Abstract

Simian virus 40 (SV40) provides a model system for the study of eukaryotic DNA replication, in which the viral protein, large T antigen (Tag), marshals host proteins to replicate the viral minichromosome. SV40 replication requires interaction of Tag with the host single-stranded DNA-binding protein, replication protein A (RPA). The C-terminal domain of the hRPA32 subunit (RPA32C) facilitates initiation of replication, but whether it interacts with Tag is not known. Affinity chromatography and NMR revealed physical interaction between hRPA32C and the Tag origin DNA–binding domain, and a structural model of the complex was determined. Point mutations were then designed to reverse charges in the binding sites, resulting in substantially reduced binding affinity. Corresponding mutations introduced into intact hRPA impaired initiation of replication and primosome activity, implying that this interaction has a critical role in assembly and progression of the SV40 replisome.

The fundamental biochemical steps in eukaryotic DNA replication were first elucidated in studies of a simple but effective model system, the cell-free replication of the SV40 genome. A single viral protein, Tag, orchestrates the entire replication process in primate cell extracts. Tag directs the initiation of viral replication by specifically binding to the SV40 origin of DNA replication, assembling into a double hexameric helicase that unwinds the duplex DNA bidirectionally, and recruiting cellular initiation proteins1–4. The progression of SV40 replication requires single-stranded DNA (ssDNA)-binding protein RPA, which binds to the free ssDNA generated by the Tag helicase and, together with Tag, enables primer synthesis and extension by DNA polymerase α-primase (pol-prim). The host replication machinery carries out all subsequent steps.

The molecular mechanism that coordinates the activities of Tag and human RPA (hRPA) in initiation of SV40 replication is not known. It is increasingly apparent that DNA processing events involve modular proteins that contain multiple structural and functional domains and have multiple points of contact5. Tag and hRPA are both modular proteins2,6–11 and the activity of hRPA in initiation of viral DNA replication correlates well with its ability to interact physically with Tag; budding yeast RPA and bacterial single-stranded DNA-binding proteins that support origin unwinding but not initiation bind poorly to Tag12–14. These results and other genetic and biochemical data strongly suggest that direct physical interactions between Tag and hRPA are crucial for initiation of SV40 replication.

To elucidate the molecular mechanism that coordinates Tag-hRPA activities in initiation of replication, the interaction site(s) between the two proteins must be mapped. The Tag origin DNA–binding domain (Tag-OBD) has been identified as a hRPA-interacting site15, and the 70-kDa subunit of hRPA has been shown to be involved in Tag interactions16. RPA32C, a winged helix-loop-helix, is a known protein interaction module17, but its ability to bind to Tag and its role in SV40 replication are controversial16,18. Here, we demonstrate that hRPA32C interacts with Tag and plays a critical role in stimulating the initiation of SV40 replication. These findings show that the interaction between Tag and hRPA involves multiple contact points, a critical feature that we incorporate into a refined mechanistic model for primer synthesis during SV40 replication.

RESULTS

An hRPA32C antibody inhibits initiation of SV40 replication

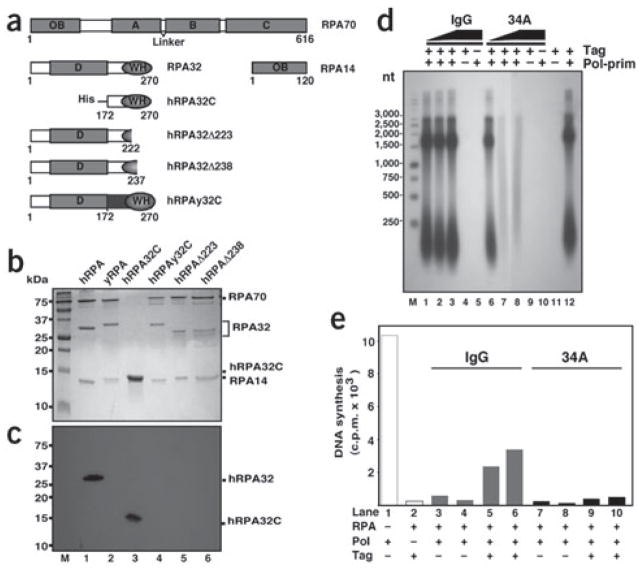

Our studies were initiated based on the observation that an antibody against hRPA32 (Ab34A) specifically inhibited SV40 DNA replication in crude extracts in vitro19. Ab34A has little effect on ssDNA-binding activity of hRPA, its ability to support origin DNA unwinding or to stimulate DNA polymerase δ activity, but it inhibits hRPA stimulation of DNA polymerase α activity19. To map the epitope recognized by Ab34A, hRPA and yeast RPA (yRPA) as well as hRPA-carrying mutations in RPA32, were tested for recognition by Ab34A in western blots (Fig. 1). Ab34A detected hRPA32 but not yRPA32 (Fig. 1c, lanes 1 and 2). hRPA32C alone (RPA(172–270)) was sufficient to bind Ab34A (lane 3) but a hRPA chimera with RPA32C substituted by the yeast domain (hRPAy32C) did not (lane 4). Moreover, deletions of 33 or 48 residues from hRPA32C, which are predicted to destroy the globular structure of the domain, also prevented binding of Ab34A (lanes 5 and 6). These data imply that the antibody recognizes an epitope in hRPA32C.

Figure 1.

Monoclonal antibody 34A recognizes hRPA32C and inhibits SV40 replication. (a) hRPA subunits and mutant proteins used in this study. Residue numbers are listed below each construct. OB, oligonucleotide-oligosaccharide binding folds, including the ssDNA-binding domains A– D; WH, winged helix-loop-helix domain. (b) Purified recombinant hRPA proteins were analyzed by 15% SDS-PAGE and Coomassie blue staining. M, protein markers of indicated mass. (c) Western blot assay of the proteins shown in b, probed with 34A monoclonal antibody and visualized by chemiluminescence. (d) Ab34A IgG or nonimmune mouse IgG was titrated into SV40 monopolymerase assays reconstituted with purified recombinant proteins. Products were resolved by alkaline agarose gel electrophoresis and visualized by autoradiography. Lanes 1–3 and 6–8, reactions containing 100, 300 or 500 ng of the indicated antibody. Control reactions carried out in the presence of 500 ng of antibody and in the absence of T antigen or pol-prim are indicated (−). M, DNA size marker of the indicated length in nucleotides (nt). (e) Primer synthesis and extension on M13mp18 ssDNA (25 ng) preincubated with 500 ng (lanes 3, 5, 7 and 9) or 750 ng (lanes 2, 4, 6, 8 and 10) of hRPA was tested in the presence of 250 ng pol-prim and 500 ng of either nonimmune IgG (lanes 3–6) or Ab34A (lanes 7–10). Control reactions with pol-prim alone (lane 1) and in the absence of pol-prim (lane 2) are indicated (−).

To confirm that Ab34A inhibits initiation of SV40 DNA replication, monopolymerase reaction assays20 were done using purified proteins. In this assay, synthesis of radiolabeled DNA depends on T-antigen assembly on the SV40 origin DNA, unwinding of the duplex, and synthesis of RNA primers that can then be extended. Radiolabeled products were analyzed by denaturing gel electrophoresis followed by autoradiography (Fig. 1d). Robust DNA replication occurred in a positive control reaction carried out in the absence of antibody (Fig. 1d, lane 12). Negative control reactions yielded no detectable products (Fig. 1d, lanes 4, 5 and 9–11). Addition of Ab34A inhibited initiation in a dose-dependent manner, but the presence of a nonimmune control antibody had no effect (Fig. 1d, compare lanes 1–3 with 6–8).

Previous studies with Ab34A indicated that the antibody did not interfere with unwinding of the origin DNA19, suggesting that it might inhibit the subsequent primer synthesis and elongation steps in initiation. To determine whether hRPA32C is required for these processes, ssDNA saturated with hRPA was used as template for synthesis of unlabeled primers and extension into radiolabeled DNA products by pol-prim. Priming is inhibited on ssDNA saturated with hRPA, but in the presence of Tag, pol-prim assembles into a functional primosome capable of primer synthesis on the hRPA-ssDNA template13,14,20. As expected, robust primer synthesis and elongation was observed on naked ssDNA template (Fig. 1e, lane 1), and when the ssDNA was saturated with hRPA, little synthesis was detected (lanes 3, 4, 7 and 8). Addition of Tag stimulated priming and elongation in the presence of nonimmune control antibody (compare lanes 5 and 6 with 3 and 4). However, in the presence of Ab34A, Tag did not stimulate priming and elongation (compare lanes 9 and 10 with 5 and 6). Hence, Ab34A interferes with the ability of Tag to mediate priming and elongation by pol-prim. Together, these data suggest a possible physical interaction between Tag and hRPA32C that facilitates priming and extension.

RPA32C interacts specifically with Tag-OBD

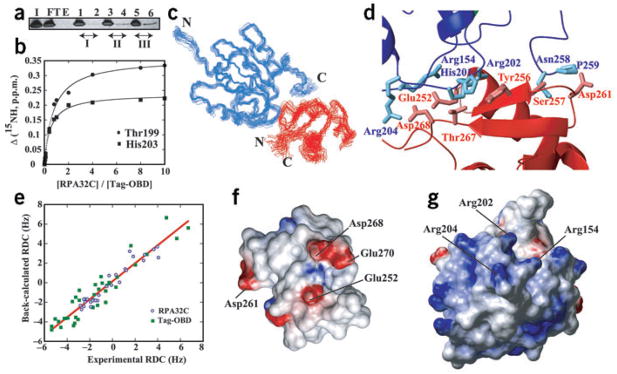

We tested for direct interaction between Tag and hRPA32C using affinity chromatography experiments. Initial experiments suggested an interaction with Tag-OBD. To confirm this observation, Tag-OBD was passed over columns containing increasing amounts of hRPA32C attached to the stationary phase (Fig. 2a). After vigorous washing, the eluted fractions were collected and separated on SDS-PAGE. Eluates from the hRPA32C column contained increasing amounts of Tag-OBD in proportion to the amount of hRPA32C attached to the beads (Fig. 2a, lanes 2, 4 and 6).

Figure 2.

The interaction of hRPA32C with Tag-OBD. (a) Tag-OBD affinity chromatography. Lanes: I, column input; FT and E, flow-through and elution fractions from the control column; 1 and 2, flow-through and elution fractions from column I; 3 and 4, flow-through and elution fractions from column II; 5 and 6, flow-through and elution fractions from column III, respectively. The bands were quantified using Image Quant 5.0 (Molecular Dynamics). The relative amount of Tag-OBD in the elution fractions for columns I, II and III (0.25:1.00:2.75) is similar to the relative amounts of hRPA32C (0.3:0.9:3.0) used in generating the corresponding columns. All flow-through bands were saturated. (b) NMR 15N chemical shift titration curves for the binding of hRPA32C to 15N-labeled Tag-OBD. The changes in amide nitrogen chemical shifts of Thr199 and His203 in Tag are plotted against the ratio of Tag-OBD to hRPA32C. The line through each curve represents a best fit to the standard single-site binding equation. (c) Ensemble of 20 lowest-energy conformers of the complex of Tag (blue) and hRPA32C (red). (d) Side chains in the binding interface of the representative Tag-OBD–RPA32C structure. Tag-OBD is blue and hRPA32C is red. The side chains are not as well defined as the backbone, so conclusions should not be drawn regarding specific intermolecular interactions apparent in this figure showing only a single conformer. (e) Correlation between the experimentally measured 1DNH residual dipolar couplings (RDC) versus the values back-calculated from the representative structure. (f,g) Electrostatic surfaces of the two molecules in the Tag-OBD–RPA32C complex. Red and blue, negative and positive charge, respectively. Key residues in the binding interface are labeled.

To further characterize the interaction, a series of 15N-1H HSQC NMR spectra were acquired for a sample of 15N-enriched Tag-OBD as unlabeled hRPA32C was titrated into the solution. Binding isotherms for two residues, derived from chemical shift changes induced in the Tag–OBD spectra upon addition of increasing amounts of hRPA32C (Fig. 2b), were fit to a standard single-site binding equation using the approach described previously21. An average dissociation constant (Kd) of 60 ± 18 μM was obtained from all available data. This binding constant is similar to but weaker than the Kd of 5–10 μM estimated for the interaction of hRPA32C with peptide fragments from the binding regions of the DNA repair factors XPA and UNG2 (ref. 17).

Structural model of the complex

The structures of free Tag-OBD22 and hRPA32C17 have been determined previously. These were used together with NMR chemical shift perturbations to identify the sites of interaction. Reciprocal titration experiments were carried out using 15N-enriched hRPA32C and unlabeled Tag-OBD and vice versa; the perturbed residues identify the binding surface on each molecule (Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2 online). To determine the structure of the complex, the chemical shift perturbations were used as input to guide computational docking of the two molecules. The experimental data were sufficient to define a unique relative orientation for the two domains: multiple refinements converged to a mean backbone r.m.s. deviation of 0.91 ± 0.17 Å (Table 1). The 20 lowest-energy conformers are presented in Figure 2 along with an overview of the intermolecular interface. Ramachandran analysis of the backbones of residues at the intermolecular interface shows that they continue to occupy energetically preferred conformations (Table 1). Also, pairwise backbone r.m.s. deviations from the two starting structures of <1 Å reveal that the structures of the two domains have not changed to any significant extent in the complex. The similarity of r.m.s. deviation values for the all residues versus those specifically in the interface region indicates the interface is as well defined as the rest of the structure. The absence of significant changes in the structure of the two domains is fully consistent with the modest binding-induced perturbations of the very sensitive NMR chemical shift parameter.

Table 1.

Structural statistics for the 20 representative hRPA32C–Tag-OBD conformers

| Residues used to derive ambiguous interaction restraints (AIRs)a | ||

| From hRPA32C | 8 active | 7 passive |

| From Tag-OBD | 8 active | 5 passive |

| Ramachandran analysis for residues in the interfaceb | ||

| Residues in favored and other allowed regions (%) | 82.2 | 17.7 |

| Backbone r.m.s. deviations (Å)c | ||

| From the mean, full complex | 0.91 ± 0.17 | |

| Pairwise, hRPA32C | 0.69 ± 0.14 | |

| Pairwise, Tag-OBD | 0.54 ± 0.08 | |

| Pairwise, hRPA32C versus starting structure (interface only) | 0.93 ± 0.20 (0.88 ± 0.11) | |

| Pairwise, Tag-OBD versus starting structure (interface only) | 0.85 ± 0.07 (0.79 ± 0.05) | |

| Surface area buried at the intermolecular interface (Å2) | 1,151 ± 93 | |

Structural statistics for the 20 representative conformers obtained after flexible docking with HADDOCK44 followed by refinement in explicit water using ambiguous interaction restraints derived from chemical shift perturbation data. The starting structures were single conformers from the NMR solution structure ensembles of the representative conformer for hRPA32C (PDB entry 1DPU) and the minimized average structure for Tag-OBD (PDB entry 1TBD). Cluster analysis of the structures was carried out as described in the HADDOCK44 manual (see Methods). Ramachandran analysis was carried out using PROCHECK-NMR47.

Active residues having significant NMR chemical shift perturbation and high solvent accessibility: in hRPA32C, Glu223, Asn251, Glu252, Asp260, Asp262, Thr267, Asp268 and Ala269; in Tag-OBD, Asn153, Arg154, Leu156, Thr182, Thr199, His203, His255 and Asn258. Passive residues, neighbors of the active residues that are solvent accessible: Asn226, Ser250, Gly253, Tyr256, Val259, Asp261 and Glu270; in Tag-OBD, Thr155, His201, Arg202, Arg204 and Glu254.

The interface consists of hRPA32C residues 223–226, 249–257, 259–262 and 266–270 and Tag-OBD residues 152–156, 181–182, 199–204 and 255–258.

The two C-terminal residues in hRPA32C (269 and 270) and three C-terminal residues in Tag-OBD (257–259) are not well packed into the remainder of their respective structures, and exhibit a high degree of conformational flexibility. These residues make large contributions to r.m.s. deviations, which can hide trends in the data. Consequently, these were not included in calculations of the pairwise r.m.s. deviations.

To validate the structural model, 15N-1H residual dipolar couplings (1DNH) were measured by partially aligning the samples in strained polyacrylamide gels. The 1DNH values varied from −3 to 5 Hz for hRPA32C and from −5 to 7 Hz for Tag-OBD. The ranges were sufficiently large to enable an accurate comparison to 1DNH values back-calculated from the model of the complex. There was a good fit between experimental and back-calculated data: the average r.m.s. deviation for the 20 conformers over all 65 dipolar couplings was only 1.4 Hz. Figure 2e shows a plot comparing experimental and calculated values for the representative conformer.

Tag and DNA repair factors bind to the same site on hRPA32C

In the model of the Tag-OBD–RPA32C complex, the binding surface of hRPA32C includes β-strand II, β-strand III and the loop connecting helix III and β-strand II. There is a marked similarity between the hRPA32C complex with Tag-OBD and that with the N-terminal binding region of the base excision repair factor UNG2 (ref. 17). Tyr256 is notable because it is a critical residue in the UNG2-RPA32C interface. The participation of Tyr256 in the Tag complex is clearly evident in 13C-1H HSQC NMR experiments, which reveal substantial perturbations of the aromatic protons of Tyr256 upon binding to Tag-OBD (Supplementary Fig. 3 online). Thus, the similarity between the Tag-OBD and UNG2 complexes seems to extend to specific details at the binding interface.

Although the structures of hRPA32C in these complexes are so similar, the structure of the hRPA32C-interacting region of Tag-OBD is distinct from those of the DNA repair factors. In particular, UNG2, XPA and RAD52 all interact with hRPA32C through a single helix, whereas the Tag-OBD uses a compound surface composed of extended loops (Fig. 2d). In addition to Arg154, Arg202, Arg204, Asn258 and Pro259, two histidines (His201 and His203) in Tag-OBD are in close contact with hRPA32C. There is direct experimental evidence of the presence of the histidines in the binding interface: the resonances of the His201 and His203 side chains in the 13C-1H HSQC NMR spectrum are substantially perturbed upon addition of hRPA32C to a solution of Tag-OBD (Supplementary Fig. 3 online). The distinctive character of the Tag-OBD-binding site is reflected clearly in the absence of histidines in the hRPA32C-binding sites of UNG2, XPA and Rad52 (ref. 17).

RPA32C binds to the same site on Tag-OBD as origin DNA

Detailed analysis of the structure of the complex revealed a substantial overlap between the hRPA32C-binding surface of Tag-OBD and the previously determined binding site for origin DNA. Three regions of the Tag-OBD (Phe151–Thr155, Phe183–His187 and His203–Ala207) have been shown to be essential for origin DNA–specific recognition22–25. The first indication of similarity between the hRPA32C and origin DNA–binding sites was from the analysis of chemical shift perturbations, which showed that residues in these regions of Tag-OBD shift upon addition of hRPA32C. Inspection of the model of the Tag-OBD–RPA32C complex reveals that the proposed binding site for hRPA32C extends over the top of the deep DNA-binding site.

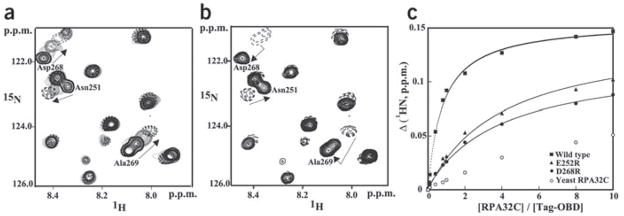

To further confirm the overlap of the binding sites of Tag-OBD and origin DNA, a competitive binding experiment was done on the complex of 15N-enriched hRPA32C and unlabeled Tag-OBD. A duplex DNA oligomer containing the SV40 origin sequence recognized by Tag, where one strand is 5′-GCAGAGGCCGA-3′, was titrated into this solution to see whether the DNA would compete hRPA32C off of the OBD. The hRPA32C signals reverted back to the position of free hRPA32C upon addition of a stoichiometric amount of DNA (compare Fig. 3a and 3b). This experiment also shows that origin DNA binds more tightly than hRPA32C, consistent with the reported Kd values for origin DNA25,26 and that noted above for hRPA32C.

Figure 3.

Effects of DNA binding and mutations on the interaction between hRPA32C and Tag-OBD. (a,b) Comparison of the binding of Tag-OBD to hRPA32C in the absence (a) and presence (b) of origin DNA. Unlabeled Tag-OBD was titrated into a 100 mM solution of 15N-enriched hRPA32C and a series of 15N,1H HSQC NMR spectra were acquired. An overlay of a small region from these spectra is shown in a. A stoichiometric amount of origin DNA duplex was then titrated into the solution and an additional spectrum was acquired (b). Arrows facilitate following the change in the location of the NMR signal. (c) NMR 1H chemical shift titration curves for the binding of wild-type, E252R, E268R and yeast hRPA32C to 15N-labeled Tag-OBD. The changes in amide proton chemical shifts of Thr199 are plotted against the ratio of Tag-OBD to hRPA32C. The line through each curve represents a best fit to the standard single-site binding equation.

Binding site mutations inhibit interaction

To test the importance of the interaction between hRPA32C domain and Tag-OBD in SV40 replication, point mutations in hRPA32C and Tag-OBD were designed based on the structure of the complex. Inspection of the surfaces of hRPA32C and Tag-OBD reveals substantial electrostatic complementarity in their binding surfaces (Fig. 2f, g). The hRPA32C surface has an acidic character, contributed primarily by Glu252, Asp261, Asp262 and Asp268. Tag-OBD has three arginines (Arg154, Arg202 and Arg204) contributing to a complementary basic surface. Salt bridges seem to form at the binding interface, such as those involving Arg154 and Arg204 of Tag-OBD with Glu252 and Asp268 of hRPA32C (Fig. 2d). The strong electrostatic component of the interaction was confirmed by a salt titration, which revealed that the complex was completely dissociated in 250 mM NaCl. Consequently, the design of mutations was based on perturbing electrostatic interactions.

The effects of mutations were first assayed by biophysical methods to verify the stability, structural integrity and binding properties of the mutant hRPA32C proteins. Characterization of alanine substitutions of hRPA32C residues Glu252, Tyr256 and Asp268 showed that each mutant retained the structure of wild-type protein, but the effect on affinity for Tag-OBD was only very modest. We reasoned that charge neutralization was insufficient because electrostatic interactions are long-range and not highly directional, so the overall effect could be dispersed through the binding interface. A much more marked effect was anticipated for charge-reversal mutants that place an opposite charge in hRPA32C’s acidic electrostatic field, and indeed, both E252R and D268R exhibited a more substantial effect on Tag-OBD binding. The binding curves for E252R and D268R demonstrate five- to ten-fold weaker binding compared with that of the wild-type hRPA32C (Kd ≅ 500 μM versus 60 μM; Fig. 3c). These results were confirmed by similar charge-neutralization and charge-reversal mutations in Tag-OBD: a modest reduction in affinity for hRPA32C was observed for R154A but a much stronger effect for R154E (Supplementary Fig. 4 online). A further test of the proposed importance of electrostatic complementarity between Tag-OBD and hRPA32C involved examining the interaction of Tag-OBD with yRPA32C, which lacks several acidic residues in the hRPA32C-binding site for Tag-OBD (Supplementary Fig. 5 online). Titration of yRPA32C into Tag-OBD revealed a substantially lower affinity than even the most perturbing of the hRPA32C charge-reversal mutations (Fig. 3c). Indeed, binding was so weak that the Kd could not be determined, consistent with the considerably lower negative charge of the Tag-OBD binding surface (Supplementary Fig. 5 online).

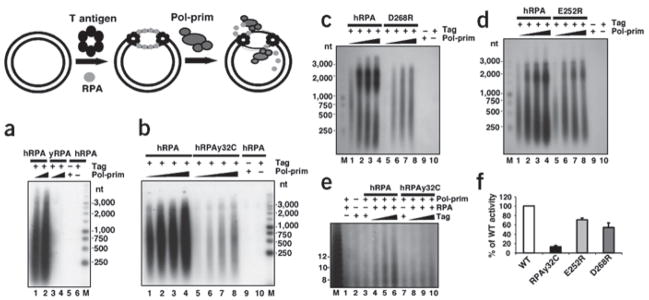

RPA32C is required for initiation of SV40 DNA replication

To further assess the functional importance of the proposed Tag-OBD interaction with hRPA32C, hRPA heterotrimers with mutations in hRPA32C were tested in SV40 DNA replication assays using the monopolymerase assay20 (Fig. 4). Human hRPA, used as a positive control in all assays, supported initiation (for example in Fig. 4a, lanes 1 and 2). As expected, yRPA exhibited no activity (lanes 3 and 4). Negative control reactions lacking either Tag or pol-prim yielded no detectable products (lanes 5 and 6). A human-yeast chimera hRPAy32C containing the winged helix-loop-helix domain from yeast hRPA in place of the human domain (Fig. 1a) retained ssDNA-binding activity and its hRPA70 subunit was active in binding to Tag (Supplementary Fig. 6 online). However, the initiation activity of hRPAy32C was diminished by an order of magnitude relative to that of hRPA in the same experiment (Fig. 4b, compare lanes 1–4 and 5–8), correlating with the weak interaction of yRPA32C with Tag-OBD observed by NMR. Initiation activity increased markedly in proportion to the amount of hRPA present in the reaction, whereas the corresponding amounts of hRPAy32C did not stimulate replication (Supplementary Fig. 6 online). The E252R mutation in hRPA32C caused a modest reduction (~20%) in activity relative to wild-type hRPA, whereas the D268R mutation substantially (~50%) impaired initiation activity (Fig. 4c,d, compare lanes 1–4 and 5–8; Supplementary Fig. 7 online), consistent with reduced binding of Tag-OBD to the corresponding hRPA32C mutants. The results demonstrate that hRPA32C serves an important function in initiation of SV40 DNA replication, and validate the structural model of the Tag-OBD–RPA32C complex (Figs. 2 and 3).

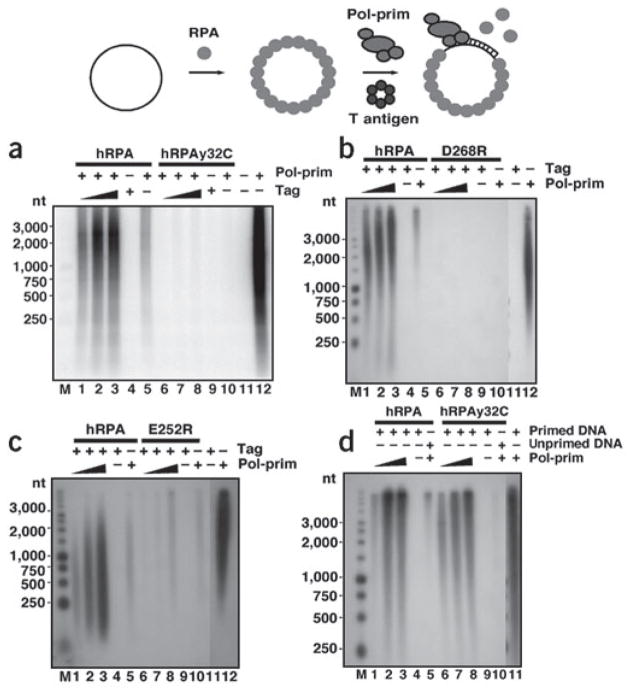

Figure 4.

Mutations in hRPA32C that weaken interaction with Tag are defective in initiation of SV40 DNA replication. (a–d) Initiation of replication was tested in monopolymerase reactions containing 200 ng of the indicated hRPA and 300 or 400 (a), or 100–400 ng (b–d), of pol-prim as indicated. Control reactions contained hRPA but lacked either pol-prim or Tag as indicated (−). The products were resolved by alkaline agarose gel electrophoresis and visualized by autoradiography. DNA size markers are indicated (M). (e) SV40 monopolymerase reactions containing radiolabeled CTP were carried out in the presence of 200 ng of the indicated hRPAs, 250 ng of pol-prim, and 250–750 ng of Tag as indicated. Control reactions lacking Tag, hRPA or pol-prim are indicated (−). Radiolabeled RNA products were resolved by electrophoresis on a polyacrylamide gel containing 20% urea and visualized by autoradiography. M, radiolabeled oligonucleotide size marker dT (4–22). Arrowhead indicates RNA primers of 8–10 nt. (f) Primer synthesis in the monopolymerase reaction was quantified and expressed as a percentage of wild-type activity. At least two reactions were used for quantification of each mutant. Brackets represent standard error.

RPA32C interaction with Tag promotes primer synthesis

Previous studies2, as well as the results presented in Figure 1, suggest that Tag interaction with hRPA is crucial for primer synthesis in initiation and in Okazaki fragment synthesis. To ask whether primer synthesis requires the Tag-RPA32C interaction, we first measured the ability of Tag to stimulate the synthesis of radiolabeled RNA primers (eight to ten nucleotides (nt)) in the SV40 monopolymerase reaction20 in the presence of wild-type or chimeric hRPA (Fig. 4e). Tag stimulated primer synthesis in the presence of hRPA (lanes 3–5) but not chimeric hRPA (lanes 6–8). Control reactions in the absence of Tag or pol-prim (lanes 1 and 2) yielded no primers. The hRPA32 point mutants E252R and D268R supported primer synthesis, but their activity was less than that of wild-type hRPA (Fig. 4f). The results indicate that Tag interaction with hRPA32C promotes priming during initiation.

To test whether the Tag-RPA32C interaction is also needed for primer synthesis at a later step after origin DNA unwinding, ssDNA presaturated with hRPA, hRPAy32C chimera or a point mutant was used as the template for priming and elongation (Fig. 5a–c). In the presence of hRPA, Tag stimulated primer synthesis and extension into labeled DNA products (lanes 1–3), whereas little or no product was detected in the presence of any of the mutant hRPAs (lanes 6–8). Abundant products were detected in the positive controls without hRPA (lanes 12) and little or no products were observed in the absence of pol-prim (lanes 4, 9 and 11) or Tag (lanes 5 and 10). Quantification of primer synthesis and extension is shown in Supplementary Figure 7 online. We conclude that interaction of Tag with hRPA32C, independent of origin DNA unwinding, is required for its ability to stimulate primer synthesis and elongation on hRPA-coated ssDNA.

Figure 5.

hRPA32C is needed for primosome activity, but not for primer extension. (a–c) Primer synthesis and extension was assayed on 100 ng M13 ssDNA precoated with 600 ng of hRPA or mutant hRPA as indicated. Reactions contained 250 ng of pol-prim and 250–750 ng of Tag as indicated. Control reactions lacked hRPA, pol-prim or Tag as indicated (−). Radiolabeled DNA products were resolved by alkaline agarose gel electrophoresis and visualized by autoradiography. M, DNA size markers as indicated. (d) Singly primed ssDNA (100 ng) precoated with 1,000 ng of the indicated hRPA was incubated with purified pol-prim (100, 150 and 250 ng) as indicated (+). Negative control reactions were done without pol-prim (lanes 4 and 9) or with unprimed template (lanes 5 and 10). Primer extension in the absence of hRPA is shown in lane 11.

The data above do not distinguish whether hRPA32C is required only for primer synthesis in the presence of Tag and pol-prim, or also for primer extension, which requires only pol-prim2,27. This question was addressed by examining the activity of pol-prim on a preprimed ssDNA template saturated with either the chimera hRPAy32C or hRPA (Fig. 5d). The primer elongation activity in the presence of human and chimeric hRPA was nearly identical (lanes 1–3 and 6–8). DNA synthesis was not detected in the absence of pol-prim or when unprimed dDNA template was coated with the same amount of mutant hRPA (lanes 4, 5, 9 and 10). Primer elongation in the absence of hRPA yielded products of smaller size (lane 11), consistent with previous evidence that hRPA enhances the processivity of DNA synthesis12,13,19,20. We conclude that both hRPAs are capable of facilitating primer elongation by pol-prim.

DISCUSSION

Taken together with the known interaction of Tag with hRPA70 (refs. 6,7,15,16), the evidence presented here suggests that each hRPA heterotrimer has two binding surfaces for Tag, one in hRPA70 and a weaker one in hRPA32C. Although the interaction of hRPA32C with Tag-OBD is of moderate affinity, characterization of the complex by NMR enabled modeling of the structure at sufficient resolution to identify critical residues involved in the binding interface. The physical interaction of hRPA32C with Tag-OBD is species-specific. Despite strong homology between yRPA and hRPA, yRPA32C does not bind Tag-OBD or support SV40 replication. Mutational analysis suggests strongly that hRPA32C interaction with Tag-OBD allows pol-prim to gain access to hRPA-coated ssDNA for primer synthesis. The reduced replication activity of hRPA32C mutants is easily detectable as the amount of hRPA is raised (Supplementary Fig. 6 online), but might not be obvious with lower amounts, providing an explanation for differences with observations reported previously16,18. Other differences include the use of purified pol-prim in the monopolymerase and primosome assays, rather than the hRPA-depleted human cell extracts used previously16,18. Because hRPA is highly abundant in vivo, our results suggest that interaction of hRPA32C and Tag-OBD is physiologically relevant. Notably, a conditional RPA32 mutant of yeast that lacks the RPA32C domain progresses slowly through S phase, loses ARS plasmids at high frequency, and is synthetically lethal with a conditional pol-prim mutant at permissive temperature28. These phenotypes imply that one or more steps in chromosomal replication may also depend on RPA32C interaction with protein partners.

hRPA32C uses a common binding site to interact with Tag-OBD and DNA repair factors17. Like Tag, XPA and Rad52 have an additional binding site in hRPA70 (refs. 29,30), although the relative importance of these contact points in DNA repair is not known. Notably, the RPA32C truncation mutant of yeast has a mutator and hyper-recombination phenotype, which suggests a role for RPA32C in DNA repair28. One of the common functions of RPA in different DNA processing pathways is the ability to facilitate the exchange of proteins on ssDNA (‘hand-off’)5,17,31 as the pathway proceeds. The promiscuity of hRPA32C in binding DNA-processing proteins, while maintaining modest affinity for its binding partner, suggests that it serves as a facilitator in the hand-off mechanism. Characterization of structural mechanisms such as hand-off presents a major challenge, but one that must be overcome to better understand fundamental DNA processing events such as replication.

Mechanism of Tag stimulation of primer synthesis

Primer synthesis but not primer elongation on hRPA-saturated ssDNA requires Tag13,14,20,27. The ability of Tag to mediate priming by pol-prim correlates with its ability to interact physically with the hRPA bound to the template, strongly suggesting that physical interactions of Tag with hRPA facilitate priming13,15. The data presented in this report and previously18 point to a functional role for hRPA32C in Tag-mediated priming.

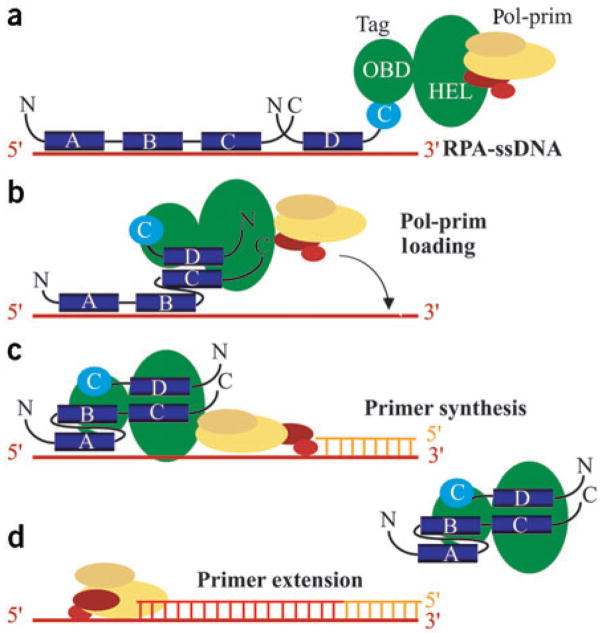

How might the physical interaction of Tag with hRPA32C facilitate primer synthesis? We postulate that Tag interacts with hRPA to facilitate its partial dissociation from ssDNA, thereby creating a short region of ssDNA accessible for primer synthesis (Fig. 6). Based on all available evidence6–8,21,27,32–37, we propose that interaction of Tag with both RPA32 and RPA70 allows it to remodel the structure of ssDNA-bound hRPA, transiently shifting it from the high affinity, extended binding mode to a weaker, more compact binding mode (Fig. 6a, b). hRPA binds to ssDNA with the high-affinity DNA-binding domains A and B at the 5′ end of the occluded ssDNA, followed by the weaker binding domains C and D at the 3′ end. The lower affinity of C and D implies that the 3′ ssDNA would be transiently accessible. Binding of Tag to hRPA32C might prolong the time window in which the 3′ site is accessible. Because Tag binds to pol-prim through its helicase domain, a single Tag hexamer may bind concurrently to hRPA and pol-prim1,2,3,4,15. Given that Tag binding to both proteins is essential for priming15, we propose that a Tag hexamer transiently associated with both hRPA and pol-prim is poised to load pol-prim onto the accessible region of ssDNA (Fig. 6b, c). Primase would thereby gain access to the free ssDNA template, permitting primer synthesis and leading to dissociation of a remodeled hRPA molecule and Tag. Subsequent primer extension on hRPA-ssDNA by pol-prim does not require Tag (Fig. 6d). The model proposed in Figure 6 is consistent with our results and a large body of published evidence, but much work remains to assess its validity.

Figure 6.

Model for SV40 primosome activity on hRPA-coated ssDNA. (a) hRPA (blue) is schematically depicted in the high-affinity 28–30 nt binding mode with all four ssDNA binding domains (A–D) bound to ssDNA. hRPA14 is omitted for simplicity. The helicase domain (HEL) of a Tag hexamer (green) can associate with a pol-prim heterotetramer2,48,49. Antibodies against Tag that specifically inhibit either hRPA binding to Tag-OBD or pol-prim binding to the helicase domain prevent primer synthesis15. (b) We suggest that primosome assembly begins when Tag-OBD associates first with hRPA32C and then with hRPA70AB, transiently creating a short stretch of unbound ssDNA. (c) In concert with this hRPA remodeling, pol-prim associated with the Tag hexamer would be poised to access the free ssDNA and begin primer synthesis. (d) Primer extension by pol-prim is likely coupled with hRPA and Tag dissociation, and followed by the RFC/PCNA-mediated switch to DNA polymerase δ50 (not shown).

To better understand the role(s) of hRPA32C in the initiation of SV40 DNA replication, it will be necessary to completely analyze all hRPA-Tag interactions. The objective is to understand their coordinated action and how they are regulated through interactions with DNA and pol-prim. The increasingly detailed knowledge of the mode of action of modular, multifunctional proteins, such as our studies of the SV40 replisome, are of considerable value because they provide an understanding of the fundamental molecular mechanisms of DNA processing machineries and the role of hRPA in guiding the succession of proteins in each pathway.

METHODS

Protein preparation

Human RPA32C was expressed and purified as described17, except that the final reverse-phase HPLC step was replaced by a gel filtration column using HiLoad 16/60 Superdex 75 (Amersham Pharmacia). Yeast RPA32C domain was cloned into the same vector (pET15b), expressed in BL21 (DE3) cells, and purified in a similar manner as hRPA32C. Tag(131–259) (Tag-OBD) was cloned into a pSV278 expression vector produced in our laboratory containing a His6-tag followed by an N-terminal MBP fusion and a thrombin cleavage site before the insert. The fusion protein was purified over Ni-NTA. After thrombin cleavage and another passage over Ni-NTA, the protein was further purified over MonoS 10/10 and HiLoad 16/60 Superdex 75 (Amersham Pharmacia). Point mutants (hRPA32C E252A, E252R, Y256A, S257A, T267A, D268A and D268R; Tag R154A and R154E) were generated by QuikChange (Stratagene) site-directed mutagenesis according to vendor protocols.

Recombinant hRPA heterotrimers were expressed in Escherichia coli and purified as described38. Single-residue substitutions in hRPA32 of the hRPA heterotrimer were introduced by QuikChange (cloning details available on request). SV40 Tag, topoisomerase I, and pol-prim were purified as described37.

Uniformly enriched 15N and 13C,15N samples were prepared in minimal medium containing 1 g l−1 15NH4Cl (CIL) and 2 g l−1 unlabeled or [13C6]glucose (CIL), respectively. The DNA duplex (sequence of one strand, 5′-GCAGAGGCCGA-3′) was purchased from Midland Certified and used without further purification.

NMR spectroscopy

All NMR samples were concentrated to 100 μM in a buffer containing 2 mM DTT, 5 mM MgCl2, and 20 mM Tris-d11 at pH 7.0. Experiments were done at 25 °C using a Bruker AVANCE 600-MHz NMR spectrometer equipped with a single axis z-gradient cryoprobe. Gradient-enhanced 15N-1H HSQC and TROSY-HSQC39 spectra were recorded with 4,000 complex points in the 1H and 200 complex points in 15N dimension. The 13C-1H HSQC spectra were acquired with 4096 × 600 complex data points. Attempts to obtain NOE distance constraints for the intermolecular interface by acquiring 13C,1H-filter-edited spectra were unsuccessful, presumably owing to the intrinsically low sensitivity of the experiments and the relatively short lifetime of the complex.

To determine Kd for the binding of hRPA32C to Tag-OBD, HSQC spectra were acquired at 12 different protein ratios. Unlabeled hRPA32C was added into a 100 μM solution of 15N-labeled Tag-OBD, starting with a molar ratio of 1:0 (labeled/unlabeled) and proceeding to a ratio of 1:10. The pH of the sample after each addition was monitored and corrected if necessary. Changes in amide proton and nitrogen chemical shifts of Thr199 and His203 were fit to a standard single-site binding equation as described21.

Residual dipolar couplings (DNH) were measured by the strain-induced gel alignment procedure40,41 using a 4% polyacrylamide gel with an inner diameter of 6 mm and a molar ratio of 1:3 (labeled/unlabeled). The gel containing sample was stretched into the NMR tube using the funnel-like device described by Bax42. DNH values were determined from the difference between one-bond 15N-1H couplings measured in the absence and presence of alignment media using a combination of HSQC and TROSY spectra. A total of 65 1DNH values were measured, 28 from hRPA32C and 37 from Tag-OBD. Back-calculations of DNH were carried out using PALES43. NMR data were processed using XWINMR (Bruker) and analyzed using FELIX2000 (Accelrys) or Sparky (http://www.cgl.ucsf.edu/home/sparky/).

Structure calculations

The structure of the complex was modeled using HADDOCK44 run on a home-built Linux cluster. Chemical shift perturbations (Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2 online) and solvent accessibility of the interacting side chains (calculated using Naccess; http://wolf.bms.umist.ac.uk/naccess) were used to generate the ambiguous interaction restraints (AIRs) with a target distance of 3.0 Å. A total of 1,500 conformers of the hRPA32C–Tag complex were generated using only the AIRs, van der Waals energy and electrostatic terms in CNS45. The 200 conformers with lowest intermolecular energies were subjected to semiflexible simulated annealing and refinement with explicit water and only backbone restraints for residues outside the interface. Residues 249–257, 259–262 and 266–270 of hRPA32C, and 152–156, 181–182, 199–204 and 255–258 of Tag-OBD were allowed to be flexible in all stages of the docking procedure. The structure of the complex is represented by the 20 lowest-energy conformers. To assess accuracy, 1DNH was back-calculated for each conformer. The r.m.s. deviation between calculated and experimental values was 1.4 Hz was with a correlation coefficient of 0.85. Structures were visualized and figures generated using MolMol46.

SV40 DNA replication (monopolymerase) assay

Reaction mixtures (20 μl) contained 250 ng of supercoiled pUC-HS plasmid DNA (2.8 kb) containing the complete SV40 origin37, 200 ng of hRPA, 300 ng of topoisomerase I, 100–400 ng of pol-prim, and 250–750 ng of Tag in initiation buffer (30 mM HEPES-KOH, pH 7.9, 7 mM magnesium acetate, 10 μM ZnCl2, 1 mM DTT, 4 mM ATP, 0.2 mM each GTP, UTP, and CTP, 0.1 mM each dGTP, dATP, and dCTP, 0.02 mM dTTP, 40 mM creatine phosphate, 40 μg ml−1 of creatine kinase) supplemented with 3 μCi of [α-32P] dTTP (3,000 Ci mmol−1; Dupont NEN). Reactions were carried out and results evaluated as described37. Primer synthesis reactions were identical except that 20 μCi of [α-32P]CTP (3,000 Ci mmol−1; Dupont NEN) was the labeled nucleotide and dNTP and the ATP-regenerating system were omitted. Products were analyzed as described37.

Tag-dependent primer synthesis and extension assays on ssDNA

The reaction mixture was identical to that in the SV40 monopolymerase assay except that the template was generally 100 ng of M13mp18 ssDNA (USB) that had been preincubated for 20 min on ice with a saturating amount of hRPA. After preincubation, the remaining components were added and the assay was completed as described for the monopolymerase assay.

Singly primed template ssDNA was prepared by mixing 4.2 pmol each of M13mp18 and a 17-mer sequencing primer (−40 primer, USB), heating at 60 °C for 2 min and annealing at room temperature. The product was purified by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis and extracted from the gel using a kit (Qiagen). The primer extension reaction was carried out as described above, except that the singly primed ssDNA was substituted for unprimed ssDNA in the preincubation with hRPA, and ribonucleotides, Tag, creatine phosphate and creatine kinase were omitted.

Coordinates

The NMR chemical shifts of have been deposited in BioMagResBank (accession code), and the coordinates have been deposited at the Protein Data Bank (accession code).

Acknowledgments

We thank S. Bhattacharya, B. Dattilo, L. Douthitt, G. Hubbell, J. Jacob, M. Karra, M. Kenny, V. Klymovych, S. Meyn, C.S. Newlon, C. Sanders, L. Schwertman, E.M. Warren, D.R. Williams and M.S. Wold for valuable advice and assistance. Accelrys provided a gift of NMR software. Financial support is gratefully acknowledged from the US National Institutes of Health for operating grants and support to the Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center and the Vanderbilt Center in Molecular Toxicology, as well as from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute Professors Program (to E.F.) and Vanderbilt University.

Footnotes

COMPETING INTERESTS STATEMENT

The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests.

Note: Supplementary information is available on the Nature Structural & Molecular Biology website.

References

- 1.Fanning E, Knippers R. Structure and function of simian virus 40 large tumor antigen. Annu Rev Biochem. 1992;61:55–85. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.61.070192.000415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bullock PA. The initiation of simian virus 40 DNA replication in vitro. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 1997;32:503–568. doi: 10.3109/10409239709082001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Simmons DT. SV40 large T antigen functions in DNA replication and transformation. Adv Virus Res. 2000;55:75–134. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3527(00)55002-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stenlund A. Initiation of DNA replication: lessons from viral initiator proteins. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:777–785. doi: 10.1038/nrm1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stauffer ME, Chazin WJ. Structural mechanisms of DNA replication, repair, and recombination. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:30915–30918. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R400015200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wold MS. Replication protein A: a heterotrimeric, single-stranded DNA-binding protein required for eukaryotic DNA metabolism. Annu Rev Biochem. 1997;66:61–92. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.66.1.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Iftode C, Daniely Y, Borowiec JA. Replication protein A (RPA): the eukaryotic SSB. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 1999;34:141–180. doi: 10.1080/10409239991209255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bochkarev A, Bochkareva E. From RPA to BRCA2: lessons from single-stranded DNA binding by the OB-fold. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2004;14:36–42. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2004.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mer G, Bochkarev A, Chazin WJ, Edwards AM. Three-dimensional structure and function of replication protein A. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2000;65:193–200. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2000.65.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weisshart K, et al. Partial proteolysis of SV40 T antigen reveals intramolecular contacts between domains and conformation changes upon hexamer assembly. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:38943–38951. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406159200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gai D, et al. Insights into the oligomeric states, conformational changes and helicase activities of SV40 large tumor antigen. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:38952–38959. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406160200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dornreiter I, et al. Interaction of DNA polymerase α-primase with cellular replication protein A and SV40 T antigen. EMBO J. 1992;11:769–776. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05110.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Melendy T, Stillman B. An interaction between replication protein A and SV40 T antigen appears essential for primosome assembly during SV40 DNA replication. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:3389–3395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Collins KL, Kelly TJ. Effects of T antigen and replication protein A on the initiation of DNA synthesis by DNA polymerase α-primase. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:2108–2115. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.4.2108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weisshart K, Taneja P, Fanning E. The replication protein A binding site in simian virus 40 (SV40) T antigen and its role in the initial steps of SV40 DNA replication. J Virol. 1998;72:9771–9781. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.12.9771-9781.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Braun KA, Lao Y, He Z, Ingles CJ, Wold MS. Role of protein-protein interactions in the function of replication protein A (RPA): RPA modulates the activity of DNA polymerase α by multiple mechanisms. Biochemistry. 1997;36:8443–8454. doi: 10.1021/bi970473r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mer G, et al. Structural basis for the recognition of DNA repair proteins UNG2, XPA, and RAD52 by replication factor A. Cell. 2000;103:449–456. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00136-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee SH, Kim DK. The role of the 34-kDa subunit of human replication protein A in simian virus 40 DNA replication in vitro. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:12801–12807. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.21.12801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kenny MK, Schlegel U, Furneaux H, Hurwitz J. The role of human single-stranded DNA binding protein and its individual subunits in simian virus 40 DNA replication. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:7693–7700. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matsumoto T, Eki T, Hurwitz J. Studies on the initiation and elongation reactions in the simian virus 40 DNA replication system. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:9712–9716. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.24.9712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arunkumar AI, Stauffer ME, Bochkareva E, Bochkarev A, Chazin WJ. Independent and coordinated functions of replication protein A tandem high affinity single-stranded DNA binding domains. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:41077–41082. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305871200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Luo X, Sanford DG, Bullock PA, Bachovchin WW. Solution structure of the origin DNA–binding domain of SV40 T-antigen. Nat Struct Biol. 1996;3:1034–1039. doi: 10.1038/nsb1296-1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wun-Kim K, et al. The DNA-binding domain of simian virus 40 tumor antigen has multiple functions. J Virol. 1993;67:7608–7611. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.12.7608-7611.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Simmons DT, Loeber G, Tegtmeyer P. Four major sequence elements of simian virus 40 large T antigen coordinate its specific and nonspecific DNA binding. J Virol. 1990;64:1973–1983. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.5.1973-1983.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bradshaw EM, et al. T antigen origin-binding domain of simian virus 40: determinants of specific DNA binding. Biochemistry. 2004;43:6928–6936. doi: 10.1021/bi030228+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Titolo S, Welchner E, White PW, Archambault J. Characterization of the DNA-binding properties of the origin-binding domain of simian virus 40 large T antigen by fluorescence anisotropy. J Virol. 2003;77:5512–5518. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.9.5512-5518.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yuzhakov A, Kelman Z, Hurwitz J, O’Donnell M. Multiple competition reactions for RPA order the assembly of the DNA polymerase δ holoenzyme. EMBO J. 1999;18:6189–6199. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.21.6189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Santocanale C, Neecke H, Longhese MP, Lucchini G, Plevani P. Mutations in the gene encoding the 34 kDa subunit of yeast replication protein A cause defective S phase progression. J Mol Biol. 1995;254:595–607. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Daughdrill GW, et al. Chemical shift changes provide evidence for overlapping single-stranded DNA- and XPA-binding sites on the 70 kDa subunit of human replication protein A. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:4176–4183. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jackson D, Dhar K, Wahl JK, Wold MS, Borgstahl GE. Analysis of the human replication protein A:Rad52 complex: evidence for crosstalk between RPA32, RPA70, Rad52 and DNA. J Mol Biol. 2002;321:133–148. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)00541-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kowalczykowski SC. Some assembly required. Nat Struct Biol. 2000;7:1087–1089. doi: 10.1038/81923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Blackwell LJ, Borowiec JA. Human replication protein A binds single-stranded DNA in two distinct complexes. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:3993–4001. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.6.3993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Blackwell LJ, Borowiec JA, Mastrangelo IA. Single-stranded-DNA binding alters human replication protein A structure and facilitates interaction with DNA-dependent protein kinase. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:4798–4807. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.9.4798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Iftode C, Borowiec JA. 5′→3′ molecular polarity of human replication protein A (RPA) binding to pseudo-origin DNA substrates. Biochemistry. 2000;39:11970–11981. doi: 10.1021/bi0005761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bastin-Shanower SA, Brill SJ. Functional analysis of the four DNA binding domains of replication protein A. The role of RPA2 in ssDNA binding. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:36446–36453. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104386200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.de Laat WL, et al. DNA-binding polarity of human replication protein A positions nucleases in nucleotide excision repair. Genes Dev. 1998;12:2598–2609. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.16.2598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ott RD, Wang Y, Fanning E. Mutational analysis of simian virus 40 T-antigen primosome activities in viral DNA replication. J Virol. 2002;76:5121–5130. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.10.5121-5130.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Henricksen LA, Umbricht CB, Wold MS. Recombinant replication protein A: expression, complex formation, and functional characterization. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:11121–11132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pervushin KV, Riek R, Wider G, Wuthrich K. Attenuated T2 relaxation by mutual cancellation of dipole-dipole coupling and chemical shift anisotropy indicates an avenue to NMR structures of very large biological macromolecules in solution. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:12366–12371. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.23.12366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sass HJ, Musco G, Stahl SJ, Wingfield PT, Grzesiek S. Solution NMR of proteins within polyacrylamide gels: diffusional properties and residual alignment by mechanical stress or embedding of oriented purple membranes. J Biomol NMR. 2000;18:303–309. doi: 10.1023/a:1026703605147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tycko R, Blanco FJ, Ishii Y. Alignment of biopolymers in strained gels: a new way to create detectable dipole-dipole couplings in high-resolution biomolecular NMR. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:9340–9349. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bax A. Weak alignment offers new NMR opportunities to study protein structure and dynamics. Protein Sci. 2003;12:1–16. doi: 10.1110/ps.0233303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zweckstetter M, Bax A. Prediction of sterically induced alignment in a dilute liquid crystalline phase: aid to protein structure determination by NMR. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:3791–3792. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dominguez C, Boelens R, Bonvin AM. HADDOCK: a protein-protein docking approach based on biochemical or biophysical information. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:1731–1737. doi: 10.1021/ja026939x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brunger AT, et al. Crystallography & NMR system: a new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr D. 1998;54:905–921. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998003254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Koradi R, Billeter M, Wuthrich K. MOLMOL: a program for display and analysis of macromolecular structures. J Mol Graph. 1996;14:51–55. 29–32. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00009-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Laskowski RA, Rullman JA, MacArthur MW, Kaptein R, Thornton JM. AQUA and PROCHECK-NMR: programs for checking the quality of protein structures solved by NMR. J Biomol NMR. 1996;8:477–486. doi: 10.1007/BF00228148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Huang SG, Weisshart K, Gilbert I, Fanning E. Stoichiometry and mechanism of assembly of SV40 T antigen complexes with the viral origin of DNA replication and DNA polymerase α-primase. Biochemistry. 1998;37:15345–15352. doi: 10.1021/bi9810959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Simmons DT, Gai D, Parsons R, Debes A, Roy R. Assembly of the replication initiation complex on SV40 origin DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:1103–1112. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Waga S, Stillman B. The DNA replication fork in eukaryotic cells. Annu Rev Biochem. 1998;67:721–751. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]