Abstract

There has been growing interest in conducting community-based health research using a participatory approach that involves the active collaboration of academic and community partners to address community-level health concerns. Project EXPORT (Excellence in Partnerships, Outreach, Research, and Training) is a National Center for Minority Health and Health Disparities (NCMHD) initiative focused on understanding and eliminating health disparities for racial and ethnic minorities and medically underserved populations in the United States. The New York University (NYU) Center for the Study of Asian American Health (CSAAH) is 1 of 76 Project EXPORT sites. This paper describes how CSAAH developed partnerships with varied Asian American community stakeholders as a first step in establishing itself as a Project EXPORT center that uses community-based participatory research (CBPR) as its orienting framework. Three guiding principles were followed to develop community–academic partnerships: (1) creating and sustaining multiple partnerships; (2) promoting equity in partnerships; and (3) commitment to action and research. We discuss strategies and action steps taken to put each principle into practice, as well as the successes and challenges we faced in doing so. Developing community–academic partnerships has been essential in our ability to conduct health disparities research in Asian American communities. Approaches and lessons learned from our experience can be applied to other communities conducing health disparities research.

Keywords: Community-Based Participatory Research, Health disparities, Asian Americans, immigrants, minorities

The last two decades have seen a growing interest in conducting community-based health research using a participatory approach that involves the active collaboration of academic and community partners to address community-level health concerns. Many academic institutions now have university entities devoted to promoting health partnership research.1,2 Given the increased recognition of health partnerships’ potential impact on promoting community health3 and increased federal interest in promoting academic–community partnerships,4–6 university entities are at the forefront of ensuring that CBPR is conducted according to a core set of established principles.

PROJECT EXPORT CENTERS

Established in 2002, Project EXPORT is a NCMHD initiative focused on understanding and eliminating health disparities for racial and ethnic minority and medically underserved populations in the United States.7 The NYU CSAAH is 1 of 76 Project EXPORT sites. Project EXPORT requires that academic institutions actively collaborate with community-based partners to address and reduce health disparities.

The funding of CSAAH as a Project EXPORT center formalized a long-standing relationship among the NYU School of Medicine and several community partners that promote health research and access in underserved Asian American communities across the New York City metropolitan area. CSAAH and its community partners were interested in conducting Asian American health disparities research using a CBPR framework. In New York City, there are considerable cultural variations among Asian American ethnic groups, as well as political dynamics among the community-based organizations (CBOs) that serve them. Moreover, there is great fragmentation among the Asian American population in New York City and few pan-Asian CBOs that address the various needs of different Asian ethnic groups. Rather, each ethnic group relies on their ethnic-specific CBOs for information, programs, and services.8 Thus, to facilitate CSAAH’s ability to conduct health disparities research with different Asian ethnic populations using a CBPR framework, it was critical to nurture existing relationships and create new relationships with community partners serving New York City’s varied Asian American communities.

This paper describes how CSAAH developed partnerships with varied Asian American community stakeholders as a first step in establishing itself as a Project EXPORT center that uses CBPR as its orienting framework. As more academic research institutions develop community-based research projects requiring active community participation, we believe our experience at CSAAH can serve as a guide to establishing and developing these academic–community relationships. We solicited the review of a CSAAH community partner who is a long-standing advocate of the Asian American community and has considerable knowledge of community dynamics in New York City to provide input on points that should be emphasized, including which examples best illustrated the specific accomplishments of the academic–community partnership described in the manuscript.

GUIDING PRINCIPLES USED TO DEVELOP ACADEMIC–COMMUNITY PARTNERSHIPS

Three key principles guided CSAAH’s relationship building with community partners serving the New York City Asian American community: (1) creating and sustaining multiple partnerships; (2) promoting equity in partnerships; and (3) commitment to action as well as research.

Creating and Sustaining Multiple Partnerships

A central tenet of CBPR is to develop and engage multiple partnerships and perspectives in the research process.1,4,9 Underlying this tenet is the notion that, through active collaboration, the skills, knowledge, and expertise of various community stakeholders can be incorporated to effectively define health challenges, their causal factors, and their solutions.3,4 Accordingly, one of CSAAH’s guiding principles was to create and sustain partnerships with multiple CBOs serving New York City’s Asian American community. CSAAH employed three specific strategies related to this principle.

Development of Community-Based Ethnic Coalitions and Pan-Ethnic Advisory Groups

CSAAH developed community-based ethnic-based coalitions and pan-ethnic advisory groups to address health issues in multiple Asian American ethnic groups (e.g., Filipino American, Vietnamese American). Table 1 describes the three action steps taken to implement this strategy, the relevance of each action step, and examples of strategy accomplishments.

Table 1.

Strategies and Action Steps Related to Creating and Sustaining Multiple Partnerships

| Guiding Principle: Creating and Sustaining Multiple Partnerships | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Strategies | Action Steps | Relevance | Examples of Strategy Accomplishments |

| 1. Development of community-based ethnic and panethnic coalitions. |

|

|

|

| 2. Demonstrating CSAAH’s support, involvement, and dedication to local events in the Asian American community. |

|

|

|

| 3. Formalizing relationships with CBOs. |

|

|

|

The first action step was to recruit health and non-health organizations to ensure multidisciplinary coalitions. Because many first- and second-generation Asian Americans seek health information from non-health organizations,8 it was imperative to recruit non-health organizations for CSAAH’s coalitions and advisory boards. Moreover, non-health organizations provided CSAAH with an understanding of the social, economic, and cultural context that place Asian American immigrants at risk for certain diseases and illnesses. CSAAH’s coalitions include organizations ranging from health care agencies (e.g., community clinic), workers’ rights organizations (e.g., domestic workers’ union), faith-based organization (e.g., mosque), and advocacy groups (e.g., Asian children’s welfare organization). The second action step was to recruit and support collaborations with organizations that represent specific Asian ethnic groups, pan-Asian interests, and other racial/ethnic groups. This ensured that CSAAH’s work was sensitive to the needs of particular ethnic groups, but also addressed cross-cutting issues that affect all Asian groups as well as other minority populations. For example, in 2004 CSAAH convened an advisory committee to guide the development of its annual Asian American Health conference. The committee includes representation from 15 different health care, business, social service, advocacy, academic, and CBOs. The committee has been instrumental in ensuring that the conference content represents various Asian ethnic groups, other minority groups, and special populations; diverse sectors; and the multitude of health issues that these communities face. The third action step was to develop operational norms, guidelines, and bylaws for each coalition. This step facilitated the process of consensus building and communication between and among coalition members. It clearly defined for all partners their roles and the process by which coalition members worked with each other. It also formalized the mechanisms to determine accountability for accomplishing specific coalition activities and goals. For example, the Kalusugan Coalition, a Filipino health coalition that consists of representatives from CSAAH and several Filipino CBOs, engaged in an intensive, 2-year-long process of coalition training and development led by experienced facilitators to establish norms, guidelines, and bylaws for the group (e.g., establishing guiding principles for the coalition such as “health is a right for all”).

Demonstrating CSAAH’s Support, Involvement, and Dedication to Local Events in the Asian American Community

The second strategy was to demonstrate CSAAH’s support, involvement, and dedication to local events and activities in New York City’s Asian American population. Three specific action steps were taken to implement this strategy (Table 1). First, CSAAH staff joined and/or participated in the activities of various local and national organizations and, when possible, joined their advisory or executive boards. By participating in Asian American CBOs’ activities and various boards, CSAAH enhanced its responsiveness to these CBOs’ needs. In addition, CSAAH staff have been elected to the boards of local and national organizations that do not directly represent Asian American communities, which ensures that the promotion of Asian American needs and issues in settings where this community might otherwise go unnoticed or Asian voices and perspectives may be absent. In fact, several CSAAH staff are currently the only Asian American board member of several local and national organizations. Second, CSAAH staff attended as many outreach events as possible sponsored by CBOs that targeted specific Asian ethnic groups. Third, CSAAH often co-sponsored health and outreach events with CBOs. For example, CSAAH has co-sponsored events such as health fairs serving the South Asian community, forums addressing health issues in the Filipino community, community gatherings in the Vietnamese community, several conferences and symposia in the Chinese community, and national pan-Asian events such as the National Asian and Pacific Islander HIV/AID Awareness Day. Together, these last two action steps demonstrated CSAAH’s support for these CBOs’ activities and served as a public relations tool to familiarize CBOs and community members with CSAAH. In addition, our involvement in such events allowed for the sharing and dissemination of community-based research and programs activities before diverse forums.

Formalizing relationships with CBOs

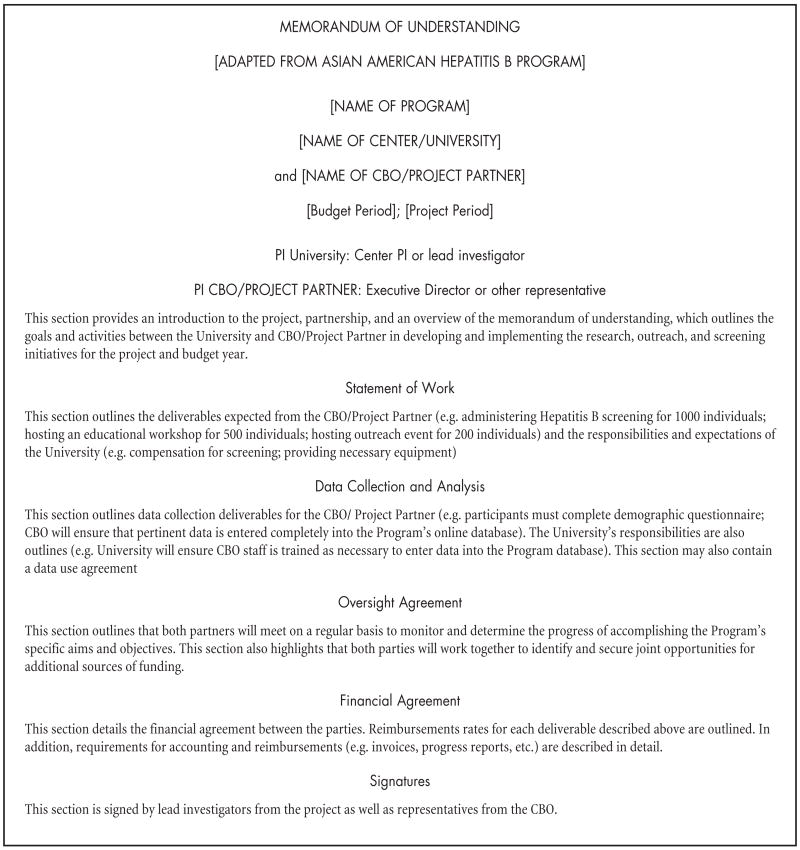

The third strategy was to formalize relationships with CBOs, which was achieved with two action steps. First, research projects were submitted for funding and letters of support were created that delineated the roles, responsibilities, and activities of academic and community partners. CSAAH engaged in meetings that involved all potential partners and a series of one-on-one meetings with individual partners to ensure that each partner had an opportunity to describe their expectations for working on a project, as well as the needed capacity to participate in the project. Second, for grants that were funded, CSAAH and community partners jointly developed Memorandums of Understanding (MOUs) that formalized the roles, responsibilities, and activities of academic and community partners, as outlined in the letters of support submitted with grant applications. The MOUs also delineated who was accountable for specific tasks and activities, as well as for the overall project. Figure 1 contains a sample MOU that was created between CSAAH and community partners for the Asian American Hepatitis B Program, a project funded by the New York City Council that is a partnership between CSAAH and several community-based organizations and health care agencies. Finally, not all CSAAH projects are associated with a particular grant or funding mechanism. In these situations, CSAAH engaged in one-on-one meetings to clarify roles and responsibilities of each partner. For example, CSAAH’s Vietnamese Community Health Initiative developed a relationship with CAAAV—Organizing Asian Communities, a Bronx community-based organization, to conduct a needs assessment in the Southeast Asian population. Meetings were held with partners to understand each partner’s strengths and contributions. These meetings helped to clarify CSAAH’s role (technical assistance provider for research design and analysis) and the CBO’s role (providing leadership on mobilizing and conducting outreach and survey administration with community). Together, these three steps were important in demonstrating mutual understanding, respect, and reciprocity between CSAAH and its community partners, and establishing processes and norms for different types of academic–community collaborations.

Figure 1.

components of sample memorandum of understanding

Promoting Equity Among CSAAH and Community Partners

Israel et al.1 note that “building equitable and collaborative partnerships … takes time and commitment on the part of all partners to foster participation and shared decision making.” As such, CSAAH implemented two main strategies to promote equity among CSAAH and its community partners (Table 2).

Table 2.

Strategies and Action Steps Related to Promoting Equity in Partnershipss

| Guiding Principle: Promoting Equity in Partnerships | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Strategies | Action Steps | Relevance | Examples of Strategy Accomplishments |

| 1. Ameliorating negative stereotypes regarding the relationship between community and academic partners. |

|

|

|

| 2. Establishing equity with partners on development, implementation, and evaluation of new projects. |

|

|

|

| 3. Formalizing relationships with CBOs. |

|

|

|

Ameliorating Negative Stereotypes Regarding the Relationship Between Community and Academic Partners

The first strategy was to ameliorate negative stereotypes regarding the relationship between community and academic partners. Historically, the needs of immigrants and minorities have not been addressed by many academic institutions, and often those academic researchers working with minority and immigrant populations gave little value to community partners’ contributions.4,10 Consequently, research was conducted with the notion that academic researchers possessed superior knowledge of communities’ needs and strategies to address disparities in health status and/or access to services. To address these negative stereotypes, CSAAH implemented three specific action steps.

First, CSAAH prioritized recruitment of staff with diverse and extensive experience working in Asian American communities who reflected the communities served by CSAAH. We wanted to ensure that staff not only understood the social, cultural, and health issues salient to addressing disparities in health status and access for Asian Americans, but had a demonstrated history of diverse forms of community research, health advocacy, and community organizing in the Asian American community. Recruiting culturally diverse staff assisted in bridging cultural differences among Asian ethnic groups as well as among staff, faculty members, and community stakeholders. Currently, CSAAH has eight full-time staff members from Chinese, Vietnamese, South Asian, and Filipino backgrounds. The staff composition is a mixture of first- and second-generation immigrants and refugees. All staff members have a history of working with local Asian organizations, and have been able to bring these relationships with them and broaden CSAAH’s partnership base by recruiting these organizations into CSAAH’s coalitions. In addition, CSAAH has worked with over 50 students and interns from diverse ethnic and racial backgrounds. Second, efforts were made to educate NYU faculty and CSAAH staff on the importance of eliciting community partners’ experiences and skills. For example, CSAAH staff are members of NYU School of Medicine’s Deans Council on Institutional Diversity, where they promote the importance of community engagement. Their efforts have directly resulted in the establishment of an Institute of Community Health and Research, which has an explicit aim of promoting CBPR. Third, CSAAH encouraged faculty, staff, and interns to attend events, lectures, and trainings that promote an understanding of cultural competency, CBPR, and Asian American health issues. These last two action steps helped to increase NYU faculty and CSAAH staff members’ understanding of community partners’ roles and importance in a research study, as well as their understanding of CBPR principles and how CSAAH aimed to use these principles in its work.

Establishing Equity With Partners on Development, Implementation, and Evaluation of New Research Projects

The second strategy to promote equity among CSAAH and community partners was to establish equity on the development, implementation, and evaluation of new research grants and projects. To achieve this strategy, we undertook two action steps.

First, we ensured that partners had an equal role in developing new grants and projects, including establishing the project priorities and research methodologies. By engaging partners at the beginning to ensure their buy-in and ownership of a research project, we have been successful in maintaining the active participation of community partners throughout several CBPR projects CSAAH and its community partners have initiated. Second, we negotiated distribution of research funds depending on the roles and responsibilities by CSAAH and community partners. Because each partner helped develop research priorities and methods, they gained a greater appreciation for resources they would need to implement outreach, training, and/or research activities. For example, CSAAH worked with the Charles B. Wang Community Health Center (CBWCHC) to develop the Health Disparities Research Training Program (HDRTP). The HDRTP was funded as part of CSAAH’s original P60 application to NCMHD. After receiving the award, CSAAH engaged in discussions with CBWCHC and realized that prior subcontract amounts agreed upon would not be sufficient for CBWCHC to carry out the work; for this reason, CSAAH increased the subcontract amount to the organization. Finally, a core CBPR principle is to promote a co-learning process.4 In our work, community partners received education and training on grant writing, budgeting, and research design. As a result, they are able to more confidently and accurately estimate the funding they would need to implement research activities. For example, seminars on research design were held for community partners of Project AsPIRE, a community health worker intervention funded by NCMHD designed to address cardiovascular disease in the Filipino community.

Commitment to Action and Research

A key feature of CBPR is its promotion of research and action on the part of academic and community partners.4 CSAAH employed two strategies to promote this principle (Table 3).

Table 3.

Strategies and Action Steps Related to Commitment to Action and Research

| Guiding Principle: Commitment to Action and Research | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Strategies | Action Steps | Relevance | Examples of Strategy Accomplishments |

| 1. Creating a strong working relationship with ethnic media. |

|

|

|

| 2. Advocating on behalf of Asian American health issues. |

|

|

|

| 3. Formalizing relationships with CBOs. |

|

|

|

Creating a Strong Working Relationship With the Ethnic Media

The first strategy was to create a strong working relationship with ethnic media. To do this, we engaged in two action steps. First, CSAAH encouraged ethnic media to attend CSAAH outreach, education, and training events and to publicize these events in local and ethnic newspapers because newspapers are the most widely utilized media vehicle among New York City’s Asian American population. By engaging the media, we were able to publicize CSAAH events and activities before and after each event. In addition to having media cover CSAAH events, we have invited media representatives to participate in panel discussions at conferences and symposia to highlight the role of media in health promotion. For example, CSAAH co-hosted a symposium on heart disease in the Chinese community in which representatives from Chinese local and national media participated in an interactive panel. Second, CSAAH worked with the media to highlight Asian American health issues on television and radio programs and in local and national ethnic and mainstream newspapers. Since 2003, CSAAH has been responsible for over 100 news stories on health issues affecting Asian American communities. This has included articles in the local Chinese, Filipino, Korean, South Asian, and Vietnamese papers; radio spots on the local Chinese radio; and front page coverage in The New York Times.

Advocating on Behalf of Asian American Health Issues

The second strategy was to advocate on behalf of Asian American health issues. This strategy involved three action steps. First, CSAAH encouraged locally elected officials to attend CSAAH events, recognizing them for their support to the Asian American community and educating them on Asian American health issues. CSAAH also sought letters of support from these elected officials to demonstrate political support of newly proposed initiatives. Second, CSAAH helped to mobilize community partners to advocate for funding on specific health disparities issues. The importance of this step was to demonstrate unity and leadership within the Asian American community about their health priorities and needs. In addition, this step raised awareness of issues facing the Asian American community among legislators and politicians. Third, CSAAH worked with local and national legislators on behalf of Asian American communities. By doing so, CSAAH wanted to translate meaningful research findings into relevant health policies for Asian American communities. For example, the identification of hepatitis B and liver cancer as priority health disparity issues in the Asian American community led to mobilizing community and political leaders around the issue of hepatitis B prevention, screening, and treatment. CSAAH, in collaboration with its community partners, secured several million dollars from New York City Offices of City Council to prevent and treat hepatitis B and to conduct research on the epidemiology of hepatitis B and risk factors for liver cancer. In addition, a CSAAH senior investigator is a member of the National Taskforce on Hepatitis B Focus on Asian/Pacific Islander Americans, which, in 2006, worked closely with Representative Mike Honda (D, Calif) to introduce a bill to promote and support Hepatitis B research, education, outreach, vaccination, and treatment.

LESSONS LEARNED

Using the strategies and action steps described, CSAAH has been able to achieve numerous positive outcomes. Success has been measured by the degree to which CSAAH has expanded its infrastructure to conduct partnership-based health disparities research in the Asian American community. As such, CSAAH has expanded its partnership base to more than 40 CBOs; recruited and employed a diverse group of eight full-time staff and over 50 interns and volunteers; established health-related coalitions and advisory boards in the Chinese, Filipino, Korean, South Asian, and Vietnamese communities; conducted needs assessments in these communities; received media coverage in over 100 news vehicles; received several small foundation grants; and received two large research grants—one from the Offices of the New York City Council, and one from the National Institutes of Health (Tables 1–3). However, we have also encountered several challenges to implementing the strategies and action steps listed. The following section describes challenges and the lessons learned related to engaging academic and community partners in research and action emanating from CSAAH.

Challenges with Academic Partners

A major challenge for both faculty and senior staff is clarifying the distinction between community-based research and CBPR. Despite CSAAH’s efforts to clarify this distinction and provide training on CBPR, the idea of fully incorporating the input of community partners with respect to developing research priorities, methods, and dissemination strategies was novel to many faculty. For these faculty, there were doubts that community partners could significantly contribute to developing a scientifically sound research protocol. In addition, some faculty continued to believe that their work was CBPR if they worked with community partners after a research protocol was established. There was concern that the research process would be extremely time and labor intensive if too much emphasis was placed on building consensus on a research protocol among community partners who may have limited research experience.

Challenges with Community and Other Partners

We also experienced challenges to implementing the strategies and action steps described earlier with CSAAH’s community partners. First, there were significant community dynamics that needed to be worked through and addressed. Before Project EXPORT funding, CSAAH primarily collaborated with public hospitals and health care providers serving low-income and uninsured Asian American communities. These community partners had had a long history of serving the health care needs of the Asian American community and considered themselves as the “experts” within the community on how to address Asian American health disparities. Some of these organizations did not stress the need to create new research or health partnerships with smaller organizations, organizations serving marginalized ethnic groups within the Asian American population, and/or organizations primarily providing social or non-health services. Although CSAAH respected each of these organizations for their expertise in the communities they served, it was clear that CSAAH needed to reach out to a diverse group of stakeholders. Such diversity was essential to addressing health disparities from both a pan-Asian and ethnic-specific perspective that was culturally and linguistically sensitive to both the social and health needs of the Asian American population.

CONCLUSION

CSAAH believes that the principles we have utilized to guide our development of community–academic partnerships can be adapted by other initiatives working with various immigrant and minority communities. In fact, we are currently working with other New York-based Project EXPORT Centers to develop cross-cultural initiatives that will allow us to determine evidence-based strategies for reducing racial and ethnic disparities. We feel that the core principles we have adhered to—creating and sustaining multiple partnerships, promoting equity in partnerships, and promoting action as well as research—are essential in conducting health disparities research in all communities.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the following individuals for their support of the NYU Center for the Study of Asian American Health: All CSAAH staff, interns, and volunteers; members of the Executive Planning Committee, including William Bateman, MD; Jyotsna Changrani, MD, MPH; Henry Chung, MD; Sun Hoo Foo, MD; George Friedman-Jimenez; Francesca Gany, MD, MS; Kenny Kwong, PhD; Henry Pollack, MD; Thomas Tsang, MD, MPH; Arnold Stern, MD, PhD; and Tung-Tien Sun, PhD. The authors also wish to acknowledge the following individuals for their helpful comments in the review of this manuscript: Marguerite Ro, DrPH; Simona Kwon, DrPH; Ruchel Ramos, MPA; and Suki Terada Ports.

The authors are grateful for the collaboration of our community, academic, and clinical partners who are involved in the following projects and coalitions: the Asian American Hepatitis B Program Coalition; Center for the Study of Asian American Health Conference Planning Committee; Health Disparities Research Training Program; Kalusugan Coalition; Project AsPIRE; South Asian Health Initiative; and the Vietnamese Community Health Initiative.

This publication was made possible by Grant Numbers P60 MD000538 and R24MD001786 from NIH NCMHD and its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH NCMHD.

References

- 1.Israel BA, Parker EA, Rowe Z, Salvatore A, Minkler M, Lopez L, et al. Community-based participatory research: Lessons learned from the Centers for Children’s Environmental Health and Disease Prevention Research. Environ Health Perspect. 2005 Oct;113:1463–71. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Higgins DL, Metzler M. Implementing community-based participatory research centers in diverse urban settings. J Urban Health Bull N Y Acad Med. 2001;78:488–94. doi: 10.1093/jurban/78.3.488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Israel B, Schulz A, Parker E, Becker A. Review of community-based research: Assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annu Rev Public Health. 1998;19:173–202. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Minkler M, Wallerstein N, editors. Community based participatory research for health. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality [homepage on the Internet] Rockville, MD: The Agency; [updated July 2002]. Community-Based Participatory Research. Conference Summary. Available from: http://www.ahrq.gov/about/cpcr/cbpr/ [Google Scholar]

- 6.Viswanathan M, Ammerman A, Eng E, Gartlehner G, Lohr KN, Griffith D, et al. RTI University of North Carolina Evidence-based Practice Center. Evidence report/technology assessment no. 99. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2004. Community-based participatory research: Assessing the evidence. AHRQ Publication: 04-E022-2. Contract No.: 290-02-0016. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ncmhd.nih.gov [homepage on the Internet] Bethesda: National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities; c2000–2001; Available from: http://ncmhd.nih.gov/ [Google Scholar]

- 8.Foner N, editor. New immigrants in New York. New York: Columbia University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parker E, Israel B, Williams M, Brakefield-Caldwell W, Lewis T, Robins T, et al. Community action against asthma: Examining the partnership process of a community-based participatory research project. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18:558–67. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.20322.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hatch J, Moss N, Saran A, Presley-Cantrell L, Mallory C. Community research: Partnership in Black communities. Am J Prev Med. 1993;9( Suppl):27–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]