Abstract

In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Cdc13 binds telomeric DNA to recruit telomerase and to “cap” chromosome ends. In temperature-sensitive cdc13-1 mutants telomeric DNA is degraded and cell-cycle progression is inhibited. To identify novel proteins and pathways that cap telomeres, or that respond to uncapped telomeres, we combined cdc13-1 with the yeast gene deletion collection and used high-throughput spot-test assays to measure growth. We identified 369 gene deletions, in eight different phenotypic classes, that reproducibly demonstrated subtle genetic interactions with the cdc13-1 mutation. As expected, we identified DNA damage checkpoint, nonsense-mediated decay and telomerase components in our screen. However, we also identified genes affecting casein kinase II activity, cell polarity, mRNA degradation, mitochondrial function, phosphate transport, iron transport, protein degradation, and other functions. We also identified a number of genes of previously unknown function that we term RTC, for restriction of telomere capping, or MTC, for maintenance of telomere capping. It seems likely that many of the newly identified pathways/processes that affect growth of budding yeast cdc13-1 mutants will play evolutionarily conserved roles at telomeres. The high-throughput spot-testing approach that we describe is generally applicable and could aid in understanding other aspects of eukaryotic cell biology.

LINEAR chromosomes are a feature of all eukaryotes. The single-celled model eukaryote Saccharomyces cerevisiae, for example, has 16 linear chromosomes with ends that are, in principle, no different from double-stranded breaks elsewhere in the genome. However, whereas S. cerevisiae cells can tolerate 32 or more chromosome ends throughout its cell cycle, a single double-stranded DNA break (DSB) elsewhere in the genome elicits a swift and precise response (Sandell and Zakian 1993). This response includes checkpoint activation, which leads to cell-cycle arrest prior to repair of the break. The difference between DSBs and chromsosome ends, then, comes down to specific nucleoprotein complexes that occupy the ends of chromosomes to form a structure referred to as a telomere (Longhese 2008).

A further issue at the ends of chromosomes is the inability of semi-conservative DNA replication to reach the very ends of linear double-stranded DNA molecules—the “end replication problem” (Olovnikov 1973). Telomerase (Greider and Blackburn 1985), a telomere-specific reverse-transcriptase complex, solves this problem by adding G-rich repeat sequences to the 3′-end of chromosomes, using a bound RNA molecule as a template. As a result, eukaryotic chromosomes have long stretches of TG repeats at their ends. These sequences serve as a binding platform for proteins involved in end protection and telomerase recruitment.

The length of telomere repeat sequences in growing and dividing cells depends on a balance between shortening, due to the end replication problem, and lengthening, due to the actions of telomerase. Should the length of telomere repeat sequences fall below a critical level, budding yeast and mammalian cells stop dividing in a checkpoint-dependent process referred to as senescence (Reaper et al. 2004). In rare instances, cells can evade this fate by employing telomerase-independent, recombination-based pathways for maintaining a functional number of TG repeats at the ends of chromosomes. In cells that lack telomerase—as is the case for the majority of human somatic cells—telomere length reduces with each cellular division until senescence is induced at a critical length. This is considered to serve as a mechanism for determining a finite cellular life span, and thus the link between telomeres, cancer, and aging has been of wide interest (Blasco 2007; Cheung and Deng 2008). A fuller understanding of telomere homeostasis is therefore an important goal, critical for understanding cellular senescence and the mechanisms by which the response to DNA damage is appropriately regulated and/or limited in eukaryotic cells. S. cerevisiae provides an excellent model in which to carry out such studies.

In S. cerevisiae, Cdc13 is a single-stranded DNA (ssDNA)-binding protein that binds to short ssDNA overhangs at telomeres and plays at least two important roles at telomeres: (1) recruitment of telomerase (Nugent et al. 1996) and (2) telomere capping (Garvik et al. 1995). The cdc13-1 point mutation confers temperature sensitivity such that Cdc13-1 is proficient in telomere capping at the permissive temperature (23°) but deficient at the nonpermissive temperature (>26°). Thus, in cdc13-1 mutant cells grown at ≥26°, telomeres become “uncapped” and recognized as sites of DNA damage, eliciting a checkpoint response (Garvik et al. 1995). Once uncapped, the telomeres are vulnerable to 5′–3′ exonuclease activity, which can generate extensive regions of ssDNA, thus amplifying the DNA damage signal.

Applying a temperature shift to S. cerevisiae cells harboring the cdc13-1 mutation is a simple method by which telomere capping can be compromised and the response to DNA damage at chromosome ends can be induced and studied. For this reason cdc13-1 has proven to be an informative tool for identifying genes whose products function at uncapped telomeres and in the DNA damage response. For example, cdc13-1 was the primary tool used to show that Mec1, Mec3, Rad53 (Mec2), Rad17, and Rad24 are involved in DNA damage checkpoint control (Weinert et al. 1994). Similarly, deletion of the EXO1 gene, which encodes a 5′–3′ exonuclease, allows cdc13-1 mutant cells to grow and divide at 27°, thus efficiently suppressing the temperature-sensitive telomere-capping defect (Maringele and Lydall 2002; Zubko et al. 2004). This led to the discovery that Exo1 resects the ends of unprotected telomeres in at least two different situations (cdc13-1 mutants and yku70Δ cells), resulting in long stretches of ssDNA, which, in turn, act as a potent DNA damage signal (Maringele and Lydall 2002; Zubko et al. 2004). Importantly, the role of EXO1 and checkpoint genes in responding to uncapped telomeres appears to be conserved in mammals because it has been shown that deletion of exonuclease-1 or the CDK inhibitor p21 leads to an extension of life span in a mouse telomerase knockout model (Choudhury et al. 2007; Schaetzlein et al. 2007). Therefore the identification of new genetic interactions similar to those between RAD9 or EXO1 and cdc13-1 in yeast has the potential to identify novel conserved molecular pathways involved in the response to telomere uncapping, for example (Maringele and Lydall 2002; Zubko et al. 2004).

Here we describe a genomewide screen for gene deletion mutations that demonstrate synthetic genetic, suppressor, or enhancer interactions with the cdc13-1 mutation. Previously, we described the identification and characterization of a novel, evolutionarily conserved, telomere regulator complex (Downey et al. 2006). The results of the complete screen reveals that multiple cellular processes influence telomere capping and/or the response to telomere uncapping.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Genomewide screens:

During the progression of this study, approaches to performing genomewide genetic screens evolved considerably; for example, yeast growth tests progressed from manual to robotic spotting and from scoring by eye to scoring by photography and automated image analysis. The evolution of the screening process is described in supplemental material and supplemental Table S1.

Strains:

Strains used in this study are described in supplemental Table S2.

Synthetic genetic array:

The synthetic genetic array (SGA) technique (Tong et al. 2001; Tong and Boone 2006) was used to combine a genomewide collection of gene deletions with the recessive cdc13-1 temperature-sensitive mutation, flanked by the selectable LEU2 and URA3 markers (Tong et al. 2001; Downey et al. 2006; Tong and Boone 2006). This technique was first performed on a Virtek Versarray Robot (BioRad) in 768-spot format, using a 768- × 1-mm pin tool and, subsequently, in 1536-spot format on a Biomatrix BM3-09 robot (S&P Robotics, Toronto) using a 384- × 1-mm pin tool (supplemental Table S1).

Temperature oscillation:

The UP–DOWN assay was performed in a programmable Sanyo 153 incubator. Plates were incubated at 20° for 5 hr followed by 36° for 5 hr, and this cycle was repeated a total of three times. Incubation was then continued at 20° for the remainder of the experiment and plates were photographed as described above.

Gene ontology analysis:

Version 2.4.0 of GOStats (Falcon and Gentleman 2007) was used with the cutoff set to P = 0.00001 (empirically determined as returning no overrepresented terms from random lists of genes) and the test-type set as conditional. Genes identified in this study were compared to a list of 4292 screened genes, not including slow growers, strains that consistently perform poorly in SGA analysis (Tong et al. 2001), or genes encoding markers used in strain construction (e.g., CAN1). Gene ontology (GO) term annotations were current as of December 18, 2007.

Gene list analysis:

For systematic analysis of ontology annotations and convenient access to gene functional information, OSPREY (Breitkreutz et al. 2003) was used to access the Biogrid database (Stark et al. 2006; Breitkreutz et al. 2008).

Hierarchical clustering:

Data from multiple high-throughput studies were collated and converted to a simplified scoring system as described in the supplemental Methods. These were then analyzed alongside our own data by hierarchical clustering using Cluster 3.0 for Mac OS X (Michiel de Hoon, Seiya Imoto, and Satoru Miyano, Human Genome Center, University of Tokyo). Genes were clustered by centroid linkage using the “absolute correlation (uncentered)” similarity metric (Eisen et al. 1998) based on properties defined in 10 categories: suppressors, enhancers, UP–DOWN assay, telomere length (Askree et al. 2004; Gatbonton et al. 2006; Shachar et al. 2008), nonsense-mediated decay upregulation (He et al. 2003), regulation in response to MMS (Jelinsky and Samson 1999), sensitivity to MMS (Chang et al. 2002), sensitivity to UV (Birrell et al. 2001), sensitivity to ionizing radiation (Bennett et al. 2001), and requirement for replication of Brome mosaic virus (Kushner et al. 2003); see supplemental Methods. Clustering was displayed using Treeview (Saldanha 2004).

RESULTS

A screen for gene deletions that suppress or enhance cdc13-1 temperature sensitivity was undertaken using the SGA technique (Tong et al. 2001; Tong and Boone 2006) as described in materials and methods and supplemental Methods. High-throughput yeast spot tests (materials and methods; supplemental Methods; Figure 1) were used to identify gene deletions, which allowed growth of strains carrying the cdc13-1 mutation at the otherwise nonpermissive temperature of 27°. Five of these (identified during initial screens 1 and 2; supplemental Table S1) were described previously (Downey et al. 2006). At the end of a comprehensive screening process during which a minimum of 4 and a maximum of 15 biological replicates for each viable gene deletion had been tested (supplemental Table S1), a high confidence list of 238 gene deletion suppressors of cdc13-1 temperature sensitivity was obtained (Table 1). Of these 238, 37 strains that grew at the higher nonpermissive temperature of 28° (screens 3 and 4, supplemental Table S1) were classed as strong suppressors (Table 1). A number of gene deletions that have previously been described as cdc13-1 suppressors were identified in our screen (Table 2). These included deletions of RAD9, RAD17, RAD24, EXO1, and CHK1 among the group of strong suppressors (Table 1), consistent with previous studies (e.g., Maringele and Lydall 2002; Zubko et al. 2004).

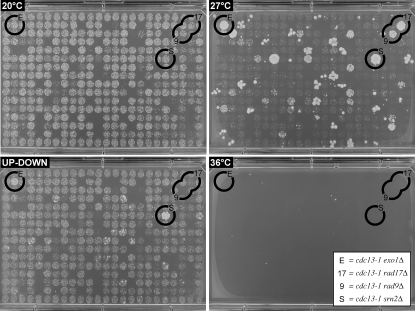

Figure 1.—

High-throughput robotic yeast growth assay in 384-spot format. A total of 384 yeast strains were spotted onto four solid agar plates, each of which was incubated under different conditions, indicated in the top left corner of each panel (20°, 27°, 36°, and the UP–DOWN assay). Circles are drawn around examples of UDS (9, rad9Δ; 17, rad17Δ) and UDR (E, exo1Δ; S, srn2Δ) strains, all four of which are also cdc13-1 suppressors.

TABLE 1.

Genes whose deletion rescues temperature sensitivity of cdc13-1

| Strong suppressors

|

Suppressors

|

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ORF | Gene | ORF | Gene | ORF | Gene | ORF | Gene | ORF | Gene | ORF | Gene |

| YOL138C | RTC1a | YBR147W | RTC2 | YKL087C | CYT2 | YKL008C | LAC1 | YAL023C | PMT2 | YNL224C | SQS1 |

| YER177W | BMH1 | YHR087W | RTC3 | YGL078C | DBP3 | YJL134W | LCB3 | YPL144W | POC4 | YLR119W | SRN2 |

| [YFL023W | BUD27] | YNL254C | RTC4 | YFL001W | DEG1 | YNL323W | LEM3 | YIL160C | POT1 | YHR066W | SSF1 |

| YBR274W | CHK1 | YOR118W | RTC5 | YKR035W-A | DID2 | YLR451W | LEU3 | YBL068W | PRS4 | YBR283C | SSH1 |

| [YJR109C | CPA2] | YPL183W-A | RTC6 | YGR227W | DIE2 | YDL051W | LHP1 | [YDL006W | PTC1] | YLR150W | STM1 |

| YIL036W | CST6 | YDL119C | YDL119C | YKL213C | DOA1 | YJR070C | LIA1 | YDR496C | PUF6 | YDR320C | SWA2 |

| YPL194W | DDC1 | YGR201C | YGR201C | YDR206W | EBS1 | YNL307C | MCK1 | YPR191W | QCR2 | YNL081C | SWS2 |

| [YNL080C | EOS1] | YIL055C | YIL055C | YBL047C | EDE1 | YPL098C | MGR2 | YKR055W | RHO4 | YLR354C | TAL1 |

| YOR033C | EXO1 | YIL057C | YIL057C | YKL048C | ELM1 | YLR035C | MLH2 | YNL180C | RHO5 | YIL011W | TIR3 |

| YCR034W | FEN1 | YIL161W | YIL161W | YDR512C | EMI1 | YIL110W | MNI1 | YIL053W | RHR2 | YPR074C | TKL1 |

| YMR058W | FET3 | YLR404W | YLR404W | YMR015C | ERG5 | YPR045C | MNI2 | YLR453C | RIF2 | YER007C-A | TMA20 |

| [YLR192C | HCR1] | YIL079C | AIR1 | [YML008C | ERG6] | YIR002C | MPH1 | YIL066C | RNR3 | YJR014W | TMA22 |

| YOL095C | HMI1 | YER073W | ALD5 | YER145C | FTR1 | YKL062W | MSN4 | YDL082W | RPL13A | YGR260W | TNA1 |

| YMR080C | NAM7 | YPL061W | ALD6 | YPL262W | FUM1 | YPR134W | MSS18 | [YKL006W | RPL14A] | YNL070W | TOM7 |

| YHR077C | NMD2 | YGL148W | ARO2 | YBL016W | FUS3 | YBR057C | MUM2 | YBR084C-A | RPL19A | YNL121C | TOM70 |

| YOR209C | NPT1 | YDR101C | ARX1 | YIL097W | FYV10 | YHR004C | NEM1 | YPL079W | RPL21B | YIL138C | TPM2 |

| YPL052W | OAZ1 | [YMR116C | ASC1] | YOR183W | FYV12 | YLR363C | NMD4 | YFR031C-A | RPL2A | YPL030W | TRM44 |

| YDL232W | OST4 | YKL185W | ASH1 | YMR307W | GAS1 | YER002W | NOP16 | YLR406C | RPL31B | YLR425W | TUS1 |

| YOR368W | RAD17 | YBL089W | AVT5 | YJR040W | GEF1 | YNL183C | NPR1 | YOR234C | RPL33B | YER151C | UBP3 |

| YER173W | RAD24 | YIL124W | AYR1 | YGL020C | GET1 | YNL099C | OCA1 | YER056C-A | RPL34A | YFR010W | UBP6 |

| YDR217C | RAD9 | YKR099W | BAS1 | YHL031C | GOS1 | YNL056W | OCA2 | YDL191W | RPL35A | YMR067C | UBX4 |

| YLR039C | RIC1 | YPL115C | BEM3 | YOL059W | GPD2 | YCR095C | OCA4 | [YLR185W | RPL37A] | YBR273C | UBX7 |

| YCR028C-A | RIM1 | YDR099W | BMH2 | YDL035C | GPR1 | YDR067C | OCA6 | YDR500C | RPL37B | YDL190C | UFD2 |

| YNL069C | RPL16B | YIL159W | BNR1 | YML121W | GTR1 | YML060W | OGG1 | [YPR043W | RPL43A] | YNL229C | URE2 |

| YDR389W | SAC7 | YFL025C | BST1 | YGL084C | GUP1 | YGR202C | PCT1 | YBR031W | RPL4A | YKR042W | UTH1 |

| YDR143C | SAN1 | YAR014C | BUD14 | YGL237C | HAP2 | [YER178W | PDA1] | YLR448W | RPL6B | YDL077C | VAM6 |

| YER120W | SCS2 | [YGR262C | BUD32b] | YBL021C | HAP3 | YER153C | PET122 | YGL147C | RPL9A | YGL212W | VAM7 |

| [YOR035C | SHE4] | YIL034C | CAP2 | YOR358W | HAP5 | YOR017W | PET127 | YER139C | RTR1 | YIL135C | VHS2 |

| YDL033C | SLM3 | YGR174C | CBP4 | YCR065W | HCM1 | YLR191W | PEX13 | YLR180W | SAM1 | YIL017C | VID28 |

| YOR327C | SNC2 | YKL208W | CBT1 | YHL002W | HSE1 | YOL044W | PEX15 | YDR181C | SAS4 | YKR001C | VPS1 |

| YLR313C | SPH1 | YML036W | CGI121c | YGL253W | HXK2 | YAL055W | PEX22 | YKL051W | SFK1 | YPL120W | VPS30 |

| YLR372W | SUR4 | YIL035C | CKA1 | [YJR118C | ILM1] | YDR329C | PEX3 | YNL032W | SIW14 | YJL154C | VPS35 |

| YBR126C | TPS1 | YOR061W | CKA2 | YDR315C | IPK1 | YGR133W | PEX4 | YLR398C | SKI2 | YKR020W | VPS51 |

| YBR082C | UBC4 | YOR039W | CKB2 | YFR055W | IRC7 | YGR231C | PHB2 | YPR189W | SKI3 | YDR486C | VPS60 |

| YGR072W | UPF3 | YOL008W | COQ10 | YGL016W | KAP122 | YJL117W | PHO86 | YOR076C | SKI7 | YIL101C | XBP1 |

| YOR089C | VPS21 | YPL172C | COX10 | YHR158C | KEL1 | YCR037C | PHO87 | YGL213C | SKI8 | YIL023C | YKE4 |

| YAL002W | VPS8 | YLL009C | COX17 | YNL238W | KEX2 | YGL023C | PIB2 | YNL311C | SKP2 | YBR104W | YMC2 |

| YHR116W | COX23 | YJL094C | KHA1 | [YML061C | PIF1b] | YBL007C | SLA1 | YDR349C | YPS7 | ||

| [YMR256C | COX7] | YAR018C | KIN3 | YDR466W | PKH3 | YGR229C | SMI1 | [YLR262C | YPT6] | ||

| YDL117W | CYK3 | YNL322C | KRE1 | YDL095W | PMT1 | YER161C | SPT2 | YML001W | YPT7 | ||

| YOR065W | CYT1 | ||||||||||

Underlined genes lie adjacent to other genes whose deletion rescues cdc13-1. In such cases, an effect on transcription of the neighboring gene cannot be discounted. Brackets indicate genes previously identified as synthetic with wild-type during SGA (Tong et al. 2001).

The RTC gene name is reserved for previously unnamed ORFs.

Deletion of PIF1 and BUD32 rescues cdc13-1 (Downey et al. 2006) but these genes were not tested further in robotic assays due to slow growth.

Deletion of CGI121 rescues cdc13-1 (Downey et al. 2006) but this was not detected in robotic assays subsequent to initial scoring.

TABLE 2.

Comparison of expected cdc13-1 suppressors with actual results and testing of novel suppressors in an alternative genetic background

| Gene deletion | Suppressor of cdc13-1 in BY4741 (this work) | Suppressor of cdc13-1 in W303 (this work) | Previously documented suppressor of cdc13-1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| rad9Δ | ++ | NA | + |

| chk1Δ | ++ | NA | + |

| ddc1Δ | ++ | NA | + |

| rad24Δ | ++ | NA | + |

| rad17Δ | ++ | NA | + |

| upf3Δ | ++ | NA | + |

| nmd2Δ | ++ | NA | + |

| nam7Δ | ++ | NA | + |

| exo1Δ | ++ | NA | + |

| bub2Δ | − | NA | + |

| mec3Δ | −a | NA | + |

| bmh1Δ | + | NA | + (Downey et al. 2006) |

| san1Δ | ++ | NA | + (Downey et al. 2006) |

| pif1Δ | +b | NA | + (Downey et al. 2006) |

| cgi121Δ | +c | NA | + (Downey et al. 2006) |

| ebs1Δ | + | NA | + (Downey et al. 2006) |

| scs2Δ | ++ | + | − |

| poc4Δ | + | + | − |

| snc2Δ | ++ | + | − |

| pkh3Δ | + | + | − |

| pda1Δ | + | + | − |

| oca1Δ | + | + | − |

| oca2Δ | + | + | − |

| siw14Δ (oca3Δ) | + | + | − |

| oca4Δ | + | + | − |

| oca6Δ | + | + | − |

| oca5Δ | − | + | − |

++, yes, a strong suppressor; +, yes; −, no.

Deletion of MEC3 rescues cdc13-1 but was not tested in robotic assays due to slow growth.

Deletion of PIF1 rescues cdc13-1 (Downey et al. 2006) but was not tested further in robotic assays due to slow growth.

Deletion of CGI121 rescues cdc13-1 (Downey et al. 2006) but was not detected in robotic assays subsequent to initial scoring.

Our approach also allowed us to identify gene deletions that were lethal or sick in combination with cdc13-1 because double mutants were either missing or poor growers after SGA (materials and methods; supplemental Methods; supplemental Figure S2). Twenty genes demonstrated synthetic lethal and 32 showed synthetic-sick interactions with cdc13-1 at 20° (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Genes whose deletion exacerbates the growth defects of cdc13-1 cells

| Synthetic lethal

|

Synthetic sick

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ORF | Gene | ORF | Gene | ORF | Gene |

| YJL123C | MTC1a | YKL098W | MTC2 | YMR035W | IMP2 |

| YNL196C | YNL196C | YGL226W | MTC3 | YGR238C | KEL2 |

| YOR058C | ASE1 | YBR255W | MTC4 | YOL064C | MET22 |

| YGL029W | CGR1 | YDR128W | MTC5 | YKL167C | MRP49 |

| YBR036C | CSG2 | YHR151C | MTC6 | YOL041C | NOP12 |

| YHR059W | FYV4 | YDL218W | YDL218W | YML103C | NUP188 |

| YEL003W | GIM4 | YIL040W | APQ12 | YBR093C | PHO5 |

| YNL014W | HEF3 | YBR131W | CCZ1 | YIL153W | RRD1 |

| YOL108C | INO4 | YGR157W | CHO2 | YHR178W | STB5 |

| YNL106C | INP52 | YGL078C | DBP3b | YBR231C | SWC5 |

| YKL176C | LST4 | YCL016C | DCC1 | YNL081C | SWS2b |

| YGR078C | PAC10 | YDL219W | DTD1 | YJL138C | TIF2 |

| YNL015W | PBI2 | YLR342W | FKS1 | YPR173C | VPS4 |

| YNL003C | PET8 | YDL222C | FMP45 | YPR024W | YME1c |

| YBL027W | RPL19B | YHR108W | GGA2 | YGL255W | ZRT1 |

| YGR118W | RPS23A | YML121W | GTR1b | YOL012C | HTZ1 |

| YNL206C | RTT10 | ||||

| YOR297C | TIM18 | ||||

| YNL197C | WHI3 | ||||

| YMR302C | YME2 | ||||

Underlined genes lie adjacent to other genes whose deletion has synthetic interactions with cdc13-1. In such cases, an effect on transcription of the neighboring gene cannot be discounted.

The MTC gene name is reserved for previously unnamed ORFs.

Also a suppressor of cdc13-1 (see Table 1).

Also classed as UDS.

In the discussion, we speculate on the roles of these cdc13-1 suppressor and enhancer genes in telomere biology.

Conservation of suppression in an alternative genetic background:

It is possible that second-site mutations in gene deletion strains were responsible for suppression of the cdc13-1 temperature-sensitive phenotype. Therefore, to confirm that the relevant gene deletions suppressed cdc13-1, 10 suppressor genes were deleted by transformation in the different W303 cdc13-1 genetic background and tested for growth at 26°, 26.5°, and/or 27°. In all 10 cases, growth was observed at a higher temperature than the control cdc13-1 strains (Table 2). In addition, as a result of identification of OCA1, OCA2, SIW14 (OCA3), OCA4, and OCA6 as suppressors of cdc13-1, we also tested deletion of the OCA5 gene in the W303 genetic background and found it to suppress (Table 2); OCA5 was dropped from the list of suppressors in this study at the screen 5 stage (see supplemental Methods). Since 10/10 gene deletions that we identified through high-throughput screening also suppress cdc13-1 in the W303 genetic background, we conclude that the majority of the cdc13-1 suppressors that we have identified are likely to be true suppressors.

The UP–DOWN screen:

Given the large number of cdc13-1 suppressors, we wanted to differentiate between different types of cdc13-1 suppressors. Therefore, we also screened for gene deletions that, when combined with the cdc13-1 mutation, significantly enhanced or reduced cell viability in a temperature oscillation (or “UP–DOWN”) experiment (materials and methods). The cdc13-1 mutation has a reversible temperature-sensitive phenotype; that is, cells with the cdc13-1 mutation maintain high viability and efficiently form colonies when returned to permissive temperature after short periods at nonpermissive temperature. DNA damage checkpoint pathways, which inhibit cell division in response to uncapped telomeres in cdc13-1 mutants, are important for maintaining cdc13-1 cell viability (Weinert et al. 1994; Zubko et al. 2004). In addition, nucleases and nuclease inhibitors, which affect single-stranded DNA production at uncapped telomeres of cdc13-1 mutants, affect the ability of cdc13-1 to grow for periods at nonpermissive temperature.

In an UP–DOWN assay, cdc13-1 mutants are cycled between permissive and nonpermissive conditions and then allowed to form colonies at permissive temperature. In an UP–DOWN assay, rad9Δ cdc13-1 strains do not form colonies efficiently because they do not arrest cell division in response to telomere uncapping and accumulate very high levels of single-stranded DNA. Conversely, exo1Δ cdc13-1 cells grow demonstrably faster than EXO+ RAD+ cdc13-1 strains in this assay (Zubko et al. 2004; Figure 1), presumably because high levels of Exo1-dependent ssDNA at telomeres of cdc13-1 cells inhibit cell division for long periods even after cells are returned to permissive temperature. Therefore, we hypothesized that an UP–DOWN screen would allow us to identify genes that interact with cdc13-1 in a RAD9-like or EXO1-like manner.

The UP–DOWN assay was performed on between 2 and 10 biological replicates of cdc13-1 SGA strains. Those gene deletions that, in conjunction with cdc13-1, showed consistently poor growth (Figure 1) were scored as UP–DOWN sensitive (UDS) while those that grew consistently better than cdc13-1 his3∷KANMX controls (Figure 1) were scored as UP–DOWN resistant (UDR) (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Genes whose deletion imparts a phenotype in the cdc13-1 UP–DOWN assay

| UD sensitive

|

UD sensitive

|

UD sensitive

|

UD resistant

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ORF | Gene | ORF | Gene | ORF | Gene | ORF | Gene |

| YEL033W | MTC7a | YJR075W | HOC1 | YML032C | RAD52 | [YMR116C | ASC1b] |

| [YNL171C | YNL171C] | YDR158W | HOM2 | YDR217C | RAD9b | YOR033C | EXO1b |

| [YLR370C | ARC18] | YER052C | HOM3 | YHL027W | RIM101 | YKL029C | MAE1 |

| YLR242C | ARV1 | YJR139C | HOM6 | YOR275C | RIM20 | YCR009C | RVS161 |

| YJR053W | BFA1 | YJL092W | HPR5 | YPR018W | RLF2 | YLR119W | SRN2b |

| YER016W | BIM1 | [YHR067W | HTD2] | YJL136C | RPS21B | ||

| YLR015W | BRE2 | YIL154C | IMP2′ | [YBL072C | RPS8A] | ||

| [YGR188C | BUB1] | YDR123C | INO2 | YDR289C | RTT103 | ||

| YMR055C | BUB2 | YMR294W | JNM1 | YLL002W | RTT109 | ||

| [YOR026W | BUB3] | YOR123C | LEO1 | YFR040W | SAP155 | ||

| YMR038C | CCS1 | YPL055C | LGE1 | YMR127C | SAS2 | ||

| YLR418C | CDC73 | YAL024C | LTE1 | YDR181C | SAS4b | ||

| YBR274W | CHK1b | YPR164W | MMS1 | YBR171W | SEC66 | ||

| YMR198W | CIK1 | YJL183W | MNN11 | YBL031W | SHE1 | ||

| YPR119W | CLB2 | YCL061C | MRC1 | [YOR035C | SHE4b] | ||

| YCR086W | CSM1 | YPL184C | MRN1 | YER118C | SHO1 | ||

| YPR135W | CTF4 | [YKL009W | MRT4] | YKR101W | SIR1 | ||

| YKR024C | DBP7 | YBR057C | MUM2b | YPR189W | SKI3b | ||

| YPL194W | DDC1b | YNL119W | NCS2 | YMR016C | SOK2 | ||

| YKL213C | DOA1b | YKL040C | NFU1 | YPR032W | SRO7 | ||

| [YDR440W | DOT1] | [YKR082W | NUP133] | YOR027W | STI1 | ||

| YKL204W | EAP1 | YKL120W | OAC1 | YMR039C | SUB1 | ||

| YBL047C | EDE1b | YCR077C | PAT1 | YAR003W | SWD1 | ||

| YOR144C | ELG1 | YGR193C | PDX1 | YBR175W | SWD3 | ||

| YKL048C | ELM1b | YDR276C | PMP3 | [YLR182W | SWI6] | ||

| YMR202W | ERG2 | YPL179W | PPQ1 | YDR260C | SWM1 | ||

| YGL054C | ERV14 | YGR135W | PRE9 | YOL018C | TLG2 | ||

| YLR233C | EST1 | YMR201C | RAD14 | YKR042W | UTH1b | ||

| YLR318W | EST2 | YOR368W | RAD17b | YOR089C | VPS21b | ||

| YIL009C-A | EST3 | YER173W | RAD24b | YMR284W | YKU70 | ||

| YLL043W | FPS1 | YKL113C | RAD27 | YMR106C | YKU80 | ||

| YMR307W | GAS1b | YER162C | RAD4 | YPR024W | YME1c | ||

| YDR108W | GSG1 | ||||||

Underlined genes lie adjacent to other genes whose deletion imparts a phenotype in the UP–DOWN assay distinct from cdc13-1 alone. In such cases, an effect on transcription of the neighboring gene cannot be discounted. Brackets indicate genes previously identified as synthetic with wild type during SGA (Tong et al. 2001).

The MTC gene name is reserved for previously un-named ORFs.

Also a suppressor of cdc13-1 and so “RAD9-like” (see Table 1).

Also classed as synthetic sick.

A total of 96 UDS and five UDR genes were identified. Interestingly, both classes included both genes that suppress cdc13-1 when deleted and genes that do not. The 15 UDS genes that are cdc13-1 suppressors included RAD9, RAD17, RAD24, and CHK1, which have well-characterized roles in coordinating the DNA damage response to uncapped telomeres, indicating that other novel genes with this “RAD9-like” phenotype are likely to be of interest. The 81 UDS genes that are not cdc13-1 suppressors included YKU70, YKU80, EST1, EST2, and EST3. These, too, have well-defined roles in telomere biology, indicating that this class is also likely to contain novel genes of interest. Deletion of YKU70, YKU80, and others in this category has previously been reported to be synthetically sick with cdc13-1 (Polotnianka et al. 1998). However, since we germinated spores at 20°, rather than the 23° or 25° that is more usually used to grow cdc mutants, we probably masked the YKU70/80 cdc13-1 synthetic-sick interactions previously reported. Presumably, other synthetic-sick interactions were also missed. There was only one gene (YME1) that reproducibly fell into both categories. Three of the five UDR genes were also cdc13-1 suppressors and hence EXO1-like; however, the only gene in this category that has previously been connected to telomere biology is EXO1 itself.

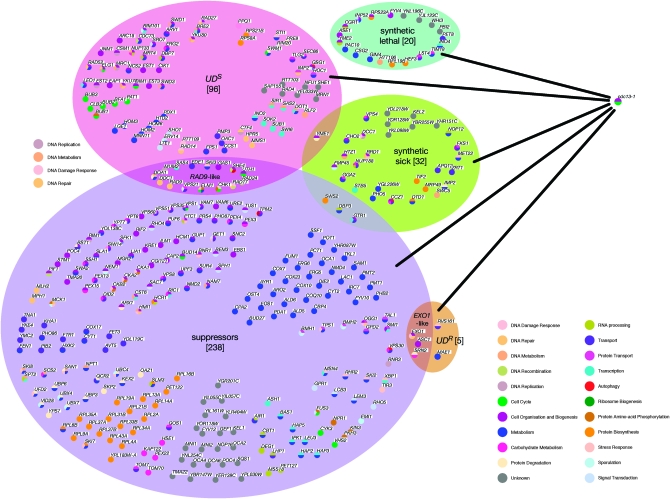

Thus, through a systematic and iterative process, we arrived at a reliable classification of genes as one or more of the following: cdc13-1 suppressor, UDS, RAD9-like, UDR, EXO1-like, cdc13-1 synthetic lethal, and cdc13-1 synthetic sick (Tables 1, 3, and 4; Figure 2).

Figure 2.—

Summary of cdc13-1 interactors. Genes designated as cdc13-1 suppressors (purple shaded area), UDS (red), UDR (orange), synthetic sick (green), and synthetic lethal with cdc13-1 (blue) were arranged using OSPREY. Genes belonging to more than one category (including RAD9-like and EXO1-like genes) are indicated in the overlap regions of shaded areas. Individual genes are represented as solid circles, color coded by OSPREY with each color representing a gene ontology term, up to a maximum of four. Relevant gene ontology terms are indicated in the color key.

Neighboring genes that interact with cdc13-1:

In our lists of cdc13-1 interactors, we identified a number of pairs or sets of genes that are adjacent to each other in the genome. For example, YIL034C (CAP2), YIL035C (CKA1), and YIL036W (CST5) are all classed as cdc13-1 suppressors (Table 1). A likely explanation for such a group is that one gene has a true genetic interaction with cdc13-1 and disruption of the neighboring gene(s) affects the expression of the gene of interest. Indeed, a previous study (Alvaro et al. 2007) has demonstrated that deletion of either overlapping or adjacent open reading frames can occasionally result in false positives in genomewide screens such as these. An inference can be made as to whether a gene is a true interactor or is having an effect on transcription of neighboring genes. In the case of CKA1 (above), for example, the identification of two other subunits of casein kinase, CKA2 and CKB2, as suppressors (neither of which lie adjacent to other suppressors in the yeast genome) supports classification of CKA1 as a suppressor. Also, genes with previously well-characterized roles in telomere/checkpoint biology such as CHK1 (adjacent to UBX7) may safely be assumed to be classified correctly. However, in most cases, inferring a role is potentially misleading. We have therefore highlighted (by underlining or boldface text in Tables 1, 3, 4, and 5; Figure 3) genes that, within a particular classification, lie near each other on the chromosome and have omitted them from statistical analyses of GO.

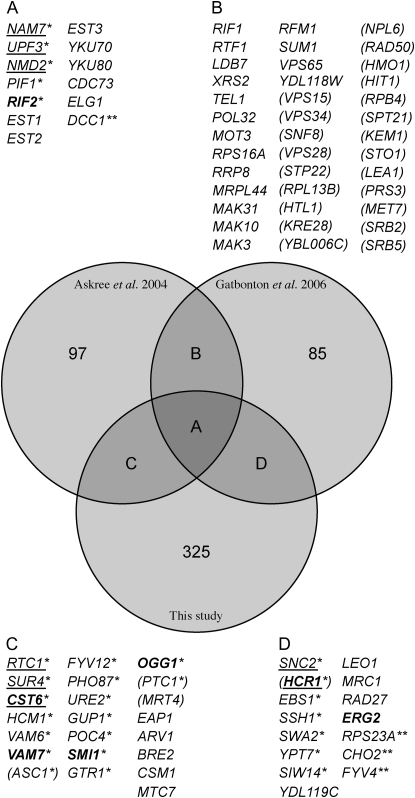

Figure 3.—

Comparison of CDC13-interacting genes with telomere length genes. A Venn diagram shows hits from two separate genomewide screens for telomere length regulating genes compared to a list of cdc13-1 interactors. Lists of genes that make up the cross sections between studies are displayed and indicated by letters. The numbers of genes in each segment are indicated. Boldface text highlights genes that have neighboring genes in the genome whose deletion results in a similar phenotype. *cdc13-1 suppressor (strong suppressors are underlined); **synthetic (sick or lethal) with cdc13-1; genes in parentheses either were not tested in this study due to slow growth or were identified previously as giving consistently poor performance in SGA studies.

Gene ontology analysis of interactors:

To better understand the types of processes that interact with uncapped telomeres, the different classes of cdc13-1-interacting genes were subjected to statistical analysis using the GOstats Bioconductor package (Falcon and Gentleman 2007). GOstats analysis (supplemental Table S3) allowed us to identify GO terms that were overrepresented. Genes previously identified as having roles in telomere maintenance (GO:0000723) are overrepresented in the results from both the cdc13-1 suppressor screen (23 genes annotated as GO:0000723) and the UP–DOWN assay (18 more genes annotated as GO:0000723); 3 genes annotated as both “telomerase activity” (GO:0003720) and “telomerase holoenzyme complex” (GO:0005697): EST1, EST2, and EST3 (supplemental Table S3). The list of strong suppressors (Table 1) is enriched for genes involved in DNA damage checkpoint control—namely DDC1, RAD17, RAD24, and RAD9—and in nonsense-mediated decay—namely NAM7, NMD2, and UPF3. RAD9-like genes (see Table 4) included the same four genes involved in DNA damage checkpoint control (DDC1, RAD17, RAD24, and RAD9) together with the “cell-cycle checkpoint” (GO:0000075) annotated ELM1. Finally, the UDS genes that do not suppress cdc13-1 temperature sensitivity when deleted had multiple overrepresented GO terms describing aspects of chromosome architecture (supplemental Table S3).

All of the processes highlighted by statistical analysis of cdc13-1 interactors have well-characterized links to telomere biology. This analysis clearly shows that our screens were successful in identifying known CDC13 interactors and suggests therefore that genes identified in this study that were not previously linked to telomeres are likely to have telomere-related roles.

Systematic analysis of gene lists:

One caveat with statistical analysis of GO terms is that annotations may be biased toward processes that have been extensively studied. Also, we used a relatively high P-value cutoff (materials and methods) to mitigate the likelihood of false positives. We therefore performed a different systematic analysis of cdc13-1 interactors, which this time included all genes identified in our study (see above; Tables 1, 3, and 4). We grouped genes with clearly related functions together, irrespective of GO term frequency and chromosomal position, using the functional descriptions in BioGrid (Stark et al. 2006; Breitkreutz et al. 2008).

Suppressors of cdc13-1 temperature sensitivity (Table 1) included clusters of genes involved in bud-site selection; mitochondrial function (including multiple genes for electron transport, mitochondrial genome integrity, mitochondrial ribosomes, and mitochondrial integrity); nonsense-mediated decay; chromatin architecture; phosphate transport; signal transduction; ribosome function; protein degradation; mRNA degradation; vesicular transport; response to DNA damage; iron ion transport; the actin cytoskeleton, cell polarity and mRNA localization; and HO function (Table 5). Also of note in this category were five putative tyrosine phosphatases of largely unknown function [OCA1, OCA2, SIW14 (OCA3), OCA4, and OCA6)], four killer-toxin-related genes, two aldehyde dehydrogenase genes, three genes from the CCAAT-binding complex, and three of four subunits of casein kinase 2 (Table 5).

TABLE 5.

Groups of functionally related genes among cdc13-1 interactors

| Group | Function of related genes | Suppressors | UP–DOWN | Synthetic |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | DNA repair/DNA damage checkpoint/telomeres | MLH2, MPH1, CHK1, DDC1, EXO1, RAD17, RAD24, RAD9, DOA1 | CHK1,aDDC1,aRAD17,aRAD24,aRAD9,aMRC1, RAD14, RAD4, RAD27, RAD52, YKU70, YKU80, ELG1, DOA1,aHPR5, MMS1, IMP2 | |

| 2 | Protein degradation | UBP3, UBP6, UBX4, UBX7, UFD2, DOA1, UBC4, SAN1, VID28, POC4 | PRE9 | |

| 3 | Nonsense-mediated decay | NMD4, NAM7, UPF3, EBS1, NMD2 | ||

| 4 | Chromatin architecture/silencing/histone modification | SCS2, SPT2, NPT1, SAS4, RIF2 | [SAS2, SAS4;a SAS complex], [SWD1, SWD3, BRE2; COMPASS complex], [CDC73, LEO1; Paf1 complex], DOT1, SIR1, RLF2, LGE1 | [SWC5, HTZ1; SWR1 complex] |

| 5 | Vesicular transport | PEX13, PEX15, PEX22, PEX3, PEX4, VAM6, VAM7, YPT6, YPT7, VPS1, VPS30, VPS35, VPS51, VPS60, DID2, SRN2, HSE1, PIB2, RIC1, VPS21, VPS8, SWA2, SSH1, SNC2, GOS1 | [MNN11, HOC1; golgi mannosyl transferase complex], ERV14, SEC66, TLG2, RUD3, GSG1, SRO7, SRN2a | CCZ1, PBI2,bVPS4 |

| 6 | Casein kinase 2 | CKA1, CKA2, CKB2 | ||

| 7 | Ribosome function | RPL13A, RPL14A, RPL19A, RPL21B, RPL2A, RPL31B, RPL33B, RPL34A, RPL35A, RPL37A, RPL37B, RPL43A, RPL4A, RPL6B, RPL9A, RPL16B, NOP16, ARX1, ASC1, DBP3, HCR1, TMA20, TMA22 | RPS21B, RPS8A, ASC1,aDBP7, MRT4 | RPL19B,bDBP3,aRPS23A,bNOP12, CGR1b |

| 8 | Mitochondrial electron transport/genome/ribosomes and integrity | MSS18, COX7, COX10, COX17, COX23, CYT1, CYT2, QCR2, CBP4, COQ10, PET122, PET127, ILM1, PIF1, MGR2, HMI1, RIM1, TOM7, TOM70,YMC2, YDL119C, SWS2, [HAP2, HAP3, HAP5; CCAAT-binding complex] | UTH1a | SWS2,aMRP49, TIM18,bYME1, YME2b |

| 9 | Tyrosine phosphatase | OCA1, OCA2, OCA4, OCA6, SIW14 | ||

| 10 | Signal transduction | BMH1, BMH2 | ||

| 11 | Bud site selection | BEM3, BUD14, BUD27 | ||

| 12 | Actin cytoskeleton/cell polarity/mRNA localization | EDE1, RHO4, BNR1, SLA1 | EDE1*, ARC18, RVS161 | |

| 13 | Ergosterol biosynthesis | ERG5, ERG6 | ERG2 | |

| 14 | Iron ion transport | FTR1, FET3 | ||

| 15 | Aldehyde dehydrogenases | ALD5, ALD6 | ||

| 16 | HO function | ASH1, PUF6, SHE4 | SHE4a | |

| 17 | mRNA degradation | SKI2, SKI3, SKI7, SKI8 | SKI3a | |

| 18 | Phosphate transport | PHO86, PHO87 | ||

| 19 | Killer toxin related | FYV10, FYV12, KRE1 | FYV4b | |

| 20 | Protein O mannosylation | PMT1, PMT2 | ||

| 21 | Telomerase holoenzyme | EST1, EST2, EST3 | ||

| 22 | Spindle checkpoint | BUB1, BUB3, BIM1 | ||

| 23 | Mitotic exit network | KEL1 | BFA1, BUB2, LTE1, SWM1 | KEL2 |

| 24 | Transposition | RTT103, RTT109 | RTT106b | |

| 25 | Glycerol osmosensing | SHO1, FPS1 | ||

| 26 | Methionine/threonine biosynthesis | HOM2, HOM3, HOM6 |

Genes in boldface lie adjacent to other cdc13-1 interactors of the same category (e.g., synthetic); strong suppressors are underlined. A number for each group of genes is indicated on the left.

Also a suppressor of cdc13-1.

Deletion of gene is synthetically lethal with cdc13-1.

A similar analysis of UDS genes (Table 4) identified groups of genes with roles in the telomerase holoenzyme: the spindle checkpoint; the mitotic exit network; the DNA damage checkpoint; regulation of transcription termination and transposition; ribosome function; chromosome architecture (including multiple SAS complex, COMPASS complex, and Paf1 complex genes); the actin cytoskeleton, cell polarity and mRNA localization; glycerol osmosensing; methionine and threonine synthesis; and vesicular transport (Table 5).

Finally, analysis of genes whose deletion exacerbates the cdc13-1 phenotype (Table 3) provided multiple “hits” affecting ribosome function, mitochondrial integrity, and histone H2AZ exchange (chromatin remodeling) (Table 5).

Uncharacterized genes identified in the cdc13-1 screen:

A number of genes identified as cdc13-1 interactors in this study were of previously unknown function. Suppressor genes, when present, have a negative effect on telomere capping in cdc13-1 mutant cells at the nonpermissive temperature; therefore we have named such genes RTC (restriction of telomere capping; Table 1). Genes of previously unknown function whose deletion exacerbates the cdc13-1 phenotype have been named MTC (maintenance of telomere capping) since their presence increases the fitness of cdc13-1 mutant cells at permissive temperature or during the UP–DOWN assay (Tables 3 and 4). We did not apply new acronyms to otherwise uncharacterized cdc13-1 interactors if (1) they lay next to other cdc13-1 interactors in the genome (see above) or (2) they were classified as dubious open reading frames in the Saccharomyces Genome Database (2008) and were adjacent to other genes that could reasonably account for their deletion phenotype (see supplemental Table S4); however, this could be updated in the future.

DISCUSSION

The objective of our study was to identify proteins and pathways that cap telomeres or regulate the cellular response to uncapped telomeres. We combined the S. cerevisiae gene deletion collection with the well-defined, temperature-sensitive, and reversible cdc13-1 mutation using the SGA strain construction technique and we developed and optimized high-throughput yeast growth assays. Although others have looked systematically for synthetic lethality with temperature-sensitive mutations (e.g., Measday et al. 2005; Baetz et al. 2006), to the best of our knowledge, a genomewide screen for gene deletions that confer subtle suppressor/enhancer phenotypes on a temperature-sensitive mutation has not previously been reported. Our approach therefore complements other high-throughput genetic techniques such as SGA (Tong et al. 2001; Roguev et al. 2007) and synthetic dosage lethal analysis (Measday et al. 2005).

We screened for gene deletions that suppress the lethality of cdc13-1 at the nonpermissive temperature and genes that compromise or contribute to the “reversibility” of cdc13-1 mutants. Combined with synthetic-lethal and synthetic-sick data from the SGA procedure, this resulted in five overlapping categories of CDC13 interactors: suppressors of cdc13-1, synthetic lethal with cdc13-1, synthetic sick with cdc13-1, UDS, and UDR—the latter two categories, respectively, having RAD9-like and EXO1-like subclasses, giving eight classes in all. Many of the genes identified as interacting with CDC13 fit into pathways with previously recognized roles in telomere biology (Table 5). However, a significant number of genes identified in this study have previously uncharacterized relationships to telomere function. A more detailed analysis of their roles is likely to provide novel information about eukaryotic telomere biology; for example, in the same way as Exo1, discovered to have telomere-related function in yeast (Maringele and Lydall 2002), plays a role in life-span determination of telomerase knockout mice (Schaetzlein et al. 2007).

cdc13-1 suppressors:

cdc13-1 suppressors encode proteins that inhibit growth of cdc13-1 mutant cells at the nonpermissive temperature. Previous work has shown that suppression of the temperature sensitivity of cdc13-1 can occur through different pathways and to different extents. For example, deletion of EXO1 (which encodes a 5′–3′ exonuclease required for resection at telomere ends in the event of telomere uncapping) suppresses cdc13-1 temperature sensitivity through a different mechanism from suppression by deletion of RAD9, which is required for signaling cell-cycle arrest. There is therefore no single, simple explanation for the actions of the many novel gene deletions that we have identified as suppressing cdc13-1 (Table 1).

Some of the biological functions common to genes identified as cdc13-1 suppressors (Table 5) have well-understood relationships with telomere function. DNA damage checkpoint and related genes, for example, act at telomeres to detect uncapping and transduce signals to the DNA repair and cell-cycle machinery (group 1, Table 5; supplemental Figure S3) (Lydall 2003; Longhese 2008).

For other “clusters” of genes, there are plausible hypotheses to explain how they might affect telomeres. Genes involved in protein degradation (group 2, Table 5; supplemental Figure S3) could potentially affect the levels of many telomere-associated proteins. An example is SAN1, the product of which functions in ubiquitin-dependent degradation of aberrant proteins in the cell nucleus. San1 degrades the defective Cdc13-1 protein and therefore deletion of SAN1 stabilizes Cdc13-1 levels (Gardner et al. 2005). What little function Cdc13-1 has at elevated temperature might therefore be increased in the absence of SAN1. Deletion of nonsense-mediated decay genes (group 3, Table 5; supplemental Figure S3) alters the stoichiometry of telomere cap components and in particular elevates transcript levels for the essential Cdc13-interacting Stn1 protein (Dahlseid et al. 2003; Enomoto et al. 2004).

Genes that affect chromatin architecture, silencing, and/or histone modification influence telomere biology, presumably by modifying the accessibility of chromatin to telomere proteins, for example (Yu et al. 2007). Chromatin modifiers are represented both as cdc13-1 suppressors and as UDS genes in this category (group 4, Table 5) and at least one silencing gene (SAS4) is RAD9-like in that it is both a suppressor and UDS. Therefore, the relationship between chromatin and the telomere cap is complex. Recent experiments show how the histone H3K79 methyl transferase Dot1 (identifed as UDS in our study) is required for checkpoint activation and inhibition of resection in cdc13-1 mutants (Lazzaro et al. 2008).

A large number of suppressor genes have vesicular trafficking functions (group 5, Table 5). This is consistent with the observation that many vesicular traffic genes affect telomere length (Askree et al. 2004). At least some of those were shown to act upon telomere length in a YKU70-dependent manner (Rog et al. 2005); however, it seems likely from our studies that others may influence Cdc13 function. There are extensive interactions, described in BioGrid, between vesicular traffic genes and other types of cdc13-1 suppressors (supplemental Figure S3); hence mutations that alter vesicular trafficking may affect telomeres through multiple different pathways. It is interesting to note that transport of telomerase proteins and TLC1 RNA across the nuclear membrane is important for telomerase function (Teixeira et al. 2002; Gallardo et al. 2008) and that deletion of KAP122, required for import of TLC1 from the cytoplasm to the nucleus (Gallardo et al. 2008), suppresses cdc13-1.

Phosphorylation by human casein kinase 2 (CK2) has been shown to regulate binding of human Trf1 to telomeres (Kim et al. 2008). Human Trf1 negatively regulates telomere length by inhibiting access of telomerase to telomeres. Possible Trf1 functional homologs in S. cerevisiae are Tbf1 and Rap1, both of which are essential TTAGGG-binding proteins with roles in gene silencing at telomeres (Fourel et al. 1999; Koering et al. 2000; Bhattacharya and Warner 2008; Hogues et al. 2008). It is possible therefore that yeast CK2 (group 6, Table 5; supplemental Figure S3) acts directly upon either Tbf1 or Rap1. Alternatively, multiple interactions between CK2 subunits and genes involved in modulating chromatin architecture are known, including multiple genes identified in this study (supplemental Figure S4) and so S. cerevisiae CK2 may exert an influence on telomere function through a general effect on chromatin. A third alternative route through which CK2 might influence the cdc13-1 phenotype is its influence on checkpoint control, which was reported previously (Toczyski et al. 1997). Further studies will be required to distinguish among these possibilities.

A large group of ribosomal protein genes (group 7, Table 5; supplemental Figure S3) and a smaller number of other genes with ribosome-related function were identified as suppressors of cdc13-1. We have no clear explanation for this; however, a clue may come from the observation that chromosomal regions containing ribosomal protein genes and telomeres have similar mechanisms for regulating their chromatin architecture (Bhattacharya and Warner 2008; Hogues et al. 2008). Remarkably, this group includes 16 large ribosomal protein subunit genes but only one component of the small ribososmal subunit.

Numerous groups of genes identified in this study have not previously been linked to telomere function. Genes affecting mitochrondrial function (group 8, Table 5) (particularly those involved in electron transport and import into mitochondria), for example, are cdc13-1 suppressors when deleted. Interestingly, Nautiyal et al. (2002) showed that many mitochondrial genes are transcriptionally upregulated in telomerase-deficient mutants and we have recently found similar results in cdc13-1 mutants (A. Greenall and D. Lydall, personal communication). Furthermore, there appear to be evolutionarily conserved interactions between mitochondria and telomeres (Passos et al. 2007). Therefore, one possible explanation of why so many genes involved in mitochondrial function suppress cdc13-1 when deleted is that loss of mitochondrial function, and the ability to respire, suppresses the poor growth of cdc13-1 mutants. Indeed, we find that many petite mutants suppress the cdc13-1 defect (Table 1).

The suppression of cdc13-1 temperature sensitivity by petite mutations as a whole is interesting and warrants further investigation. We sought to test whether many other gene deletions might be suppressing cdc13-1 indirectly by causing loss of mitochondrial function. Mitochondrial function (respiration) is essential for growth on glycerol; therefore we spotted single-gene deletion strains [corresponding to all cdc13-1 suppressors (Table 1)] using glycerol as the sole carbon source. We found that only those previously described as “petite” were unable to grow on glycerol (data not shown). We also found that suppression by petite mutations is not due simply to slower growth because growth on synthetic medium does not suppress cdc13-1 temperature sensitivity and there are multiple nonpetite mutations that confer slow growth but fail to suppress cdc13-1 temperature sensitivity (data not shown). We conclude that the vast majority of cdc13-1 suppressors that we have identified are not suppressing because they disrupt mitochondrial function.

Five genes (OCA1, OCA2, OCA4, OCA6, SIW14; group 9, Tables 2 and 5; supplemental Figure S3) containing a highly conserved tyrosine phosphatase motif were identified as suppressors of cdc13-1. Little is known about their function except that OCA1 and SIW14 have roles in checkpoint response to oxidative stress and actin filament organization, respectively (Alic et al. 2001; Care et al. 2004). Suppression of cdc13-1 has been confirmed in a separate genetic background (W303) for OCA2, OCA4, OCA6, and SIW14. It was also found that OCA5, which lacks the tyrosine phosphatase motif and was not detected as a suppressor in this screen, does suppress cdc13-1 temperature sensitivity in the W303 background (Table 2). It will be interesting to determine how the OCA gene family interacts with uncapped telomeres, possibly by interacting with the checkpoint kinase cascade or perhaps by affecting telomere capping.

The partially redundant BMH1 and BMH2 genes (group 10, Table 5; supplemental Figure S3) encode 14-3-3 proteins, which bind phosphopeptides (van Heusden and Steensma 2006). It has been shown that Bmh1 and Bmh2 affect checkpoint signal transduction (Lottersberger et al. 2003, 2006, 2007) and therefore, like Rad9 and Rad24, their absence is expected to improve the growth of cdc13-1 mutants. Further experiments will be necessary to explain the roles of other groups of genes (groups 11–20, Table 5; supplemental Figure S3) in exacerbating the cdc13-1 telomere-capping defect.

UP–DOWN sensitive genes:

We classify UDS genes as those that contribute to the viability of cdc13-1 mutant cells during brief incubation periods at high temperature. Their deletion causes cdc13-1 cells to grow poorly in the UP–DOWN assay. Deletion of RAD9 suppresses the temperature sensitivity of cdc13-1, as well as rendering cdc13-1 cells sensitive to temperature oscillation (Figure 1) and we predicted that other UDS genes that similarly suppressed cdc13-1 would be identified in this screen and classed as truly “RAD9-like.” Indeed, RAD9, CHK1, DDC1, RAD17, RAD24, and other genes with DNA-repair-related roles (DOA1) were identified. However, also included were genes for cell polarity and cellular morphogenesis (ELM1, SHE4), membrane traffic (EDE1, VPS21), response to oxidative stress (UTH1), mRNA degradation (SKI3), DNA replication in meiosis (MUM2), chromatin architecture (SAS4), and cell-wall biogenesis (GAS1). SHE4 in particular is interesting since its deletion causes strong suppression (Table 1) and a strong UDS phenotype (Table 4 and data not shown). She4 is an UNC domain protein that interacts with type I and type V myosins and has roles in mating-type switching (by helping to localize the mRNA for Ash1) and endocytosis. Since other genes involved in both vesicular traffic and Ash1 function have been identified in this study, it remains to be determined through which of these pathways SHE4 exerts an influence on telomere biology.

Rather less predictable was a large number of UDS genes (81), which do not suppress cdc13-1 temperature sensitivity when deleted (Table 4, Figure 2). Deletion of some of these genes caused reduced growth during spot tests (not detected in SGA analysis; supplemental Figure S2), even at the permissive temperature of 20° (data not shown). They were classed as UDS because growth was still poor in the UP–DOWN assay relative to growth at the permissive temperature. There is a subtle distinction, therefore, between this class of genes and those that exhibit a synthetic sick interaction with cdc13-1 at temperatures >23°.

Only deletion of YME1 appeared to demonstrate both UDS (in screens 3 and 4; supplemental Table S1) and synthetic sick (in screen 7; supplemental Table S1) interactions with cdc13-1; null mutations in this mitochondrial protease have previously been shown to be pleiotropic, including exhibiting cold sensitivity on rich glucose medium (Thorsness et al. 1993). Genes such as this with apparently “variable” phenotypes were rare. However, another example is ASC1. Deletion of ASC1 has previously resulted in synthetic interactions with wild-type query strains in the SGA procedure (Tong et al. 2001; see supplemental Methods); however, we obtained viable progeny from SGA in 5 of 10 biological replicates with this gene deletion. Four of five of these demonstrated suppression of cdc13-1 and UDR so ASC1 is, tentatively, classified as a suppressor and UDR, that is, EXO1-like.

EST1, EST2, and EST3 genes encoding telomerase holoenzyme components fell into the UDS category (group 21, Table 5; supplemental Figure S4). This is almost certainly because telomerase, and its product telomeric DNA, contribute to forming the telomere cap. The absence of telomerase therefore sensitizes cdc13-1 mutants to high temperature. Conversely, deleting PIF1, which encodes a helicase that removes telomerase, suppresses the temperature sensitivity of cdc13-1 mutants.

The UDS genes included genes for both subunits of the Ku complex (YKU70 and YKU80), BRE2, and DOT1. The latter encodes the H3K79 methylase and appears to help recruit Rad9 to chromatin and, like Rad9, inhibits resection at uncapped telomeres (Lazzaro et al. 2008).

Spindle checkpoint and mitotic exit genes (groups 22 and 23, Table 5; supplemental Figure S4) also helped cdc13-1 cells to recover from shifts to high temperature, presumably because, after a period of arrest prior to entry into mitosis, the mitotic exit network is important for efficient completion of the cell cycle.

The telomere-related roles of genes involved in transposition, glycerol osmosensing, or methionine and threonine synthesis (groups 24–26, Table 5; supplemental Figure S4) remain unclear, although the former group has been implicated in chromatin remodeling.

UP–DOWN-resistant genes:

EXO1 encodes a nuclease that contributes to the vulnerability of cdc13-1 mutant cells to brief incubation periods at high temperature. A likely explanation for this is that deletion of EXO1 results in less resection and thus less DNA damage at the nonpermissive temperature, thus hastening the cells' recovery when returned to the permissive temperature (Zubko et al. 2004). We have hypothesized that other nucleases, such as a putative RAD24-dependent nuclease ExoX, also regulate resection at uncapped telomeres (Jia et al. 2004; Zubko et al. 2004). Therefore, we searched for other EXO1-like genes. Deletion of EXO1 suppresses the temperature sensitivity of cdc13-1, as well as rendering cdc13-1 cells less sensitive to temperature oscillation (Figure 1). In fact, only two genes—ASC1 and SRN2—fall into this category. ASC1 encodes a core component of the 40S ribosomal subunit, which acts as a guanine nucleotide dissociation inhibitor for Gpa2 (Zeller et al. 2007), and its deletion results in longer telomeres (Askree et al. 2004). Srn2 is a member of the ESCRT-1 endosomal sorting complex (Kostelansky et al. 2007), which targets proteins to endosomes in a ubiquitin-dependent manner. The other two subunits of this complex (Stp22 and Vps28) were in the group of slow-growing deletion strains that were not tested in this study but have been shown previously to have shorter telomeres, whereas deletion of SRN2 is not reported to affect telomere length (Askree et al. 2004; Gatbonton et al. 2006). Two other genes were UDR without being cdc13-1 suppressors: MAE1 and RVS161. RVS161 encodes an amphiphysin-like raft protein, which acts (with Rvs167) to regulate polarization of the actin cytoskeleton; thus its deletion has pleiotropic effects, which include disruption of endocytosis (Breton et al. 2001; Lombardi and Riezman 2001). MAE1 encodes a mitochondrial malic enzyme that catalyzes the oxidative decarboxylation of malate to pyruvate (Boles et al. 1998). None of the EXO1-like genes identified here are likely candidates for ExoX. Therefore, ExoX does not exist, was missing from our library, is encoded by an essential gene, or its activity is encoded by multiple, redundant genes.

Comparisons with telomere length screens:

Two previous genomewide studies of telomere biology have measured the length of telomere repeat regions in gene deletion strains (Askree et al. 2004; Gatbonton et al. 2006). Interestingly, there was less overlap than might have been expected between the two studies in terms of the specific genes identified; however, the processes that affected telomere length in each study were similar (Gatbonton et al. 2006). Comparison of our results with these two previous studies reveals moderate overlap (Figure 3) but, again, some similar cellular processes were identified.

Thirteen genes were identified in all three studies and this clearly represents an important set of telomere-related genes. Seven of these were found to support telomere capping in our study—EST1, EST2, and EST3 (encoding subunits of telomerase); YKU70 and YKU80 (encoding the Ku heterodimer); and CDC73 and DCC1—and show reduced telomere length when deleted. Deletion of ELG1 (UDS) results in longer telomeres. Deletion of PIF1 (Downey et al. 2006), which encodes a helicase that removes telomerase from telomeres, and of RIF2 (Wotton and Shore 1997), which inhibits telomerase activity, results in long telomeres and suppression of cdc13-1. Deletion of NAM7, UPF3, and NMD2, which regulate nonsense-mediated RNA decay, affecting levels of the Cdc13-interacting protein Stn1, results in strong suppression of cdc13-1 and short telomeres. Clearly, the implications of altered telomere length or genetic interaction with cdc13-1 arising from a gene deletion study are complex.

Many of the genes identified by Askree et al. (2004) or Gatbonton et al. (2006), which were not identified by our screens, are particularly poor growing strains or those previously demonstrated as working poorly in the SGA techniques (in parentheses in Figure 3; Tong et al. 2001). Conversely, there are 326 genes identified in our study as interacting with cdc13-1, which do not significantly alter telomere length. These include genes that are known to affect the response to telomere uncapping without affecting telomere length (e.g., the checkpoint genes RAD9 and CHK1). However, it also seems likely that cdc13-1 mutants are sensitive to deletion of some genes where the resulting changes in telomere length are too small to be detected using high-throughput Southern blot analysis.

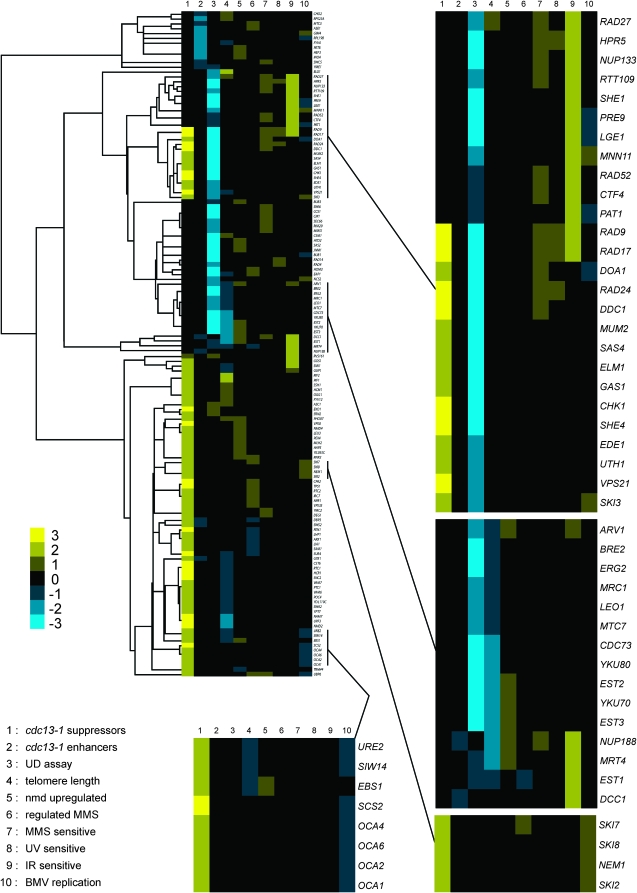

Comparisons with multiple high-throughput studies:

In addition to telomere length, multiple genomewide studies have examined processes that are relevant to telomere biology including, for example, UV irradiation (Birrell et al. 2001), ionizing radiation (Bennett et al. 2001), alkylating agents (Jelinsky and Samson 1999; Chang et al. 2002), and nonsense-mediated decay (He et al. 2003). We combined these data sets, a study of genes affecting replication of a positive-strand DNA virus (Kushner et al. 2003), and the telomere length studies (Askree et al. 2004; Gatbonton et al. 2006; Shachar et al. 2008) with our own data to produce a hierarchical clustering map (Figure 4). For two previously uncharacterized genes identified in this study, such clustering may provide clues to their putative function. For example, MTC7 lies in a cluster of genes that, when deleted, confer UP–DOWN sensitivity and short telomeres. This cluster includes telomere maintenance, histone methylation, and silencing genes (Figure 4), indicating that Mtc7 might influence telomere biology through one of these processes. RTC1 lies in a cluster of genes that, when deleted, confer suppression of cdc13-1 temperature sensitivity and short telomeres (Figure 4). This cluster includes genes involved in nonsense-mediated decay and membrane transport, indicating that Rtc1 might influence telomere biology through one of these processes.

Figure 4.—

Hierarchical clustering of cdc13-1 genetic interactions with data from multiple genomewide studies. cdc13-1 suppressor and enhancer data are combined with data from genomewide studies of telomere length, nonsense-mediated decay (nmd upregulated), the effect of MMS on gene transcriptions (regulated MMS), MMS sensitivity, UV sensitivity, ionizing radiation sensitivity (IR sensitive), and Brome mosaic virus (BMV) replication. cdc13-1 synthetic sick and synthetic lethal interactions are grouped under the heading “cdc13-1 enhancers,” separately from interactors identified in the UP–DOWN (UD) assay. Yellow and blue shading on the heat map indicate positive and negative values, respectively (as defined in the supplemental Methods). Four interesting clusters are highlighted with magnified heat maps. One of these clusters (center, right) contains the previously uncharacterized MTC7 gene, identified in this study (see discussion).

In conclusion, the budding yeast telomere cap and the response to telomere uncapping induced in cdc13-1 mutants appear to be affected by numerous and diverse cellular pathways and processes. Further analyses will be necessary to understand how these pathways and processes interact at yeast telomeres. It seems likely that a significant fraction of the pathways and processes identified in yeast will play roles at human telomeres and thereby affect cancer and/or aging.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Charlie Boone and Renee Brost for providing strains and advice on the SGA technique; Centre for Integrated Systems Biology of Ageing and Nutrition colleagues past and present (in particular, Allyson Lister for help with the Robot Object Database, Dan Swan for computer support, and Suzanne Advani for excellent technical help); Tim Humphrey for helpful suggestions regarding the manuscript; Cammie Lesser and Roger Kramer for productive discussions about spot scoring; and Sasan Raghibizadeh, Pedram Raghibizadeh, and Ewan Grant for help with robotics. This work was supported by the Wellcome Trust (075294) and the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BB/C008200/1).

References

- Alic, N., V. J. Higgins and I. W. Dawes, 2001. Identification of a Saccharomyces cerevisiae gene that is required for G1 arrest in response to the lipid oxidation product linoleic acid hydroperoxide. Mol. Biol. Cell 12 1801–1810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvaro, D., M. Lisby and R. Rothstein, 2007. Genomewide analysis of Rad52 foci reveals diverse mechanisms impacting recombination. PLoS Genet. 3 e228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Askree, S. H., T. Yehuda, S. Smolikov, R. Gurevich, J. Hawk et al., 2004. A genome-wide screen for Saccharomyces cerevisiae deletion mutants that affect telomere length. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101 8658–8663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baetz, K., V. Measday and B. Andrews, 2006. Revealing hidden relationships among yeast genes involved in chromosome segregation using systematic synthetic lethal and synthetic dosage lethal screens. Cell Cycle 5 592–595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, C. B., L. K. Lewis, G. Karthikeyan, K. S. Lobachev, Y. H. Jin et al., 2001. Genes required for ionizing radiation resistance in yeast. Nat. Genet. 29 426–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya, A., and J. R. Warner, 2008. Tbf1 or not Tbf1? Mol. Cell 29 537–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birrell, G. W., G. Giaever, A. M. Chu, R. W. Davis and J. M. Brown, 2001. A genome-wide screen in Saccharomyces cerevisiae for genes affecting UV radiation sensitivity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98 12608–12613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blasco, M. A., 2007. Telomere length, stem cells and aging. Nat. Chem. Biol. 3 640–649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boles, E., P. de Jong-Gubbels and J. T. Pronk, 1998. Identification and characterization of MAE1, the Saccharomyces cerevisiae structural gene encoding mitochondrial malic enzyme. J. Bacteriol. 180 2875–2882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breitkreutz, B. J., C. Stark and M. Tyers, 2003. Osprey: a network visualization system. Genome Biol. 4 R22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breitkreutz, B. J., C. Stark, T. Reguly, L. Boucher, A. Breitkreutz et al., 2008. The BioGRID Interaction Database: 2008 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 36 D637–D640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breton, A. M., J. Schaeffer and M. Aigle, 2001. The yeast Rvs161 and Rvs167 proteins are involved in secretory vesicles targeting the plasma membrane and in cell integrity. Yeast 18 1053–1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Care, A., K. A. Vousden, K. M. Binley, P. Radcliffe, J. Trevethick et al., 2004. A synthetic lethal screen identifies a role for the cortical actin patch/endocytosis complex in the response to nutrient deprivation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 166 707–719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang, M., M. Bellaoui, C. Boone and G. W. Brown, 2002. A genome-wide screen for methyl methanesulfonate-sensitive mutants reveals genes required for S phase progression in the presence of DNA damage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99 16934–16939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung, A. L., and W. Deng, 2008. Telomere dysfunction, genome instability and cancer. Front. Biosci. 13 2075–2090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choudhury, A. R., Z. Ju, M. W. Djojosubroto, A. Schienke, A. Lechel et al., 2007. Cdkn1a deletion improves stem cell function and lifespan of mice with dysfunctional telomeres without accelerating cancer formation. Nat. Genet. 39 99–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahlseid, J. N., J. Lew-Smith, M. J. Lelivelt, S. Enomoto, A. Ford et al., 2003. mRNAs encoding telomerase components and regulators are controlled by UPF genes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Eukaryot. Cell 2 134–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downey, M., R. Houlsworth, L. Maringele, A. Rollie, M. Brehme et al., 2006. A genome-wide screen identifies the evolutionarily conserved KEOPS complex as a telomere regulator. Cell 124 1155–1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisen, M. B., P. T. Spellman, P. O. Brown and D. Botstein, 1998. Cluster analysis and display of genome-wide expression patterns. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95 14863–14868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enomoto, S., L. Glowczewski, J. Lew-Smith and J. G. Berman, 2004. Telomere cap components influence the rate of senescence in telomerase-deficient yeast cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24 837–845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falcon, S., and R. Gentleman, 2007. Using GOstats to test gene lists for GO term association. Bioinformatics 23 257–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fourel, G., E. Revardel, C. E. Koering and E. Gilson, 1999. Cohabitation of insulators and silencing elements in yeast subtelomeric regions. EMBO J. 18 2522–2537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallardo, F., C. Olivier, A. T. Dandjinou, R. J. Wellinger and P. Chartrand, 2008. TLC1 RNA nucleo-cytoplasmic trafficking links telomerase biogenesis to its recruitment to telomeres. EMBO J. 27 748–757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner, R. G., Z. W. Nelson and D. E. Gottschling, 2005. Degradation-mediated protein quality control in the nucleus. Cell 120 803–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garvik, B., M. Carson and L. Hartwell, 1995. Single-stranded DNA arising at telomeres in cdc13 mutants may constitute a specific signal for the RAD9 checkpoint. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15 6128–6138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatbonton, T., M. Imbesi, M. Nelson, J. M. Akey, D. M. Ruderfer et al., 2006. Telomere length as a quantitative trait: genome-wide survey and genetic mapping of telomere length-control genes in yeast. PLoS Genet. 2 e35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greider, C. W., and E. H. Blackburn, 1985. Identification of a specific telomere terminal transferase activity in Tetrahymena extracts. Cell 43 405–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He, F., X. Li, P. Spatrick, R. Casillo, S. Dong et al., 2003. Genome-wide analysis of mRNAs regulated by the nonsense-mediated and 5′ to 3′ mRNA decay pathways in yeast. Mol. Cell 12 1439–1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogues, H., H. Lavoie, A. Sellam, M. Mangos, T. Roemer et al., 2008. Transcription factor substitution during the evolution of fungal ribosome regulation. Mol. Cell 29 552–562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jelinsky, S. A., and L. D. Samson, 1999. Global response of Saccharomyces cerevisiae to an alkylating agent. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96 1486–1491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia, X., T. Weinert and D. Lydall, 2004. Mec1 and Rad53 inhibit formation of single-stranded DNA at telomeres of Saccharomyces cerevisiae cdc13-1 mutants. Genetics 166 753–764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M. K., M. R. Kang, H. W. Nam, Y. S. Bae, Y. S. Kim et al., 2008. Regulation of telomeric-repeat binding factor 1 binding to telomeres by casein kinase 2-mediated phosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem. 283 14144–14152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koering, C. E., G. Fourel, E. Binet-Brasselet, T. Laroche, F. Klein et al., 2000. Identification of high affinity Tbf1p-binding sites within the budding yeast genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 28 2519–2526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostelansky, M. S., C. Schluter, Y. Y. Tam, S. Lee, R. Ghirlando et al., 2007. Molecular architecture and functional model of the complete yeast ESCRT-I heterotetramer. Cell 129 485–498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushner, D. B., B. D. Lindenbach, V. Z. Grdzelishvili, A. O. Noueiry, S. M. Paul et al., 2003. Systematic, genome-wide identification of host genes affecting replication of a positive-strand RNA virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100 15764–15769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazzaro, F., V. Sapountzi, M. Granata, A. Pellicioli, M. Vaze et al., 2008. Histone methyltransferase Dot1 and Rad9 inhibit single-stranded DNA accumulation at DSBs and uncapped telomeres. EMBO J. 27 1502–1512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lombardi, R., and H. Riezman, 2001. Rvs161p and Rvs167p, the two yeast amphiphysin homologs, function together in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 276 6016–6022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longhese, M. P., 2008. DNA damage response at functional and dysfunctional telomeres. Genes Dev. 22 125–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lottersberger, F., F. Rubert, V. Baldo, G. Lucchini and M. P. Longhese, 2003. Functions of Saccharomyces cerevisiae 14-3-3 proteins in response to DNA damage and to DNA replication stress. Genetics 165 1717–1732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lottersberger, F., A. Panza, G. Lucchini, S. Piatti and M. P. Longhese, 2006. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae 14-3-3 proteins are required for the G1/S transition, actin cytoskeleton organization and cell wall integrity. Genetics 173 661–675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lottersberger, F., A. Panza, G. Lucchini and M. P. Longhese, 2007. Functional and physical interactions between yeast 14-3-3 proteins, acetyltransferases, and deacetylases in response to DNA replication perturbations. Mol. Cell. Biol. 27 3266–3281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lydall, D., 2003. Hiding at the ends of yeast chromosomes: telomeres, nucleases and checkpoint pathways. J. Cell Sci. 116 4057–4065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maringele, L., and D. Lydall, 2002. EXO1-dependent single-stranded DNA at telomeres activates subsets of DNA damage and spindle checkpoint pathways in budding yeast yku70Delta mutants. Genes Dev. 16 1919–1933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Measday, V., K. Baetz, J. Guzzo, K. Yuen, T. Kwok et al., 2005. Systematic yeast synthetic lethal and synthetic dosage lethal screens identify genes required for chromosome segregation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102 13956–13961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nautiyal, S., J. L. DeRisi and E. H. Blackburn, 2002. The genome-wide expression response to telomerase deletion in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99 9316–9321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nugent, C. I., T. R. Hughes, N. F. Lue and V. Lundblad, 1996. Cdc13p: a single-strand telomeric DNA-binding protein with a dual role in yeast telomere maintenance. Science 274 249–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olovnikov, A. M., 1973. A theory of marginotomy. The incomplete copying of template margin in enzymic synthesis of polynucleotides and biological significance of the phenomenon. J. Theor. Biol. 41 181–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passos, J. F., G. Saretzki, S. Ahmed, G. Nelson, T. Richter et al., 2007. Mitochondrial dysfunction accounts for the stochastic heterogeneity in telomere-dependent senescence. PLoS Biol. 5 e110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polotnianka, R. M., J. Li and A. J. Lustig, 1998. The yeast Ku heterodimer is essential for protection of the telomere against nucleolytic and recombinational activities. Curr. Biol. 8 831–834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reaper, P. M., F. di Fagagna and S. P. Jackson, 2004. Activation of the DNA damage response by telomere attrition: a passage to cellular senescence. Cell Cycle 3 543–546. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rog, O., S. Smolikov, A. Krauskopf and M. Kupiec, 2005. The yeast VPS genes affect telomere length regulation. Curr. Genet. 47 18–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roguev, A., M. Wiren, J. S. Weissman and N. J. Krogan, 2007. High-throughput genetic interaction mapping in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Nat. Methods 4 861–866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saldanha, A. J., 2004. Java Treeview: extensible visualization of microarray data. Bioinformatics 20 3246–3248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandell, L. L., and V. A. Zakian, 1993. Loss of a yeast telomere: arrest, recovery, and chromosome loss. Cell 75 729–739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaetzlein, S., N. R. Kodandaramireddy, Z. Ju, A. Lechel, A. Stepczynska et al., 2007. Exonuclease-1 deletion impairs DNA damage signaling and prolongs lifespan of telomere-dysfunctional mice. Cell 130 863–877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saccharomyces Genome Database, 2008. Saccharomyces Genome Database. http://www.yeastgenome.org.

- Shachar, R., L. Ungar, M. Kupiec, E. Ruppin and R. Sharan, 2008. A systems-level approach to mapping the telomere length maintenance gene circuitry. Mol. Syst. Biol. 4 172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stark, C., B. J. Breitkreutz, T. Reguly, L. Boucher, A. Breitkreutz et al., 2006. BioGRID: a general repository for interaction datasets. Nucleic Acids Res. 34 D535–D539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira, M. T., K. Forstemann, S. M. Gasser and J. Lingner, 2002. Intracellular trafficking of yeast telomerase components. EMBO Rep. 3 652–659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorsness, P. E., K. H. White and T. D. Fox, 1993. Inactivation of YME1, a member of the ftsH-SEC18-PAS1-CDC48 family of putative ATPase-encoding genes, causes increased escape of DNA from mitochondria in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 13 5418–5426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toczyski, D. P., D. J. Galgoczy and L. H. Hartwell, 1997. CDC5 and CKII control adaptation to the yeast DNA damage checkpoint. Cell 90 1097–1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong, A. H., and C. Boone, 2006. Synthetic genetic array analysis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Methods Mol. Biol. 313 171–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong, A. H., M. Evangelista, A. B. Parsons, H. Xu, G. D. Bader et al., 2001. Systematic genetic analysis with ordered arrays of yeast deletion mutants. Science 294 2364–2368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Heusden, G. P., and H. Y. Steensma, 2006. Yeast 14-3-3 proteins. Yeast 23 159–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinert, T. A., G. L. Kiser and L. H. Hartwell, 1994. Mitotic checkpoint genes in budding yeast and the dependence of mitosis on DNA replication and repair. Genes Dev. 8 652–665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wotton, D., and D. Shore, 1997. A novel Rap1p-interacting factor, Rif2p, cooperates with Rif1p to regulate telomere length in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes Dev. 11 748–760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]