is often described as the worst pain the patient has ever had experienced. Ureteric colic occurs as a result of obstruction of the urinary tract by calculi at the narrowest anatomical areas of the ureter: the pelviureteric junction (PUJ), near the pelvic brim at the crossing of the iliac vessels and the narrowest area, the vesicoureteric junction (VUJ). Location of pain may be related but is not an accurate prediction of the position of the stone within the urinary tract. As the stone approaches the vesicoureteric junction, symptoms of bladder irritability may occur.

Calcium stones (calcium oxalate, calcium phosphate and mixed calcium oxalate and phosphate) are the most common type of stone, while up to 20% of cases present with uric acid, cystine and struvite stones.

Physical examination typically shows a patient who is often writhing in distress and pacing about trying to find a comfortable position; this is, in contrast to a patient with peritoneal irritation who remains motionless to minimise discomfort. Tenderness of the costovertebral angle or lower quadrant may be present. Gross or microscopic haematuria occurs in approximately 90% of patients; however, the absence of haematuria does not preclude the presence of stones.

DIAGNOSIS

Besides routine history and clinical examination, investigations of patients with suspected ureteric colic include plain abdominal radiography, ultrasound, intravenous urography and computed tomography.

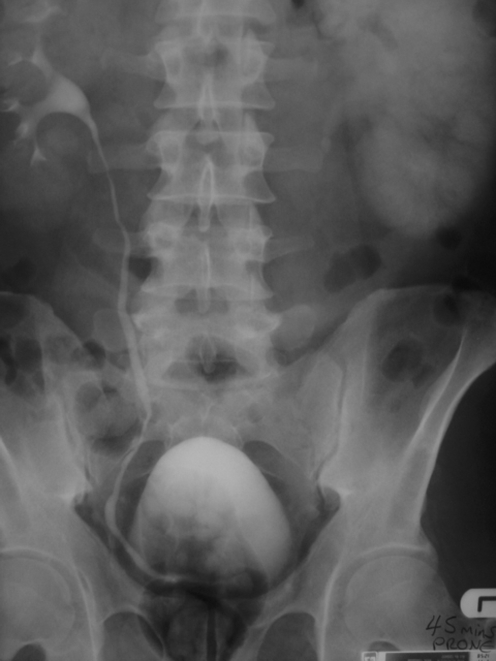

Plain radiograph of the kidney, ureter and bladder

A plain radiograph of the kidney, ureter and bladder (KUB) has a sensitivity that ranges from 45–60% in the evaluation of acute flank pain.2 Overlaying bowel gas or stool (faecoliths) and abdominal or pelvic calcifications (phleboliths) can make identification of ureteric stones difficult. In addition, a KUB cannot visualise radiolucent stones (10–20% of stones), thus limiting the value of plain radiography. However, a KUB may suffice for assessing the size, shape, and location of urinary calculi in some patients (fig 1).

Figure 1 Patient presented with left loin pain. Kidney, ureter and bladder (KUB) x ray showing 7 mm radiopaque stone laying lateral to the tip of transverse process of L2.

Ultrasonography

Ultrasonography allows direct demonstration of urinary stones located at the PUJ, the VUJ, and in the renal pelvis or calyces.3 Stones located between the PUJ and VUJ, however, are extremely difficult to visualise with ultrasonography.

Intravenous urography

Since it was first performed in 1923, intravenous urography (IVU) has been the traditional “gold standard” in the evaluation in ureteric colic. It provides structural and functional information, including site, degree and nature of obstruction. Whereas IVU has a detection rate as high as 70–90% (fig 2),4 it can only visualise radiopaque stones (80–90% of stones). Despite its usefulness, there are some undesirable aspects of IVU, including radiation exposure, risk of nephrotoxicity, contrast reaction and the time it takes, particularly when delayed films are required.

Figure 2 Patient after administration of intravenous contrast medium, showing left nephrogram and contrast coming down to the level of the stone.

Nephrotoxicity

The reported incidence of contrast‐induced renal failure is approximately 1%,5 while in the population with pre‐existing renal failure and diabetes mellitus, the risk of contrast‐induced nephrotoxicity is 25%.6

Metformin is an oral agent, used in the management of diabetes mellitus. Metformin is excreted unmetabolised by the kidney. It is not nephrotoxic; however, a major concern is the potential hazard of metformin‐induced lactic acidosis in those who develop contrast‐induced oliguria. In this setting, metformin can accumulate, resulting in the subsequent accumulation of lactic acid. Metformin‐induced lactic acidosis is fatal in half of the affected patients; however, it is a very rare complication.7

In patients with normal renal function metformin should be discontinued at the time of the IVU and withheld for the subsequent 48 h. For patients with abnormal renal function, metformin should similarly be discontinued at the time of the IVU and only be reinstated when renal function has been re‐evaluated and found to be normal.8

Contrast reaction

In the general population the incidence of contrast reaction is 5–10%, including mild reactions such as vomiting and urticaria, as well as more serious reactions such as bronchospasm and anaphylaxis (the risk of anaphylaxis is 157 per 100 000).9 The incidence of contrast reaction can be diminished in many cases with the use of expensive low osmolar contrast agents but it cannot be entirely eliminated.

Non‐contrast enhanced computed tomography

Unenhanced computed tomography (CT) provides an increasingly popular alternative for evaluating ureteric colic.

Advantages of CT

CT has the following advantages over IVU: it has higher sensitivity and specificity for calculus detection, it does not use intravenous contrast medium, it permits alternative diagnoses, and requires a shorter examination time.

The accuracy of non‐contrast CT in detecting stone disease has been indisputable with sensitivity, specificity and positive predictive value of CT being reported as 96%, 100% and 100%, respectively.10 CT can visualise all radiopaque stones, as well as radiolucent stones such as uric acid and cystine calculi (fig 3). When CT confirms the presence of a stone, a plain abdominal radiograph should be obtained to assess whether the stone is radiopaque. This is helpful as only the KUB radiograph is needed later to determine if the stone has moved or passed.

Figure 3 Non‐contrast computed tomography (CT) showing right vesicoureteric junction (VUJ).

Avoiding the use of intravenous contrast medium is perhaps the most distinct benefit of CT in this situation.

CT also provides an opportunity to identify extra‐urinary pathology during the primary investigation of patients in whom a definitive diagnosis is not always apparent. The reported incidence of extra‐urinary abnormality with CT is 6–12%.11 Those reported abnormalities include pelvic inflammatory disease, adnexal masses, tubo‐ovarian abscess, appendicitis, diverticulitis, cholecystitis, pancreatitis or unexpected malignancy. In some cases, intravenous contrast medium will be necessary for further characterisation of any of the unexpected findings.

Disadvantages of CT

An important limitation of CT is the fact that it does not permit functional evaluation of the kidneys and it is unable to assess the degree of obstruction. The presence of a stone does not necessarily mean that the kidney is obstructed. The relative lack of functional information derived from CT, compared with the renal excretory times evident during IVU, might compromise clinical management. However, some authors have suggested that secondary features of obstruction on CT which include hydronephrosis, hydroureter, renal enlargement and inflammatory changes of the perirenal fat, that are referred to as perinephric stranding, are a reliable parallel of delayed excretion on IVU.12

Another major disadvantage of CT is the higher radiation exposure of the patient compared with KUB or IVU. CT in this setting requires at least three times the radiation exposure of IVU and 10 times that of abdominal radiography and presents an additional lifetime risk of malignancy of 1 in 4000.13 Newer protocols involving reduced radiation exposure without compromising efficacy are developing and are likely to reduce further the radiation exposure from CT (table 1). Low‐dose and ultra low‐dose CT reduced radiation exposure by about 50% and 95%, respectively, compared with standard‐dose CT, with comparable detection rates of calculi and non‐stone‐associated abnormalities (table 2).14,15

Table 1 Radiation exposure of different imaging modalities.

| Technique | Radiation exposure (mSv) |

|---|---|

| KUB | 0.5–0.9 |

| IVU | 1.5–3.5 |

| Regular‐dose CT | 8–16 |

| Low‐dose CT | 2.8–4.7 |

| Ultra‐low dose CT | 0.5–0.7 |

CT, computed tomography; IVU, intravenous urography; KUB, plain radiograph of the kidney, ureter and bladder.

Table 2 Intravenous urography (IVU) versus computed tomography (CT).

| IVU | CT | |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | Less accurate | Indisputable accuracy |

| Intravenous contrast | Risk of nephrotoxicity or dangerous reaction to intravenous contrast medium | No intravenous contrast is necessary so no risk of nephrotoxicity or contrast reaction |

| Use in renal failure | Cannot be used in azotemia or known significant allergy to intravenous contrast agents | Can be used |

| Radiation | Less radiation dose | Standard CT requires at least three times the radiation exposure of IVU |

| Stones visualisation | Hard to see radiolucent stones, although indirect signs of obstruction may be apparent | With only rare exceptions it shows all stones clearly |

| Functional information | Shows relative kidney function | Does not give functional information |

| Anatomic information | Ureteric kinks, strictures or tortuosities are often visible | Cannot be seen |

| Other pathology | Cannot be used to evaluate other pathology | Demonstrates other pathology |

| Time | Relatively slow, may need multiple delay films, which can take hours | Fast |

Another disadvantage is that CT services are not universally available for 24 h period and a radiologist may be required for the accurate interpretation of the films.

Finally, in the current healthcare climate, cost and availability will always be central factors determining the use of CT in the acute setting. A frequent criticism of CT is that it costs more than IVU. However, when taking into account the advantage of reduced expenditure in terms of time and manpower for CT, it is suggested that indirect costs are much lower for CT scans.16

MANAGEMENT

Given that most ureteric stones will pass spontaneously, conservative treatment in the form of observation with analgesia is the preferred approach. Ureteric stones require radiological or surgical intervention only when the conservative treatment fails. The probability of spontaneous passage is based on a number of factors including stone size, stone position, degree of impaction and degree of obstruction. The likelihood of spontaneous stone passage decreases as the size of the stone increases (table 3).17 Most authors recommend that stone passage should not exceed 4–6 weeks due to the risk of renal damage.17

Table 3 Likelihood of passage of ureteric stones17.

| Size of stone | Likelihood of spontaneous passage (%) |

|---|---|

| ⩽2 mm | 97 |

| 3 mm | 86 |

| 4–6 mm | 50 |

| >6 mm | 1 |

Pathophysiology

The pain of ureteric colic is due to obstruction of urinary flow, with a subsequent increase in wall tension. Rising pressure in the renal pelvis stimulates the local synthesis and release of prostaglandins, and subsequent vasodilatation induces a diuresis which further increases intrarenal pressure. Prostaglandins also act directly on the ureter to induce spasm of the smooth muscle. Owing to the shared splanchnic innervation of the renal capsule and intestines, hydronephrosis and distension of the renal capsule may produce nausea and vomiting.

Analgesia

The choice of analgesia used in the management of acute ureteric colic is changing, with increasing use of non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Most studies have shown these drugs to be as effective as opioids, with the latter used as rescue medications.18 Opioids have higher rates of nausea, vomiting, and dizziness.

Data on the effect of opiates on ureteric tone suggest that they cause an increase or no change in tone. Opiate‐seeking patients might therefore spuriously present with symptoms of ureteric colic.

NSAIDs block prostaglandin‐induced effects. They also reduce local oedema and inflammation, and inhibit the stimulation of ureteric smooth muscle, which is responsible for increased peristalsis and subsequently increased ureteric pressure. Although NSAIDs reduce pain associated with ureteric colic, they may potentially interfere with the kidney's autoregulatory response to obstruction by reducing renal blood flow, and renal failure may be induced with pre‐existing renal disease. The choice of agent is generally based on clinician preference, personal experience and institutional culture.

Medical expulsive therapy

The traditional treatment indicated above has recently been improved by the application of active medical expulsive therapy (MET). Protocols were developed based on the possible causes of failure to pass a stone spontaneously, including muscle spasm, local oedema, inflammation, and infection. Regimens have commonly included a corticosteroid (to reduce local oedema through its anti‐inflammatory action), antibiotics (to prevent or treat urinary tract infection), as well as calcium antagonists and α‐blockers (agents directed towards stone‐induced ureteric spasm). Combination therapy is intended for short‐term use.

NSAID: NSAIDs have ureteric‐relaxing effects and, as such, can be considered to be a form of MET; yet the only randomised, double blinded, placebo‐controlled trial showed no difference in augmenting stones passage between NSAIDs and placebo.19

Calcium antagonists: Ureteric smooth muscle uses an active calcium channel pump in order to contract. Calcium antagonists suppress the fast component of ureteric contraction, leaving peristaltic rhythm unchanged. Therefore calcium channel blockers, which are commonly used in the treatment of hypertension and angina, have been used to relax ureteric smooth muscle and enhance stone passage.20

α‐Blockers: α1‐Adrenergic antagonists are currently commonly used as first‐line treatment in men with lower urinary tract symptoms. Both α and β adrenoreceptors have been shown to exist within the ureter, particularly in the lower and intramural portions. α1‐Adrenergic antagonists inhibit the basal tone, peristaltic wave frequency and the ureteric contraction in the intramural parts. As a result the intraureteric pressure below the stone decreases and elimination of the stone can be achieved.21

Patients treated with calcium antagonists or α‐blockers had a 65% greater likelihood of spontaneous stone passage than patients not given these drugs. Calcium‐channel blockers and α‐blockers seemed well tolerated.22,23,24,25

The addition of corticosteroids might have a small advantage but the benefit of drug therapy is not lost in those patients for whom corticosteroids might be contraindicated.26,27,28

There are additional benefits which seem to be associated with MET. Patients have a significantly reduced time to stone passage, significantly fewer pain episodes, lower analogue pain scores, and need significantly lower doses of analgesics.

When conservative therapy fails, the choice of treatment lies between shock wave lithotripsy and ureteroscopy. Surgical management is beyond the scope of this article and it is not discussed here.

CONCLUSION

Acute ureteric colic is a common surgical emergency. There is a shift towards using non‐contrast CT in evaluating ureteric colic. MET has shown promise in increasing the spontaneous stone passage rate and relieving discomfort while minimising narcotic usage.

Abbreviations

CT - computed tomography

IVU - intravenous urography

KUB - plain radiograph of the kidney, ureter and bladder

MET - medical expulsive therapy

NSAIDs - non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs

PUJ - pelviureteric junction

VUJ - vesicoureteric junction

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: none stated

References

- 1.Sierakowski R, Finlayson B, landes R R.et al The frequency of urolithiasis in hospital discharge diagnoses in the United States. Invest Urol 197815438–441. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mutgi A, Williams J W, Nettleman M. Renal colic: utility of the plain abdominal roentgenogram. Arch Intern Med 19911511589–1592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sheafor D H, Hertzberg B S, Freed K S.et al Non‐enhanced helical CT and US in the emergency evaluation of patients with renal colic: prospective comparison. Radiology 2000217792–797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miller O F, Rineer S K, Reichard S R.et al Prospective comparison of unenhanced spiral computed tomography and intravenous urogram in the evaluation of acute flank pain. Urology 199852982–987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Levy E M, Viscolli C M, Horwitz R I. The effect of acute renal failure on mortality: A cohort analysis. JAMA 19962751489–1494. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barrett B J, Carlisle E J. Meta analysis of the relative nephrotoxicity of high‐ and low‐osmolality iodinated contrast media. Radiology 1993188171–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thompson N W, Thompson T J, Love M H S.et al Drugs and intravenous media. BJU Int 200085219–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Royal College of Radiologists Royal College of Radiologists' guidelines with regard to metformin‐induced lactic acidosis and x‐ray contrast medium agents. London: The Royal College of Radiologists, 1999992 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shehadi W M, Toniolo G. Adverse reactions to contrast media: a report from the Committee on Safety of Contrast Media of the International Society of Radiology. Radiology 1980137299–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Worster A, Preyra I, Weaver B.et al The accuracy of noncontrast helical computed tomography versus intravenous pyelography in the diagnosis of suspected acute urolithiasis: a meta‐analysis. Ann Emerg Med 200240280–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ahmad N A, Ather M H, Rees J. incidental diagnosis of disease on un‐enhanced helical computed tomography performed for ureteric colic. BMC Urol 200332–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith R C, Verga M, Dalrymple N.et al Acute ureteral obstruction: value of secondary signs of obstruction of the urinary tract on unenhanced helical CT. Am J Roentgenol 19961671109–1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Denton E R, Mackenzie A, Greenwell T.et al Unenhanced helical CT for renal colic: is the radiation dose justifiable? Clin Radiol 199954444–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meagher T, Sukumar V P, Collingwood J.et al Low‐dose computed tomography in suspected acute renal colic. Clin Radiol 200156873–876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kluner C, Hein P A, Gralla M D.et al Does ultra‐low‐dose CT with a radiation dose equivalent to that of KUB suffice to detect renal and ureteral calculi? Comput Assist Tomogr 20063044–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pfister S A, Deckart A, Laschke S.et al Unenhanced helical computed tomography vs intravenous urography in patients with acute flank pain: accuracy and economic impact in a randomized prospective trial. Eur Radiogr 2003132513–2520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miller O F, Kane C J. Time to stone passage for observed ureteral calculi: a guide to patient education. J Urol 1999162688–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holdgate A, Pollock T. Nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs versus opioids for acute renal colic. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004(1)CD004137. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Laerum E, Ommundsen O E, Gronseth J E.et al oral diclofenac in the prophylactic treatment of recurrent renal colic. A double‐blind comparison with placebo. Eur Urol 199528108–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Salman S, Castilla C, Vela N R. Action of calcium antagonists on ureteral dynamics. Actas Urol Esp 198913150–152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sigala S, Dellabella M, Milanese G.et al Evidence for the presence of α 2 adrenoceptor subtypes in the human ureter. Neurourol Urodyn 200524142–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Porpiglia F, Destefanis P, Fiori C.et al Effectiveness of nifedipine and defluzacort in the management of distal ureteral stones. Urology 200056579–583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dellabella M, Milanese G, Muzzonigro G. Efficacy of tamsulosin in the medical management of juxtavesical ureteral stones. J Urol 20031702202–2205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dellabella M, Milanses G, Muzzonigro G. Randomized trial of the efficacy of tamsulosin, nifedipine and phloroglucinol in medical expulsive therapy for distal ureteral calculi. J Urol 2005174167–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hollingsworth J M, Rogers M A M, Kaufman S.et al medical therapy to facilitate urinary stones passage: a meta analysis. Lancet 20063681171–1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dellabella M, Milanses G, Muzzonigro G. medical expulsive therapy for distal ureterolithiasis: Randomized prospective study on the role of corticosteroids used in combination with tamsulosin‐simplified treatment regimen and health‐related quality of life. 200566712–715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Salehi M, Fouladi M M, Shier H.et al Does methylprednisolone acetate increase the success rate of medical therapy for patients with distal ureteral stones. Eur Urol Suppl 2005424–28. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pearle M S. Comment on medical therapy to facilitate urinary stones passage. Lancet 20063681138–1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]