Abstract

Conversion of a failed surface hip replacement to a conventional total hip arthroplasty is reportedly a straightforward procedure with excellent results. We compared perioperative parameters, complications, and clinical as well as radiographic outcomes of 39 hemi and total hip resurfacing conversions with conventional THAs. The hips were matched by diagnosis, gender, age, body mass index, preoperative Harris hip score, and followup time to a cohort of primary conventional THAs performed during the same time period by the same surgeon. The mean operative time was longer (by 19 minutes) for the conversions, but other perioperative parameters were similar. At a mean followup of 45 months (range, 24–63 months), the mean Harris hip scores were similar in the two groups (92 points versus 94 points for the conversion and conventional hips, respectively). Thirty-eight of 39 stems were well-aligned and appeared osseointegrated. When a resurfaced hip fails, conversion to conventional THA has similar early clinical and radiographic outcomes to primary conventional THA.

Level of Evidence: Level III, therapeutic (retrospective comparative study). See the Guidelines for Authors for a complete description of levels of evidence.

Introduction

Metal-on-metal total hip resurfacing arthroplasty has recently emerged as an alternative to conventional total hip arthroplasty in treating osteoarthritis of the hip. Some potential advantages of resurfacing include preservation of bone of the femoral head and neck, decreased stress shielding of the proximal femur, and reduced rates of hip dislocation [2, 16, 25, 26]. A number of recent short- and mid-term reports describe early successes of this procedure [2, 3, 6, 14, 16, 18, 22, 26].

Hemiresurfacing has been utilized for over 20 years for treating osteonecrosis of the femoral head when the acetabular cartilage is in good condition [7, 13, 17, 21, 24]. It has led to good short-term clinical outcomes comparable to conventional total hip arthroplasty (THA), although some authors report mixed outcomes [1, 7, 8, 10, 13, 17, 20]. However, it is generally viewed as a temporizing procedure that ultimately would need conversion to a THA when the acetabular cartilage is affected by wear [7, 13]. For this reason, hemiresurfacing was used primarily for young patients who would otherwise need a THA, potentially followed by one or more subsequent revisions in their lifetime [1, 7, 8, 10, 13, 17, 20]. However, metal-on-metal total hip resurfacing might be a better solution than hemiresurfacing because it might avoid possible failures from acetabular cartilage wear.

The preservation of proximal femoral bone is an important aspect of resurfacing because it might allow for straightforward revision to a standard THA if the resurfaced hip fails. The most common reasons for failure of resurfacings include aseptic loosening of the femoral component and fracture of the femoral neck [3, 5, 16, 23]. As previously stated, degeneration of the acetabular cartilage is the most frequent cause of failure of hemiresurfacing arthroplasties [10, 13, 17]. In either case, it is believed the femoral neck can be removed and a conventional stem placed without difficulty. The acetabular component can be left intact if stable and undamaged, or a new cup can be placed. Limited data suggest the clinical and radiographic outcomes of these revisions are similar to the outcomes of primary THAs [1, 2, 5, 8, 13]. However, only one study [5] has directly compared these two procedures. That report concluded that operative durations, estimated blood losses, postoperative Harris hip scores, and radiographic alignments of 21 patients who underwent conversions were similar to an unmatched group of patients who underwent primary THAs at a mean followup of 46 months.

The present study was undertaken to compare a larger group of patients who underwent conversions with a well-matched group of patients who underwent primary THAs. We specifically compared operative times, estimated blood losses, Harris hip scores, ranges of motion, radiographic alignments and radiolucencies, as well as complications. We also described various techniques for converting failed surface replacements to THAs.

Materials and Methods

We compared the outcomes of 34 consecutive patients (39 hips) who had surface replacement arthroplasties converted to conventional total hip replacements with the outcomes of a matched group of 34 patients (39 hips) who had primary conventional THAs performed by the same surgeon (MAM) between November 2000 and June 2005. Twenty-one of the patients who underwent conversions (23 hips) had metal-on-metal total hip resurfacing arthroplasties and 13 (16 hips) had hemiresurfacing arthroplasties. These were from a total of 510 total hip resurfacings and 602 hemiresurfacing arthroplasties that had been performed by this author between 1997 and 2005. The patients who received total hip resurfacing arthroplasties were part of an FDA Investigational Device Exemption prospective cohort and the patients who underwent hemiresurfacing were prospectively followed. All consecutive patients who underwent conversion from a failed femoral head resurfacing to a conventional THA stem, with or without acetabular revision, were included in this study. We excluded two patients who underwent revision of the acetabular component only leaving the resurfaced femoral head intact. Most of the conversions (17 of the 23 total hip resurfacing and all of the hemiresurfacing conversions) occurred in patients who were among the first 70 resurfacing procedures performed by this surgeon, and the percentage of failures has been less than 0.5% since the indications and techniques for resurfacing have been modified [15, 19]. The patients who underwent conversions were matched to a cohort of patients who had undergone primary conventional THA during the same time period by the same surgeon. Perioperative times, estimated blood losses, complications, and postoperative parameters (Harris hip scores, ranges of motion, and radiographic outcomes) of the two groups were compared. This study had full institutional review board approval.

The patients who underwent conversions consisted of 20 men and 14 women who had a mean age of 44 years (range, 24–72 years) at the time of revision, and a mean body mass index of 30 (range, 16–50) kg/m2. The mean length of time between resurfacing arthroplasty and revision was 21 months (range, 0–60 months). Additional demographic variables and reasons for conversions were also recorded (Tables 1, 2). During the same time period, two additional patients who had received surface replacements underwent isolated acetabular cup revisions by the senior author for loosening of the acetabular components, and one patient who had undergone resurfacing underwent open reduction and internal fixation of the proximal femur with a dynamic hip screw for an intertrochanteric fracture. These three patients were not included in the present study because their femoral resurfacing components were not converted to conventional stems. The minimum followup time was 24 months (mean, 45 months; range, 24–63 months).

Table 1.

Demographic and preoperative variables of the conversion patients and the matched conventional total hip arthroplasty patients

| Variable | Conversion cohort | Matched cohort |

|---|---|---|

| Number of patients (hips) | 34 (39) | 34 (39) |

| Men | 20 (22) | 20 (22) |

| Women | 14 (17) | 14 (17) |

| Diagnosis—number of patients (hips) | ||

| Osteoarthritis | 18 (20) | 18 (20) |

| Osteonecrosis | 16 (19) | 16 (19) |

| Mean age in years (range) | 44 (24–72) | 44 (24–70) |

| Mean body mass index in kg/m2 (range) | 29.8 (16.3–49.6) | 29.5 (19.6–49.6) |

| Mean preoperative Harris hip score in points (range) | 40 (5–65) | 45 (8–67) |

| Mean length of time between resurfacing and conversion in months (range) | 21 (0–60) | Not applicable |

Table 2.

Reasons for conversion of resurfaced hips to conventional total hip arthroplasties and the type of conversion performed

| Classification | Number of patients (hips) |

|---|---|

| Femoral neck fracture | 16 (17) |

| Converted to conventional stem with big femoral head, cup left intact | 11 (12) |

| Femoral and acetabular components both converted to conventional stem and cup | 5 (5) |

| Femoral component loosening | 3 (4) |

| Converted to conventional stem with big femoral head, cup left intact | |

| Infection | 2 (2) |

| Two-stage revision to conventional stem and head | |

| Deterioration of acetabular cartilage in hemiresurfacing | 13 (16) |

| Converted to conventional stem and head, cup placed | 9 (11) |

| Converted to conventional stem with big femoral head, cup placed | 4 (4) |

The 34 patients who had undergone conversions (39 hips) were matched to 34 patients (39 hips) from a prospectively followed cohort of patients who had primary conventional THAs performed by the same surgeon during the same time period. Patients were directly matched by diagnosis, gender, age, body mass index, preoperative Harris hip score, and length of followup. Further preoperative and demographic data for the matched cohort of patients were also recorded (Table 1). A post-hoc power analysis to determine the power of the present study was performed. With the Harris hip score as the primary outcome, an effect size of 0.5, and a standard deviation of 6, the 39 hips in each group were associated with a power of 0.99 at an alpha of 0.05.

All surgeries were performed by the senior author (MAM) using an anterolateral approach. The original resurfacing procedures utilized Conserve Plus™ components and instruments (Wright Medical Technology, Arlington, TN). All femoral components were cemented and all acetabular components utilized press-fit fixation. In 16 of the 23 total resurfacing arthroplasty conversions, the resurfacing acetabular component was left in place and a Perfecta™ proximally porous-coated stem (Wright Medical Technology, Arlington, TN) was utilized with a large-diameter femoral head to match the acetabular component. In three of the conversions, large femoral heads matching the resurfacing cups were not available, so the hips were converted to conventional stems and heads, with acetabular revisions. In two other cases, the cup was loose, so it was revised with screw fixation in addition to implanting a conventional stem. For all of the failed hemiresurfacing arthroplasties, the femoral component was converted to a conventional stem and an acetabular cup was placed. All conversions that involved placement of a new femoral stem and acetabular cup utilized an Accolade™ proximally porous-coated, tapered stem with a Trident™ acetabular cup (Stryker, Mahwah, NJ). Those components were also used in all primary THA procedures in the matching cohort. All conventional stems and cups utilized press-fit fixation.

Prophylactic anticoagulation began the day of the operation and continued for 30 days. Mechanical lower extremity compression devices were also used during hospitalization. Patients were allowed 50% weight bearing for the first 5 postoperative weeks using a cane, crutch(es), or a walker. They were then advanced to full weight bearing as tolerated and were encouraged to continue hip strengthening exercises three times per week for life.

The estimated blood loss, time of incision, time of closure, and intraoperative complications were recorded during each surgery. Duration of surgery was calculated as the total time from incision to closure. Length of hospital stay was also recorded.

Patients were clinically evaluated by three of the authors (MAM, MSM, SDU) at 6 weeks, 6 months, 1 year, and annually thereafter. They also returned as needed for any concerns or complications. Ranges of motion were measured and recorded at each visit. Pain and function were also evaluated using the Harris hip scoring system [12].

Standard anteroposterior and cross-table lateral radiographs were obtained at each clinic visit and evaluated by three of the authors (MSM, SDU, MAM). Acetabular radiolucencies were evaluated and classified according to the DeLee and Charnley zones [9]. All radiolucent lines longer or wider than 1 mm were recorded. The stem angle was recorded and classified as neutral, varus, or valgus. A stem angle was considered neutral if its axis was within 2° of the femoral shaft axis.

We compared perioperative variables (operative time and estimated blood loss) and outcome measures (Harris hip scores) of the two matched study groups using paired Student t-tests. Both groups met the parametric assumptions of normality, equal variance, and independence. We then stratified the patients by gender, age (less than or greater than 50 years), body mass index (less than or greater than 30 kg/m2), and original procedure performed (metal-on-metal total hip resurfacing or hemiresurfacing) to evaluate the effects of these factors on the same perioperative variables as well as clinical and radiographic outcomes. Student t-tests were performed to evaluate the differences between the stratified groups. All analyses were performed with SPSS version 13.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL).

Results

The perioperative values of the two cohorts were similar (Table 3), with the exception of the mean operative times, which were greater (p = 0.028) for the conversions (mean, 142 minutes; range, 75–238 minutes) than for the matched cohort (mean, 123 minutes; range, 73–222 minutes). The mean estimated blood loss and hospital stay of the two matched cohorts were similar. Estimated blood loss was higher (p = 0.002) for the patients who originally had total hip resurfacing arthroplasties compared with the patients who had hemiresurfacings and was higher (p = 0.098) for the patients who had acetabular revisions than for the patients who had only the femoral components revised. However, we found no other differences among stratified variables.

Table 3.

Mean intraoperative and clinical function values stratified by gender, body mass index, age, and prior surgery

| Categories | Duration of surgery in minutes (range) | Estimated blood loss in mL (range) | Hospital stay in days (range) | Harris hip score in points (range) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conversion cohort | 142 (75–238) | 751 (250–2000) | 3.2 (2–5) | 92 (74–100) |

| Matched cohort | 123 (73–222) | 670 (200–1300) | 3.4 (2–6) | 94 (74–100) |

| p value | 0.028 | 0.253 | 0.378 | 0.250 |

| Male | 147 (102–238) | 790 (300–2000) | 3.1 (2–4) | 95 (81–100) |

| Female | 134 (75–210) | 692 (250–1200) | 3.4 (3–5) | 88 (70–98) |

| p value | 0.349 | 0.449 | 0.487 | 0.001 |

| BMI < 30 kg/m2 | 142 (78–238) | 747 (250–2000) | 3.2 (2–4) | 93 (75–100) |

| BMI > 30 kg/m2 | 141 (85–210) | 757 (300–1500) | 3.3 (3–5) | 91 (74–100) |

| p value | 0.927 | 0.84 | 0.797 | 0.332 |

| Age < 50 years | 145 (85–210) | 691 (300–1500) | 3.2 (2–5) | 92 (74–100) |

| Age > 50 years | 135 (75–238) | 922 (250–2000) | 3.2 (3–4) | 91 (82–100) |

| p value | 0.524 | 0.206 | 0.859 | 0.439 |

| Total | 152 (75–238) | 931 (250–2000) | 3.4 (3–5) | 92 (81–100) |

| Hemi | 132 (85–205) | 561 (300–800) | 3.1 (2–4) | 93 (74–100) |

| p value | 0.152 | 0.002 | 0.190 | 0.291 |

BMI = body mass index; Total = metal-on-metal total hip resurfacing arthroplasty; Hemi = hemiresurfacing arthroplasty.

At final followup, the patients who underwent conversions and their matched cohorts had similar clinical outcomes. The mean Harris hip scores were 92 points (range, 70–100 points) for the patients who underwent conversions and 94 points (range, 74–100 points) for the patients who underwent primary THAs (p = 0.250). Thirty-seven of 39 (95%) converted hips and 38 of 39 (97%) primary THA hips had Harris hip scores greater than 80 points. Mean range of motion scores for the conversion and matched groups were 4.9 points (range, 3.6–5 points) and 4.8 points (range, 3.6–5 points), respectively (p = 0.690). Men had a higher (p = 0.001) mean Harris hip score than women (mean, 95 points, range, 81–100 points versus mean 88 points, range, 70–98 points). We identified no other differences in functional outcomes among any of the other stratified variables (Table 3).

Two patients who underwent conversions and one patient who was in the matched cohort had Harris hip scores that were below 80 points at final followup. The patients in the conversion group who had low Harris hip scores consisted of a 23-year-old woman who began experiencing pain in her converted hip 4 years after the conversion, likely due to overuse because her contralateral hip recently collapsed secondary to osteonecrosis; and a 27-year-old woman who had progressive radiolucencies around the femoral stem 1 year after her conversion. The patient in the matched cohort who had a low Harris hip score was a 25-year-old man who had a body mass index of 50 kg/m2, and his difficulty with ambulation and stairs was likely due to obesity, as his components were well-fixed radiographically. The Harris hip scores of these patients were 70, 74, and 74 points at followup times of 56, 40, and 42 months, respectively.

All stems were in neutral radiographic alignment. Radiographs showed one loosened femoral stem observed at approximately 1 year postoperatively in a 27-year-old woman who had undergone a conversion, as described previously, but no other radiographic failures. All other radiographs were free of progressive radiolucent lines, and all other stems were integrated into bone.

Two complications occurred in the patients who underwent conversions. One patient, a 32-year-old woman who had osteonecrosis secondary to chronic corticosteroid use, developed a peroneal nerve palsy and underwent operative release. She is now asymptomatic and moving the extremity through a full range of motion, with a Harris hip score of 98 points at a followup time of 38 months. Another patient who received a conversion, a 40-year-old man who had osteonecrosis secondary to HIV infection, experienced a dislocation of his revised hip 2 months after the conversion when he was flexing and internally rotating the joint while exiting his car. The hip was reduced in the emergency room, and this patient was doing well at a followup time of 24 months with a Harris hip score of 98 points.

Discussion

Hemiresurfacing arthroplasty has been in use for over 20 years to treat osteonecrosis of the femoral head refractory to conservative treatment. The success rate has been variable, ranging from 62% to 91% at 3 years and decreasing to 45% by 15 years [1, 7, 8, 10, 13, 17]. Metal-on-metal hip resurfacing arthroplasty has recently emerged as a new treatment option for osteoarthritis and osteonecrosis over the past 10 years, especially in younger, active patients [4, 11, 16]. These prostheses have had high success rates of up to 98% at 5 years [2, 3, 6, 18, 22, 26]. However, resurfacing hip arthroplasties occasionally fail for reasons that include femoral neck fracture, component loosening, infection, and recurrent pain [2, 5, 16]. It is important to have an appropriate option available when failure of either hemiresurfacing or metal-on-metal total hip resurfacing arthroplasty occurs. One theoretical advantage of resurfacing is that the femoral head is preserved, which purportedly allows for straightforward conversion to a conventional THA [2, 16, 23]. However, few studies have assessed this. Therefore we compared the perioperative parameters as well as the functional and clinical outcomes of resurfacing conversions and primary conventional THAs.

This study had several limitations, including the small sample size and the short mean followup time of 44 months. Additionally, the two groups were not randomized, although the patients who underwent conversions were a consecutive, unselected cohort, and they were matched by several demographic and preoperative parameters to a prospectively followed cohort of patients who underwent THAs to minimize confounding factors. The sample size was limited by the number of patients who had received surface replacements at our institution and who eventually required conversions. Despite these limitations, the results do show that conversion of a resurfaced hip to a conventional THA was a straightforward procedure and that the clinical as well as radiographic results were similar to primary conventional THAs.

The perioperative variables and outcomes of the present study are similar to the four published reports [5, 7, 8, 13] that examined conversions of failed resurfacing arthroplasties in small groups of patients. Ball et al. [5] retrospectively compared 21 total hip resurfacing conversions with 64 primary THAs at a mean followup time of 46 months. The mean duration of surgery and estimated blood loss was similar for the conversions and the THAs (178 minutes versus 169 minutes, and 509 mL versus 578 mL, respectively). The mean Harris hip scores were similar at final followup (92 and 90 points, respectively). Additionally, all of the conversion patients had Harris hip scores classified as good or excellent at final followup. Hungerford et al. [13] assessed 13 hemiresurfacing patients who obtained conversions to conventional THAs. At a mean followup time of 30 months, all Harris hip scores were greater than 80 points and no complications were noted. Cuckler et al. [8] reported a mean Harris hip score of 94 points 1 year after conversions of six hemiresurfacing arthroplasties. Beaulé et al. [7] assessed eight hemiresurfacing patients who were converted to conventional THAs and three hemiresurfacing patients who were converted to total hip resurfacing arthroplasties. At a mean followup time of 46 months, the mean UCLA hip scores were 9, 10, 10, and 8 points for pain, walking, function, and activity, respectively. The only complication reported in that study [7] was a hip dislocation in a patient who was converted to a conventional THA. These results, while limited by small groups and the lack of well-matched comparison groups, are comparable to the present study, which reported a slightly longer surgical time for conversions than for primary THAs, but otherwise found similar blood loss as well as functional and radiographic outcomes, and showed that 95% of the patients who underwent conversions had Harris hip scores greater than 80 points. Our study confirms the conclusions of the previous authors by examining a larger cohort of patients, including total resurfacing as well as hemiresurfacing conversions, and comparing the results to a conventional THA cohort that was closely matched (by age, gender, original diagnosis, body mass index, preoperative Harris hip score, and followup duration).

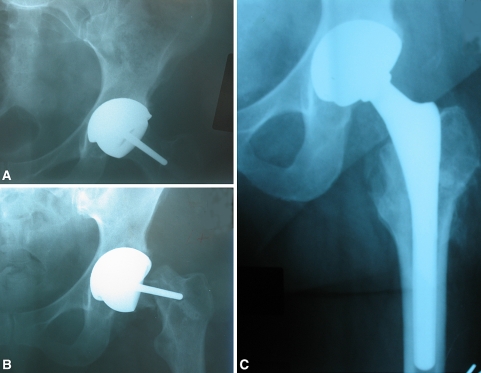

Several treatment options exist when a hip surface replacement fails. If a partially resurfaced hip develops arthritic changes of the acetabulum, it can be converted to a metal-on-metal total resurfacing arthroplasty by placing an acetabular component that matches the femoral component, or it can be converted to a conventional THA. If the femoral component of a total hip resurfacing arthroplasty fails, and the acetabular component remains intact, the femoral neck can be removed and a stem can be placed with a large femoral head that matches the acetabular component. If a large femoral head component is unavailable and the acetabular component is well-fixed, a liner can be cemented to the acetabular component and the femoral component can be revised to a conventional stem with a conventional femoral head. If the acetabular component of a total resurfacing arthroplasty has loosened or protruded, the hip can be converted to a THA with conventional components. All of these procedures are straightforward because the femoral neck can be removed inferior to the stem of the resurfacing femoral component without prolonged stem extrication or excessive bone loss (Fig. 1A–C).

Fig. 1A–C.

Anteroposterior radiographs of a 52-year-old woman who underwent a metal-on-metal total hip resurfacing procedure on her left hip for the treatment of osteoarthritis. These radiographs were taken (A) in the recovery unit shortly after the resurfacing procedure, (B) 1 month later, after the patient had fallen and endured a femoral neck fracture, and (C) 1 year after her conversion to a conventional total hip arthroplasty with a large femoral head.

With advances in metallurgy and improved designs, metal-on-metal total hip resurfacing arthroplasty is being viewed as an alternative to conventional THA. As a consequence of the increasing number of resurfacing procedures being performed, failures of resurfaced hips may occur, and thus it is important to analyze salvage procedures such as conversions to THAs. Such conversions are believed straightforward because of the bone-preserving characteristic of resurfacing. We demonstrated that a failed hip resurfacing arthroplasty could be converted to a conventional THA by various straightforward methods with perioperative as well as clinical and radiographic results similar to the results of primary THA. The operative time of the revision group was longer by a mean of 19 minutes, but this is likely due to the time necessary to address scar tissue, assess the remaining femoral as well as acetabular bone, and revise the acetabular component in some cases. These conversions had a high success rate (95%) at early followup, and further evaluation will be necessary to determine the long-term outcomes.

Footnotes

One of the authors (MAM) is a consultant for and has received financial support from Stryker Orthopaedics (Mahwah, NJ) and Wright Medical Technology (Arlington, TN). The other authors certify that he or she has no commercial associations (eg, consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements, etc) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

Each author certifies that his institution has approved the human protocol for this investigation and that all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research.

References

- 1.Adili A, Trousdale RT. Femoral head resurfacing for the treatment of osteonecrosis in the young patient. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003;417:93–101. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Amstutz HC, Ball ST, Le Duff MJ, Dorey FJ. Resurfacing THA for patients younger than 50 year: results of 2- to 9-year followup. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;460:159–164. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Amstutz HC, Beaulé PE, Dorey FJ, Le Duff MJ, Campbell PA, Gruen TA. Metal-on-metal hybrid surface arthroplasty: two to six-year follow-up study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86-A:28–39. [PubMed]

- 4.Amstutz HC, Grigoris P, Dorey FJ. Evolution and future of surface replacement of the hip. J Orthop Sci. 1998;3:169–186. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Ball ST, Le Duff MJ, Amstutz HC. Early results of conversion of a failed femoral component in hip resurfacing arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:735–741. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Beaulé PE, Le Duff M, Campbell P, Dorey FJ, Park SH, Amstutz HC. Metal-on-metal surface arthroplasty with a cemented femoral component: a 7–10 year follow-up study. J Arthroplasty. 2004;19:17–22. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Beaulé PE, Schmalzried TP, Campbell P, Dorey F, Amstutz HC. Duration of symptoms and outcome of hemiresurfacing for hip osteonecrosis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001;385:104–117. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Cuckler JM, Moore KD, Estrada L. Outcome of hemiresurfacing in osteonecrosis of the femoral head. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;429:146–150. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.DeLee JG, Charnley J. Radiological demarcation of cemented sockets in total hip replacement. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1976;121:20–32. [PubMed]

- 10.Grecula MJ. Resurfacing arthroplasty in osteonecrosis of the hip. Orthop Clin North Am. 2005;36:231–242. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Grigoris P, Roberts P, Panousis K, Jin Z. Hip resurfacing arthroplasty: the evolution of contemporary designs. Proc Inst Mech Eng [H]. 2006;220:95–105. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Harris WH. Traumatic arthritis of the hip after dislocation and acetabular fractures: treatment by mold arthroplasty. An end-result study using a new method of result evaluation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1969;51:737–755. [PubMed]

- 13.Hungerford MW, Mont MA, Scott R, Fiore C, Hungerford DS, Krackow KA. Surface replacement hemiarthroplasty for the treatment of osteonecrosis of the femoral head. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1998;80:1656–1664. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.MacDonald SJ. Metal-on-metal total hip arthroplasty: the concerns. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;429:86–93. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Marker DR, Seyler TM, Jinnah RH, Delanois RE, Ulrich SD, Mont MA. Femoral neck fractures after metal-on-metal total hip resurfacing: a prospective cohort study. J Arthroplasty. 2007;22:66–71. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Mont MA, Ragland PS, Etienne G, Seyler TM, Schmalzried TP. Hip resurfacing arthroplasty. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2006;14:454–463. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Mont MA, Rajadhyaksha AD, Hungerford DS. Outcomes of limited femoral resurfacing arthroplasty compared with total hip arthroplasty for osteonecrosis of the femoral head. J Arthroplasty. 2001;16:134–139. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Mont MA, Seyler TM, Marker DR, Marulanda GA, Delanois RE. Use of metal-on-metal total hip resurfacing for the treatment of osteonecrosis of the femoral head. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88 suppl 3:90–97. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Mont MA, Seyler TM, Ulrich SD, Beaule PE, Boyd HS, Grecula MJ, Goldberg VM, Kennedy WR, Marker DR, Schmalzried TP, Sparling EA, Vail TP, Amstutz HC. Effect of changing indications and techniques on total hip resurfacing. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;465:63–70. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Nelson CL, Garrison RL, Walz BH, McLaren SG. Resurfacing of only the femoral head—treatment for young patients with osteonecrosis of the femoral head with collapse, delamination and significant head involvement. J Ark Med Soc. 2003;100:162–163. [PubMed]

- 21.Nelson CL, Walz BH, Gruenwald JM. Resurfacing of only the femoral head for osteonecrosis. Long-term follow-up study. J Arthroplasty. 1997;12:736–740. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Pollard TC, Baker RP, Eastaugh-Waring SJ, Bannister GC. Treatment of the young active patient with osteoarthritis of the hip. A five- to seven-year comparison of hybrid total hip arthroplasty and metal-on-metal resurfacing. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2006;88:592–600. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Schmalzried TP. Total resurfacing for osteonecrosis of the hip. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;429:151–156. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Scott RD, Urse JS, Schmidt R, Bierbaum BE. Use of TARA hemiarthroplasty in advanced osteonecrosis. J Arthroplasty. 1987;2:225–232. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Silva M, Lee KH, Heisel C, Dela Rosa MA, Schmalzried TP. The biomechanical results of total hip resurfacing arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86:40–46. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Vail TP, Mina CA, Yergler JD, Pietrobon R. Metal-on-metal hip resurfacing compares favorably with THA at 2 years followup. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;453:123–131. [DOI] [PubMed]