Summary

The Bcr-abl kinase inhibitor STI571 produces clinical responses in most patients with Chronic Myeloid Leukemia (CML); however, development of resistance limits utility. One strategy to overcome STI571 resistance is to decrease the level/activity of Bcr-abl. We reported that disruption of the anti-apoptotic protein Survivin promoted STI571-induced apoptosis in Bcr-abl+ K562 cells, through caspase-dependent Bcr-abl degradation. To investigate the utility of Survivin disruption in drug-resistant CML cells, we generated STI571-resistant K562 cells by long-term culture with STI571. In contrast to parental cells, where Survivin disruption enhances STI571-induced apoptosis, Survivin disruption in STI571-resistant cells failed to promote STI571-induced apoptosis; rather it protected cells from STI571 and other apoptosis-inducing compounds. Even though Survivin levels were similar in parental and STI571-resistant K562 cells, Survivin disruption in STI571-resistant cells increased telomerase activity, likely due to Bcr-abl/c-abl degradation. Our results indicate that emergence of STI571 resistance in Bcr-abl+ K562 cells results from induction of additional pathways that circumvent STI571-responsiveness.

Keywords: Survivin, Telomerase, Apoptosis, Leukemia

I. Introduction

The Bcr-abl oncogene, encodes a cytoplasmic protein with constitutive tyrosine kinase activity and is found in cells of ~95% of CML patients (Kurzrock et al, 1988; Sawyers, 1999). The specific Bcr-abl inhibitor, STI571 (Gleevec®, imatinib mesylate), produces clinical responses in most patients with CML (Druker et al, 2001); however, the development of resistance (Hochhaus et al, 2001) has prompted the search for alternative treatments. The mechanisms of clinical resistance to STI571 can involve increased Bcr-abl through gene amplification (Gorre and Sawyers, 2002) or mutations in the Bcr-abl catalytic domain that interfere with STI571 binding (Shah et al, 2002). One possible strategy to overcome STI571 resistance would be to decrease Bcr-abl levels.

Survivin blocks apoptosis by inhibiting caspases 3, 7 and 9 (Ambrosini et al, 1997; Shin et al, 2001; Pennati et al, 2004). We recently reported that Bcr-abl up regulates Survivin transcription and that Survivin disruption promotes STI571-induced apoptosis by disrupting mitochondrial membrane potential resulting in cytochrome-c release and caspase-dependent Bcr-abl degradation (Wang et al, 2005). Caspase-dependent degradation of Bcr-abl oncoprotein in cells in which Survivin expression is disrupted may represent a pathway to enforce apoptosis in STI571-resistant cells. Since enhanced degradation of Bcr-abl should reduce its antiapoptotic effects, we investigated Survivin knockdown as a strategy to treat drug resistance to STI571. Using STI571-resistant K562 cells, we found that Survivin disruption did not promote STI571-induced apoptosis as seen in parental K562 cells, rather, it produced the opposite effect. Reduced apoptosis upon Survivin disruption in STI571-resistant K562 cells was accompanied by elevated telomerase activity associated with increased Bcr-abl/c-abl degradation. Our results suggest that development of STI571 resistance in K562 cells occurs through effects on multiple pathways, indicating that combined drug interventions will likely be necessary to overcome STI571 resistance.

II. Material and Methods

A. Reagents and antibodies

Recombinant IL-3 and anti-human Survivin (AF886) were purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). Anti-c-abl (Ab-3) was from Oncogene (LaJolla, CA). Hemin and CDDP (Cisplatin) were purchased from Sigma Chemical Company (St. Louis, MO). Anti-hTERT and anti-actin antibodies were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). STI571 (Gleevec) was obtained from Novartis Inc (Basel, Switzerland). The caspase 3-specific inhibitor Z-DEVD-FMK was from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA).

B. Cell lines, plasmids and transfection

Human K562 cells, which express Bcr-abl, and MCF7 breast cancer cells were maintained in RPMI-1640 with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (HI-FBS) (Hyclone Sterile Systems, Logan, UT) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. STI571-resistant cells were generated by stepwise culture with increasing concentration of STI571 (0.05–0.5 μM) over 6 months. Survivin and antisense-Survivin (reverse orientation) constructs were cloned in the IRES-EGFP-MIEG3 vector as described (Wang et al, 2004). Transfection of K562 cells was carried out as reported previously (Wang et al, 2005). Briefly, log phase K562 cells plus 30 μg of Survivin plasmid DNAs were mixed in a Bio-Rad gene Pulser Cuvette and incubated at 37°C for 15 minutes. Following one pulse electroporation (360V, 960 F), cells were incubated at 37°C for 15 minutes and resuspended in RPMI-1640 + 10% HI-FBS. After 48 hours, GFP+ cells were isolated by FACS (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA), expanded for one week and resorted for GFP+ cells. IL-3-dependent murine Ba/F3 cells were maintained in RPMI-1640 with 10% HI-FBS, 1% penicillin-streptomycin and 0.1 ng/mL rmIL-3. Construction of Ba/F3 cells stably expressing bicistronic retrovirus MIEG3 plasmids containing full-length or antisense mouse Survivin and transient transfection of MCF7 with full-length or antisense human Survivin were described previously (Wang et al, 2004).

C. Protein extraction and Western analysis

Whole cell lysates for Western analysis were prepared in 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), 10 μg/ml phenylmethyl sulfonyl fluoride, and 1 mM sodium orthovanadate. Aliquots were kept on ice for 30 minutes and centrifuged at 14,000×g for 30 minutes. Protein concentrations were determined using the Bio-Rad protein assay kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Fifty micrograms of protein was denatured in 2X SDS buffer at 95°C for 5 minutes, separated by electrophoresis on 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gels (SDS-PAGE) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes. The filters were incubated with specific antibodies followed by horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse or anti-rabbit immunoglobulin and developed by electrogenerated chemiluminescence (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ).

D. Flow cytometry analysis for apoptosis

Apoptosis was quantitated based on hypodiploid DNA content or Annexin-V binding as previously described (Wang et al, 2004). Cell apoptosis was analyzed using a FACScan and CellQuest software (BD Bioseinces).

E. Telomerase activity and telomere length assay

Telomerase activity and telomere length were analyzed using the Telo TAGGG Telomerase PCR ELISA and Telo TAGGG Telomere Length Assay kits (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

III. Results

A. Disruption of Survivin in STI571-resistant K562 cells fails to promote STI571-induced apoptosis

We previously showed that Survivin disruption in K562 cells enhances STI571-induced apoptosis, accompanied by cytochrome-c release, disruption of mitochondrial membrane potential, and caspase-mediated Bcr-abl protein cleavage, suggesting that Survivin knockdown might overcome drug resistance to STI571 (Wang et al, 2005).

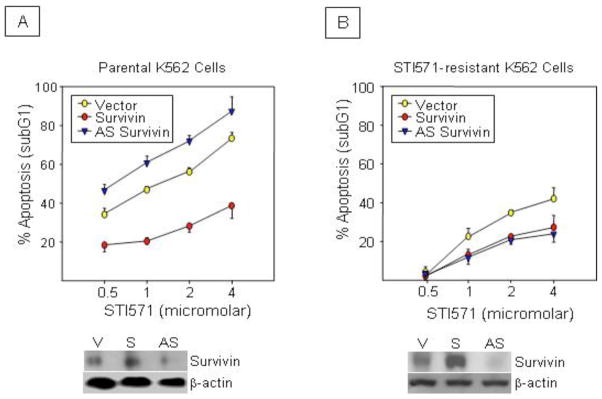

STI571-resistant K562 cells were generated by culture of cells with increasing concentrations of STI571 (0.05 to 0.5 μM) over 6 months. Resistant K562 cells were significantly less sensitive to STI571 than parental cells (Figures 1A and 1B). To knockdown Survivin protein, parental and STI571-resistant K562 cells were transfected with retrovirus containing an antisense Survivin construct. Cells were also transfected with empty vector and wild-type Survivin as controls. Western blot analysis validated Survivin knockdown and over expression, respectively (Figure 1A and 1B, Western inserts). Westerns also demonstrated that STI571-resistant cells contained higher Survivin levels than parental cells, consistent with the facts that these cells contain more Bcr-abl as a consequence of STI571 resistance (Figure 2C) and that Bcr-abl regulates Survivin transcription (Wang et al, 2005). In the parental K562 cells, ectopic Survivin protected cells from STI571-induced apoptosis, while Survivin disruption promoted apoptosis as expected (Figure 1A). In STI571-resistant cells (Figure 1B), ectopic Survivin still protected the cells from STI571-induced apoptosis although to a lesser degree than in parental cells, which is not unexpected, since these cells are drug resistant. However, Survivin disruption did not promote cell apoptosis, but rather protected cells to an equivalent degree as ectopic Survivin.

Figure 1.

Disruption of Survivin fails to promote STI571-induced apoptosis in STI571-resistant K562 cells. Parental (A) or STI571-resistant (B) K562 cells transfected with wild-type Survivin (S), antisense (AS) Survivin or control vector (V) were cultured with STI571 for 48 hours. Apoptosis was determined by quantitating hypodiploid DNA content. Representative western blots (insert) show Survivin levels after transfection. All data are expressed as Mean ±SEM from 3 experiments. *P<0.01.

Figure 2.

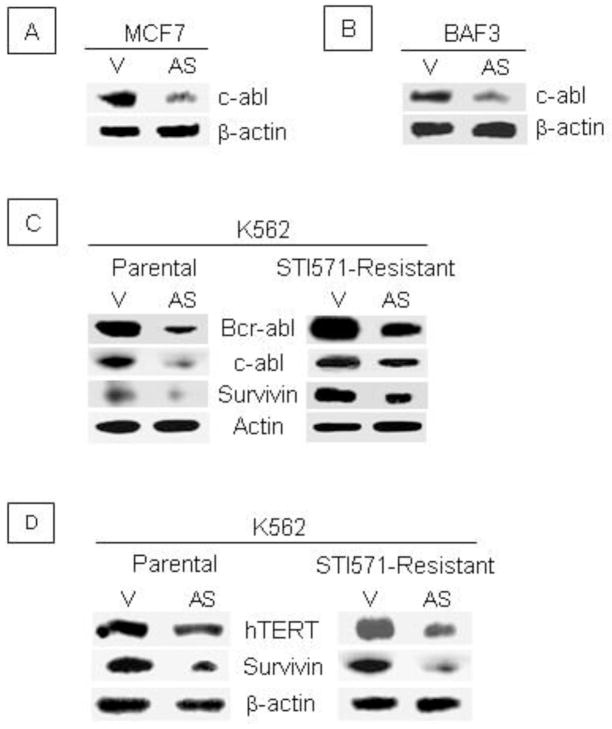

Survivin knockdown promotes Bcr-abl and c-abl degradation and reduces hTERT levels. Human MCF7 breast cancer cells (A) and murine hematopoietic BaF3 proB cells (B) were transiently transfected with antisense (AS) Survivin or control vector (V). After 24 hours, cell lysates were subjected to Western analysis using an anti-c-abl antibody. (C). Parental and STI571-resistant K562 cells stably transfected with antisense (AS) Survivin and control vector (V) were harvested and whole cell lysates analyzed by western analysis using anti-c-abl, anti-Bcr-abl and anti-Survivin antibodies. Data are representative from 3 experiments with similar results. (D). hTERT protein was determined by western analysis in parental and STI571-resistant cells transiently transfected with antisense Survivin or control vector. Data are representative of 2 experiments with similar results.

B. Survivin disruption decreases c-abl in MCF7 and BaF3 cells and Bcr-abl/c-abl in STI571- resistant K562 cells

Survivin blocks caspase activity while Survivin disruption increases caspase activity, favoring apoptosis. The finding of protection from apoptosis in STI571-resistant K562 cells led us to investigate caspase-3 activity. We previously showed that Survivin blocks caspase activity and caspase-dependent cleavage of Mdm2 in MCF7 and BaF3 cells (Wang et al, 2004) and several recent studies have described caspase-dependent cleavage of c-abl and Bcr-abl in K562 cells (Di Bacco and Cotter, 2002; Jacquel et al, 2003). Since Survivin inhibits caspase activity, and c-abl is a caspase substrate, we hypothesized that Survivin disruption could decrease c-abl and Bcr-abl. In both MCF7 cells transiently transfected with antisense Survivin and murine BaF3 cells stably transduced with antisense Survivin, Survivin disruption was associated with significantly lower levels of c-abl compared to vector control cells (Figures 2A and 2B). In parental and STI571-resistant K562 cells, Survivin disruption resulted in lower levels of both Bcr-abl and c-abl (Figure 2C). The demonstration of Bcr-abl/c-abl degradation suggests that alteration in caspase activity alone is not responsible for drug resistance.

C. High telomerase activity was found in STI571-resistant K562 cells after disruption of Survivin

Telomerase is a cellular RNA-dependent DNA polymerase that maintains the tandem arrays of telomeric TTAGGG repeats at eukaryotic chromosome ends (Greider and Blackburn, 1996; van Steensel et al, 1998). Telomerase activity is elevated in many cancers and immortalized cells (Engelhardt et al, 2000; Ohyashiki et al, 2002). It has been reported that c-abl directly associates with the catalytic protein subunit of human telomerase reverse transcriptase (hTERT) resulting in tyrosine phosphorylation and inhibition of telomerase activity (Kharbanda et al, 2000). Since Survivin disruption results in decreased Bcr-abl/c-abl levels, we reasoned that telomerase activity might increase as a consequence of reduced phosphorylation. In parental K562 cells, Survivin knockdown resulted in a marginal decrease in hTERT protein (Figure 2C; left panel); however, in drug-resistant K562 cells, hTERT protein was more dramatically reduced (Figure 2D; right panel). Interestingly, regardless of the hTERT protein level, telomerase activity was significantly increased in both parental and STI571-resistant cells transfected with antisense Survivin (Table 1). In STI571-resistant K562 cells, basal telomerase activity was significantly higher than in parental cells (for both vector control and AS Survivin cells), indicating that long-term inhibition of Bcr-abl by STI571 increases telomerase activity, which is consistent with published reports (Bakalova et al, 2003; Drummond et al, 2004). In addition, STI571-resistant K562 cells, in which Survivin was disrupted, had much longer telomere lengths compared to STI571-resistant K562 cells transfected with control vector (not shown).

Table 1.

Effect of Survivin knockdown on Telomerase activity in parental and STI571-resistant K562 cells

| Telomerase Activity (OD 490 nm) | ||

|---|---|---|

| V | AS | |

| Parental K562 | 1.51 ± 0.04 | 1.79 ± 0.05* |

| STI571 Resistant K562 | 1.89 ± 0.06† | 2.17 ± 0.09 *,† |

P <0.05 compared to vector control;

P <0.05 compared to parental K562 cells.

D. Survivin knockdown attenuates Hemin-induced apoptosis in K562 cells

Since Survivin knockdown leads to increased telomerase activity in both parental and STI571-resistant cells, we evaluated whether increased telomerase activity would result in reduced sensitivity to apoptosis induced by hemin, which induces apoptosis specifically by inhibiting telomerase activity (Benito et al, 1996; Yamada et al, 1998). In parental (Figure 3A) and resistant (Figure 3B) K562 cells, Survivin knockdown protected cells from hemin-induced apoptosis, although Survivin-mediated knockdown protected parental cells to a slightly greater degree than resistant cells. Inhibition of caspase-3 by the selective caspase inhibitor Z-VAD-FMK blocked apoptosis induced by STI571 in both control vector and antisense Survivin transfected K562 cells (Figure 4A). In contrast, caspase-3 inhibition was without effect on apoptosis induced by hemin either in the presence or absence of Survivin (Figure 4B), indicating that caspase-3 is not involved in hemin-induced apoptosis.

Figure 3.

Survivin knockdown attenuates hemin-induced apoptosis in K562 cells. (A). Parental K562 cells transfected with an antisense Survivin construct or vector alone were cultured with 30 μM hemin for 72 hours and hypodiploid DNA content quantitated by flow cytometry. Data are Mean ± SEM apoptosis from 6 experiments. *P<0.01. STI571-resistant K562 cells transfected with an antisense Survivin or vector were cultured with 30 μM hemin for 72 hours and hypodiploid DNA content and Annexin-V expression quantitated by flow cytometry. Data are Mean ± SEM from three experiments. *P<0.05.

Figure 4.

Caspase-3 inhibition attenuates hemin-induced apoptosis in K562 cells. (A). Parental K562 cells transfected with an antisense Survivin construct or vector were cultured in 0.5 μM STI571 with or without Z-DEVD-FMK for 48 hours. Apoptosis was quantitated based upon hypodiploid DNA content. Data are from 3 separate experiments. *P<0.01. (B). Transfected parental K562 cells were cultured in 30 μM hemin with or without Z-DEVD-FK for 72 hours and hypodiploid DNA content quantitated by flow cytometry. Data are from 2 experiments. *P<0.05. (C). Transfected parental K562 cells were cultured in 30 μM CDDP for 48 hours. Apoptosis was quantitated based upon hypodiploid DNA content. Data are from 3 separate experiments. *P<0.01.

While Bcr-abl and c-abl levels decrease in parental and drug-resistant cells after Survivin knockdown (Figure 2), likely resulting from increased caspase activity due to reduced Survivin protein, the reduction in c-abl is more dramatic. Since c-abl is required for CDDP-induced apoptosis (Gong et al, 1999) we questioned whether reduced apoptosis in resistant K562 cells upon Survivin disruption is a consequence of decreased c-abl levels or alternatively results from increased telomerase activity due to Bcr-abl/c-abl cleavage. Treatment with CDDP effectively induced apoptosis in control and K562 cells transfected with antisense Survivin (Figure 4C). Equivalent induction of apoptosis in both groups despite the fact that the antisense-transfected cells had significantly lower levels of c-abl indicates that c-abl cleavage does not play a significant role in apoptosis, and that Bcr-abl is the dominant mediator of apoptosis in these cells.

IV. Discussion

Bcr-abl kinase renders cells insensitive to apoptosis induced by diverse stimuli, including most cytotoxic drugs (McGahon et al, 1994; Bedi et al, 1995). Since we demonstrated previously that Survivin blocks caspase activity and caspase-dependent cleavage of Mdm2 (Wang et al, 2004) and Bcr-abl and c-abl are caspase substrates (Di Bacco and Cotter, 2002; Jacquel et al, 2003), we expected that Survivin knockdown might attenuate STI571-resistance by increasing caspase-mediated Bcr-abl cleavage. However, although Bcr-abl protein was decreased by Survivin knockdown, Survivin disruption did not enhance apoptosis; rather it blocked apoptosis induced by STI571. Data presented herein, suggests that this apoptosis enhancing effect is linked to the telomerase pathway.

Survivin blocks caspase 3 and 7 activity (O’Connor et al, 2000; Riedl et al, 2001) and promotes apoptosis. However, caspases mediate other biological processes besides apoptosis, such as cell differentiation (Gurbuxani et al, 2005) and can cleave a large number of cellular substrates, making it difficult to define a specific mechanism. Recently, it was reported that the p120 Ras GTPase-activating protein (RasGAP) can be cleaved into an N-terminal fragment by low levels of caspase, and that the cleavage products trigger antiapoptotic signals via activation of the Ras/PI-3 kinase/Akt pathway (Bartling et al, 2004). A similar mechanism might also occur in STI571-resistant K562 cells or Bcr-abl cleavage may trigger another signal pathway that increases telomerase activity. Alternatively, since c-abl associates with and directly phosphorylates hTERT and inhibits telomerase activity (Kharbanda et al, 2000), decreased Bcr-abl level resulting from Survivin disruption might interfere in this pathway and alter the apoptosis response.

Telomerase maintains the tandem repeats of TTAGGG at the telomere of eukaryotic chromosomes that protects them from end-to-end fusions (Greider and Blackburn, 1996; van Steensel et al, 1998). It is up-regulated in the vast majority of human tumors, and reconstitution of telomerase activity in cultured primary cells allows immortal growth (Bodnar et al, 1998; Kiyono et al, 1998; Jiang et al, 1999; Morales et al, 1999). The telomerase reverse transcriptase is a critical catalytic protein subunit within the telomerase complex (Feng et al, 1995; Weinrich et al, 1997). It has been reported recently that the c-abl tyrosine kinase directly associates with and phosphorylates hTERT and inhibits hTERT activity (Kharbanda et al, 2000). Therefore, c-abl protein and activity are potentially responsible for telomerase suppression. Moreover, chromosomal translocations that generate fusion proteins such as Tel-Abl and Tel-PDGFR, also correspond with low telomerase activity (Ohyashiki et al, 2002). Approximately 80% of CML patients show short telomere length and low telomerase activity in chronic phase (Ohyashiki et al, 1997), in contrasts to most leukemias, tumors and immortalized cell lines, where telomerase is usually overexpressed (Engelhardt et al, 2000; Ohyashiki et al, 2002). A link between the Bcr-abl with strong c-abl kinase activity and low telomerase activity during chronic phase CML has been suggested and accumulating evidences indicates that c-abl may suppress telomerase activity (Kharbanda et al, 2000; Ohyashiki et al, 2002). Enhanced telomerase activity is a prognostic indicator for shorter survival in CML patients. It seems likely that both Bcr-abl and telomerase abnormalities are responsible for disease progression, since Bcr-abl strongly activates c-abl kinase activity, thereby potentiating telomerase suppression. Consistent with this hypothesis, extension of telomeres in CML patients after long-term treatment with Gleevec in both chronic phase and blast crisis has been reported (Drummond et al, 2004). Long-term treatment with anti-Bcr-abl/c-abl antisense oligonucleotides also significantly elongates telomeres and enhances hTERT activity, accompanied by increased cell proliferation (Bakalova et al, 2003, 2004; Brummendorf et al, 2003). In this context, combination treatment with drugs targeting the Bcr-abl kinase and compounds influencing telomere length may be a promising strategy in treating CML. The demonstration that inhibition of human telomerase enhances the effect of Gleevec supports this assumption (Tauchi et al, 2002).

Survivin disruption elevated telomerase activity in both parental and drug-resistant K562 cells; however the consequence of apoptosis induction on these cells was opposite, raising the question of divergent versus convergent mechanisms. A possible explanation might be that in parental K562 cells, Bcr-abl cleavage by Survivin disruption produces only a moderate increase in telomerase activity that does not play a significant anti-apoptotic role. However, after STI571 selection, Bcr-abl inhibition leads to reduced hTERT phosphorylation and more significantly, enhanced telomerase activity. Furthermore, additional cleavage of Bcr-abl by Survivin disruption imparts a more predominant role for telomerase in blocking apoptosis. Indeed, the highest telomerase activity was observed in STI571-resistant cells in which Survivin was disrupted.

A recent report indicates that Survivin enhances telomerase activity in colon cancer through up regulation of hTERT transcription (Endoh et al, 2005). Consistent with this report, hTERT protein levels were decreased in K562 cells when Survivin protein levels are knocked down, however, telomerase activity did not parallel hTERT levels in K562 cells, pointing to potential differences between solid tumor cells and leukemia cells. This discrepancy might be explained by the fact that K562 cells like primary CML cells are distinct from most cancer and leukemia cells, in that they possess high levels of constitutively active Bcr-abl that phosphorylates hTERT and inhibits telomerase (Engelhardt et al, 2000; Ohyashiki et al, 2002, 1997). Blocking this inhibition either through chemical or biological means results in enhanced telomerase activity. Our results that Survivin disruption fails to promote apoptosis in resistant cells implies that drug resistance to STI571 affects additional signaling pathways in addition to increased gene amplification (Gorre and Sawyers, 2002) or mutations in the Bcr-abl catalytic domain (Shah et al, 2002) that have already been implicated in development of clinical resistance to STI571. However, although a Bcr-abl/telomerase axis pathway might play an important role it may only be specific to cells expressing high levels of c-abl kinase activity.

Acknowledgments

Supported by grants HL079654 and HL69669 (to LMP) from the National Institute of Health.

Abbreviations

- RasGAP

Ras GTPase-activating protein

- CML

Chronic Myeloid Leukemia

- CDDP

Cisplatin

- HI-FBS

heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum

- hTERT

human telomerase reverse transcriptase

- SDS-PAGE

SDS-polyacrylamide gels

- SDS

sodium dodecyl sulfate

References

- Ambrosini G, Adida C, Altieri DC. A novel anti-apoptosis gene, survivin, expressed in cancer and lymphoma. Nat Med. 1997;3:917–921. doi: 10.1038/nm0897-917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakalova R, Ohba H, Zhelev Z, Ishikawa M, Shinohara Y, Baba Y. Cross-talk between Bcr-Abl tyrosine kinase, protein kinase C and telomerase-a potential reason for resistance to Glivec in chronic myelogenous leukaemia. Biochem Pharmacol. 2003;66:1879–1884. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2003.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakalova R, Ohba H, Zhelev Z, Kubo T, Fujii M, Ishikawa M, Shinohara Y, Baba Y. Antisense inhibition of Bcr-Abl/c-Abl synthesis promotes telomerase activity and upregulates tankyrase in human leukemia cells. FEBS Lett. 2004;564:73–84. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(04)00318-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartling B, Yang JY, Michod D, Widmann C, Lewensohn R, Zhivotovsky B. RasGTPase-activating protein is a target of caspases in spontaneous apoptosis of lung carcinoma cells and in response to etoposide. Carcinogenesis. 2004;25:909–921. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgh075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedi A, Barber JP, Bedi GC, el-Deiry WS, Sidransky D, Vala MS, Akhtar AJ, Hilton J, Jones RJ. BCR-ABL-mediated inhibition of apoptosis with delay of G2/M transition after DNA damage: a mechanism of resistance to multiple anticancer agents. Blood. 1995;86:1148–1158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benito A, Silva M, Grillot D, Nuñez G, Fernández-Luna JL. Apoptosis induced by erythroid differentiation of human leukemia cell lines is inhibited by Bcl-XL. Blood. 1996;87:3837–3843. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodnar AG, Ouellette M, Frolkis M, Holt SE, Chiu CP, Morin GB, Harley CB, Shay JW, Lichtsteiner S, Wright WE. Extension of life-span by introduction of telomerase into normal human cells. Science. 1998;279:349–352. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5349.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brummendorf TH, Ersoz I, Hartmann U, Balabanov S, Wolke H, Paschka P, Lahaye T, Berner B, Bartolovic K, Kreil S, Berger U, Gschaidmeier H, Bokemeyer C, Hehlmann R, Dietz K, Lansdorp PM, Kanz L, Hochhaus A. Normalization of previously shortened telomere length under treatment with imatinib argues against a preexisting telomere length deficit in normal hematopoietic stem cells from patients with chronic myeloid leukemia. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003;996:26–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb03229.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Bacco AM, Cotter TG. p53 expression in K562 cells is associated with caspase-mediated cleavage of c-ABL and BCR-ABL protein kinases. Br J Haematol. 2002;117:588–597. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2002.03468.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Druker BJ, Talpaz M, Resta DJ, Peng B, Buchdunger E, Ford JM, Lydon NB, Kantarjian H, Capdeville R, Ohno-Jones S, Sawyers CL. Efficacy and safety of a specific inhibitor of the BCR-ABL tyrosine kinase in chronic myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1031–1037. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200104053441401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond M, Lennard A, Brûmmendorf T, Holyoake T. Telomere shortening correlates with prognostic score at diagnosis and proceeds rapidly during progression of chronic myeloid leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma. 2004;45:1775–1781. doi: 10.1080/10428190410001693542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endoh T, Tsuji N, Asanuma K, Yagihashi A, Watanabe N. Survivin enhances telomerase activity via up-regulation of specificity protein 1- and c-Myc-mediated human telomerase reverse transcriptase gene transcription. Exp Cell Res. 2005;305:300–311. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2004.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelhardt M, Mackenzie K, Drullinsky P, Silver RT, Moore MA. Telomerase activity and telomere length in acute and chronic leukemia, pre- and post-ex vivo culture. Cancer Res. 2000;60:610–617. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng J, Funk WD, Wang SS, Weinrich SL, Avilion AA, Chiu CP, Adams RR, Chang E, Allsopp RC, Yu J, et al. The RNA component of human telomerase. Science. 1995;269:1236–1241. doi: 10.1126/science.7544491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong JG, Costanzo A, Yang HQ, Melino G, Kaelin WG, Jr, Levrero M, Wang JY. The tyrosine kinase c-Abl regulates p73 in apoptotic response to cisplatin-induced DNA damage. Nature. 1999;399:806–809. doi: 10.1038/21690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorre ME, Sawyers CL. Molecular mechanisms of resistance to STI571 in chronic myeloid leukemia. Curr Opin Hematol. 2002;9:303–307. doi: 10.1097/00062752-200207000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greider CW, Blackburn EH. Telomeres, telomerase and cancer. Sci Am. 1996;274:92–97. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican0296-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurbuxani S, Xu Y, Keerthivasan G, Wickrema A, Crispino JD. Differential requirements for survivin in hematopoietic cell development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:11480–11485. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500303102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochhaus A, Kreil S, Corbin A, La Rosée P, Lahaye T, Berger U, Cross NC, Linkesch W, Druker BJ, Hehlmann R, Gambacorti- Passerini C, Corneo G, D’Incalci M. Roots of clinical resistance to STI-571 cancer therapy. Science. 2001;293:2163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacquel A, Herrant M, Legros L, Belhacene N, Luciano F, Pages G, Hofman P, Auberger P. Imatinib induces mitochondria-dependent apoptosis of the Bcr-Abl-positive K562 cell line and its differentiation toward the erythroid lineage. FASEB J. 2003;17:2160–2162. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang XR, Jimenez G, Chang E, Frolkis M, Kusler B, Sage M, Beeche M, Bodnar AG, Wahl GM, Tlsty TD, Chiu CP. Telomerase expression in human somatic cells does not induce changes associated with a transformed phenotype. Nat Genet. 1999;21:111–114. doi: 10.1038/5056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kharbanda S, Kumar V, Dhar S, Pandey P, Chen C, Majumder P, Yuan ZM, Whang Y, Strauss W, Pandita TK, Weaver D, Kufe D. Regulation of the hTERT telomerase catalytic subunit by the c-Abl tyrosine kinase. Curr Biol. 2000;10:568–575. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00483-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiyono T, Foster SA, Koop JI, McDougall JK, Galloway DA, Klingelhutz AJ. Both Rb/p16INK4a inactivation and telomerase activity are required to immortalize human epithelial cells. Nature. 1998;396:84–88. doi: 10.1038/23962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurzrock R, Gutterman JU, Talpaz M. The molecular genetics of Philadelphia chromosome-positive leukemias. N Engl J Med. 1988;319:990–998. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198810133191506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGahon A, Bissonnette R, Schmitt M, Cotter KM, Green DR, Cotter TG. BCR-ABL maintains resistance of chronic myelogenous leukemia cells to apoptotic cell death. Blood. 1994;83:1179–1187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morales CP, Holt SE, Ouellette M, Kaur KJ, Yan Y, Wilson KS, White MA, Wright WE, Shay JW. Absence of cancer-associated changes in human fibroblasts immortalized with telomerase. Nat Genet. 1999;21:115–118. doi: 10.1038/5063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor DS, Grossman D, Plescia J, Li F, Zhang H, Villa A, Tognin S, Marchisio PC, Altieri DC. Regulation of apoptosis at cell division by p34cdc2 phosphorylation of survivin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:13103–13107. doi: 10.1073/pnas.240390697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohyashiki JH, Sashida G, Tauchi T, Ohyashiki K. Telomeres and telomerase in hematologic neoplasia. Oncogene. 2002;21:680–687. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohyashiki K, Ohyashiki JH, Iwama H, Hayashi S, Shay JW, Toyama K. Telomerase activity and cytogenetic changes in chronic myeloid leukemia with disease progression. Leukemia. 1997;11:190–194. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2400560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennati M, Binda M, Colella G, Zoppe’ M, Folini M, Vignati S, Valentini A, Citti L, De Cesare M, Pratesi G, Giacca M, Daidone MG, Zaffaroni N. Ribozyme-mediated inhibition of survivin expression increases spontaneous and drug-induced apoptosis and decreases the tumorigenic potential of human prostate cancer cells. Oncogene. 2004;23:386–394. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riedl SJ, Renatus M, Schwarzenbacher R, Zhou Q, Sun C, Fesik SW, Liddington RC, Salvesen GS. Structural basis for the inhibition of caspase-3 by XIAP. Cell. 2001;104:791–800. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00274-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawyers CL. Chronic myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1330–1340. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199904293401706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah NP, Nicoll JM, Nagar B, Gorre ME, Paquette RL, Kuriyan J, Sawyers CL. Multiple BCR-ABL kinase domain mutations confer polyclonal resistance to the tyrosine kinase inhibitor imatinib (STI571) in chronic phase and blast crisis chronic myeloid leukemia. Cancer Cell. 2002;2:117–125. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00096-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin S, Sung BJ, Cho YS, Kim HJ, Ha NC, Hwang JI, Chung CW, Jung YK, Oh BH. An anti-apoptotic protein human survivin is a direct inhibitor of caspase-3 and -7. Biochemistry. 2001;40:1117–1123. doi: 10.1021/bi001603q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tauchi T, Nakajima A, Sashida G, Shimamoto T, Ohyashiki JH, Abe K, Yamamoto K, Ohyashiki K. Inhibition of human telomerase enhances the effect of the tyrosine kinase inhibitor, imatinib, in BCR-ABL-positive leukemia cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:3341–3347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Steensel B, Smogorzewska A, de Lange T. TRF2 protects human telomeres from end-to-end fusions. Cell. 1998;92:401–413. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80932-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Fukuda S, Pelus LM. Survivin regulates the p53 tumor suppressor gene family. Oncogene. 2004;23:8146–8153. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Sampath J, Fukuda S, Pelus LM. Disruption of the inhibitor of apoptosis protein survivin sensitizes Bcr-abl-positive cells to STI571-induced apoptosis. Cancer Res. 2005;65:8224–8232. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinrich SL, Pruzan R, Ma L, Ouellette M, Tesmer VM, Holt SE, Bodnar AG, Lichtsteiner S, Kim NW, Trager JB, Taylor RD, Carlos R, Andrews WH, Wright WE, Shay JW, Harley CB, Morin GB. Reconstitution of human telomerase with the template RNA component hTR and the catalytic protein subunit hTRT. Nat Genet. 1997;17:498–502. doi: 10.1038/ng1297-498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada O, Takanashi M, Ujihara M, Mizoguchi H. Down-regulation of telomerase activity is an early event of cellular differentiation without apparent telomeric DNA change. Leuk Res. 1998;22:711–717. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2126(98)00065-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]