Abstract

Aim:

Recently, attempts have been made to develop cognitive-behaviour therapy (CBT) treatment models to target negative symptoms in individuals with schizophrenia, as well as individuals at ultra-high risk (UHR) for psychosis. Successful CBT treatment is founded on active patient participation including completion of homework assignments such as daily logs of activities and experiences. However, these very negative symptoms may themselves hinder the rate of homework assignment completion. We describe a case report of using experience sampling method with a Palm computer as an adjunct to CBT with a female patient at UHR status with predominantly negative symptoms. Our aim was to assess the feasibility and effectiveness of this methodology to improve homework completion and overcome treatment barriers associated with negative symptoms.

Methods:

Over the course of treatment, the patient was provided with a Palm computer to carry with her throughout her daily activities. The Palm computer was pre-programmed to beep randomly 10 times per day (10 a.m.–12 a.m.) over each three-day assessment period to elicit information on daily functioning.

Results:

The use of the Palm computer was acceptable to the patient and resulted in a substantial increase in homework completion. This methodology resulted in rich information about the patients' daily functioning and patterns of improvement during treatment. The experience sampling method data were also successfully used in the application of treatment interventions.

Conclusion:

The findings support the feasibility and effectiveness of using Palm computers as adjunct to CBT with UHR individuals with predominantly negative symptoms. The implications for treatment and future research directions are discussed.

Keywords: cognitive-behaviour therapy, experience sampling method, negative symptoms, palm computer, psychosis prodrome

The use of cognitive-behaviour therapy (CBT) to treat individuals with schizophrenia has expanded dramatically over the past two decades. Initial case reports of successful treatments led to numerous randomized clinical trials supporting the use of CBT in this population.1-3 Recent studies have also provided promising results of the use of CBT to treat individuals at ultra-high risk (UHR) for psychosis.4-7 Successful CBT treatment is founded on active patient participation including completion of homework assignments such as daily logs of mood, thoughts and behaviours. This view has been underscored by Rush,8 who stated that homework assignments are crucial to treatment success. They help the patient ‘(i) develop objectivity about situations that are otherwise stereotypically misconstrued; (ii) identifies underlying assumptions; and (iii) develops and tests alternative conceptualizations and guiding assumptions’ (p. 110). In addition, homework assignments extend patients' exposure time to therapeutic material beyond the time spent in the session and allows them to ‘practise’ what was learned in therapy.8 Empirical findings support this view: Burns and Spangler9 demonstrated that the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) dropped on average 4.35 points for every unit of homework completion. Similar results have also been reported by a number of other authors.10,11

While the focus of CBT with individuals with schizophrenia has been primarily on targeting positive psychotic symptoms, recently, attempts have been made to apply CBT to improve negative symptoms.12 This new focus may be in part due to the growing recognition of the link between negative symptoms and poor functioning in schizophrenia.13 However, these very negative symptoms, the target of treatment, may themselves hinder the effectiveness of CBT. Among patients with schizophrenia, several barriers to CBT homework completion have been identified including avolition, ineffective decision-making, social withdrawal, distractibility and difficulties initiating activities.14-16 These barriers, along with difficulties in memory and executive functioning, represent some of the core features of schizophrenia. Thus, these negative symptoms and cognitive impairments, which are also commonly present in individuals at UHR for psychosis,17,18 present unique challenges for treatment success.

The use of electronic devices such as Palm computers to administer homework assignments offers a number of advantages that may be particularly useful as part of CBT with individuals who display negative symptoms or cognitive difficulties: first, the use of palm computers as part of real-time, real-world (in vivo, in situ) daily functioning avoids the retrospective recall associated with standard, paper-based, daily homework logs – a feature that may be particularly important given the memory difficulties experienced by many individuals with schizophrenia and UHR status.19,20 Second, given the prevalence of avolition in these populations, the ability to preprogramme the Palm computers to sound alarms to prompt patients to complete homework assignments may be a useful feature. Delespaul21 described a number of case reports in which completion of (paper-based) daily logs was triggered using programmable wristwatches as part of a successful psychotherapy with individuals with schizophrenia-spectrum disorders. Third, in comparison with standard paper-and-pencil tasks, Palm computers can provide a direct time-stamp measure of homework compliance including precise homework completion times. This feature may increase therapists' confidence that the homework assignment was actually completed in a timely manner (rather than just prior to the session). Finally, Palm computers offer an easier method to customize questionnaires and incorporate branching – that is, presentation of different questions based on the subjects' responses to previous items.

Currently, there are no published reports about the use of Palm computers as an adjunct to CBT with individuals with schizophrenia or who are at UHR for psychosis. We describe a case report of using a Palm computer as an adjunct to CBT with a UHR patient with high IQ and intact insight, whose negative symptoms, although predominant, have not yet coalesced. Our primary aims were to assess the feasibility of this methodology to augment homework completion and overcome the treatment barriers associated with negative symptoms and cognitive difficulties. In particular, we were interested in whether the use of a Palm computer would increase the completion rate of daily logs of mood, thoughts, symptoms and social contexts.

METHOD

Patient information

Andrea is a 20-year-old single woman who was referred for treatment at a clinical research programme (Center of Prevention and Evolution (COPE)) in New York for individuals at UHR for developing psychosis. Andrea's medical and psychiatric histories are notable for obsessive–compulsive symptoms starting at age 11, including preoccupation with germs, leading to frequent hand washing. These symptoms resolved without treatment at age 13. Despite these difficulties, Andrea excelled in school – she attended a magnet high school (designed for gifted students and typically offering advanced courses), graduated with a 3.8 Grade Point Average, and went on to attend a competitive university.

In college, Andrea's grades were in the B to C range during freshman year, but deteriorated to the D range the following year. During this time, Andrea increasingly spent more and more time by herself in her dormitory room. Although she never had many friends, during this period she withdrew from the few friendships she had managed to establish in college. Andrea reported experiencing increased anxiety and depressed mood, which led her to stop attending classes: ‘it was such an effort’. She eventually had to take a medical leave from school and sought treatment. Andrea was referred to a psychiatrist and presented with depressive symptoms including depressed mood, anhedonia, hypersomnia, poor appetite, low energy, guilt about being on medical leave, hopelessness, helplessness and passive suicidal ideation. Over time, she was prescribed a number of medications including Wellbutrin XL, Effexor, Remeron, Zoloft and Clomipramine – all with minimal benefit. She also attended psychodynamically oriented psychotherapy for about a year, which she found to be somewhat helpful, although her symptoms did not remit.

At admission to the COPE clinical research programme, Andrea presented with symptoms of depression and anxiety, as well as prominent negative symptoms including considerable avolition, anhedonia, blunted affect and notable latency of response. She reported that she had no social contacts. Aside from working part-time at a fast food restaurant, Andrea's activities centred on ‘surfing’ the Internet for 6–7 hours per night, which resulted in a reversal of her sleep–wake schedule. Andrea also endorsed a number of attenuated psychotic symptoms, including feeling that someone was watching her, beliefs that she might have a halo, as well as worries about seeing dead bodies on the side of the road. These symptoms did not achieve delusional severity. Andrea was determined to be at UHR for psychosis based on the Structured Interview for Prodromal Syndromes and Scale of Prodromal Symptoms (SIPS/SOPS).22 Her total symptom scores were as follows: positive symptoms = 17 (range 0–30), negative symptoms = 22 (range 0–36), disorganization symptoms = 9 (range 0–24) and general symptoms = 15 (range 0–24). Consistent with her competitive academic background, Andrea performed exceptionally well on the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Test – 3rd edition (FIQ = 142, VIQ = 138, PIQ = 136). However, further neuropsychological testing indicated a pattern of performance consistent with Dysexecutive Syndrome, with particular difficulties in organizing problem solving approaches, monitoring progress and adjusting cognitive processes to situational demands. Andrea denied any current substance use (corroborated by a toxicology screen), but reported trying marijuana once. She also admitted to previous use of alcohol approximately two to three times per week, 1 year earlier. Endocrine laboratory results were within normal limits. A magnetic resonance imaging revealed a slight asymmetry in her pituitary gland, but was otherwise within normal limits.

Treatment

Andrea started individual CBT to address her difficulties. She endorsed a number of broad goals including returning to school from medical leave, increasing social activities and having more hobbies. Specific stressors included fear of walking home at night from work and seeing dead bodies on the side of the road, as well as completing common daily activities (e.g. registration for school, getting a haircut etc.). She also endorsed difficulty in getting out of bed in the morning and frequent lateness to work. Andrea reported that her primary strategy to deal with stressors was avoidance. Initial work focused on developing rapport, familiarizing Andrea with the CBT treatment framework and exploring the phenomenology of her symptoms. Andrea proved to be a poor historian of her experiences. A number of attempts to use standard, paper-based homework assignments to ascertain daily moods and activities were unsuccessful because of Andrea not remembering to complete the tasks, as well as her difficulties organizing her responses (at best, only 3 days completed each week). Repeated attempts to simplify the homework tasks to include just one daily entry did not increase homework compliance or its quality.

Palm computer assessment procedure

Andrea was provided with a Palm Tungsten T3 handheld computer to carry with her throughout her daily activities. She was given a brief introduction session in which basic operations of the Palm computer were discussed and demonstrated. We used experience sampling method (ESM) with a Palm computer to present questions and to collect responses about momentary ratings of mood, cognition, behaviour as well as social context. ESM is an ecologically valid time-sampling of self-reports developed to study the dynamic process of person–environment interactions.21 Kimhy and colleagues23 have previously demonstrated the feasibility and validity of using ESM with Palm computers to collect information about cognition, mood, behaviour and social context as part of daily functioning in a research protocol of hospitalized individuals with schizophrenia. Other authors have demonstrated the feasibility and validity of this methodology as part of a study of middle-age and older individuals with schizophrenia living in the community.24 The feasibility of using Palm computers as an adjunct to CBT in an outpatient setting has been successfully demonstrated previously in treatment of individuals with panic disorder, general anxiety disorder and social phobia.25-27

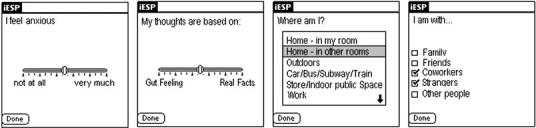

The homework assignments were for 3 days and were conducted during weekdays. Accordingly, the Palm computer was preprogrammed to beep randomly 10 times per day (between 10 a.m.–12 a.m.) over a 3-day period to elicit information about current thoughts, mood, behaviour and social context. Upon hearing the Palm's beep, Andrea was instructed to respond to the questions presented on the screen (e.g. ‘I feel sad/depressed’). For each symptom/mood question, Andrea was asked to indicate on the Palm computer's screen the quality of her current experience on a graphical slider similar to a visual analogue scale (from ‘not at all’ to ‘very much’; see Fig. 1). Responses were represented in the output as a value between 1 (‘not at all’; leftmost extreme) and 100 (‘very much’; rightmost extreme). Additionally, she was asked about her current social context and activities (i.e. ‘Where am I?’; ‘I am with Ω ?’; see Fig. 1). As part of her CBT treatment, Andrea was also trained to evaluate her thoughts and feelings, and attribute the degree to which they were based on ‘gut feelings’ versus factual reality (see Fig. 1). To minimize the potential of memory bias influencing the experiences reported, Andrea was given 180 seconds to respond to the activating beeps and to each of the questions. If she did not complete her response within this time period, the Palm computer was programmed to automatically turn off until the next activation.

FIGURE 1.

Screen shots of sample questions presented on the Palm computer.

To minimize the potential of the Palm computer interfering with Andrea's normal daily activities and possibly impacting her responses, the Palm computer was preprogrammed to be locked between responses to prevent access to other Palm functions (calendars, to-do lists etc.) and previous responses. The locking procedure also ensured the privacy and confidentiality of Andrea's responses. For safety reasons, Andrea was instructed not to respond to questionnaires while driving. The Palm computer was collected from Andrea during the next weekly treatment session, and the data were downloaded to a PC.

RESULTS

The use of a Palm computer to complete momentary logs of mood, thoughts, behaviour and social context was highly acceptable to Andrea, as evident by her own report as well as the number of experience samples completed. Out of possible 30 experience samples during each of the homework assignments, Andrea completed 19, 18 and 21 experience samples respectively (60–70%; see Table 1), and entered some data on each day during which she carried the Palm. By contrast, earlier attempts in therapy to utilize homework assignments using paper-based daily mood/activity logs (one entry per day) were returned only partially completed. At most, Andrea completed only three mood/activity entries over a period of week. In addition, the availability of precise time-stamps of the entries allowed increased confidence that the questions were indeed completed in a timely matter (i.e. not retrospectively). Some missed experience samples (five during the month 5 assessment) were due to not being able to use the Palm computer during work. Others were missed because of taking a nap or talking on the phone. The rich information obtained via the Palm computer provided a unique and detailed perspective of Andrea's daily thoughts, moods and experiences, as well as her progress during therapy.

TABLE 1.

Changes in Andrea's average scores on items assessing activities, cognition, mood and context over the course of treatment

| Month of treatment | Admission | Month 3 | Month 5 | Month 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BDI-II total score | 37 | 35 | 31 | 17 | |

| % of experience samples completed | – | 63 | 60 | 70 | |

| ESM activities and context (% of time) | Social context: being ‘alone’ | – | 100 | 100 | 90 |

| Activity: doing ‘nothing’ | – | 32 | 20 | 16 | |

| Activity: ‘surfing the Internet’ | – | 37 | 13 | 16 | |

| Location: ‘my room’ | – | 100 | 100 | 90 | |

| ESM cognition (average) | ‘I feel competent doing this activity’ (for anticipated activity) | – | 56 | 61 | 64 |

| ‘I prefer doing something else’ | – | 68 | 52 | 46 | |

| ‘My thoughts are difficult to express’ | – | 45 | 22 | 17 | |

| ‘My thoughts are based on:’ gut feeling (1) → real facts (100) | – | 39 | 48 | 56 | |

| ‘My future looks:’ bleak (1) → promising (100) | – | 26 | 29 | 35 | |

| ESM mood (average) | ‘I feel depressed/sad’ | – | 54 | 56 | 43 |

| ‘I feel guilt’ | – | 53 | 44 | 39 | |

| ‘I feel anxious’ | – | 54 | 45 | 40 | |

| ‘I feel lonely’ | – | 67 | 65 | 68 | |

| SIPS/SOPS | Positive symptoms | 17 | 8 | 8 | – |

| Negative symptoms | 22 | 16 | 14 | – | |

| Disorganization symptoms | 9 | 6 | 4 | – | |

| General symptoms | 15 | 14 | 13 | – | |

ESM cognition and mood ratings are based on a visual slider similar to a visual analogue scale. Responses ranged from 1 (leftmost extreme, ‘not at all’) to 100 (rightmost extreme, ‘very much’).

BDI-II, Beck Depression Inventory; ESM, experience sampling method; SIPS/SOPS, Structured Interview for Prodromal Syndromes and Scale of Prodromal Symptoms.

For each homework assignment, we calculated the average score of Andrea's ratings for the items assessing cognition, mood, behaviour and social context. The data from the homework assignments during months 3, 5 and 8 of treatment are presented in Table 1. These data were augmented by clinical ratings completed as part of research assessments at the COPE programme. Inspection of the data indicates a number of trends over the course of treatment:

Changes in activities: during the assessment in month 3, Andrea's activities consisted primarily of ‘surfing’ the Internet or ‘doing nothing’. However, over the course of treatment, her activities appeared to become more diversified. At the same time, she continued to spend the great majority of her time at home alone in her room.

Changes in mood: Andrea reported reductions in her experience of anxiety, guilt and depression/sadness. However, her experience of loneliness remained unchanged, consistent with her spending the majority of her time alone in her room.

Changes in cognition: as treatment progressed, Andrea reported fewer difficulties expressing her thoughts, as well as an increased ability to recognize dysfunctional thoughts. Additionally, she reported being more interested in her own activities with a greater sense of her own competency. She also appeared to be more hopeful about her future.

The changes in Andrea's thoughts, mood and functioning were also reflected in her parallel ‘standard’ symptom assessments. Her BDI-II score decreased from 37 (admission) to 17 (month 8). Although the attenuated psychotic symptoms were not a central focus of the treatment, her SIPS/SOPS ratings of positive symptoms also declined from 17 to 8 between admission and month 5 (month 8 ratings were unavailable). Similarly, her negative symptoms and disorganized symptoms declined from 22 to 14 and from 9 to 4 respectively.

In addition to providing information about Andrea's progress in treatment, the Palm computer data were also used as part of treatment. For example, information about Andrea's expected versus actual competency in doing activities across the day was compared, revealing her tendency to underestimate the degree to which she anticipated to be competent doing activities in the next hour versus her actual experiences. This information was presented to Andrea about 4 months into the treatment using a figure (see Fig. 2). The presentation of the figure served as a powerful example of ‘real-world’ actual cognition and behaviour, and it was used to elicit hypothetical explanations about this discrepancy. These collaborative discussions led to further joint exploration of Andrea's cognitive biases and the nature of her dysfunctional expectations. In the following therapy sessions, the conversation expanded to metacognitive processes in general and ways in which to apply her newly acquired insight to a broader range of situations and activities. Grant and Beck28 have highlighted the central role of dysfunctional (defeatist) beliefs in mediating the link between negative symptoms and impairment in functioning in individuals with schizophrenia.

FIGURE 2.

Andrea's average ratings of her current versus anticipated competency doing activities across time of day during month 3′s assessment.

DISCUSSION

The present case report is the first to describe the utilization of a Palm computer as an adjunct to CBT with a patient at UHR of psychosis. Overall, the obtained data, as well as Andrea's own report of its acceptability to her, suggest that the use of the Palm computer to complete daily logs of thoughts, mood, behaviour and social context resulted in a substantial increase in the completion rate of logs. In contrast to the partial responses obtained using the standard (paper-based) logs, Andrea completed 60–70% of the computerized experience samples as part of a relatively demanding schedule, and did it over several homework assignments. This pattern of responses suggests that the integration of Palm computers during CBT of individuals at UHR for psychosis may have the potential to increase patients' compliance with homework assignments, and thus contribute to treatment effectiveness. In addition, the availability of precise time-stamps by the Palm computer provided increased confidence that the data were actually collected as part of daily functioning in the real world (rather than completed just prior to the treatment session).

The information obtained via the Palm computer about changes in thoughts, mood, behaviour and social contexts over the course of treatment was consistent with Andrea's symptomatic improvement as measured by the BDI and SIPS/SOPS, suggesting the reported data have face validity. The Palm computer data allowed a unique perspective on Andrea's progress in therapy. The data point to her reduced feelings of depression/sadness, guilt and anxiety. While she continued to spend the majority of her time by herself in her room and feel lonely, her activities became more diversified. Of note, her difficulties expressing her thoughts were reduced substantially as treatment progressed (average: 45→17), suggesting a potential mechanism by which CBT may lead to symptomatic improvements.

Andrea's responses were consistent with data we have previously collected from schizophrenia inpatients and healthy controls.23 A number of the questions presented to Andrea were identical to those used as part of that study. Her answers to these questions provide a context for her ratings and clinical status. For example, by the third month of treatment, Andrea had an average score of 54 on depression/sadness compared with 47 and 11 among the schizophrenia patients and healthy controls respectively. Similarly, she appeared to experience a profound sense of loneliness (average = 67), even more so than that expressed by schizophrenia inpatients (average = 35) and healthy controls (average = 10). Her difficulties in expressing her thoughts diminished between the third and eighth months (45→17) of treatment to a level intermediate between that of schizophrenia inpatients and healthy controls (28 and 9 respectively). Similarly, her disinterest in activities (‘I prefer doing something else’) declined from 68 in the third month to 47 in the eighth month, which was more at par with the ratings of both schizophrenia inpatients and healthy controls (47 and 41 respectively). Overall, these ratings suggest that in some domains of cognition and mood, Andrea's experiences in the third month of treatment were consistent with those of hospitalized schizophrenia patients.

The use of Palm computers or similar electronic devices (e.g. programmable mobile phones or instant messaging devices) to collect information about individuals' experiences may be particularly valuable with individuals at UHR for psychosis. This high-risk period, which occurs typically during late adolescence and early adulthood, may prove an opportune time for the use of Palm computers in CBT, as insight remains relatively intact and cognition is not as impaired. In addition, the popularity of such electronic devices among adolescents and young adults may make their use particularly appealing to individuals in this age group, facilitating their integration as part of CBT treatment. The use of Palm computers may also be feasible with individuals with schizophrenia – studies by our group and others have demonstrated the efficacy and validity of this methodology in collecting information about thoughts, mood, behaviour and social context.23,24 In addition to helping with memory problems or difficulties initiating tasks in this population, the use of Palm computers may offer additional benefits. For example, the opportunity to successfully use a technologically advanced, sophisticated electronic device over several days may be by itself a positive experience. Verbal feedback from participants in our research studies with hospitalized schizophrenia patients23 supports this view, as a number of patients viewed the use of the Palm computer as a confidence-building experience. For example, during debriefing after that study, one patient with schizophrenia commented that his observation of other people using Palm computers and his own ability to operate it as part of the study ‘made me feel normal’.

While the focus of using a Palm computer with ESM in the present treatment was to augment homework compliance as part of CBT, the versatility of Palm computers makes it feasible to develop software that would allow more complex homework assignments. Such assignments could include interactive communications that will allow increased flexibility in responding to patient's answers, as well as more sophisticated and detailed behavioural activations that will augment clinical material discussed and exercised during face-to-face therapy sessions. For example, in response to stressful experiences, the Palm computer may be used to offer patients to practise relaxation breathing exercises or remind them to look for different explanations for their experiences. Such software is currently under development.

Limitations of the present paper should be acknowledged. First, the present paper is a case report of CBT with a UHR individual – the findings need to be replicated in a larger sample. Future investigations should also assess the use of Palm computers as part of CBT with individuals with schizophrenia. Second, this was a patient with particularly high IQ – it is unclear whether the use of Palm computers as adjunct to CBT would work in UHR patients who have more average intelligence. Third, lack of motivation (avolition) has important implications for success in CBT. While Andrea displayed negative symptoms, including avolition, she seemed to have difficulties more with self-initiation of activities than with actually completing them once she started working. Thus, the use of the Palm computer in her case appears to have been particularly useful as it helped her initiate homework tasks. It is possible that the use of Palm computers may be less effective in patients in which avolition may involve both difficulties in initiation and persistence at completing tasks. Future studies should aim to clarify this potential distinction. Similarly, Andrea's lack of disorganization might have facilitated her use of, and engagement with, the technology. Such successful integration may not be feasible with more disorganized patients.

In summary, the present case report is the first to describe the utilization of a Palm computer as an adjunct to CBT with a patient at UHR of psychosis. The findings suggest that Palm computers may be integrated successfully as an adjunct to CBT with this population as well as potentially with individuals with schizophrenia. In particular, Palm computers may be useful in enhancing homework compliance and increasing therapist confidence in data validity.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Judy Thompson, PhD, Marina Shikhman, PhD, and Samantha Breen for their help in the preparation of this paper.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wykes T, Steel C, Everitt B, et al. Cognitive behavior therapy for schizophrenia: effect sizes, clinical models, and methodological rigor. Schizophr Bull. 2008;34:15. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbm114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pilling S, Bebbington P, Kuipers E, et al. Psychological treatments in schizophrenia: I. Meta-analysis of family intervention and cognitive behaviour therapy. Psychol Med. 2002;32:763–82. doi: 10.1017/s0033291702005895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rector NA, Beck AT. Cognitive behavioral therapy for schizophrenia: an empirical review. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2001;189:278–87. doi: 10.1097/00005053-200105000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morrison AP, French P, Walford L, et al. Cognitive therapy for the prevention of psychosis in people at ultra-high risk: randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;185:291–7. doi: 10.1192/bjp.185.4.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morrison AP, French P, Parker S, et al. Three-year follow-up of a randomized controlled trial of cognitive therapy for the prevention of psychosis in people at ultrahigh risk. Schizophr Bull. 2007;33:682–7. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbl042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.French P, Shryane N, Bentall RP, Lewis SW, Morrison AP. Effects of cognitive therapy on the longitudinal development of psychotic experiences in people at high risk of developing psychosis. Br J Psychiatry. 2007 doi: 10.1192/bjp.191.51.s82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bechdolf A, Ruhrmann S, Wagner M, et al. Interventions in the initial prodromal states of psychosis in Germany: concept and recruitment. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 2005;48:s45–48. doi: 10.1192/bjp.187.48.s45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rush AJ. Cognitive therapy of depression: rationale, techniques, and efficacy. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1983;6:105–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burns DD, Spangler DL. Does psychotherapy homework lead to improvements in depression in cognitive-behavioral therapy or does improvement lead to increased homework compliance? J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68:46–56. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.1.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Persons JB, Silberschatz G. Are results of randomized controlled trials useful to psychotherapists? J Consult Clin Psychol. 1998;66:126–35. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.1.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bryant RA, Sackville T, Dang ST, et al. Treating acute stress disorder: an evaluation of cognitive behavior therapy and supportive counseling techniques. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:1780–6. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.11.1780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rector NA, Beck AT, Stolar N. The negative symptoms of schizophrenia: a cognitive perspective. Can J Psychiatry. 2005;50:247–57. doi: 10.1177/070674370505000503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Milev P, Ho BC, Arndt S, et al. Predictive values of neurocognition and negative symptoms on functional outcome in schizophrenia: a longitudinal first-episode study with 7-year follow-up. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:495–506. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.3.495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rector NA. Homework use in cognitive therapy for psychosis: a case formulation approach. Cogn Behav Pract. 2007;10:2. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dunn H, Morrison AP, Bentall RP. Patients' experiences of homework tasks in cognitive behavioural therapy for psychosis: a qualitative analysis. Clin Psychol & Psychother. 2006;9:361–9. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dunn H, Morrison AP, Bentall RP. The Relationship between patient suitability, therapeutic alliance, homework compliance and outcome in cognitive therapy for psychosis. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2006;13:145–52. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lencz T, Smith CW, Auther A, et al. Nonspecific and attenuated negative symptoms in patients at clinical high-risk for schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2004;68:37–48. doi: 10.1016/S0920-9964(03)00214-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hawkins KA, Addington J, Keefe RS, et al. Neuropsychological status of subjects at high risk for a first episode of psychosis. Schizophr Res. 2004;67:115–22. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2003.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eastvold AD, Heaton RK, Cadenhead KS. Neurocognitive deficits in the (putative) prodrome and first episode of psychosis. Schizophr Res. 2007;93:266–77. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Simon AE, Cattapan-Ludewig K, Zmilacher S, et al. Cognitive functioning in the schizophrenia prodrome. Schizophr Bull. 2007;33:761–71. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbm018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Delespaul P. Assessing Schizophrenia in Daily Life. ISPER; Maastricht, the Netherlands: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miller TJ, McGlashan TH, Rosen JL, et al. Prodromal assessment with the structured interview for prodromal syndromes and the scale of prodromal symptoms: predictive validity, interrater reliability, and training to reliability. Schizophr Bull. 2003;29:703–15. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a007040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kimhy D, Delespaul P, Corcoran C, et al. Computerized experience sampling method (ESMc): assessing feasibility and validity among individuals with schizophrenia. J Psychiatr Res. 2006;40:221–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2005.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Granholm E, Loh C, Swendsen J. Feasibility and validity of computerized ecological momentary assessment in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2008;34:7. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbm113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Newman MG, Kenardy J, Herman S, et al. Comparison of palmtop-computer-assisted brief cognitive-behavioral treatment to cognitive-behavioral treatment for panic disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1997;65:178–83. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.1.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Newman MG, Consoli AJ, Taylor CB. A palmtop computer program for the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder. Behav Modif. 1999;23:597–619. doi: 10.1177/0145445599234005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Przeworski A, Newman MG. Palmtop computer-assisted group therapy for social phobia. J Clin Psychol. 2004;60:179–88. doi: 10.1002/jclp.10246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grant PM, Beck AT. Defeatist beliefs as a mediator of cognitive impairment, negative symptoms, and functioning in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn008. doi: 10.1093 (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]