Abstract

Cases of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis infection increased in France during the winter of 2004–05 in the absence of epidemiologic links between patients or strains. This increase represents transient amplification of a pathogen endemic to the area and may be related to increased prevalence of the pathogen in rodent reservoirs.

Keywords: Yersinia pseudotuberculosis, disease outbreaks, France, dispatch

Yersinia pseudotuberculosis is an enterobacterial pathogen able to grow at low temperatures. It is widespread in the environment (e.g., water, plants), which is the source of contamination for mammals (especially rodents and their predators) and birds (1,2). Although most cases of human infection are sporadic, outbreaks have occurred in Japan (3,4), Russia (5,6), and Finland (7,8), mainly associated with unchlorinated drinking water or contaminated vegetables. In France, similar increases in case numbers had not been noted until the winter of 2004–05.

The Study

In early January 2005, the French Yersinia National Reference Laboratory (YNRL) received 3 Y. pseudotuberculosis strains isolated by the same laboratory in Dijon over a 1-week period: 2 from fecal samples of 2 children attending the same daycare center and 1 from the blood of a 65-year-old woman. During the same month, 8 additional strains were isolated from persons in other parts of the country by the Yersinia Surveillance Network (based on voluntary participation of 88 hospital-based and private-sector medical laboratories throughout France).

In view of this unusually high number of Y. pseudotuberculosis isolations over a short period, the YNRL alerted France’s national disease surveillance network, the Institut de Veille Sanitaire, which thereafter performed an epidemiologic investigation. In early February, a request was mailed to all member laboratories in the Yersinia Surveillance Network and all 95 microbiology laboratories in university medical centers, asking them to report any recent cases of Y. pseudotuberculosis infection. A reminder letter was mailed to all laboratories that had not replied within 1 month of the initial communication. Moreover, from February through April 2005, a total of 76 general medical center laboratories were contacted by telephone and asked to provide the YNRL with any relevant information and/or isolates. Overall, 27 cases of culture-confirmed Y. pseudotuberculosis infections were spontaneously reported or actively retrieved (Table 1).

Table 1. Relevant characteristics of 27 patients with Yersinia pseudotuberculosis infection, France, winter 2004–05*.

| Age, y | Sex | Risk factors | Main clinical signs/symptoms | Site of organism isolation | O serotype | Illness outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.8 | M | None | Diarrhea | Feces | I | Recovery |

| 1 | M | None | Diarrhea | Feces | III | Recovery |

| 2 | F | None | Diarrhea | Feces | I | Recovery |

| 6 | M | None | Diarrhea | Feces | I | Recovery |

| 9 | F | None | Diarrhea | Feces | I | Recovery |

| 17 | M | Multiple injuries (motorcycle accident) | Postsurgical infection† | Blood | I | Recovery |

| 36 | F | HIV infection | Diarrhea, mesenteric adenitis | Feces | I | Recovery |

| 44 | F | Bone marrow transplantation | Fever | Blood | I | Death |

| 51 | F | Sickle cell anemia, cirrhosis | Diarrhea, esophageal variceal bleeding | Blood | I | Death |

| 59 | M | Cirrhosis | Fever, esophageal variceal bleeding | Blood | I | Recovery |

| 61 | M | Therapeutic aplasia (colorectal cancer) | Fever, abdominal pain | Blood | I | Death |

| 64 | M | Abdominal aortic aneurysm | Abdominal pain | Artery biopsy | I | Recovery |

| 65 | F | Myeloma | Fever, septic shock | Blood | I | Death |

| 70 | M | Cirrhosis | Fever | Blood | I | Recovery |

| 71 | M | Unknown | Abdominal pain | Blood | NA strain | Recovery |

| 71 | M | Diabetes, steroid receipt (for retroperitoneal fibrosis) | Fever, diabetes decompensation | Blood | I | Recovery |

| 72 | M | Kidney transplantation | Fever | Blood | I | Recovery |

| 74 | M | Diabetes | Fever, abdominal pain | Blood | NS | Recovery |

| 75 | M | Viral hepatitis C infection | Fever | Blood | I | Recovery |

| 76 | M | Cirrhosis | Fever | Blood | NS | Recovery |

| 78 | M | Calcific aortic stenosis | Fever, acute heart failure | Blood | I | Recovery |

| 78 | M | Diabetes | Fever, septic shock | Blood and artery biopsy | I | Death |

| 79 | M | Metastatic colorectal cancer | Fever, respiratory distress syndrome | Blood | I | Death |

| 80 | M | Cerebrovascular accident | Fever, cardiogenic shock | Blood | NA strain | Recovery |

| 81 | F | Cirrhosis | Fever | Blood | I | Recovery |

| 82 | M | Diabetes | Fever, septic shock | Blood | NA strain | Death |

| 83 | M | Diabetes | Fever | Blood | I | Recovery |

*NA, nonagglutinable; NS, not sent to Yersinia National Reference Laboratory. †This patient’s signs/symptoms began after hospitalization; all other patients’ signs/symptoms began before hospitalization.

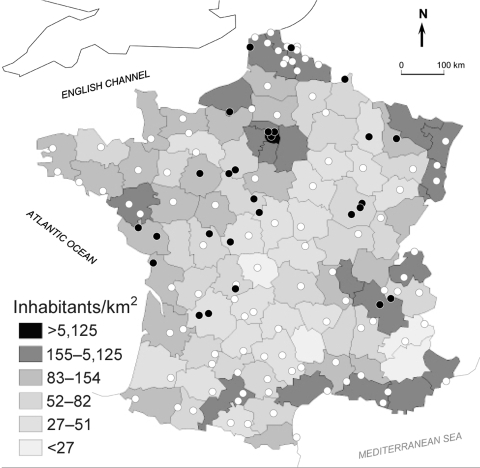

Case reports of Y. pseudotuberculosis infection peaked in January 2005. A food-exposure analysis for the first 10 patients did not identify a potential common food source, so a food survey was not performed for subsequent cases. The pseudotuberculosis cases occurred in 19 different counties throughout France, not necessarily the most populated ones (Figure 1). Data on lifestyle and living conditions were obtained for all but 7 patients, of whom 3 had died and 4 (including 2 children) were lost to follow-up. Of the 22 adults, 13 lived in small towns (<5,000 inhabitants) and 5 lived in rural villages (<500 inhabitants). All but 4 lived in houses, as opposed to apartments. Of the 17 adults whose lifestyle was investigated in detail, 14 had a dog, hunted, gardened, and/or grew their own vegetables. In contrast, all 5 children lived in urban areas (>50,000 inhabitants), compared with only 3 of the 22 adults; 4 of the children lived in apartments.

Figure 1.

Map of France, showing spatial distribution of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis infections during the winter of 2004–05. Black circles, patients' residences; open circles, cities with medical laboratories that stated that they had not isolated any Y. pseudotuberculosis from clinical specimens.

Of the 27 strains isolated, 25 were sent to the YNRL for characterization. All but 4 strains belonged to serotype I, the most common serotype in France. Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis after SpeI digestion of genomic DNA showed that (with the exception of the isolates from the 2 children attending the same daycare center) the DNA fingerprints of the 16 other isolates sent to the YNRL during the peak period were all distinct, even when the strains were isolated from the same county (data not shown).

Conclusions

This episode of increased case numbers differs from episodes reported in the literature by the nationwide distribution of cases, the absence of a locally defined cluster, the genetic diversity of the isolates, the predominance of rural residence for patients, and the dominant clinical presentation of septicemia (3–8). Because the cases were not related to the consumption of a food product sold nationally (e.g., by a supermarket chain), the unknown origin of this phenomenon raises the question of an emerging risk in a new epidemiologic situation.

Of the 27 patients, 19 lived in a strip of land that stretches from northern France to the Atlantic coast and corresponds to the flyways of small migratory birds. Hence, the avian introduction of strains into the country would have been a possible scenario, as has already been suspected for an epizootic of pseudotuberculosis in an American wildlife park (9). Indeed, during the winter of 2004–05, France witnessed a large and unexpected invasion of Bohemian waxwings (Bombycilla garrulus) (10), a species known to migrate from circumpolar areas where pseudotuberculosis is endemic. At that same time, 3 pseudotuberculosis outbreaks were reported in Siberia (11). However, the genetic diversity of the strains isolated from the patients in France and the absence of PCR amplification of the superantigen-encoding gene ypm gene (12) (which is highly prevalent in Far Eastern strains [1]) do not support bird-borne arrival in France of a Y. pseudotuberculosis clone from Russia or the Far East.

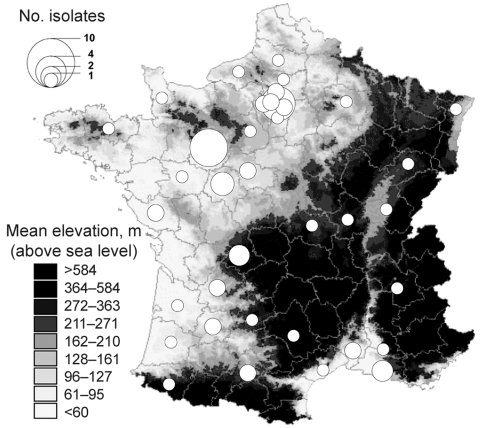

These cases occurred in areas where other human cases of Y. pseudotuberculosis septicemia had been diagnosed (albeit at a much lower rate) in the past 16 years (Figure 2). Exacerbation of a preexisting epidemiologic situation is quite likely. Most previous cases of Y. pseudotuberculosis septicemia also concerned inhabitants of low-altitude plains (Figure 2), mainly in rural areas with extensive agriculture zones, which provide favorable habitats for small mammals. Cases were frequently (27.1%) reported in 5 central-western counties of France, where just 4.6% of the population live and incidence of Francisella tularensis infection (tularemia) is high (27.3%) (www.invs.sante.fr/surveillance/tularemie/donnees.htm). Moreover, 40 cases of tularemia (with incidence peaks in summer and autumn) were reported to the national surveillance system in 2004 (notification of the disease has been obligatory since 2002), whereas only 8 to 19 cases per year had been reported over the preceding and following periods. Like Y. pseudotuberculosis, F. tularensis is known to have a rodent reservoir. Hence, the spatial and temporal correlations between human tularemia and pseudotuberculosis in France over recent years suggest the sudden expansion of a common reservoir in 2004.

Figure 2.

County distribution, France, of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis isolated from human blood and reported to the Yersinia National Reference Laboratory over the 16 years preceding the winter of 2004–05. The number of isolates is represented by proportionally sized circles arbitrarily located at the center of the counties.

Our analysis of the temporal distribution of human Y. pseudotuberculosis septicemia cases over the past 16 years showed a peak every 5 years (Table 2). This finding is reminiscent of human hantavirus infections, which have been linked to cyclical oscillations in the vole population (the virus reservoir). Taken as a whole, these data suggest that a rodent reservoir, mainly in rural areas, could have suddenly increased in the spring of 2004, thus increasing the risk for human transmission of Y. pseudotuberculosis and F. tularensis over the following months.

Table 2. Temporal distribution of receipt ofYersinia pseudotuberculosis blood isolates, France.

| Period | Monthly isolates* |

Annual isolates | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | ||

| 1988–89 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 6 |

| 1989–90 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 7 |

| 1990–91 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 |

| 1991–92 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| 1992–93 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| 1993–94 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| 1994–95 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 8 |

| 1995–96 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 7 |

| 1996–97 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 1997–98 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| 1998–99 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| 1999–00 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| 2000–01 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| 2001–02 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| 2002–03 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| 2003–04 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 8 |

| 2004–05† | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 18 |

| 2005–06 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

4 |

| 1988–2006‡ | 0 | 1 (0.06)§ | 2 (0.12) | 3 (0.18) | 9 (0.53) | 16 (0.94) | 19 (1.12) | 11 (0.65) | 5 (0.29) | 10 (0.59) | 2 (0.12) | 4 (0.24) | 82 (4.82) |

*Received by the French Yersinia National Reference Laboratory since September 1988. To encompass the whole cold season, isolates are presented in 12-month periods from September to August. †Period of increased number of cases. ‡Excludes 2004–05. §Numbers in parentheses are mean monthly value over the 17 years in which case numbers were not increased.

Rodent populations tend to increase with ongoing changes in agricultural practices, e.g., removal of farmland hedges (which provide shelter for the rodents’ predators) and reduction in pesticide use. Hence, the dynamics of the wild rodent population and reduction in pesticide use may represent a useful predictive marker for the occurrence of new outbreaks. The surveillance and control of the small mammal population might help limit the incidence of pseudotuberculosis and other wild rodent–borne diseases of humans in France.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the contributions of A. Goudeau, D. Poisson, L. Bret, R. Sanchez, H. Biessy, M. Weber, J.L. Fauchère, G. Chambreuil, P. Geslin, J.M. Seigneurin, G. Grise, J.C. Reveil, C. Auvray, and C. Recule. We also thank H. Porcheret, A. Secher, A. Marmonier, V. Sivadon, and F. Deyroys du Roure for sending the Y. pseudotuberculosis isolates to YNRL and/or for providing clinical information about patients. We also acknowledge the help of E. Espié and V. Vaillant for food exposure investigations and that of A. Mailles for obtaining national data on human tularemia.

Biography

Dr Vincent, a medical microbiologist at the Lille University Medical Center, is an associate member of the Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale Unité 801 research group on the pathogenesis of Yersinia species. His main research interests are clinical microbiology and the epidemiology of infectious diseases.

Footnotes

Suggested citation for this article: Vincent P, Leclercq A, Martin L, Yersinia Surveillance Network, Duez J-M, Simonet M, et al. Sudden onset of pseudotuberculosis in humans, France, 2004–05. Emerg Infect Dis [serial on the Internet]. 2008 Jul [date cited]. Available from http://www.cdc.gov/EID/content/14/7/1119.htm

References

- 1.Fukushima H, Matsuda Y, Seki R, Tsubokura M, Takeda N, Shubin FN, et al. Geographical heterogeneity between Far Eastern and Western countries in prevalence of the virulence plasmid, the superantigen Yersinia pseudotuberculosis-derived mitogen, and the high-pathogenicity island among Yersinia pseudotuberculosis strains. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39:3541–7. 10.1128/JCM.39.10.3541-3547.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Niskanen T, Waldenstrom J, Fredriksson-Ahomaa M, Olsen B, Korkeala H. virF-positive Yersinia pseudotuberculosis and Yersinia enterocolitica found in migratory birds in Sweden. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2003;69:4670–5. 10.1128/AEM.69.8.4670-4675.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Inoue M, Nakashima H, Ishida T, Tsubokura M. Three outbreaks of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis infection. Zentralbl Bakteriol Mikrobiol Hyg [B]. 1988;186:504–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nakano T, Kawaguchi H, Nakao K, Maruyama T, Kamiya H, Sakurai M. Two outbreaks of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis 5a infection in Japan. Scand J Infect Dis. 1989;21:175–9. 10.3109/00365548909039966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Somov GP, Martinevsky IL. New facts about pseudotuberculosis in the USSR. On the outcome of the first conference on human pseudotuberculosis in the USSR. Contrib Microbiol Immunol. 1973;2:214–6. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smirnova YY, Tebekin AB, Tseneva GY, Rybakova NA, Rybakov DA. Epidemiological features of Yersinia infection in a territory with developed agricultural production. Epinorth 2004. [cited 2005 April 1]. Available from http://www.epinorth.org/artikler/?id=44884

- 7.Jalava K, Hallanvuo S, Nakari UM, Ruutu P, Kela E, Heinasmaki T, et al. Multiple outbreaks of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis infections in Finland. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:2789–91. 10.1128/JCM.42.6.2789-2791.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hallanvuo S, Nuorti P, Nakari UM, Siitonen A. Molecular epidemiology of the five recent outbreaks of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis in Finland. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2003;529:309–12. 10.1007/0-306-48416-1_58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Welsh RD, Ely RW, Holland RJ. Epizootic of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis in a wildlife park. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1992;201:142–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fouarge J, Vandevondele P. Synthesis on the exceptional invasion of waxwings (Bombycilla garrulus) in Europe in 2004–2005 [in French]. Aves. 2005;42:281–311. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yersiniosis—Russia (Siberia). Promed. 2005. Apr 27. Available from http://www.promedmail.org, archive no: 20050427.1169.

- 12.Carnoy C, Floquet S, Marceau M, Sebbane F, Haentjens-Herwegh S, Devalckenaere A, et al. The superantigen gene ypm is located in an unstable chromosomal locus of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis. J Bacteriol. 2002;184:4489–99. 10.1128/JB.184.16.4489-4499.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]