Abstract

Genetic analysis of parasitic nematodes has been a neglected area of research and the basic genetics of this important group of pathogens are poorly understood. Haemonchus contortus is one of the most economically significant livestock parasites worldwide and is a key experimental model for the strongylid nematode group that includes many important human and animal pathogens. We have undertaken a study of the genetics and the mode of mating of this parasite using microsatellite markers. Inheritance studies with autosomal markers demonstrated obligate dioecious sexual reproduction and polyandrous mating that are reported here for the first time in a parasitic helminth and provide the parasite with a mechanism of increasing genetic diversity. The karyotype of the H. contortus, MHco3(ISE) isolate was determined as 2n = 11 or 12. We have developed a panel of microsatellite markers that are tightly linked on the X chromosome and have used them to determine the sex chromosomal karyotype as XO male and XX female. Haplotype analysis using the X-chromosomal markers also demonstrated polyandry, independent of the autosomal marker analysis, and enabled a more direct estimate of the number of male parental genotypes contributing to each brood. This work provides a basis for future forward genetic analysis on H. contortus and related parasitic nematodes.

GENETIC studies on parasitic nematodes have been predominantly confined to a limited number of population genetic studies, although there has been recent interest in using these approaches to investigate parasite epidemiology and the evolution of drug resistance (Blouin et al. 1995; Anderson 2001; Nejsum et al. 2005; Troell et al. 2006; Criscione et al. 2007; Gilleard and Beech 2007). In contrast to the progress made in mapping genes associated with traits such as drug resistance and virulence in parasitic protozoa, forward genetic approaches have yet to be applied to parasitic helminths (Tait et al. 2002; Su et al. 2007). Haemonchus contortus is one of the most economically significant livestock parasites worldwide and is an important experimental model for the strongylid nematode group that includes many important human and animal pathogens (Knox et al. 2003; Gilleard 2006). It is one of the more amenable parasitic nematodes to genetic analysis, having high levels of genetic polymorphism both within and between isolates and being one of the very few parasitic nematode species in which genetic crosses between isolates have been successfully undertaken (Beech et al. 1994; Hoekstra et al. 1997, 1999; Sangster et al. 1998; Le Jambre et al. 1999; Otsen et al. 2000a,b; Troell et al. 2006; Redman et al. 2008). Although genetic crossing is experimentally possible, it has been minimally exploited due to technical challenges associated with setting up paired matings, a lack of information on the basic genetics of the organism, and the limited number of available genetic markers. However, the H. contortus genome project is currently one of the most advanced of the parasitic nematodes with ∼800 Mb of shotgun sequence currently available and with ongoing work on full genome assembly and annotation (http://www.sanger.ac.uk/Projects/H_contortus/). Hence genetic marker development should no longer be a limiting factor and so H. contortus now has the potential to become a powerful experimental system in which to study parasitic nematode genetics and develop forward genetic approaches to study phenomena such as anthelmintic resistance, drug mode-of-action, and host–pathogen interactions (Le Jambre 1977; Le Jambre et al. 1979, 2000; Sangster et al. 1998; Gilleard 2006). Consequently, we are investigating the basic genetics of this organism and developing genetic tools to allow such genetic analysis to become a reality. H. contortus is assumed to be an obligate sexually reproducing dioecious organism on the basis of the presence of morphologically discrete male and female adult worms. There is a single study of karyotype using cytological techniques but there have been no studies on karyotype or mating patterns using genetic markers and analysis (Bremner 1954, 1955). In this article we present genetic analysis of the H. contortus MHco3(ISE) isolate that is currently being used for the genome sequencing project and also of a second genetically divergent isolate MHco4(WRS) (Redman et al. 2008). We have developed a panel of X-linked microsatellite markers and have used them, along with a previously characterized panel of autosomal markers, to investigate the basic genetics, the chromosomal basis of sex determination, and the mode of mating of this nematode parasite. This study provides a framework that is necessary to develop forward genetic strategies and mapping studies on this and other parasitic nematode species.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Isolation of progeny and broods from single adult female worms:

The two H. contortus isolates used in this study were MHco3(ISE) and MHco4(WRS), which were previously genetically characterized using the panel of autosomal markers used in this article (Redman et al. 2008). Experimental infections were performed at the Moredun Institute by oral administration of 5000 L3 larvae into 4- to 12-month-old Greyface cross Suffolk lambs that had been reared and maintained indoors under conditions designed to eliminate the risk of trichostrongylid nematode infection. Individual adult female worms were obtained on autopsy and immediately placed into PBS in separate wells of 24-well plates and were left at 37° overnight to lay eggs. Adult female worms were removed the following day and decapitated, and the head was retained for DNA lysate preparation, taking care to avoid contamination with progeny. After 24 hr, once the progeny had hatched from eggs as L1 larvae, they were removed from the wells and single-worm DNA lysates were prepared.

Preparation of DNA templates:

DNA lysates were made from the female heads and the L1 progeny of these adults, using standard techniques (Redman et al. 2008). One microliter of a 1:30 dilution of a female head lysate or a 1:10 dilution of L1 lysate was used as PCR template. Dilutions of several aliquots of lysate buffer, made in parallel, were included as negative controls for all PCR amplification experiments. All adult female head and progeny lysates from each brood were subjected to two independent, previously published PCR assays to confirm species identity as H. contortus. The first PCR assay amplifies the ITS-2 region and the second amplifies the nontranscribed spacer (NTS) of the rDNA cistron (Wimmer et al. 2004; Redman et al. 2008).

Microsatellite genotyping:

The autosomal markers used in this study (Hcms25, Hcms27, Hcms33, Hcms36, Hcms40, Hc22co3, and Hc8a20) were previously characterized and used to genotype the MHco3(ISE) and MHco4(WRS) isolates (Redman et al. 2008). In addition, a new panel of six microsatellite markers (HcmsX142, HcmsX146, HcmsX151, HcmsX182, HcmsX256, and HcmsX337) was developed as part of this work and shown to be located on the X chromosome as presented in the results section.

PCR amplification of microsatellite loci was performed in 20-μl reactions containing 45 mm Tris HCl (pH 8.8), 11 mm (NH4)2SO4, 4.5 mm MgCl2, 6.7 mm 2-mercaptethanol, 4.4 μm EDTA, 113 μg/ml BSA, 2% Tween, 1 mm each deoxyribonucleotide triphosphates, 0.5 μm of each oligonucleotide primer, and 0.2 unit of Taq polymerase (Promega, Madison, WI). Thermocycling conditions were 94° for 2 min followed by 40 cycles of 90° for 15 sec, 54° for 30 sec, and 72° for 1 min. Accurate sizing of microsatellite PCR products by capillary electrophoresis was performed using an ABI Prism 3100 genetic analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The forward primer of each microsatellite primer pair was 5′-end labeled with FAM, HEX, or NED fluorescent dyes (MWG) and electrophoresed with GeneScan ROX 400 (Applied Biosystems) internal size standard. Individual chromatograms were analyzed using Genemapper Software Version 4.0 (Applied Biosystems).

To estimate the genotyping error rate, one brood of each isolate was randomly chosen for each of the seven autosomal microsatellite markers (i.e., two broods per marker) and repeat genotyped (this represents ∼20% of the full data set). Of a total of 195 repeated genotypes there were only 6 genotypes that changed from the original (allele lost or gained). Of the 372 alleles present in the original 195 genotypes these 6 changes represent a 0.016 genotyping error rate per allele (1.6%) due to allelic dropout and/or the genotyping of false alleles. In addition, all female adult worms were genotyped three times with all the markers with no changes in maternal genotype being observed.

Early embryo mitotic metaphase spreads:

Eggs were harvested from fecal samples and prepared for fixation as previously described (Couthier et al. 2004). Embryos at the 10- to 30-cell stage were mounted on slides and permeabilized by freeze cracking, using standard methodology described for Caenorhabditis elegans (Miller and Shakes 1995). Freeze-cracked embryos were fixed by a 5-min immersion in 95% ethanol followed by a 5-min immersion in a 3:1 mix of methanol:acetone and then air dried. To visualize metaphase chromosomes, embryos were stained with 1 μg/ml 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) and 1 μg/ml phenoxypropanol in M9 buffer (Ellis and Horvitz 1986).

Bioinformatic and data analysis:

A total of 408,911 bp of contiguous H. contortus sequence were derived as the consensus of five fully finished overlapping bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) insert sequences (haemapobac13c1, haemapobac7n11, haembac15g16, haembac18h7, and haembac18g2) originally assembled by BAC fingerprint mapping (K. Mungal, S. Humphray, M. Rajandream, M. Quail, A. Coughlan, J. S. Gilleard and M. Berriman, unpublished data). The contig sequence is available at ftp://ftp.sanger.ac.uk/pub/pathogens/Haemonchus/contortus/genome/X_chromosome_fragment/. The 408,911-bp H. contortus sequence contig was split into 50-kb sections and used to BLAST X search the C. elegans WormPep database (http://www.sanger.ac.uk/cgi-bin/blast/submitblast/c_elegans). A BLAST hit to a C. elegans gene with an E-value of ≤1e−08 where the next best hit had an E-value >0.01 was considered to indicate a likely orthologous gene. The results of this analysis are shown in supplemental Table S2.

The observed and expected heterozygosity, average number of alleles per locus, estimates of FIS, and linkage disequilibrium were calculated using Arelquin version 3.11 (Excoffier and Schneider 2005). Data were defined as “standard” rather than “microsatellite,” as loci did not necessarily adhere to the stepwise mutation model. An unbiased estimate of expected heterozygosity was based on Nei (1978). Exact tests for Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium were performed per locus, using an extension of Fisher's exact probability test based on contingency tables (Raymond and Rousset 1995). For genotypic data with unknown gametic phase, the initial contingency table was constructed from genotypic frequencies and a Markov chain was used to explore all potential states (Markov chain steps, 100,000; dememorization steps, 1000). Pairwise linkage disequilibrium was tested for, using a likelihood-ratio test, whose empirical distribution was obtained by a permutation procedure under a null distribution of no association between the loci (linkage equilibrium) (Slatkin and Excoffier 1996). The number of fathers responsible for the progeny arrays was estimated using GERUD2.0 (Jones 2005) and a subset of the multilocus genotyping data (broods with evidence of null alleles in the maternal genotype were excluded from the analysis). Allele-frequency data were used to calculate exclusion probabilities and to rank the solutions when more than one unique combination of fathers explained the data.

RESULTS

Inheritance of autosomal markers and the interpretation of data with null alleles:

Adult worms were removed from the host abomasum and gravid females placed in single chambers and cultured in vitro to lay eggs. Hence single female worms and their progeny could be genotyped as a brood to directly study the inheritance of the microsatellite markers even though the paternal genotypes were unknown. Five single MHc03(ISE) and five single MHc04(WRS) H. contortus female worms with between 10 and 17 L1 larvae from each of their respective broods were genotyped with seven previously characterized autosomal microsatellite markers. Illustrative examples of the data are given in Table 1 and the full data set with individual genotypes is supplied in supplemental Tables S1A–S1J. The first observation is the presence of alleles in the progeny that are not present in the maternal genotype in all 10 broods for multiple markers, demonstrating the contribution of paternal genotypes in all broods. This is consistent with the generally held view that this parasite undergoes dioecious sexual reproduction as opposed to parthenogenesis or other forms of selfing such as hermaphroditism. A very small number of progeny (11 of 134) contained alleles present only in the maternal genotype. While it is not possible to discount these progeny being the result of rare parthenogenetic or hermaphroditic events occurring concurrently with sexual reproduction, these results are instead likely to simply reflect the limitations of the marker panel polymorphism.

TABLE 1.

Examples to illustrate the interpretation of maternal and progeny genotype data for autosomal markers and the determination of the minimum number of paternal alleles per brood

| Example A: | Example B: | Example C: | Example D: | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MHco4(WRS) female 2 brood, marker Hcms25

|

MHco4(WRS) female 3 brood, marker Hcms8a20

|

MHco4(WRS) female 4 brood, marker Hcms25

|

MHco4(WRS) female 3 brood, marker Hcms 40

|

|||||||||

| Allele 1 | Allele 2 | Inferred paternal alleles | Allele 1 | Allele 2 | Inferred paternal alleles | Allele 1 | Allele 2 | Inferred paternal alleles | Allele 1 | Allele 2 | Inferred paternal alleles | |

| Observed maternal genotypea | 207 | 213 | 240 | 211 | — | |||||||

| Observed genotype of progenya | ||||||||||||

| 1 | 213 | 211 | 211 | 240 | 248 | 248 | 211 | 213 | 213 | 297 | 297 | |

| 2 | 213 | 213 or null | 240 | 244 | 244 | 215 | 215 | 279 | 279 | |||

| 3 | 207 | 207 or null | 240 | 248 | 248 | 213 | 213 | 281 | 281 | |||

| 4 | 207 | 217 | 217 | 240 | 248 | 248 | 211 | 213 | 213 | — | Null | |

| 5 | 213 | 213 or null | 240 | 244 | 244 | 213 | 213 | 279 | 279 | |||

| 6 | 213 | 211 | 211 | 240 | 240 or null | 211 | 211 or null | 279 | 279 | |||

| 7 | 213 | 213 or null | 240 | 244 | 244 | — | Null | 279 | 279 | |||

| 8 | 207 | 207 or null | 240 | 240 or null | 215 | 215 | 281 | 281 | ||||

| 9 | 213 | 209 | 209 | 240 | 240 or null | 211 | 213 | 213 | 297 | 297 | ||

| 10 | 207 | 211 | 211 | 240 | 240 or null | 211 | 211 or null | — | Null | |||

| 11 | ND | ND | ND | 240 | 244 | 244 | 211 | 211 or null | 279 | 279 | ||

| 12 | ND | ND | ND | 240 | 240 or null | 211 | 211 or null | — | Null | |||

| True maternal genotypeb | 207 | 213 | 240 | 240 | 211 | Null | Null | Null | ||||

| Paternal alleles present in brood | 207 or null | |||||||||||

| 209 | 240 or null | 211 or null | 279 | |||||||||

| 211 | 244 | 213 | 297 | |||||||||

| 213 or null | 248 | 215 | 281 | |||||||||

| 217 | Null | Null | ||||||||||

| Minimum no. of paternal alleles | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | ||||||||

Example A: maternal genotype heterozygous for two observed alleles of different size. Example B: maternal genotype homozygous for a single observed allele. Example C: maternal genotype heterozygous for a single observed allele and a null allele. Example D: maternal genotype homozygous for a null allele. —, no alleles amplified from the individual (homozygous for the null allele). ND, not done; only 10 progeny were genotyped from this brood.

Genotypes are based on size of alleles detected by “Genescan.” Where a single allele is observed, this could be either because the individual is homozygous for that allele or alternatively because it is heterozygous for the observed allele and a null allele. Examination of progeny genotypes allows these two possibilities to be discriminated for the maternal genotype.

This is the actual genotype of the mother determined from its observed genotype and taking into account the genotypes of the progeny.

The extremely high level of sequence polymorphism in this parasite, in common with several closely related species, results in the vast majority of markers having a relatively high frequency of null alleles in most populations (Otsen et al. 2000b; Johnson et al. 2006; Grillo et al. 2007; Redman et al. 2008). This has specifically been shown to be the case for the seven autosomal markers used here in the H. contortus MHco3(ISE) and MHco3(WRS) isolates (Redman et al. 2008). The term “null allele” is used here in the population genetic sense to denote an allele of a molecular marker that fails to amplify by PCR. This has to be taken into account when interpreting the inheritance of these markers since an individual worm could have one of four possible genotypes based on a Genescan trace: (i) a heterozygote with two observed alleles of different sizes, (ii) a true homozygote for a single observed allele, (iii) a heterozygote with a single observed allele together with a null allele, and (iv) a homozygote for two null alleles. The full data set of maternal and brood genotypes is entirely consistent with this interpretation. An example of genotyping data for a single marker for each of the four types of maternal genotype is given in Table 1 (examples A, B, C, and D, respectively). In the case of genotype class i, where the maternal genotype is heterozygous for two different-sized observed alleles, each individual progeny in the brood contains a maternal allele as predicted for simple Mendelian inheritance; that is, each progeny contains either a 207 allele or a 213 allele in example A (Table 1). The ratio of these alleles in the broods cannot be predicted precisely because the paternal genotype(s) is not known and may also include alleles of these sizes. In the case of genotype classes ii and iii, which appear identical on Genescan analysis (as a single observed allele), the actual maternal genotype can be determined by examination of the genotypes of the progeny in the brood. To illustrate, only a single allele can be detected in the adult female maternal genotype in examples B and C of sizes 240 and 211, respectively (Table 1). In example B, the maternal genotype must be homozygous for the 240 allele because all the progeny in the brood carry that allele. In contrast, in example C the maternal genotype must be heterozygous for the 211 allele and a null allele since a number of progeny do not carry a 211 allele. In all cases these progeny have only a single observed allele, consistent with their maternally derived allele being null (Table 1, example C). Occasional homozygous null individuals are seen in such broods. In the case of genotype class iv, of which there were only a few cases in the full data set, no allele was observed in the maternal genotype. Consistent with the interpretation of these being true null homozygotes, no heterozygote progeny were detected in such broods, consistent with the inheritance of a null allele from the maternal side (Table 1, example D).

All of the brood/marker combinations in the full data set are consistent with the interpretations of one of the genotype classes illustrated by the four examples in Table 1 (full data set supplied in supplemental Tables S1A–S1J). Hence the genetic analysis with the panel of seven autosomal markers is consistent with obligate dioecious sexual reproduction with simple Mendelian inheritance and the presence of null alleles with all markers.

Inheritance of autosomal markers reveals polyandrous mating in H. contortus:

The paternal allele for each of the individual progeny in a brood can be inferred by taking into account the maternal genotype (Table 1). In some cases, there is only one possible paternal allele; e.g., for progeny no. 1 in example A, the 213 allele must be the maternal allele and the 211 must be the paternal allele (Table 1). In other cases there is a choice of two possible paternal alleles. This occurs in two situations. First, when the progeny genotype is heterozygous and identical to the maternal genotype, either of the two alleles could be of paternal origin. Second, since there are null alleles in the populations, when the progeny genotype has a single allele detected on Genescan the paternal allele could either be the one observed or a null allele; e.g., the paternal allele in progeny no. 2 in example A could be either 213 or a null allele (Table 1). Although this means that the exact number of paternal alleles present in each brood cannot be calculated, it is possible to determine the minimum number for each marker (Table 1). In all the broods examined, there were more than two paternal alleles present for at least two different markers, clearly demonstrating multiple paternity for each brood (Table 2). For all 10 broods, a minimum of either two or three male parents must have contributed to each brood (Table 2). Clearly, the actual number of paternal genotypes could be higher than this since these are the most conservative estimates. There are a number of methods available to calculate the minimum number of unshared parents for half-sib progeny using multilocus genotypes to infer possible paternal haplotypes (Fiumera et al. 2001; Jones 2005). However, application of these did not increase the estimates of the minimum number of male parents since the resolution of these approaches is limited by the presence of null alleles and also the number of alleles per marker (data not shown).

TABLE 2.

Minimum number of paternal alleles for each autosomal marker in each brood

| Minimum no. of paternal alleles in progenya

|

Minimum no. of males mating with female | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brood | Hcms25 | Hcms27 | Hcms33 | Hcms36 | Hcms40 | Hcms22c03 | Hcms8a20 | |

| MHco3(ISE) | ||||||||

| 1 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 2 |

| 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2 |

| 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 2 |

| 4 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 2 |

| 5 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 2 |

| Minimum no. of paternal alleles in progenya

|

Minimum no. of males mating with female | |||||||

| Brood | Hcms25 | Hcms27 | Hcms33 | Hcms36 | Hcms40 | Hcms22c03 | Hcms8a20 | |

| MHco4(WRS) | ||||||||

| 1 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| 2 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| 3 | 4 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 3 |

| 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 3 |

| 5 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 |

Calculated as illustrated in Table 1 using the data set supplied in supplemental Tables A1A–S1J.

Development of a panel of microsatellite markers on a H. contortus X chromosome fragment and determination of the sex chromosome karyotype:

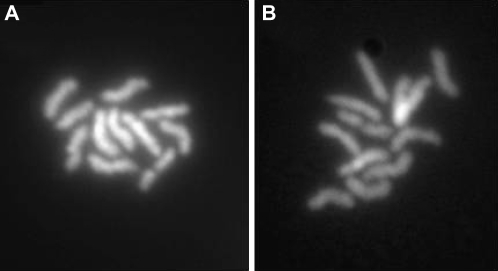

Mitotic metaphase spreads revealed that ∼50% of early MHco3(ISE) H. contortus embryos contained 11 and 50% contained 12 evenly sized chromosomes (17 and 13 embryos, respectively, n = 30) (Figure 1). This confirms that the MHco3(ISE) isolate, which is being used for the H. contortus genome sequencing project, has the same cytological karyotype as much earlier reports on this parasite using a different isolate (Bremner 1954, 1955). This result is consistent with an autosomal karyotype of 5 chromosome pairs and a sex chromosome karyotype of two X chromosomes in females (XX) and a single X chromosome in the male (XO).

Figure 1.—

Examples of DAPI-stained mitotic metaphase spreads of early H. contortus embryos. (A) Embryo containing 11 chromosomes. (B) Embryo containing 12 chromosomes (ends of 2 of the chromosomes overlap in this specimen).

We set out to develop a panel of microsatellite markers located on the X chromosome to undertake genetic analysis of the chromosomal basis of sex determination in H. contortus. A 408,911-bp contiguous stretch of H. contortus sequence has been assembled from five overlapping fully finished BAC insert sequences (K. Mungal, M. Rajandream, M. Quail, A. Coughlan, J. S. Gilleard and M. Berriman, unpublished data; sequence available at ftp://ftp.sanger.ac.uk/pub/pathogens/Haemonchus/contortus/genome/X_chromosome_fragment/). Comparative analysis with C. elegans suggests that this segment of the H. contortus genome is syntenic with the C. elegans X chromosome. This bioinformatic analysis involved a BLASTX search of this H. contortus contig against the C. elegans Wormpep database. To limit our comparative analysis to genes likely to be orthologous between the two species, BLASTX hits were considered only where there was a clear hit to a single C. elegans gene. Where BLASTX hits to several different C. elegans loci were found, these data were considered ambiguous and not used for the purpose of this analysis. This was to avoid confusion due to possible paralogous relationships between H. contortus and C. elegans genes and to limit the analysis only to likely orthologous relationships (see materials and methods for further details). Detailed annotations of this H. contortus genome sequence and its comparative analysis with C. elegans are to be presented separately. The key point, from the perspective of this genetic study, was that 14 of the 17 putative orthologous genes were located on the C. elegans X chromosome, suggesting this 408,911-bp contig was a section of the H. contortus X chromosome (summary of Blast search results supplied in supplemental Table S2).

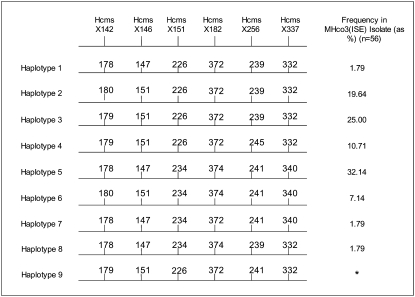

Simple sequence repeats were identified on this contiguous sequence using Tandem Repeat Finder software (Benson 1999) and six microsatellites that were polymorphic in the MHco3(ISE) population were selected as genetic markers (Table 3). These markers were spread across a region of 195,381 bp of sequence within the 408,911-bp contig. Fifty-six adult male MHco3(ISE) worms (55 of which had been previously found to be heterozygous for one or more of the autosomal markers) were genotyped and found to be monomorphic for all six of the putative X-linked markers. No male worms were identified as heterozygous for even a single marker as reflected in zero values for observed heterozygosity (Ho) (Table 3; individual genotypes are supplied in supplemental Table S3A). This demonstrates that male worms are haploid for this genomic fragment, supporting the bioinformatic analysis in suggesting this is an X chromosome fragment and that male worms have an XO sex chromosome karyotype. Since only a single copy of this X chromosome fragment is present in male worms, assignment of haplotypes for the six tightly linked markers is unambiguous, allowing eight different haplotypes to be identified and their relative frequencies estimated in the population of 56 MHco3(ISE) male worms (Figure 2; individual genotypes also supplied in supplemental Table S3A).

TABLE 3.

Summary data for the six H. contortus microsatellite markers on the X chromosome fragment

| Marker | Position on 408,911-bp contig (bp) | Repeat sequence | Primer sequences (5′ → 3′) | Sizes of alleles (bp) in MHco3(ISE) isolate | Hea | Hob | Hoc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HcmsX142 | 142,492–142,517 | TTTG TTTA (TTTG)3 TTTC TT | F: ATTTCCAGGGCTACGTAGTCC | 178, 179, 180 | 0.663 | 0 | 0.6 |

| R: AAGTTTCCACTGAGTCAGTGC | |||||||

| HcmsX146 | 146,936–146,956 | (CTTT)5 C | F: CAATTGTACGATGATCGCCTG | 147, 151 | 0.479 | 0 | 0.433 |

| R: CAACTGTCACACACGCATAGC | |||||||

| HcmsX151 | 151,062–151,089 | (GT)7 GCT GT GG (GT)3 G | F: CAGATTGTCGTCTAGTGGCTG | 226, 234 | 0.499 | 0 | 0.467 |

| R: GTCATCTTCTCTTCGTCGTCC | |||||||

| HcmsX182 | 182,741–182,769 | TAAGAGG TATAAGG (TAAGAGG)2 T | F: GACACTTCAAGCTGTTCAGTG | 372, 374 | 0.485 | 0 | 0.5 |

| R: GCGATGGTGAGCAAATTGAGC | |||||||

| HcmsX256 | 256,792– 256,824 | (TG)3 TC TG TA GG TG TA (TG)3 GG (TG)3 T | F: TCACTCGTCACAAATCACACG | 239, 241, 245 | 0.569 | 0 | 0.467 |

| R: GTCGTTGTAACTCGTTGACC | |||||||

| HcmsX337 | 337,830–337,873 | TTTCA TTTCAC TTGCAT TTTCAT TCTTCATT TTTCTT TCTTCAT | F: GTTGGCATTTCCTGTCATACG | 332, 340 | 0.478 | 0 | 0.465 |

| R: TTTAGTGTCAGCGCCTGTTTC |

Expected heterozygosity based on allele frequencies in total adult MHco3(ISE) population (56 male worms plus 30 female worms).

Observed heterozygosity based on genotyping 56 MHco3(ISE) adult male worms.

Observed heterozygosity based on genotyping 30 MHco3(ISE) adult female worms.

Figure 2.—

Haplotypes of the six X-linked microsatellite markers and their relative frequencies in the MHco3(ISE) isolate based on genotyping 56 adult male H. contortus worms. Numbers represent the alleles of each marker (marker names are shown across the top). *, haplotype 9 was not identified in the original 56 male worms genotyped but was identified in the progeny of MHco3(ISE) adult female 2 (see supplemental Table S4B). It is not unexpected that some rarer haplotypes may not have been represented in the 56 male worms originally genotyped.

The heads of 30 individual adult female MHco3(ISE) worms were also genotyped with these markers. In the case of the female worms, the observed heterozygosity values(Ho) closely matched the expected heterozygosity values (He) on the basis of the allele frequencies in the population. This suggests the X chromosome fragment is diploid in female worms (Table 3; individual genotypes supplied in supplemental Table S3B). All 15 pairwise combinations of the six markers were found to be in linkage disequilibrium at significance levels <P = 0.0001, using the likelihood-ratio test in Arlequin ver3.11 on the female genotype data (Excoffier and Slatkin 1995). By comparison, none of the 21 pairwise combinations of the seven autosomal markers were found be in linkage disequilibrium even at a significance level of 0.01. This confirmed the tight genetic linkage of the six markers, as expected by their location across a contiguous stretch of 195,381 bp of sequence, and supports their analysis as co-inherited haplotypes as opposed to separate independent markers (as was the case for the autosomal markers). Of the 30 female worms genotyped, 21 were heterozygous for one or more of the six markers, demonstrating they were diploid for the X chromosome fragment (individual genotypes supplied in supplemental Table S3B). The phase of the alleles of each marker is unknown in these heterozygous females and so, unlike in the case of male worms, the precise identity of the haplotypes present in each individual cannot be definitively determined. However, the remaining 9 adult female worms that were genotyped were monomorphic for all six markers and so in these cases the haplotypes can be unambiguously assigned: 4 individuals were homozygous for haplotype 5, 3 individuals were homozygous for haplotype 3, and 2 individuals were homozygous for haplotype 2 (individual genotypes supplied in supplemental Table S3). Assuming Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium, the proportion of female worms that were homozygous for these haplotypes is consistent with the number expected for diploid individuals, on the basis of the haplotype frequencies present in the MHco3(ISE) population (Figure 2); e.g., P = 0.321 for haplotype 5, hence P2 = 0.103, and so ∼10% of diploid individuals are expected to be homozygous for this haplotype.

Hence the genetic data all support the 408,911-bp contig being located on the X chromosome and the H. contortus male and female sex chromosome karyotypes being XO and XX, respectively.

Use of X chromosome haplotypes to analyze polyandry:

The ability to study the inheritance of a series of tightly linked co-inherited markers with a defined set of haplotypes provides an additional approach to investigate the mating pattern of H. contortus. Determination of the number of different paternal X chromosome fragment haplotypes in a brood from a single female provides a direct measure of the number of different male parents that have contributed to the brood. To undertake this analysis, four of the MHco3(ISE) female worms that were previously genotyped with the autosomal markers were genotyped with the six linked markers on the X chromosome fragment [the brood of MHco3(ISE) female 3 was not included since the template had been exhausted by the autosomal marker genotyping]. An example of the genotyping data is given in Table 4 and the full data set is provided in supplemental Table S4A–S4D. In analyzing the data, the progeny that are monomorphic for all six markers were considered first. These must be either male worms (which contain only a single X chromosome) or female worms that are homozygous for a particular haplotype. In either case the haplotypes present in monomorphic progeny must correspond to the two maternal haplotypes. In the case of male progeny this is because, in an XX/XO sex determination system, the male worms inherit an X chromosome only from the maternal parent. In the case of female progeny, although they inherit an X chromosome from each parent, for the individual to be monomorphic at all six markers the two haplotypes must be identical and so correspond to one of the maternal haplotypes. Hence the two maternal haplotypes can be determined from the genotypes of the monomorphic progeny. In the example provided in Table 4, all of the nine monomorphic progeny in the brood of MHco3(ISE) adult female 4 are either haplotype 2 or haplotype 5 and so the maternal genotype must have been heterozygous for these two haplotypes (Table 4). Once the two maternal haplotypes are known, then it is possible to “decode” the haplotypes present in heterozygous progeny. For example, in progeny no. 2 of MHco3(ISE) adult female 4, the inherited maternal haplotype must be haplotype 2 (as haplotype 5 does not “fit”) and so the remaining paternal haplotype must be haplotype 3 (Table 4; refer to Figure 2 for haplotype nomenclature). The results of this analysis for the four MHco3(ISE) broods examined are summarized in Table 5 (full set of individual genotypes supplied in supplemental Tables S4A–S4D). As expected, and further confirming an XX/XO sex determination system, there was a maximum of two different haplotypes represented in the monomorphic progeny of each brood (Table 5). For three of the broods at least three different paternal X-chromosomal haplotypes are present and for the fourth brood at least four different X-chromosomal haplotypes are present (Table 5). Hence a minimum of either three or four different male worms must have contributed to these broods, respectively. This confirms the finding of polyandry from the autosomal marker analysis and provides greater discriminatory power, increasing the minimum number of paternal genotypes that must have contributed to each brood.

TABLE 4.

Example to illustrate the determination of the minimum number of paternal X chromosome haplotypes in a brood

| Brood of MHco3(ISE) adult female 4

|

||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HcmsX142

|

HcmsX146

|

HcmsX151

|

HcmsX182

|

HcmsX256

|

HcmsX337

|

|||||||||

| Progeny ID | Allele 1 | Allele 2 | Allele 1 | Allele 2 | Allele 1 | Allele 2 | Allele 1 | Allele 2 | Allele 1 | Allele 2 | Allele 1 | Allele 2 | Haplotype | |

| Observed maternal genotype | 178 | 180 | 147 | 151 | 226 | 234 | 372 | 374 | 239 | 241 | 332 | 340 | ||

| Genotype of brood | ||||||||||||||

| Monomorphic progeny | 1 | 180 | 151 | 226 | 372 | 239 | 332 | 2 | ||||||

| 3 | 178 | 147 | 234 | 374 | 241 | 340 | 5 | |||||||

| 6 | 178 | 147 | 234 | 374 | 241 | 340 | 5 | |||||||

| 8 | 180 | 151 | 226 | 372 | 239 | 332 | 2 | |||||||

| 9 | 180 | 151 | 226 | 372 | 239 | 332 | 2 | |||||||

| 10 | 178 | 147 | 234 | 374 | 241 | 340 | 5 | |||||||

| 11 | 180 | 151 | 226 | 372 | 239 | 332 | 2 | |||||||

| 13 | 178 | 147 | 234 | 374 | 241 | 340 | 5 | |||||||

| 16 | 180 | 151 | 226 | 372 | 239 | 332 | 2 | |||||||

| Maternal haplotypes | 2 | |||||||||||||

| 5 | ||||||||||||||

| Heterozygous progeny | 2 | 179 | 180 | 151 | 226 | 372 | 239 | 332 | 2 and 3 | |||||

| 4 | 178 | 179 | 147 | 151 | 226 | 234 | 372 | 374 | 239 | 241 | 332 | 340 | 5 and 3 | |

| 5 | 178 | 180 | 147 | 151 | 226 | 234 | 372 | 374 | 239 | 241 | 332 | 340 | 2 and 5 | |

| 12 | 178 | 180 | 147 | 151 | 226 | 234 | 372 | 374 | 239 | 241 | 332 | 340 | 2 and 5 | |

| 14 | 178 | 180 | 147 | 151 | 226 | 234 | 372 | 374 | 239 | 241 | 332 | 340 | 2 and 5 | |

| 15 | 179 | 180 | 151 | 226 | 372 | 239 | 245 | 332 | 2 and 4 | |||||

| Paternal haplotypes | 3 | |||||||||||||

| 2 or 5 | ||||||||||||||

| 4 | ||||||||||||||

TABLE 5.

Analysis of X chromosome haplotypes in broods from 4 MHco3(ISE) females

| MHco3(ISE) adult female | Maternal X chromosome haplotypesa | Paternal X chromosome haplotypes in progeny | Minimum no. of male parents contributing to brood |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adult female 1 | 2 and 4 | 1, 3, 5, (2 or 4) | 4 |

| Adult female 2 | 3 | 2, 4, 9b | 3 |

| Adult female 3 | 2 and 5 | 3, 4, (2 or 5) | 3 |

| Adult female 4 | 2 and 3 | 4, 5, (2 or 3) | 3 |

Determined from haplotypes of monomorphic progeny.

Only identified in brood of MHco3(ISE) adult female 2.

DISCUSSION

The genetics and mating patterns of parasitic nematodes are poorly understood and studies have largely been confined to morphology, cytology, and phenotypic analysis of genetic crosses (Walton 1959; Lejambre and Georgi 1970; Le Jambre 1981; Mutafova 1995; Sangster et al. 1998). In some cases there are conflicting reports of basic aspects such as haploid chromosome number (Underwood and Bianco 1999). Although there are an increasing number of population genetic studies, there are very few inheritance studies using molecular markers. The only two published studies of this type involve the proposal of an XX/XY basis of sex determination in Brugia malayi using a single male-specific marker and the confirmation of the XX/XO female/male karyotypes of Strongyloides ratti using an X-linked RFLP marker (Underwood and Bianco 1999; Harvey and Viney 2001).

We studied the inheritance of microsatellite markers to investigate the basic genetics, the chromosomal basis of sex determination, and the mating behavior of the parasitic nematode H. contortus. The inheritance of both autosomal markers and X-linked markers was consistent with an obligate dioecious mode of reproduction with paternal alleles being present in all broods examined. We developed a panel of tightly linked microsatellite markers on a fragment of the H. contortus X chromosome and used it to demonstrate the sex karyotype of this parasite as XO/XX male/female. Previous population genetic studies have found a high frequency of null alleles for the seven autosomal markers used in this study and the inheritance studies presented reflect this (Redman et al. 2008). The presence of null alleles for microsatellite markers is recognized in many organisms (Dakin and Avise 2004; Wagner et al. 2006) but it appears to be particularly marked in H. contortus and related nematodes (Grillo et al. 2006; Johnson et al. 2006; Redman et al. 2008). This phenomenon is likely to be due to high levels of polymorphism in flanking sequences, possibly as a consequence of large population sizes in strongylid nematode species resulting in high levels of genetic variation (Blouin et al. 1995, 1999). Failure to account for null alleles in genetic analysis can lead to erroneous conclusions (Dakin and Avise 2004; Wagner et al. 2006). However, we were able to adjust for their presence by recognizing the fact that certain observed genotypes can represent one of several possible, but defined, true genotypes.

Both the autosomal and the X chromosome markers demonstrate that polyandry occurs in H. contortus with a single female carrying the progeny of between two and four different males. These represent the minimum numbers of different male genotypes that contribute to each brood since the ability to discriminate between individual paternal genotypes is limited by the level of polymorphism of markers and the presence of null alleles. Polyandry is a phenomenon that has been reported in organisms as diverse as mammals, birds, and insects (Jennions and Petrie 2000). However, to our knowledge, this is the first demonstration of polyandry in a parasitic helminth. We have shown that it occurs in two genetically distinct H. contortus isolates, MHco3(ISE) and MHco4(WRS). The infections from which the parasites were obtained in this study were the result of orally dosing sheep with 5000 L3 larvae. This produces infection intensities of adult worms typical of those seen in the heavier worm burdens found in natural infections and so one would predict this is likely to be a common phenomenon in the field. However, it is clearly possible that the extent of polyandry might vary with infection intensity and this will be interesting to examine in future studies. The relative benefits and costs of polyandry in free-living organisms are the subject of much speculation and debate that focus on the potential genetic benefits of female mate choice vs. the costs of multiple mating behavior and these discussions have been reviewed in detail elsewhere (Jennions and Petrie 2000; Tregenza and Wedell 2000). The potential costs of multiple mating in a parasite such as H. contortus might include the expenditure of energy in finding a mate and undertaking copulation, the disruption of feeding behavior, and loss of mucosal attachment. Hence, there must presumably be significant benefits to the parasite to offset these costs and there are a number of possibilities. First, the fecundity of female H. contortus worms is extremely high with a single female worm producing up to 4000 eggs per day and this level of production can be maintained for many weeks (F. Jackson, unpublished data). This is thought to be an important feature of the parasite's epidemiology and is likely to be critical to its ability to adapt to different climatic zones (Waller et al. 2004). This is an extremely high level of zygote production and would require a large and continuous supply of sperm. Hence, repeated, and perhaps indiscriminate, mating might be essential to achieve this biotic potential. Second, a high level of genetic variation is considered to be of benefit to a pathogen by providing the genetic “raw material” to allow an effective response to selection by, for example, the host immune system or drug treatment. H. contortus does indeed show extremely high levels of genetic variation that is considered to be due, at least in part, to its very large population sizes (Blouin et al. 1995; Troell et al. 2006; Gilleard and Beech 2007; Redman et al. 2008). However, polyandry would provide an additional mechanism of generating variation since offspring from a female that has mated with three or four, or perhaps even more, male worms would be much more diverse than those from a single-pair mating. Third, it is possible that polyandry might be a mechanism to minimize the risks of genetically incompatible mating, which has been shown to be the case for a number of free-living organisms (Garcia-Gonzalez and Simmons 2007; Firman and Simmons 2008; Klemme et al. 2008). The huge amounts of sequence polymorphism seen in the H. contortus genome involving both SNPs and indels (J. S. Gilleard, R. N. Beech and M. Berriman, unpublished data) raise the possibility that detrimental recessive mutations could be relatively common in parasite populations. If this were the case, the mating of a female with multiple males would potentially reduce the likelihood of its reproductive failure due to incompatible genotypes.

In summary, this study provides important genetic information and tools required to apply forward genetic analysis to H. contortus. The approaches described here are applicable to other parasitic nematode species but at present the main limitation is the availability of appropriate genetic markers. However, this is likely to become less of an issue in the near future due to the large number of parasitic nematode genome projects that are now underway. Hence there is now an unprecedented opportunity for the application of genetic analysis to this important group of human and animal pathogens.

Acknowledgments

We thank David Bartley, Alison Donnan, and other members of the Veterinary Parasitology Group at the Moredun Institute, Edinburgh for help with parasite propagation and maintenance. We also thank Marie-Adele RajanDream, Karen Mungal, Mike Quail, Avril Coughlin, Sean Humphray, and other members of the Sanger Institute Pathogen Sequencing Unit for continued support and efforts on the H. contortus genome project. We are also grateful to Andrew Tait, University of Glasgow for helpful comments on the manuscript. This work was funded by Wellcome Trust Project grant no. 067811/Z/02/Z.

References

- Anderson, T. J., 2001. The dangers of using single locus markers in parasite epidemiology: Ascaris as a case study. Trends Parasitol. 17 183–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beech, R. N., R. K. Prichard and M. E. Scott, 1994. Genetic variability of the beta-tubulin genes in benzimidazole-susceptible and -resistant strains of Haemonchus contortus. Genetics 138 103–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson, G., 1999. Tandem repeats finder: a program to analyze DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 27 573–580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blouin, M. S., C. A. Yowell, C. H. Courtney and J. B. Dame, 1995. Host movement and the genetic structure of populations of parasitic nematodes. Genetics 141 1007–1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blouin, M. S., J. Liu and R. E. Berry, 1999. Life cycle variation and the genetic structure of nematode populations. Heredity 83(Pt. 3): 253–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bremner, K. C., 1954. Cytological polymorphism in the nematode Haemonchus contortus (Rudolphi 1803) Cobb 1898. Nature 174 704–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bremner, K. C., 1955. Cytological studies on the specific distinctness of the ovine and bovine “strains” of the nematode Haemonchus contortus (Rudolphi) Cobb (Nematoda: Trichostrongylidae). Aust. J. Zool. 3 312–323. [Google Scholar]

- Couthier, A., J. Smith, P. McGarr, B. Craig and J. S. Gilleard, 2004. Ectopic expression of a Haemonchus contortus GATA transcription factor in Caenorhabditis elegans reveals conserved function in spite of extensive sequence divergence. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 133 241–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Criscione, C. D., J. D. Anderson, D. Sudimack, W. Peng, B. Jha et al., 2007. Disentangling hybridization and host colonization in parasitic roundworms of humans and pigs. Proc. Biol. Sci. 274 2669–2677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dakin, E. E., and J. C. Avise, 2004. Microsatellite null alleles in parentage analysis. Heredity 93 504–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, H. M., and H. R. Horvitz, 1986. Genetic control of programmed cell death in the nematode C. elegans. Cell 44 817–829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Excoffier, L., and S. Schneider, 2005. Arlequin ver. 3.0: an integrated software package for population genetics data analysis. Evol. Bioinform. Online 1 47–50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Excoffier, L., and M. Slatkin, 1995. Maximum-likelihood estimation of molecular haplotype frequencies in a diploid population. Mol. Biol. Evol. 12 921–927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Firman, R. C., and L. W. Simmons, 2008. Polyandry facilitates postcopulatory inbreeding avoidance in house mice. Evol. Int. J. Org. Evol. 62 603–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiumera, A. C., Y. D. DeWoody, J. A. DeWoody, M. A. Asmussen and J. C. Avise, 2001. Accuracy and precision of methods to estimate the number of parents contributing to a half-sib progeny array. J. Hered. 92 120–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Gonzalez, F., and L. W. Simmons, 2007. Paternal indirect genetic effects on offspring viability and the benefits of polyandry. Curr. Biol. 17 32–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilleard, J. S., 2006. Understanding anthelmintic resistance: the need for genomics and genetics. Int. J. Parasitol. 36 1227–1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilleard, J. S., and R. N. Beech, 2007. Population genetics of anthelmintic resistance in parasitic nematodes. Parasitology 134 1133–1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grillo, V., F. Jackson and J. S. Gilleard, 2006. Characterisation of Teladorsagia circumcincta microsatellites and their development as population genetic markers. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 148 181–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grillo, V., F. Jackson, J. Cabaret and J. S. Gilleard, 2007. Population genetic analysis of the ovine parasitic nematode Teladorsagia circumcincta and evidence for a cryptic species. Int. J. Parasitol. 37 435–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, S. C., and M. E. Viney, 2001. Sex determination in the parasitic nematode Strongyloides ratti. Genetics 158 1527–1533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoekstra, R., A. Criado-Fornelio, J. Fakkeldij, J. Bergman and M. H. Roos, 1997. Microsatellites of the parasitic nematode Haemonchus contortus: polymorphism and linkage with a direct repeat. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 89 97–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoekstra, R., M. Otsen, J. A. Lenstra and M. H. Roos, 1999. Characterisation of a polymorphic Tc1-like transposable element of the parasitic nematode Haemonchus contortus. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 102 157–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jennions, M. D., and M. Petrie, 2000. Why do females mate multiply? A review of the genetic benefits. Biol. Rev. Camb. Philos. Soc. 75 21–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, P. C., L. M. Webster, A. Adam, R. Buckland, D. A. Dawson et al., 2006. Abundant variation in microsatellites of the parasitic nematode Trichostrongylus tenuis and linkage to a tandem repeat. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 148 210–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones, A. G., 2005. GERUD 2.0: a computer program for the reconstruction of parental genotypes from half-sib progeny arrays with known or unknown parents. Mol. Ecol. Notes 5 708–711. [Google Scholar]

- Klemme, I., H. Ylonen and J. A. Eccard, 2008. Long-term fitness benefits of polyandry in a small mammal, the bank vole Clethrionomys glareolus. Proc. Biol. Sci. 275 1095–1100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knox, D. P., D. L. Redmond, G. F. Newlands, P. J. Skuce, D. Pettit et al., 2003. The nature and prospects for gut membrane proteins as vaccine candidates for Haemonchus contortus and other ruminant trichostrongyloids. Int. J. Parasitol. 33 1129–1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Jambre, L. F., 1977. Genetics of vulvar morph types in Haemonchus contortus: Haemonchus contortus cayugensis from the Finger Lakes Region of New York. Int. J. Parasitol. 7 9–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Jambre, L. F., 1981. Hybridization of Australian Haemonchus placei (Place, 1893), Haemonchus contortus cayugensis (Das & Whitlock, 1960) and Haemonchus contortus (Rudolphi, 1803) from Louisiana. Int. J. Parasitol. 11 323–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeJambre, L. F., and J. R. Georgi, 1970. Influence of fertilization on ovogenesis in Ancylostoma caninum. J. Parasitol. 56 131–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Jambre, L. F., W. M. Royal and P. J. Martin, 1979. The inheritance of thiabendazole resistance in Haemonchus contortus. Parasitology 78 107–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Jambre, L. F., I. J. Lenane and A. J. Wardrop, 1999. A hybridisation technique to identify anthelmintic resistance genes in Haemonchus. Int. J. Parasitol. 29 1979–1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Jambre, L. F., J. H. Gill, I. J. Lenane and P. Baker, 2000. Inheritance of avermectin resistance in Haemonchus contortus. Int. J. Parasitol. 30 105–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller, D. M., and D. C. Shakes, 1995. Immunofluorescence microscopy. Methods Cell Biol. 48 365–394. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mutafova, T., 1995. Meiosis and some aspects of cytological mechanisms of chromosomal sex determination in nematode species. Int. J. Parasitol. 25 453–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nei, M., 1978. Estimation of average heterozygosity and genetic distance from a small number of individuals. Genetics 89 583–590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nejsum, P., E. D. Parker, Jr., J. Frydenberg, A. Roepstorff, J. Boes et al., 2005. Ascariasis is a zoonosis in Denmark. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43 1142–1148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otsen, M., M. E. Plas, J. Groeneveld, M. H. Roos, J. A. Lenstra et al., 2000. a Genetic markers for the parasitic nematode Haemonchus contortus based on intron sequences. Exp. Parasitol. 95 226–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otsen, M., M. E. Plas, J. A. Lenstra, M. H. Roos and R. Hoekstra, 2000. b Microsatellite diversity of isolates of the parasitic nematode Haemonchus contortus. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 110 69–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raymond, M., and F. Rousset, 1995. An exact test for population differentiation. Evolution 49 1280–1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redman, E., E. Packard, V. Grillo, J. Smith, F. Jackson et al., 2008. Microsatellite analysis reveals marked genetic differentiation between Haemonchus contortus laboratory isolates and provides a rapid system of genetic fingerprinting. Int. J. Parasitol. 38 111–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sangster, N. C., J. M. Redwin and H. Bjorn, 1998. Inheritance of levamisole and benzimidazole resistance in an isolate of Haemonchus contortus. Int. J. Parasitol. 28 503–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slatkin, M., and L. Excoffier, 1996. Testing for linkage disequilibrium in genotypic data using the expectation-maximization algorithm. Heredity 76(Pt. 4): 377–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su, X., K. Hayton and T. E. Wellems, 2007. Genetic linkage and association analyses for trait mapping in Plasmodium falciparum. Nat. Rev. Genet. 8 497–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tait, A., D. Masiga, J. Ouma, A. MacLeod, J. Sasse et al., 2002. Genetic analysis of phenotype in Trypanosoma brucei: a classical approach to potentially complex traits. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 357 89–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tregenza, T., and N. Wedell, 2000. Genetic compatibility, mate choice and patterns of parentage: invited review. Mol. Ecol. 9 1013–1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troell, K., A. Engstrom, D. A. Morrison, J. G. Mattsson and J. Hoglund, 2006. Global patterns reveal strong population structure in Haemonchus contortus, a nematode parasite of domesticated ruminants. Int. J. Parasitol. 36 1305–1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Underwood, A. P., and A. E. Bianco, 1999. Identification of a molecular marker for the Y chromosome of Brugia malayi. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 99 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, A. P., S. Creel and S. T. Kalinowski, 2006. Estimating relatedness and relationships using microsatellite loci with null alleles. Heredity 97 336–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waller, P. J., L. Rudby-Martin, B. L. Ljungstrom and A. Rydzik, 2004. The epidemiology of abomasal nematodes of sheep in Sweden, with particular reference to over-winter survival strategies. Vet. Parasitol. 122 207–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walton, A. C., 1959. Some parasites and their chromosomes. J. Parasitol. 45 1–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wimmer, B., B. H. Craig, J. G. Pilkington and J. M. Pemberton, 2004. Non-invasive assessment of parasitic nematode species diversity in wild Soay sheep using molecular markers. Int. J. Parasitol. 34 625–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]