Abstract

Objective

The objective of this study was to determine the capacity of chondrocyte-and mesenchymal stem cell (MSC)-laden hydrogel constructs to achieve native tissue tensile properties when cultured in a chemically defined medium supplemented with transforming growth factor-beta3 (TGF-β3).

Design

Cell-laden agarose hydrogel constructs (seeded with bovine chondrocytes or MSCs) were formed as prismatic strips and cultured in a chemically defined serum-free medium in the presence or absence of TGF-β3. The effects of seeding density (10 versus 30 million cells/mL) and cell type (chondrocyte versus MSC) were evaluated over a 56 day period. Biochemical content, collagenous matrix deposition and localization, and tensile properties (ramp modulus, ultimate strain, and toughness) were assessed bi-weekly.

Results

Results show that the tensile properties of cell seeded agarose constructs increase with time in culture. However, tensile properties (modulus, ultimate strain, and toughness) achieved on day 56 were not dependent on either the initial seeding density or the cell type employed. When cultured in medium supplemented with TGF-β3, tensile modulus increased and plateaued at a level of 300–400 kPa for each cell type and starting cell concentration. Ultimate strain and toughness also increased relative to starting values. Collagen deposition increased in constructs seeded with both cell types and at both seeding densities, with exposure to TGF-β3 resulting in a clear shift towards type II collagen deposition as determined by immunohistochemical staining.

Conclusions

These findings demonstrate that the tensile properties, an important and often overlooked metric of cartilage development, increase with time in culture in engineered hydrogel-based cartilage constructs. Under the free-swelling conditions employed in the present study, tensile moduli and toughness did not match that of the native tissue, though significant time-dependent increases were observed with the inclusion of TGF-β3. Of note, MSC-seeded constructs achieved tensile properties that were comparable to chondrocyte-seeded constructs, confirming the utility of this alternative cell source in cartilage tissue engineering. Further work, including both modulation of the chemical and mechanical culture environment, is required to optimize the deposition of collagen and its remodeling to achieve tensile properties in engineered constructs matching the native tissue.

Keywords: Cartilage, Tissue Engineering, Tensile Testing, Chondrocytes, 3D Culture, Mesenchymal Stem Cells

Introduction

As the load bearing material of diarthrodial joints, articular cartilage functions in a challenging mechanical environment. This requires that the tissue properties be uniquely adapted to its load-bearing role, including low-friction interactions with opposing surfaces and marked durability and self-renewal over a lifetime of use 1. To enable such function, the dense cartilage extracellular matrix (ECM), comprised of type II collagen and sulfated proteoglycan (GAG), is continually remodeled by the resident chondrocytes in response to the loading environment 2. These constituents provide for the tissue tensile and compressive properties that resist excess deformation 3. With trauma or disease, significant deleterious changes may occur, resulting in the emergence of osteoarthritic lesions on the bearing surfaces 4.

Poor endogenous cartilage healing capacity has motivated numerous tissue engineering (TE) approaches to generate functional equivalents 5. In these endeavors, a now standard approach has emerged in which chondrocytes are combined with fibrous networks 6, 7, 8 or hydrogels 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14. More recently, due to limitations in autologous chondrocyte supply, marrow derived mesenchymal stem cells (MSC) have been explored as an alternative cell source. These cells differentiate towards a chondrocyte-like phenotype in defined media in the presence of transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) family members when cultured as pellets, or in hydrogels, porous foams, and fibrous assemblies 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21.

Regardless of cell source, cartilage constructs are routinely evaluated after in vitro or in vivo culture for ECM content, gene expression, and histological appearance. When used as an outcome parameter, mechanical properties of constructs have primarily been assessed in compression (confined and unconfined). These studies have shown that compressive properties improve with increasing culture duration and cell seeding density 11, 22, 23 as well as with the inclusion of anabolic growth factors and/or increased serum supplementation 24, 25, 26. With long-term culture using specialized media and/or bioreactor culture, equilibrium properties have matched that of the native tissue 27, 28. For example, we have recently shown that a defined serum free media supplemented with TGF-β3 markedly improved the compressive properties of chondrocyte-seeded agarose compared to those maintained in the absence of TGF-β3 or in serum containing medium 17. However, in that same study, MSCs produced inferior properties compared to age and donor-matched chondrocytes.

In addition to these oft measured compressive properties, the tensile properties of cartilage play a significant role in its mechanical function. It has long been noted that cartilage tensile properties are higher than compressive properties 29. Kempson reported that the ramp tensile modulus of human superficial zone femoral head cartilage ranges from 75–150 MPa 30. For superficial bovine samples, equilibrium tensile moduli increase with age and range from 6–15 MPa (with failure strains of ~60%), while compressive properties at equilibrium are much lower (<1MPa) 31, 32. The large disparity in tensile and compressive properties is termed tension compression non-linearity (TCNL) 33, 34. Under certain compressive loading configurations (e.g., unconfined compression), failure to include TCNL results in poor theoretical predictions of transient response 35. Therefore, many of the poroelastic and biphasic cartilage models have been altered to incorporate TCNL 35, 36. Further highlighting the importance of these properties, cartilage tensile properties decrease rapidly after insult and are a precursor to further degeneration 37.

While critical for cartilage function, few studies have directly examined the tensile properties of engineered cartilage. Rather, most studies indirectly assess this parameter by measuring the dynamic modulus in unconfined compression (a measure dependent on both the compressive and tensile modulus). It has been noted that even when the equilibrium compressive modulus (and GAG content) matches that of the native tissue, the dynamic modulus (and collagen content) remains lower (~25% of native) 38. While less common, several studies have directly measured the tensile properties of engineered constructs (Table 1). Collectively, these studies indicate that the tensile properties of chondrocyte monolayers, masses, and cell-seeded hydrogels remain well below native tissue levels, even after extensive periods of in vitro or in vivo culture. While illustrative, these studies did not employ a defined media with growth factor supplementation, nor did they assess the potential of MSCs to recapitulate this important property in 3D culture.

Table 1.

Tensile Properties of Tissue Engineered Cartilage

| SOURCE |

TE CONSTRUCT |

CULTURE CONDITIONS |

TENSILE PROPERTY |

VALUE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fedewa et al, 199853 | Chondrocyte Monolayer |

In vitro Free-swelling (4–8 weeks) |

Ramp Modulus | 1–5 MPa |

| Gemmiti et al, 200654 | Chondrocyte Monolayer | Static Control (17 days) Fluid Flow (17 days) |

Ramp Modulus Ultimate Strength Ramp Modulus Ultimate Strength |

1.5 MPa 0.6 MPa 2.3 MPa 0.8 MPa |

| Aufderheide and Athanasiou, 200755 | Self-Assembled Chondrocyte Mass |

In vitro Free-swelling (4 weeks) |

Ramp Modulus Ultimate Strength |

0.23 MPa 0.009 MPa |

| Williams et al, 200542 | Chondrocyte-Seeded Alginate |

In vitro Free-swelling (2 weeks) |

Equilibrium Modulus | 0.01 MPa |

| Gratz et al, 20065,6 | Chondrocyte-Seeded Fibrin |

In vivo Repair (8 months) |

Equilibrium Modulus Failure Strain |

0.64 MPa 66% |

Therefore, the purpose of this study was to assess the tensile properties of hydrogel-based constructs seeded with chondrocytes and MSCs and maintained in a defined media. Based on our previous findings of robust increases in compressive properties in this media with TGF-β3, we hypothesized that this treatment would similarly increase construct tensile properties. Further, based on previous studies focusing on compressive properties, we hypothesized that increasing chondrocyte seeding density would produce constructs with greater tensile properties. Finally, we hypothesized that MSC-laden constructs would increase in tensile properties only when exposed to TGF-β3, but would do so to a lesser extent than chondrocyte-laden constructs.

To test these hypotheses, chondrocyte-seeded constructs were formed at two seeding densities (10 and 30 million cells/mL) and cultured for 8 weeks in a defined medium, with or without TGF-β3. Additionally, donor-matched MSCs were seeded (10 million cells/mL) and cultured similarly. At biweekly intervals, the ramp modulus, ultimate strain and toughness were determined using tensile tests to failure. Biochemical content (DNA, GAG, and collagen) was analyzed and ECM distribution and collagen type determined via histology and immunohistochemistry. Findings show that the tensile properties of cell-seeded constructs increased with increasing culture duration and the application of TGF-β3. Interestingly, increasing chondrocyte density increased the initial rate of accumulation of ECM and tensile modulus, but did not alter the modulus values achieved after 8 weeks. Further, when cultured at the same seeding density, chondrocytes and MSCs generated similar increases in tensile properties. Neither cell type nor higher seeding density resulted in constructs whose tensile properties matched that of native cartilage, highlighting the need for further refinement of these engineered constructs to enable their load bearing role once implanted in vivo.

Materials and Methods

MSC AND CHONDROCYTE ISOLATION

Bone marrow derived MSCs were harvested from the carpal bones of 3–6 month old calves (Fresh Farms Beef, Rutland, VT and Research 87, Boylston, MA). Typically, six separate marrow isolations (minimum of three animals) were carried out. Trabecular regions were removed with a saw and agitated in a solution of high glucose Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (hgDMEM) supplemented with 2% penicillin/streptomycin/Fungizone (PSF) and 300 U/mL of heparin. The resulting solution was centrifuged (5 min at 300×g) and plated into 10 cm tissue culture plates. Cultures were maintained in hgDMEM supplemented with 1% PSF and 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) changed twice weekly until confluence. Sub-culturing was carried out at a 1:1 ratio up to passage two. Cartilage pieces was harvested from the carpometacarpal joints of the same group of animals, rinsed in hgDMEM containing 2% PSF and 10% FBS, and incubated at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator for five days (one medium change) to ensure sterility. Pieces were then combined and digested sequentially with pronase and collagenase 10. Chondrocyte suspensions were filtered (70µm cell strainer, BD Falcon, Bedford, MA), pelleted (5 min, 300×g), resuspended in hgDMEM, and viable cells counted. Chondrocytes were encapsulated immediately upon isolation.

CONSTRUCT FABRICATION AND 3D CULTURE

For all studies, type VII agarose (Sigma, St Louis, MO) in PBS was cast in 2.25mm thick sheets, gelled for 20 minutes at 25°C, and cut into strips (7mm × 40mm). For validation studies, acellular strips of 2, 3, 4 and 5% w/v were prepared. For seeding studies, sterile agarose (49°C, 4% w/v) was combined 1:1 with chondrocytes (20 or 60 million cells/mL) or MSCs (20 million cells/mL) at 25°C in chemically defined medium (CM). CM consisted of hgDMEM supplemented with 1X PSF, 0.1 mM dexamethasone, 50mg/mL ascorbate 2-phosphate, 40mg/mL L-proline, 100mg/mL sodium pyruvate, 1X ITS+(6.25µg/ml insulin, 6.25µg/ml transferrin, 6.25ng/ml selenous acid, 1.25mg/ml BSA, and 5.35µg/ml linoleic acid). Constructs were cultured for 56 days in 6 mL/strip with (CM+) or without (CM−) 10ng/mL TGF-β3 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). Strips from two replicate experiments with different cell isolations were used and media was changed twice weekly. At biweekly intervals, constructs were evaluated for tensile properties, biochemical content, and ECM distribution.

CONSTRUCT MECHANICAL TESTING

To evaluate tensile properties, an Instron 5848 Microtester (Instron, Canton, MA) was used to apply uniaxial tension to strips seated into 120 grit sandpaper-coated grips at 25°C. Sample dimensions were measured via digital caliper, and gauge length noted after placement in grips. Samples were moistened with PBS during the test. Elongation was prescribed at a quasi-static 0.5%/sec strain rate until failure. Texture correlation analysis was used to ensure that slippage did not occur at grips by incorporating carbon shavings and computing local deformation from images using Vic2D (Correlated Solutions, Inc. Columbia, SC). Computed local strains showed good agreement with the nominal grip-to-grip strain, and failure occurred catastrophically without slipping (not shown). The ramp tensile modulus was calculated from the measured geometry on the day of testing and the linear region of the stress-strain curve. Ultimate strain (strain at maximum stress) and toughness (integrated area under the stress-strain curve) was calculated for each sample.

BIOCHEMICAL ANALYSIS

For biochemical analysis, disks (Ø4mm) were punched from one end of each strip prior to testing. Samples were weighed wet and digested for 16 hours in papain (0.56U/ml in 0.1M sodium acetate, 10M cysteine HCL, 0.05M EDTA, pH 6.0) at 60°C. Digest was analyzed for GAG content using the DMMB dye-binding assay 39, with chondroitin-6-sulphate as a standard. Collagen content was determined after acid hydrolysis using the orthohydroxyproline (OHP) assay 40, with a 1:10 OHP:collagen ratio 6. DNA content was determined using the PicoGreen dsDNA assay (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) 17.

HISTOLOGY

Samples were fixed overnight at 4°C in paraformaldehyde, dehydrated in a graded series of ethanol, and embedded in paraffin (Paraplast, Lab Storage Systems, St. Peters, MO). Sections were prepared at 8µm and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) for general histology, Alcian Blue (pH 1.0) for GAG or Picrosirius Red for collagens.

IMMUNOHISTOCHEMISTRY

For immunohistochemistry, sections were deparaffinized, rehydrated, and incubated for 1 hour at 37°C in 300µg/mL hyaluronidase (Type IV, Sigma) in PBS. Samples were washed, treated with 3% H202, and incubated with a blocking reagent (DAB150 IHC Select, Millipore, Billerica, MA). Collagens were identified with 5µg/ml dilutions of primary antibodies specific for either collagen I (MAB3391, Millipore) or collagen II (11-116B3, Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, Iowa City, IA) in 3% BSA in PBS. Non-immune controls were prepared with 3% BSA in PBS without primary antibody. Biotinylated goat anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibodies with Streptavidin HRP bound the primary antibody and were reacted with DAB chromagen reagent for 10 minutes (DAB150 IHC Select, Millipore). Color images were captured at 5X magnification using a microscope equipped with a color CCD digital camera and the QCapturePro acquisition software. For each antibody, all samples were stained at the same time and imaged under the same conditions to enable comparison between groups.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

All statistical analysis was performed with SYSTAT software (v10.2, SYSTAT Software Inc., San Jose, CA). Significance was set at p<0.05 and data analyzed using two separate ANOVA analyses. Time, culture medium (CM− or CM+) and either seeding density (10 or 30 million cell/mL) or cell type (Chondrocyte or MSC) were the independent variables. When the ANOVA analysis indicated significance, Fisher’s LSD posthoc tests were applied to enable comparisons between groups. All data are reported as mean ± SD of 7–10 samples.

RESULTS

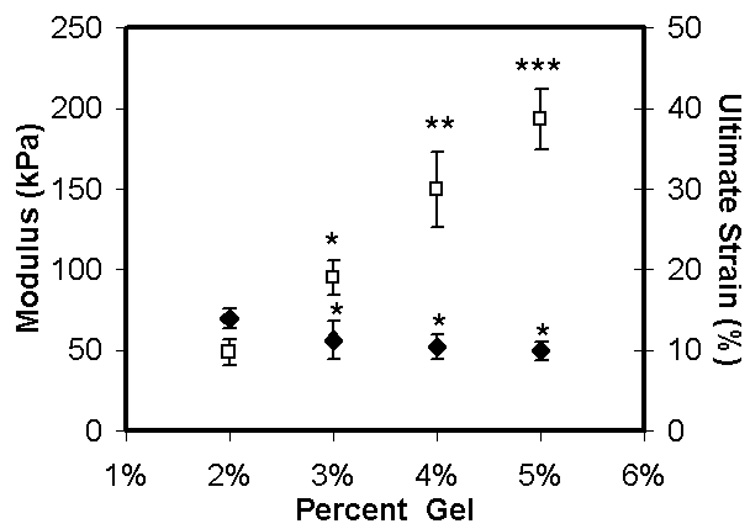

TENSILE PROPERTIES OF ACELLULAR AGAROSE

Preliminary tensile testing of acellular agarose was performed for a range of concentrations (2–5%) to establish testing parameters and to verify gripping conditions. The ramp tensile modulus increased for each percentage increase in agarose concentration (Figure 1, p<0.05). Ultimate strain in these acellular gels was relatively insensitive to increasing concentration, with failure occurring at <15%. A small decrease in ultimate strain was observed at agarose concentrations greater than 2% (Figure 1, p<0.05).

Figure 1. Tensile properties of acellular agarose hydrogels.

Tensile ramp modulus (white squares) and ultimate strain (black diamonds) of acellular gels as a function of agarose content (% w/v). Data represents the mean and standard deviation of ten samples per group. * Indicates difference from 2% group, p<0.05; ** indicates greater than 3% group, p<0.05; *** indicates greater than 4% group, p<0.05.

BIOCHEMICAL CONTENT OF CELL-SEEDED AGAROSE

Effect of Cell Density

After test validation, chondrocyte-laden constructs, seeded at 10 and 30 million cells/mL (CH10M and CH30M, respectively), were fabricated and maintained in long-term culture in either CM− or CM+. DNA content increased with time in CH10M groups in CM+ (p<0.01 vs. day 14, Figure 2), but showed no increase until day 56 compared to day 14 in CM− (p=0.015 vs. day 14). In contrast, DNA content remained stable for CH30M groups in CM+ (p>0.06 vs. day 14). DNA content was higher at all time points except day 56 for CH30M compared to CH10M in CM+ (p<0.05). Both GAG and collagen content were dependent on culture duration and media composition (p<0.001, Figure 2). After day 14 for the CH10M group, and after day 28 for the CH30M group, increased GAG and collagen were found in constructs in CM+ compared to CM−. With seeding at the higher density and culture in CM+, CH30M constructs contained greater GAG and collagen compared to CH10M constructs at all time points after day 14 (p<0.04). Interestingly, CH30M strips maintained in CM− synthesized comparable GAG and collagen by day 56 compared to CH10M groups in CM+ (p=0.129 for GAG, p=0.905 for collagen).

Figure 2. Biochemical composition of tensile strips with variation in time in culture, media condition, cell type, and cell density.

Top row: DNA content (µg/disk); middle row: sGAG content (%ww); bottom row: collagen content (%ww). * Indicates greater than all values lower in both CM− and CM+ conditions within cell and seeding density group (p<0.05); ** indicates greater than all values lower in both CM− and CM+ conditions within cell and seeding density group (p<0.05); # indicates greater than corresponding CH10M value at same time point and media condition (p<0.05); & indicates lower than corresponding CH10M value at same time point and media condition (p<0.05). Data represent the mean and standard deviation of seven to ten samples per group per time point.

Effect of Cell Type

To evaluate the ability of MSCs to produce functional matrix, donor-matched MSCs were seeded at 10 million cells/mL (MSC10M) and compared to the CH10M group. DNA content of MSC10M groups did not change with time, regardless of media condition (p>0.08, Figure 2). MSC10M in CM+ produced similar GAG compared to CH10M CM+ at all time points (p>0.25). Although collagen content was similar between MSC10M and CH10M at the terminal time point (p>0.1), collagen increased more rapidly in MSC10M groups. MSC10M constructs maintained in CM− failed to deposit appreciable amounts of GAG or collagen regardless of time in culture.

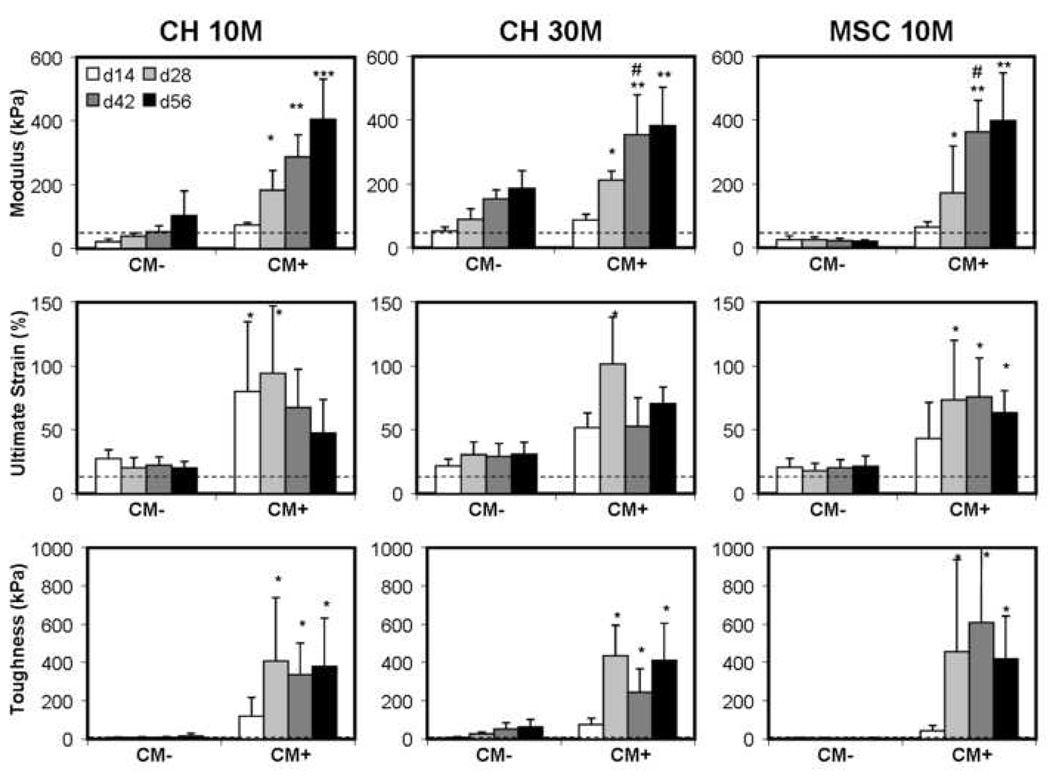

TENSILE PROPERTIES OF CELL-SEEDED AGAROSE

Effect of Cell Density

The tensile modulus of CH10M constructs increased with time in culture in CM+, reaching 405±127 kPa by day 56 (p<0.001 vs. day 14, Figure 3). In contrast, constructs in CM− were significantly weaker in tension, only reaching 104±76 kPa at the terminal time point (p<0.001). When maintained in CM+, CH30M constructs increased in tensile properties with time (p<0.001), and did so more rapidly than CH10M constructs (e.g., note higher modulus in CH30M on day 42). However, the tensile modulus achieved in the CH30M group plateaued by day 42 at a value of 354±125 kPa. When maintained in CM−, CH30M constructs improved in tensile modulus with time (p<0.001 at day 56 vs. day 14) and at day 56, attained similar tensile properties as day 28 CH10M constructs in CM+ (p>0.9). Interestingly, although biochemical content was higher in CH30M constructs in CM+ compared to CH10M, the tensile modulus was not different on day 56. The ultimate strain and toughness of chondrocyte-laden constructs were dependent on time in culture (p<0.01) and media condition (p<0.001), but not on seeding density (p>0.8). Unlike the tensile modulus, which rose steadily through the culture duration, the ultimate strain and toughness of the CH10M and CH30M groups in CM+ reached their highest values by day 28 and were not different from one another thereafter (p>0.1). The ultimate strain achieved was higher for constructs in CM+ compared to CM− at all time points, regardless of seeding density (p<0.05). In contrast, the toughness of constructs in CM+ was not different than CM− constructs until day 28 (p>0.07 day 14 CM+ vs. CM−).

Figure 3. Time-dependent tensile modulus (kPa), ultimate strain (%), and toughness (kPa) of constructs with culture in CM− or CM+ medium.

* Indicates greater than all values lower in both CM− and CM+ conditions within cell and seeding density group (p<0.05); ** indicates greater than all values lower in both CM− and CM+ conditions within cell and seeding density group (p<0.05); *** indicates greater than all lower values within same cell type and seeding density group (p<0.05); # indicates greater than corresponding CH10M value at same time point and media condition (p<0.05). Data represent the mean and standard deviation of seven to ten samples per group per time point. Dotted line indicates corresponding property of 2% agarose from acelluluar studies.

Effect of Cell Type

As expected based on the weak deposition of matrix, MSC10M constructs in CM− did not show any improvement in tensile properties with time (p>0.8 at day 56 vs. day 14). In CM+, however, MSC10M constructs increased in tensile modulus with time (p<0.001), and did so more rapidly than CH10M constructs. Tensile moduli in these constructs plateaued at day 42 to values of 363±99 kPa. The ultimate strain and toughness of MSC10M constructs were dependent on time in culture (p<0.01) and media condition (p<0.001), but were not different than the CH10M group similarly maintained (p>0.25).

HISTOLOGICAL ANALYSIS

Histological analysis showed an increasing amount of matrix deposition with culture duration, with more intense staining with culture in CM+ (not shown). Very little matrix was deposited in the MSC10M group maintained in CM−. As expected from analysis of biochemical content, day 56 constructs cultured in CM+ showed little difference in staining intensity with variations in seeding density and cell type with respect to cellularity, and GAG and collagen deposition (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Histologic appearance of constructs on day 56.

H&E, Alcian Blue and Picrosirius Red staining of CH10M, CH30M and MSC10M constructs cultured in CM+ reveals no differences between groups at day 56. Constructs cultured in CM− conditions (not shown) showed lower staining intensities for chondrocyte groups, and absence of stain for MSCs. Scale bar: 200µm.

The type of collagen deposition in the different culture conditions was analyzed using immunohistochemistry (Figure 5). Interestingly, chondrocytes at either density deposited a mixture of type I and type II collagen in CM−. Addition of TGF-β3 resulted in a dramatic shift in matrix deposition in these constructs, with nearly all collagen deposited being type II. Conversely, MSC-laden constructs showed weak pericellular staining of type I collagen and no type II collagen in CM−, indicative of their lack of chondrogenic phenotype in this media. However, when cultured in CM+, a robust deposition of type II collagen was observed, and pericellular type I collagen staining was lost.

Figure 5. Immunohistochemical detection of amount and distribution of collagen type I and type II in day 56 constructs cultured in CM− or CM+ medium.

Chondrocyte-laden constructs stained for both type I and type II collagen in CM− conditions, with an intense shift to predominantly type II collagen and loss of type I staining in CM+ conditions, regardless of seeding density. MSCs showed some pericellular staining of type I collagen and no type II collagen in CM− conditions, but a robust deposition of type II collagen throughout the construct with culture in CM+ conditions. Scale bar: 200µm.

Discussion

The load bearing capacity of articular cartilage is enabled by a high compressive modulus and an even higher tensile modulus. While compressive properties have been widely studied as a benchmark of mechanical functionality in engineered cartilage, few studies using hydrogels have examined tensile properties or have sought to optimize this critical determinant of cartilage mechanical function. In this study, we directly measured the tensile properties of cell-laden agarose, a commonly used hydrogel in cartilage TE. In agreement with previous studies 41, agarose tensile properties were dependent on the percent composition, and acellular gels failed at strains of >15%, independent of percent composition. When seeded with chondrocytes or MSCs, these properties increase with culture duration, with the largest improvement in tensile properties observed in a chemically defined medium containing TGF-β3. Such seeded constructs increased in ultimate strain to >50% (matching native values); however, the tensile moduli achieved after 8 weeks were a fraction (10% or lower) of native values, which range from 5–50MPa 34.

In addition to assessing baseline tensile properties, this study explored several parameters for improving construct maturation. First, we used a chemically defined medium with (CM+) or without (CM−) TGF-β3 supplementation. We have previously shown that chondrocytes cultured in agarose cylinders in this medium increase in compressive properties with time in culture, with markedly larger improvements with the inclusion of TGF-β3 17. In this study, CM+ medium similarly resulted in larger increases in the biochemical composition (GAG and collagen content) as well as the tensile properties of chondrocyte-laden constructs compared to those maintained in CM−. Additionally, while both type I and type II collagen were deposited by chondrocytes in CM−, a pronounced shift to the accumulation of type II collagen was observed in CM+.

Additional experiments demonstrated that increasing the initial chondrocyte seeding density modulated the rate and amount of construct ECM deposition. In general, an increased starting cellularity led to more rapid and/or higher final biochemical content. For example, constructs seeded with chondrocytes at 30 million cells/mL in CM− reached higher tensile moduli and greater biochemical content on day 56 than 10 million cells/mL constructs similarly maintained. These findings are consistent with previous short-term (14 day) studies that directly measured tensile properties of chondrocyte-laden alginate gels at varying seeding densities 42. This increase in biochemical content with increased seeding density was apparent in CM+ as well. However, despite higher GAG and collagen content at the terminal time point (day 56) in the higher seeding density constructs, the tensile properties achieved were comparable between the two groups. This suggest that factors other than GAG and bulk collagen content, such as collagen cross-linking or expression and deposition of other cross-linking elements, may play a role in increasing tensile properties. Furthermore, given the relatively low collagen levels (0.8–1.1%) observed in these constructs, our findings suggest that there exists a threshold below which composition does not correlate with tensile properties as it does for the native tissue.

Finally, a separate set of experiments explored the capacity of MSCs to develop tensile properties comparable to chondrocytes. In a previous study, we showed that MSCs were unable to achieve comparable compressive properties compared to chondrocytes. One interesting observation in that study was that collagen contents were similar between MSC and chondrocyte-laden cylinders. In this study, MSC-laden constructs attained similar collagen content and tensile properties on day 56 compared to donor-matched chondrocytes at the same density. Staining for collagen type showed that MSCs and chondrocytes responded differently to the varying media conditions. While chondrocytes deposited matrix containing both type I and II collagens in the absence of TGF-β3, MSCs showed only slight accumulation of type I collagen. This finding indicated that MSCs were viable in CM−, but deposited very little ECM. Addition of TGF-β3 shifted the phenotype of both cell types towards one that was strongly chondrogenic, with the majority of collagen deposited being type II. These quantitative and qualitative measures demonstrate, for the first time, that MSCs can form cartilaginous constructs with tensile properties similar to those formed by chondrocytes in a 3D hydrogel environment. This potential is critical for the optimization of this cell source as a viable alternative to chondrocytes for cartilage TE.

From these studies, it is clear that the culture of either chondrocytes or MSCs in agarose results in lower tensile properties and collagen content (~1% of wet weight) than that of the native tissue. This finding is consistent with previous studies that have matched the GAG content and compressive properties of the native tissue in engineered constructs, but have failed to achieve physiologic collagen content, resulting in significantly lower dynamic moduli in unconfined compression 27,38. Additionally, collagen organization (assessed via polarized light microscopy) was isotropic and disorganized in these constructs compared to the ordered collagen alignment in the cartilage superficial layer (not shown). Given that tensile properties are based on a dense, ordered collagen component and are critical to cartilage function, these limitations must be resolved to enable successful engineering of this unique tissue.

Several enabling technologies may be considered for the improvement of these tensile properties. First, it may be that the non-biodegradable agarose used in this study interferes with the distribution and remodeling of the forming collagen network. Previous studies using pulse-chase radiolabeling have shown that spatial and temporal gradients in newly formed matrix constituents control the distance from the cell that products migrate 43. Hydrogels that are engineered to degrade on a specific time scale 44 or via hydrolysis of enzymatically cleavable elements 45 might improve ECM distribution, and may likewise promote increases in tensile properties. Alternatively, fabrication of hydrogels from biologics, such as hyaluronic acid (HA) or chondroitin sulfate (CS), may permit natural ECM remodeling with construct maturation 9, 46, 47.

In addition to hydrogel modifications, the mechanical growth environment may be altered to enhance tensile properties. After birth, articular cartilage remodels considerably, with collagen fiber organization transforming from an isotropic arrangement to a mature configuration with superficial fibers parallel to the surface 48. This remodeling increases cartilage properties (particularly the tensile properties) 30, 49, 50. In bovine cartilage, these increases in tensile properties correlate with increases in collagen content and cross-linking 31, 32, 51. Most interestingly, when embryonic and juvenile bovine cartilage explants are removed from the loading environment, the tensile properties decrease in conjunction with decreases in collagen and cross-link density 52. These findings suggest that the demands placed on cartilage, coincident with load-bearing use, lead to rapid changes in collagen content and organization, allowing the tissue to achieve its mature load bearing capacity. Incorporation of mechanical stimulation may be necessary to improve the tensile properties of engineered constructs to match that of the native tissue.

Collectively, the results of this study suggest that ECM deposition by chondrocytes and MSCs can improve the tensile properties of engineered constructs. However, the low tensile properties achieved under these free swelling conditions are a significant impediment to load-bearing use. These limitations correlate with the poor construct collagen content and the overall lack of ECM organization. Engineering methods that borrow from developmental concepts of remodeling and physiologic use may be necessary to improve construct tensile properties and enable their load bearing capacity upon implantation.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (RO3 AR053668) and a Graduate Research Fellowship from the National Science Foundation (AHH). The authors also gratefully acknowledge Mr. Nandan Nerurkar for his assistance in texture correlation analysis.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ateshian GA, Hung CT. Patellofemoral joint biomechanics and tissue engineering. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005:81–90. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000171542.53342.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guilak F, Sah RL, Setton LA. Physical regulation of cartilage metabolism. In: Mow VC, Hayes WC, editors. Basic orthopaedic biomechanics. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1997. pp. 179–207. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mow VC, Ratcliffe A, Chern KY, Kelly MA. Structure and function relationships of the menisci of the knee. In: Mow VC, Arnoczky SP, Jackson DW, editors. Knee meniscus: basic and clinical foundations. New York: Raven Press, Ltd; 1992. pp. 37–57. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buckwalter JA, Martin J, Mankin HJ. Synovial joint degeneration and the syndrome of osteoarthritis. Instr Course Lect. 2000;49:481–489. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hunziker EB. Articular cartilage repair: are the intrinsic biological constraints undermining this process insuperable? Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 1999;7:15–28. doi: 10.1053/joca.1998.0159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vunjak-Novakovic G, Martin I, Obradovic B, Treppo S, Grodzinsky AJ, Langer R, et al. Bioreactor cultivation conditions modulate the composition and mechanical properties of tissue-engineered cartilage. J Orthop Res. 1999;17:130–138. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100170119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li WJ, Jiang YJ, Tuan RS. Chondrocyte phenotype in engineered fibrous matrix is regulated by fiber size. Tissue Eng. 2006;12:1775–1785. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.1775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pei M, Solchaga LA, Seidel J, Zeng L, Vunjak-Novakovic G, Caplan AI, et al. Bioreactors mediate the effectiveness of tissue engineering scaffolds. Faseb J. 2002;16:1691–1694. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0083fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chung C, Mesa J, Randolph MA, Yaremchuk M, Burdick JA. Influence of gel properties on neocartilage formation by auricular chondrocytes photoencapsulated in hyaluronic acid networks. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2006;77:518–525. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mauck RL, Wang CC, Oswald ES, Ateshian GA, Hung CT. The role of cell seeding density and nutrient supply for articular cartilage tissue engineering with deformational loading. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2003;11:879–890. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2003.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chang SC, Rowley JA, Tobias G, Genes NG, Roy AK, Mooney DJ, et al. Injection molding of chondrocyte/alginate constructs in the shape of facial implants. J Biomed Mater Res. 2001;55:503–511. doi: 10.1002/1097-4636(20010615)55:4<503::aid-jbm1043>3.0.co;2-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elisseeff J. Injectable cartilage tissue engineering. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2004;4:1849–1859. doi: 10.1517/14712598.4.12.1849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hunter CJ, Mouw JK, Levenston ME. Oscillatory compression inhibits matrix accumulation by chondrocytes in fibrin gel culture. Trans. ORS. 2002;27:136. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kisiday J, Jin M, Kurz B, Hung H, Semino C, Zhang S, et al. Self-assembling peptide hydrogel fosters chondrocyte extracellular matrix production and cell division: implications for cartilage tissue repair. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:9996–10001. doi: 10.1073/pnas.142309999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnstone B, Hering TM, Caplan AI, Goldberg VM, Yoo JU. In vitro chondrogenesis of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal progenitor cells. Exp Cell Res. 1998;238:265–272. doi: 10.1006/excr.1997.3858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Awad HA, Wickham MQ, Leddy HA, Gimble JM, Guilak F. Chondrogenic differentiation of adipose-derived adult stem cells in agarose, alginate, and gelatin scaffolds. Biomaterials. 2004;25:3211–3222. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.10.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mauck RL, Yuan X, Tuan RS. Chondrogenic differentiation and functional maturation of bovine mesenchymal stem cells in long-term agarose culture. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2006;14:179–189. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2005.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li WJ, Tuli R, Huang X, Laquerriere P, Tuan RS. Multilineage differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells in a three-dimensional nanofibrous scaffold. Biomaterials. 2005;26:5158–5166. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Angele P, Kujat R, Nerlich M, Yoo J, Goldberg V, Johnstone B. Engineering of osteochondral tissue with bone marrow mesenchymal progenitor cells in a derivatized hyaluronan-gelatin composite sponge. Tissue Eng. 1999;5:545–554. doi: 10.1089/ten.1999.5.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Williams CG, Kim TK, Taboas A, Malik A, Manson P, Elisseeff J. In vitro chondrogenesis of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells in a photopolymerizing hydrogel. Tissue Eng. 2003;9:679–688. doi: 10.1089/107632703768247377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang CY, Reuben PM, D'Ippolito G, Schiller PC, Cheung HS. Chondrogenesis of human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells in agarose culture. Anat Rec A Discov Mol Cell Evol Biol. 2004;278:428–436. doi: 10.1002/ar.a.20010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mauck RL, Seyhan SL, Ateshian GA, Hung CT. Influence of seeding density and dynamic deformational loading on the developing structure/function relationships of chondrocyte-seeded agarose hydrogels. Ann Biomed Eng. 2002;30:1046–1056. doi: 10.1114/1.1512676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Puelacher WC, Kim SW, Vacanti JP, Schloo B, Mooney D, Vacanti CA. Tissue-engineered growth of cartilage: the effect of varying the concentration of chondrocytes seeded onto synthetic polymer matrices. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1994;23:49–53. doi: 10.1016/s0901-5027(05)80328-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pei M, Seidel J, Vunjak-Novakovic G, Freed LE. Growth factors for sequential cellular de- and re-differentiation in tissue engineering. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;294:149–154. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(02)00439-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gooch KJ, Blunk T, Courter DL, Sieminski AL, Bursac PM, Vunjak-Novakovic G, et al. IGF-I and mechanical environment interact to modulate engineered cartilage development. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;286:909–915. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mauck RL, Nicoll SB, Seyhan SL, Ateshian GA, Hung CT. Synergistic action of growth factors and dynamic loading for articular cartilage tissue engineering. Tissue Eng. 2003;9:597–611. doi: 10.1089/107632703768247304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Byers BA, Mauck RL, Chiang RL, Tuan RS. Temporal exposure of TGF-beta3 under serum-free conditions enhances biomechancial and biochemical maturation of tissue-engineered cartilage. Trans ORS. 2006;31:43. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2007.0222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Freed LE, Langer R, Martin I, Pellis NR, Vunjak-Novakovic G. Tissue engineering of cartilage in space. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:13885–13890. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.25.13885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chahine NO, Wang CC, Hung CT, Ateshian GA. Anisotropic strain-dependent material properties of bovine articular cartilage in the transitional range from tension to compression. J Biomech. 2004;37:1251–1261. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2003.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kempson GE. Age-related changes in the tensile properties of human articular cartilage: a comparative study between the femoral head of the hip joint and the talus of the ankle joint. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1991;1075:223–230. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(91)90270-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Williamson AK, Chen AC, Masuda K, Thonar EJ, Sah RL. Tensile mechanical properties of bovine articular cartilage: variations with growth and relationships to collagen network components. J Orthop Res. 2003;21:872–880. doi: 10.1016/S0736-0266(03)00030-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Charlebois M, McKee MD, Buschmann MD. Nonlinear tensile properties of bovine articular cartilage and their variation with age and depth. J Biomech Eng. 2004;126:129–137. doi: 10.1115/1.1688771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huang CY, Mow VC, Ateshian GA. The role of flow-independent viscoelasticity in the biphasic tensile and compressive responses of articular cartilage. J Biomech Eng. 2001;123:410–417. doi: 10.1115/1.1392316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huang CY, Stankiewicz A, Ateshian GA, Mow VC. Anisotropy, inhomogeneity, and tension-compression nonlinearity of human glenohumeral cartilage in finite deformation. J Biomech. 2005;38:799–809. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2004.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Soltz MA, Ateshian GA. A Conewise Linear Elasticity mixture model for the analysis of tension-compression nonlinearity in articular cartilage. J Biomech Eng. 2000;122:576–586. doi: 10.1115/1.1324669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Soulhat J, Buschmann MD, Shirazi-Adl A. A fibril-network-reinforced biphasic model of cartilage in unconfined compression. J Biomech Eng. 1999;121:340–347. doi: 10.1115/1.2798330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Elliott DM, Guilak F, Vail TP, Wang JY, Setton LA. Tensile properties of articular cartilage are altered by meniscectomy in a canine model of osteoarthritis. J Orthop Res. 1999;17:503–508. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100170407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lima EG, Bian L, Ng KW, Mauck RL, Byers BA, Tuan RS, et al. The beneficial effect of delayed compressive loading on tissue-engineered cartilage constructs cultured with TGF-beta3. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2007.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Farndale RW, Buttle DJ, Barrett AJ. Improved quantitation and discrimination of sulphated glycosaminoglycans by use of dimethylmethylene blue. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1986;883:173–177. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(86)90306-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stegemann H, Stalder K. Determination of hydroxyproline. Clin Chim Acta. 1967;18:267–273. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(67)90167-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Normand V, Lootens DL, Amici E, Plucknett KP, Aymard P. New insight into agarose gel mechanical properties. Biomacromolecules. 2000;1:730–738. doi: 10.1021/bm005583j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Williams GM, Klein TJ, Sah RL. Cell density alters matrix accumulation in two distinct fractions and the mechanical integrity of alginate-chondrocyte constructs. Acta Biomater. 2005;1:625–633. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2005.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Quinn TM, Schmid P, Hunziker EB, Grodzinsky AJ. Proteoglycan deposition around chondrocytes in agarose culture: construction of a physical and biological interface for mechanotransduction in cartilage. Biorheology. 2002;39:27–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Burdick JA, Philpott LM, Anseth KS. Synthesis and characterization of tetrafunctional lactic acid oligomers: A potential in situ forming degradable orthopaedic biomaterial. Journal of Polymer Science Part a-Polymer Chemistry. 2001;39:683–692. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Park Y, Lutolf MP, Hubbell JA, Hunziker EB, Wong M. Bovine primary chondrocyte culture in synthetic matrix metalloproteinase-sensitive poly(ethylene glycol)-based hydrogels as a scaffold for cartilage repair. Tissue Eng. 2004;10:515–522. doi: 10.1089/107632704323061870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Burdick JA, Chung C, Jia X, Randolph MA, Langer R. Controlled degradation and mechanical behavior of photopolymerized hyaluronic acid networks. Biomacromolecules. 2005;6:386–391. doi: 10.1021/bm049508a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li Q, Williams CG, Sun DD, Wang J, Leong K, Elisseeff JH. Photocrosslinkable polysaccharides based on chondroitin sulfate. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2004;68:28–33. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.20007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Archer CW, Dowthwaite GP, Francis-West PH. Development of synovial joints. Birth Def Res (Part C) 2003;69:144–155. doi: 10.1002/bdrc.10015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Athanasiou KA, Zhu CF, Wang X, Agrawal CM. Effects of aging and dietary restriction on the structural integrity of rat articular cartilage. Ann Biomed Eng. 2000;28:143–149. doi: 10.1114/1.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kempson GE. Relationship between the tensile properties of articular cartilage from the human knee and age. Ann Rheum Dis. 1982;41:508–511. doi: 10.1136/ard.41.5.508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Williamson AK, Chen AC, Sah RL. Compressive properties and function-composition relationships of developing bovine articular cartilage. J Orthop Res. 2001;19:1113–1121. doi: 10.1016/S0736-0266(01)00052-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Williamson AK, Masuda K, Thonar EJ, Sah RL. Growth of immature articular cartilage in vitro: correlated variation of tensile biomechanical and collagen network properties. Tiss Eng. 2003;9:625–634. doi: 10.1089/107632703768247322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fedewa MM, Oegema TR, Jr, Schwartz MH, MacLeod A, Lewis JL. Chondrocytes in culture produce a mechanically functional tissue. J Orthop Res. 1998;16:227–236. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100160210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gemmiti CV, Guldberg RE. Fluid flow increases type II collagen deposition and tensile mechanical properties in bioreactor-grown tissue-engineered cartilage. Tissue Eng. 2006;12:469–479. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Aufderheide AC, Athanasiou KA. Assessment of a Bovine Co-culture, Scaffold-Free Method for Growing Meniscus-Shaped Constructs. Tissue Eng. 2007;13:2195–2205. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.0291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gratz KR, Wong VW, Chen AC, Fortier LA, Nixon AJ, Sah RL. Biomechanical assessment of tissue retrieved after in vivo cartilage defect repair: tensile modulus of repair tissue and integration with host cartilage. J Biomech. 2006;39:138–146. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2004.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]