Abstract

Difluoroboron dibenzoylmethane-polylactide, BF2dbmPLA, a biocompatible polymerluminophore conjugate was fabricated as nanoparticles. Spherical particles <100 nm in size were generated via nanoprecipitation. Intense blue fluorescence, two-photon absorption, and long-lived room temperature phosphorescence (RTP) are retained in aqueous suspension. The nanoparticles were internalized by cells and visualized by fluorescence microscopy. Luminescent boron biomaterials show potential for imaging and sensing.

Keywords: boron dye, fluorescence, phosphorescence, poly(lactic acid) (PLA), nanoparticles

Difluoroboron-based dyes, such as BODIPY1 and β-diketonate derivatives,2 exhibit large extinction coefficients, high emission quantum yields, large two-photon absorption cross-sections, and in some cases, sensitivity to the surrounding medium.3 These exceptional optical properties make them useful as imaging agents,4 photosensitizers,5 and sensors.6 Often dyes are combined with material substrates to modulate properties, enhance stability, and reduce toxicity. Dye leaching with associated toxicity and ambiguity in imaging and sensing schemes can be minimized with dye-polymer conjugates versus blends.7 For example, active agents such as Ru(II) complexes8,9 or metalloporphyrins10 are embedded in polymer matrices that act as protective shells and allow their use in biological contexts with increased stability and improved delivery11,12 by passive13,14 or active targeting.15 Many multifunctional imaging and sensing agents combine controlled material synthesis with nanofabrication.16,17 Nanoparticles based on luminescent dye conjugates and quantum dots18 are used to label intracellular structures and pathways in fundamental studies as well as for therapeutic and diagnostic purposes.19,20 Both fluorescence (singlet) and phosphorescence (triplet) emitters are widely used. Phosphorescence, in particular, is susceptible to oxygen quenching via triplet energy transfer, serving as the basis for oxygen sensing.21-23 Good oxygen permeability and fast response time are important factors. Photodynamic therapy, on the other hand, utilizes photosensitizers in combination with oxygen or other quenchers to generate reactive species for selective tissue treatment.24-26

Previously we reported that when boron difluoride dibenzoylmethane (BF2dbm) is combined with poly(lactic acid) (PLA), a biocompatible polymer,27 the intense blue fluorescence is retained and new properties emerge, namely temperature-sensitive delayed fluorescence and green oxygen-sensitive room-temperature phosphorescence (RTP).28 (We are unaware of similar multiemissive behavior for a single component BODIPY system at room or elevated temperatures.) The light emitting biomaterial, BF2dbmPLA, is readily processable as films, fibers, and particles. As a first step in exploring the potential of this class of materials for biological imaging, sensing and photodynamic therapies, we fabricate BF2dbmPLA as nanoparticles (<100 nm), verify that the unique emission properties persist in an aqueous environment, and demonstrate that cellular uptake of nanoparticles occurs without acute toxicity.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Difluoroboron dibenzoylmethane polylactide, BF2dbmPLA (Figure 1), was synthesized by ring opening polymerization of lactide using a hydroxyl-functionalized BF2dbm initiator and tin catalyst as previously described.28 Nanoparticles were produced by the solvent displacement method (i.e., nanoprecipitation)29,30 in which the polymer is dissolved in a solvent miscible with water (e.g., DMF) (oil phase), which is added to water, leading to the formation of droplets. Solvent diffusion results in a supersaturated oil phase, causing the formation of smaller droplets and a meta-stable emulsion.31 This method of fabrication was selected because nanoparticles of small size are typically obtained, particularly when DMF is used as the organic phase.25,32 In addition, the nanoprecipitation method avoids sonication that can damage the dye by shear forces and surfactants that can compete with the ligands, as we have observed previously for metal complexes.33 After fabrication, the morphology, size, chemical integrity, and optical properties of the nanoparticles were investigated. Preliminary cellular uptake studies were also performed.

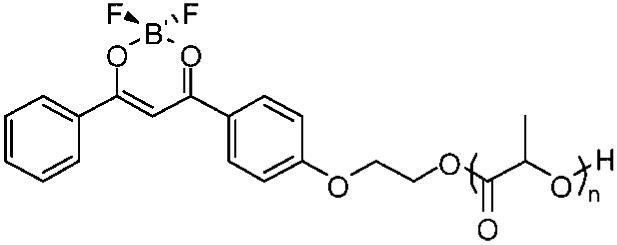

Figure 1.

Chemical structure of BF2dbmPLA.

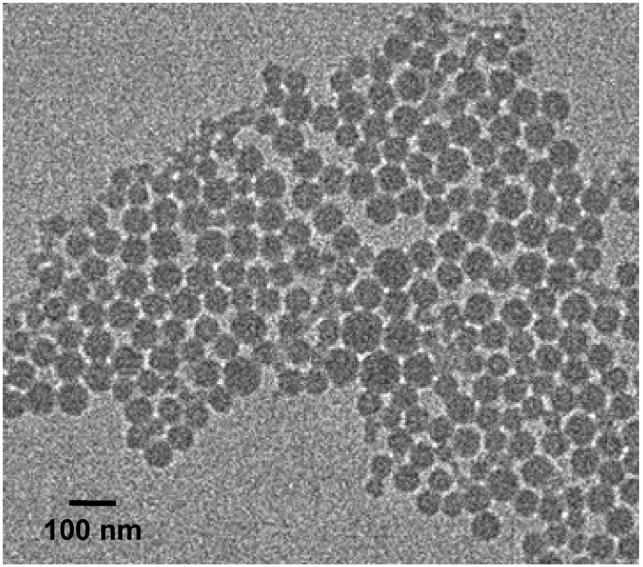

Particle morphology and size were assessed by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and dynamic light scattering (DLS). Spherical and fairly homogeneous particles were observed by TEM (Figure 2). Dynamic light scattering measurements indicated that suspended particles were 96 ± 8 nm in size with a polydispersity, Pd = 0.21 ± 0.03 (average of four preparations) and that the fabrication method showed good reproducibility. Because filtration can be important for biological studies, nanoparticle size was also assessed after passage through 0.2 μm nylon syringe filters. The size decreased (89 ± 8 nm) and the polydispersity increased slightly (Pd = 0.23 ± 0.07) under these conditions. A significant decrease in the particle size (68 nm, Pd = 0.23) was observed when an automatic syringe pump was used for the controlled addition of a larger volume of the polymer solution (20 vs 5 mL) to the water (200 vs 50 mL). These parameters are not usually cited in the literature as determinant of particle sizes, whereas the polymer concentration in the organic solvent and the volume ratio of the polymer solution to the water are and were kept constant in all the preparations.30,34

Figure 2.

TEM image of BF2dbmPLA nanoparticles.

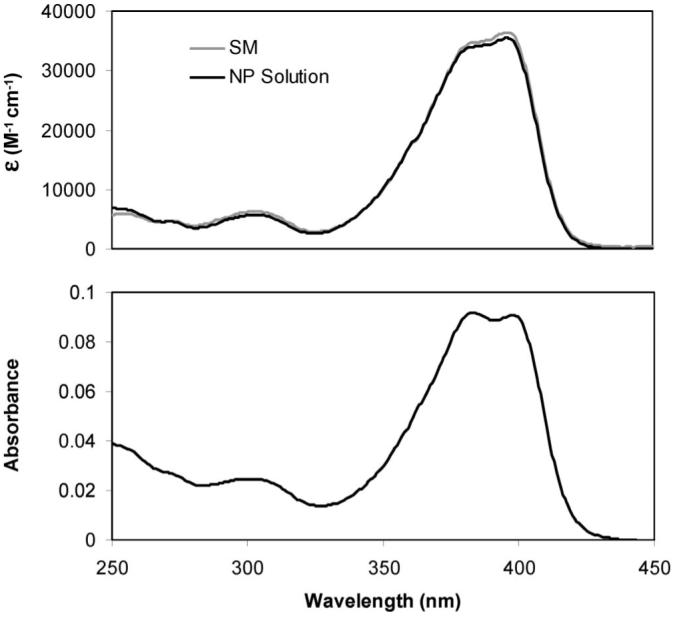

The chemical integrity of BF2dbmPLA after nanofabrication was assessed for a freeze-dried nanoparticle sample subsequently dissolved in appropriate solvents for gel permeation chromatography (GPC) and 1H NMR, UV-vis and fluorescence spectroscopies. GPC traces for the starting material (Mn = 10400, PDI = 1.18) and nanoparticle sample (Mn = 10400, PDI = 1.12) were similar. Polymer stability was further confirmed by 1H NMR spectroscopy, which also verified the efficient removal of DMF by dialysis. The UV-vis (Figure 3) and fluorescence (Figure 5) spectra for BF2dbmPLA in CH2Cl2 before and after fabrication are also similar (UV-vis: λmax = 396 nm, ε = 3.65 × 104 M-1 cm-1 (before), ε = 3.54 × 104 M-1 cm-1 (after); fluorescence: λem = 426 nm (before), λem = 426 nm (after)). Thus, the covalently attached boron fluorophore is not damaged during nanoparticle fabrication.

Figure 3.

UV-vis absorption spectra for the BF2dbmPLA starting material (SM) and freeze-dried nanoparticles (NP) dissolved in CH2Cl2 (∼2 μM; top) and for the nanoparticles in aqueous suspension (∼0.03 mg/mL; bottom).

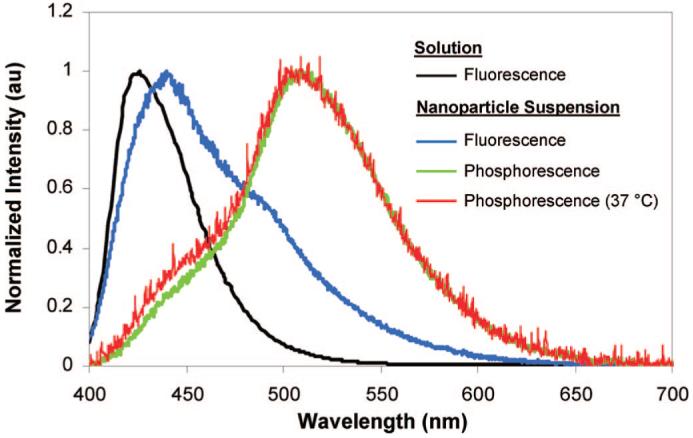

Figure 5.

Normalized emission spectra for BF2dbmPLA in CH2Cl2 solution and as an aqueous nanoparticle suspension (at 22 °C, unless otherwise specified).

The optical properties of the nanoparticles in aqueous suspension were also investigated. UV-vis spectra for the BF2dbmPLA particle suspensions are nearly identical to spectra for CH2Cl2 polymer solutions except that for the suspension the peak at 383 nm is more pronounced than the one at 398 nm (Figure 3). The strong blue fluorescence is also observed for nanoparticles in aqueous suspension (λem = 440 nm) (Figures 4 and 5). Compared to CH2Cl2 solutions, a small red shift is observed (Figure 5), which is similar to BF2dbmPLA solids (films: λem = 440 nm, powders: λem = 442 nm). The red-shifted spectrum may be indicative of dye-dye interaction in a single nanoparticle.35 Thus, the fluorescence properties of the colloidal suspensions and solids are in accord. Though suspensions can present challenges for optical measurements due to scattering, the fluorescence quantum yield for the particles was nonetheless measured and estimated as ϕF = 0.55. This value is lower than for BF2dbmPLA in CH2Cl2 (ϕF = 0.89)28 but still higher than commonly used dyes.36 The fluorescence lifetimes for the nanoparticles in aqueous suspension fit to a double exponential decay: τ1 = 3.3 ns (96%) and τ2 = 16.7 ns (4%). Double or multiexponential decay is common for BF2dbmPLA and other polymer-dye solids and may be attributable to fluorophore interaction or heterogeneous polymer microenvironments. Two-photon absorption, valuable for cell and tissue imaging with increased resolution and reduced damage37 and well documented for difluoroboron diketonate dyes,3 is conserved for the BF2dbmOH initiator. Preliminary results also indicate that BF2dbmPLA nanoparticles may be visualized using multiphoton microscopy (λex = 790 nm).

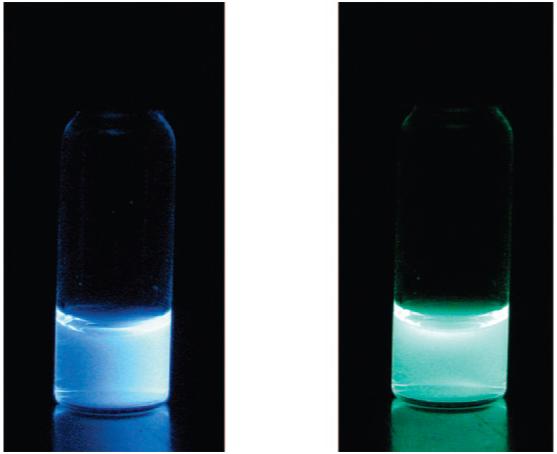

Figure 4.

Images showing fluorescence (left) and phosphorescence (right) of the nanoparticle aqueous suspension. (Fluorescence under air; phosphorescence imaged under a nitrogen atmosphere after the excitation source is turned off. λex = 365 nm.)

As previously demonstrated for films,28 BF2dbmPLA nanoparticle suspensions also exhibit long-lived room temperature phosphorescence (RTP) and consequently high sensitivity to oxygen quenching, making this system attractive for oxygen sensing applications. This may be contrasted with metal complex luminophores (such as Ru, Ln) that are sensitive to static and dynamic quenching in aqueous environments due to water coordination or O-H vibration.38,39 The delayed emission spectrum for BF2dbmPLA nanoparticles is similar to that of the film (RTP, λem = 509 nm; delayed fluorescence, λem ∼450 nm) (Figure 5). At body temperature (37 °C), the phosphorescence is conserved, an important prerequisite to the use of these nanomaterials in biological contexts. The thermally repopulated delayed fluorescence at ∼450 nm28 is increased slightly at elevated temperature, as expected. Preliminary studies suggest that nanoparticles in aqueous suspension (15 min Ar purge) and BF2dbmPLA films under vacuum exhibit similar phosphorescence lifetimes (∼200 ms). In both cases, data fit to triple exponential decay, and lifetimes decrease with increasing oxygen concentration.40 Compared to existing oxygen sensing systems (Ru(II)-tris(4,7-diphenyl-1,10-phenanthroline)2+, 5.3 μs; Pt(II)octaethylporphine ketone, 0.06-0.09 ms;36 Pd(II) porphyrin ketone, 0.48 ms41), BF2dbmPLA nanoparticles exhibit longer lifetimes and therefore enhanced sensitivity to oxygen quenching. Because PLA is permeable to oxygen, response times can be fast.42,43

PLA nanoparticles are known to degrade over 2 years time because of acid-catalyzed ester hydrolysis. The polymer molecular weight decreases slowly for 5 weeks, then more rapidly thereafter.44,45 To assess the shelf life of boron nanoparticles in aqueous suspension, their stability was monitored over time using GPC, 1H NMR, UV-vis, and fluorescence spectroscopies, and DLS. After 1, 5, and 11 weeks, aliquots were removed and freeze-dried. GPC analysis shows that the molecular weight decreases and the PDI broadens very slightly over time (after preparation, Mn = 10400, PDI = 1.12; 1 week, Mn = 9600, PDI = 1.20; 5 weeks, Mn = 8,700, PDI = 1.22; 11 weeks, Mn =7500, PDI = 1.37). After 11 weeks, the NMR spectrum shows a resonance at 6.8 ppm that is characteristic of the ArC(O)CH=C(OH)Ar’ proton in the free dbmPLA macroligand, suggesting hydrolysis of “BF2” from the dbm binding site for a fraction of the sample. However, the associated dbmPLA ArC(O)CH=C(OH)Ar’ enol proton peak at 16.98 ppm is not evident in BF2dbmPLA particle samples after 11 weeks; it was only observed in NMR spectra for samples analyzed after 5 months. A decrease in the UV-vis extinction coefficient, ε (M-1cm-1) at 396 nm over time is also consistent with degradation of the boron center (1 week: 3.40 × 104; 5 weeks: 2.78 × 104; 11 weeks: 1.94 × 104). Though the absolute intensity of the fluorescence emission necessarily changes with dye degradation, the emission maximum for boron nanoparticles does not vary over time when samples are analyzed in aqueous suspension or in CH2Cl2 solution after freeze-drying. Hydrolysis of BF2dbmPLA leads to a nonemissive dbmPLA degradation product, with little effect on nanoparticle emission spectra. Even after 8 months, the blue fluorescence is intense and room temperature phosphorescence is still evident for nanoparticle aqueous suspensions. As previously described,44 the nanoparticle size shows no significant change after 11 weeks (after preparation, 68 nm, Pd = 0.23; 11 weeks, 67 nm, Pd = 0.18).

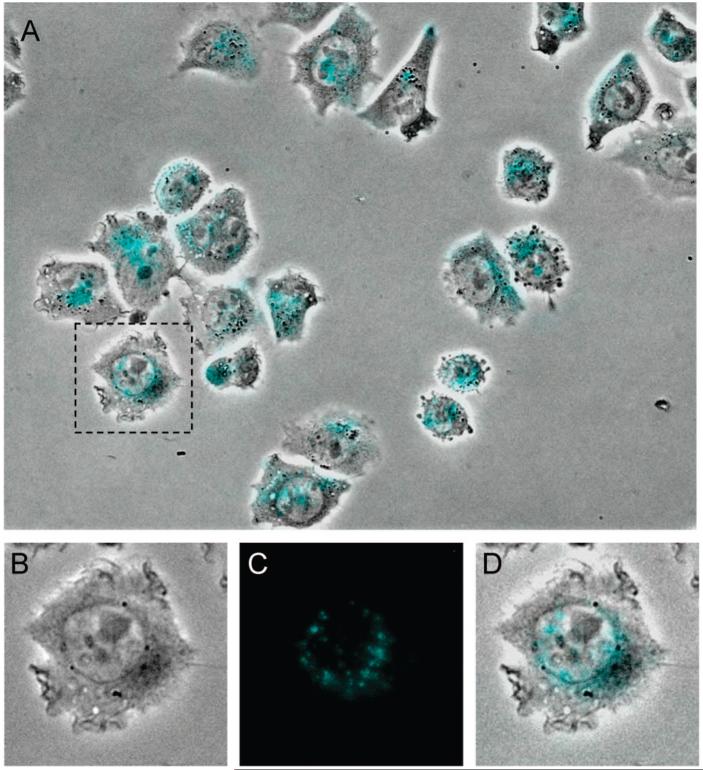

Given the unique optical properties and good stability exhibited in aqueous suspension over time, further studies exploring the potential of BF2dbmPLA nanoparticles and related derivatives for biological imaging, sensing, and photodynamic therapies are merited. Cellular uptake and evidence for the lack of acute toxicity are important to some of these applications. As a preliminary test, the cellular uptake of BF2dbmPLA nanoparticles was verified in vitro with Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells. The cells were treated with an aqueous suspension of filtered and unfiltered nanoparticles (unfiltered: size = 97 nm, Pd 0.19; filtered/0.2 μm: size = 78 nm, Pd 0.24) at different concentrations. For a concentration as low as 81 μg/mL, nanoparticle internalization was observed by fluorescence microscopy after 1 h, as is typically noted in the literature.25,46 Fluorescent nanoparticles were evident in the perinuclear region of the cells (Figure 6). After 3 days, fluorescence was still observed and a significant fraction of the cells were still viable. These preliminary observations indicate typical cell uptake behavior and the lack of acute toxicity for boron nanoparticles, verifying that further investigation and materials optimization is merited.

Figure 6.

Fluorescence and bright field microscopy image overlay (A) of CHO cells incubated for one hour with a filtered BF2dbmPLA nanoparticle suspension (405 μg/mL before filtration) and images of one cell showing the perinuclear localization of the fluorescent nanoparticles (bright field (B), fluorescence (C), and overlay (D) microscopy images; false color image).

CONCLUSION

In summary, multiemissive BF2dbmPLA was fabricated as nanoparticles. The preparation of nanoparticles with this single component material results in a well-defined, controllable product. The fabrication is easy and the covalent attachment of the active agent to the polymer matrix avoids more rapid dye hydrolysis and leaching. Optical properties for nanoparticles in aqueous suspension are similar to the solid polymer; intense fluorescence and long-lived room temperature phosphorescence conferring sensitivity to low oxygen levels were observed. Bright fluorescence and phosphorescence are retained for suspensions kept on the shelf for months even with normal degradation of the biodegradable polyester chains and gradual hydrolysis of the luminophores over time. Cell internalization and imaging without acute toxicity, as demonstrated here, combined with the unusually long-lived phosphorescence still present at 37 °C, raise the possibility of optical sensing in anaerobic environments or in hypoxia model systems. Future work will focus on the effect of polymer molecular weight on emission properties,35 oxygen sensitivity,40 and toxicity of these multiemissive particles, along with further optimization and testing of these materials for biological applications.

METHODS

Materials and Instrumentation

All chemicals were obtained from Aldrich. Syringe filters (13 mm, disposable filter device, nylon filter membrane) were obtained from Whatman. 1H NMR (300 MHz) spectra were recorded on a UnityInova 300/51 instrument and referenced to the signal for residual protio chloroform at 7.26 ppm. Molecular weights were determined by GPC (THF, 20 °C, 1.0 mL/min) versus polystyrene standards on a Hewlett-Packard instrument (series 1100 HPLC) equipped with Polymer Laboratories 5 μm mixed-C columns and connected to UV-vis and RI (Viscotek LR 40) detectors. Data were processed with the OmniSEC software (version 4.2, Viscotek Corp). A correction factor of 0.58 was applied to all data, as previously described.47 UV-vis spectra were recorded on a Hewlett-Packard 8453 diode-array spectrophotometer. Fluorescence emission spectra of optically dilute samples (abs < 0.1) were recorded on a FluoroLog fluorometer (Jobin Yvon-Horiba). Photographs in Figure 4 were taken in the dark using a Canon PowerShot SD600 Digital Elph camera with the automatic setting (no flash).

Nanoparticle Preparation

BF2dbmPLA (200 mg, Mn = 10400) dissolved in DMF (20 mL) was added dropwise to H2O (200 mL) using an automatic syringe pump. The water was stirred during the addition and the resulting homogeneous suspension was stirred for an additional 30 min. The suspension was then dialyzed in dialysis tubing (Spectra/Por, 12-14 kDa MWCO, Fisher Scientific) under slow stirring against distilled water following the procedure described in Ataman-Onal et al. for complete DMF removal.48 The suspension was analyzed as is or freeze-dried for further characterization.

Nanoparticle Size Determination

Nanoparticle sizes were determined by dynamic light scattering (90° angle) on a Photocor Complex (Photocor Instruments Inc., MD) equipped with a He-Ne laser (Coherent, CA, model 31-2082, 632.8 nm, 10 mW). Size and polydispersity analysis were performed using DynaLS software (Alango, Israel). The suspension was analyzed as such or diluted (0.5 mL) with Millipore water (9.5 mL). No significant difference of the size and polydispersity was observed in the diluted and undiluted samples although in some measurements larger size species appeared in the samples that were not diluted due to multiscattering.

Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

Drops of the diluted nanoparticle suspension (20 μL/10 mL deionized water) were deposited directly on carbon-coated electron microscope grids and were allowed to dry. Transmission electron microscopy was performed with a JEOL 200CX, tungsten filament, operated at 200 kV using low dose conditions required by the beam sensitivity of the material. Brightfield images were taken using a CCD camera (AMT).

Fluorescence Lifetimes

Time-resolved fluorescence measurements were performed by exciting the nanoparticle suspension under air with 160 fs pulses at 390 nm, the doubled output of a Coherent RegA Ti:Sapphire amplifier operating at 250 kHz. The resulting fluorescence was spectrally resolved with a Chromex 250is Imaging Spectrograph and temporally resolved with a Hamamatsu C4770 Streak Scope. Data were processed using Hamamatsu, Matlab, and Origin software. Emission data were collected twice for each sample to ensure reproducibility. Reported lifetimes represent an average of two runs, fitted for the entire emission curves.

Quantum Yields

The fluorescence quantum yield, ϕF, for the nanoparticle aqueous suspension under air was calculated versus anthracene in EtOH as a standard, as previously described49 using the following values: ϕF anthracene = 0.27,50 n D20 EtOH = 1.36, n D20 H2O = 1.333. The optically dilute nanoparticle suspension and the EtOH solution of the anthracene standard were prepared in 1 cm path length quartz cuvettes, and absorbances (A < 0.1) were recorded using a Hewlett-Packard 8453 UV/vis spectrometer. Steady state emission spectra were obtained from a custom-built Photon Technology Instruments fluorimeter installed with a Hamamatsu R928 photomultiplier tube and a 150 W Xe excitation lamp. PTI Felix 32 software was used to process the data (λex = 355 nm; emission integration range: 362-700 nm). Emission data were collected three times and averaged. The average spectra were used in the quantum yield calculation.

Multiphoton Microscopy

BF2dbmPLA nanoparticles may be visualized upon excitation with a femtosecond mode locked Ti:sapphire laser (λex = 790 nm) (Coherent, Inc.; pulse width, < 150 fs; repetition rate, 76 MHz; X-wave optics; pumping laser, Verdi, 532 nm, 5 W) using a Nikon PCM2000 laser scanning confocal coupled to a TE-200 epifluorescence microscope, using Simple PCI software.

Phosphorescence Spectra

The aqueous nanoparticle suspension (∼5 mL) in a vial was capped with a rubber septum and purged with N2 for ∼15 min. Emission spectra were recorded with an OceanOptics USB2000 fiber optic spectrometer using a hand-held UV lamp (λex = 365 nm; long wavelength setting). For the delayed emission at 37 °C, the purged sample vial was placed in a temperature controlled Pyrex water bath, the temperature was allowed to equilibrate for ∼10 min, and then the spectrum was recorded.

Phosphorescence Lifetimes

Measurements were performed using instrumentation and methods previously described for BF2dbmPLA films28 with the following exceptions. An aqueous nanoparticle suspension (∼2 mL) was placed in a quartz cuvette sealed with a screw cap containing a septum (Hellma). The suspension was sparged with argon containing variable amounts of oxygen (∼0 to 1%) for 15 min, before lifetime data were recorded.

Cell Culture

Chinese hamster ovary cells (CHO-K1; P10) were seeded with a complete growth media Dulbecco’s Modified Essential Medium (DMEM) (1X) liquid (low glucose) (Gibco) containing 1,000 mg/L d-glucose, l-glutamine, pyridoxine HCl, and 110 mg/L sodium pyruvate and supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 1 mM nonessential amino acids, and 1 mM penicillin-streptomycin. The cells were trypsinized and plated on fibronectin-treated (2 μg) glass-bottom 35 mm tissue culture dishes and allowed to spread for 2 h. The nanoparticle suspension (1, 10, 100, and 500 μL) was diluted in complete media (1 mL) and plated on the cells for 1 h incubation at 37 °C and 8.5% CO2. After incubation, the cells were rinsed twice with 1X PBS and replaced with CCM1 media for imaging. Nanoparticle cellular uptake was observed with a Nikon IX 300 brightfield and fluorescence microscope. The images were obtained with a Retiga camera with the Metamorph Imaging Software (DAPI filter/cube (ex 330-380/em 435-485); 1000 ms exposure).

Acknowledgment

We thank the following persons for experimental assistance, use of facilities, and helpful discussions: (UVA) Prof. J. N. Demas (spectra, phosphorescence lifetime), and Prof. D. L. Green and N. Dutta (DLS); (MIT) D. Alcazar (TEM), R. C. Somers (quantum yield), Dr. S. E. Kooi (fluorescence lifetime), Prof. E. L. Thomas, and Prof. D. G. Nocera. This work was supported by the National Science Foundation (Grants BES-0402212, CHE-0350121) (C.L.F.), the National Institutes of Health (Cell Migration Consortium GM64346, GM23244) (A.F.H.), and the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study at Harvard University (C.L.F.).

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.BODIPY = 4,4-difluoro-4-bora-3a,4a-diaza-s-indacene.Loudet A, Burgess K. BODIPY Dyes and Their Derivatives: Syntheses and Spectroscopic Properties. Chem. Rev. 2007;107:4891–4832. doi: 10.1021/cr078381n.

- 2.Chow YL, Johansson CI, Zhang Y-H, Gautron R, Yang L, Rassat A, Yang S-Z. Spectroscopic and Electrochemical Properties of 1,3-Diketonatoboron Derivatives. J. Phys. Org. Chem. 1996;9:7–16. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cogné-Laage E, Allemand J-F, Ruel O, Baudin J-B, Croquette V, Blanchard-Desce M, Jullien L. Diaroyl(methanato)boron Difluoride Compounds as Medium-Sensitive Two-Photon Fluorescent Probes. Chem. Eur. J. 2004;10:1445–1455. doi: 10.1002/chem.200305321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haugland RP. In: The Handbook-A Guide to Fluorescent Probes and Labeling Technologies. 10th ed. Spence MTZ, editor. Molecular Probes; Eugene, OR: 2005. Chapter 1, Section 1.4. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yogo T, Urano Y, Ishisuka Y, Maniwa F, Nagano T. Highly Efficient and Photostable Photosensitizer Based on BODIPY Chromophore. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:12162–12163. doi: 10.1021/ja0528533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Méallet-Renault R, Hérault A, Vachon J-J, Pansu RB, Amigoni-Gerbier S, Larpent C. Fluorescent Nanoparticles as Selective Cu(II) Sensors. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2006;5:300–310. doi: 10.1039/b513215k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sun H, Scharff-Poulsen AM, Gu H, Almdal K. Synthesis and Characterization of Ratiometric, pH Sensing Nanoparticles with Covalently Attached Fluorescent Dyes. Chem. Mater. 2006;18:3381–3384. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carraway ER, Demas JN, DeGraff BA, Bacon JR. Photophysics and Photochemistry of Oxygen Sensors Based on Luminescent Transition-Metal Complexes. Anal. Chem. 1991;63:337–342. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guice KB, Caldorera ME, McShane MJ. Nanoscale Internally Referenced Oxygen Sensors Produced From Self-Assembled Nanofilms on Fluorescent Nanoparticles. J. Biomed. Opt. 2005;10:64031-1–64031-10. doi: 10.1117/1.2147419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Briñas RP, Troxler T, Hochstrasser RM, Vinogradov SA. Phosphorescent Oxygen Sensor with Dendritic Protection and Two-Photon Absorbing Antenna. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:11851–11862. doi: 10.1021/ja052947c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koo YE, Cao Y, Kopelman R, Koo SM, Brasuel M, Philbert MA. Real-Time Measurements of Dissolved Oxygen Inside Live Cells by Organically Modified Silicate Fluorescent Nanosensors. Anal. Chem. 2004;76:2498–2505. doi: 10.1021/ac035493f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhu H, McShane MJ. Loading of Hydrophobic Materials into Polymer Particles: Implications for Fluorescent Nanosensors and Drug Delivery. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:13448–13449. doi: 10.1021/ja052188y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maeda H, Wu J, Sawa T, Matsumura Y, Hori K. Tumor Vascular Permeability and the EPR Effect in Macromolecular Therapeutics: A Review. J. Controlled Release. 2000;65:271–284. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(99)00248-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brigger I, Dubernet C, Couvreur P. Nanoparticles in Cancer Therapy and Diagnosis. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 2002;54:631–651. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(02)00044-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.LaVan DA, McGuire T, Langer R. Small-Scale Systems for in Vivo Drug Delivery. Nat. Biotechnol. 2003;21:1184–1191. doi: 10.1038/nbt876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Whitesides GM. Nanoscience, Nanotechnology, and Chemistry. Small. 2005;1:172–179. doi: 10.1002/smll.200400130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Farokhzad OC, Langer R. Nanomedicine: Developing Smarter Therapeutic and Diagnostic Modalities. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 2006;58:1456–1459. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2006.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Medintz IL, Uyeda HT, Goldman ER, Mattoussi H. Quantum Dot Bioconjugates for Imaging, Labelling and Sensing. Nat. Mater. 2005;4:435–446. doi: 10.1038/nmat1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Torchilin VP. Fluorescence Microscopy to Follow the Targeting of Liposomes and Micelles to Cells and Their Intracellular Fate. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 2005;57:95–109. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2004.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Licha K, Olbrich C. Optical Imaging in Drug Discovery and Diagnostic Applications. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 2005;57:1087–1108. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2005.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vanderkooi JM, Maniara G, Green TJ, Wilson DF. An Optical Method for Measurement of Dioxygen Concentration Based Upon Quenching of Phosphorescence. J. Biol. Chem. 1987;262:5476–5482. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sánchez-Barragán I, Costa-Fernández JM, Valledor M, Campo JC, Sanz-Medel A. Room-Temperature Phosphorescence (RTP) for Optical Sensing. Trend. Anal. Chem. 2006;25:958–967. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cochran DM, Fukumura D, Ancukiewicz M, Carmeliet P, Jain RK. Evolution of Oxygen and Glucose Concentration Profiles in a Tissue-Mimetic Culture System of Embryonic Stem Cells. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2006;34:1247–1258. doi: 10.1007/s10439-006-9134-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gao D, Agayan RR, Xu H, Philbert MA, Kopelman R. Nanoparticles for Two-Photon Photodynamic Therapy in Living Cells. Nano Lett. 2006;6:2383–2386. doi: 10.1021/nl0617179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McCarthy JR, Perez JM, Bruckner C. Weissleder, R. Polymeric Nanoparticle Preparation that Eradicates Tumors. Nano Lett. 2005;5:2552–2556. doi: 10.1021/nl0519229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Konan YN, Chevallier J, Gurny R, Allémann E. Encapsulation of p-THPP into Nanoparticles: Cellular Uptake, Subcellular Localization and Effect of Serum on Photodynamic Activity. Photochem. Photobiol. 2003;77:638–644. doi: 10.1562/0031-8655(2003)077<0638:eopinc>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dechy-Cabaret O, Martin-Vaca B, Bourissou D. Controlled Ring-Opening Polymerization of Lactide and Glycolide. Chem. Rev. 2004;104:6147–6176. doi: 10.1021/cr040002s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang G, Chen J, Payne SJ, Kooi SE, Demas JN, Fraser CL. Difluoroboron Dibenzoylmethane Polylactide Exhibiting Room Temperature Phosphorescence. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:8942–8943. doi: 10.1021/ja0720255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fessi H, Puisieux F, Devissaguet J. Ph., Ammoury N, Benita S. Nanocapsule Formation by Interfacial Polymer Deposition Following Solvent Displacement. Int. J. Pharm. 1989;55:R1–R4. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Avgoustakis K. Pegylated Poly(lactide) and Poly(lactide-co-glycolide) Nanoparticles: Preparation, Properties and Possible Applications in Drug Delivery. Curr. Drug Delivery. 2004;1:321–333. doi: 10.2174/1567201043334605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ganachaud F, Katz JL. Nanoparticles and Nanopcapsules Created Using the Ouzo Effect: Spontaneous Emulsification as an Alternative to Ultrasonic and High-Shear Devices. Chem. Phys. Chem. 2005;6:209–216. doi: 10.1002/cphc.200400527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cheng J, Teply BA, Sherifi I, Sung J, Luther G, Gu FX, Levy-Nisenbaum E, Radovic-Moreno AF, Langer R, Farokhzad OC. Formulation of Functionalized PLGA-PEG Nanoparticles for in Vivo Targeted Drug Delivery. Biomaterials. 2007;28:869–876. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.09.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pfister A, Chen J, Chen YJ, Fraser CL. Iron Tris(dibenzoylmethane-polylactide) Nanoparticles. Polym. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2007;96:923. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bilati U, Allémann E, Doelker E. Development of a Nanoprecipitation Method Intended for the Entrapment of Hydrophilic Drugs into Nanoparticles. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2005;24:67–75. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2004.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang G, Kooi SE, Demas JN, Fraser CL. Emission Color Tuning with Polymer Molecular Weight for Difluoroboron Dibenzoylmethane-Polylactide. Adv. Mater. 2008 in press. [Google Scholar]

- 36.As examples, for Ru(II)-tris(4,7-diphenyl-1,10-phenanthroline) 2+, fF = 0.3; for Pt(II)octaethylporphine ketone, fF = 0.1-0.5; see:Cao Y, Koo Y-EL, Kopelman R. Poly(decyl methacrylate)-Based Fluorescent PEBBLE Swarm Nanosensors for Measuring Dissolved Oxygen in Biosamples. Analyst. 2004;129:745–750. doi: 10.1039/b403086a.

- 37.So PT, Dong CY, Masters BR, Berland KM. Two-Photon Excitation Fluorescence Microscopy. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2000;2:399–429. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.2.1.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Delgadillo A, Arias M, Leiva AM, Loeb B, Meyer GJ. Interfacial Charge-Transfer Switch: Ruthenium-dppz Compounds Anchored to Nanocrystalline TiO2. Inorg. Chem. 2006;45:5721–5723. doi: 10.1021/ic060427s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Huignard A, Buissette V, Franville A-C, Gacoin T, Boilot J-P. Emission Processes in YVO4:Eu Nanoparticles. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2003;107:6754–6759. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Technical challenges associated with simultaneous control of oxygen concentration and temperature for boron nanoparticles preclude detailed quantitative calibration of oxygen sensitivity with the present setup. Alternative instrumentation for sensitive oxygen calibration measurements requires modification for long phosphorescence lifetimes. (For example, see:Rozhkov V, Wilson DF, Vinogradov S. Phosphorescent Pd Porphyrin-Dendrimers: Tuning Core Accessibility by Varying the Hydrophobicity of the Dendrimer Matrix. Macromolecules. 2002;35:1991–1993.Supporting Information.) Oxygen calibration of BF2dbmPLA nanoparticles requiring the development of new instrumentation will serve as the subject of future reports.

- 41.Papkovsky DB, Ponomarev GV, Trettnak W, O'Leary P. Phosphorescent Complexes of Porphyrin Ketones: Optical Properties and Application to Oxygen Sensing. Anal. Chem. 1995;67:4112–4117. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Auras R, Harte B, Selke S. Effect of Water on the Oxygen Barrier Properties of Poly(ethylene terephthalate) and Polylactide Films. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2004;92:1790–1803. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bao L, Dorgan JR, Knauss D, Hait S, Oliveira NS, Maruccho IM. Gas Permeation Properties of Poly(lactic acid) Revisited. J. Membr. Sci. 2006;285:166–172. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zweers MLT, Engbers GHM, Grijpma DW, Feijen J. In Vitro Degradation of Nanoparticles Prepared from Polymers Based on d,l-Lactide, Glycolide and Poly(ethylene oxide) J. Controlled Release. 2004;100:347–356. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2004.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Alexis F. Factors Affecting the Degradation and Drug-Release Mechanism of Poly(lactic acid) and Poly[(lactic acid)-co-(glycolic acid)] Polym. Int. 2005;54:36–46. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Panyama J, Sahoo SK, Prabha S, Bargar T, Labhasetwar V. Fluorescence and Electron Microscopy Probes for Cellular and Tissue Uptake of Poly(d,l-lactide-co-glycolide) Nanoparticles. Int. J. Pharm. 2003;262:1–11. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5173(03)00295-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gorczynski JL, Chen J, Fraser CL. Iron Tris(dibenzoylmethane)-Centered Polylactide Stars: Multiple Roles for the Metal Complex in Lactide Ring-Opening Polymerization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:14956–14957. doi: 10.1021/ja0530927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ataman-Onal Y, Munier S, Ganée A, Terrat C, Durand P-Y, Battail N, Martinon F, Le Grand R, Charles M-H, Delair T, Verrier B. Surfactant-Free Anionic PLA Nanoparticles Coated with HIV-1 p24 Protein Induced Enhanced Cellular and Humoral Immune Responses in Various Animal Models. J. Controlled Release. 2006;112:175–185. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2006.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Demas JN, Crosby GA. Measurement of Photoluminescence Quantum Yields. Review. J. Phys. Chem. 1971;75:991–1024. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Melhuish WH. Quantum Effeciencies of Fluorescence of Organic Substances: Effect of Solvent and Concentration of the Fluorescent Solute. J. Phys. Chem. 1961;65:229–235. [Google Scholar]