Abstract

α–Epithelial catenin (E-catenin) is an important cell–cell adhesion protein. In this study, we show that α–E-catenin also regulates intracellular traffic by binding to the dynactin complex component dynamitin. Dynactin-mediated organelle trafficking is increased in α–E-catenin−/− keratinocytes, an effect that is reversed by expression of exogenous α–E-catenin. Disruption of adherens junctions in low-calcium media does not affect dynactin-mediated traffic, indicating that α–E-catenin regulates traffic independently from its function in cell–cell adhesion. Although neither the integrity of dynactin–dynein complexes nor their association with vesicles is affected by α–E-catenin, α–E-catenin is necessary for the attenuation of microtubule-dependent trafficking by the actin cytoskeleton. Because the actin-binding domain of α–E-catenin is necessary for this regulation, we hypothesize that α–E-catenin functions as a dynamic link between the dynactin complex and actin and, thus, integrates the microtubule and actin cytoskeleton during intracellular trafficking.

Introduction

α-Catenin is an adherens junction (AJ) protein that binds to β-catenin and is necessary for AJ formation and maintenance (Hirano et al., 1992; Torres et al., 1997; Vasioukhin et al., 2000; Kobielak and Fuchs, 2004). In addition, α-catenin is also involved in the regulation of cell proliferation, and this protein is often lost in human epithelial tumors (Bullions et al., 1997; Vasioukhin et al., 2001; Lien et al., 2006; Benjamin and Nelson, 2008). It is not clear whether all of the functions of α-catenin are connected to its role in intercellular adhesion or whether it may have an additional adhesion-independent role.

Normal cellular function requires constant traffic and delivery of organelles and other membrane-limited vesicles. Vesicles can use both actin and microtubule-mediated movements, and this enables them to efficiently traverse any cytoplasmic region within the cell. The microtubule-based motor proteins dynein, kinesin 2, and kinesin Eg-5 cannot directly bind to their cargoes, and they use the dynactin protein complex for this function (Schroer, 2004). Dynactin not only links a variety of cargoes to their microtubule motors, but it is also necessary for proper organization of the microtubule cytoskeleton (Vaughan and Vallee, 1995; Quintyne et al., 1999; Askham et al., 2002; Deacon et al., 2003). The dynactin complex consists of two distinct parts: a rodlike domain, which contains Arp1 filament and actin-capping proteins and is responsible for interaction with cargo, and an elongated projection containing the p150Glued homodimer, which is responsible for interaction with motor proteins and microtubules. These two parts of dynactin are bridged by p50 dynamitin, which is critical for the assembly of the entire dynactin protein complex and its association with dynein (Schroer, 2004).

In this study, we describe a novel function for α-catenin in the regulation of dynactin-mediated intracellular trafficking. We show that dynamitin links dynactin with α–epithelial catenin (E-catenin) and that α–E-catenin negatively regulates dynactin-dependent microtubule traffic.

Results and discussion

α–E-catenin binds to dynamitin and interacts with the dynactin protein complex

To gain new insights into the mechanism of α–E-catenin function, we performed a yeast two-hybrid screen to identify novel α–E-catenin–interacting proteins. α–E-catenin contains three vinculin homology domains: VH1, VH2, and VH3 (Fig. 1 A). Although the VH1 domain is responsible for binding to β-catenin, the functional significance of the VH2 and VH3 domains is not as well understood. We used ΔVH1 α–E-catenin (291–906 aa) as a bait to screen an embryonic mouse brain cDNA library. We identified 84 individual clones, and subsequent analysis revealed that 74 of them contained cDNA encoding dynamitin (Dctn2), which is a central component of the dynactin protein complex.

Figure 1.

α–E-catenin binds to dynamitin and interacts with the dynactin protein complex. (A) Schematic of α–E-catenin containing three vinculin homology (VH) domains. Numbers indicate corresponding amino acids. (B) Interaction between dynamitin and α–E-catenin in a yeast two-hybrid assay. Cells were expressing plasmids containing Gal4 DNA–BD linked to various fragments of α–E-catenin and Gal4-AD linked to dynamitin (Dyn) or β-catenin (β-cat; positive control). (C) Interaction between dynamitin and α–E-catenin in mammalian cells. HEK 293FT cells were transfected with plasmids encoding GST and GST-linked α–E-catenin or vinculin and V5-tagged dynamitin, β-catenin (positive control), and Tbr1 (negative control). Protein extracts were pulled down (IP) with glutathione–Sepharose beads and analyzed by Western blotting (WB) with anti-V5 or anti-GST antibodies. (D) α–E-catenin associates not only with dynamitin but also with Arp1 and p150Glued proteins. GST-tagged full-length or VH2–VH3 fragments (α-cat 291–906) of α–E-catenin, V5-tagged dynamitin, and Arp1 were produced in HEK 293FT cells. GST-fused proteins were pulled down with glutathione–Sepharose beads, and protein complexes were analyzed by blotting with anti-V5, anti-p150Glued, and anti-GST antibodies. (E) α–E-catenin partially cofractionates with dynactin. Total keratinocyte extracts were sedimented on sucrose gradient, and fractions were analyzed by blotting with anti-p150Glued, anti–dynein intermediate chain (DIC), antidynamitin, anti-Arp1, and anti–α-catenin antibodies. (F) Interaction between endogenous α–E-catenin and dynactin. Dynactin-containing fractions after sucrose sedimentation of total extracts from wild-type (WT) and α–E-catenin−/− (KO) cells were immunoprecipitated with anti–α-catenin (C terminal) or β-galactosidase (β-gal; control) antibodies and analyzed by blotting with anti-p150Glued, antidynamitin (Dyn), anti-Arp1, and anti–α-catenin antibodies. M, position of a molecular weight standard band in the marker lane. (G) Interaction between endogenous α–E-catenin and dynamitin. Total proteins (input) from wild-type and α–E-catenin−/− keratinocytes were immunoprecipitated with anti–α-catenin (IP–α-cat; N terminal) antibodies and analyzed by blotting with antidynamitin and anti–α-catenin antibodies.

To confirm the binding and determine the domain of α–E-catenin responsible for interaction, we performed a targeted yeast two-hybrid assay with full-length or fragments of α–E-catenin (Fig. 1 B). Dynamitin showed a strong interaction with VH2 and VH2–VH3 fragments of α–E-catenin. Interestingly, the VH1 domain displayed an inhibitory effect for this interaction, as we found a significantly weaker interaction between dynamitin and full-length α–E-catenin. Consistent with yeast two-hybrid results, we found that dynamitin interacts with full-length α–E-catenin and its VH2 domain in mammalian cells (Fig. 1 C). Interestingly, the α–E-catenin–like protein vinculin did not bind dynamitin in this assay, indicating that the α–E-catenin–dynamitin interaction is very specific (Fig. 1 C). Thus, we conclude that α–E-catenin binds to dynamitin, and the VH2 domain of α–E-catenin is responsible for this interaction.

To determine whether α–E-catenin can use dynamitin to bind to the entire dynactin complex, we analyzed α–E-catenin immunoprecipitates for the presence of other members of the dynactin complex such as Arp1 and p150Glued (Fig. 1 D). We found that full-length and VH2–VH3 domain–containing fragments of α–E-catenin pulled down not only dynamitin but also Arp1 and p150Glued proteins. Thus, not only dynamitin but also other members of the dynactin protein complex interact with α–E-catenin.

To analyze the interaction between endogenous α–E-catenin and dynactin, we performed cosedimentation and immunoprecipitation (IP) experiments. We isolated the dynactin protein complex from primary mouse keratinocytes using sucrose gradient centrifugation (Fig. 1 E). Similar to dynein, only a fraction of α–E-catenin cosedimented with dynactin (Fig. 1 E). To determine whether endogenous α–E-catenin physically interacts with dynactin, we used the fractions containing dynactin for co-IP experiments. Anti-α–E-catenin antibodies, but not the control anti–β-galactosidase antibodies, pulled down the dynactin proteins dynamitin, Arp1, and p150Glued from wild-type but not from α–E-catenin−/− keratinocytes (Fig. 1 F). In addition, an antibody directed against a different domain of α–E-catenin was able to co-IP dynamitin from keratinocyte total protein extracts (Fig. 1 G).

To determine whether α–E-catenin can potentially link cadherin–catenin complexes to dynactin, we analyzed whether α–E-catenin could simultaneously interact with β-catenin and dynamitin. We found that GST-dynamitin pulled down α–E-catenin but not the α–E-catenin–β-catenin complexes (Fig. S1 A, available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200805041/DC1). Similarly, GST–β-catenin pulled down α–E-catenin but not the α–E-catenin–dynamitin complexes (Fig. S1 B). Overall, we conclude that α–E-catenin, but not α–E-catenin–β-catenin heterodimers, binds to dynactin.

α–E-catenin and dynamitin are necessary to extend the microtubule cytoskeleton to the cell periphery and establish strong intercellular adhesion

To determine localization of α–E-catenin and dynamitin in wild-type and α–E-catenin−/− keratinocytes, we performed immunofluorescence stainings. α–E-catenin prominently localized around the nuclei and at AJs in wild-type keratinocytes (Fig. 2 A′). Dynamitin colocalized with α–E-catenin around cell nuclei, and small amounts of dynamitin were found at the cell periphery and AJs (Fig. 2 A). In contrast, dynamitin was localized almost exclusively around the nucleus in α–E-catenin−/− cells, with very little amounts of dynamitin present at the cell periphery (Fig. 2, B and B‴). These data suggest that α–E-catenin is necessary to localize dynamitin to cell edges.

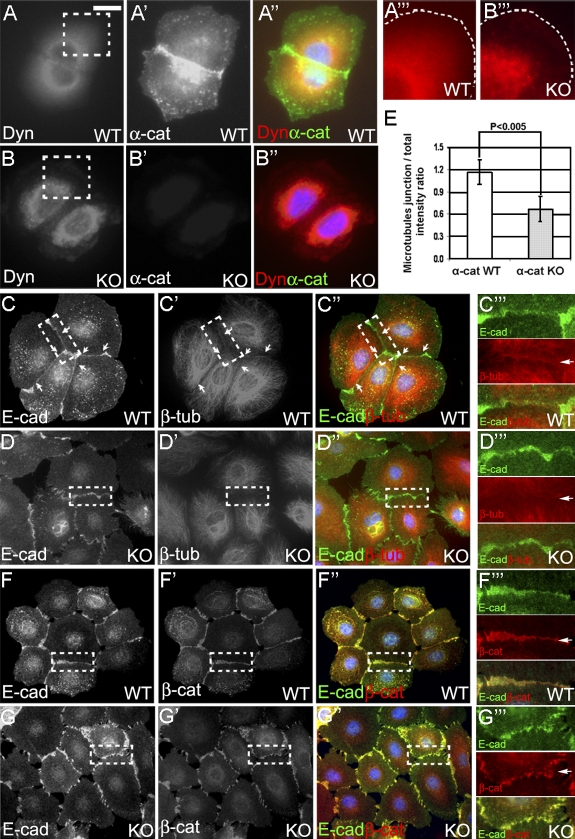

Figure 2.

α–E-catenin is necessary to extend dynactin and the microtubule cytoskeleton to the cell periphery and localize microtubules to the AJs. (A and B) Immunofluorescence staining of wild-type (WT) and α–E-catenin−/− (KO) cells with antidynamitin (Dyn) and anti–α-catenin (α-cat) antibodies. Regions in dashed boxes are shown at higher magnifications in A‴ and B‴. The cell edges are outlined with white dashed lines. (C and D) Immunofluorescence staining of wild-type and α–E-catenin−/− cells with anti–E-cadherin (E-cad) and anti–β-tubulin (β-tub) antibodies. Regions containing cell–cell junctions (dashed boxes) are shown at higher magnifications in C‴ and D‴. (E) Quantitation of microtubule accumulation at cell–cell junctions. Pairs of contacting cells displaying accumulation of E-cadherin at cell–cell borders were randomly selected. The levels of cell border accumulation of microtubules are expressed as ratios of the mean β-tubulin staining intensity at cell–cell junctions over the mean total β-tubulin intensity within two contacting cells. Each bar represents the mean value; n = 50. The p-value was determined by a t test. The error bars represent standard deviation. (F and G) β-Catenin localizes to AJs in α–E-catenin−/− cells. Immunofluorescence staining of wild-type and α–E-catenin−/− cells with anti–E-cadherin and anti–β-catenin (β-cat) antibodies. Regions containing cell–cell junctions (dashed boxes) are shown at higher magnifications in F‴ and G‴. Arrows denote the positions of the AJs. Bars: (A–A″ and B–B″) 16 μm; (A‴ and B‴) 8 μm; (C–C″, D–D″, F–F″, and G–G″) 30 μm; (C‴, D‴, F‴, and G‴) 13 μm.

It has been recently demonstrated that α–E-catenin is involved in the regulation of microtubule cytoskeleton (Shtutman et al., 2008). Staining with anti–β-tubulin antibodies revealed that the microtubules extended to the cell periphery and prominently localized to AJs in wild-type but not in α–E-catenin−/− keratinocytes (Fig. 2, C–E; arrows). This was despite the fact that β-catenin, which was previously implicated in the connection between AJs and microtubules (Ligon et al., 2001), continued to localize to cell–cell contacts in α–E-catenin−/− cells (Fig. 2, F–G‴). Thus, we conclude that α–E-catenin is necessary for proper intracellular localization of dynamitin and extension of microtubule cytoskeleton to the cell periphery and AJs.

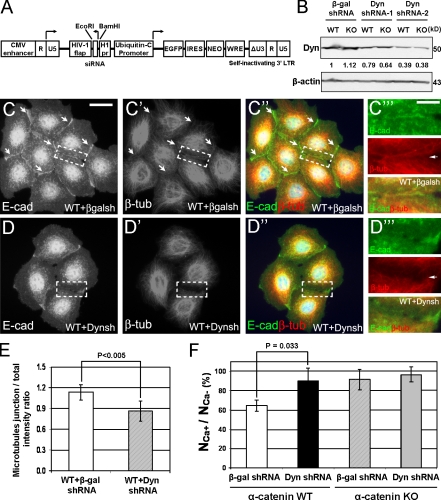

To determine whether loss of dynamitin may phenocopy the phenotype in α–E-catenin−/− cells, we used a short hairpin RNA (shRNA) knockdown (KD) approach. Because dynamitin is critical for cell mitosis, dynamitin KD cells displayed a decrease but not a complete loss of dynamitin (Fig. 3, A and B). Nevertheless, similar to α–E-catenin−/− cells, dynamitin KD cells failed to extend the microtubule cytoskeleton to the cell periphery and AJs (Fig. 3, C–E). In addition, dynamitin KD cells displayed a prominent defect in short-term Ca2+-mediated cell–cell adhesion (Fig. 3 F). Thus, dynamitin KD cells displayed the defects in organization of the microtubule cytoskeleton and strengthening of cell–cell adhesion, which were similar to the phenotypes of α–E-catenin−/− cells. We propose that interaction between α–E-catenin and dynactin may facilitate dynactin function in the extension of the microtubule cytoskeleton to the cell periphery, and this can promote cell–cell junction formation.

Figure 3.

Dynamitin is necessary to extend the microtubule cytoskeleton to the cell periphery and AJs and establish strong cell–cell adhesion. (A) Schematic model of a lentiviral shRNA vector used for the generation of dynamitin KD cells. CMV, cytomegalovirus; LTR, long terminal repeat. (B) Total protein extracts from wild-type (WT) and α–E-catenin−/− (KO) cells transduced with β-galactosidase (β-gal; control) and dynamitin (Dyn; constructs 1 and 2) shRNA lentiviruses analyzed by blotting with antidynamitin (Dyn) and anti–β-actin antibodies. Numbers represent relative levels of dynamitin. (C and D) Dynamitin is necessary to localize microtubules to AJs. Wild-type keratinocytes transduced with β-galactosidase shRNA (β-galsh; C) or dynamitin shRNA-2 (Dynsh; D) were analyzed by immunostaining with anti–E-cadherin (E-cad) and anti–β-tubulin (β-tub) antibodies. Regions containing cell–cell junctions (dashed boxes) are shown at higher magnifications in C‴ and D‴. Note the prominent localization of microtubules to AJs in β-galactosidase shRNA cells (arrows) but not in dynamitin KD cells. (E) Quantitation of junctional localization of microtubules in control (WT + β-gal shRNA) and dynamitin KD (WT + Dyn shRNA) cells. Quantitation was performed as described in Fig. 2 E. n = 50. (F) dynamitin KD cells display cell–cell adhesion defects. Wild-type and α–E-catenin−/− keratinocytes expressing β-galactosidase shRNA or dynamitin shRNA-2 were allowed to aggregate for 1 h with and without Ca2+, and the total number of particles was counted. The degree of Ca2+-dependent cell aggregation (NCa+/NCa− percentage) was measured as a percentage of the decrease in the particle numbers in Ca2+-containing versus Ca2+-free conditions. Bars represent mean values; n = 3. The p-value was determined by t test. The error bars represent standard deviation. Bars: (C–C″ and D–D″) 28 μm; (C‴ and D‴) 11.2 μm.

α–E-catenin impacts dynactin-mediated intracellular traffic in an adhesion-independent manner

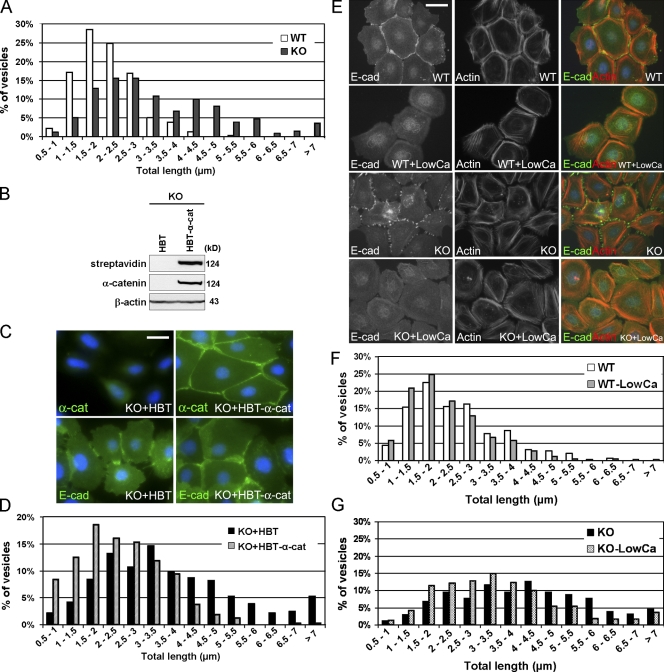

The primary function of dynactin is to facilitate the microtubule motor–mediated traffic of cell organelles and vesicles (Schroer, 2004). To examine whether α–E-catenin may be involved in regulation of dynactin-dependent traffic, we performed analyses of lysosome movement in live wild-type and α–E-catenin−/− cells. We labeled lysosomes with LysoTracker dye and followed their movements using time-lapse microscopy (n ≥ 10; Videos 1 and 2, available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200805041/DC1). Software-mediated quantitation of the total length of movement over 300 individual lysosomes from 15–20 randomly selected cells of each genotype showed a significant increase in the distances traveled by lysosomes in α–E-catenin−/− cells (Fig. 4 A). This defect was rescued by expression of exogenous α–E-catenin in α–E-catenin−/− cells (n ≥ 8; Fig. 4, B–D; and Videos 3 and 4). Thus, we conclude that α–E-catenin negatively impacts dynactin-dependent microtubule traffic and that organelle motility is increased in α–E-catenin−/− cells.

Figure 4.

α–E-catenin negatively regulates dynactin-mediated intracellular traffic in an AJ-independent manner. (A) Quantitation of lysosome movements in wild-type (WT) and α–E-catenin−/− (KO) keratinocytes. The total length of lysosome movements within 5 min was determined using Imaris software analysis of the time-lapse videos. Bars represent the percentage of the vesicles that moved over the indicated distances; n = 315 for wild type and n = 342 for α–E-catenin−/−. Note the prominent increase in lysosome motility in α–E-catenin−/− cells. (B and C) Expression of exogenous α–E-catenin in α–E-catenin−/− cells. Keratinocytes were transduced with retroviruses expressing the HBT tag (HBT) or HBT-tagged α–E-catenin (HBT–α-cat) and analyzed by blotting (B) and immunostaining (C) with streptavidin or anti–α-catenin (α-cat), anti–β-actin, and anti–E-cadherin (E-cad) antibodies. (D) Reexpression of α–E-catenin in α–E-catenin−/− cells rescues lysosome motility defects. Quantitation of lysosome movements in α–E-catenin−/− keratinocytes expressing HBT (KO + HBT) or HBT-α–E-catenin (KO + HBT–α-cat). n = 354 for KO + HBT and n = 318 for KO + HBT–α-cat. (E) Disruption of AJs in keratinocytes cultured in low-calcium media. Immunofluorescence staining of wild-type and α–E-catenin−/− cells incubated in normal or low-calcium (LowCa) media with anti–E-cadherin (green) antibodies and phalloidin (actin; red). (F and G) Quantitation of lysosome movements in wild-type (F) and α–E-catenin−/− (G) keratinocytes incubated in normal or low-calcium media. n = 319 for WT, n = 326 for WT + LowCa, n = 307 for KO, and n = 347 for KO + LowCa. Bars: (C) 25 μm; (E) 33 μm.

α-Catenin is necessary for the AJ's formation, and α–E-catenin−/− keratinocytes display prominent AJ defects (Vasioukhin et al., 2000). To distinguish between AJ-dependent and α–E-catenin–dependent phenotypes, we analyzed potential changes in dynactin-mediated organelle traffic in cells that maintained α–E-catenin but were unable to form AJs. For this purpose, we analyzed lysosome traffic in keratinocytes cultured in low-calcium media, which cannot support the formation of AJs (Fig. 4 E). Interestingly, analyses of lysosome movements in the cells cultured in low-calcium media did not reveal significant changes in lysosome traffic (n ≥ 9 for each cell type and condition; Fig. 4, F and G; and Videos 1, 2, 5, and 6, available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200805041/DC1). Thus, we conclude that an increase in the lysosome traffic in α–E-catenin−/− keratinocytes is an α–E-catenin–dependent but not an AJ-dependent phenotype, indicating that the function of α–E-catenin in the regulation of dynactin-mediated traffic is AJ independent.

α–E-catenin is necessary for the functional connection between dynactin-mediated organelle traffic and the actin cytoskeleton

α–E-catenin could potentially regulate dynactin-mediated traffic by interfering with the assembly of dynactin–dynein protein complexes or their interaction with cargo. This was unlikely because the composition of the dynactin–dynein protein complexes did not change significantly in α–E-catenin−/− cells (Fig. S2, A and B, available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200805041/DC1). Moreover, we did not find an increase in the association between dynein–dynactin and the vesicles in α–E-catenin−/− cells (Fig. S2 C).

Cellular organelles and vesicles can use both actin filaments and microtubules for intracellular transport. Usually, microtubules are used for rapid long-range movements, and actin is used for short-range movements. Because vesicles can constantly switch between actin filaments and microtubules, the disruption of actin filaments often results in a significant increase in the mobility of vesicles and organelles (Cordonnier et al., 2001). We analyzed whether the integrity of the actin cytoskeleton is disrupted in α–E-catenin−/− cells. Staining for filamentous actin (F-actin) revealed the presence of well-organized F-actin bundles in α–E-catenin−/− cells (Fig. 5, A and B). We conclude that the organization of actin filaments is not disrupted in α–E-catenin−/− cells, and, thus, this cannot explain stimulation in dynactin-dependent traffic in α–E-catenin−/− keratinocytes.

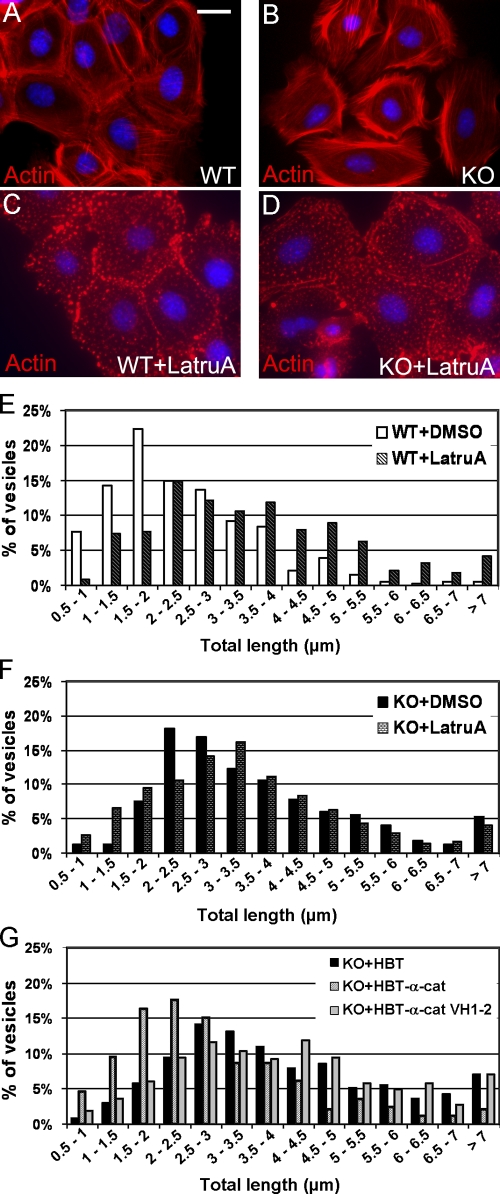

Figure 5.

α–E-catenin is necessary to couple dynactin-mediated organelle traffic and the actin cytoskeleton. (A–D) Prominent actin cytoskeletons in wild-type (WT; A) and α–E-catenin−/− (KO; B) keratinocytes and their disruption by latrunculin A treatment (C and D). Immunofluorescence staining with phalloidin. (E and F) Quantitation of lysosome motility in wild-type (E) and α–E-catenin−/− (F) keratinocytes treated with latrunculin A (+LatruA) or DMSO control. Note that the disruption of the actin cytoskeleton significantly accelerates lysosome motility in wild-type cells (E) but has only a minor impact in α–E-catenin−/− cells (F). n = 336 for WT + DMSO, n = 337 for WT + LatruA, n = 319 for KO + DMSO, and n = 347 for KO + LatruA. (G) Quantitation of lysosome motility in α–E-catenin−/− cells expressing the HBT tag, full-length (HBT–α-cat), or VH1–VH2 fragment (HBT–α-cat VH1–2) of α–E-catenin. n = 326 for KO + HBT, n = 323 for KO + HBT–α-cat, and n = 327 for KO + HBT–α-cat VH1–2. Note the decrease in lysosome motility in cells expressing full-length but not truncated α–E-catenin. Quantitation was performed as described in Fig. 4 A. Bar, 23 μm.

Because α–E-catenin is known to engage the actin cytoskeleton, we hypothesized that it may be involved in the functional linking of the dynactin complex with the actin cytoskeleton. In this case, α–E-catenin−/− cells should display an increase in the motility of dynactin cargoes, and this increase should not be further enhanced by disruption of the actin cytoskeleton. We already found that α–E-catenin−/− cells display an increase in dynactin-mediated organelle motility (Fig. 4 A). To determine the impact of the actin cytoskeleton, we performed quantitation of lysosome movement in cells treated with latrunculin A, which depolymerizes actin filaments (Fig. 5, C–F). As previously reported, treatment with latrunculin A resulted in a significant increase in the mobility of the lysosomes in wild-type cells (n ≥ 9; Fig. 5 E and Video 7, available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200805041/DC1; Cordonnier et al., 2001). Remarkably, latrunculin A treatment of α–E-catenin−/− cells did not significantly increase lysosome movements (n ≥ 12; Fig. 5 F and Video 8). The overall motility of lysosomes in vehicle-treated α–E-catenin−/− cells was similar to the motility of lysosomes in wild-type cells treated with latrunculin A (Fig. 5, E and F). Interestingly, although expression of full-length α–E-catenin rescued the lysosome movement defect in α–E-catenin−/− cells, expression of truncated α–E-catenin lacking its actin-binding domain (BD) had no effect (Fig. 5 G, Fig. S3, and Video 9), indicating that the actin-BD was necessary for α–E-catenin function in the regulation of lysosome traffic. Thus, we conclude that α–E-catenin is required for the functional connection between the dynactin-mediated organelle traffic and the actin cytoskeleton.

To summarize, we report in this study that α–E-catenin binds to dynactin and regulates its function. The regulation of dynactin activities is a novel and previously unrecognized function of α–E-catenin, and future research will be necessary to explore the details of α–E-catenin function in the regulation of both the dynactin-mediated extension of the microtubule cytoskeleton to the cell periphery and dynactin-mediated intracellular transport events.

Materials and methods

Cells and cell–cell adhesion assays

Primary keratinocytes were cultured from newborn mouse skin as described previously (Vasioukhin et al., 2001). To obtain α–E-catenin−/− and control keratinocytes, the α–E-cateninflox/flox cells were treated with Cre- and GFP-carrying adenoviruses, respectively (MOI 10; Vector Laboratories). Loss of α–E-catenin in Cre-adenovirus–treated cells was verified by Western blotting and immunofluorescence. Human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293FT cells were purchased from Invitrogen and were grown in 5% CO2 in Dulbecco's modified essential medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum and antibiotics.

Cadherin-dependent cell–cell adhesion assays were performed as described previously (Takeichi and Nakagawa, 1998). Particles were counted with a particle counter (Z1 Coulter Counter; Beckman Coulter).

Generation of expression constructs

Details of expression plasmids can be found in Table I. Murine α–E-catenin, β-catenin, dynamitin, vinculin, Tbr1, and Arp1 sequences were amplified from mouse brain or keratinocyte cDNA using Pfu polymerase (Agilent Technologies) and cloned into the gateway entry vector pCR8/GW/TOPO (Invitrogen). Gateway technology was used to generate GST- (pDEST27) or V5 (pcDNA3.1/nV5-DEST)-tagged expression constructs for eukaryotic expression and activating domain– (AD; pDEST22) and BD (pDEST32)-tagged constructs for two-hybrid analysis. Retroviral α–E-catenin expression vectors were generated by cloning α–E-catenin into the XbaI–EcoRI sites of the pQCXIP–histidine-biotin tag (HBT) vector containing N-terminal HBT (provided by P. Kaiser, University of California, Irvine, Irvine, CA; Tagwerker et al., 2006). Retroviruses were produced using the Phoenix system (provided by G. Nolan, Stanford University, Stanford, CA; Swift et al., 2001).

Table I. Plasmids used in this study.

| Construct name | Tag | Primer sequence | Vector |

|---|---|---|---|

| BD–α-cat 1–906 | BD | Forward, 5′-GGCGAGATCTCCATGACTGCCGTCCACGCAG-3′ | pDEST32 |

| Reverse, 5′-GGCGAGATCTCAGATGCTGTCCATGGCTTT-3′ | |||

| GST–α-cat 1–906 | GST | Forward, 5′-GGCGAGATCTCCATGACTGCCGTCCACGCAG-3′ | pDEST27 |

| Reverse, 5′-GGCGAGATCTCAGATGCTGTCCATGGCTTT-3′ | |||

| BD–α-cat 1–290 | BD | Forward, 5′-GGCGAGATCTCCATGACTGCCGTCCACGCAG-3′ | pDEST32 |

| Reverse, 5′-TCAAATGATTTGTTTATCAAAGTTGTTG-3′ | |||

| GST–α-cat 1–290 | GST | Forward, 5′-GGCGAGATCTCCATGACTGCCGTCCACGCAG-3′ | pDEST27 |

| Reverse, 5′-TCAAATGATTTGTTTATCAAAGTTGTTG-3′ | |||

| BD–α-cat 291–651 | BD | Forward, 5′-ATTATGGACCCCTTGAGCTTC-3′ | pDEST32 |

| Reverse, 5′-TCATCTGACATCAAAGTCTTCAGTC-3′ | |||

| GST–α-cat 291–651 | GST | Forward, 5′-ATTATGGACCCCTTGAGCTTC-3′ | pDEST27 |

| Reverse, 5′-TCATCTGACATCAAAGTCTTCAGTC-3′ | |||

| BD–α-cat 652–906 | BD | Forward, 5′-ACCATGGTCAGAAGCAGGACCAGTGT-3′ | pDEST32 |

| Reverse, 5′-GGCGAGATCTCAGATGCTGTCCATGGCTTT-3′ | |||

| GST–α-cat 652–906 | GST | Forward, 5′-ACCATGGTCAGAAGCAGGACCAGTGT-3′ | pDEST27 |

| Reverse, 5′-GGCGAGATCTCAGATGCTGTCCATGGCTTT-3′ | |||

| BD–α-cat 1–651 | BD | Forward, 5′-GGCGAGATCTCCATGACTGCCGTCCACGCAG-3′ | pDEST32 |

| Reverse, 5′-TCATCTGACATCAAAGTCTTCAGTC-3′ | |||

| GST–α-cat 1–651 | GST | Forward, 5′-GGCGAGATCTCCATGACTGCCGTCCACGCAG-3′ | pDEST27 |

| Reverse, 5′-TCATCTGACATCAAAGTCTTCAGTC-3′ | |||

| BD–α-cat 291–906 | BD | Forward, 5′-ATTATGGACCCCTTGAGCTTC-3′ | pDEST32 |

| Reverse, 5′-GGCGAGATCTCAGATGCTGTCCATGGCTTT-3′ | |||

| GST–α-cat 291–906 | GST | Forward, 5′-ATTATGGACCCCTTGAGCTTC-3′ | pDEST27 |

| Reverse, 5′-GGCGAGATCTCAGATGCTGTCCATGGCTTT-3′ | |||

| AD–β-cat | AD | Forward, 5′-CGAGGATCCGCAATTGCAATGGCTACTCAAGCTGAC-3′ | pDEST22 |

| Reverse, 5′-GAGGATCCCAATTGTTACAGGTCAGTATCAAACC-3′ | |||

| V5–β-cat | V5 | Forward, 5′-CGAGGATCCGCAATTGCAATGGCTACTCAAGCTGAC-3′ | pcDNA3.1/nV5-DEST |

| Reverse, 5′-GAGGATCCCAATTGTTACAGGTCAGTATCAAACC-3′ | |||

| AD-Dyn | AD | Forward, 5′-GCCATGGCGGACCCTAAATA-3′ | pDEST22 |

| Reverse, 5′-TCACTTTCCCAGCCTCTTC-3′ | |||

| V5-Dyn | V5 | Forward, 5′-GCCATGGCGGACCCTAAATA-3′ | pcDNA3.1/nV5-DEST |

| Reverse, 5′-TCACTTTCCCAGCCTCTTC-3′ | |||

| V5-Tbr1 | V5 | Forward, 5′-GCTATGCAGCTGGAGCATTGCCTC-3′ | pcDNA3.1/nV5-DEST |

| Reverse, 5′-GCTGTGCGAGTAGAAGCCATAGTA-3′ | |||

| V5-Arp1 | V5 | Forward, 5′-ATGGAGTCCTACGATGTGATC-3′ | pcDNA3.1/nV5-DEST |

| Reverse, 5′-TTAGAAGGTTTTCCTGTGGATG-3′ | |||

| GST-Dyn | GST | Forward, 5′-GCGGATCCATGGCGGACCCTAAATACG-3′ | pGEX-6P |

| Reverse, 5′-GCGAATTCTCACTTTCCCAGCCTCTTC-3′ | |||

| GST-vinculin | GST | Forward, 5′-GCGATGCCGGTGTTTCACA-3′ | pDEST27 |

| Reverse, 5′-CTACTGGTACCAGGGAGTC-3′ | |||

| HBT–α-cat | HBT | Forward, 5′-TCTAGAATGACTGCCGTCCACGCAG-3′ | PQCXIP-HBT |

| Reverse, 5′-GAATTCTCAGATGCTGTCCATGGCT-3′ | |||

| HBT–α-cat VH1–VH2 | HBT | Forward, 5′-TCTAGAATGACTGCCGTCCACGCAG-3′ | PQCXIP-HBT |

| Reverse, 5′-CGGAATTCTCATCTGACATCAAAGTCTTCAGTC-3′ |

cat, catenin; Dyn, dynamitin.

To generate the lentiviral vector for production of shRNA, the FUGW vector (provided by D. Baltimore, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA; Lois et al., 2002) was modified by placing internal ribosome entry site–neomycin sequences downstream from EGFP and cloning of human H1 promoter followed by unique BamHI–EcoRI sites upstream from the ubiquitin promoter (Fig. 3 A). For the generation of dynamitin KD constructs, sense and antisense oligonucleotides were annealed and ligated into the BamHI–EcoRI sites of the FUGW-H1-GFP-neomycin vector. Oligonucleotides 5′-GATCCGGCAGAAGTACCAACGACTACTTTCAAGAGAAGTAGTCGTTGGTACTTCTGCTTTTTGG-3′ and 5′-AATTCCAAAAAGCAGAAGTACCAACGACTACTTCTCTTGAAAGTAGTCGTTGGTACTTCTGCCG-3′ were used for dynamitin shRNA construct 1, and oligonucleotides 5′-GATCCGGGATGATCAAGCAGAGTTTGATTCAAGAGATCAAACTCTGCTTGATCATCCTTTTTGG-3′ and 5′-AATTCCAAAAAGGATGATCAAGCAGAGTTTGATCTCTTGAATCAAACTCTGCTTGATCATCCCG-3′ were used for dynamitin shRNA construct 2. The lentiviruses were produced in HEK 293FT cells as described previously (Lois et al., 2002). All PCR-generated inserts and shRNA constructs were verified by sequencing.

Yeast two-hybrid analysis and GST pull-down experiments in HEK 293FT cells

The two-hybrid system (ProQuest; Invitrogen) was used as recommended by the manufacturer. The mouse embryonic brain ProQuest yeast two-hybrid cDNA library in the pEXP-AD502 vector was custom made from total RNA isolated from pooled embryonic day 12.5–16.5 mouse embryonic brains (Invitrogen).

HEK 293FT cells were cotransfected with the indicated plasmids and lysed in a buffer containing 0.5% NP-40, 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, and a cocktail of protease inhibitors (Roche). Cell lysates were incubated with 50 μl of 50% glutathione-agarose (Thermo Fisher Scientific) at 4°C for 1 h, beads were washed three times with lysis buffer, and the proteins were released by heating in lithium dodecyl sulfate loading buffer.

Expression of recombinant proteins and in vitro GST pull-down assays

His-tagged α–E-catenin was expressed in Escherichia coli M15 and purified as previously described (Aberle et al., 1994). The His-tagged construct was obtained from W.I. Weis (Stanford University, Stanford, CA). Full-length mouse β-catenin (provided by M. Duñach, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Bellaterra, Spain; Roura et al., 1999) and dynamitin proteins were expressed as GST fusion proteins using pGEX-6P vectors (GE Healthcare). Proteins were expressed in E. coli BL21 and purified with glutathione–Sepharose beads as described by the manufacturer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). GST tags were removed by PreScission protease (GE Healthcare).

Glutathione–Sepharose beads prebound with 10 μg of GST-tagged proteins were incubated at 4°C for 2 h with 10 μg of purified recombinant proteins in a buffer containing 1× PBS, 0.2% NP-40, 10% glycerol, 2 mM MgCl2, and a cocktail of protease inhibitors. After incubation, beads were washed three times with incubation buffer, and the proteins were released by heating in lithium dodecyl sulfate loading buffer.

Immunofluorescence microscopy and quantitation of junctional microtubules

For immunostainings, cells were seeded on Chamber slides (Lab-Tek) coated with collagen-I. Cells were fixed in 4% formaldehyde/PBS for 5 min at 37°C before double immunostaining and analysis at room temperature using a microscope (TE 200; Nikon) equipped with PlanFluor ELWD 40× NA 0.60 and 60× NA 0.70 objectives and a digital camera (CoolSNAP HQ; Photometrics) controlled by MetaMorph software (MDS Analytical Technologies). Primary antibodies against dynamitin (1:100; BD), α-catenin (1:500, Sigma-Aldrich), β-catenin (1:500; Sigma-Aldrich), epithelial cadherin (E-cadherin; 1:500; Invitrogen), and β-tubulin (1:200; Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank) were followed by FITC- or Texas red–conjugated secondary antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories). F-actin was detected by staining with phalloidin–Texas red (1:300; Sigma-Aldrich). Differences in junctional staining for microtubules were quantified as described previously (Chen et al., 2003).

Sucrose gradient centrifugation, IP, Western blotting, and membrane flotation assay

Total keratinocyte lysates were fractionated on 5–40% sucrose gradients as described previously (Berrueta et al., 1999). BSA (4S), yeast alcohol dehydrogenase (7S), and thyroglobulin (19S) were used as sedimentation standards.

For IP, the cells were lysed in IP buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 1% Triton X-100, 100 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM MgCl2, 10% glycerol, 20 mM sodium fluoride, 10 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 1 mM sodium vanadate, and a cocktail of protease inhibitors. Total lysates were precleaned with 30 μl of 50% protein A/G–Sepharose beads (preblocked with 20% BSA; Thermo Fisher Scientific) and incubated with anti–α-catenin (Epitomics) for 2 h at 4°C followed by a 1-h incubation with 50 μl of 50% protein A/G–Sepharose beads. Sepharose beads were washed four times with IP buffer and analyzed by Western blotting. For IPs from the fraction of sucrose gradient sedimentation, the proteins were pulled down with anti–α-catenin (Sigma-Aldrich) or anti–β-galactosidase (Rockland) antibodies and protein A–Sepharose beads (GE Healthcare), washed with PBS, and analyzed by Western blotting with antidynamitin (1:1,000; BD), anti-p150Glued (1:1,000; BD), anti-Arp1 (1:1,000; Abcam), anti–α-catenin (1:1,000; Sigma-Aldrich), anti-V5 (1:5,000; AbD Serotec), anti-GST (1:1,000; ABM), anti–β-catenin (1:2,000; Sigma-Aldrich), anti–dynein intermediate chain (1:1,000; Millipore), anti–β-actin (1:10,000; Sigma-Aldrich), and anti–syntaxin 4 (1:5,000, Synaptic Systems GmbH) antibodies. Primary antibodies were detected using HRP-labeled secondary antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) and ECL chemiluminescence (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Isolation of the membrane fraction was performed by membrane flotation on sucrose gradients as described by Haghnia et al. (2007). Similar amounts of protein from each fraction were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting.

Time-lapse video microscopy and image analysis

Time-lapse microscopy was performed at 37°C using a Focht Live-Cell Chamber System (Bioptechs) and a TE 200 microscope equipped with a PlanFluor ELWD 60× NA 0.70 objective and a CoolSNAP HQ digital camera controlled by MetaMorph software. Keratinocytes were grown on coverslips coated with collagen-I, and lysosomes were stained with 100 nM of the fluorescence dye LysoTracker red DND-99 (Invitrogen) for 10 min. For time-lapse video analysis, the images of lysosomes were captured every 5 s for 5 min (Cordonnier et al., 2001). The lysosome movement was analyzed using image analysis software (Imaris; Bitplane). The total length of lysosome movement was defined as the sum of its run lengths from the start position to the end position regardless of direction. For latrunculin A experiments, cells were treated with 1 μM latrunculin A or vehicle (DMSO) for 2 h at 37°C, and lysosome movement was analyzed as described above. For low-calcium experiments, cells were washed twice with PBS, cultured in low-calcium epithelial media overnight (>16 h), and analyzed in low-calcium media.

Online supplemental material

Fig. S1 shows that binding of α–E-catenin to β-catenin and dynamitin is mutually exclusive. Fig. S2 shows that α–E-catenin does not interfere with the assembly of dynactin–dynein complexes and dynactin–dynein interaction with vesicles. Fig. S3 shows the generation and analysis of keratinocytes expressing exogenous full-length and truncated (missing the actin-BD) α–E-catenin proteins. Videos 1 and 2 show lysosome movement in wild-type and α–E-catenin−/− keratinocytes, respectively. Videos 3 and 4 show lysosome movement in α–E-catenin−/− keratinocytes expressing the HBT tag and HBT-α–E-catenin, respectively. Videos 5 and 6 show lysosome movement in wild-type and α–E-catenin−/− keratinocytes, respectively, cultured in low-calcium media. Videos 7 and 8 show lysosome movement in latrunculin A–treated wild-type and α–E-catenin−/− keratinocytes, respectively. Video 9 shows lysosome movement in α–E-catenin−/− keratinocytes expressing HBT-α–E-catenin VH1–2. Online supplemental material is available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200805041/DC1.

Acknowledgments

We thank all members of the Vasioukhin laboratory for suggestions, D. Baltimore for the gift of the FUW system, G. Nolan for the gift of the Phoenix system, and P. Kaiser, M. Duñach, W. Weis, and the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank for the gift of plasmids and antibodies. We also thank J. Maycock and M. Null for help with the yeast two-hybrid screen and J. Vazquez and D. McDonald for help with Imaris software.

This work was supported by National Cancer Institute grant CA098161 to V. Vasioukhin and National Institute of General Medical Sciences grant GM-52111 to V.I. Gelfand.

Abbreviations used in this paper: AD, activating domain; AJ, adherens junction; BD, binding domain; E-cadherin, epithelial cadherin; E-catenin, epithelial catenin; F-actin, filamentous actin; HBT, histidine-biotin tag; HEK, human embryonic kidney; IP, immunoprecipitation; KD, knockdown; shRNA, short hairpin RNA.

References

- Aberle, H., S. Butz, J. Stappert, H. Weissig, R. Kemler, and H. Hoschuetzky. 1994. Assembly of the cadherin-catenin complex in vitro with recombinant proteins. J. Cell Sci. 107:3655–3663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Askham, J.M., K.T. Vaughan, H.V. Goodson, and E.E. Morrison. 2002. Evidence that an interaction between EB1 and p150(Glued) is required for the formation and maintenance of a radial microtubule array anchored at the centrosome. Mol. Biol. Cell. 13:3627–3645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin, J.M., and W.J. Nelson. 2008. Bench to bedside and back again: molecular mechanisms of alpha-catenin function and roles in tumorigenesis. Semin. Cancer Biol. 18:53–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berrueta, L., J.S. Tirnauer, S.C. Schuyler, D. Pellman, and B.E. Bierer. 1999. The APC-associated protein EB1 associates with components of the dynactin complex and cytoplasmic dynein intermediate chain. Curr. Biol. 9:425–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullions, L.C., D.A. Notterman, L.S. Chung, and A.J. Levine. 1997. Expression of wild-type alpha-catenin protein in cells with a mutant alpha-catenin gene restores both growth regulation and tumor suppressor activities. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17:4501–4508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X., S. Kojima, G.G. Borisy, and K.J. Green. 2003. p120 catenin associates with kinesin and facilitates the transport of cadherin–catenin complexes to intercellular junctions. J. Cell Biol. 163:547–557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordonnier, M.N., D. Dauzonne, D. Louvard, and E. Coudrier. 2001. Actin filaments and myosin I alpha cooperate with microtubules for the movement of lysosomes. Mol. Biol. Cell. 12:4013–4029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deacon, S.W., A.S. Serpinskaya, P.S. Vaughan, M. Lopez Fanarraga, I. Vernos, K.T. Vaughan, and V.I. Gelfand. 2003. Dynactin is required for bidirectional organelle transport. J. Cell Biol. 160:297–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haghnia, M., V. Cavalli, S.B. Shah, K. Schimmelpfeng, R. Brusch, G. Yang, C. Herrera, A. Pilling, and L.S. Goldstein. 2007. Dynactin is required for coordinated bidirectional motility, but not for dynein membrane attachment. Mol. Biol. Cell. 18:2081–2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirano, S., N. Kimoto, Y. Shimoyama, S. Hirohashi, and M. Takeichi. 1992. Identification of a neural alpha-catenin as a key regulator of cadherin function and multicellular organization. Cell. 70:293–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobielak, A., and E. Fuchs. 2004. Alpha-catenin: at the junction of intercellular adhesion and actin dynamics. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 5:614–625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lien, W.H., O. Klezovitch, T.E. Fernandez, J. Delrow, and V. Vasioukhin. 2006. alphaE-catenin controls cerebral cortical size by regulating the hedgehog signaling pathway. Science. 311:1609–1612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ligon, L.A., S. Karki, M. Tokito, and E.L. Holzbaur. 2001. Dynein binds to beta-catenin and may tether microtubules at adherens junctions. Nat. Cell Biol. 3:913–917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lois, C., E.J. Hong, S. Pease, E.J. Brown, and D. Baltimore. 2002. Germline transmission and tissue-specific expression of transgenes delivered by lentiviral vectors. Science. 295:868–872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quintyne, N.J., S.R. Gill, D.M. Eckley, C.L. Crego, D.A. Compton, and T.A. Schroer. 1999. Dynactin is required for microtubule anchoring at centrosomes. J. Cell Biol. 147:321–334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roura, S., S. Miravet, J. Piedra, A. Garcia de Herreros, and M. Dunach. 1999. Regulation of E-cadherin/Catenin association by tyrosine phosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem. 274:36734–36740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroer, T.A. 2004. Dynactin. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 20:759–779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shtutman, M., A. Chausovsky, M. Prager-Khoutorsky, N. Schiefermeier, S. Boguslavsky, Z. Kam, E. Fuchs, B. Geiger, G.G. Borisy, and A.D. Bershadsky. 2008. Signaling function of alpha-catenin in microtubule regulation. Cell Cycle. 7:2377–2383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swift, S., J. Lorens, P. Achacoso, and G.P. Nolan. 2001. Rapid production of retroviruses for efficient gene delivery to mammalian cells using 293T cell-based systems. Curr. Protoc. Immunol. Chapter 10:Unit 10.17C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tagwerker, C., K. Flick, M. Cui, C. Guerrero, Y. Dou, B. Auer, P. Baldi, L. Huang, and P. Kaiser. 2006. A tandem affinity tag for two-step purification under fully denaturing conditions: application in ubiquitin profiling and protein complex identification combined with in vivocross-linking. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 5:737–748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeichi, M., and S. Nakagawa. 1998. Cadherin-dependent cell–cell adhesion. In Current Protocols in Cell Biology. J.S. Bonifacino et al., editors. John Wiley & Sons Inc., New York. 9.3.1–9.3.15. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Torres, M., A. Stoykova, O. Huber, K. Chowdhury, P. Bonaldo, A. Mansouri, S. Butz, R. Kemler, and P. Gruss. 1997. An alpha-E-catenin gene trap mutation defines its function in preimplantation development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 94:901–906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasioukhin, V., C. Bauer, M. Yin, and E. Fuchs. 2000. Directed actin polymerization is the driving force for epithelial cell-cell adhesion. Cell. 100:209–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasioukhin, V., C. Bauer, L. Degenstein, B. Wise, and E. Fuchs. 2001. Hyperproliferation and defects in epithelial polarity upon conditional ablation of alpha-catenin in skin. Cell. 104:605–617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughan, K.T., and R.B. Vallee. 1995. Cytoplasmic dynein binds dynactin through a direct interaction between the intermediate chains and p150Glued. J. Cell Biol. 131:1507–1516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]