Abstract

The UK chief medical officer's recommendations for the re‐licensing and performance management of doctors will mean a move from a formative towards a summative role for appraisal and its adjunct, the personal development plan. Where does this leave medical educators trying to promote reflective learning? It is taken for granted that self‐directed learning is the sine qua non of all adult learning. But is it? This review re‐evaluates self‐directed learning and its corollary, the personal development plan, in the light of the chief medical officer's report, seeking the evidence behind today's accepted educational practice. It discovers a reality which challenges assumptions long enshrined in medical education.

Until now, UK doctors have had no obligation to demonstrate their continuing fitness to practise. In calling for National Health Service developmental appraisal to measure performance and become the basis for re‐licensure,1 the chief medical officer (CMO) has effectively moved the personal development plan (PDP) into the minimum standards arena and called into question its use as a formative development tool. This literature review suggests he may be right.

Grant and Stanton's influential 1999 review into the effectiveness of continuing professional development2 called for a focus on the process, based on individual needs. This resulted in the reforms of appraisal and the PDP, now contractual requirements for most UK doctors, who will often be familiar with them through their training schemes. But the PDP diverts the focus from process to content. It can be argued that by restricting study to the items on the plan, it promotes prescriptive over experiential learning. Tutors have subsequently attempted to increase health professionals' control of their learning by making it an object of reflection. This may work for some, but not all. Candy3 pointed out in 1991: “There may be limited transfer of self‐directed competence from one context to the next and the pursuit of generalised strategies is probably ill advised and foredoomed.” Is self‐directed learning so important? Is there any evidence that PDPs are effective?

WHAT IS SELF‐DIRECTED LEARNING?

All adults learn; 80–100% of adults engage in some form of learning activity throughout their lives,3 but only 20% of these do so in a formal educational setting.4 Knowles defined self‐directed learning5 as a process in which individuals take the initiative in diagnosing their learning needs, designing learning experiences, locating resources and evaluating their learning. From fashioning a coracle, to the Socratic method of thinking for oneself, it implies a high order cognitive activity, and one which distinguishes the adult learner from the child and adolescent. But in enunciating the assumptions of andragogy6 (“the art and science of helping adults learn”) Knowles inadvertently heralded a new philosophy, setting Freire's Pedagogy of the oppressed7 in a logical theoretical framework; adult educators searching for a professional identity seized upon his unproven assumptions as axioms8,9 which took self‐directed learning as the sine qua non of all adult learning. But is it?

WHAT SELF‐DIRECTED LEARNING IS NOT

Self‐directed learning is not a philosophy, nor is it a set of techniques to be applied by an institution wanting to teach a self‐directed programme. It is an internalised process related to motivation and self‐identity,8 something that happens within a person, not something that is done to them. Where is the evidence for this?

Tough10 confirmed that when adults decide to learn they first invest time and energy in checking the potential benefits; as Knowles put it, “Learners need to know why they need to know”. But Tough also found that those adults devalue their work if not validated by some external authority. Hence the rational for Brookfield's principle of effective facilitation8: the self‐directed‐learner must be supported and reassured. Yet it is he who points out that this has now become unchallenged academic orthodoxy.8

WHY ARE SOME LEARNERS MORE SELF‐DIRECTED THAN OTHERS?

Since there are many alternative models (table 1),11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20 why must it be necessary or even desirable for adults to be self‐directed in order to learn? Brookfield points out that self‐directed learning alone has less successful outcomes than a mix of self‐directed learning and group learning.21 If all adults are self‐directed, why are some more self‐directed than others?22 What factors determine how self‐directed an individual is?

Table 1 Learner‐centred models of learning.

| Self‐efficacy | In an extension to Tough's work, Bandura11 used the term “self‐efficacy” to describe the judgements people make, sound or unwise, of their ability to deal with situations, before commencing them. Their actions depend on these judgements, which are informed, in order of importance by knowledge of their previous performance, observing others, encouragement of others and physiological state. In this model, self efficacy can be raised or lowered by early success or failure. It has evolutionary advantage, not necessarily linked to truth. |

| Reflective thinking | For Dewey12 the route to genuine freedom was based on five steps: suggestions for a solution lead to clarification of the problem, formation of hypotheses, reasoning on the meaning of the possible outcomes before testing the hypotheses. |

| Experiential learning | Critical reflection on experience, plus the formulation of new hypotheses which are then tested by further action, in circuits of the learning cycle (Kolb13), so giving meaning to learning (Mezirow14): but based on Rogers15 for whom the essential characteristics were personal involvement, self‐initiation, pervasive stimulation of feelings and cognitive aspects of personality; perceived as satisfying a need (Maslow16). |

| Reflective practice | For Schön17 theory based competence in “zones of mastery” is modified practically by the unexpected. It has two components: “reflection in action” with immediate modification of practice, based on integration of the new learning with past experience, and subsequent “reflection on action” to develop “zones of artistry” by anticipating the unanticipated. |

| Redefinition | Danis and Tremblay18 challenged the importance of the learning cycle and suggested that random determinants could be more significant in successful learning than evaluation and planning. They found that many self taught adults have a heuristic approach to learning, constantly redefining their objectives without any predetermined patterns, and without consciously identifying their learning needs. That does not mean that they do not reflect, simply that they may need to reflect for much shorter periods than others (see Schön17 above). Some of the best learning occurred due to fascination, not to solve problems. |

| Staged self‐direction | Grow19 points out that learners are not empty vessels waiting to be filled, but respond in different ways to the stream of knowledge and its flow. The astute facilitator matches teaching stage with learning stage. |

| Recursion | Recursive teaching20 accepts the reality of looping from one matched stage to another and back again, as appropriate to the topic, time available or student experience and expectation. The corollary is recursive learning—learners iteratively use a mixture of styles and techniques as appropriate. |

In his own literature review, Candy3 found that a number of paired traits had been associated with the ideal of self‐directedness—for example, logical/analytical, curious/open, reflective/self aware—suggesting that it was not a feature of every adult learner. Andragogy would have teachers attempt to develop these traits in learners, to make them more self‐directed. Teachers can encourage curiosity, but can they make someone more open‐minded, more logical? The work of Jung23 and Myers24 suggested this might depend more on behavioural types.

DOES SELF‐DIRECTION DEPEND ON LEARNING STYLE?

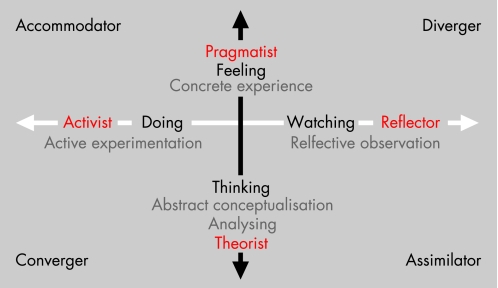

In Kolb's model of experiential learning, learners choose how to acquire information (either concretely through the senses or abstractly by analysing) and process it (reflectively by watching or actively by doing); hence the learning style inventory25 and the learning cycle.26 To Honey and Mumford27 Kolb's assimilators became reflector‐theorists; accommodators became activist‐pragmatists, etc (fig 1).

Figure 1 Kolb's experiential learning styles are in black, Honey and Mumford's in red. Adapted from Robinson.34

To Riding and Cheema28 and Rayner29 the key was not learning style but cognitive style. This develops between 6 and 9 years old, not in adolescence.30 Curry showed how these may be related, with cognitive style more deeply embedded than learning style.31

Baker et al,32 Allinson et al33 and Robinson34 linked a propensity to take risks with the activist/accommodator‐converger styles. Reflector/assimilator‐divergers have some preference for lectures and non‐group activities; they deliberately exclude themselves from risk. Could it be that they are therefore more self‐directed? In 1984 Pratt35 enunciated what many had already assumed, that self‐directed learning is associated with autonomy—that is, with Witkin's (1949) “field‐independent” thinkers.36 These field‐independents have close connections with the reflector/assimilator‐diverger learning style. It was therefore a logical deduction, and one that fitted nicely with the aspirations of adult educators, that self‐directed learners would tend to be reflectors, and therefore in order to support learners in becoming more self‐directed, they should be encouraged to adopt a more reflective style. In spite of its undeniable logic, common sense and convenience, this deduction was spurious.8 Brookfield had already demonstrated the reverse.37

In work later corroborated by Thiel,38 Brookfield had looked at real, successful self‐directed adult learners and found they were more likely to be field‐dependent, heuristic, activist‐accommodators. The key was that these were extrinsically motivated and gregarious, willing to network in order to problem solve. The autonomous field‐independent/reflectors kept themselves to themselves and sought less help. Although field‐dependent/activist‐pragmatists looked to others to mediate their learning, they possessed the single most important “measure of self‐direction”39,40—their ability to act on their critical reflection. The reflectors merely reflected. As Eva discussed in an editorial in 2005, the key determinants of self‐direction might not be learning style, nor indeed personality type, but the meta‐cognitive processes that determine both.41

IS CURRENT PRACTICE EVIDENCE BASED?

Why then, 20 years after Brookfield pointed all this out, are health professionals being forced to use PDPs to “become more reflective” when this could demotivate the most self‐directed? True, Brookfield says they need support—just not in this way. Could it be that medical educators have reluctantly accepted this practice, because the alternatives in maintaining medical competence are too draconian? Or is the heuristic, trial and error approach, for millennia the mainstay of scientific advance, hard to justify in 21st century medico‐legal terms?

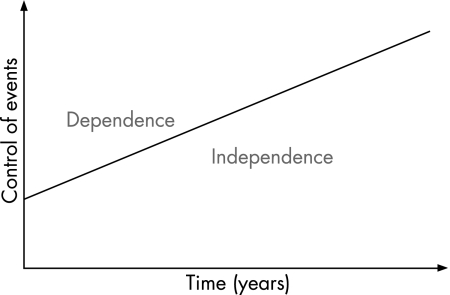

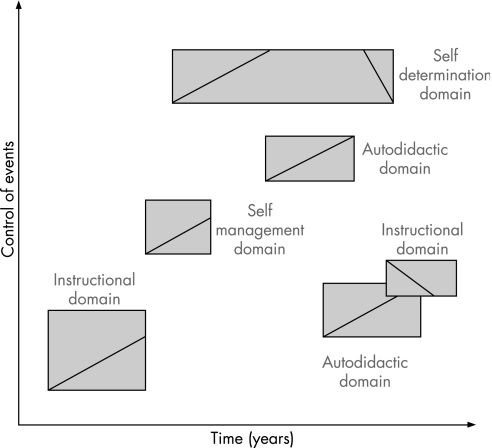

The canon of evidence on self‐directed learning in healthcare is legion, but much of it is not directly comparable since “experts” mean different things by self‐directed learning. The basic model sees control transferred from teacher to learner with growing independence over time (fig 2).

Figure 2 A simple model of self‐direction. Adapted from Candy.3

But this is too simplistic. Candy3 reminds us that the term self‐direction as referred to in the literature means four different things (table 2). The first two are concerned with self‐direction as method or process: (1) the degree of control a learner has over the mode of instruction; (2) autodidaxy (“teach‐yourself”, or the independent pursuit of learning). The next two are concerned with self‐direction as outcome or goal: (3) self‐management of learning; (4) self‐determination of destiny.

Table 2 Four domains of “self‐direction”.

| Self‐direction as: | |||

| Method/process | 1 | Learner control | (over instruction given) |

| 2 | Autodidaxy | (teach yourself) | |

| Self‐direction as: | |||

| Outcome/goal | 3 | Self‐management | (of learning) |

| 4 | Self‐determination | (of destiny) |

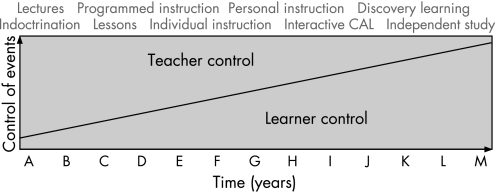

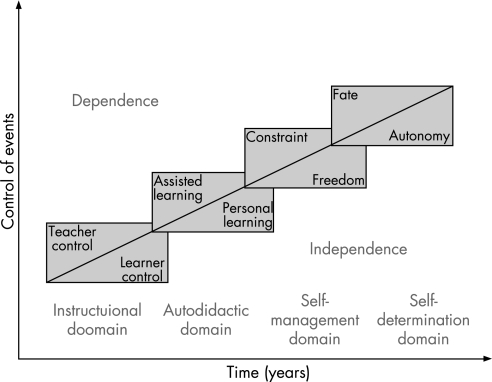

Each domain can be represented as the change in control over time (for example, the instructional domain shown in fig 3).

Figure 3 Candy's learner‐control continuum: instructional domain. Adapted from Candy3 and Millar.42

SIX PROBLEMS

Dittman43 points out that some educators (for example, Marbeau44) wrongly assumed that simply “doing self‐directed learning” at an instructional or autodidactic level leads to autonomy (fig 4), and that these four different but overlapping domains can be superimposed chronologically on the simplistic model (for example, Davis and Thompson45).

Figure 4 Domains of self direction: idealised version. From an idea in Candy.3

In reality these occur randomly (fig 5), as different people operate in different domains at different times in their lives, as a result of their upbringing, previous learning experiences and the “organising circumstances” over which they have little control.46 So they will choose to be more or less self‐directed depending upon their constructions and their confidence in a particular subject at a particular time.47 In other words, self‐directed learning is context specific.48

Figure 5 Domains of self direction: a realistic example. From an idea in Candy.3

Second, given that self‐directed learning is context specific, it is learners' experiences that are important in any research, not their test results, since those may vary with the context. Qualitative studies are therefore most suitable for all but the instructional domain of this relativist topic.49 Yet they are swamped by quantitative ones.50,51 Meta‐analyses only compound the error.

Third, research conclusions from studies in one domain alone are applied erroneously as evidence across all domains—for example, randomised controlled studies comparing traditional teaching approaches with specific techniques that allow the learner a small degree of choice, are valid only in the instructional domain, yet purport to demonstrate the effectiveness of self‐directed learning globally or across disciplines.3

Fourth, it is disingenuous to restrict learner‐control to a limited choice—for example, between lectures or a CD‐ROM. Learning is holistic. As Boucouvalas and Pearse state: “When learners set the outcomes, that is self‐directed learning. When teachers set the outcomes, that is benevolent pedagogy.”52 Which of these models best fits undergraduate medicine in the UK in 2007? It may be appropriate to teach medicine in this way because medical students are not capable of assessing their learning needs,53 but why call it self‐directed learning?

Fifth, there is overwhelming evidence that doctors also are incapable of assessing their learning needs accurately.45,54,55,56,57 “If I am authentically learning I will not be able to predict where I go with accuracy. If I could predict with accuracy…I already know what I am purporting to learn…I have already arrived at where I have decided to go. The goal specified…is not the true goal. The true goal, as Sartre has indicated, is what we desire at the end…not at the beginning” (Burstow58). Or as Keil put it: “How can I know what I don't know when I don't know what I don't know?”59 Wherefore the PDP now?

Finally, there is no evidence that self‐directed as opposed to teacher‐directed learning improves learning outcomes.60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67

WHY SELF‐DIRECTED LEARNING?

Self‐directed learning has been shown to be associated with increased curiosity, critical thinking, quality of understanding, retention and recall, better decision making, achievement satisfaction, motivation, competence and confidence.65,67,68 These are all important qualities in doctors, not measurable by quantitative studies, and reason enough to support self‐direction. The value in doing so is not to optimise the learning outcomes in terms of scores on a multiple choice questionnaire but, by encouraging participation, to reduce the numbers of demotivated doctors who drop out of learning.69,70 Performing well in any task requires cognitive and meta‐cognitive functioning: knowledge of the task, and knowledge of one's own motives, resources and constraints in context, in order to plan strategically. As Biggs states, the task of learning is no different.71 Therefore self‐directed learning, which exemplifies this par excellence, as well as being the most natural form of learning, is also associated with high quality learning.72

The evidence base on self‐directed learning

There is no evidence that self‐directed learning leads to autonomy

Research conclusions are being applied erroneously

Learners' experiences are key, not their results

Restricting learner‐control has no part in self‐directed learning

Doctors are incapable of accurately assessing their learning needs

There is no evidence that self‐directed learning improves outcomes But…

Self‐directed learning is high quality learning

In the setting of UK general medical practice, relative professional isolation means that self‐direction is a fact of life. Therefore the onus is on facilitators to help general practitioners (GPs) learn effectively that which is relevant. Continuing medical education based on personal preference is now perceived to be financially untenable in a system of rationed healthcare,73,74 and has been superseded by a programme of appraised personal development planning, optimistically based on assessment of personal learning and service needs. The formative appraisal part of the process has been largely welcomed and valued by the profession.75 Acceptance and usefulness of the PDP is less clear. Its aims were supposedly to increase autonomous reflective practice (which is perceived as “safer for patients” than heuristic learning) by attempting to make GPs more self‐directed, and thereby improve health outcomes. But the link with revalidation has only confirmed the political agenda in imposing “self‐direction” on an already quite autonomous group of professionals76 and there is no theory or existing evidence to support any of it, although the research methodology to date has been flawed, debunked by Brookfield and Candy years ago.

WHY PERSONAL DEVELOPMENT PLANS?

The PDP was already out of date when introduced in the UK, based on an entirely fallacious understanding of self‐directed learning, and discredited by Frewin in 1976.77 The plan stemmed from Flanagan's 1970 assertion78 that “a self‐directed learner should have a reasonable degree of skill and decision making in planning, which should include…the ability to analyse and define problems and prepare a sequential plan using a clear statement of desired outcomes and working back to obtain a definite schedule and a set of procedures for determining the required progress at each point.” Indeed she should. But to paraphrase Candy, what if she is not a reflector with mechanical, linear and analytical cognitive processes? What use is this plan to her? It sits in a draw, giving the impression that the mandate to ensure the doctor's competence has been filled,79 but is in reality redundant. Evans80 suggested PDPs were well received by 80% of GPs, influencing their development and quality of patient care, but the study pre‐dated UK national appraisal and those GPs chosen had elected to use a PDP, suggesting that this appealed to their learning preferences. Subsequent studies which reduced sample bias are more circumspect81; 50% of GPs regard PDPs as hoops to be jumped.82 Their mechanistic production devalues the self‐directed element of formative appraisal.83,84

Personal developments plans (PDPs)

PDPs are founded on a misconception

The practice of promoting reflective learning via PDPs is not evidence based

The PDP is probably more useful to the facilitator than the learner

A PDP is not essential for successful self‐directed learning

The concept of the self‐directed learner is more complex than fitting a simple reflective model. People's propensity to control their own learning is not necessarily determined by increasing their reflective abilities, but by meta‐cognitive processes which depend upon personality type, learning style preference, cognitive style, past experiences, situation pertaining, subject studied, acquired competencies, or all or none of these. A PDP may help or hinder.85 For doctors who proceed heuristically, lapping the learning cycle many times a day, planning learning a year in advance is demotivating as well as pointless, due to the sense of inadequacy engendered. But these may well be self‐directed learners. They are not unsafe practitioners. Schön's “reflection‐in‐action” (table 1) is not only more relevant for them, but may be more important than “reflection‐on‐action” generally, for it occurs at the coal face of decision making. We may know what we should do in a situation, but it is what we actually do that affects patients. Bandura's judgements in self‐efficacy (table 1) are influenced by heuristics.86 Appraisal and reflective practice, as currently advocated across all health professions, emphasise reflection‐on‐action and ignore reflection‐in‐action, and we know that doctors are bad at identifying their own weaknesses when they do reflect‐on‐action.59,87,88 They are not unique; self‐belief is a selective advantage89 and this casts doubt on the relevance of self‐assessment. Does it really address unconscious incompetence? Although reflection‐in‐action can be unconscious it appears to involve a stepping up of cognitive resources90 and is modifiable.91 Patients' unmet needs (PUNS) and doctors' educational needs (DENS) attempt to crystallise the immediacy of this reflection‐in‐action. Reflection‐on‐action is still important yet the paradox of the PDP is that it is potentially a useful learning tool for those to whom it holds least appeal but who need a structured approach‐wholist activist/pragmatists, who tend to include on it tasks they have already completed; it is probably of no use to those analyst/theorist‐reflectors who have their own more detailed portfolio anyway, but quite enjoy filling in the PDP. At worst, it is counterproductive for the enthusiastic obsessive who fails to complete an unrealistic self‐delegated agenda.

If it is to remain, the PDP will need to be short term, tailored to the individual and incorporating strategic challenges, not just in order to appeal to the activist learner but because, as Björk has shown,92 “desirable difficulties” increase the accuracy of self‐assessment, which nicely fits the cognitive research93 as well as Freire's praxis.94 The beauty of self‐directed learning is that even without a PDP, it overrides all these complex issues and opts, by definition, for the most appropriate route to personal learning, although still requiring support. But without that PDP, how can the facilitator determine what has or will be learned? Herein lies the rub: the PDP probably has more use to educators and assessors, than learners.

Key references

Candy P. Self‐direction for lifelong learning, San Francisco: Jossey‐Bass Higher and Adult Education Series, 1991.

Brookfield S. Understanding and facilitating adult learning. Milton Keynes: Open University Press, 1986.

Norman G. The adult learner: a mythical species. Acad Med 1999;74:886–9.

Spear G, Mocker D. The organizing circumstance: environmental determinants in self‐directed learning. ED226148, ERIC Clearinghouse on Adult, Career & Vocational Education, Ohio State University, 1981.

ALTERNATIVES?

Grant has subsequently pointed out that needs assessment alone can stifle creative learning and does not improve outcomes unless in the appropriate context.95 She also reasserts the findings of Davis96 and Bandara and Calvert83 that doctors already have their own, if flawed, ways of assessing their needs and asks if these should be the starting point of new systems for formative professional improvement.

The focus for the immediate future needs to be on the individual, not the process or content. As Asadoorian and Batty state,97 we need facilitation based on the needs of the individual, and tailored to individual preference, using personalised tools ascertained from each individual appraisal. Lyons has called for a system that considers individuals' learning and cognitive styles.98 We need to inculcate “personalised, surgery‐based climates of enquiry”. We need qualitative research into the value individuals derive from the process, into individual perceptions of the effect of PDPs on reflective practice, and into relevant individual health outcomes99; population benefits may come later. We will need to find an alternative to PDPs at least for formative purposes—they may still have a role in performance appraisal. That alternative must allow doctors to inform their future learning by whatever method they choose, as long as the outcome is patient centred. But qualitative research should precede hypotheses, so we will have to wait until we know the results, before we can predict what form the PDP replacement should take. It should be remembered though that doctors still have a responsibility to manage and resource their own development,84 and as we know from Brookfield, will still require some form of ongoing support with appraisal.

Further reading

Cook D. Learning and cognitive styles in web based learning: evidence and application. Acad Med 2005;80:266–78.

Hiemstra R. Self‐directed learning. In: Husen T, Postlethwaite TN, eds. The international encyclopedia of education, 2nd ed. Oxford: Pergamon Press, 1994. http://home.twcny.rr.com/hiemstra/sdlhdbk.html

Houle C. The inquiring mind: a study of the adult who continues to learn. Madison, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press, 1961.

Rousseau J. Emile. London: Orion, Phoenix Press, 1993 Tr. 1762.

Taylor M. Self directed learning: more than meets the observer's eye. In: Boud D, Griffin V. Appreciating adults learning: from the learners' perspective. London: Kogan Page, 1987.

To quote Newman and Peile: “Any move towards common standards in education must not obscure the need for medical educators to remain flexible and agile in responding to different learners' needs. Educators need to improve their skills in facilitation, judicious application of educational theory and mentoring.”100

CONCLUSION

The aims of andragogy and self‐directed learning were honourable. They should be pursued in a reasoned, informed, evidence‐based fashion in continuing medical education, acknowledging complexity and avoiding unsubstantiated claims, academic orthodoxy and political expedience. Let the right research questions be asked and the right research methods be used. Let what has already been written be read again carefully, to distinguish fact from fiction. Let there be a sound basis for the support of self‐directed health professionals.

Abbreviations

CMO - chief medical officer

DENS - doctors' educational needs

GP - general practitioner

NHS - National Health Service

PDP - personal development plan

PUNS - patients' unmet needs

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: none stated

References

- 1.Department of Health Good doctors, safer patients: proposals to strengthen the system to assure and improve the performance of doctors and to protect the safety of patients. A report by the Chief Medical Officer. London: DOH, 2006, http://www.dh.gov.uk/PublicationsAndStatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidanceArticle/fs/en?CONTENT_ID = 4137232&chk = KW63va Free full text (Accessed 24 Aug 2006). Pages 194 and 197, recommendations 18 and 28, http://www.dh.gov.uk/assetRoot/04/13/72/91/04137291.pdf (Accessed 24 Aug 2006)

- 2.Grant J, Stanton S.The effectiveness of continuing professional development: a report for the chief medical officer's review of CPD in practice. Edinburgh: ASME, 1999

- 3.Candy P.Self‐direction for lifelong learning. San Francisco: Jossey‐Bass Higher and Adult Education Series, 1991

- 4.Tough A. Major learning efforts: recent research and future directions. Adult Educ (US) 197828250–263. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Knowles M.Self directed learning. Cambridge: Cambridge Adult Education, 1976

- 6.Knowles M. Andragogy in action: applying modern principles of adult learning. San Francisco: Jossey‐Bass, 1984

- 7.Freire P.Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York: Herder & Herder, 1970

- 8.Brookfield S.Understanding and facilitating adult learning. Milton Keynes: Open University Press, 198696

- 9.Norman G. The adult learner: a mythical species. Acad Med 199974886–889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tough A.The adult's learning projects: a fresh approach to theory and practice in adult learning. Toronto: Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, 1979

- 11.Bandura A. Social foundations of thought & action: a social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice‐Hall, 1986

- 12.Dewey J.How we think. New York: Dover Publications, 2007 (1910 reprint)

- 13.Kolb D.Experiential learning: experience as the source of learning and development. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 1984

- 14.Mezirow J. A critical theory of adult learning and education. Adult Learning 19813121 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rogers C.Freedom to learn: a view of what education might become. Columbus, Ohio: Merril 1969

- 16.Maslow A.Towards a psychology of being. New York: Van Nostrand, 1968

- 17.Schön D.Educating the reflective practitioner: toward a new design for teaching and learning in the professions. San Francisco: Jossey‐Bass, 1987

- 18.Danis C, Tremblay N. Critical analysis of adult learning principles from a self‐directed learner's perspective. Proceedings: Adult Educ Research Conference, No.26 Tempe, Arizona State University 1985

- 19.Grow G. Teaching learners to be self directed. Adult Education Quarterly 199641125–149. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mohanna K, Wall D, Chambers R.Teaching made easy: a manual for health professionals. Abingdon: Radcliffe, 200437–38.

- 21.Brookfield S. Successful independent learning of adults of low educational attainment in Britain: a parallel educational universe. Proceedings of 23rd Annual Educ Research Conference, University of Nebraska, Lincoln 198248–53.

- 22.Brockett R, Hiemstra R.Self‐direction in adult learning: perspectives on research, theory & practice. New York: Routledge, 1991

- 23.Jung C.Psychological types. Florida: Center for the Application of Psychological Type, 1923

- 24.Briggs Myers I, Myers P.Gifts differing: understanding personality type. Palo Alto: CPP Books, 1980

- 25.Kolb D.Learning style inventory technical manual. Boston: McBer, 1976

- 26.Kolb D.Experiential learning: experience as the source of learning and development. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 1984

- 27.Honey P, Mumford M.Manual of learning styles. Maidenhead: Peter Honey Publications, 1982

- 28.Riding R, Cheema I. Cognitive styles: an overview and integration, Educ Psychol 199111193–215. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rayner S. Reconstructing style differences in thinking & learning: profiling learning performance. In: Riding R, Rayner S, eds. International Perspectives on Individual Differences. Vol.1 Cognitive styles Stamford, Connecticut: Ablex Publishing Corp, 2000

- 30.Norman G. The adult learner: a mythical species. Acad Med 199974886–889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Curry L. An organization of learning style theory and constructs. In: Curry L, ed. Learning style in continuing medical education. Ottawa: Canadian Medical Association, 1983115–123.

- 32.Baker J, Wallace C, Bryans W. Analysis of learning styles, Southern Medical J 1985781494–1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Allison J, Kiefe C, Cook E. The association of physician attitudes about uncertainty and risk taking with resource use in a Medicare HMO. Medical Decision Making 199818320–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Robinson G. Do general practitioners' risk taking propensities and learning styles influence their CME preferences? Medical Teacher 20022471–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pratt D. Andragogical assumptions: some counter intuitive logic. Proceedings of the Adult Educ Research Conference, 25, Raleigh, North Carolina State University 1984

- 36.Witkin H. The nature and importance of individual differences in perception. J Personality 194918145–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brookfield S. Independent adult learning. Studies in Adult Education 1981(1)15–27.

- 38.Thiel J. Successful self directed learners' learning styles, Proceedings of the Adult Educ Research Conference, 25, Raleigh, North Carolina State University 1984

- 39.Guglielmino L.Development of the self‐directed learning readiness scale. University of Georgia: Dissertation Abstracts International, 1977386467A [Google Scholar]

- 40.Oddi L. Development of an instrument to identify self‐directed continuing learners. Adult Educ Quarterly 19863697–107. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Eva K. Dangerous personalities [editorial]. Advances in Health Sciences Education 200510275–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Millar C, Morphet A, Saddington J. Case study: curriculum negotiation in professional adult education. J Curriculum Studies 198618437 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dittman J. Individual autonomy: the magnificent obsession. Educ Leadership 197633463–467. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Marbeau V. Autonomous study by pupils in secondary schools. Educ Culture 197614–21.

- 45.Davis D, Thomson M. Implications for graduate and undergraduate education derived from quantitative research in CME: lessons learned from an automobile. J Cont Educ Health Prof 19961675–81. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Spear G, Mocker D.The organizing circumstance: environmental determinants in self‐directed learning. ED226148, ERIC Clearinghouse on Adult, Career & Vocational Education. Ohio State University 1981

- 47.Campbell V. Self direction & programmed instruction for five different types of learning objectives. Psychology in the Schools 19641348–359. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ross L, Nisbett R.The person and the situation: perspectives in social psychology. New York: McGraw‐Hill, 1991

- 49.Säljö R.Qualitative differences in learning as a function of the learner's conception of the task. Göteborg studies in educational sciences 14. Göteborg: University of Göteborg, 1975

- 50.Caffarella R. Qualitative research in self directed learning. Annals of Am Ass Adult Continuing Educ Tulsa1988

- 51.Owen T.Self‐directed learning in adulthood: a literature review. ED461050, ERIC Clearinghouse on Adult, Career & Vocational Education. Ohio State University 2002

- 52.Boucouvalas M, Pearse P. Self directed learning in an other‐directed environment: the role of correctional education in a learning society. J Correctional Educ 198232(4)31–35. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gordon M. A review of the validity and accuracy of self‐assessments in health professions training. Acad Med 199166762–769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Laxdal O. Needs assessment in continuing medical education: a practical guide. J Med Educ 198257827–834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sibley J, Sackett D. A randomised trial of continuing medical education. N Engl J Med 1982306511–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tracey J, Arroll B. The validity of general practitioners' self assessment of knowledge: cross sectional study. BMJ 19973151426–1428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wun Y, Dickinson J. Do physicians know what they should learn? Educ Primary Care 200213504–510. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Burstow B. Adult education: a Sartrian based perspective Int J Lifelong Educ 19843(3)193–202. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Eva K, Cunnington J. How can I know what I don't know? Personalities. Advances in Health Sciences Education 20049211–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.McKeachie W. The improvement of instruction. Review of Educ Research 196030351–360. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gruber H, Weitman M.Self‐directed study: experiments in higher education. Behaviour Research Laboratory Report No. 19. Boulder: University of Colorado, 1962

- 62.Gruber H, Weitman M. The growth of self‐reliance. School & Society 196391222–223. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Campbell V. Self direction & programmed instruction for five different types of learning objectives. Psychology in the Schools 19641(4)348–359. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dubin R, Taveggia T.The teaching learning paradox: a comprehensive analysis of college teaching methods. Eugene, Oregon: Centre for the Advanced Study of Educational Administration, University of Oregon, 1968 (meta‐analysis 1924–1965),

- 65.Fry J. Interactive relationship between inquisitiveness and student control of instruction. J Educ Psychology 197263459–465. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kotaska J, Dickinson G, Effects of a study guide on independent adult learning Adult Educ (US) 1975;25:161–168. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rosenblum S, Darkenwald G. Effects of adult learner participation in course planning on achievement and satisfaction. Adult Educ Quarterly 198333147–153. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Geis G. Student participation in instruction: student choice. J Higher Educ 197647249–273. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Boshier R. Motivational orientations of adult education participants: a factor analytic exploration of Houle's typology. Adult Educ (US) 197121(2)3–26. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Boshier R. Educational participation & dropout; a theoretical model. Adult Educ (US) 197323(4)255–282. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Biggs J. Enhancing learning skills: the role of metacognition. In: Bowden J. Student learning: research into practice The Marysville Symposium, Parkville, Centre for the Study of Higher Education, University of Melbourne 1986

- 72.Stanley I, Al‐Shehri A. Continuing education for general practice 1: experience, competence and the media of self directed learning for established general practitioners. Br J General Practice 199343210–214. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Pearson P, Jones K. Primary care‐opportunities and threats: developing professional knowledge: making primary care research more relevant. BMJ 1997314817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mohanna K, Wall D, Chambers R.Teaching made easy: a manual for health professionals. Abingdon: Radcliffe, 200412

- 75.Lewis L, Elwyn G. Appraisal of family doctors: an evaluation study. Br J General Practice 200353454–460. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bandara I, Calvert G. General practitioners: uncelebrated adult learners – a qualitative study. Education For Primary Care 200213370–378. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Frewin C. The relationship of educational goal setting to the conceptual level model. Annals of 18th Annual Adult Education Research Conference, Minneapolis, Minnesota. 1977 (ERIC/ED138807).

- 78.Flanagan J. The psychologists role in youth's quest for self fulfilment. Annals of 78th Annual Convention of American Psychological Association. Miami Beach, 1970. In: Geis G, Student participation in instruction: student choice. J Higher Educ 197647249–273. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Smith J.The fifth report of the Shipman Inquiry. London: HMSO, 2004, http://www.the‐shipman‐inquiry.org.uk/5r_page.asp?ID = 4814 (Accessed 4 Feb 2006)

- 80.Evans A, Ali S. The effectiveness of personal education plans in continuing professional development: an evaluation, Medical Teacher 20022479–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Carter Y, O'Hara J. Personal development plans: implementing PDPs into general practice. Education for Primary Care 200516672–679. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Nayar V. A qualitative study of general practitioners' views of the appraisal process. Education for Primary Care 200314202–206. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bandara I, Calvert G. General practitioners: uncelebrated adult learners‐ a qualitative study. Education for Primary Care 200213370–378. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Denney M ‐ L. Annual appraisal for general practitioners: where have we got to? Education for Primary Care 200516697–703. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ramsay R, Pitts J. Factors that helped and hindered undertaking professional development plans and personal development plans. Education For Primary Care 200314166–177. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Cervone D. Thinking about self‐efficacy. Behavior Modification 20002430–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Gordon M. A review of the validity and accuracy of self‐assessments in health profession training. Acad Med 199166762–769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ward M, Gruppen L. Research in self assessment: current state of the art. Adv Health Science Educ 2002763–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Shapiro D, Schwartz C. Controlling ourselves, controlling our world: psychology's role in understanding positive and negative consequences of seeking and gaining control. Am Psych 1996511213–1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Eva K, Regehr G. Self‐assessment in the health professions: a reformulation and research agenda. Acad Med 200580S46–S54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Csikszentmihalyi M. If we are so rich, why aren't we happy? Am Psych 199954821–827. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Björk R. Memory and metamemory considerations in the training of human beings. In: Ahimamura A, Metcalfe J, eds. Metacognition: knowing about knowing Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 1994

- 93.Nelson T, Dunlosky J.et al Utilization of metacognitive judgements in the allocation of study during multitrial learning. Psych Science 19945207–213. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Freire P.Education for critical consciousness. New York: Seabury, 1973

- 95.Grant J. Learning needs assessment: assessing the need. BMJ 2002324156–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Davis D, Thomson M. A systematic review of the effect of continuing medical education strategies. JAMA 1995274700–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Asadoorian A, Batty H. An evidence based model for effective self assessment for directing personal learning, J Dent Educ 2005691315–1323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Lyons N. Responsibilities. National Association of Primary Care Educators Newsletter No. 26, Bury 2005

- 99.Searle J, Prideaux D. Medical education research: being strategic. Medical Education 200539544–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Newman P, Peile E. Valuing learners' experience and supporting further growth: educational models to help experienced adult learners in medicine. BMJ 2002325200–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]