Abstract

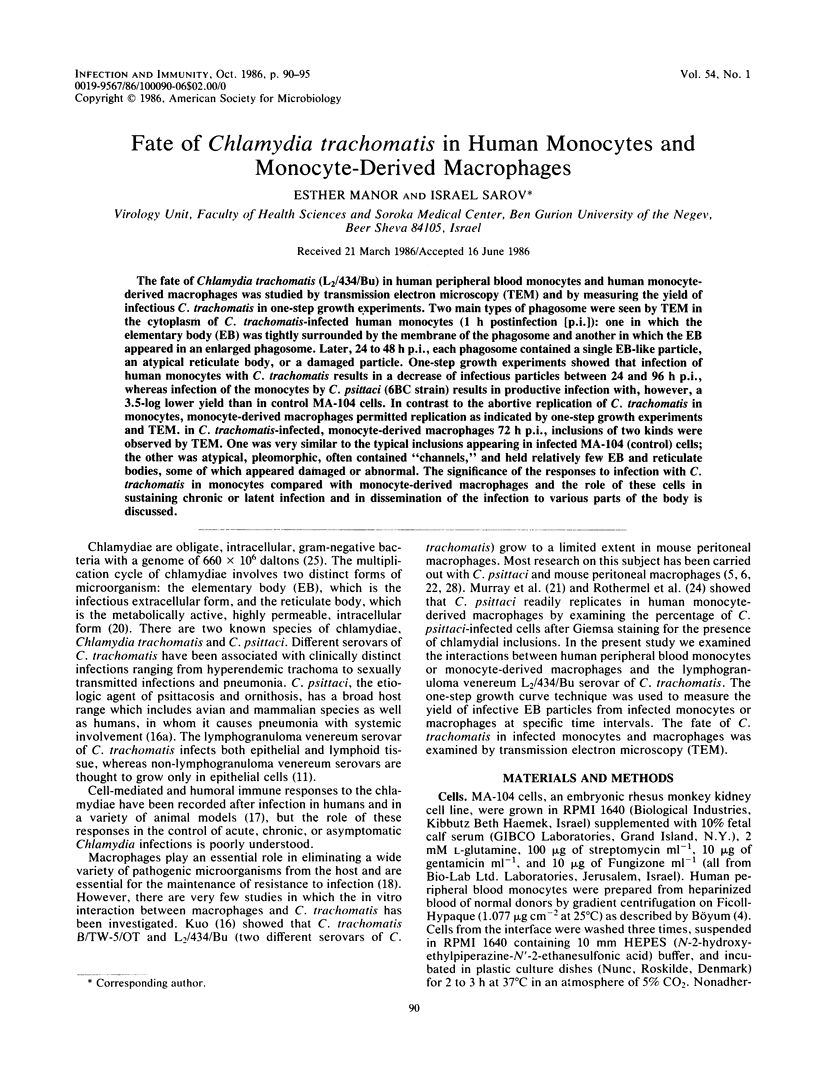

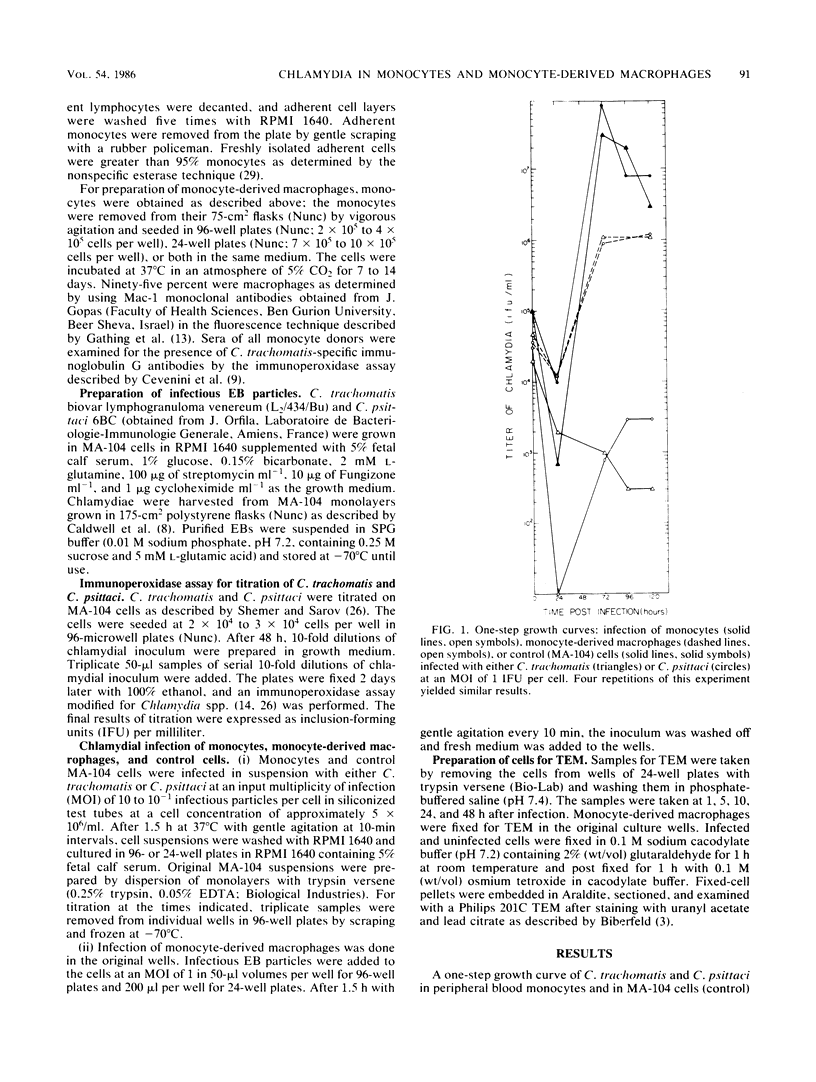

The fate of Chlamydia trachomatis (L2/434/Bu) in human peripheral blood monocytes and human monocyte-derived macrophages was studied by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and by measuring the yield of infectious C. trachomatis in one-step growth experiments. Two main types of phagosome were seen by TEM in the cytoplasm of C. trachomatis-infected human monocytes (1 h postinfection [p.i.]): one in which the elementary body (EB) was tightly surrounded by the membrane of the phagosome and another in which the EB appeared in an enlarged phagosome. Later, 24 to 48 h p.i., each phagosome contained a single EB-like particle, an atypical reticulate body, or a damaged particle. One-step growth experiments showed that infection of human monocytes with C. trachomatis results in a decrease of infectious particles between 24 and 96 h p.i., whereas infection of the monocytes by C. psittaci (6BC strain) results in productive infection with, however, a 3.5-log lower yield than in control MA-104 cells. In contrast to the abortive replication of C. trachomatis in monocytes, monocyte-derived macrophages permitted replication as indicated by one-step growth experiments and TEM. in C. trachomatis-infected, monocyte-derived macrophages 72 h p.i., inclusions of two kinds were observed by TEM. One was very similar to the typical inclusions appearing in infected MA-104 (control) cells; the other was atypical, pleomorphic, often contained "channels," and held relatively few EB and reticulate bodies, some of which appeared damaged or abnormal. The significance of the responses to infection with C. trachomatis in monocytes compared with monocyte-derived macrophages and the role of these cells in sustaining chronic or latent infection and in dissemination of the infection to various parts of the body is discussed.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Arbeit R. D., Zaia J. A., Valerio M. A., Levin M. J. Infection of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells by varicella-zoster virus. Intervirology. 1982;18(1-2):56–65. doi: 10.1159/000149304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behin R., Mauel J., Sordat B. Leishmania tropica: pathogenicity and in vitro macrophage function in strains of inbred mice. Exp Parasitol. 1979 Aug;48(1):81–91. doi: 10.1016/0014-4894(79)90057-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne G. I., Faubion C. L. Inhibition of Chlamydia psittaci in oxidatively active thioglycolate-elicited macrophages: distinction between lymphokine-mediated oxygen-dependent and oxygen-independent macrophage activation. Infect Immun. 1983 May;40(2):464–471. doi: 10.1128/iai.40.2.464-471.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne G. I., Faubion C. L. Lymphokine-mediated microbistatic mechanisms restrict Chlamydia psittaci growth in macrophages. J Immunol. 1982 Jan;128(1):469–474. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne G. I., Moulder J. W. Parasite-specified phagocytosis of Chlamydia psittaci and Chlamydia trachomatis by L and HeLa cells. Infect Immun. 1978 Feb;19(2):598–606. doi: 10.1128/iai.19.2.598-606.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Böyum A. Isolation of mononuclear cells and granulocytes from human blood. Isolation of monuclear cells by one centrifugation, and of granulocytes by combining centrifugation and sedimentation at 1 g. Scand J Clin Lab Invest Suppl. 1968;97:77–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell H. D., Kromhout J., Schachter J. Purification and partial characterization of the major outer membrane protein of Chlamydia trachomatis. Infect Immun. 1981 Mar;31(3):1161–1176. doi: 10.1128/iai.31.3.1161-1176.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cevenini R., Rumpianesi F., Donati M., Sarov I. A rapid immunoperoxidase assay for the detection of specific IgG antibodies to Chlamydia trachomatis. J Clin Pathol. 1983 Mar;36(3):353–356. doi: 10.1136/jcp.36.3.353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniels C. A., Kleinerman E. S., Snyderman R. Abortive and productive infections of human mononuclear phagocytes by type I herpes simplex virus. Am J Pathol. 1978 Apr;91(1):119–136. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Einstein L. P., Schneeberger E. E., Colten H. R. Synthesis of the second component of complement by long-term primary cultures of human monocytes. J Exp Med. 1976 Jan 1;143(1):114–126. doi: 10.1084/jem.143.1.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gathings W. E., Lawton A. R., Cooper M. D. Immunofluorescent studies of the development of pre-B cells, B lymphocytes and immunoglobulin isotype diversity in humans. Eur J Immunol. 1977 Nov;7(11):804–810. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830071112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haikin H., Sarov I. Determination of specific IGA antibodies to varicella zoster virus by immunoperoxidase assay. J Clin Pathol. 1982 Jun;35(6):645–649. doi: 10.1136/jcp.35.6.645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handman E., Ceredig R., Mitchell G. F. Murine cutaneous leishmaniasis: disease patterns in intact and nude mice of various genotypes and examination of some differences between normal and infected macrophages. Aust J Exp Biol Med Sci. 1979 Feb;57(1):9–29. doi: 10.1038/icb.1979.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunimoto D., Brunham R. C. Human immune response and Chlamydia trachomatis infection. Rev Infect Dis. 1985 Sep-Oct;7(5):665–673. doi: 10.1093/clinids/7.5.665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo C. C. Cultures of Chlamydia trachomatis in mouse peritoneal macrophages: factors affecting organism growth. Infect Immun. 1978 May;20(2):439–445. doi: 10.1128/iai.20.2.439-445.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladany S., Sarov I. Recent advances in Chlamydia trachomatis. Eur J Epidemiol. 1985 Dec;1(4):235–256. doi: 10.1007/BF00237099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MACKANESS G. B. Cellular resistance to infection. J Exp Med. 1962 Sep 1;116:381–406. doi: 10.1084/jem.116.3.381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mogensen S. C. Role of macrophages in natural resistance to virus infections. Microbiol Rev. 1979 Mar;43(1):1–26. doi: 10.1128/mr.43.1.1-26.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray H. W., Byrne G. I., Rothermel C. D., Cartelli D. M. Lymphokine enhances oxygen-independent activity against intracellular pathogens. J Exp Med. 1983 Jul 1;158(1):234–239. doi: 10.1084/jem.158.1.234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orfila J., Haider F., Bissac E. Etude de la sensibilité des macrophages de souris de race pure á Chlamydia psittaci. Bull Eur Physiopathol Respir. 1983 Mar-Apr;19(2):147–149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papaevangelou G., Roumeliotou-Karayannis A., Contoyannis P. Changing epidemiological characteristics of acute viral hepatitis in Greece. Infection. 1982 Jan;10(1):1–4. doi: 10.1007/BF01640826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rikihisa Y., Ito S. Localization of electron-dense tracers during entry of Rickettsia tsutsugamushi into polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Infect Immun. 1980 Oct;30(1):231–243. doi: 10.1128/iai.30.1.231-243.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothermel C. D., Rubin B. Y., Murray H. W. Gamma-interferon is the factor in lymphokine that activates human macrophages to inhibit intracellular Chlamydia psittaci replication. J Immunol. 1983 Nov;131(5):2542–2544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarov I., Becker Y. Trachoma agent DNA. J Mol Biol. 1969 Jun 28;42(3):581–589. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(69)90245-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shemer Y., Sarov I. Inhibition of growth of Chlamydia trachomatis by human gamma interferon. Infect Immun. 1985 May;48(2):592–596. doi: 10.1128/iai.48.2.592-596.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva S. R., Meirelles S. S., De Souza W. Mechanism of entry of Toxoplasma gondii into vertebrate cells. J Submicrosc Cytol. 1982 Jul;14(3):471–482. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyrick P. B., Brownridge E. A., Ivins B. E. Interaction of Chlamydia psittaci with mouse peritoneal macrophages. Infect Immun. 1978 Mar;19(3):1061–1067. doi: 10.1128/iai.19.3.1061-1067.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yam L. T., Li C. Y., Crosby W. H. Cytochemical identification of monocytes and granulocytes. Am J Clin Pathol. 1971 Mar;55(3):283–290. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/55.3.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeichner S. L. Isolation and characterization of macrophage phagosomes containing infectious and heat-inactivated Chlamydia psittaci: two phagosomes with different intracellular behaviors. Infect Immun. 1983 Jun;40(3):956–966. doi: 10.1128/iai.40.3.956-966.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]