Abstract

The most common method to diagnose and monitor osteolysis is the standard anteroposterior radiograph. Unfortunately, plain radiographs underestimate the incidence and extent of osteolysis. CT scans are more sensitive and accurate but also more expensive and subject patients to more radiation. To determine whether the volume of pelvic osteolysis could be accurately estimated without a CT scan, we evaluated the relationships between CT volume measurements and other variables that may be related to the size of pelvic osteolytic lesions in 78 THAs. Only the area of pelvic osteolysis measured on radiographs, heavy patient activity level, and total volume of wear were associated with the pelvic osteolysis volume measured on CT in the context of the multivariate regression analysis. Despite a strong correlation (r = 0.93, r2 = 0.87) between these three variables and the volume of pelvic osteolysis measured on CT, estimates of pelvic osteolysis volume deviated from the actual volume measured on CT by more than 10 cm3 among eight of the 78 THAs in this study. CT images remain our preferred modality when accurate assessments of pelvic osteolysis volume are required.

Level of Evidence: Level III, diagnostic study. See Guidelines for Authors for a complete description of levels of evidence.

Introduction

Periprosthetic osteolysis adjacent to an acetabular cup is typically asymptomatic. With time, it can contribute to cup loosening and acetabular fracture [1, 4, 10, 22]. Osteolysis can also increase the complexity and compromise the effectiveness of revision surgery [2]. Currently, the most common method in clinical practice to diagnose and monitor the progression of osteolysis is the standard anteroposterior (AP) pelvic radiograph, occasionally in concert with other views. These radiographs can be used to measure polyethylene wear and the 2-D area of osteolytic lesions. Unfortunately, plain radiographs tend to underestimate the incidence and extent of osteolysis [5, 14, 16, 21, 25]. Lytic lesions in front of or behind the acetabular implant relative to the xray beam source can be obscured by the prosthesis. The 2-D nature of plain radiographs also makes it impossible to directly assess the volume of an osteolytic lesion or the total surface area of the cup that has lost bony contact.

Clinical studies using conventional radiographs have demonstrated patients with high polyethylene wear rates are prone to develop osteolysis [6, 18–20]. However, similar studies using 3-D CT methods have yielded conflicting results. Looney et al. [16] and Howie et al. [11] reported periacetabular osteolytic volume correlated directly with polyethylene wear. In contrast, Puri et al. [21] found no correlation between osteolytic volume and linear polyethylene wear.

Stulberg et al. [25] has recommended CT as part of an algorithm for evaluating the presence and extent of osteolysis based on age, activity level, wear, and presence of osteolysis on standard radiographs. Having observed in our own clinical practice that not all patients with high wear developed radiographic evidence of osteolysis and not all patients with low wear are free of this complication, and taking into account the underestimation of pelvic osteolysis on standard radiographs, we have routinely recommended CT scans of our THA patients after the fifth postoperative year. CT scans, however, are over 10 times more expensive than an AP pelvis combined with an iliac oblique, require more sophisticated analysis techniques to interpret, and subject patients to over 10 times the radiation of an AP pelvic radiograph. Although the radiation exposure associated with a pelvic CT is considered minimal, it is equivalent to several years of exposure to natural background radiation [24, 27]. Therefore, more investigation is needed to elucidate the role of routine CT scans after total hip arthroplasty.

We hypothesized large osteolytic lesions could be reliably detected on radiographs and that other radiographic, patient- and implant-related factors could be used to accurately calculate the lesion volume in the absence of a CT scan.

Materials and Methods

We analyzed data prospectively collected and stored in our database coupled with a retrospective analysis of routine radiographs and CT scans. The study population was identified by querying our institutional database for all patients with a Duraloc® 100 cup, a porous-coated stem, and a conventional Enduron™ polyethylene liner (DePuy Orthopaedics, Warsaw, IN). A CT scan at least 5 years after surgery and a followup AP radiograph within 3 months of the CT scan were also required as study inclusion criteria. CT images had to be of sufficient quality to enable the assessment of pelvic osteolytic lesions. Radiographs had to be of sufficient quality to assess both pelvic and femoral osteolysis. To measure polyethylene wear, we further restricted the study population to cases with at least three annual followup AP pelvic radiographs (in addition to an immediate postoperative radiograph nominally taken 6 weeks after surgery) with a minimum of 2.5 years between the first and final followup radiographs. The presence or absence of osteolysis was not a selection criterion for this study. The database supplied all patient demographics (Table 1) and implant characteristics (Table 2). Radiographic factors (Table 3) and CT data were obtained by three independent reviewers as subsequently described. The mean time interval between surgery and the CT scan for the 78 hips (71 patients) that comprised the study population was 7.7 ± 2.2 years (range, 5–14.4 years). We had prior IRB approval for our study.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Female | 42 |

| Male | 36 |

| Preoperative diagnosis | |

| Osteoarthritis | 62 |

| Osteonecrosis | 11 |

| Developmental hip dysplasia | 2 |

| Posttraumatic arthrosis | 2 |

| Inflammatory arthritis | 1 |

| Age at surgery (years)* | 57.5 ± 12.2 (36–92) |

| Height (m)* | 1.71 ± 0.099 (1.52–1.93) |

| Weight (kg)* | 79.9 ± 17.1 (49.4–147.4) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2)* | 27.3 ± 5 (19.3–48.5) |

| Physician-assessed activity level | |

| Heavy | 14 |

| Moderate | 46 |

| Light | 13 |

| Semisedentary | 5 |

* For continuous variables, the data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation, with range in parentheses.

Table 2.

Implant characteristics

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Duraloc® 100 cup design | 78 |

| Enduron™ polyethylene liner material | 78 |

| Polyethylene liner geometry | |

| 4 mm lateralized | 62 |

| Standard | 13 |

| 10° lip | 3 |

| Terminal sterilization | |

| Gas plasma | 63 |

| Gamma-in-air standard dose | 11 |

| Gamma-barrier standard dose | 3 |

| Gamma-barrier low dose | 1 |

| Shelf storage duration (years) for 11 gamma-in-air sterilized liners* | 1.5 ± 1.5 (0.05–4.9) |

| Femoral head material | |

| Cobalt-chrome | 70 |

| Ceramic | 8 |

| Femoral head diameter | |

| 32 mm | 3 |

| 28 mm | 71 |

| 26 mm | 3 |

| 22 mm | 1 |

| Cup outer diameter | |

| 48 mm | 2 |

| 50 mm | 1 |

| 52 mm | 19 |

| 54 mm | 18 |

| 56 mm | 15 |

| 58 mm | 15 |

| 60 mm | 5 |

| 62 mm | 1 |

| 64 mm | 2 |

| Hole eliminator | |

| Plug with positive stop | 54 |

| Plug without positive stop | 15 |

| Not used | 9 |

| Porous-coated stem fixation | 78 |

* For continuous variables, the data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation, with range in parentheses.

Table 3.

Radiographic parameters

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Time between surgery and CT (years) | 7.7 ± 2.2 (5–14.4) |

| Volumetric wear (cm3) | 1.04 ± 0.66 (−0.33–2.58) |

| Volumetric wear rate (cm3/year) | 0.136 ± 0.082 (−0.051–0.335) |

| Linear wear (mm) | 1.86 ± 1.09 (−0.31–4.51) |

| Linear wear rate (mm/year) | 0.24 ± 0.13 (−0.05–0.54) |

| Number of followup radiographs used to compute wear rate for each hip | 6 ± 2.8 (3–21) |

| Cup abduction angle (°) | 39.5 ± 7.6 (22–58) |

| Depth of acetabular seating (cm) | 2 ± 2.8 (−8.2–8.1) |

| Time between radiographs and CT (days) | 10 ± 24 (−71–84) |

| Femoral lysis area (cm2) among 45 THAs with femoral osteolysis | 1.71 ± 1.85 (0.14–7.96) |

| Pelvic lysis area (cm2) among 36 THAs with pelvic osteolysis | 3.98 ± 4.04 (0.07–18.47) |

| Total lysis area (cm2) among 48 THAs with pelvic or femoral osteolysis | 4.59 ± 4.21 (0.07–18.72) |

All data are continuous variables and are expressed as mean ± standard deviation, with range in parentheses.

Radiographic reviews were performed by two independent reviewers: one to analyze AP radiographs for femoral and pelvic osteolysis and component stability (CCP) and one to measure wear (SEB). The reviewer who analyzed the radiographs for osteolysis had prior experience interpreting both CT and radiographic images. A third independent reviewer (HE) evaluated the CT scans. Each reviewer was blinded to the results of the other two reviewers.

Acetabular and femoral fixation were assessed on radiographs using established criteria [7, 8, 17]. Osteolytic lesions were also defined as previously described [9] and, when present, were measured using Martell’s Hip Analysis Suite software (University of Chicago Medical Center, Chicago, IL). Depth of seating of the acetabular component to the medial wall was measured by drawing a line perpendicular to the interteardrop line adjacent to the medial edge of the cup and another line adjacent to the lateral side of the radiographic teardrop, measuring the distance between these two lines, and adjusting for the magnification factor based on the diameter of the femoral head.

The wear measurements and the determination of the polyethylene wear rate and volume were carried out on the serial AP radiographs, which had all been taken with the beam centered over the pubic symphysis while the patient was supine with their legs internally rotated. The volumetric wear associated with the 2-D head penetration was determined for each followup radiograph relative to the immediate postoperative view with the Hip Analysis Suite software [12]. Using at least three serial AP pelvic radiographs taken at least 0.75 years postoperatively, a least-squares linear regression was used for each hip to determine the slope of the line that best fit the relationship between the volumetric wear and the time in situ [13, 26]. The slope of the linear regression represented the volumetric wear rate of the polyethylene. Total volumetric wear at the time of the CT scan was calculated by multiplying the volumetric wear rate with the followup interval when the CT scan was obtained. Linear wear rates and total linear head penetration were calculated for each hip in the same fashion using the linear head penetration data derived from Hip Analysis Suite.

Helical CT scans were performed at 140 kV (GE LightSpeed® VCT, General Electric Co, Waukesha, WI; and Siemens Somatom® Sensation 4, Siemens AG, Munich, Germany) and thin axial images (1-3 mm) were reconstructed from raw data. The DICOM-formatted image data were transferred to a personal computer for analysis using a computer-aided imaging program (Muscular-Skeleton Analysis Software, VirtualScopics, Rochester, NY). An automated segmentation algorithm based on a Hounsfield threshold was used to identify the implant. A single observer then traced the boundaries of acetabular osteolytic defects slice by slice. Osteolytic lesions were defined as any demarcated area adjacent to the acetabular component without trabecular bone [16, 21]. The volume of pelvic osteolysis was computed by the software application based on a summation of the user-segmented regions.

To compare the agreement between radiographic and CT findings, sensitivity and specificity were computed for the radiographic interpretation of pelvic osteolysis using the CT findings as a gold standard. Univariate correlations were evaluated to determine the association of pelvic osteolysis volume on CT with each of the patient, implant, and radiographic parameters. A multivariate regression analysis with stepwise variable entry was also performed to determine to what extent any combination of patient, implant, and radiographic factors could be used to estimate the volume of pelvic osteolysis. Patient-related factors considered in our analysis included gender, preoperative diagnosis, age at surgery, height, weight, body mass index, and physician-assessed activity level (Table 1). Implant factors included polyethylene liner geometry and terminal sterilization technique, femoral head material, femoral head diameter, cup outer diameter, and hole plug usage (Table 2). Factors derived from measurement of the radiographs included volumetric wear, volumetric wear rate, linear wear, linear wear rate, cup abduction angle, depth of acetabular seating, femoral osteolytic area, and pelvic osteolytic area (Table 3). Categorical variables were incorporated in the regression analysis using dummy coding (0, 1) [23]. When coding for parameters such as femoral head diameter that included three or more categories, the THAs in each category were compared to all other THAs in the remaining categories (ie, THAs with 32-mm heads were coded as 1 and all other THAs, including those with 22-, 26-, and 28-mm heads, were coded as 0). Interaction terms were created to accommodate the potential influence of shelf storage after gamma irradiation in air.

The magnitude of each factor’s effect was based on the best-fit regression model accounting for the largest portion of the variance in the volumetric pelvic lysis. Because approximately 25 predictor variables were incorporated, an inclusion p value of 0.002 (0.05/25) was used for the regression analysis. The amount of variance of the criterion variable (pelvic osteolysis volume measured on CT) that could be accounted for by the predictor variables was characterized by the coefficient of determination, r2. The equation resulting from the multivariate analysis was then used to calculate a lesion volume for each hip and compared to the volume measured on the CT scan. Limits of agreement using the technique described by Bland and Altman [3] were then calculated to quantify the agreement between CT interpretation of pelvic osteolysis and the estimation of pelvic lysis volume using the optimal regression equation. While the multivariate analysis evaluates how strongly the independent factors are related to the dependent variable (pelvic osteolysis on CT), the limits of agreement assess how accurately the regression equation estimates the pelvis osteolysis volume for individual cases. Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL).

Results

Among the 78 THAs included in this study population, 40 had evidence of pelvic osteolysis on CT. The mean pelvic osteolytic lesion volume among these 40 THAs was 19 ± 20.8 cm3 (standard deviation) (range, 0.2–73.1 cm3). Nine hips had pelvic osteolytic lesion volumes of less 2.5 cm3, 11 had lesions between 2.5 and 10 cm3, 10 had lesions between 10 and 30 cm3, and 10 had lesions greater than 30 cm3. All cups and stems were radiographically stable. Periacetabular osteolysis was identified on plain radiographs in 31 hips of the 40 hips with pelvic osteolysis on CT. Using the CT presence of osteolysis as the gold standard, the interpretation of standard AP pelvis radiographs yielded a sensitivity of 77.5%. Of the nine THAs with osteolysis on CT not identified on radiographs, three hips had defects less than 1 cm3 and the largest lytic defect had a volume of 4.3 cm3. Pelvic osteolysis was read on the radiographs of five THAs without evidence of pelvic osteolysis on CT; thus, the interpretation of standard AP pelvis radiographs yielded a specificity of 86.8%. The areas of the lesions identified on standard radiographs but not identified on CT were all less than 4 cm2; three of these measured less than 1 cm2.

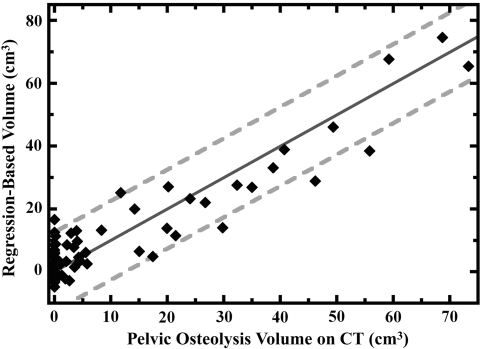

For the multivariate analysis, only the area of pelvic osteolysis measured on radiographs (p = 4 × 10−18), heavy patient activity level (p = 0.00003), and total volume of wear (p = 0.002) were associated with the pelvic osteolysis volume measured on CT (Table 4). The single most important factor was the area of pelvic osteolysis (which accounted for 80% variance in the pelvic osteolysis volume, r = 0.89, r2 = 0.80). When combined with heavy patient activity as assessed by the surgeon and total volume of wear, these three factors accounted for 87% of the variance in the pelvic osteolysis volume (r = 0.93, r2 = 0.87). The volumes calculated by the equation based on the multivariate regression were within 5 cm3 of the actual CT volume for 50 hips (64%), between 5 cm3 and 10 cm3 for 20 hips (26%), and more than 10 cm3 for eight hips (10%) (Fig. 1). The limits of agreement between the calculated volume and the actual volume of pelvic osteolysis measured on CT were ± 12.5 cm3, meaning the volume estimation based on the regression equation was within 12.5 cm3 of the volume measured on CT in 95% of cases.

Table 4.

Association of pelvic osteolytic lesion volume on CT with patient, implant, and radiographic parameters

| Factor | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Correlation coefficient (r) | p value | Incremental r2 | p value | |

| Patient factors | ||||

| Gender (male = 1, female = 0) | 0.28 | 0.01 | 0.60 | |

| Preoperative diagnosis | ||||

| Osteoarthritis | 0.11 | 0.36 | 0.24 | |

| Osteonecrosis | −0.09 | 0.41 | 0.78 | |

| Developmental hip dysplasia | 0.02 | 0.86 | 0.39 | |

| Posttraumatic arthrosis | −0.08 | 0.50 | 0.33 | |

| Inflammatory arthritis | −0.009 | 0.94 | 0.45 | |

| Age at surgery | −0.14 | 0.22 | 0.19 | |

| Height | 0.09 | 0.44 | 0.65 | |

| Weight | −0.10 | 0.40 | 0.65 | |

| Body mass index | −0.17 | 0.14 | 0.74 | |

| Physician-assessed activity level | ||||

| Heavy | 0.54 | 0.0000003 | 0.05 | 0.00003 |

| Moderate | −0.20 | 0.08 | 0.40 | |

| Light | −0.22 | 0.06 | 0.37 | |

| Semisedentary | −0.11 | 0.32 | 0.97 | |

| Implant factors | ||||

| Polyethylene liner geometry | ||||

| 4 mm lateralized | −0.003 | 0.98 | 0.05 | |

| Standard | 0.06 | 0.61 | 0.08 | |

| 10° lip | −0.11 | 0.35 | 0.52 | |

| Terminal sterilization | ||||

| Gas plasma | −0.37 | 0.0008 | 0.18 | |

| Gamma-in-air standard dose | 0.48 | 0.00001 | 0.02 | |

| Gamma-barrier standard dose | −0.07 | 0.56 | 0.29 | |

| Gamma-barrier low dose | −0.06 | 0.62 | 0.74 | |

| Shelf storage duration for gamma-in-air liners | 0.38 | 0.0007 | 0.09 | |

| Femoral head material (ceramic = 1, CoCr = 0) | 0.07 | 0.54 | 0.74 | |

| Femoral head diameter | 0.15 | 0.19 | 0.25 | |

| Cup outer diameter | 0.19 | 0.10 | 0.23 | |

| Hole eliminator | ||||

| Plug with positive stop | −0.25 | 0.03 | 0.84 | |

| Plug without positive stop | 0.17 | 0.14 | 0.90 | |

| Not used | 0.14 | 0.21 | 0.67 | |

| Radiographic factors | ||||

| Years between surgery and CT | 0.50 | 0.000003 | 0.94 | |

| Volumetric wear | 0.51 | 0.000002 | 0.02 | 0.002 |

| Volumetric wear rate | 0.31 | 0.005 | 0.19 | |

| Linear wear | 0.53 | 0.0000006 | 0.84 | |

| Linear wear rate | 0.30 | 0.007 | 0.21 | |

| Number of followup radiographs used to compute wear rate for each hip | 0.42 | 0.0001 | 0.08 | |

| Cup abduction angle | −0.18 | 0.12 | 0.45 | |

| Depth of acetabular seating | 0.11 | 0.34 | 0.33 | |

| Days between radiographs and CT | −0.21 | 0.06 | 0.59 | |

| Femoral lysis area on radiograph | 0.16 | 0.15 | 0.74 | |

| Pelvic lysis area on radiograph | 0.89 | 4 × 10−18 | 0.80 | 4 × 10−18 |

Fig. 1.

Among the 78 THAs included in this study, we found a strong correlation (r = 0.93, r2 = 0.87) between the actual volume of pelvic osteolysis measured on CT and the calculation of lysis volume derived by multiplying the area of the pelvic defect on radiographs measured in cm2 by 3.95 (95% CI, 3.46–4.45), adding the volume of wear measured in cm3 by 4.08 (95% CI, 1.59–6.57), adding 9.56 (95% CI, 5.31–13.81) for patients with heavy activity levels and subtracting 3.49 (95% CI, –6.25 to −0.73) for all hips. However, the calculated values still deviate from exact agreement with the CT volumes (solid dark-gray line), and the limits of agreement are ± 12.5 cm3 (dashed light-gray lines). As a consequence, CT images remain our preferred diagnostic modality when accurate assessments of pelvic osteolysis volume are required.

Discussion

A method to accurately determine the volume of osteolysis is a desirable tool given the potential consequences of large osteolytic lesions. Currently, CT scans are the most sensitive method for diagnosing the presence of osteolysis [5, 14, 21] and the most accurate method for measuring its volume [14, 21]. While large osteolytic lesions can be reliably detected on radiographs, we found that areas of osteolysis measured on the AP radiograph can not accurately estimate the volume of pelvic osteolysis even in concert with other radiographic and patient- and implant-related factors.

One limitation of this study is that biologic and genetic factors that may influence osteolysis were not included in this analysis. More research is needed to identify these factors and quantify their effects. Another major limitation of this study is that although we included a spectrum of defect sizes among our study population, we did not analyze a consecutive series of THAs. We routinely recommend CT scans for all patients, but those with radiographic evidence are more likely to pursue this recommendation. As a consequence, although almost ½ of the hips (38/78) in this study did not demonstrate evidence of osteolysis on CT, the mean defect volume among the 40 THAs with pelvic lysis was 19 cm3. This average defect volume is substantially higher that of several other published studies (Puri et al. [21], 4.9 cm3; Howie et al. [11], 10.3 cm3 and 13.3 cm3; Looney et al. [16], 3 cm3). In addition, results of this analysis are specific to the Duraloc® 100 cup with conventional polyethylene.

When we compared estimates of the 3-D CT volume based on the 2-D radiographic area, patient activity and implant wear with the actual CT volume in this study, we found the limits of agreement ranged from −12.5 to 12.5 cm3, indicating that the estimates were within 12.5 cm3 of the actual volumes for 95% of the cases. Using only the radiographic area of the osteolysis, Kitamura et al. [14] reported limits of agreement of −14.6 cm3 to 18.7 cm3. The improvement in agreement in this study can be attributed to the increased sensitivity (77.5% versus 66.7%) and specificity (86.8% versus 72.4%) of the radiographic review (radiographic findings being the most important factor in estimating osteolysis volume) as well as the inclusion of the volumetric wear and activity level as predictor variables. The increased sensitivity and specificity of the radiographic review in the current study is likely due to the larger average defect size (19 cm3 versus 12.1 cm3).

Like Looney et al. [16] and Howie et al. [11], we also found the total wear volume was associated with the pelvic lysis volume. This finding supports the recommendation that patients demonstrating substantial radiographic evidence of head eccentricity should also be considered candidates for CT scans to rule out the presence of osteolysis, even when the radiographs appear to be negative.

Our analysis also supports the surveillance algorithm proposed by Stulberg et al. [25]. Patients with evidence of pelvic osteolysis on plain radiographs, those with high wear, and those with heavy physician-assessed activity levels are more likely to demonstrate larger osteolytic lesions on CT scans than sedentary patients with little wear and no obvious radiographic evidence of osteolysis. Unfortunately, however, our analysis results could not accurately estimate the volume of an individual osteolysis lesion.

Because we have been unable to accurately determine the volume of pelvic osteolysis without a CT scan, we would recommend a CT scan whenever the volume of osteolysis needs to be precisely known. We consider a CT scan essential for preoperative planning to definitively evaluate the location and extent of the osteolysis and any cortical perforations, the bony support available to the cup, and the amount of bone graft material necessary to fill the defect (if grafting is planned). A CT scan can be used to confirm the extent of the osteolysis when a lesion appears on radiographs and is especially useful if a surgeon has a threshold for intervention based on lesion size, location, or growth rate. Because some large osteolytic lesions can be missed with standard radiographs, a CT scan may also be useful in the evaluation of unexplained pain in an active patient with high wear—for example, we have used CT to diagnose pelvic fractures that were not apparent on radiographs. CT scans are also useful for routine followup intervals (every 5 years, for example) if the patient received a new (or novel) bearing surface or implant. These images would allow the surgeon to characterize the outcome associated with new implants more completely [15]. A large archive of CT images could also enable the collection of more detailed data to guide clinical decision making (such as what types of lesions may predispose a patient to pelvic fracture or cup loosening). Currently, the relationships among lesion volume, location, cortical perforation and pelvic architecture and their effect cup loosening and periprosthetic fracture are unknown. Further research is required in this area.

In summary, a CT scan is recommended whenever the exact size, location, and surface area involvement of a lesion is of interest. We continue to recommend routine CT scans to our patients at 5-year intervals to obtain information that can improve followup and clinical decision making. Routine use of CT allows us to identify small lesions, avoid missing large lesions, and more closely follow the 3-D progression of the osteolysis.

Footnotes

The Anderson Orthopaedic Research Institute has received funding from Inova Health System and from a cooperative agreement awarded and administered by the US Army Medical Research & Materiel Command (USAMRMC) and the Telemedicine & Advanced Technology Research Center (TATRC) to support this study. Two of the authors (CAE and CAE, Jr.) receive royalties from DePuy, a Johnson & Johnson company. One author (CAE, Jr.) serves as a consultant for DePuy and another author (CAE) owns Johnson & Johnson stock.

Each author certifies that his or her institution has approved the human protocol for this investigation and that all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research.

References

- 1.Berry DJ. Periprosthetic fractures associated with osteolysis: a problem on the rise. J Arthroplasty. 2003;18(3 Suppl 1):107–111. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Berry DJ, Lewallen DG, Hanssen AD, Cabanela ME. Pelvic discontinuity in revision total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1999;81:1692–1702. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Bland JM, Altman DG. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet. 1986;1:307–310. [PubMed]

- 4.Chatoo M, Parfitt J, Pearse MF. Periprosthetic acetabular fracture associated with extensive osteolysis. J Arthroplasty. 1998;13:843–845. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Claus AM, Engh CA Jr, Sychterz CJ, Xenos JS, Orishimo KF, Engh CA Sr. Radiographic definition of pelvic osteolysis following total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85:1519–1526. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Dowd JE, Sychterz CJ, Young AM, Engh CA. Characterization of long-term femoral-head-penetration rates: association with and prediction of osteolysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000;82:1102–1107. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Engh CA, Massin P, Suthers KE. Roentgenographic assessment of the biologic fixation of porous-coated femoral components. Clin. Orthop Relat Res. 1990;257:107–128. [PubMed]

- 8.Engh CA Jr, Culpepper WJ 2nd, Engh CA. Long-term results of use of the anatomic medullary locking prosthesis in total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1997;79:177–184. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Engh CA Jr, Sychterz CJ, Young AM, Pollock DC, Toomey SD, Engh CA. Interobserver and intraobserver variability in radiographic assessment of osteolysis. J Arthroplasty. 2002;17:752–759. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Harris WH. The problem is osteolysis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1995;311:46–53. [PubMed]

- 11.Howie DW, Neale SD, Stamenkov R, McGee MA, Taylor DJ, Findlay DM. Progression of acetabular periprosthetic osteolytic lesions measured with computed tomography. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:1818–1825. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Hui AJ, McCalden RW, Martell JM, MacDonald SJ, Bourne RB, Rorabeck CH. Validation of two and three-dimensional radiographic techniques for measuring polyethylene wear after total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85:505–511. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Isaac GH, Dowdson D, Wroblewski BM. An investigation into the origins of time-dependent variation in penetration rates with Charnley acetabular cups—wear, creep or degradation? Proc Inst Mech H. 1996;210:209–216. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Kitamura N, Pappedemos PC, Duffy PR 3rd, Stepniewski AS, Hopper RH Jr, Engh CA Jr, Engh CA. The value of anteroposterior radiographs for evaluating pelvic osteolysis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;453:239–245. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Leung SB, Egawa H, Stepniewski A, Beykirch S, Engh CA Jr, Engh CA Sr. Incidence and volume of pelvic osteolysis at early follow-up with highly cross-linked and noncross-linked polyethylene. J Arthroplasty. 2007;22(6 Suppl 2):134–139. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Looney RJ, Boyd A, Totterman S, Seo GS, Tamez-Pena J, Campbell D, Novotny L, Olcott C, Martell J, Hayes FA, O’Keefe RJ, Schwarz EM. Volumetric computerized tomography as a measurement of periprosthetic acetabular osteolysis and its correlation with wear. Arthritis Res. 2002;4:59–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Massin P, Schmidt L, Engh CA. Evaluation of cementless acetabular migration. An experimental study. J Arthroplasty. 1989; 4:245–251. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Oparaugo PC, Clarke IC, Malchau H, Herberts P. Correlation of wear debris-induced osteolysis and revision with volumetric wear-rates of polyethylene. Acta Orthop Scand. 2001;72:22–28. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Orishimo KF, Claus AM, Sychterz CJ, Engh CA. Relationship between polyethylene wear and osteolysis in hips with a second-generation porous-coated cementless cup after seven years of follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85:1095–1099. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Perez RE, Rodriguez JA, Deshmukh RG, Ranawat CS. Polyethylene wear and periprosthetic osteolysis in metal-backed acetabular components with cylindrical liners. J Arthroplasty. 1998;13:1–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Puri L, Wixson RL, Stern SH, Kohli J, Hendrix RW, Stulberg SD. Use of helical computed tomography for the assessment of acetabular osteolysis after total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84:609–614. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Sánchez-Sotelo J, McGrory BJ, Berry DJ. Acute periprosthetic fracture of the acetabulum associated with osteolytic pelvic lesions: a report of 3 cases. J Arthroplasty. 2000;15:126–130. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Sheskin DJ. Handbook of Parametric and Nonparametric Statistical Procedures: Second Edition. Washington, DC: Chapman & Hall/CRC; 2000.

- 24.Stern SH, CRCPD Committee on Nationwide Evaluation of X-ray Trends, American College of Radiology. Nationwide Evaluation of X-ray Trends (NEXT) Tabulation and Graphical Summary of 2000 Survey of Computed Tomography (CRCPD Publication #E-07-2). Frankfort, KY: Conference of Radiation Control Program Directors, Inc; 2007:1–154.

- 25.Stulberg SD, Wixson RL, Adams AD, Hendrix RW, Bernfield JB. Monitoring pelvic osteolysis following total hip replacement surgery: an algorithm for surveillance. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84(Supp 1):116–122. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Sychterz CJ, Engh CA Jr, Young A, Engh CA. Analysis of temporal wear patterns of porous-coated acetabular components: distinguishing between true wear and so-called bedding-in. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1999;81:821–830. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.United Nations Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation. Sources and effects of ionizing radiation, Vol. 1: Sources. New York, NY: United Nations Publishing; 2000.