Abstract

Many larval color mutants have been obtained in the silkworm Bombyx mori. Mapping of melanin-synthesis genes on the Bombyx linkage map revealed that yellow and ebony genes were located near the chocolate (ch) and sooty (so) loci, respectively. In the ch mutants, body color of neonate larvae and the body markings of elder instar larvae are reddish brown instead of normal black. Mutations at the so locus produce smoky larvae and black pupae. F2 linkage analyses showed that sequence polymorphisms of yellow and ebony genes perfectly cosegregated with the ch and so mutant phenotypes, respectively. Both yellow and ebony were expressed in the epidermis during the molting period when cuticular pigmentation occurred. The spatial expression pattern of yellow transcripts coincided with the larval black markings. In the ch mutants, nonsense mutations of the yellow gene were detected, whereas large deletions of the ebony ORF were detected in the so mutants. These results indicate that yellow and ebony are the responsible genes for the ch and so loci, respectively. Our findings suggest that Yellow promotes melanization, whereas Ebony inhibits melanization in Lepidoptera and that melanin-synthesis enzymes play a critical role in the lepidopteran larval color pattern.

THE extremely diverse lepidopteran color pattern is evolutionarily interesting because of its association with natural selection. Much research has focused on adult wings to study the molecular mechanisms of color patterns. Some of the most convincing data comes from comparative studies between different species (Carroll et al. 1994; Brunetti et al. 2001; Reed and Serfas 2004; Monteiro et al. 2006), phenotypically differentiated laboratory strains, or spontaneous mutants within species (Brakefield et al. 1996; Brunetti et al. 2001, Beldade et al. 2002). A candidate gene approach revealed that the Distal-less gene segregates with the eyespot size phenotype, explaining up to 20% of the phenotypic difference between the selected lines in Bicyclus anynana (Beldade et al. 2002). To determine the responsible genes for color pattern polymorphisms or mutants, an AFLP-based linkage map has been developed in several butterfly species (reviewed in Beldade et al. 2008). Recently, the linkage of forewing color pattern and mate preference with the wingless gene in two Heliconius species (Kronforst et al. 2006) and the linkage of the mimicry locus H with the invected gene in Papilio dardanus have been reported (Clark et al. 2008), although these reports have not elucidated whether wingless or invected is the responsible gene for wing color pattern variation. Until now, no color pattern genes have been elucidated by positional cloning in Lepidoptera.

Like the adult wings, the larvae of butterflies and moths, often preyed on by other animals, also show various color patterns. In the swallowtail butterfly, Papilio xuthus, several melanin-synthesis genes are associated with stage-specific larval color patterns (Futahashi and Fujiwara 2005, 2006, 2007, 2008a). Melanin-synthesis genes are responsible for pigmentation mutants in Drosophila melanogaster (Wright 1987; Wittkopp et al. 2002a); however, the connection between these genes and the color pattern mutants in other insects has not been elucidated.

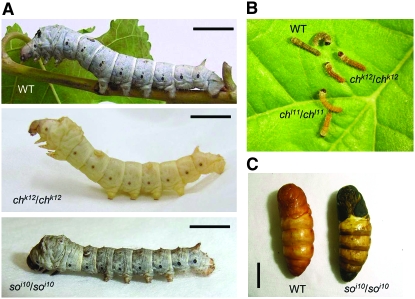

Although larval color variations are often observed in many Lepidoptera, the genes responsible for color patterns have not yet been identified by mutation studies. Elucidating the genetic basis of lab-generated color mutants is important because it points out the interacting loci in the pathway that produces interesting phenotypes (larval pigmentation in this case) and it highlights genetic changes that could serve as the raw material for evolutionary change. Among lepidopteran species, the silkworm Bombyx mori is the most suitable for identification of mutants because its genome is already available (Mita et al. 2004; Xia et al. 2004); a high-density linkage map has been constructed between p50T and C108T strains (Yamamoto et al. 2006, 2008); and many available color mutants, especially in larval stages, have been obtained (Banno et al. 2005). Here we have analyzed whether melanin-synthesis genes were associated with Bombyx larval color mutants by using linkage analysis and comparing protein structure between wild-type and mutant strains. These genes are predicted to be important for driving patterns of pigmentation that may be used as a mechanism to avoid being preyed upon. Linkage analysis revealed perfect cosegregation between the chocolate (ch) locus and the yellow gene and between the sooty (so) locus and the ebony gene. The spontaneous ch mutant was first reported in Toyama (1909) and was mapped at 9.6 cM of the silkworm genetic linkage group 13 (Suzuki 1942; Banno et al. 2005). In the recessive homozygote of the ch mutant, the larval skin and the head cuticle of newly hatched larvae is reddish brown instead of the normal black (Figure 1B). In grown larvae of the homozygous ch mutants, black body markings and sieve plates of spiracles remain reddish brown (Figure 1A). The so is also a spontaneous mutant (Tanaka 1924) and was mapped at the end of the silkworm genetic linkage group 26 (Banno et al. 1989, 2005). In the recessive homozygote of the so mutant, the pupal color is black, especially at the ventral tip of the abdomen (Figure 1C). From larvae to the adult stage, body color is smoky, but less conspicuous compared to pupae (Figure 1A). Molecular characterization of these pigmentation mutants demonstrated that ch mutants were loss-of-function yellow alleles caused by a deletion or a presumptive splice junction mutation, while the so mutants were loss-of-function ebony alleles caused by deletions present in 3′ exons, suggesting that these two genes were responsible for the black color pattern common among insects.

Figure 1.—

(A) Lateral view of the fifth instar larva of silkworm B. mori. Wild type (+p strain, top), chocolate mutant (chk12, middle), and sooty mutant (soi10, bottom) are shown. Bars, 1 cm. (B) The B. mori neonate larvae of wild-type (p50T strain) and chocolate mutants (chl11 and chk12). The body color of wild type (WT) is brownish black while that of ch mutants is reddish. (C) Pupal black phenotype of sooty mutant (right). Bar, 1 cm.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Silkworm strains:

The chk12, chl11, soi10, and soi41 mutant strains were provided from the silkworm stock center of Kyushu University supported by the National BioResource Project. The silkworms were reared with mulberry leaves or artificial diets (Nihon Nosan Kogyo, Yokohama, Japan) under a 16-hr-light:8-hr-dark photoperiod at 25°. The staging of the molting period was based on the spiracle index, which represented the characteristic sequence of new spiracle formation (Kiguchi and Agui 1981).

Mapping and linkage analysis:

For the linkage map construction, we have developed web-based in-house software designed to assist positional cloning in silkworm genomic research. This is a Perl-based Common Gateway Interface program. This program requires BioPerl (Stajich et al. 2002), BLAST (Altschul et al. 1997), primer3 (Rozen and Skaletsky 2000), and RepeatMasker (http://www.repeatmasker.org/). After checking the validity of the query sequence, BLAST search of the query sequence against the silkworm genomic sequence database was performed (Mita et al. 2004; Xia et al. 2004). The repeat sequence masking of the sequence was internally performed with RepeatMasker previous to primer design with primer3. Single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP), including small base insertions and deletions, were identified using the above primers. We designed two primer sets for each gene and used the following polymerase chain reaction (PCR) primer pairs: 5′-TGATGCTACTGACTGACCTTGA-3′ and 5′-TAACTTGATGCAAATGGTATTTTT-3′ for TH, 5′-AGTCCGCTATCTTGTCTAATGAACTAGGTG-3′ and 5′-ATAACTCCGTTTCTGTATGAAAGAAGGACA-3′ for DDC, 5′-GAGACGAAACTAAAGTGAAAGGTTCCTA-3′ and 5′-CAACAATCTTGTACCGACCTAGTACTTAT-3′ for yellow, 5′-CTAACAACTGCCATTCTCTTAGCATGATTT-3′ and 5′-TGCTCTTTCGAACAGAAAAATAGAACGTAT-3′ for ebony (SNP 1), and 5′-CAAGCTTAAACCTTCGAGGAGAACTACTTT-3′ and 5′-CGACACAGATTAACCTGAACAATGAATACT-3′ for ebony (SNP 2). Segregation patterns of SNPs were surveyed using 190 first-generation backcross (BC1) individuals from a single pair mating between a p50T female and an F1 male (p50T female × C108T male) as previously reported (Yamamoto et al. 2006, 2008). Segregation patterns were analyzed using Mapmaker/exp (version 3.0; Lander et al. 1987) with the Kosambi mapping function (Kosambi 1944).

The linkage analysis between the ch locus and yellow gene was estimated by SNP analysis. The cross that showed tight linkage between yellow and chk12 was an F2 intercross (heterozygous F1 females mated to F1 heterozygous males). Genomic DNA was extracted from the parent moths, F1 moths, and F2 larvae (first instar). A genomic fragment of the yellow gene was amplified by PCR with the following primers: 5′-CTCGTGTCGCAAGACGGATAGC-3′ and 5′-CCTTGTGTAGCGACCATGTCAC-3′. The linkage analysis between the so locus and ebony gene was estimated on the basis of the length of the PCR fragment of the ebony gene. The cross that showed tight linkage between ebony and soi41 was a backcross (so mutant female mated to an F1 heterozygous male). Genomic DNA was extracted from the parent moths, F1 moths, and F2 pupae. A genomic fragment of the ebony gene was amplified by PCR with the following primers: 5′-CGTGGTGCTATGCTACGGTT-3′ and 5′-TTGCCGTTTACCAGCAGAGG-3′.

Cloning of yellow and ebony cDNAs:

Total RNA was isolated from several tissues by the TRI-reagent kit (Sigma, St. Louis) and reverse transcribed with random primer (N6) by the first-strand cDNA synthesis kit (Amersham, Sunnyvale, CA). The full-length cDNA was obtained by rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE) technique using the Marathon cDNA amplification kit (Clontech, Mountain View, CA). The following primers were used: 5′-GCTGGACACCGGAGTCGTCCATTAC-3′ for 5′ RACE of yellow, 5′-TGCCAACATCGCTCTCGATATCG-3′ and 5′-CCGATGAACTGGGCTATGGTCTTATC-3′ for 3′ RACE of yellow, 5′-ACGGGTCGGGCTCAACTCCTCATC-3′ and 5′-GGGTACAAATCCAATTGGTCGCTGCCT-3′ for 5′ RACE of ebony, and 5′-CGCACAGGAGATTTCGGGACTCTTG-3′ and 5′-GACACCGCGTGGATCTGCTGGAAGT-3′ for 3′ RACE of ebony. PCR was performed using ExTaq (TaKaRa) under the following conditions: 35 cycles at 94° for 30 sec, 55° for 30 sec, and 72° for 90 sec. The PCR products were subcloned into pGEM-T Easy Vector (Promega, Madison, WI) and sequenced by an ABI3130xl genetic analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA).

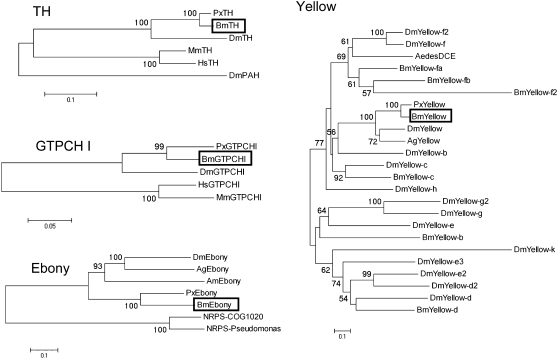

Phylogenetic analysis:

To investigate whether we obtained the genuine orthologs of melanin-synthesis genes in B. mori, we performed phylogenetic analysis using several related genes. The sequences used to create the diagram are listed in Table 1. Sequences were aligned using Clustal_X (Thompson et al. 1997). Phylogenetic trees were constructed by the neighbor-joining method with the MEGA4 program (Tamura et al. 2007). The confidence of the various phylogenetic lineages was assessed by the bootstrap analysis.

TABLE 1.

Abbreviation table of proteins used in the neighbor-joining tree in Figure 2

| Abbreviation | Species | Gene | Accession no. |

|---|---|---|---|

| PxTH | P. xuthus | Tyrosine hydroxylase | AB178006 |

| BmTH | B. mori | Tyrosine hydroxylase | AB439286 |

| DmTH | D. melanogaster | Tyrosine hydroxylase | AAF50648 |

| MmTH | Mus musculus | Tyrosine hydroxylase | NP033403 |

| HsTH | Homo sapiens | Tyrosine hydroxylase | NP000351 |

| DmPAH | D. melanogaster | Phenylalanine hydroxylase | CAA66798 |

| PxGTPCHI | P. xuthus | GTP cyclohydrolase I isoform B | AB220982 |

| BmGTPCHI | B. mori | GTP cyclohydrolase I isoform B | AB439288 |

| DmGTPCHI | D. melanogaster | GTP cyclohydrolase I | AY382624 |

| HsGTPCHI | H. sapiens | GTP cyclohydrolase I | AAB23164 |

| MmGTPCHI | M. musculus | GTP cyclohydrolase I | NP_032128 |

| DmEbony | D. melanogaster | Ebony | AAF55870 |

| AgEbony | Anopheles gambiae | Ebony | EAA03788 |

| AmEbony | Apis mellifera | Ebony | XP392634 |

| PxEbony | P. xuthus | Ebony | AB195255 |

| BmEbony | B. mori | Ebony | AB439000 |

| NRPS-COG1020 | Crocosphaera watsonii | Nonribosomal peptide synthetase modules and related proteins | ZP00177120 |

| NRPS-Pseudomonas | Pseudomonas syringae | Nonribosomal peptide synthetase, terminal component | AAO58141 |

| DmYellow-f2 | D. melanogaster | Yellow-f2 | NP_650247 |

| DmYellow-f | D. melanogaster | Yellow-f | NP_524335 |

| AedesDCE | Aedes aegypti | Dopachrome conversion enzyme | AAL85599 |

| BmYellow-fa | B. mori | Yellow-fa | DQ358080 |

| BmYellow-fb | B. mori | Yellow-fb | DQ358082 |

| BmYellow-f2 | B. mori | Yellow-f2 | DQ358084 |

| PxYellow | P. xuthus | Yellow | AB195254 |

| BmYellow | B. mori | Yellow | AB438999 |

| DmYellow | D. melanogaster | Yellow | AAF45497 |

| AgYellow | A. gambiae | Yellow | EAA12085 |

| DmYellow-b | D. melanogaster | Yellow-b | NP_523586 |

| DmYellow-c | D. melanogaster | Yellow-c | AAQ09899 |

| BmYellow-c | B. mori | Yellow-c | DQ358081 |

| DmYellow-h | D. melanogaster | Yellow-h | NP_651912 |

| DmYellow-g2 | D. melanogaster | Yellow-g2 | NP_647710 |

| DmYellow-g | D. melanogaster | Yellow-g | NP_523888 |

| DmYellow-e | D. melanogaster | Yellow-e | NP_524344 |

| BmYellow-b | B. mori | Yellow-b | DQ358083 |

| DmYellow-k | D. melanogaster | Yellow-k | NP_648772 |

| DmYellow-e3 | D. melanogaster | Yellow-e3 | NP_650288 |

| DmYellow-e2 | D. melanogaster | Yellow-e2 | NP_650289 |

| DmYellow-d2 | D. melanogaster | Yellow-d2 | NP_611788 |

| DmYellow-d | D. melanogaster | Yellow-d | NP_523820 |

| BmYellow-d | B. mori | Yellow-d | DQ358079 |

Reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction analyses:

Total RNA from several tissues (fat body, midgut, Malpighian tubules, epidermis, tracheae, and posterior silk gland) at day 3 of the fifth instar were extracted using TRI reagent (Sigma) and reverse transcribed with random primer (N6) and a first-strand cDNA synthesis kit (Amersham). The following primer sets were used for yellow: SO, 5′-TGAGTAAATAAAATGGCAGCGAAG-3′; S3, 5′-GAACAGAACAAGTCATGGAGATT-3′; ASO, 5′-TCTAGGAATTGAGAATTTGAACCA-3′; and AS2, 5′-GCGTTTTGGTCGATCAAGTTGAA-3′. And for ebony, the following primer sets were used: S4, 5′-TCCTCTGCTGGTAAACGGCA-3′; AS3, 5′-TCCAGCTCGGCTTTCTCGTA-3′; AS4, 5′-CGTGAACACGCCTCTGAAGC-3′; AS5, 5′-CGGAACCCTCCACGTACTCC-3′; and AS6, 5′-TGGTGAGATTCTCGATCTCG-3′. The PCR conditions used were 96° for 2 min followed by 30 (or 33) cycles of 96° for 15 sec, 50° (or 52°) for 15 sec, and 72° for 1 min. The reactions were kept at 72° for 1 min after the final cycle. The gene for Actin 3 was used as an internal control for normalization of equal sample loading.

Northern analysis:

Total RNA (10 μg) was separated on a formaldehyde–agarose (1%) gel and transferred to a Hybond-N nylon membrane (Amersham). Hybridization was performed at 42° for 18 hr in 50% formamide, 5× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 m sodium chloride and 0.15 m sodium citrate, pH 7.4), 10× Denhardt's solution (0.2% each of bovine serum albumin, Ficoll, and polyvinylpyrrolidone), 25 μg/ml sonicated salmon sperm DNA, 50 mm sodium phosphate (pH 7.0), and 32P-labeled DNA. Each DNA probe was labeled with [α-32P]dCTP using a BcaBEST labeling kit (TaKaRa, Otsu, Shiga, Japan). DNA probes were synthesized by PCR using the following primers: 5′-TGGGCTAGTCTCACTAGCATCAGC-3′ and 5′-AGCGGATGAAGTTTGTTTCGG-3′ for yellow (to test the developmental profile in epidermis), 5′-GAAGGTATCTTCGGCATCACG-3′ and 5′-ATACCGCAACGGCTTCAGAG-3′ for yellow (to test tissue specificity), and 5′-ACCGGCATTCCGAAAGGTGTGCGTT-3′ and 5′-TCACAGAAACGGTTCGCGCC-3′ for ebony. The membranes were washed twice at room temperature for 20 min in 2× SSC with 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS). The further washes were followed by 30 min at 65° successively in 2× SSC with 0.1% SDS and in 0.2× SSC with 0.1% SDS.

Whole-mount in situ hybridization:

Larval epidermis was dissected and then fixed immediately in 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (137 mm NaCl, 8.10 mm Na2HPO4, 2.68 mm KCl, and 1.47 mm KH2PO4, pH 7.4). Whole-mount in situ hybridization was performed as described by Futahashi and Fujiwara (2005, 2008b). RNA probes for yellow and ebony were prepared using a digoxigenin (DIG) RNA labeling kit (Roche Biochemicals, Mannheim, Germany) and primers were as described above in Northern analysis. Digoxigenin-labeled antisense RNA probes were used, and the color reaction was performed at room temperature in 100 mm Tris–HCl, 100 mm NaCl, and 50 mm MgCl2 (pH 9.5) containing 3.5 μl/ml 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-phosphate, 4-toluidine salt, and 4.5 μl/ml nitroblue tetrazolium chloride. Digoxigenin-labeled sense-strand probes were used as negative controls.

RESULTS

Mapping of the melanin-synthesis genes:

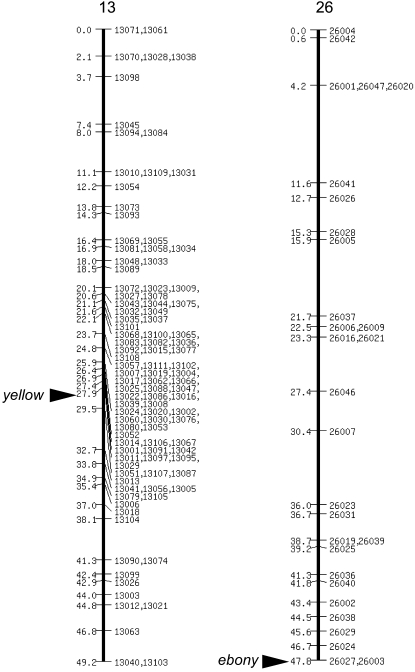

We focused on the five melanin-synthesis (or related) genes, tyrosine hydroxylase (TH), dopa decarboxylase (DDC), guanosine triphosphate cyclohydrolase I (GTPCH I), yellow, and ebony, all of which are associated with stage-specific larval body markings in Papilio xuthus (Futahashi and Fujiwara 2005, 2006, 2007, 2008a). In B. mori, DDC (Hwang et al. 2003) has been reported in the full-length cDNA, and both GTPCH I (Kato et al. 2006) and yellow (Xia et al. 2006) have been reported in a partial sequence. We cloned melanin-synthesis genes using genomic information, reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT–PCR), and RACE. We obtained the full-length cDNA sequences of B. mori TH (GenBank accession no. AB439286), yellow (AB438999), and ebony (AB439000). We found two isoforms of the GTPCH I gene (AB439287 and AB439288), which encode proteins of distinct N termini as with P. xuthus (Futahashi and Fujiwara 2006). Phylogenetic analysis of these genes indicated that they cluster with other insect homologs and thus represent the TH, GTPCH I, yellow, and ebony orthologs in B. mori (Figure 2, Table 1). Although Yellow proteins form a large protein family (Albert and Klaudiny 2004), phylogenetic analysis indicated that B. mori Yellow clusters with other insect yellow homologs and thus represents the genuine yellow ortholog of B. mori (Figure 2). To determine the chromosomal location of the five melanin-synthesis (or related) genes, we performed genetic linkage analyses using 190 BC1 individuals from a single pair mating between a p50T female and an F1 male (p50T female × C108T male; Yamamoto et al. 2006, 2008). We constructed SNP markers of these genes (supplemental Figure 1), and the SNP markers segregated into 1 of 28 linkage groups as previously reported (Yamamoto et al. 2006, 2008). We could not obtain a clear result for the GTPCH I gene, perhaps because of the duplication of SNP markers. Except for GTPCH I, each of the four melanin-synthesis (or related) genes was located on a distinct linkage group (Figure 3, Table 2). Among them, yellow (27.9 cM of the SNP linkage group 13) and ebony (the end of the SNP linkage group 26) were located near the two color mutants, ch (9.6 cM of the phenotypic linkage group 13) and so (the end of the phenotypic linkage group 26), respectively (Figure 3, Table 2). Although the number of the SNP linkage group is the same as that of the phenotypic linkage group, the orientation of the SNP linkage group is not always the same as that of the phenotypic linkage group. We therefore analyzed the relationships by linkage analyses between the wild-type and mutant strains.

Figure 2.—

Neighbor-joining tree of TH, GTPCH I, Yellow, Ebony, and related genes based on their amino acid sequences. The numbers at the tree edges represent the bootstrap values. The scale bars indicate the evolutionary distance between the groups. Boxes indicate the B. mori orthologs. The sequences used to create the diagram are listed in Table 1.

Figure 3.—

Linkage map between yellow and ebony and linkage groups 13 and 26, respectively. On the chromosome maps, loci are labeled by position in centimorgans (left) and locus name (right). Linkage maps are the same as in Yamamoto et al. (2008). Segregation patterns of single-nucleotide polymorphism were surveyed using 190 BC1 individuals from a single pair mating between a p50T female and an F1 male (p50T female × C108T male) as previously reported (Yamamoto et al. 2006). Chromosomal positions of yellow and ebony genes are indicated by arrowheads.

TABLE 2.

Chromosomal mapping of five genes involved in melanin-synthesis pathway

| Gene | Chromosome | Position (cM) |

|---|---|---|

| TH | 1 | 19.0 |

| DDC | 4 | 29.3 |

| yellow | 13 | 27.9 |

| ebony | 26 | 49.2 |

Positions in each chromosome are as referred to in Yamamoto et al. (2008).

Linkage analysis of the yellow gene and the ch locus:

To determine the linkage between the ch locus and the yellow gene, we performed an F2 linkage analysis based on an SNP of the yellow gene. The first base of intron 3 of the yellow gene of the wild-type p50T strain was guanine, while that of the chk12 strain was adenine (this substitution caused nonsense mutations; see below). The coloration of neonate larvae of F2 individuals was either black or reddish brown (see Figure 1B). By analyzing 179 individuals obtained from an F2 intercross (heterozygous F1 females mated to F1 heterozygous males), we found that all 93 reddish-brown specimens (chk12/chk12) were A/A homozygous, while all 86 black (+/+, chk12/+) F2 larvae were G/G homozygous or A/G heterozygous (Table 3). These results indicate that the yellow gene is tightly linked to the ch locus (recombination value <0.56%). Because the 1-cM distance on the Bombyx classical genetic map is estimated to be ∼300–600 kb (Sato et al. 2008), the region of linkage in the F2 analysis is expected to be ∼170–340 kb.

TABLE 3.

Linkage analysis of the yellow gene

| SNP of yellow gene

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Phenotype (genotype) | G/G | A/G | A/A |

| Black (+/+, ch/+) | 27 | 59 | 0 |

| Red (ch/ch) | 0 | 0 | 93 |

Single nucleotide polymorphism analysis was performed on 179 individuals obtained from an F2 intercross (heterozygous F1 females mated to F1 heterozygous males). The first base of the third intron of yellow of wild type (p50T strain) was guanine while that of chk12 was adenine.

Linkage analysis of the ebony gene and the so locus:

To determine the linkage between the so locus and the ebony gene, we performed an F2 linkage analysis based on the length of ebony gene PCR fragments. The lengths of the amplified fragments of the two primers designed from the 10th intron of the ebony gene were 1.3 kb in wild-type p50T and 0.8 kb in mutant soi41. The pupal coloration of F2 individuals was either black (so mutant) or light brown (wild type; see Figure 1C). By analyzing 191 individuals obtained from a backcross (soi41 mutant female mated to an F1 heterozygous male), we found that all 97 black pupae (soi41/soi41) had only 0.8-kb PCR fragments, while all 94 light-brown pupae (soi41/+) had both 1.3- and 0.8-kb PCR fragments (Table 4). These results indicate that the ebony gene is tightly linked to the so locus (with the recombination value <0.52%, the region of linkage in the backcross analysis is expected to be ∼150–300 kb.)

TABLE 4.

Linkage analysis of the ebony gene

| PCR fragment of ebony gene

|

||

|---|---|---|

| Phenotype (genotype) | 1.3 kb and 0.8 kb | 0.8 kb only |

| Brown (so/+) | 94 | 0 |

| Black (so/so) | 0 | 97 |

PCR analysis was performed on 191 individuals obtained from a backcross (soi41 mutant female mated to an F1 heterozygous male).

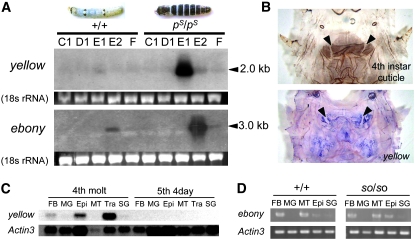

Expression analysis of yellow and ebony genes:

In the swallowtail butterfly, P. xuthus, yellow expression coincided with larval black markings in the middle of the molting period (Futahashi and Fujiwara 2007), whereas ebony expression coincided with larval reddish-brown markings in the latter part of the molting period (Futahashi and Fujiwara 2005). To determine the correlation between Bombyx larval coloration and yellow and/or ebony genes, we investigated the temporal expression patterns of yellow and ebony mRNA in the epidermis by Northern hybridization. On the basis of the visible characteristics, 10 morphological larval stages [A, B, C1, C2, D1, D2, D3, E1, E2 (A–E, fourth instar larval stage), and F (fifth instar larval stage)] could be distinguished and were referred to as the “spiracle index.” D1 is a stage when head capsule slippage occurs, and ecdysteroid titer declines during E1 and E2 stages (Kiguchi and Agui 1981). In the wild-type strain, faint yellow expression was detected at E1 and weak ebony expression was detected at E2 (Figure 4A, left). To analyze yellow expression more clearly, we performed Northern hybridization using the pS (striped) strain, which has black stripes on each segment (Figure 4A; Fujiwara et al. 1991). In the pS strain, yellow mRNA was strongly expressed at E1, and ebony mRNA was strongly expressed at E2 (Figure 4A, right). Whole-mount in situ hybridization showed that yellow expression correlated strongly with the presumptive black markings (Figure 4B) and was not detected in the white striped region (arrowheads in Figure 4B), similar to P. xuthus larvae (Futahashi and Fujiwara 2007), whereas ebony expression was broadly detected (data not shown). We next analyzed the tissue specificity of yellow and ebony mRNA. In addition to the epidermis, yellow transcripts were detected in fat body and tracheae during the molting period, but not during the intermolt period (Figure 4C). By RT–PCR analysis, ebony transcripts were also detected in fat body and Malpighian tubules even during the intermolt period (Figure 4D). We also investigated numerous Bombyx EST libraries (Mita et al. 2003; Okamoto et al. 2008) and found that yellow transcripts were found in compound eyes, epidermis, and wing disc libraries, while ebony transcripts were not found in any library (data not shown).

Figure 4.—

(A) Northern analyses of yellow and ebony in epidermis during the fourth molting period in wild-type (+p) and striped (pS) strain larvae. Dorsal view of each strain of larvae is shown above. Ethidium bromide staining of rRNA is shown as loading control. The molting stage (C1, D1, E1, E2, and F) was determined on the basis of the spiracle index (Kiguchi and Agui 1981). Arrowheads indicate the positive signal. Expression of both yellow and ebony are stronger in the pS strain than in the +p strain. (B) Spatial expression of yellow mRNA in the pS strain at the thoracic segments. The cuticular pigmentation pattern of the fourth instar larva is shown above. yellow expression coincided with the black regions and was not detected at the white striped region (arrowheads). (C) Northern analysis of yellow mRNA from several tissues of wild type (p50T strain) at fourth molt or mid-fifth larvae. FB, fat body; MG, midgut; Epi, epidermis; MT, Malpighian tubules; Tra, tracheae; SG, silk gland. Actin3 is shown as a control. (D) RT–PCR analysis of the ebony mRNA in tissues in the V3 (day 3, fifth instar) larvae of wild type (p50T strain) and homozygous so strain (soi41/soi41). FB, fat body; MG, midgut; MT, Malpighian tubules; Epi, epidermis; SG, silk gland. Actin 3 is shown as control.

Mutations of the yellow gene in the ch mutant:

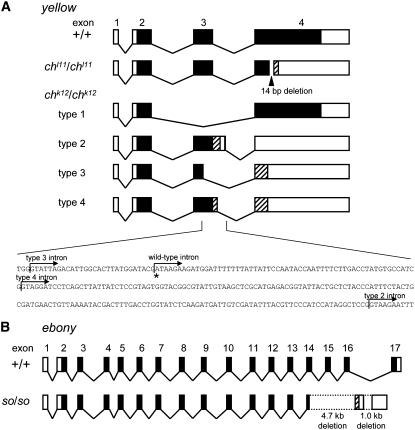

We determined the complete cDNA sequences of the yellow genes amplified by RT–PCR and RACE from the wild-type p50T strain and two alleles of ch mutants, chk12 and chl11. In the chl11 strain, we found a 14-bp deletion within exon 4. This deletion causes a frameshift within exon 4 and a premature TAA stop codon (Figure 5A, AB455226). We also confirmed this deletion using genomic DNA in the chl11 strain (AB455232). By RT–PCR, multiple bands were detected in the chk12 strain (supplemental Figure 2). We further identified a cDNA sequence after subcloning and found that four cDNAs were produced in the chk12 strain (Figure 5A, AB455227–AB455230). All of these cDNAs had aberrant exon 3's (Figure 5A). Type 1 cDNA was spliced from exon 2 to exon 4 and did not have exon 3 (the stop codon position is identical to that of the wild type). Type 2 cDNA had a 167-bp-longer exon 3 than the wild type, which caused a premature TGA stop codon in exon 3. Type 3 cDNA was spliced before normal intron 3 and had a 29-bp-shorter exon 3 than the wild type, which caused a premature TGA stop codon in exon 4. Type 4 cDNA had an 88-bp-longer exon 3 than the wild type, which also caused a premature TGA stop codon in exon 4. To clarify the cause of an abnormal exon 3, we also investigated the genomic sequence of the chk12 strain (AB455233) and found that the first base of intron 3 is substituted from G to A in chk12 (Figure 5A, bottom, denoted by asterisk), which violated the GT/AG rule. This disturbance possibly causes inaccurate splicing (new splice junctions were canonical splice junctions as shown in Figure 5A), which results in multiple cDNA production in chk12. These results demonstrate that the two alleles chk12 and chl11 encode nonsense-mutated yellow genes (Figure 5A).

Figure 5.—

(A) yellow cDNA comparison among wild-type and ch mutants. yellow cDNA of chl11 has a 14-bp deletion in the fourth exon. In chk12, the splicing site of intron 3 is mutated (below), and four types cDNA were cloned for yellow. Asterisk indicates the mutation site at the first base of intron 3. Arrows indicate splicing sites of intron 3 in chk12 strain (types 2, 3, 4). Solid boxes, open reading frames; open boxes, untranslated regions; striped boxes, aberrant open reading frames; diagonal lines, introns. (B) ebony cDNA comparison between wild type and so mutant. The large deletion causes a fatal change of the C-terminal amino acid sequence of the Ebony homolog protein. Solid boxes, open reading frames; open boxes untranslated regions; striped box, aberrant open reading frame; diagonal lines, introns; dotted lines, deleted region.

To provide information on the function of Yellow proteins, we compared Yellow amino acid sequences in B. mori, P. xuthus, and D. melanogaster. Amino acid sequences of Yellow proteins were highly conserved among these three species in the major royal jelly protein conserved motif (Yellow box in supplemental Figure 3) and the N-terminal region except for the signal peptide sequence (dotted line in supplemental Figure 3). All mutant proteins disrupted a large part of a major royal jelly protein conserved motif (supplemental Figure 3). Yellow had two potential N-glycosylation sites (Geyer et al. 1986; Drapeau 2003) in all three species, and mutated Yellow proteins (except for type 1 of chk12 mutant) lacked both of these sites (types 2, 3, and 4 of the chk12 mutant) or one of these sites (chl11 mutant). These results suggest that a major royal jelly protein conserved motif including two potential N-glycosylation sites is critical for Yellow function.

Mutations of the ebony gene in the so mutant:

We determined the complete cDNA sequences of the ebony genes amplified by RT–PCR and RACE from the wild-type p50T and soi41 strains. In soi41 strains, we found large deletions in the C-terminal regions of the ebony ORF (Figure 5B, AB455231). By RT–PCR, we confirmed the same deletion of ebony in the other alleles of soi10 mutants (supplemental Figure 4) and that the ebony sequence of soi10 strain is identical to that of soi41, suggesting that these two strains were derived from the same origin. The deletion of 4.7 kb from the middle part of exon 14 to the 5′ region of intron 16 and that of 1 kb in the middle portion of intron 16 produced an aberrant chimeric structure of exon 14 and an abnormal poly(A) site in the soi41 mutant (Figure 5B). This aberration caused a fatal change of the C-terminal sequence of the Ebony protein (supplemental Figure 5). We also confirmed this deletion using genomic DNA in soi41 (data not shown). These results showed that the functional Ebony protein was not expressed from the so alleles.

To provide information on the function of Ebony proteins, we compared Ebony amino acid sequences in B. mori, P. xuthus, and D. melanogaster. Ebony protein has a sequence similarity with nonribosomal peptide synthetase, and several consensus core sequences (A1–A10 and T) have been reported (Richardt et al. 2003). Amino acid sequences of these conserved motifs were highly conserved among these three species except for A1 core sequence (green bracket in supplemental Figure 5). We found that amino acid sequences of the C-terminal region (putative amine-selecting domain, green arrow in supplemental Figure 5; Richardt et al. 2003) were also conserved among three insect species and that mutated Ebony proteins lacked a large part of this domain (red arrow in supplemental Figure 5), suggesting that the C-terminal region is critical for Ebony function.

DISCUSSION

Several lines of evidence strongly suggest that yellow and ebony are responsible for the Bombyx color pattern mutants, ch and so, respectively. First, yellow and ebony perfectly cosegregated with the ch and so loci, respectively (Figure 3). Second, severe defects within the yellow ORF existed in the ch mutant, and large deletions within the ebony ORF existed in the so mutant. In both cases, nonsense-mutated proteins were produced (Figure 5; supplemental Figures 3 and 5). Third, expression timing of both genes was associated with the molting period when cuticular pigmentation occurs, and distribution of yellow mRNA coincided with the black markings (Figure 4). To our knowledge, this is the first report of melanin-synthesis genes being responsible for color pattern mutants in Lepidoptera. Our results suggest a conserved role of Yellow and Ebony proteins and the potential involvement of both genes in the black color pattern evolution in Lepidoptera.

Yellow function of black color pattern in insects:

In D. melanogaster, Yellow protein is necessary for normal pigmentation and the distribution of Yellow prefigures adult pigmentation patterns in accordance with species-specific black color pattern (Wittkopp et al. 2002a,b; Gompel et al. 2005). Mutations in the yellow gene produce an altered form of melanin, which results in the light “Yellow” coloration instead of the normal black coloration (Geyer et al. 1986; Wright 1987; Wittkopp et al. 2002a). Yellow protein may act in the melanin-synthesis pathway downstream from dopa and/or dopamine (Gibert et al. 2007), although the precise function of Yellow remains unclear (Drapeau 2003; Gibert et al. 2007).

Other than Drosophila, Yellow protein is thought to be involved in larval pigmentation patterns in P. xuthus because yellow expression coincides with the stage-specific black markings (Futahashi and Fujiwara 2007). Together with our results, yellow determines the black pigmentation pattern among insects other than Drosophila and may be associated with black color pattern evolution. In P. xuthus larvae, yellow expression is restricted to the middle stage of the larval molting period, and topical application of ecdysteroid promotes yellow expression (Futahashi and Fujiwara 2007). In B. mori, yellow expression was also restricted to the middle stage of the larval molting period (Figure 4, A and C), suggesting that regulation of ecdysteroid on yellow expression is conserved among lepidopteran species. Because black pigmentation is often regulated by ecdysteroid titer in Lepidoptera, yellow is a candidate for connecting ecdysteroid signaling with black pigmentation, like dopa decarboxylase (Hiruma et al. 1995; Futahashi and Fujiwara 2007).

Unlike D. melanogaster, yellow transcripts were found in various tissues, including the compound eye. The coloration of adult compound eye was normal in mutant strains, suggesting that yellow is not involved in eye coloration in the silkworm. Because the cDNA library for compound eyes was constructed using mixed stages from fifth instar to pupal (Mita et al. 2003), one possibility is that yellow is associated with pupal cuticular coloration at compound eyes.

Yellow proteins and Major royal jelly proteins (apalbumin) form a large protein family (Albert and Klaudiny 2004). In D. melanogaster, 14 Yellow protein genes have been reported (Drapeau 2001). The yellow-f and yellow-f2 genes have dopachrome-conversion enzyme activity that likely plays an important role during melanin biosynthesis in D. melanogaster (Han et al. 2002). In B. mori, seven Yellow protein genes have been reported (Xia et al. 2006). Other yellow genes of B. mori may also function in pigment synthesis as Drosophila yellow-f does and may be responsible for other color pattern mutants.

Ebony function of color pattern in insects:

Ebony combines β-alanine with dopamine to form N-β-alanyldopamine (NBAD), which is the precursor for a light-colored pigment found in the cuticles of many insect species (Fukushi and Seki 1965; Wright 1987). In the adult abdominal pigmentation of D. melanogaster, Ebony expression is detected uniformly and masks melanization (Wittkopp et al. 2002a). The difference in expression level of ebony is responsible for the variation in thoracic trident pigmentation between the two representative lines in D. melanogaster (Takahashi et al. 2007), and DNA polymorphism of ebony has a clear association with the level of abdominal pigmentation (Pool and Aquadro 2007). Differences in the expression levels of Ebony protein also correlate with the intensity of adult pigmentation between Drosophila americana and Drosophila novamexicana (Wittkopp et al. 2003). In the ebony mutant of D. melanogaster, dopamine cannot be converted to NBAD, but instead follows an alternate pathway, producing a black pigment. The adult body color of the ebony mutant is therefore very dark (Fukushi 1967; Wright 1987; Wittkopp et al. 2002a).

Other insect species also require β-alanine for cuticle tanning. Notably, Fukushi and Seki (1965) demonstrated that β-alanine was found in the pupal sheaths of wild strains of Bombyx, but not in a so mutant of B. mori, as in an ebony mutant of D. melanogaster (Fukushi 1967). The similarity of pupal amino acid composition also supports our results; we proposed that Bombyx so is the ortholog of Drosophila ebony (Figure 2). Black mutants of the housefly, Musca domestica, also lack β-alanine in their pupal sheaths (Fukushi and Seki 1965). The cuticle of the red flour beetle, Tribolium castaneum, is normally a rust-red color as a result of low levels of dopamine combined with high levels of NBAD. A black mutant strain has much higher levels of dopamine and greatly reduced amounts of β-alanine and NBAD (Kramer et al. 1984). Ebony may be responsible for black mutants among insects.

In Lepidoptera, the Ebony protein is involved in the production of yellow papiliochrome in Papilio glaucus adult wing (Koch et al. 2000) and reddish-brown pigments in P. xuthus larval body markings (Futahashi and Fujiwara 2005). The activity of Ebony is concerned with light pigmentation in both cases. In B. mori larvae, however, larval cuticle is mainly transparent, and Ebony expression was detected uniformly, suggesting that Ebony masks melanization as in Drosophila (Wittkopp et al. 2002a).

Other color pattern mutants in Bombyx:

There are many spontaneous color pattern mutants (mainly in larvae) in B. mori (Banno et al. 2005). Bombyx color pattern mutants are good examples of how similar phenotypes are caused by different loci. Similar to so mutants, another mutant, black pupa (bp; 40.3 cM of linkage group 11), produces black pupa (Hashiguchi et al. 1965), although β-alanine is found in the pupal sheaths (Fukushi and Seki 1965). Other than the ch mutant, reddish-brown pigmentation of neonate larvae is also characteristic of four other mutant strains: sex-linked chocolate (sch), Dominant chocolate (Ia), chocolate-2 (ch-2), and maternal chocolate (cm). All of these loci have been mapped on the Bombyx linkage group: sch—21.5 cM of linkage group 1; Ia—22.1 cM of linkage group 9; ch-2—0.0 cM of linkage group 18; and cm—41.9 cM of linkage group 20 (Banno et al. 2005). We found that the TH gene, the first enzyme of the melanin-synthesis pathway, was located to 19.0 cM of linkage group 1 (Table 2), which is near the sch locus. Further studies are needed to determine whether TH is associated with the sch mutant.

Notably, adult color patterns are affected only slightly in both ch and so mutants. In many cases, adult and larval color patterns are regulated independently (Banno et al. 2005). In two mutants, Black moth (Bm; 0.0 cM of linkage group 17) and melanism (mln; 41.5 cM of linkage group 18), the coloration of adult wings is overall black, but the Bm larval coloration is normal. The responsible genes of these two mutants may be associated with adult wing color variation. By mating ch and/or so mutants with other mutant strains, we can see how melanin-synthesis enzymes play a role in color pattern formation and how they interact with other color pattern genes. Recently, positional cloning of several mutants has been completed in B. mori (Ito et al. 2008; Sato et al. 2008). Exhaustive identification of these color pattern mutants will shed light on the mechanisms of color pattern evolution in Lepidoptera.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan to H.F., T.S., and T.D., National BioResource Project to Y.B., the Program for Promotion of Basic Research Activities for Innovative Bioscience to H.F. R.F. is the recipient of a Research Fellowship of Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) for Young Scientists. Y.M. is the recipient of a JSPS Postdoctoral Fellowship Program for Foreign Researchers.

References

- Albert, S., and J. Klaudiny, 2004. The MRJP/YELLOW protein family of Apis mellifera: identification of new members in the EST library. J. Insect Physiol. 50 51–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul, S. F., T. L. Madden and A. A. Schaffer, 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25 3389–3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banno, Y., Y. Kawaguchi, I. Shokyu and H. Doira, 1989. Linkage studies of Bombyx mori: discovery of the twenty-sixth linkage group, sooty and non-molting of Ishiko. J. Seric. Sci. Jpn. 58 234–239. [Google Scholar]

- Banno, Y., H. Fujii, Y. Kawaguchi, K. Yamamoto, K. Nishikawa et al., 2005. A Guide to the Silkworm Mutants: 2005 Gene Name and Gene Symbol. Kyusyu University, Fukuoka, Japan.

- Beldade, P., P. M. Brakefield and A. D. Long, 2002. Contribution of Distal-less to quantitative variation in butterfly eyespots. Nature 415 315–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beldade, P., W. O. McMillan and A. Papanicolaou, 2008. Butterfly genomics eclosing. Heredity 100 150–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brakefield, P. M., J. Gates, D. N. Keys, F. Kesbeke, P. J. Wijngaarden et al., 1996. Development, plasticity and evolution of butterfly eyespot patterns. Nature 384 236–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunetti, C. R., J. E. Selegue, A. Monteiro, V. French, P. M. Brakefield et al., 2001. The generation and diversification of butterfly eyespot color patterns. Curr. Biol. 11 1578–1585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, S. B., J. Gates, D. N. Keys, S. W. Paddock, G. E. Panganiban et al., 1994. Pattern formation and eyespot determination in butterfly wings. Science 265 109–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark, R., S. M. Brown, S. C. Collins, C. D. Jiggins, D. G. Heckel et al., 2008. Colour pattern specification in the Mocker swallowtail Papilio dardanus: the transcription factor invected is a candidate for the mimicry locus H. Proc. Biol. Sci. 275 1181–1188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drapeau, M. D., 2001. The family of yellow-related Drosophila melanogaster proteins. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 281 611–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drapeau, M. D., 2003. A novel hypothesis on the biochemical role of the Drosophila Yellow protein. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 311 1–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujiwara, H., O. Ninaki, M. Kobayashi, J. Kusuda and H. Maekawa, 1991. Chromosomal fragment responsible for genetic mosaicism in larval body marking of the silkworm, Bombyx mori. Genet. Res. 57 11–16. [Google Scholar]

- Fukushi, Y., 1967. Genetic and biochemical studies on amino acid compositions and color manifestation in pupal sheaths of insects. Jpn. J. Genet. 42 11–21. [Google Scholar]

- Fukushi, Y., and T. Seki, 1965. Differences in amino acid compositions of pupal sheaths between wild and black pupa strains in some species of insects. Jpn. J. Genet. 40 203–208. [Google Scholar]

- Futahashi, R., and H. Fujiwara, 2005. Melanin-synthesis enzymes coregulate stage-specific larval cuticular markings in the swallowtail butterfly, Papilio xuthus. Dev. Genes Evol. 215 519–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Futahashi, R., and H. Fujiwara, 2006. Expression of one isoform of GTP cyclohydrolase I coincides with the larval black markings of the swallowtail butterfly, Papilio xuthus. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 36 63–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Futahashi, R., and H. Fujiwara, 2007. Regulation of 20-hydroxyecdysone on the larval pigmentation and the expression of melanin synthesis enzymes and yellow gene of the swallowtail butterfly, Papilio xuthus. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 37 855–864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Futahashi, R., and H. Fujiwara, 2008. a Juvenile hormone regulates butterfly larval pattern switches. Science 319 1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Futahashi, R., and H. Fujiwara, 2008. b Identification of stage-specific larval camouflage associated genes in the swallowtail butterfly, Papilio xuthus. Dev. Genes Evol. 218 491–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geyer, P. K., C. Spana and V. G. Corces, 1986. On the molecular mechanism of gypsy-induced mutations at the yellow locus of Drosophila melanogaster. EMBO J. 5 2657–2662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibert, J. M., F. Peronnet and C. Schlötterer, 2007. Phenotypic plasticity in Drosophila pigmentation caused by temperature sensitivity of a chromatin regulator network. PLoS Genet. 3 e30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gompel, N., B. Prud'homme, P. J. Wittkopp, V. A. Kassner and S. B. Carroll, 2005. Change caught on the wing: cis-regulatory evolution and the origin of pigment patterns in Drosophila. Nature 433 481–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han, Q., J. Fang, H. Ding, J. K. Johnson, B. M. Christensen et al., 2002. Identification of Drosophila melanogaster yellow-f and yellow-f2 proteins as dopachrome-conversion enzymes. Biochem. J. 368 333–340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashiguchi, T., N. Yoshitake and N. Takahashi, 1965. Hormone determining the black pupal colour in the silkworm, Bombyx mori L. Nature 206 215. [Google Scholar]

- Hiruma, K., M. S. Carter and L. M. Riddiford, 1995. Characterization of the dopa decarboxylase gene of Manduca sexta and its suppression by 20-hydroxyecdysone. Dev. Biol. 169 195–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, J. S., S. W. Kang, T. W. Goo, E. Y. Yun, J. S. Lee et al., 2003. cDNA cloning and mRNA expression of L-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine decarboxylase gene homologue from the silkworm, Bombyx mori. Biotechnol. Lett. 25 997–1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito, K., K. Kidokoro, H. Sezutsu, J. Nohata, K. Yamamoto et al., 2008. Deletion of a gene encoding an amino acid transporter in the midgut membrane causes resistance to a Bombyx parvo-like virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105 7523–7527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato, T., H. Sawada, T. Yamamoto, K. Mase and M. Nakagoshi, 2006. Pigment pattern formation in the quail mutant of the silkworm, Bombyx mori: parallel increase of pteridine biosynthesis and pigmentation of melanin and ommochromes. Pigment Cell Res. 19 337–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiguchi, K., and N. Agui, 1981. Ecdysteroid levels and developmental events during larval moulting in the silk worm, Bombyx mori. J. Insect Physiol. 27 805–812. [Google Scholar]

- Koch, P. B., B. Behnecke and R. H. ffrench-Constant, 2000. The molecular basis of melanism and mimicry in a swallowtail butterfly. Curr. Biol. 10 591–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosambi, D. D., 1944. The estimation of map distances from recombination values. Ann. Eugen. 12 172–175. [Google Scholar]

- Kramer, K. J., T. D. Morgan, T. L. Hopkins, C. R. Roseland, Y. Aso et al., 1984. Catecholamines and beta-alanine in the red flour beetle, Tribolium castaneum. Insect Biochem. 14 293–298. [Google Scholar]

- Kronforst, M. R., L. G. Young, D. D. Kapan, C. McNeely, R. J. O'Neill et al., 2006. Linkage of butterfly mate preference and wing color preference cue at the genomic location of wingless. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103 6575–6580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lander, E. S., P. Green, J. Abrahamson, A. Barlow, M. J. Daly et al., 1987. MAPMAKER: an interactive computer package for constructing primary genetic linkage maps of experimental and natural populations. Genomics 1 174–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mita, K., M. Morimyo, K. Okano, Y. Koike, J. Nohata et al., 2003. The construction of an EST database for Bombyx mori and its application. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100 14121–14126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mita, K., M. Kasahara, S. Sasaki, Y. Nagayasu, T. Yamada et al., 2004. The genome sequence of silkworm, Bombyx mori. DNA Res. 11 27–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro, A., G. Glaser, S. Stockslager, N. Glansdorp and D.Ramos, 2006. Comparative insights into questions of lepidopteran wing pattern homology. BMC Dev. Biol. 6 52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto, S., R. Futahashi, T. Kojima, K. Mita and H. Fujiwara, 2008. A catalogue of epidermal genes: genes expressed in the epidermis during larval molt of the silkworm Bombyx mori. BMC Genomics 9 396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pool, J. E., and C. F. Aquadro, 2007. The genetic basis of adaptive pigmentation variation in Drosophila melanogaster. Mol. Ecol. 16 2844–2851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed, R. D., and M. S. Serfas, 2004. Butterfly wing pattern evolution is associated with changes in a Notch/Distal-less temporal pattern formation process. Curr. Biol. 14 1159–1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardt, A., T. Kemme, S. Wagner, D. Schwarzer, M. A. Marahiel et al., 2003. Ebony, a novel nonribosomal peptide synthetase for beta-alanine conjugation with biogenic amines in Drosophila. J. Biol. Chem. 278 41160–41166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozen, S., and H. Skaletsky, 2000. Primer3 on the WWW for general users and for biologist programmers, pp. 365–386 in Bioinformatics Methods and Protocols: Methods in Molecular Biology, edited by S. Misener and S. A. Krawetz. Humana Press, Totowa, NJ. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sato, K., T. M. Matsunaga, R. Futahashi, T. Kojima, K. Mita et al., 2008. Positional cloning of a Bombyx wingless locus flugellos (fl) reveals a crucial role for fringe that is specific for wing morphogenesis. Genetics 179 875–885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stajich, J. E., D. Block, K. Boulez, S. E. Brenner, S. A. Chervitz et al., 2002. The Bioperl toolkit: Perl modules for the life sciences. Genome Res. 12 1611–1618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki, K., 1942. A new mutant in the silkworm, “cray-fish pupa” and its linkage. Jpn. J. Genet. 18 26–33. [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi, A., K. Takahashi, R. Ueda and T. Takano-Shimizu, 2007. Natural variation of ebony gene controlling thoracic pigmentation in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 177 1233–1237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura, K., J. Dudley, M. Nei and S. Kumar, 2007. MEGA4: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 24 1596–1599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka, Y., 1924. New research on the heredity of cocoon color in silkworms. Sangyo-shinpo 367 92–96. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, J. D., T. J. Gibson, F. Plewniak, F. Jeanmougin and D. G. Higgins, 1997. The CLUSTAL_X windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 25 4876–4882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toyama, K., 1909. Studies on the hybridology of insects. II. A sport of the silk-worm, Bombyx mori L., and its hereditary behavior. J. College Agric. (Tokyo Imperial University) 2 85–103. [Google Scholar]

- Wittkopp, P. J., J. R. True and S. B. Carroll, 2002. a Reciprocal functions of the Drosophila yellow and ebony proteins in the development and evolution of pigment patterns. Development 129 1849–1858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittkopp, P. J., K. Vaccaro and S. B. Carroll, 2002. b Evolution of yellow gene regulation and pigmentation in Drosophila. Curr. Biol. 12 1547–1556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittkopp, P. J., B. L. Williams, J. E. Selegue and S. B. Carroll, 2003. Drosophila pigmentation evolution: divergent genotypes underlying convergent phenotypes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100 1808–1813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright, T. R. F., 1987. The genetics of biogenic amine metabolism, sclerotization, and melanization in Drosophila melanogaster. Adv. Genet. 24 127–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia, Q., Z. Zhou, C. Lu, D. Cheng, F. Dai et al., 2004. A draft sequence for the genome of the domesticated silkworm (Bombyx mori). Science 306 1937–1940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia, A. H., Q. X. Zhou, L. L. Yu, W. G. Li, Y. Z. Yi et al., 2006. Identification and analysis of YELLOW protein family genes in the silkworm, Bombyx mori. BMC Genomics 7 195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto, K., J. Narukawa, K. Kadono-Okuda, J. Nohata, M. Sasanuma et al., 2006. Construction of a single nucleotide polymorphism linkage map for the silkworm, Bombyx mori, based on bacterial artificial chromosome end sequences. Genetics 173 151–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto, K., J. Nohata, K. Kadono-Okuda, J. Narukawa, M. Sasanuma et al., 2008. A BAC-based integrated linkage map of the silkworm Bombyx mori. Genome Biol. 9 R21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]