Abstract

Background

Intestinal transport exhibits distinct diurnal rhythmicity. Understanding the mechanisms behind this may reveal new therapeutic strategies to modulate intestinal function in disease states such as diabetes and obesity, as well as short bowel syndrome. Although diurnal rhythms have been amply documented for several intestinal transporters, the complexity of transepithelial transport has precluded definitive attribution of rhythmicity in glucose uptake to a single transporter. To address this gap, we assessed temporal changes in glucose transport mediated by the Na+/glucose co-transporter SGLT1.

Methods

SGLT1 expression was assessed at 4 times during the day: ZT3, ZT9, ZT15 and ZT21 (ZT, Zeitgeber time; lights-on at ZT0; n=8/ time). SGLT1 activity, defined as glucose uptake sensitive to the specific SGLT1 inhibitor phloridzin, was measured in everted intestinal sleeves. Changes in Sglt1 expression were assessed by real-time PCR and immunoblotting.

Results

Glucose uptake was significantly higher at ZT15 in jejunum (p<0.05 vs. ZT3). Phloridzin significantly reduced glucose uptake and completely abolished its rhythmicity. Sglt1 mRNA levels were significantly higher at ZT9 and ZT15 in jejunum and ileum respectively (p<0.05 vs. ZT3), while SGLT1 protein levels were significantly higher at ZT15 in jejunum (p<0.05 vs. ZT3).

Conclusions

Our results definitively link diurnal changes in intestinal glucose uptake capacity to changes in both SGLT1 mRNA and protein. These findings suggest that modulation of transporter expression would enhance intestinal function and provides an impetus to elucidate the mechanisms underlying diurnal rhythmicity in transcription. Modulation of intestinal function would benefit the management of malnutrition as well as diabetes and obesity.

Keywords: Diabetes, obesity, everted sleeves, intestinal adaptation

Introduction

Intestinal transporter expression and absorptive function have long been known to exhibit diurnal rhythmicity. This rhythmicity is adaptive to nutrient availability and is cued to the feeding rhythm rather than to the light cycle, distinguishing them from the endogenous circadian rhythms generated by the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) 1-3. Of particular interest, diurnal intestinal rhythms anticipate luminal nutrient availability, as induction occurs before the onset of feeding. In this context, we demonstrated that the daily induction of the intestinal Na+-glucose co-transporter (SGLT1) anticipates the onset of feeding at the transcriptional level. This phenomenon was observed in both rats (a nocturnal species) as well as non-human primates, suggesting applicability to humans 4. These rhythms have also been found to persist in the absence of luminal nutrients, and for up to 4 days of food deprivation in rodents3, 5. This timing presumably allows maximal expression of transporters to coincide with nutrient delivery, thereby optimizing energy utilization for protein synthesis 6-8. Although diurnal rhythmicity in the absorption of glucose and other substrates has been previously documented, functional changes have not been conclusively linked to altered expression and/or activity of specific transporters. A demonstration that SGLT1 is specifically responsible for the glucose absorptive rhythm would establish SGLT1 rhythmicity as a novel and physiologically important model to study this transporter, and would emphasize the importance of deciphering the underlying molecular mechanisms regulating these adaptive diurnal changes.

We undertook this study to discern the specific involvement of SGLT1 in the diurnal rhythmicity of intestinal glucose uptake, and investigate glucose absorptive capacity at the enterocyte level. To achieve this goal, we used the everted sleeve technique because it permits measurement of the temporal changes in glucose uptake activity in intact, minimally-disrupted intestinal tissues. Moreover, SGLT1 activity can be isolated from the overall glucose flux by (i) limiting the uptake measurement to the apical transport step, (ii) relying on the sensitivity of SGLT1 to the specific inhibitor phloridzin, and (iii) using its actual substrate d-glucose, rather than a non-metabolized substrate as used in previous experiments 3. This definitive evidence for a functional diurnal rhythmicity in the activity of a single gene product (SGLT1) establishes SGLT1 regulation as an explicit model to characterize the mechanisms of intestinal diurnal rhythmicity. Better understanding of this regulatory pathway may reveal strategies to modulate SGLT1 expression in therapeutic management of diabetes, obesity, and short bowel syndrome.

Materials and Methods

Animal studies

The study protocols were approved by the Harvard Medical Area Standing Committee on Animals.

Thirty-two male Sprague-Dawley rats were purchased from Harlan (Indianapolis, IN) and acclimatized to a 12-hour photoperiod for 5 days with ad libitum access to food and water. Rats were then killed at 6-hourly time intervals beginning at ZT3 (where ZT is Zeitgeber Time, and ZT 0 is lights on (7am), n=8 per time point).

Tissue harvest

Rats were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of sodium pentobarbital (50mg/kg, Ovation Pharmaceuticals, Deerfield, IL). Midline laparotomy was performed, and intestine was harvested from 2cm distal to the Ligament of Treitz to the ileocecal junction and rinsed with ice cold saline to remove any luminal contents. The first 15cm of intestine was divided into 1.5cm segments and placed in ice-cold Ringer's solution to be used for the everted sleeve technique. The subsequent 8cm of intestine was divided along the antimesenteric border and the mucosa scraped off the underlying muscle, snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and subsequently stored at -80°C for RNA extraction. The next 8cm of intestine was divided along the antimesenteric border and the mucosa scraped and placed into Triton lysis buffer (Boston Bioproducts, Ashland, MA) containing 1% protease inhibitor (Sigma, St Louis, MI) for protein extraction. Ileal tissue was obtained from an 8cm segment of intestine proximal to the ileocecal valve for RNA extraction using the methods described above.

RNA extraction, reverse transcription and real-time PCR

Total RNA was extracted from the mucosal samples using the MiRvaNA kit (Ambion; Austin, TX). Reverse transcription was performed with oligoDT priming using the Superscript III kit (Invitrogen; Carlsbad, CA). All reactions were performed simultaneously to maximize consistency.

Real-time PCR was carried out on a Geneamp 5700 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) using the SYBR Green kit mastermix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). All samples underwent real-time PCR simultaneously to minimize errors introduced by variations in the efficiency of the reaction. Reaction mixtures contained 2 μl experimental cDNA sample and 12.5 pmol each of forward and reverse primers in a total volume of 12.5 μl. Primer sequences used were:

SGLT1 Forward 5′-CCAAGCCCATCCCAGACGTACACC-3′;

SGLT1 Reverse 5′-CTTCCTTAGTCATCTTCGGTCCTT-3′;

GAPDH Forward 5′- GATGGTGAAGGTCGGTGTGAACGG-3′;

GAPDH Reverse 5′- AGACTCCACGACATACTCAGCACC-3′

Real-time PCR was carried out for 2 minutes at 50°C, 10 minutes at 95°C, then 40 cycles of 15 seconds at 95°C and 1 minute at 60°C. Fluorescence was measured at the end of each 60°C step. Sglt1 mRNA level was expressed as a ratio to Gapdh, a stably-expressed housekeeping gene that does not exhibit diurnal variation, used as an internal control. Melting curve analysis was performed to confirm that all samples were free of multiple amplicons, nonspecific products or contaminants.

Immunoblot analysis

Protein from jejunal and ileal segments was extracted by sonication and homogenization followed by centrifugation at 11,000g for 15 minutes to remove debris. The protein concentration was measured in the supernatant using the bicinchoninic acid method (Sigma, St Louis, MI) and standardized to bovine serum albumin.

Extracts (100ug protein) were resolved on 10% Bis-Tris gels and transferred to PVDF membranes. Membranes were blocked with casein and incubated overnight with 1:4000 dilution of anti-SGLT1 antibody raised in rabbit (Chemicon International, Temecula, California). Secondary antibody was goat anti-rabbit IgG-HRP (Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA). Visualization was performed with ECL Western Blotting Detection Reagents (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ) and exposure to radiographic film (Eastman Kodak, Rochester, NY). Membranes were stripped and reprobed with a 1:1000 dilution of anti-actin antibody raised in mouse (Labvision, Fremont, CA) and horse anti-mouse IgG-HRP secondary antibody (Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA) to normalize for protein loading.

The developed film was scanned (ArcPhoto Software, Fremont, Ca) and densitometry readings were obtained for each band using ImageProPlus software (Mediacybernetics, Bethesda, MD). Measurements for SGLT1 were expressed as a ratio to the corresponding actin band for each sample.

Everted sleeve technique

Segments of jejunum measuring 1.5cm were everted onto custom-made glass rods, mucosal surface facing outward, and secured with silk ligatures over grooves 1cm apart. The sleeves were equilibrated for 30 minutes in ice-cold oxygenated Ringer's solution (solution composition (in mM) was 128 NaC1, 4.7 KC1, 2.5 CaC12, 1.2 KH2PO4, 1.2 MgSO4, 20 NaHCO3; pH 7.3-7.4, 95%O2/5%CO2). Glucose uptake measurements were performed according to a published method 9. The first 3 sleeves from each animal were pre-incubated for 4 minutes in oxygenated Ringer's solution with 6mM DMSO (Sigma, St Louis, MO), then incubated for 2 minutes in oxygenated Ringer's solution also containing 5.6mCi/ml [1-3H]-l-glucose (Moravek, Brea, CA) and 0.9mCi/ml [U-14C]-d-glucose (Perkin-Elmer, Waltham, MA) and 1M non-radioactive D-glucose, then rinsed for 20 seconds in ice cold Ringer's solution. The next 3 sleeves from each animal were pre-incubated for 4 minutes in Ringer's solution with 0.1mM phloridzin warmed to 37°C, then incubated for 2 minutes in Ringer's solution containing the same radiolabeled sugars as well as 0.1mM phloridzin then rinsed for 20 seconds in ice cold Ringers' solution. The 1cm sleeve segments were from each rod, weighed, and dissolved in 500ul Soluene 350 (Perkin-Elmer) in scintillation vials. Scintillation counting was performed in a scintillation chamber (Beckman-Coulter, Fullerton, CA) with Hyonic Fluor (Perkin-Elmer). Calculations were performed as described previously 9, according to the formula:

(P-RM)/htm = J,

where P is the DPM of the 14C isotope, R is the ratio of the DPM of 14C to 3H isotope in the incubation solution, M is the DPM of the 3H isotope in the tissue, h is the DPM of the 14C in the incubation solution, t is the time for incubation (min) and m is the length(cm).

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as means ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Probability of p < 0.05 was taken as significant. p values were estimated using ANOVA with post-hoc multiple group comparisons and Students t-test for comparisons between 2 groups. Computations were performed using a commercially available statistical package (Statistica, version 4.3, StatSoft, Tulsa, OK).

Results

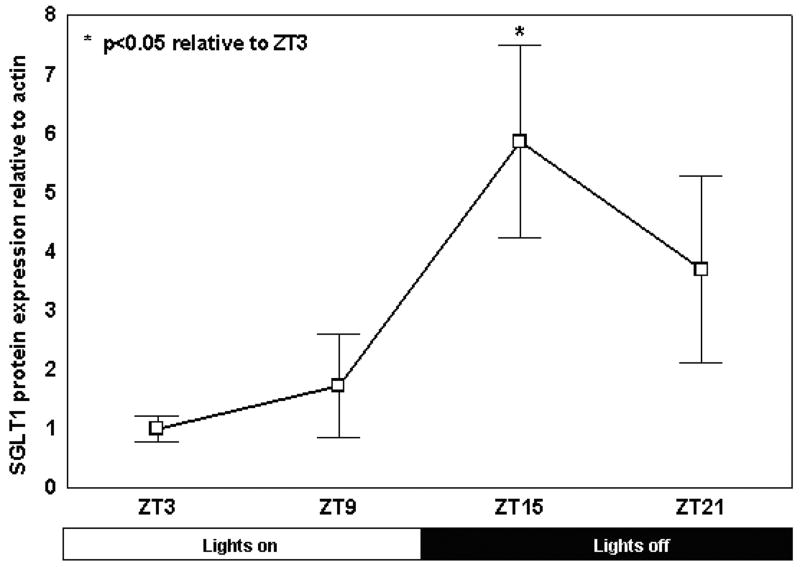

a) Diurnal variation in SGLT1-mediated glucose uptake

Uptake of 14C-labelled glucose followed a diurnal rhythm, with a peak occurring at ZT15, the time of maximal SGLT1 protein expression. Glucose uptake at ZT15 was 1.9-fold higher than at ZT3 (p<0.05 compared to levels at ZT3, Table 1 and Fig. 1). Pretreatment with specific SGLT1 inhibitor phloridzin abolished the previously noted rhythmicity in glucose uptake and significantly reduced levels of uptake at all timepoints compared to incubation without phloridzin (p<0.005, Table 1, Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Diurnal variation in radiolabeled glucose uptake by the everted sleeve method. Values are expressed as means ± SE. 14C-labelled glucose uptake was significantly higher at ZT15 compared with ZT3 (*p < 0.05 uptake in the absence of phloridzin at ZT15 vs. ZT3, n=8). The addition of phloridzin, a specific inhibitor of SGLT1, abolished this difference in uptake and significantly reduced 14C -labeled glucose uptake across all timepoints compared to incubation without phloridzin (†p<0.005, n=8).

| Timepoint | Glucose uptake in absence of phloridzin (nmol/mg) | Glucose uptake in presence of phloridzin (nmol/mg) |

|---|---|---|

| ZT3 | 1343.2 ± 245.5 | 185.7 ± 99.9† |

| ZT9 | 1952.7 ± 339.2 | 209.3 ± 166.7† |

| ZT15 | 2569.1 ± 269.5* | 264.6 ± 85.0† |

| ZT21 | 2216.0 ± 402.6 | 234.8 ± 99.4† |

p < 0.05 uptake in the absence of phloridzin at ZT15 vs. ZT3,

p<0.005 uptake in the absence of phloridzin vs uptake in the presence of phloridzin at the same timepoint

Fig. 1. Diurnal variation in radiolabeled glucose uptake by the everted sleeve method.

14C-labelled glucose uptake was significantly higher at ZT15 compared with ZT3 (*p < 0.05 uptake in the absence of phloridzin at ZT15 vs. ZT3, n=8). The addition of phloridzin, a specific inhibitor of SGLT1, abolished this difference in uptake and significantly reduced 14C-labelled glucose uptake across all timepoints compared to incubation without phloridzin (†p<0.005, n=8). This shows that the observed rhythmicity in sugar absorption was caused by alterations in the activity of SGLT1. There is no significant difference between the 4 time points for post-phloridzin glucose uptake.

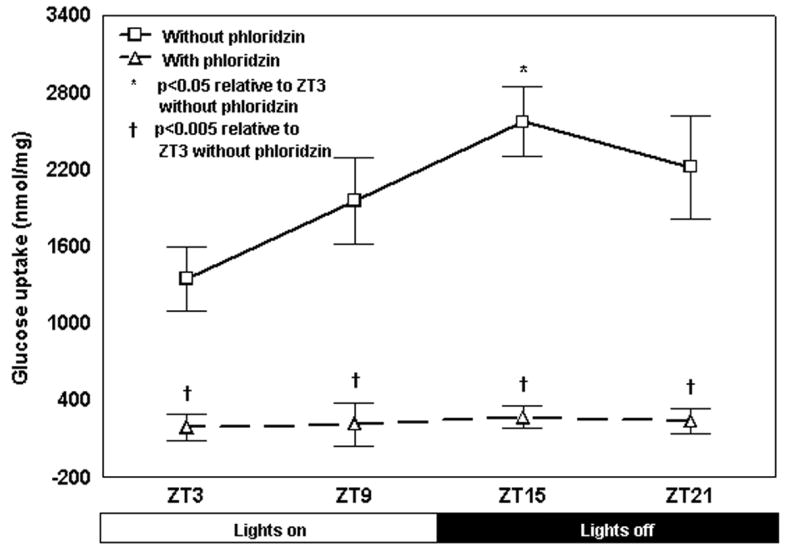

b) Diurnal variation in Sglt1 mRNA expression in jejunum vs ileum

Jejunal mRNA expression of Sglt1 exhibited diurnal rhythmicity, with levels peaking at ZT 9, corresponding to 4pm (p<0.01 compared to levels at ZT3 and ZT21, Fig. 2). Sglt1 mRNA in the jejunum exhibited a 4.6-fold peak-trough difference (ZT9 compared to ZT21). In contrast, in the terminal ileum, diurnal rhythmicity in mRNA expression was blunted, with a 3.9-fold peak-trough difference. Ileal Sglt1 mRNA expression was significantly higher at ZT9 and ZT15 than ZT3 or ZT21 (p<0.01 relative to ZT3 and ZT21, Fig. 2). The peak in mRNA expression in terminal ileum occurred at ZT15, six hours later than the peak noted in the jejunum.

Fig. 2. Diurnal rhythmicity of Sglt1 mRNA expression in jejunal and ileal mucosa.

mRNA levels of Sglt1 were significantly higher at ZT9 in jejunum compared to ZT3 and ZT21. mRNA levels in ileum demonstrated a blunted but more sustained elevation at ZT9 and ZT15, both significantly higher than ZT3 and ZT21( *p < 0.01 compared with ZT3 and ZT21, n=6).

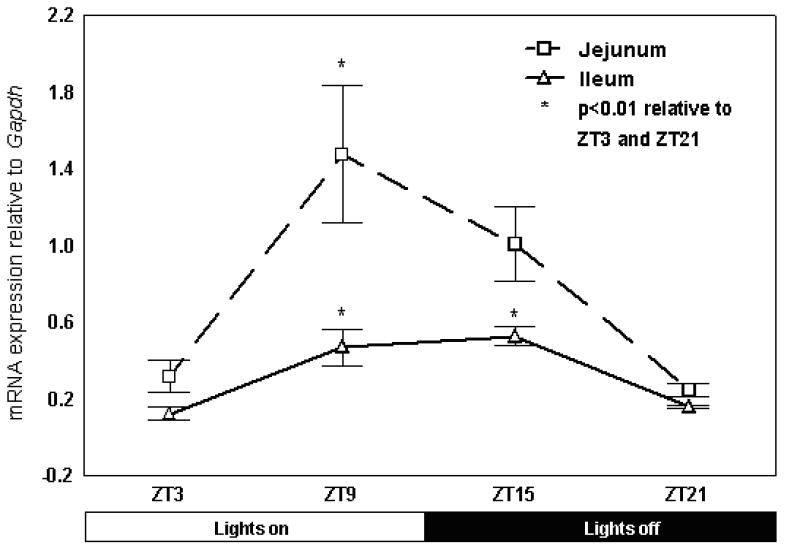

c) Diurnal variation in SGLT1 protein expression in jejunum

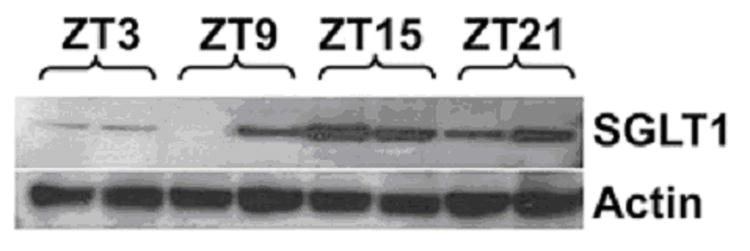

Protein levels in the jejunum also exhibited a diurnal rhythmicity, with a 5.9-fold peak-trough difference. The peak in SGLT1 protein expression however occurred at ZT15, a six hour delay compared to the mRNA peak (p<0.05 compared to levels at ZT3, Fig. 3a and b).

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3a: Diurnal variation in SGLT1 protein expression as shown by Western blotting. Intensity of each band as measured on densitometry was indexed to the first band on each gel and normalized to the housekeeping protein actin as an internal control. A representative blot is shown below.

Fig. 3b: Diurnal variation in jejunal SGLT1 protein expression. SGLT1 levels were significantly higher at ZT15 compared to ZT3 (*p < 0.05 compared with ZT3, n=6).

Discussion

Striking rhythmicity in intestinal transporter expression occurs on a diurnal basis and functional diurnal changes in intestinal absorption of glucose and other nutrients have been amply documented. Previous studies have shown regulation at the transcriptional level 4. The most significant finding of the present study is our demonstration that these transcriptional changes culminate in a diurnal rhythmicity in the activity of a single gene product, SGLT1. Furthermore, the peak in SGLT1 activity corresponded with the peak in the level of SGLT1 protein. Lastly, we found that temporal changes in Sglt1 mRNA levels persisted in the ileum with a lower amplitude and a later peak than in the jejunum.

To date, only a few studies have definitively demonstrated that functional changes accompany diurnal rhythms in intestinal gene expression. Our previous electrophysiological studies confirmed diurnal rhythmicity in transepithelial hexose transport capacity, a relevant physiological parameter for assessing intestinal function 3. However, the complex nature of transepithelial transport precluded drawing a definitive conclusion regarding the specific involvement of SGLT1. To isolate apical SGLT1 activity specifically, we used the everted sleeve technique to measure cellular glucose uptake, a more precise measure of SGLT1 activity than transepithelial glucose absorption. As expected we demonstrated a diurnal rhythm in intestinal glucose uptake, which was inhibited in the presence of phloridzin, a specific inhibitor of SGLT1-mediated glucose uptake at the dose used. Glucose uptake in the presence of phloridzin was significantly decreased and the diurnal rhythmicity abolished. Thus, SGLT1 is responsible for the diurnal rhythm in intestinal glucose uptake. We note that the peak in uptake activity we observed with the sleeves occurred later than that obtained with electrophysiological measurements using Ussing chambers, which revealed maximal uptake at ZT9 3. This difference is likely due to isolation of SGLT1 activity vs. the composite process captured by the electrophysiological measurements. Our observations are in agreement with the study by Pan et al demonstrating a peak in α-methylglucoside uptake during the dark phase and a nadir at mid-light phase 10. Using the everted sleeve technique, we also demonstrated maximal expression of SGLT1 protein at the time of peak SGLT1 activity, lending further support that the change in function is due, at least in part, to a change in Vmax.

The key role played by SGLT1 in the diurnal rhythm of glucose uptake is unsurprising, but SGLT1 may also play a more general role in the diurnal rhythms in intestinal absorption. In conjunction with the Na+/K+-ATPase, SGLT1 contributes significantly to fluid absorption 11-13. Glucose/galactose movement in conjunction with basolateral Na+ extraction creates an osmotic gradient that drives water (in excess of 250 H2O/hexose) through the epithelium. This flux further creates a “solvent drag” that induces absorption of additional solutes. Fructose uptake via apical GLUT5 not only occurs by this mechanism 14 but is enhanced when fructose is released from sucrose along with glucose rather than delivered as separate monosaccharides 15. Other Na+-coupled transporters, such as the renal Na+-dicarboxylate co-transporter, also enhance fluid absorption 16. These considerations lead us to suggest a model in which Na+-coupled transporters catalyze specific nutrient absorption rhythms as well as amplify overall intestinal absorption via solvent drag created by the induced H2O flux.

Moderation of the SGLT1 rhythm in the ileum, as evidenced by the reduced amplitude in Sglt1 mRNA levels, is likely due to greater continuity in distal nutrient delivery. Nevertheless, a rhythm remained readily detectable. The temporal difference in peak mRNA expression from the jejunum (ZT15 vs. ZT9 in this study) is consistent with intestinal transit times.

Other intestinal genes have also been shown to demonstrate diurnal variation in expression, including the peptide transporter PEPT1 and sucrase-isomaltase 2, 10. Furthermore, diurnal rhythms have also been noted in lipid absorption, with a peak in uptake of triglycerides and cholesterol during the nocturnal feeding period in mice 17. Together this represents a dynamic alteration in intestinal function designed to optimize absorption in anticipation of nutrient delivery. Neural, hormonal and nutrient factors have all been postulated to play a role in the regulation of diurnal rhythms 2, 18, 19, with recent interest particularly in the role of the vagus nerve. We have previously shown persistent rhythmicity in SGLT1 mRNA expression following total vagotomy, corresponding with the study by Houghton et al, suggesting that transcriptional regulation of the diurnal rhythmicity of SGLT1 is outside vagal control 18, 19.

Many hormones are known to exhibit diurnal variation, including the hormones glucose-dependent insulinotrophic peptide (GIP), ghrelin and leptin 20. These hormones have been shown to respond to feeding, and in rats, exhibit a reversal of the pattern of rhythmicity on restricting the period of nutrient availability, suggesting a role for luminal nutrients in entrainment of these rhythms. Plasma leptin levels in particular are noted to exhibit a peak in expression during the dark (feeding) period, and a trough in the light (resting) period. A recent study by Inigo et al showed that luminal leptin inhibits SGLT1-mediated glucose uptake in vivo, suggesting that leptin may prove a worthy candidate for further study on the hormonal contribution to diurnal variation of SGLT1-mediated glucose uptake 21, 22.

We have shown in this study diurnal rhythmicity in jejunal mRNA expression of Sglt1 and a persistence of this rhythmicity with a phase delay in the ileum. In addition we have shown that this rhythmicity in the SGLT1 mRNA expression results soon afterwards in a peak in SGLT1 protein and function. Our study improves the understanding behind the molecular mechanisms behind diurnal variation in intestinal function and paves the way for further efforts in identifying therapeutic modalities to optimize intestinal absorption.

Acknowledgments

The authors would also like to acknowledge the excellent technical assistance of Amarsanaa Jazag and Kaori Ito.

Grants: This study was funded by the NIH grant 5 R01 DK047326 (SWA), March of Dimes Grant#1-FY99-221 (DBR), and the Harvard Clinical Nutrition Research Center grant (AT) P30-DK040561.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Nishida T, Saito M, Suda M. Parallel between circadian rhythms of intestinal disaccharidases and foot intake of rats under constant lighting conditions. Gastroenterology. 1978;74:224–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stevenson NR, Ferrigni F, Parnicky K, Day S, Fierstein JS. Effect of changes in feeding schedule on the diurnal rhythms and daily activity levels of intestinal brush border enzymes and transport systems. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1975;406:131–45. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(75)90048-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tavakkolizadeh A, Berger UV, Shen KR, Levitsky LL, Zinner MJ, Hediger MA, Ashley SW, Whang EE, Rhoads DB. Diurnal rhythmicity in intestinal SGLT-1 function, V(max), and mRNA expression topography. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2001;280:G209–15. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.2001.280.2.G209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rhoads DB, Rosenbaum DH, Unsal H, Isselbacher KJ, Levitsky LL. Circadian periodicity of intestinal Na+/glucose cotransporter 1 mRNA levels is transcriptionally regulated. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:9510–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.16.9510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pan X, Terada T, Okuda M, Inui K. The diurnal rhythm of the intestinal transporters SGLT1 and PEPT1 is regulated by the feeding conditions in rats. J Nutr. 2004;134:2211–5. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.9.2211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fisher RB, Gardner ML. A diurnal rhythm in the absorption of glucose and water by isolated rat small intestine. J Physiol. 1976;254:821–5. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1976.sp011262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Furuya S, Takahashi S. Absorption of L-histidine and glucose from the jejunum segment of the pig and its diurnal fluctuation. Br J Nutr. 1975;34:267–77. doi: 10.1017/s0007114575000311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hara E, Saito M. Diurnal change in digestion and absorption of sucrose in vivo in rats. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol (Tokyo) 1989;35:667–71. doi: 10.3177/jnsv.35.667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karasov WH, Diamond JM. A simple method for measuring intestinal solute uptake in vitro. J Comp Physiol. 1983;152:105–116. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pan X, Terada T, Irie M, Saito H, Inui K. Diurnal rhythm of H+-peptide cotransporter in rat small intestine. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2002;283:G57–64. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00545.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zeuthen T, Meinild AK, Loo DD, Wright EM, Klaerke DA. Isotonic transport by the Na+-glucose cotransporter SGLT1 from humans and rabbit. J Physiol. 2001;531:631–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0631h.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duquette PP, Bissonnette P, Lapointe JY. Local osmotic gradients drive the water flux associated with Na(+)/glucose cotransport. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:3796–801. doi: 10.1073/pnas.071245198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zeuthen T, Meinild AK, Klaerke DA, Loo DD, Wright EM, Belhage B, Litman T. Water transport by the Na+/glucose cotransporter under isotonic conditions. Biol Cell. 1997;89:307–12. doi: 10.1016/s0248-4900(97)83383-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ferraris RP. Dietary and developmental regulation of intestinal sugar transport. Biochem J. 2001;360:265–76. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3600265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Riby JE, Fujisawa T, Kretchmer N. Fructose absorption. Am J Clin Nutr. 1993;58:748S–753S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/58.5.748S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meinild AK, Loo DD, Pajor AM, Zeuthen T, Wright EM. Water transport by the renal Na(+)-dicarboxylate cotransporter. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2000;278:F777–83. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.2000.278.5.F777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pan X, Hussain MM. Diurnal regulation of microsomal triglyceride transfer protein and plasma lipid levels. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:24707–19. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701305200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Houghton SG, Zarroug AE, Duenes JA, Fernandez-Zapico ME, Sarr MG. The diurnal periodicity of hexose transporter mRNA and protein levels in the rat jejunum: role of vagal innervation. Surgery. 2006;139:542–9. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2005.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tavakkolizadeh A, Ramsanahie A, Levitsky LL, Zinner MJ, Whang EE, Ashley SW, Rhoads DB. Differential role of vagus nerve in maintaining diurnal gene expression rhythms in the proximal small intestine. J Surg Res. 2005;129:73–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2005.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bodosi B, Gardi J, Hajdu I, Szentirmai E, Obal F, Jr, Krueger JM. Rhythms of ghrelin, leptin, and sleep in rats: effects of the normal diurnal cycle, restricted feeding, and sleep deprivation. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2004;287:R1071–9. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00294.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Inigo C, Patel N, Kellett GL, Barber A, Lostao MP. Luminal leptin inhibits intestinal sugar absorption in vivo. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2007;190:303–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2007.01707.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ducroc R, Guilmeau S, Akasbi K, Devaud H, Buyse M, Bado A. Luminal leptin induces rapid inhibition of active intestinal absorption of glucose mediated by sodium-glucose cotransporter 1. Diabetes. 2005;54:348–54. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.2.348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]