Abstract

To determine the presence of European bat lyssavirus type 1 in southern Spain, we studied 19 colonies of serotine bats (Eptesicus isabellinus), its main reservoir, during 1998–2003. Viral genome and antibodies were detected in healthy bats, which suggests subclinical infection. The different temporal patterns of circulation found in each colony indicate independent endemic circulation.

Keywords: lyssavirus, bats, surveillance, rabies, dispatch

The serotine bat (Eptesicus serotinus) is considered the main reservoir for European bat lyssavirus type 1 (EBLV1). Recently, southern Iberian populations of this species have been classified as E. isabellinus (1), a bat species previously known to exist only in North Africa.

In 1989, 5 EBLV1-infected serotine bats were found dead during a survey of natural colonies in Huelva (Andalusia). The prevalence of EBLV1 antibodies was up to 20% among completely healthy bats that were recaptured 1 year later, providing the first direct evidence of the survival of serotine bats after EBLV1 infection (2). Furthermore, high seroprevalence and presence of viral RNA in the oral cavity and bloodstream of different lyssavirus species have been reported in healthy bats captured in natural colonies in which the numbers of deaths have not increased (3–5), showing direct evidence of subclinical or asymptomatic disease after viral infection. Even viral RNA and antigens have been detected in the brains of healthy captive bats (6). However, reports of experimental lyssavirus transmission have drawn discrepant conclusions (7–9).

The Study

During 1998–2003, a total of 1,030 E. isabellinus from 19 colonies located in the provinces of Huelva, Seville, and Granada (Andalusia), in southern Spain, were sampled. We focused on this region because all EBLV1 cases reported in Spain were from southern Spain. Distances between colonies varied from 0.5 to 317 km.

Bats were captured mainly in so-called maternity colonies made up of adult females and young of both sexes. Each animal was banded and assessed for sex, age, size, and weight. A total of 150 (14.5%) were recaptured. The frequency of repeated captures reached 22.7% in individual bats from 3 colonies that were sampled in all 6 years of the study. All recaptured bats were always found in the same colony in which they were first marked.

Viral RNA was detected in 34 (2.8%) of 1,226 oropharyngeal swab specimens from 33 bats of 8 colonies (1 bat was resampled after a 1-week interval). One bat that tested positive was recaptured and tested negative in a followup sampling effort. Positive results were identified as EBLV1 by direct sequencing as previously described (4,10). Samples for reverse transcription–PCR were stored in a buffer that was designed for RNA preservation but was not suitable for keeping the virus viable for isolation on cell culture.

A total of 626 plasma samples were tested for EBLV1-specific antibodies by using a modification of the rapid fluorescent focus inhibition test (11), but 77 (12.3%) of them were found to be toxic to cells. EBLV1 antibodies were found in 51 (9.3%) of the remaining 549 from 13 colonies. Only 2 of 22 samples showing viral RNA in the oral cavity were antibody positive (Table). Thirteen antibody-positive bats were recaptured in a healthy condition in the following campaigns.

Table. European bat lyssavirus type 1 in Eptesicus isabellinus bats, Spain, 1999–2003*.

| Type of testing | RT-PCR | RFFIT |

|---|---|---|

| Total captures | 1,226 | 626 |

| No. colonies | 19 | 13 |

| Total no. (%) positive |

34 (2.8) |

51 (9.3) |

| 1998 | ||

| No. captures | 164 | 151 |

| No. (%) positive |

4 (2.4) |

10 (6.6) |

| 1999 | ||

| No. (%) captures | 161 | 90 |

| No. positive |

4 (2.5) |

5 (5.6) |

| 2000 | ||

| No. captures | 204 | 128 |

| No. (%) positive |

16 (7.8) |

12 (9.4) |

| 2001 | ||

| No. captures | 209 | 96 |

| No. positive |

0 |

4 (4.2%) |

| 2002 | ||

| No. captures | 287 | 100 |

| No. (%) positive |

10 (3.4) |

5 (5.0) |

| 2003 | ||

| No. captures | 201 | 54 |

| No. positive | 0 | 0 |

*Results obtained during active surveillance. RT-PCR, reverse transcription–PCR, RFFIT, rapid fluorescent focus inhibition test.

The temporal pattern of circulation was completely different in each colony (Appendix Table). Only 1 colony showed continuous circulation from 1998 through 2002.

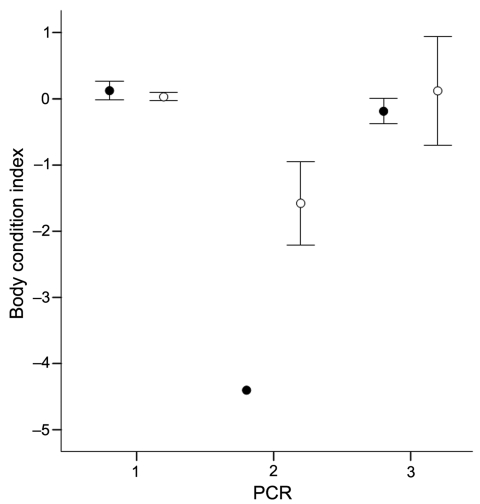

Brains were obtained from 20 bats of the same colony that had been studied previously (4). Differences in body condition between noninfected bats, bats with positive oropharyngeal swabs only, and bats with positive oropharyngeal and brain specimens were tested by an analysis of variance; index of body condition was the dependent variable. Individual body condition was expressed as the residuals from an analysis of covariance with an optimized design, including body mass as dependent variable; forearm length as a covariate; and sex, age, and year as fixed factors. We found a significant negative association (Figure 1) between RNA presence and body condition (F = 11.78; degrees of freedom = 2, 281; p<0.001, n = 292). Post hoc tests indicated that only bats whose brains tested positive had a significantly worse body condition (Tukey honestly significant differences [HSD] test –2.33, p<0.001, and HSD –2.27, p<0.001, respectively). Differences in body condition between oropharyngeal swab–negative and oropharyngeal swab–positive bats were not significant (Tukey HSD 0.57, p = 0.99).

Figure 1.

Relationship between body condition index (mean ± standard error) and diagnosis of European bat lyssavirus type 1 by reverse transcription PCR. Males and females are represented as filled and open circles, respectively. 1, only negative in oropharyngeal swab and brain specimens (● n = 49; ○ n = 225); 2, positive in oropharyngeal swab and brain specimens (● n = 1; ○ n = 4); 3, positive in oropharyngeal swab but negative in brain specimen (● n = 3; ○ n = 4).

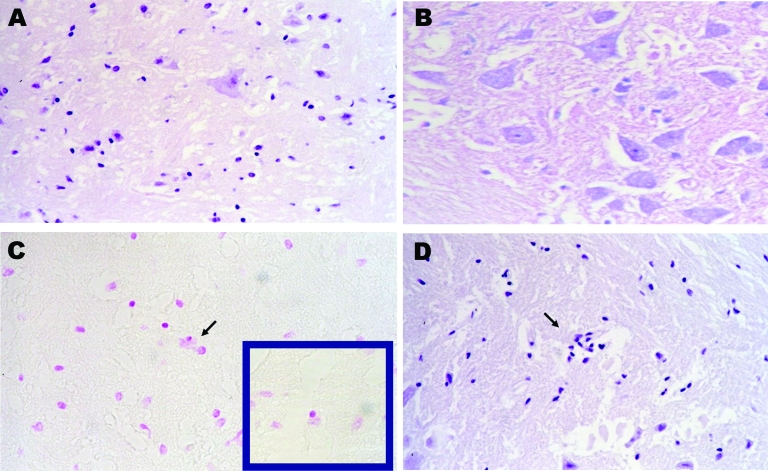

Brain, cerebellum, and spinal cord from 1 bat carcass with natural EBLV1 infection were studied by histopathologic and histochemical techniques. The bat was captured while flying but died during manipulation, which is an extremely rare event. The brain and oropharyngeal swab were positive for EBLV1 by reverse transcription–PCR, and the brain smear was also positive by immunofluorescence. Histopathologic studies showed moderate neuronal degeneration characterized by neuronal hyperchromatosis, chromatolysis, and satellitosis (Figure 2, panel A). The Sellers stain results were negative, proving the absence of Negri bodies (Figure 2, panel B). The occasional presence of basophilic intracytoplasmic structures in neurons located in the cerebral cortex that underwent necrobiosis was interpreted as a neurophagic process that was taking place in the glial cells because these inclusions were shown to be positive by the Feulgen reaction (Figure 2, panel C), whereas the Negri bodies have a strongly acidophilic nature. Moderate gliosis without perivascular infiltration was observed (Figure 2, panel D).

Figure 2.

Pathologic images obtained from a carcass of Eptesicus isabellinus. The bat was captured while flying but died during handling. Brain specimen was positive for lyssavirus antigens by immunofluorescence and for European bat lyssavirus 1 RNA by reverse transcription–PCR. A) Neural degeneration in brain by hematoxylin and eosin stain (H&E); magnification ×400. B) Negative Seller stain in spinal cord indicating the absence of Negri bodies; magnification ×400. C) Positive Feulgen reaction in brain, glial cell neurophagia; magnification ×200. D) Focal proliferation of glial cells by H&E; magnification ×100.

Conclusions

Despite the fact that serotine bats (E. serotinus and E. isabellinus) are the most frequently involved species in cases of bat lyssavirus exposure in humans in Europe, most published surveys of EBLV1 infection in natural bat colonies have focused on other bat species (5,12). Data from serotine bats have been obtained by either serologic or direct detection techniques but not from both (2,4), as in this report.

Our recapture data show an absence of switching among colonies, even between colonies located only a few kilometers apart. This result indicates highly philopatric behavior among female bats, as has been confirmed in a recent mtDNA-based study of these colonies (J. Juste, unpub. data). This could be the cause of the different temporal distribution of the positive results observed in each colony, which suggests a pattern of independent endemic viral circulation different from the model, based on periodic epidemic waves of fast viral spreading proposed for the mouse-eared bat (Myotis myotis) (12).

The analysis of body condition index as a measure of physiologic condition gives additional evidence for mild or subclinical infection in the previously described long-term survival of EBLV1 RNA or antibody-positive bats (2,4,5,12). Similar body condition values between bats with oropharyngeal swabs that were positive for the virus and those that were negative could be interpreted as a recent virus infection for which no symptoms have developed. However, 1 lyssavirus-positive bat showed no viral RNA 3 years later. One bat even showed RNA in the oral cavity in consecutive samples separated by 1 week. Our findings suggest that asymptomatic EBLV1 RNA carriage may be common in serotine bats (2–5,9,13,14). In only a small subset of them does symptomatic neurologic infection progress to more severe body condition. However, most of these bats were captured while they were flying, and only 1 of those involved in an episode of human exposure had lost the ability to fly. This bat had the poorest body condition. The absence of Negri bodies and the moderate percentage of nerve cells affected found in the bat, captured while flying, suggest a subclinical process, as has been proposed for EBLV1 in Rousettus aegyptiacus (6,14). We cannot predict whether severe encephalitis was about to develop in these bats. The lack of pathogenicity could have arisen through long-standing coevolution between bats and viruses, as the phylogenetic data suggest (15). Nevertheless, additional work is necessary to establish whether the presence of EBLV1 RNA in the oral cavity is associated with the excretion of live virus.

In a similar study of M. daubentonii in the United Kingdom, only EBLV2 antibodies, but not viral RNA in the oropharyngeal cavity, were reported (3). Another study of the experimental transmission of Aravan, Khujand, and Irkut viruses to E. fuscus found oral excretion only in bats whose conditions were progressing to neurologic infection and death (8). These facts suggest differences between models of pathogenesis of lyssavirus infections in bats.

In summary, our findings indicate that natural maternity colonies of E. isabellinus behave as close communities in which EBLV1 independently circulates, which suggests an endemic pattern associated with asymptomatic or mild disease. Further studies are needed to 1) investigate the circumstances under which neurologic manifestations develop in bats (which lead to the abnormal behavior usually associated with human exposures) and 2) to establish the epidemiologic implications for public health of asymptomatic oral RNA carriage. The anthropophilic behavior of this bat species makes active surveillance highly recommended to predict risk factors that allow taking political decisions relating to public health.

Supplementary Material

Number of European bat lyssavirus type 1-positive results for each colony of Eptesicus isabellinus bats (in gray fields), Spain.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge Juan L. García-Mudarra, José A. Garrido, Elena Migens, Joaquín Muñoz, Juan Quetglas, Jesús Nogueras, and Carlos Ruiz for providing technical assistance as bat handlers. We also thank the Genomic Unit of the National Center of Microbiology for analyzing the genomic sequences. We also gratefully acknowledge Thomas Müller who kindly donated the specific monoclonal antibody W239 used in this work.

This project was financially supported by grants from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (MPY 1364/99, MPY 1271/01, and EXP 03/0020), by an agreement between the Public Health Department of the Spanish Ministry of Health and the Instituto de Salud Carlos III for the development of “Improvement rabies surveillance in Spain through the development of molecular tools and the establishment of a new system for active rabies surveillance,” by the Spanish program of Research in Biomedicine (FIS 98/0945), by the WP5 of the European Med-Vet-Net network of excellence, by the project SAF 2006-12784-C02-01/ of the General Research Program of the Spanish Ministry of Science and Education, and by the Environmental Delegation of Seville. This research has been approved by the appropriate animal review board of the Spanish Society for Conservation and Study of Bats.

Biography

Ms Vázquez-Morón is a doctoral candidate in science at the Complutense University of Madrid and a microbiologist who is developing a new system for active rabies surveillance at the Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Madrid. Her research interests include emergent viruses in bats and their public health implications.

Footnotes

Suggested citation for this article: Vázquez-Morón S, Juste J, Ibáñez C, Ruiz-Villamor E, Avellón A, Vera M, Echevarría JE. Circulation of European bat lyssavirus type 1 in endemic serotine bats, Spain. Emerg Infect Dis [serial on the Internet]. 2008 Aug [date cited]. Available from http://www.cdc.gov/EID/content/14/8/1263.htm

References

- 1.Ibanez C, Garcia-Mudarra JL, Ruedi M, Stadelmann B. The Iberian contribution to cryptic diversity in European bats. Acta Chiropt. 2006;8:277–97. 10.3161/1733-5329(2006)8[277:TICTCD]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Perez-Jorda JL, Ibanez C, Munoz-Cervera M, Tellez A. Lyssavirus in Eptesicus serotinus (Chiroptera: Vespertilionidae). J Wildl Dis. 1995;31:372–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brookes SM, Aegerter JN, Smith GC, Healy DM, Jolliffe TA, Swift SM, et al. European bat lyssavirus in Scottish bats. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11:572–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Echevarria JE, Avellon A, Juste J, Vera M, Ibanez C. Screening of active lyssavirus infection in wild bat populations by viral RNA detection on oropharyngeal swabs. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39:3678–83. 10.1128/JCM.39.10.3678-3683.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Serra-Cobo J, Amengual B, Abellan C, Bourhy H. European bat lyssavirus infection in Spanish bat populations. Emerg Infect Dis. 2002;8:413–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ronsholt L, Sorensen KJ, Bruschke CJ, Wellenberg GJ, van Oirschot JT, Johnstone P, et al. Clinically silent rabies infection in (zoo) bats. Vet Rec. 1998;142:519–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shankar V, Bowen RA, Davis AD, Rupprecht CE, O'Shea TJ. Rabies in a captive colony of big brown bats (Eptesicus fuscus). J Wildl Dis. 2004;40:403–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hughes GJ, Kuzmin IV, Schmitz A, Blanton J, Manangan J, Murphy S, et al. Experimental infection of big brown bats (Eptesicus fuscus) with Eurasian bat lyssaviruses Aravan, Khujand, and Irkut virus. Arch Virol. 2006;151:2021–35. 10.1007/s00705-005-0785-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aguilar-Setien A, Loza-Rubio E, Salas-Rojas M, Brisseau N, Cliquet F, Pastoret PP, et al. Salivary excretion of rabies virus by healthy vampire bats. Epidemiol Infect. 2005;133:517–22. 10.1017/S0950268805003705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vázquez-Morón S, Avellón A, Echevarria JE. RT-PCR for detection of all seven genotypes of Lyssavirus genus. J Virol Methods. 2006;135:281–7. 10.1016/j.jviromet.2006.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meslin F-X, Kaplan MM, Koprowski H. A rapid fluorescent focus inhibition test (RFFIT) for determining rabies virus-neutralizing antibody. In: Meslin F-X, Kaplan MM, Koprowski H, editors. Laboratory techniques in rabies. 4th edition. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Amengual B, Bourhy H, Lopez-Roig M, Serra-Cobo J. Temporal dynamics of European bat Lyssavirus type 1 and survival of Myotis myotis bats in natural colonies. PLoS One. 2007;2:e566. 10.1371/journal.pone.0000566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Steece R, Altenbach JS. Prevalence of rabies specific antibodies in the Mexican free-tailed bat (Tadarida brasiliensis mexicana) at Lava Cave, New Mexico. J Wildl Dis. 1989;25:490–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wellenberg GJ, Audry L, Ronsholt L, van der Poel WH, Bruschke CJ, Bourhy H. Presence of European bat lyssavirus RNAs in apparently healthy Rousettus aegyptiacus bats. Arch Virol. 2002;147:349–61. 10.1007/s705-002-8324-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hughes GJ, Orciari LA, Rupprecht CE. Evolutionary timescale of rabies virus adaptation to North American bats inferred from the substitution rate of the nucleoprotein gene. J Gen Virol. 2005;86:1467–74. 10.1099/vir.0.80710-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Number of European bat lyssavirus type 1-positive results for each colony of Eptesicus isabellinus bats (in gray fields), Spain.