Abstract

The purpose of this study was to develop and validate a screening method based on scintillation probes for the simultaneous evaluation of in vivo growth factor release profiles of multiple implants in the same animal. First, we characterized the scintillation probes in a series of in vitro experiments to optimize the accuracy of the measurement setup. The scintillation probes were found to have a strong geometric dependence and experience saturation effects at high activities. In vitro simulation of 4 subcutaneous limb implants in a rat showed minimal interference of surrounding implants on local measurements at close to parallel positioning of the probes. These characteristics were taken into consideration for the design of the probe setup and in vivo experiment. The measurement setup was then validated in a rat subcutaneous implantation model using 4 different sustained release carriers loaded with 125I-BMP-2 per animal. The implants were removed after 42 or 84 days of implantation, for comparison of the non-invasive method to ex-vivo radioisotope counting. The non-invasive method demonstrated a good correlation with the ex-vivo counting method at both time-points of all 4 carriers. Overall, this study showed that scintillation probes could be successfully used for paired measurement of 4 release profiles with minimal interference of the surrounding implants, and may find use as non-invasive screening tools for various drug delivery applications.

Keywords: Controlled drug delivery, non-invasive screening, scintillation detector, radiolabelled growth factor, method validation

Introduction

Over the past decades, the role of bioactive molecules in regenerative medicine has increased tremendously. As a result of modern genomic and proteomic technologies, increasing numbers of proteins are becoming available as potential candidates for the modulation of cellular behavior and tissue response. However, since most of these proteins have short in vivo half lives and exert their effect by acting locally on cells, they require a carrier system for localized and sustained delivery at the target site. Consequently, integration of drug delivery systems into biomaterial design has become a fundamental aspect of regenerative medicine.

Many biodegradable delivery systems have been developed for the controlled release of bioactive proteins. Since the biological responses to these proteins can be time- and concentration-dependent, the release profiles of these delivery systems are of crucial importance to their application. Most studies of newly developed carriers only characterized their in vitro protein release profiles. However, due to the differences between the in vitro and in vivo environment, the release profiles can change significantly upon implantation.[1–4] Therefore, new and reliable methods are needed to measure in vivo release profiles.

An effective method for determining in vivo pharmacokinetic profiles is provided by labeling proteins with radioactive tracers.[1, 5–9] This allows quantification of protein release by correlating the remaining activity of the tracer in the implant to the amount of protein. The most accurate method for determining tracer activity is by conventional ex-vivo counting using the gamma counter. This ex vivo counting method is considered the gold standard because of the high spatial resolution and quantitative information, which allows the implantation of multiple implants per animal. Furthermore, the high sensitivity of the gamma counters allows the use of low isotope quantities.[10–12] However, ex-vivo quantification does not allow sequential measurements of the same implant or animal in time. Moreover, since the animals need to be sacrificed for the measurements, these pharmacokinetic studies often require large numbers of animals to obtain detailed release profiles.[10, 13–16] Therefore, non-invasive methods that significantly reduce sample size and allow sequential measurements are being explored for determining release profiles.[2, 3, 17–21]

A feasible option for non-invasive determination of isotope content is the use of scintillation probes, which are commonly used devices to measure ionizing radiation. In nuclear medicine, they have been used for a long time to determine the iodine uptake of the thyroid to diagnose diseases of the thyroid gland. A recent validation study of the scintillation probe for non-invasive release measurement showed that it could also be reliably used as a screening tool for determining a single release profile of bioactive molecules.[17] In this study, we validated this non-invasive screening method for the simultaneous evaluation of multiple in vivo release profiles by comparing it with the ex-vivo quantification method. The non-invasive method was validated in an ectopic implantation model in rats using four sustained release carriers delivering bone morphogenetic protein-2 (BMP-2). The in vitro and in vivo bioactivity of the released BMP-2 from these four carriers is reported in a separate manuscript.[22]

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental design

First, the influence of the source-to-probe distance and counting rate linearity were characterized to optimize the accuracy of the measurement setup. Since the in vivo situation rarely allows perfect parallel positioning of the probes, we also determined the interference of multiple sources on the background signal at increasing deviations from parallel probe positioning (Figure 1). The scintillation probe setup was then validated in an ectopic implantation model in 20 rats using four different local release carriers containing radioiodinated recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 (BMP-2, Medtronic Sofamor Danek, MN). Release profiles as well as the excretion and blood profiles were determined over a period of 84 days. The implants were removed after 42 and 84 days of implantation for the comparison of the non-invasive method to the ex-vivo counting method. Post-mortem, several organs and the tissue surrounding the implant were evaluated for radioactivity to rule out local and systemic 125I accumulation.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the non-invasive measurement method in the rat. The active portion of the measurement setup consisted of scintillation probes (A) containing a sodium iodide scintillator (B) were collimated with a hollow tube (C) and wrapped in leaded tape to determine the activity of subcutaneous implanted release vehicles (D) over time. The implant-toprobe distance (1), the detector linearity (2) and interference of multiple sources at different probe angles (3) were characterized prior to the in vivo experiment.

2.2. Detectors

The measurement setup consisted of four scintillation probes (Model 44-3 low energy gamma scintillator, Ludlum Measurements Inc., TX). The active portion of these probes contained a cylindrical sodium iodide (Tl) scintillator with a diameter of 2.5 cm and a thickness of 1 mm. The four probes were fixed in a frame and connected to a digital scaler with an adjustable timer (Model 1000 scaler, Ludlum Measurements Inc.). The probe was collimated with a hollow tube with a diameter of 2.6 cm and both the tube and active portion of the detector were wrapped in leaded tape. The high voltage of the detectors was adjusted to 0.8 (± 0.1) kV resulting in 2.9 × 105 (± 0.08 × 105) cpm for a 5.3 µCi 125I point-source at a distance of 3 cm and a counting efficiency of 2.5 (± 0.1) %.

The ex vivo measurements were done using a gamma counter (Minaxi Auto Gamma 5000 series gamma counter, Packard Instruments, Downers Grove, IL) and radioisotope dose calibrator (CRC-5, Capintech. Montvale, NJ). The gamma counter and dose calibrator were calibrated using 125I standards provided by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST).

2.3. In vitro calibration of experimental setup

The influence of source-to-probe distance, counting rate linearity, and interference of surrounding sources were characterized using 125I sources with different activities (Figure 1). The sources were created by pipetting 1 to 50 µl of a Na125I solution on absorbing wipes. The wipes were air-dried for 48 hrs before use and their activity was determined using the gamma counter and/or the dose calibrator. The influence of the implant-to-probe distance was determined with 0.4 and 4.0 µCi sources at increasing distances. The geometric efficiency was calculated by normalizing the counts to the estimated number of photons emitted by the source. For the other experiments we used a consistent distance of 3 cm.

The counting rate linearity of each detector was evaluated by measuring the counts of 20 sources with activities varying from 0.3 to 18 µCi. The interference of surrounding radioisotope sources on a local measurement was determined with the probes placed at the corners of a 4.5 by 9 cm rectangle. This rectangle was based on measurements on cadaver rats which showed an estimated minimal distance of 4.5 cm between the left and right leg and a distance of 9 cm between front and hind leg. The background of each detector was measured in the presence and in the absence of a single 6.3 µCi radioactive source at one of the corners of the rectangle. The measurements were repeated with the source in each of the 4 corners and at angles of 0, 9, 18, 27 and 34 degrees of deviation from parallel placement of the probes. The background counts were normalized to the detector counts of the 6.3 µCi source at each position and expressed as percentage.

2.4. BMP-2 iodination

Recombinant human BMP-2 was radioiodinated with 125I using Iodo-Gen® precoated test tubes according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Briefly, 100 µl of a 1.43 mg/ml BMP-2 solution, 20 µl of a 0.1 M NaOH solution and 2 mCi Na125I were added to a 1,3,4,6-tetrachloro-3α,6α-diphenyl glycouril-coated glass test tube. The mixture was incubated for 15 minutes at room temperature with gentle shaking. To separate radiolabeled protein from free radioactive iodine, the solution was dialyzed (cutoff 10 kDa) for 24 hrs with 3 times media change against a buffer containing 5 mM glutamic acid, 2.5 wt% glycine, 0.5% sucrose and 0.01% Tween 80 (pH 4.5). The dialysis fractions of 3 radioiodination procedures were pooled and concentrated to a final concentration of 9.8 µCi/µl with a Vivaspin device (cutoff 10 kDa). Trichloroacetic acid (TCA) precipitation of the final 125I-BMP-2 solution indicated 99% precipitable counts.

2.5. Implants

The selection of the local delivery vehicles used in this study, gelatin, poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) and poly(propylene fumarate), was based on previous work demonstrating their capability of binding BMP-2 or extending protein release.[3, 23–30] The materials were combined into composite formulations in order to further extend BMP-2 release over a prolonged period of time. Four local release carriers were used for the in vivo validation of the measurement setup, consisting of: A) a gelatin hydrogel, B) poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) microspheres in a gelatin hydrogel, C) PLGA microspheres in a poly(propylene fumarate) (PPF) scaffold and D) PLGA microspheres in a PPF scaffold surrounded by a gelatin hydrogel. The implants were loaded with the 125I-BMP2/BMP-2 mixture with a hot:cold ratio of 1:8. The equations 1 and 2 were used to determine the initial 125I-BMP-2 activity of the implants:

| Equation 1 |

| Equation 2 |

In these equations, the values for background activity and detector efficiency were obtained from the ex-vivo experiments. The skin shielding was determined on fresh cadaver rats using a dummy implant. The 125I half-life (T½ = 60.1 days) was obtained from literature.

The gelatin hydrogels were prepared by chemically cross-linking a 10% filter-sterilized gelatin solution with 0.2% glutaraldehyde according to a previously described method.[15, 16] The hydrogels were cross-linked for 6 hrs at 4°C, which was followed by a 1 hr blocking period of the residual aldehyde groups in a 100 mM glycine solution. The resulting hydrogels were impregnated with 5 µl of the concentrated BMP-2 solution the day before implantation. The microspheres/hydrogel composite (implant B) or the microsphere/PPF/hydrogel composite (implant D) were created by combining PLGA microspheres or a microsphere/PPF composite with the gelatin hydrogel just before cross-linking.

The PLGA (50/50 DL, Mw 23000, Medisorb, Alkemers, Cincinnati, OH) microspheres loaded with BMP-2 were fabricated using a double emulsion-solvent extraction technique as previously described.[27] The final product consisted of spherical particles with a smooth surface. Based on the 125I counts before and after the microsphere fabrication procedure, the entrapment efficiency of BMP-2 was 84 % or 1.4 µg/mg PLGA microspheres.

Poly(propylene fumarate) (Mn = 2900) was synthesized using a two-step procedure as previously described.[31] PPF (1g) was crosslinked using N-vinyl pyrrolidinone (0.5 ml, NVP, Acros, Pittsburgh, PA) as cross-linker and bis(2,4,6-trimethylbenzoyl) phenylphosphine oxide (5 mg, BAPO, Ciba Specialty Chemicals, Tarrytown, NY) as photo-initiator. The PPF/NVP/BAPO paste was combined with 55 wt% microspheres, forced into a glass cylindrical mold (Ø 1.6 mm) and placed under UV-light for 30 minutes for photo-crosslinking. The cross-linked cylinders were sectioned into 6 mm long rods and sterilized by ethanol evaporation. The implants were stored in sterile microcentrifuge tubes at −20 °C until use. For the ex-vivo counting method, the activity of the microcentrifuge tubes was measured before and after the surgical procedure to determine the implanted activity.

2.6. Subcutaneous implantation and in vivo release measurement

A total of twenty male 12-week-old Harlan Sprague Dawley rats (weight 317 (± 8) g) were used for the experiment, according to a protocol approved by the local animal care committee. The rats were allowed to acclimatize for 1 week before the start of the experiment. Anesthesia was provided with an intramuscular injection of a ketamine/xylazine mixture (45/10 mg/kg). Prior to surgery, the rats received an antibiotic prophylaxis of sulfonamide (40 mg/kg) and surgical sites were shaved and disinfected. Each rat received one 125I-BMP-2 loaded implant in a subcutaneous pocket in each of the 4 legs and 2 non-radioactive implants (negative controls for reference 22) in a subcutaneous pocket in the lumbar area. The subcutaneous pockets were created on the dorsal site of the limb distal to the elbow and knee by blunt dissection through a 0.5 cm skin incision and filled with one implant according to a randomized scheme. The pockets were closed using non-resorbable nylon sutures.

Directly after closure of the wounds, the local activity of the implants was measured using the probe setup. The four probes were placed on top of the skin at the implantation sites and the signal was measured of two consecutive 1-minute periods. The rat was horizontally rotated 180° under the frame and the measurements were repeated with different detectors. The measurements were repeated weekly under ketamine/xylazine sedation (20/5 mg/kg). To determine the retention profile, the measurements were corrected for radioactive decay and background activity and expressed as percentage of the implanted dose. At the end of the 12 week follow up period, the linearity of each detector was re-evaluated to assure a stabile calibration curve.

During the follow up period, ten animals were placed in metabolic cages for a period of 24 hours before the release measurements to collect urine and feces samples. At the time of the release measurements, approximately 400 µl of blood was collected from the tail vein of 5 rats which were housed in the metabolic cages. The radioactivity of the urine, feces and blood samples was determined using the gamma counter and the total volumes of the urine and blood collection were recorded to determine the 125I urine clearance using the equation 3:

| Equation 3 |

2.7. Post mortem sample acquisition and ex vivo counting

After 6 and 12 weeks, the implants were excised and fixed in phosphate buffered saline (137 mM NaCl, 10 mM phosphate, 2.7 mM KCl) containing 1.5% glutaraldehyde. The fibrous capsule and part of the overlying skin was not removed because they were integrated with the degrading implant. The thyroid, stomach, kidneys, liver, spleen, and left femur were excised to evaluate the 125I tissue distribution. The tissue surrounding the implant at the left hind limb was also harvested to determine the local 125I accumulation. The implants and tissues were counted ex vivo using the gamma counter.

2.8. Statistical analysis

The in vitro data are expressed as average ± standard deviation (SD) of 3 consecutive 1-minute measurements of 4 detectors without subtraction of the background. The in vivo data are reported as means ± SD for n = 5 (blood measurements) and n = 10 (all other in vivo and ex-vivo measurements). Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to determine the effect of probe-to-source distance on the geometric efficiency per activity and the comparison of the interference of multiple sources and the comparison of the implant types. Bonferroni-corrected post-hoc tests were performed to analyze the differences between the groups. Linear regression analysis was applied to determine the relation between the source activity and the scintillation probe counts. A t-test was performed to detect differences between implant retentions measured by the non-invasive and ex-vivo method. All tests were performed using SPSS (version 13.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) and the level of significance was set at p =0.05.

3. Results

3.1 Ex vivo calibration of experimental setup

The source-to-probe distance, counting rate linearity and interference of surrounding sources were characterized prior to the in vivo experiments to optimize the accuracy of the probe setup. As shown in figure 2A, the source-to-probe distance significantly affected the geometric efficiency (p<0.001). The source activity and the scintillation probe counts showed excellent linear relations in the range from 0 to 7.8 µCi with a squared correlation coefficient (R2) between 0.991 and 0.999 and a regression coefficient β between 0.995 and 0.999 (Figure 2B). Further increase in activity resulted in a decrease of the linear relation. Analysis of the linear relation at the end of the in vivo experiment showed that the calibration curve remained stable over the 12 week follow up period. The average background of the detectors was 250 ± 50 cpm in the absence of radioactive sources. The background significantly increased 1.5 fold in the presence of a 6.3 µCi source, which resulted in a normalized background of 0.17 ± 0.02 % of the source (Figure 2C). An angular deviation from parallel probe positioning had no significant effect on the backgrounds of the opposing front/hind limbs. The background of the contra-lateral limb significantly increased at detector angles higher than 9 degrees pointing towards each other.

Figure 2.

In vitro characterization of important parameters influencing the accuracy of the probe setup. The investigated parameters were (A) the relation between probe-to-source distance and geometric efficiency, (B) the counting rate linearity of the individual probes, and (C) the interference of a surrounding source at different angular deviations from parallel probe positioning. The counting rate linearity and the interference of a surrounding source were determined at a distance of 3 cm between the source and the detector.

3.2 Implants

The counting threshold was set at 4 times the background signal to minimize the interference of surrounding implants with measurement of the release profiles. Based on a background activity of ± 300 cpm, a detector efficiency of 2.7 %, a skin shielding of 5.8 ± 1.7% and equations 1 and 2 proposed in the Materials and Methods, the implants required an activity of approximately 5.6 µCi to be able to detect 1.0 % 125I-BMP-2 retention after 12 weeks of radioactive decay with an activity above the set threshold. The actual activity of implants after fabrication was 6.0 ± 0.5, 3.7 ± 0.6, 5.6 ± 0.5 and 5.8 ± 0.4 µCi for implants A, B, C and D, respectively. The corresponding variation coefficients for the ex-vivo measurements before implantation were 10.3, 16.3, 9.3 and 6.4 %. During the implantation procedure, 3.5 ± 5.2, 0.24 ± 0.42, 0.021 ± 0.038 and 0.10 ± 0.13 % of the activity was lost. The variation coefficient of the non-invasive measurements just after implantation were 27.4, 19.6, 9.6 and 8.1 %.

3.3 In vivo validation

During follow-up, one rat was lost on day 56 during sedation for the release measurement, most likely due to an overdose of anesthetics. One implant was lost in another rat since it was removed by the animal from a subcutaneous pocket in the hind limb at the end of the first week of follow-up. All the other animals remained healthy during the experiment without any signs of complications during wound healing. A total of 4 implants, all placed in the front limbs of the first 3 operated rats, was excluded from the analysis. These implants were placed too proximal in the limbs, which resulted in incorrect day 0 measurements due to difficult probe placements. This problem was recognized immediately and did not occur in subsequent animals.

No other problems were encountered during the release measurements. The retention 125I-BMP2 profiles that were obtained with the scintillation probes are shown in figure 3. Implant A showed a burst release of 92.2 (± 4.4) % of the BMP-2 within the first 14 days of implantation. After 63 days of release, the activity of implant A dropped below the threshold of 1.0% retention. The other scaffolds showed no initial burst release but a more sustained release over time.

Figure 3.

125I-BMP-2 release profiles from four different implants obtained by the non-invasive measurement method. The implants consisted of (A) BMP-2 loaded gelatin hydrogels, (B) BMP-2 loaded microspheres in a gelatin hydrogel, (C) BMP-2 loaded microspheres in a PPF scaffold and (D) BMP-2 loaded microspheres in a PPF scaffold surrounded by a gelatin hydrogel.

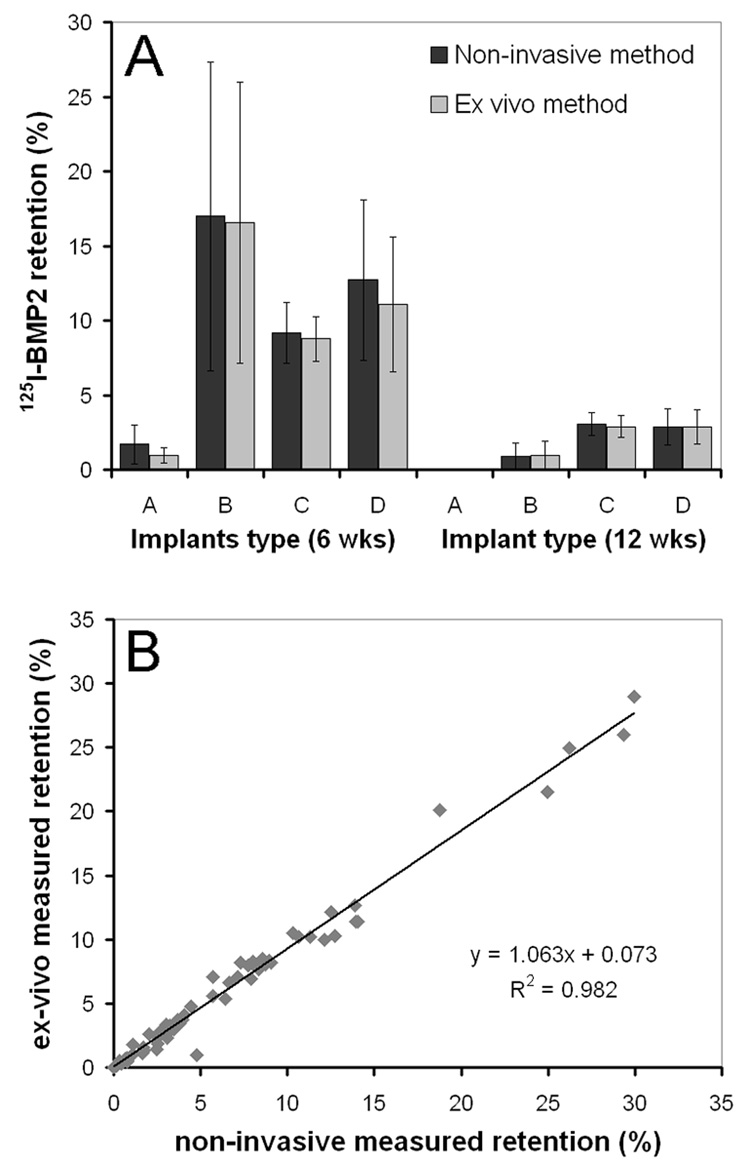

The scintillation probe setup was validated by comparing the non-invasive measurements to the ex vivo measurements at 6 and 12 weeks of release (Figure 4A). The implants were excised from the surrounding tissue for ex vivo counting; however the fibrous capsule was not removed because it was well integrated with the degrading implant. The retention of implant A at 12 weeks (0.1 ± 0.2 % by the ex vivo method and 0.2 ± 0.2 % by the non-invasive methods) was excluded from this validation, because these values were below the threshold. Comparison of both methods showed a slightly, not statistically significant increased data dispersion of the non-invasive method which resulted in an overestimation of 0.7 (± 1.2) % and 0.05 (± 0.29) % after 6 and 12 weeks of release, respectively. The measurements obtained by both methods showed an R2 of 0.982 and an excellent intra-class correlation coefficient of 0.993 (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Average 125I-BMP-2 retention in the 4 implants after 6 and 12 weeks of implantation measured using the non-invasive and ex-vivo method (A) and the correlation between the two methods (B). The implants consisted of (A) BMP-2 loaded gelatin hydrogels, (B) BMP-2 loaded microspheres in a gelatin hydrogel, (C) BMP-2 loaded microspheres in a PPF scaffold and (D) BMP-2 loaded microspheres in a PPF scaffold surrounded by a gelatin hydrogel.

Both the blood and excretion profiles correlated well with the 125I-BMP-2 release profile from the implants and showed two peaks at 3 and 21 days that corresponded with the major releases of implant A and implants B, C & D, respectively (Figure 5). The 125I urine clearance over the 84 day period was 0.16 (± 0.8) ml/min. The tissue distribution after 6 and 12 weeks of implantation is shown in Table 2.

Figure 5.

125I counts in the blood (A) and in 24 hour urine and feces excretions (B) after 125IBMP- 2 release from the 4 subcutaneously placed implants.

4. Discussion

In this study, a scintillation probe setup for simultaneous screening of multiple in vivo protein release profiles was validated. During the design of the experimental set-up, the implant-to-probe distance was identified as the most important factor influencing the accuracy of the measurement setup (Figure 2A). Theoretically, the correlation between the implant-to-probe distance and the geometric efficiency obeys the inverse square law.[32] Therefore, small distance changes with a short collimator will have a larger effect on the acquired counts compared to a longer collimator. To balance the number of acquired counts and minimize the influence of small distance deviations, a 3-cm collimator was chosen for the experimental setup. The larger distance between the probe and the radioactive source potentially decreased data dispersion. However, it also required a higher amount of radioactivity to compensate for the loss of counting efficiency with the increased distance.

Another important parameter that affects the accuracy of the probe setup is the linear correlation between the activity and the number of acquired counts. This linear correlation is mainly determined by the intrinsic properties of the scintillation probes and must be without interference of dead-time effects.[32] The dead-time effects appear as the probe reaches its saturation level, resulting in missing counts at close range (Figure 2A) and a non-linear activity-count relation of high activity sources (Figure 2B). The linear range of the probes, which remained stable, was used for the in vivo experiment. Although adjustment of the high voltage of the detectors resulted in approximately similar counts at the same activity, the acquired counts still varied 2.7 % at 5.3 µCi. Therefore two probes were used for the in vivo measurements in case one of the detectors would fail to show a stable linear relation over the follow up period. Although not included in this study, additional probe controls, repetitions of probe positioning and probe measurements can be investigated depending on the sedation time of the animals.

Although implantation of multiple isotropic radiating sources induces the risk of cross-detection of surrounding implants, the interference in our ex-vivo measurements was minimal at near parallel positioning of the detectors (Figure 2C). In the in vivo set up, maximizing the distance between the implants by creating the pockets as distal as possible allowed almost parallel positioning of the probes and resulted in minimal interference of the surrounding implants.

Until recently, few studies have characterized in vivo sustained release profiles from local protein carriers and even fewer publications are dealing with non-invasive detection methods. Recent studies investigating the use of a single-head gamma camera for simultaneous evaluation of implant release profiles suggest that the interference of surrounding implants can result in a 12 to 16% overestimation of a non-invasive method.[2, 19] Compared to a gamma camera setup, collimated scintillation probes used in the present study allow good shielding of individual implants. The facilitated shielding helped decrease the overestimation of the scintillation probe method to 0.7 (± 1.2) % after 6 weeks of implantation.

During the validation by Delgado of a scintillation probe setup with a single injectable implant in a rat femur model, higher variation coefficients were seen just after implantation for the non invasive method compared to the ex-vivo counting method.[17] This was attributed to an inconsistent geometry during the measurements which was inherent to the implant injection method employed in that study. In our study, the difference between the variation coefficients at implantation varied between the implants. At the subcutaneous implantation site, the non-hydrated microsphere/PPF implants showed a minimal difference between the variation coefficients of the measurements with the two different methods. However, the 90% aqueous gelatin implants had a much larger difference between the variation coefficients. This is likely the result of a higher loss of implant activity during implantation and a rapid initial burst release after implantation. Consequently, non-invasive methods might be less suitable for measuring implant release profiles of implants with a significant protein loss during implantation and rapid burst release after implantation.

One of the limitations of non-invasive measurement techniques is the possibility of interference of systemic accumulation (e.g. 125I thyroid accumulation interfering with the front limb measurements) or local accumulations (125I connective tissue accumulation around the implant) with the measurement of the radioactive isotope in the delivery vehicle. Unlike other non-invasive measurement methods such as gamma cameras or SPECT scanners, scintillation detectors do not provide images that can show systemic isotope accumulations. Therefore we monitored the isotope clearance and studied the organ/tissue distribution upon sacrifice. The isotope excretion, blood and tissue distribution profiles indicated a rapid urine clearance and minimal organ accumulation. Previous studies have investigated the local accumulation of the isotope and showed a minimal accumulation of the growth factor in the fibrous capsule surrounding the implant.[2, 19, 21] Furthermore, after subcutaneous injection of a carrier-free 125I-BMP-2 solution, the growth factor was rapidly cleared from the injection site with a T½ of 0.3 day.[2] Therefore, the interference of local isotope accumulation on the measurements of the BMP-2 release profiles is likely to be minimal.

During in vivo validation of the measurement setup, implants with a high binding capacity for BMP-2 were used in order to extend its release over a prolonged period of time. The different material and implant characteristics resulted in different losses of implant activity upon implantation and different release profiles. During the 12 week follow up period, all 125I-BMP-2 loaded implants showed bone formation.[22] Due to the small amount of newly formed bone and the large animal variability of the release profile, the effect of bone formation on the release profile is expected to be limited in this study.

Overall, this study shows that scintillation probes can be successfully used as non-invasive screenings tool for simultaneous evaluation of in vivo protein release profiles of multiple implants in the same animal. By applying basic principles of physics (collimation, shielding and maximizing the inter-implant distance), the scintillation probe can be reliably used for paired measurement of four release profiles with minimal interference of the surrounding implants. This new method is available to every research laboratory that has access to facilities working with radioactive isotopes. Furthermore, the paired evaluation of release profiles in the same animal requires fewer animals and results in less radioactive waste. The screening method can be easily applied to determine the local release profiles of other growth factors or drugs; however 125I-drug injection studies (without the carrier), clearance monitoring and organ accumulation monitoring need to be considered to provide additional information on the local or systemic accumulation of the radioactive tracer.

Table 1.

Percent 125I distribution of the initial implanted activity upon sacrifice at days 42 and 84.

| Implants/Tissue | Day 42 | Day 84 |

|---|---|---|

| Implants | 8.7 (± 2.5) | 0.97 (± 0.43) |

| Thyroid | 0.75 (± 0.14) | 0.29 (± 0.15) |

| Stomach | 0.042 (± 0.021) | < 0.005 |

| Kidney | 0.023 (± 0.003) | < 0.005 |

| Liver | 0.017 (± 0.005) | < 0.005 |

| Muscle* | < 0.005 | < 0.005 |

| Spleen | < 0.005 | < 0.005 |

| Femur | < 0.005 | < 0.005 |

Muscle and fibrous tissue surrounding the implant.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the National Institutes of Health (R01 AR45871 and R01 EB03060) and The Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development ZonMW (Agiko 920-03-325) and Stichting Anna Fonds for financial support. The authors thank Dr. Shanfeng Wang and Mr. James Greutzmacher from the Tissue Engineering and Biomaterials laboratory and Mr. Rodney Landsworth and Mr. Al Amundson from Radiation Safety at Mayo Clinic for their contributions to this work.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Hori K, Sotozono C, Hamuro J, Yamasaki K, Kimura Y, Ozeki M, Tabata Y, Kinoshita S. Controlled-release of epidermal growth factor from cationized gelatin hydrogel enhances corneal epithelial wound healing. J Control Release. 2006 doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2006.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ruhe PQ, Boerman OC, Russel FG, Mikos AG, Spauwen PH, Jansen JA. In vivo release of rhBMP-2 loaded porous calcium phosphate cement pretreated with albumin. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2006;17(10):919–927. doi: 10.1007/s10856-006-0181-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Woo BH, Fink BF, Page R, Schrier JA, Jo YW, Jiang G, DeLuca M, Vasconez HC, DeLuca PP. Enhancement of bone growth by sustained delivery of recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 in a polymeric matrix. Pharm Res. 2001;18(12):1747–1753. doi: 10.1023/a:1013382832091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li RH, Bouxsein ML, Blake CA, D'Augusta D, Kim H, Li XJ, Wozney JM, Seeherman HJ. rhBMP-2 injected in a calcium phosphate paste (alpha-BSM) accelerates healing in the rabbit ulnar osteotomy model. J Orthop Res. 2003;21(6):997–1004. doi: 10.1016/S0736-0266(03)00082-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abdiu A, Walz TM, Wasteson A. Uptake of 125I-PDGF-AB to the blood after extravascular administration in mice. Life Sci. 1998;62(21):1911–1918. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(98)00159-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gao T, Uludag H. Effect of molecular weight of thermoreversible polymer on in vivo retention of rhBMP-2. J Biomed Mater Res. 2001;57(1):92–100. doi: 10.1002/1097-4636(200110)57:1<92::aid-jbm1146>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hosseinkhani H, Hosseinkhani M, Khademhosseini A, Kobayashi H. Bone regeneration through controlled release of bone morphogenetic protein-2 from 3-D tissue engineered nano-scaffold. J Control Release. 2007;117(3):380–386. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2006.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Uludag H, Gao T, Wohl GR, Kantoci D, Zernicke RF. Bone affinity of a bisphosphonate-conjugated protein in vivo. Biotechnol Prog. 2000;16(6):1115–1118. doi: 10.1021/bp000066y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Friess W, Uludag H, Foskett S, Biron R, Sargeant C. Characterization of absorbable collagen sponges as rhBMP-2 carriers. Int J Pharm. 1999;187(1):91–99. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5173(99)00174-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Uludag H, D'Augusta D, Golden J, Li J, Timony G, Riedel R, Wozney JM. Implantation of recombinant human bone morphogenetic proteins with biomaterial carriers: A correlation between protein pharmacokinetics and osteoinduction in the rat ectopic model. J Biomed Mater Res. 2000;50(2):227–238. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(200005)50:2<227::aid-jbm18>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Uludag H, Friess W, Williams D, Porter T, Timony G, D'Augusta D, Blake C, Palmer R, Biron B, Wozney J. rhBMP-collagen sponges as osteoinductive devices: effects of in vitro sponge characteristics and protein pI on in vivo rhBMP pharmacokinetics. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999;875:369–378. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb08519.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Uludag H, Gao T, Porter TJ, Friess W, Wozney JM. Delivery systems for BMPs: factors contributing to protein retention at an application site. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83-A(Pt 2) Suppl 1:S128–S135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Takahashi Y, Yamamoto M, Tabata Y. Enhanced osteoinduction by controlled release of bone morphogenetic protein-2 from biodegradable sponge composed of gelatin and beta-tricalcium phosphate. Biomaterials. 2005;26(23):4856–4865. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Uludag H, D'Augusta D, Palmer R, Timony G, Wozney J. Characterization of rhBMP-2 pharmacokinetics implanted with biomaterial carriers in the rat ectopic model. J Biomed Mater Res. 1999;46(2):193–202. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(199908)46:2<193::aid-jbm8>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yamamoto M, Tabata Y, Hong L, Miyamoto S, Hashimoto N, Ikada Y. Bone regeneration by transforming growth factor beta1 released from a biodegradable hydrogel. J Control Release. 2000;64(1–3):133–142. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(99)00129-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yamamoto M, Takahashi Y, Tabata Y. Controlled release by biodegradable hydrogels enhances the ectopic bone formation of bone morphogenetic protein. Biomaterials. 2003;24(24):4375–4383. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(03)00337-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Delgado JJ, Evora C, Sanchez E, Baro M, Delgado A. Validation of a method for non-invasive in vivo measurement of growth factor release from a local delivery system in bone. J Control Release. 2006;114(2):223–229. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2006.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Louis-Ugbo J, Kim HS, Boden SD, Mayr MT, Li RC, Seeherman H, D'Augusta D, Blake C, Jiao A, Peckham S. Retention of 125I-labeled recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 by biphasic calcium phosphate or a composite sponge in a rabbit posterolateral spine arthrodesis model. J Orthop Res. 2002;20(5):1050–1059. doi: 10.1016/S0736-0266(02)00011-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ruhe PQ, Boerman OC, Russel FG, Spauwen PH, Mikos AG, Jansen JA. Controlled release of rhBMP-2 loaded poly(dl-lactic-co-glycolic acid)/calcium phosphate cement composites in vivo. J Control Release. 2005;106(1–2):162–171. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2005.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seeherman H, Li R, Wozney J. A review of preclinical program development for evaluating injectable carriers for osteogenic factors. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85-A Suppl 3:96–108. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200300003-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yokota S, Uchida T, Kokubo S, Aoyama K, Fukushima S, Nozaki K, Takahashi T, Fujimoto R, Sonohara R, Yoshida M, Higuchi S, Yokohama S, Sonobe T. Release of recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein 2 from a newly developed carrier. Int J Pharm. 2003;251(1–2):57–66. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5173(02)00581-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kempen DHR, Lu L, Hefferan TE, Creemers LB, Maran A, Classic KL, Dhert WJA, Yaszemski MJ. Retention of in vitro and in vivo BMP-2 bioactivity in sustained delivery vehicles for bone tissue engineering. Accepted by Biomaterials. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.04.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boyan BD, Lohmann CH, Somers A, Niederauer GG, Wozney JM, Dean DD, Carnes DL, Jr, Schwartz Z. Potential of porous poly-D,L-lactide-co-glycolide particles as a carrier for recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 during osteoinduction in vivo. J Biomed Mater Res. 1999;46(1):51–59. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(199907)46:1<51::aid-jbm6>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Duggirala SS, Mehta RC, DeLuca PP. Interaction of recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 with poly(d,l lactide-co-glycolide) microspheres. Pharm Dev Technol. 1996;1(1):11–19. doi: 10.3109/10837459609031413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kempen DH, Lu L, Kim C, Zhu X, Dhert WJ, Currier BL, Yaszemski MJ. Controlled drug release from a novel injectable biodegradable microsphere/scaffold composite based on poly(propylene fumarate) J Biomed Mater Res A. 2006;77(1):103–111. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kempen DHR, Kim CW, Lu L, Dhert WJA, Currier BL, Yaszemski MJ. Controlled release from poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) microspheres embedded in an injectable, biodegradable scaffold for bone tissue engineering. Materials Science Forum. 2003;(426–432):3151–3156. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oldham JB, Lu L, Zhu X, Porter BD, Hefferan TE, Larson DR, Currier BL, Mikos AG, Yaszemski MJ. Biological activity of rhBMP-2 released from PLGA microspheres. J Biomech Eng. 2000;122(3):289–292. doi: 10.1115/1.429662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rai B, Teoh SH, Hutmacher DW, Cao T, Ho KH. Novel PCL-based honeycomb scaffolds as drug delivery systems for rhBMP-2. Biomaterials. 2005;26(17):3739–3748. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.09.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schrier JA, DeLuca PP. Recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 binding and incorporation in PLGA microsphere delivery systems. Pharm Dev Technol. 1999;4(4):611–621. doi: 10.1081/pdt-100101400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yamamoto M, Ikada Y, Tabata Y. Controlled release of growth factors based on biodegradation of gelatin hydrogel. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed. 2001;12(1):77–88. doi: 10.1163/156856201744461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang S, Lu L, Yaszemski MJ. Bone-tissue-engineering material poly(propylene fumarate): correlation between molecular weight, chain dimensions, and physical properties. Biomacromolecules. 2006;7(6):1976–1982. doi: 10.1021/bm060096a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ranger NT. Radiation detectors in nuclear medicine. Radiographics. 1999;19(2):481–502. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.19.2.g99mr30481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]