Abstract

Background

Bisphosphonates are medications that impact bone reformation by inhibiting osteoclast function. Osteonecrosis of the jaw has been reported among patients receiving these medications. It is unclear if the risk factors associated with osteonecrosis of the jaw among cancer patients taking bisphosphonates are also possible risk factors among patients receiving these medications for other indications.

Methods

A systematic review search strategy was used to identify cases of osteonecrosis of the jaw among patients taking bisphosphonates for an indication other than cancer to identify potential contributing factors. Data were analyzed according to previous models to develop a more expanded model that may explain possible mechanisms for the development of osteonecrosis of the jaw among patients without cancer.

Results

Ninety-nine cases of osteonecrosis of the jaw were identified among patients who were prescribed a bisphosphonate for an indication other than cancer. These cases included 85 osteoporosis patients, 10 patients with Paget’s disease, two patients with rheumatoid arthritis, one patient with diabetes and one patient with maxillary fibrous dysplasia. The mean age was 69.4 years, 87.3% were female, and 87.6% were receiving oral, but not intravenous, bisphosphonates. Of the 63 patients reporting dental care information, 88.9% had a dental procedure prior to the onset of osteonecrosis of the jaw. Of all cases providing medical information, 71% were taking at least one medication that affects bone turnover in addition to the bisphosphonate, and 81.6% reported additional underlying health conditions.

Conclusions

The case details suggest a multiplicity of factors associated with this condition and provide the foundation for a model outlining the potential mechanism for the development of osteonecrosis of the jaw among patients taking bisphosphonates for an indication other than cancer.

Keywords: bisphosphonates, osteonecrosis of the jaw, osteoporosis, Paget’s diesase

Introduction

Bisphosphonates impact bone reformation by the inhibition of osteoclast function and are currently used to treat hypercalcemia of malignancy, bone metastases, Paget’s disease, and osteoporosis. However, widespread use of bisphosphonates has been curbed by reports of osteonecrosis of the jaw among both cancer and osteoporotic patients receiving these medications. Although direct causation has not been established, the associated risk has been deemed sufficient for the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and drug manufacturers to include risk of osteonecrosis of the jaw in bisphosphonate package insert materials.

Osteonecrosis of the hip, knee, jaw or other bones affects approximately 20,000 people per year.1,2 Osteonecrosis of the jaw has been reported as a rare complication of bone disorders and phosphorus exposure since the 1830s;3 however, many incident cases may have been underreported over the years until it was noticed that osteonecrosis of the jaw was occurring among some patients receiving bisphosphonates.4

Hundreds of cases of osteonecrosis of the jaw have been reported to national adverse event reporting systems. Approximately 94% of reported cases among bisphosphonate users have occurred among cancer patients who receive the more potent intravenous bisphosphonate formulations.5 Incidence estimates of osteonecrosis of the jaw vary considerably, from 1 in 1,260 to less than 1 in 100,000 osteoporosis patients.6, 7 Among those undergoing dental procedures, incidence may range from 1 in 296 to 1 in 1,130.6, 7 Recent prevalence studies show that approximately 10–50% of cases of osteonecrosis of the jaw occur among bisphosphonate users, while 50–90% of cases occurred in the absence of these medications.8, 9

Equivalent rates of osteonecrosis of the jaw were shown among the bisphosphonate-treated as compared to the control population in a randomized zoledronate trial of 3,889 osteoporosis patients.10 The potential preventive effects of bisphosphonates are important; therefore, we have the responsibility to fully understand the attribution of side effects such as osteonecrosis of the jaw so that the risk to benefit ratio can be accurately represented to patients without cancer as well as to cancer patients. This knowledge will help to identify appropriate candidates for preventive care who stand to receive the most benefit with the least risk based on the presence or absence of risk factors for osteonecrosis of the jaw.

Although osteonecrosis of the jaw is known to occur to some in both patients who have received bisphosphonates as well as those who have never been exposed to these medications,10, 11 it is unclear which patients may be at greatest risk. Recent oral surgery, tooth extraction, denture use, and poor oral hygiene are factors that have been implicated in osteonecrosis of the jaw among patients taking bisphosphonates.12–14 Other risk factors for osteonecrosis of the jaw have been proposed and may include diabetes, co-morbid conditions, and steroid use.15, 16

Osteonecrosis in general has been associated with a wide variety of factors including advanced age, arthritis, chronic inactivity, corticosteroids, estrogen, female sex, hemodialysis, thrombophilic disorders, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, infection, and many other disorders.13,17,18 Published models of the possible contributing factors for osteonecrosis of the jaw have focused on issues related to bisphosphonate use in cancer populations, but may be useful to guide the exploration of potential contributing factors in patients taking bisphosphonates for indications other than cancer as well.13, 19

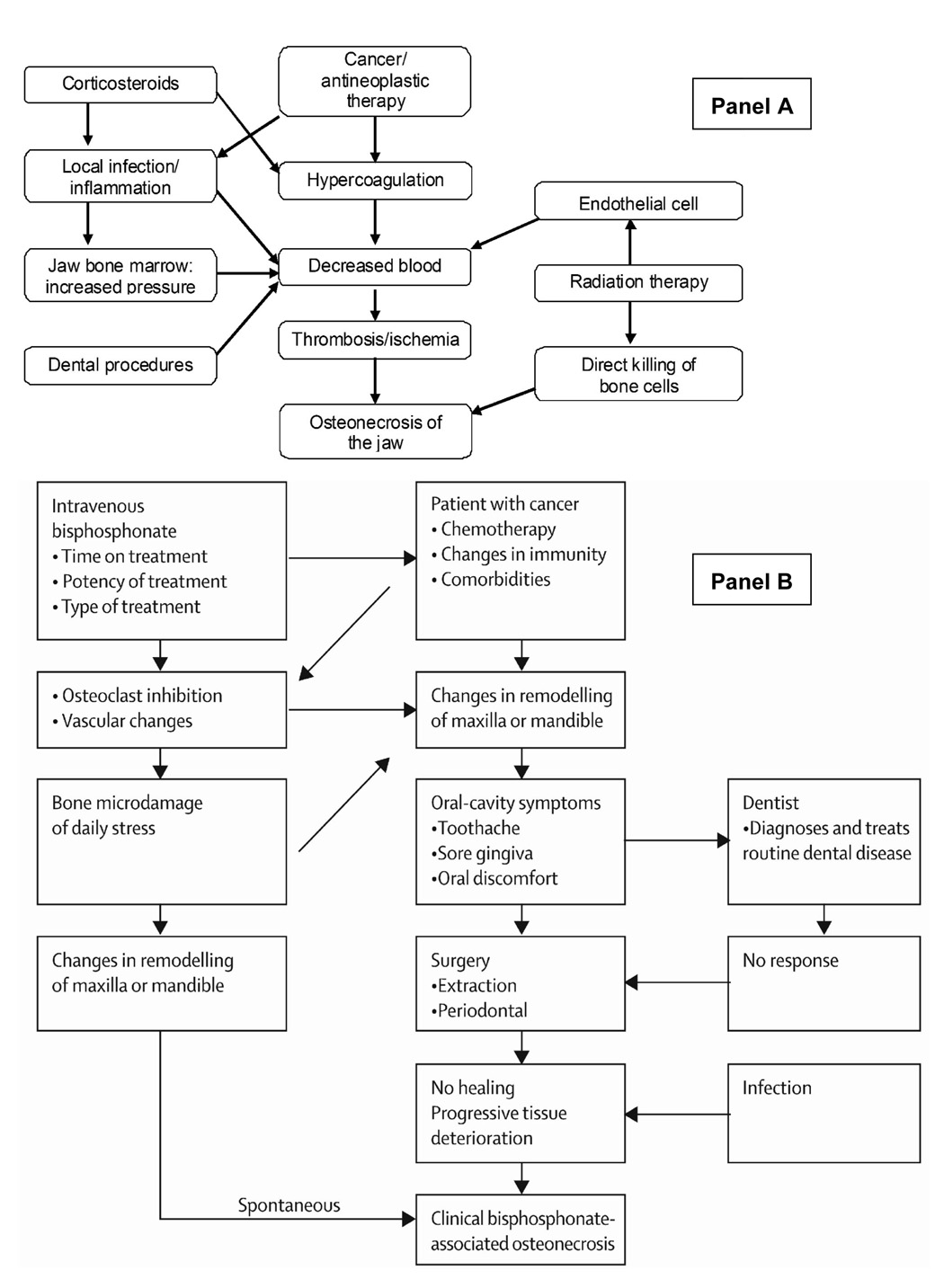

This study was designed to identify cases of osteonecrosis of the jaw in patients taking bisphosphonates for an indication other than cancer to identify potential contributing factors that may be unique to this population. Data were collected using a systematic review strategy to obtain information related to previous models of osteonecrosis of the jaw among cancer patients (Figure 1) and prior suggested risk factors.13, 17, 18 The goal was to develop a model that may explain possible mechanisms for the development of osteonecrosis of the jaw in patients with no history of cancer who receive bisphosphonates.

Figure 1.

Models of the development of development of osteonecrosis of the jaw among cancer patients treated with bisphosphonates. Reprinted with permission. Panel A13; Panel B19

Methods

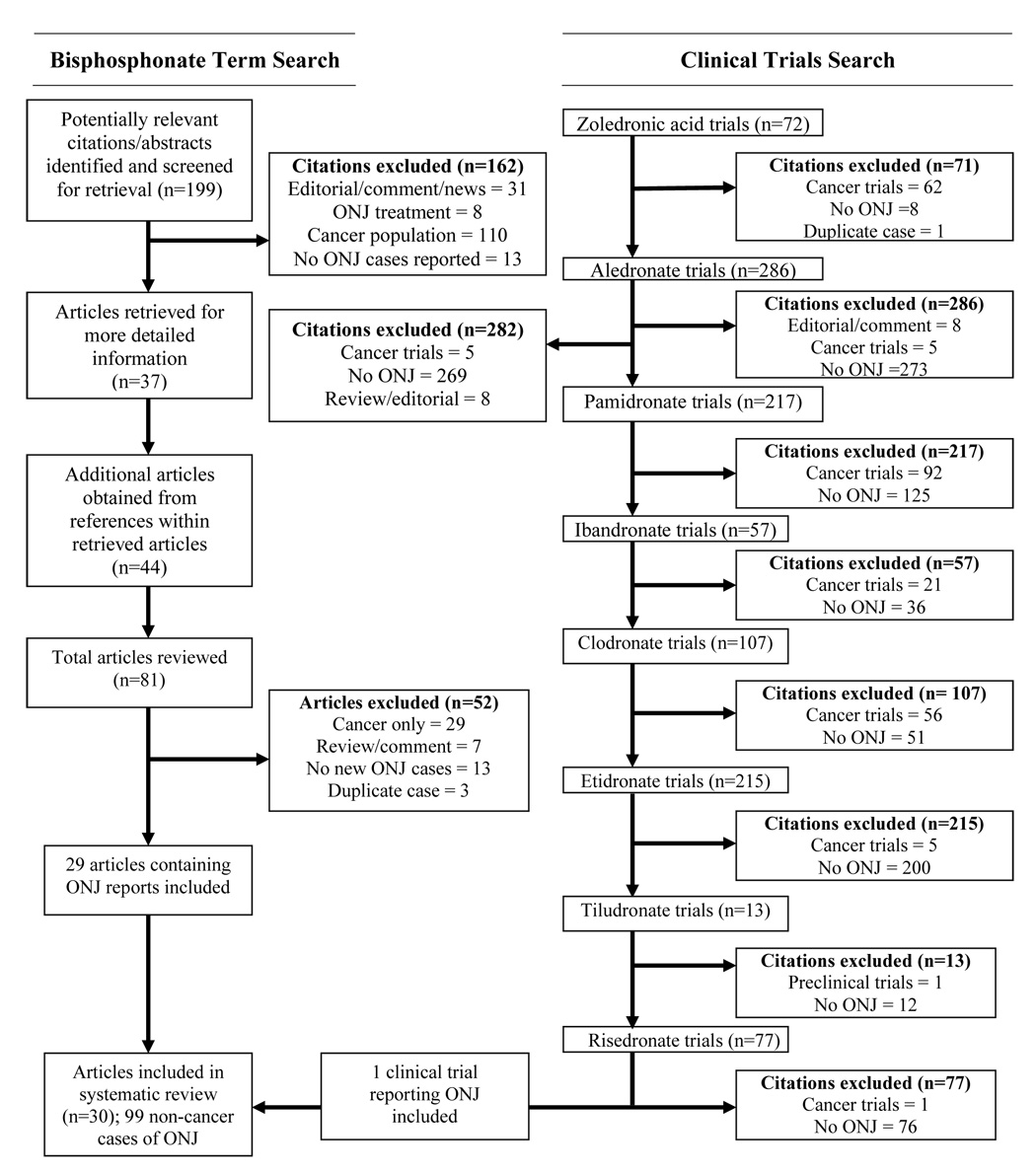

A systemic review was conducted to identify cases of osteonecrosis of the jaw among individuals receiving bisphosphonates for an indication other than cancer. The search included articles published from January 1996 through October 2007. Prior reviews16, 20–22 were used to identify cases that may have been published prior to 1996. The MedLine search strategy included any of the following terms: bisphosphonate, risedronate, ibandronate, alendronate, pamidronate, etidronate, etidronic acid, clodronate, clodronic acid, tiludronate, zoledronate, or zoledronic acid. These terms then were combined with the expanded terms osteonecrosis or jaw. A second MedLine search was performed in which each bisphosphonate term was utilized with a category term for clinical trials. Each clinical trial was reviewed to assess the reported adverse events for indications of osteonecrosis of the jaw among study participants without cancer.

Articles were excluded if they were letters, case reports or reviews exclusively related to a cancer population, the abstract specifically stated there were no cases of osteonecrosis of the jaw, the article focused only on treatment or diagnosis, or if the article did not reference specific cases of osteonecrosis of the jaw. Articles published in languages other than English were translated by MultiLingual Solutions, Inc. (Rockville, MD). Citations from the obtained articles were also reviewed. Data regarding patient age, gender, diagnoses, concomitant medications, dose and duration of bisphosphonate use, and dental procedures were abstracted. To be eligible, a published case must have explicitly stated the diagnosis of osteonecrosis in the jaw. All citations were reviewed to identify potential case duplication. Authors of published articles were contacted to attempt to obtain unpublished clinical information to obtain complete data for this study. Potential factors for the development of the proposed model of risk factors were restricted to those characteristics in at least 40% of cases.

Results

The initial MedLine search strategy resulted in 6,132 articles that included a bisphosphonate term. This number was reduced to 199 when the expanded terms osteonecrosis and jaw were required. The article abstracts were reviewed, and 37 articles were obtained for review. An additional 42 articles were identified within the citations of articles reviewed. Several of the full case reports23–25 were preceded by brief commentaries,26–28 thus only the more recent report of those cases was included to avoid duplication. Cases that were reported in more than one publication were limited to the more recent or most detailed publication. The clinical trials search resulted in 72 zoledronate, 286 alendronate, 217 pamidronate, 57 ibandronate, 107 clodronate, 13 tiludronate, 215 etidronate, and 77 risedronate clinical trials. The results of the review process are presented in Figure 1. Of the included articles, one in Hebrew,29 one in French,30 and one article in German31 were translated to English. The 30 articles identified in this systematic review discussed 99 cases of osteonecrosis of the jaw among patients without cancer who had been treated with bisphosphonates (85 osteoporosis patients, 10 patients with Paget’s disease, and four patients with other diseases). The mean age was 69.4 years, 87.3% were female, and 87.6% were receiving oral, but not intravenous, bisphosphonates. Of the 63 patients reporting dental care information, 88.9% had a dental procedure prior to the onset of osteonecrosis of the jaw. Of the cases reporting concomitant medication use, 71% were taking at least one medication that affects bone turnover in addition to the bisphosphonate, and 80.6% had additional underlying medical conditions. A summary of the identified articles is presented in Table 1, and a summary of individual cases in Table 2

Table 1.

List of publications identified

| Publication | Cases Reported | Concomitant medications provided | Dental work information provided |

|---|---|---|---|

| Black et al.10 | Osteoporosis = 1 | NO | YES |

| Brooks et al.48 | Osteoporosis=1 Osteopenia=1 |

YES | YES |

| Carter et al.23 | Paget’s Disease = 3 | YES | YES |

| Cheng et al.32 | Osteoporosis = 3 Paget’s Disease = 2 |

YES | YES |

| Clarke et al.45 | Osteoporosis = 1 | YES | YES |

| Danneman et al.44 | Osteoporosis = 3 | NO | YES |

| Dimitrakopoulos et al.56 | Fibrous Dysplasia = 1 | NO | YES |

| Farrugia et al.46 | Osteoporosis = 4 Paget’s disease = 1 |

NO | YES |

| Friedrich and Blake57 | Diabetes = 1 | YES | YES |

| Heras-Rincón et al.49 | Osteoporosis = 2 | NO | YES |

| Hoefert and Eufinger31 | Osteoporosis = 1 | YES | YES |

| Kademani et al.12 | Osteoporosis = 1 | YES | NO |

| Khamaisi et al.15 | Osteoporosis = 1 Rheumatoid arthritis = 1 |

NO | NO |

| Levin et al.54 | Osteoporosis = 1 | YES | YES |

| Malden and Pai50 | Osteoporosis = 1 Rheumatoid arthritis = 1 |

YES | YES |

| Marunick et al.40 | Osteoporosis = 1 | YES | YES |

| Marx et al.39 | Osteoporosis = 4c | NO | NO |

| Mavrokokki et al.6 | Osteoporosis = 24a Paget’s disease = 4b |

NO | NO |

| Merigo et al.43 | Osteoporosis = 3 | NO | YES |

| Migliorati et al.25 | Osteopenia = 1 | YES | YES |

| Milillo et al.55 | Osteoporosis = 9 | NO | YES |

| Najm et al.30 | Osteoporosis = 3 | NO | YES |

| Nase and Suzuki52 | Osteoporosis = 1 | Partial | YES |

| Oltolina et al.42 | Microfractures = 1 | YES | YES |

| Phal et al.51 | Osteoporosis = 4 | NO | YES |

| Pozzi et al.53 | Osteoporosis = 1 | NO | NO |

| Purcell and Boyd38 | Osteoporosis = 1 | NO | YES |

| Ruggiero et al.37 | Osteoporosis = 7 | NO | NO |

| Shlomi et al.29 | Osteoporosis = 3 | YES | YES |

| Wang et al.47 | Osteoporosis = 1 | YES | YES |

| Yeo et al.41 | Osteoporosis = 1 | YES | YES |

3 additional cases were previously reported in Cheng et al.32, and are removed from this analysis to avoid duplication

2 additional cases were previously reported in Cheng et al. 32, and are removed from this analysis to avoid duplication

Three osteoporosis cases were previously reported by Marx et al.24

Table 2.

Cases identified

| Case | Year reported | Age | Gender | Other conditions | Dental, procedure | Other medications | Bisphosphonate used | Dose | Duration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OSTEOPOROSIS | |||||||||

| 1 | 200437 | 77 | F | NS | NS | NS | Oral Alendronate | NS | NS |

| 2 | 200437 | 82 | F | NS | NS | NS | Oral Alendronate | NS | NS |

| 3 | 200437 | 80 | F | NS | NS | NS | Oral Risedronate | NS | NS |

| 4 | 200437 | 72 | M | NS | NS | NS | Oral Alendronate + IV Zoledronate | NS | NS |

| 5 | 200437 | 59 | F | NS | NS | NS | Oral Alendronate | NS | NS |

| 6 | 200437 | 60 | F | NS | NS | NS | Oral Alendronate | NS | NS |

| 7 | 200437 | 68 | F | NS | NS | NS | Oral Alendronate | NS | NS |

| 8 | 200538 | 67 | F | NS | NS | Prednisonolone, leflunomidef, celecoxib | Oral Alendronate | NS | NS |

| 9 | 200739 | 70 | F | Controlled hypertension | None | NSc | Oral Alendronate | 70 mg/wk | 5 years |

| 10 | 200739 | 58 | F | Osteopenia | Six dental implants (occluding against a fixed prothesis) | NS, steroid for 5 days during infection | Oral Alendronate | 70 mg/wk | 5 years |

| 11 | 200739 | 58 | F | None | Dental implant | NSc | Oral Alendronate | 10 mg/day, followed by 70 mg/week | 1 year followed by 3 years |

| 12 | 200739 | 60 | F | NS | Root canal, extraction | Atenolol, hydro-chlorothiazide | Oral alendronate | 10 mg/day followed by 70 mg/week | 3 years followed by 7 years |

| 13 | 200525 | 61 | F | NS | Oral surgerya | Losartan, amlodipine, furosemide, esomeprazole, aspirin, potassium | Oral Alendronate | NS | 3 years |

| 14 | 200540 | 59 | F | Rheumatoid arthritis | Tooth extraction | Prednisone, methotrexate a | Oral Alendronate | 70 mg/wk a | ~ 3 years a |

| 15 | 200541 | 58 | F | Lupus erythematosus | Tooth extraction | Prednisolone, glucosamine sulfate | Oral Alendronate | weekly | NS |

| 16b | 200532 | 72 | M | NS | Tooth extraction | None | Oral Alendronate | 40 mg/wk | 3 years |

| 17b | 200532 | 60g | M | NS | Tooth extraction | None | Oral Alendronate | 40 mg/wk | 1 year |

| 18b | 200532 | 58 | F | NS | Deep bony impacted wisdom tooth removal | Bactrim, neurontin, amitriptyline | Oral Alendronate | 40 mg/wk | Started alendronate after tooth removal |

| 19 | 200542 | 64 | M | Cardiac graft, micro-fractures of the spinal column | Tooth extraction | Cyclosporine, high-dose steroids | IV Pamidronate | 90 mg/4 wk a | 18 months a |

| 20 | 200530 | 45 | M | NS | None | Cortisone | IV Pamidronate + IV Zoledronate | P: 30mg/3mo + Z: 4mg/mo | 79 months |

| 21 | 200530 | 83 | F | NS | Removal of dental implant | Oral Alendronate | 70 mg/wk | 44 months | |

| 22 | 200530 | 84 | F | NS | Tooth extraction | Cortisone | Oral Alendronate | 70 mg/wk | 25 months |

| 23 | 200529 | 73 | F | Rheumatoid arthritisa | Tooth extractiona | Prednisonea | Oral Alendronate | NS | 5 years |

| 24 | 200529 | 48 | F | Diabetesa | Tooth extractiona | Oral hypoglycemic agenta | Oral Alendronate | NS | 2 years |

| 25 | 200529 | 72 | F | Diabetesa | Tooth extractiona | Insulin, dailya | Oral Alendronate | NS | 5 years |

| 26 | 200531 | 65 | F | Hypertonic diseasea | Oral surgerya | Premarin, aspirin, enalapril, fluvastatin a | Oral Alendronate | 70 mg/wk | 2 years |

| 27 | 200612 | 64 | F | NS | Tooth extraction | Antibiotics | IV Pamidronate | NS | NS |

| 28 | 200643 | 70 | F | NS | Tooth extraction | NSc | Oral Alendronate | 70 mg/wk | 3 years |

| 29 | 200643 | 61 | F | NS | Tooth extraction | NSc | Oral alendronate | 70 mg/wk | 2.5 years |

| 30 | 200643 | 78 | F | NS | Tooth extraction | NSc | Oral Alendronate | 70 mg/wk | ~5 years |

| 31 | 200744 | NS | F | NS | Tooth extraction | NS | Oral Alendronate | NS | >5 years |

| 32 | 200744 | NS | F | NS | Tooth extraction | NS | Oral Alendronate | NS | >5 years |

| 33 | 200744 | NS | F | NS | Tooth extraction | NS | Oral Alendronate | NS | >5 years |

| 34 | 200715 | 71 | F | Impaired fasting glucose | Dental Surgery a | NS | Oral Alendronate | 70 mg/wk | >6 months a |

| 35 | 200745 | 75 | F | Hypertension; hyperlipidemia; history of fibromuscular dysplasia, cerebral aneurysma | Recent dental work | Hydrochlorothiazide + losartan, simvastatin, nifedipine, omeprazole a | Oral Alendronate | NS | 1 year |

| 36 | 200646 | 83 | F | NSd | Tooth extraction | NSd | Oral Alendronate | NS | NS |

| 37 | 200646 | 77 | F | NSd | Tooth extraction | NSd | Oral Alendronate | NS | NS |

| 38 | 200646 | 63 | F | NSd | Tooth extraction | NSd | Oral Alendronate | NS | NS |

| 39 | 200646 | 78 | F | NSd | Tooth extractions | NSd | Oral Alendronate | NS | NS |

| 40 | 200710 | NS | F | NS | Oral surgery | NS | IV Zoledronic acid | 5 mg/year | NS |

| 41 | 200747 | 65 | F | Arthritis, periodontitis, endentulism with functional deficit | Tooth extraction, dental implant | Calcium; teriparatide (at discontinuation of aledronate following dental implant); postsurgical azithromycin, hydrocodone, acetaminophen, ibuprofen, cephalexin | Oral Aledronate | Daily | 10 years |

| 42 | 200748 | 70 | F | Advanced periodontitis; chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | Extraction | Prednisone; sertaline; clonidine; hydrochlorothiazide; fexofenadine; ipratropium and albuterol inhaler; tiotropium inhaler; fluticasone and salmeterol inhaler; potassium; supplemental oxygen | Oral risedronate | 35 mg/week | ~2 years |

| 43 | 200748 | 62 | F | Advanced periodontis | Dental implant | NS | Oral risedronate | 35 mg/week | 1 year |

| 44 | 200749 | 75 | F | NS | Tooth extraction a | NS | Oral alendronate | NS | NS |

| 45 | 200749 | 73 | F | NS | Tooth extraction a | NS | Oral alendronate | NS | NS |

| 46 | 200750 | 64 | F | Periodontal disease with regular tooth extractions | Tooth extraction | NS | Risedronate | NS | NS |

| 47 | 200751 | 82 | F | NS | Tooth extraction | NS | Oral alendronate | NS | NS |

| 48 | 200751 | 70 | F | NS | Tooth extraction | NS | Oral alendronate | NS | NS |

| 49 | 200751 | 85 | F | NS | Tooth extraction | NS | Oral alendronate | NS | NS |

| 50 | 200751 | 74 | F | NS | None | NS | Oral alendronate | NS | NS |

| 51 | 200652 | 78 | F | Renal insufficiency, diverticulosis, clinical depression, poor oral self-care, gingivitis, xerostomia | Tooth extraction | Tolterodine, sertraline, atorvastatin, aspirin, calcium salt, cholecalciferol, ginko bilboa | Oral alendronate | 10 mg/day | 5 years |

| 52 | 200553 | NS | F | Myelodysplasia a | Patient edentulous, with prosthesis a | Steroid | NS | NS | NS |

| 53 | 200754 | 66 | F | Hypertension, hypercholester olemia a | No (removable partial denture) | Statin, calcium channel blocker a | Oral alendronate | 10 mg/day followed by 70 mg/week | 6 years followed by 2 years |

| 54–62e | 200755 | NS | NS | NS | Tooth extraction (all pts) | NS | Oral alendronate OR Oral aledronate + clodronate | NS | NS |

| 63–85e | 20076 | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | Oral alendronate (n=19) Risedronate (n=2) Alendronate + Risedronate (n=2) | NS | NS |

| PAGET’S DISEASE | |||||||||

| P1 | 200523 | 73 | M | NS | Tooth extraction | Amlodipine, tramadol, perindopril | Oral Alendronate | 40 mg/day | 5 years |

| P2 | 200523 | 78 | F | NS | None | None | IV Pamidronate | 90 mg/mo | 18 months |

| P3 | 200523 | 84 | F | NS | Tooth extraction | Diltiazem, simvastatin, ferrous sulfate, aspirin, bendrofluazine | IV Pamidronate | 60 mg/mo | 6 months |

| P4b | 200532 | 69 | M | NS | Tooth extraction | Metformin, atenolol, simvastatin, morphine, calcitonin, amitriptyline | Oral Alendronate | 40 mg/wk | 6 months |

| P5 | 200532 | 82 | F | NS | Tooth extraction | Thyroxine, NSAIDs | IV Pamidronate + Oral Alendronate | P: 90 mg (1 dose) + A: 20mg/day | P: 5 years A: 1 year |

| P6 | 200646 | 79 | M | NSd | None | NSd | Oral alendronate | NS | NS |

| P7–10e | 20076 | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | Oral alendronate (n=2) Pamidronate (n=2) | NS | NS |

| OTHER | |||||||||

| OT1 | 200656 | 59 | F | Maxillary fibrous dysplasia a | None | None a | IV zoledronic acid | NS | 6 months |

| OT2 | 200715 | 73 | F | Rheumatoid arthritis, impaired fasting glucose | Dental surgery a | NS | Oral alendronate | 70 mg/wk | >6 months a |

| OT3 | 200757 | 75 | F | Diabetes, sarcoidosis | Tooth extraction | Prednisone, insulin | IV zoledronic acid | NS | 3 years |

| OT4 | 200750 | 56 | F | Rheumatoid arthritis | Tooth extraction | Leflunomide, prednisone, diclofenac, iron, omeprazole | Oral alendronate | NS | NS |

NS = not stated

Personal communication with author

Incorrect dose/drug prescribing error noted in TGA report associated with this case58

Patient was not taking corticosteroids

Although details of medications/illnesses were not provided, publication states there were none that could have contributed to the ONJ

Summary data only, no individual case details provided

Contraindicated in patients over age 65 due to increased risk of infection

Per author, the original publication incorrectly noted this patient’s age as 39. The correct age of this patient was 60.

Osteoporosis

Eighty-five osteoporotic patients using bisphosphonates were identified who had been diagnosed with osteonecrosis of the jaw. The mean age was 68.7 years (standard deviation 9.4) and 90.6% were female. The majority of these patients (96.5%) were receiving oral bisphosphonates. Sixty-three (74.1%) were taking oral alendronate, six (7.1%) were taking oral risedronate, two (2.4%) were receiving intravenous pamidronate, and four patients were receiving dual bisphosphonate therapy: oral alendronate plus intravenous zoledronate (n=1, 1.2%); aledronate plus risedronate (n=2, 2.4%); and pamidronate plus zoledronate (n=1, 1.2%). An additional ten patients (11.8%) did not provide individual-level data, but included nine patients who were taking oral alendronate alone or alendronate plus clodronate.

Of the 53 (62.4%) cases with dental information, 49 (92.5%) had a dental procedure prior to the onset of osteonecrosis of the jaw. Twenty-four cases (28.2%) provided information on concomitant medication use. Of these, 17 (70.8%) were taking between one and five medications, in addition to a bisphosphonate, that are known to affect bone turnover (Table 3). The most common medications included steroids (n=10, 41.7%), diuretics (n=4, 16.7%), statins (n=4, 16.7%) and calcium channel blockers (n=3, 12.5%). Three of the osteoporosis cases had associated Therapeutic Goods Association adverse event reports that indicated incorrect dosing or a drug prescribing error had occurred with the bisphosphonate prescribed. Among cases providing clinical information, 26.3% reported poor oral health or other underlying oral conditions (e.g. periodontis, gingivitis), 21.1% had rheumatoid arthritis or lupus, and 15.8% had diabetes or impaired glucose function.

Table 3.

Summary of potential contributing factors among patients with ONJ while taking bisphosphonates

| Potential Contributing Factor | Osteoporosis | Paget’s disease | Other | TOTAL |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 68.7 (9.4) | 77.5 (5.6) | 65.7 (9.6) | 69.4 (9.4) |

| Dental procedures | 92.5% | 67% | 75% | 88.9% |

| Medications affecting bone turnover, in addition to bisphosphonate use | 69.6% | 80% | 67% | 71% |

| Duration of bisphosphonate use | ||||

| < 6 months | 3.3% | 0% | 0% | 2.6% |

| 6 months - <1 year | 3.3% | 40% | 66.7% | 13.2% |

| 1- <5 years | 53.3% | 20% | 33.3% | 47.4% |

| ≥ 5 years | 40% | 40% | 0% | 36.8% |

| Underlying medical conditions | 90.0% | 50% | 100% | 80.6% |

| Rheumatoid arthritis/lupus | 21.1% | 0% | 50% | 19.4% |

| Diabetes/impaired glucose* | 15.8% | 10% | 50% | 19.4% |

| Periodontal disease/other oral | 26.3% | 0% | 25% | 19.4% |

| Hypertension/hyperlipidemia/hypercholesterolemia* | 21.1% | 75% | 0% | 22.6% |

| Other cardiac | 10.5% | 0% | 0% | 6.5% |

explicitly stated or implied by medication use

Paget’s Disease

Ten patients with Paget’s disease who experienced osteonecrosis of the jaw while receiving bisphosphonates were identified. The mean age of Paget’s disease patients with osteonecrosis of the jaw was 77.5 years (standard deviation 5.6). Of cases reporting gender, 50% were male and 50% were female. Four patients (40.0%) were taking oral alendronate, four patients were taking pamidronate (40.0%), and two patients were taking combination therapy: alendronate plus risedronate (n=1, 10.0%); and alendronate plus pamidronate (n=1, 10.0%). Four out of six patients (67%) had a dental procedure prior to the onset of osteonecrosis of the jaw. Five out of 10 cases (50%) included concomitant medication use, four of these cases (80%) reported use of between one and three concomitant drugs that affect bone turnover (Table 3). One of the Paget’s disease cases32 had an associated Therapeutic Goods Association report that indicated incorrect dosing or a drug prescribing error had occurred with the bisphosphonate prescribed. Of those reporting concomitant medications or medical conditions, 50% (n=4) had additional health issues. These included one patient with diabetes and hypercholesterolemia, two patients with hypertension, one with hypercholesterolemia, and one patient who had problems with thyroid function. Each of these patients also had a dental procedure preceding the onset of osteonecrosis of the jaw. One patient that did not have a prior dental procedure also did not report concomitant medication use; therefore, the relationship of osteonecrosis of the jaw to other factors for this patient could not be explored.

Other conditions

Four additional cases of osteonecrosis of the jaw were identified among women taking bisphosphonates for conditions other than osteoporosis or Paget’s disease. The mean age was 65.8 years (standard deviation 9.6). Two patients were receiving oral alendronate (50%) and two were receiving intravenous zoledronate (50%). Three patients (75%) had a dental procedure prior to the onset of osteonecrosis of the jaw. The patient without a prior dental procedure had a known history of bony disease in her jaw (maxillary fibrous dysplasia). Two cases were identified in patients treated for rheumatoid arthritis, and one case was in a patient with diabetes. All cases (n=2) reporting medication use were taking medications that affect bone turnover (Table 3).

Summary of potential contributing factors

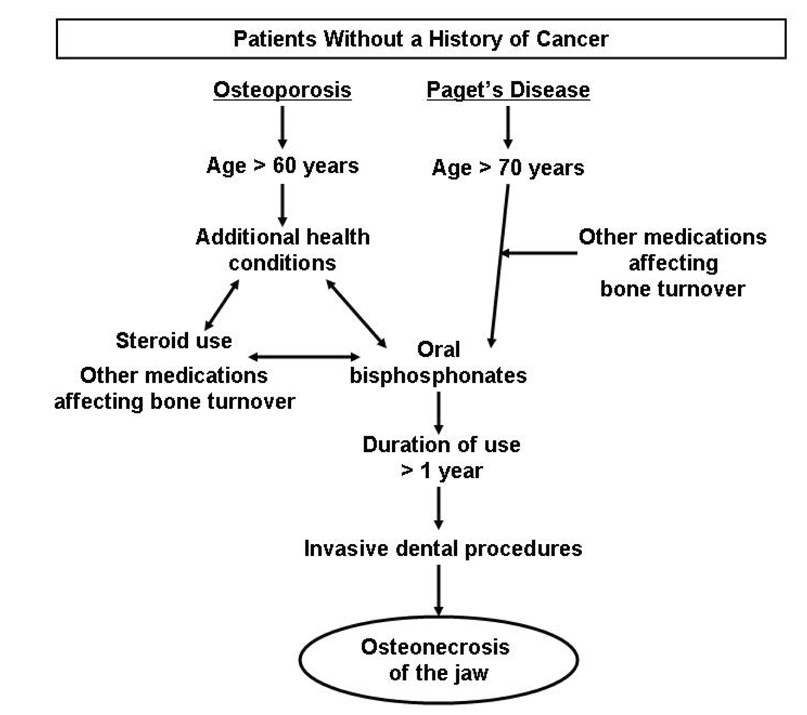

Similar to the cancer population, dental procedures were the most common risk factor, which was associated with 88.9% of all non-cancer cases of osteonecrosis of the jaw among bisphosphonate users.(Table 3) Dental procedures were most common among osteoporosis patients (92.5%) and less common among Paget’s disease patients (67%) prior to onset of osteonecrosis of the jaw. Osteoporosis patients also demonstrated a longer duration of bisphosphonate use (93.3% more than 1 year of use) compared with Paget’s disease (60% more than 1 year of use) or other patients (33.3% more than 1 year of use). The majority of patients also had underlying medical conditions (81.3%) and reported concomitant use of medications that affect bone turnover (70.9%). The most common concomitant medical condition included hypertension, hyperlipidemia or hypercholesterolemia (22.6%). However, patients with osteoporosis were most likely to have periodontal disease or other oral conditions (26.3%), whereas Paget’s disease patients were most likely to have hypertension or hypercholesterolemia (75%), and other patients had a variety of conditions (rheumatoid arthritis, diabetes or other oral conditions). Among those taking medications that affect bone turnover (Table 4), the most commonly used medication affecting bone metabolism included steroids (52.2%). All other medications were used by 20% or less of patients. A model of risk factors, representing reported factors present in more than 40% of the osteoporosis and Paget’s disease patients in this study population, is presented in Figure 3.

Table 4.

Summary of concomitant use of medications that impact bone turnover

| Osteoporosis | Medications |

|---|---|

| Case 8 | Steroids; immunosuppressant |

| Case 10 | Steroids |

| Case 12 | Diuretic; beta-blocker |

| Case 13 | Calcium channel blocker; diuretic; angiotensin receptor blocker; proton pump inhibitor |

| Case 14 | Steroids; methotrexate |

| Case 15 | Steroids |

| Case 19 | Steroids; immunosuppressant |

| Case 20 | Steroids |

| Case 22 | Steroids |

| Case 23 | Steroids |

| Case 26 | ACE inhibitor; statin; hormone replacement therapy |

| Case 35 | Calcium channel blocker; diuretic; angiotensin receptor blocker; proton pump inhibitor; HMG CoA reductase inhibitor |

| Case 41 | Thyroid hormone |

| Case 42 | Diuretic; steroids |

| Case 51 | Statin, calcium salt, cholecalciferol (Vit D) |

| Case 52 | Steroids |

| Case 53 | Statin, calcium channel blocker |

| Paget’s Disease | |

| Case P1 | Calcium channel blocker; ACE inhibitor |

| Case P3 | Calcium channel blocker; statin; diuretic |

| Case P4 | Statin; beta blocker; calcitonin |

| Case P5 | Thyroid hormone |

| Other | |

| Case OT3 | Steroids |

| Case OT4 | Proton pump inhibitor; steroids |

Figure 3.

Proposed model of potential risk factors (> 50% of the study population) associated with osteonecrosis of the jaw among patients with no history of cancer receiving bisphosphonates for osteoporosis or Paget’s disease

Discussion

As a result of this search, 99 cases of osteonecrosis of the jaw among patients receiving bisphosphonates for an indication other than cancer were identified in the published medical literature. The increase in published cases of osteonecrosis of the jaw between 2002 and 2007 is likely related to a combination of patient, disease, and concomitant medication factors, as well as awareness in the medical field,33 as nitrogen-containing bisphosphonates were used for nearly 10 years prior to the first published case of osteonecrosis of the jaw. In this study, there was a predominance of oral bisphosphonate use, as would be expected for patients treated for osteoporosis or Paget’s disease.

There appears to be a consistent association of osteonecrosis of the jaw with invasive dental procedures (e.g. tooth extraction, oral surgery) among patients without cancer, similar to the cancer population. In addition to bisphosphonate use, many of these patients reported taking additional medications that impact bone metabolism, which may have resulted in an additive effect on bone turnover. The concomitant medications may be suggestive of the extent of the underlying disease, which may independently increase risk of osteonecrosis of the jaw (e.g. multiple medications may suggest reduced mobility and subsequent loss of bone mass or may suggest advanced bone disease).

A number of identified cases provide no published or unpublished clinical information about patient health or medication use. There were too little data available to include the other diseases in the risk model. Additionally, cases reported from adverse event reports, which are not comprehensive medical reports, lack patient-level clinical details. However, data from the cases with associated clinical information suggest that those individuals experiencing osteonecrosis of the jaw appear to have multiple contributing factors, primarily co-existing conditions (either implied by the multiple medications or explicitly stated), contraindicated medication use or medication error, and invasive dental procedures prior to the onset of osteonecrosis of the jaw. There were only two published spontaneous case of osteonecrosis of the jaw reported among all osteoporosis patients to date--one in a patient receiving steroid therapy, the other in a patient with controlled hypertension but no steroid use (complete medication information was not reported). Although common among bisphosphonate users diagnosed with osteonecrosis of the jaw, concomitant medication use of additional agents that impact bone turnover appear to be less frequent among osteoporosis patients (69.6%) and other patients (67%) than among those with Paget’s disease (80%), and additional underlying medical conditions were more prevalent among osteoporosis (90.0%) and other patients (100%) than among patients with Paget’s disease (50%). This suggests that there may be differences among these populations and the risk factors may need to be addressed separately depending on the underlying condition for which the bisphosphonate is prescribed.

This model-based systemic review suggests that in the majority of cases, the risk of this morbid condition may not be solely attributable to the bisphosphonate. Osteonecrosis of the jaw does not appear to occur in an otherwise healthy patient taking bisphosphonates; multiple factors are likely associated with this condition. Out of all cases, only one (78 year old patient with Paget’s disease; 90 mg/month intravenous pamidronate for 18 months) reported no underlying medical conditions, concomitant medication use, or dental procedures. These data suggest that osteonecrosis of the jaw may rather be due to a combination of factors that impact the bone of the jaw that, when combined with a bisphosphonate, increase the risk of osteonecrosis of the jaw. Although more than half of those reporting these medications used steroids, it is unclear if the underlying morbid condition and concomitant medication use work together or independently to increase the risk of osteonecrosis of the jaw among bisphosphonate users. There were a variety of underlying medical conditions in this population, including those previously believed to put patients at increased risk of osteonecrosis. In this review, the prevalence of diabetes and hypertention in the published cases of osteonecrosis of the jaw in this review was is similar to the U.S. prevalence estimates,35 36 although the extent of disease is unknown. Therefore, it is unclear if the individual underlying medical conditions in this review truly represent individual risk factors.

In a randomized zoledronate clinical trial,10 one osteoporosis patient receiving placebo and one receiving zoledronic acid experienced osteonecrosis of the jaw, suggesting that incidence may be due in part to the underlying medical condition. Others4,37 have suggested that osteonecrosis of the jaw in the absence of bisphosphonate use has been in existence for some time, but had been underreported, as there is no mechanism of national or international reporting of adverse events in the absence of the concomitant use of an agent monitored by medication safety and regulatory agencies. Of osteonecrosis of the jaw cases identified in two medical record reviews, between 50 and 90% had never received bisphosphonates.8,9 A preliminary FDA review found a total of 100 reports of osteonecrosis/necrosis among users of raloxifene, tamoxifen, estrogen, or calcitonin. This represents a small proportion of the total safety reports (0.18%), but suggests that there may be other cases of osteonecrosis of the jaw unrelated to bisphosphonate use that are not being considered.34

Further work should determine the frequency of osteonecrosis of the jaw among osteoporosis and Paget’s disease patients not taking bisphosphonates. It is important to investigate osteonecrosis of the jaw independent of any particular medication, as it is evident that this condition occurs among users of a variety of other medications and illnesses, and although less commonly, does occur among those with no contraindicated medication use. Future work must address the challenge of separating the drug effects from the underlying effects of the disease it is designed to treat.

Figure 2.

Results of literature search

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by NCI grants P30-CA023074 and R25T-CA078447.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Guerra JJ, Steinberg ME. Distinguishing transient osteoporosis from avascular necrosis of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1995;77(4):616–624. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199504000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roberts A, McMahon R. Causes of Ischemic Bone Damage. [Accessed November 28, 2007];The Maxillofacial Center for Diagnostics & Research. http://wwwmaxillofacialcentercom/NICOcausehtml. (ded)

- 3.Donoghue AM. Bisphosphonates and osteonecrosis: analogy to phossy jaw. Med J Aust. 2005;183(3):163–164. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2005.tb06970.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bouquot JE, McMahon RE. Alveolar osteonecrosis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1997;84(3):229–230. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(97)90334-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shoback D. Update in osteoporosis and metabolic bone disorders. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2007;92(3):747–753. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-0042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mavrokokki T, Cheng A, Stein B, Goss A. Nature and frequency of bisphosphonate-associated osteonecrosis of the jaws in Australia. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;65(3):415–423. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2006.10.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sambrook P, Olver I, Goss A. Bisphosphonates and osteonecrosis of the jaw. Aust Fam Physician. 2006;35(10):801–803. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murad OM, Arora S, Farag AF, Guber HA. Bisphosphonates and osteonecrosis of the jaw: a retrospective study. Endocr Pract. 2007;13(3):232–238. doi: 10.4158/EP.13.3.232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Walter C, Grotz KA, Kunkel M, Al-Nawas B. Prevalence of bisphosphonate associated osteonecrosis of the jaw within the field of osteonecrosis. Support Care Cancer. 2007;15(2):197–202. doi: 10.1007/s00520-006-0120-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Black DM, Delmas PD, Eastell R, et al. Once-yearly zoledronic acid for treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(18):1809–1822. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa067312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lenz JH, Steiner-Krammer B, Schmidt W, Fietkau R, Mueller PC, Gundlach KK. Does avascular necrosis of the jaws in cancer patients only occur following treatment with bisphosphonates? J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2005;33(6):395–403. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2005.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kademani D, Koka S, Lacy MQ, Rajkumar SV. Primary surgical therapy for osteonecrosis of the jaw secondary to bisphosphonate therapy. Mayo Clin Proc. 2006;81(8):1100–1103. doi: 10.4065/81.8.1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ruggiero SL, Gralow J, Marx RE, et al. Practical guidelines for the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of osteonecrosis of the jaw in patients with cancer. J Oncol Pract. 2006;2(1):7–14. doi: 10.1200/jop.2006.2.1.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bilezikian JP. Osteonecrosis of the jaw--do bisphosphonates pose a risk? N Engl J Med. 2006;355(22):2278–2281. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp068157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khamaisi M, Regev E, Yarom N, et al. Possible association between diabetes and bisphosphonate-related jaw osteonecrosis. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2007;92(3):1172–1175. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-2036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khosla S, Burr D, Cauley J, et al. Bisphosphonate-associated osteonecrosis of the jaw: report of a task force of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22(10):1479–1491. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.0707onj. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.The Maxillofacial Center for Diagnostics and Research. [Accessed November 28, 2007];Causes of ischemic bone damage. http://www.maxillofacialcenter.com/NICOcause.html.

- 18.Glueck CJ, McMahon RE, Bouquot JE, Tracy T, Sieve-Smith L, Wang P. A preliminary pilot study of treatment of thrombophilia and hypofibrinolysis and amelioration of the pain of osteonecrosis of the jaws. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1998;85(1):64–73. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(98)90400-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Migliorati CA, Siegel MA, Elting LS. Bisphosphonate-associated osteonecrosis: a long-term complication of bisphosphonate treatment. The Lancet (Oncol) 2006;7(6):508–514. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70726-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gering A, Grange L, Villier C, Woeller A, Mallaret M. Biphosphonates-associated Osteonecrosis of the Jaw: Review on Reported Cases. Therapie. 2007;62(1):49–54. doi: 10.2515/therapie:2007003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krueger CD, West PM, Sargent M, Lodolce AE, Pickard AS. Bisphosphonate-induced osteonecrosis of the jaw. Ann Pharmacotherapy. 2007;41(2):276–284. doi: 10.1345/aph.1H521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Woo SB, Hellstein JW, Kalmar JR. Narrative [corrected] review: bisphosphonates and osteonecrosis of the jaws. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144(10):753–761. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-10-200605160-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carter G, Goss AN, Doecke C. Bisphosphonates and avascular necrosis of the jaw: a possible association. Med J Aust. 2005;182(8):413–415. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2005.tb06761.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marx RE, Sawatari Y, Fortin M, Broumand V. Bisphosphonate-induced exposed bone (osteonecrosis/osteopetrosis) of the jaws: risk factors, recognition, prevention, and treatment. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005;63(11):1567–1575. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2005.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Migliorati CA, Schubert MM, Peterson DE, Seneda LM. Bisphosphonate-associated osteonecrosis of mandibular and maxillary bone: an emerging oral complication of supportive cancer therapy. Cancer. 2005;104(1):83–93. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carter GD, Goss AN. Bisphosphonates and avascular necrosis of the jaws. Aust Dent J. 2003;48(4):268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marx RE. Pamidronate (Aredia) and zoledronate (Zometa) induced avascular necrosis of the jaws: a growing epidemic. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;61(9):1115–1117. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2391(03)00720-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Migliorati CA. Bisphosphanates and oral cavity avascular bone necrosis. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(22):4253–4254. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.99.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shlomi B, Levy Y, Kleinman S, et al. Avascular necrosis of the jaw bone after bisphosphonate therapy. Harefuah. 2005;144(8):536–539. 600, 599. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Najm SA, Lysitsa S, Carrel JP, Lesclous P, Lombardi T, Samson J. Bisphosphonates-related jaw osteonecrosis. Presse Med. 2005;34(15):1073–1077. doi: 10.1016/s0755-4982(05)84119-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hoefert S, Eufinger H. Osteonecrosis of the jaws as a possible adverse effect of the use of bisphosphonates. Mund Kiefer Gesichtschir. 2005;9(4):233–238. doi: 10.1007/s10006-005-0624-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cheng A, Mavrokokki A, Carter G, et al. The dental implications of bisphosphonates and bone disease. Aust Dent J. 2005;50(4 Suppl 2):S4–S13. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2005.tb00384.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Damato K, Gralow J, Hoff A, et al. Expert Panel Recommendations for the Prevention, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Osteonecrosis of the Jaws. June 2004. [Accessed November 28. 2007];American Dental Association. 2004 http://wwwadaorg/prof/resources/topics/topics_osteonecrosis_whitepaperpdf.

- 34.Hess LM. FOIA report, request 2007-5566. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 35.NIH. National Diabetes Statistics. 2005 NIH Publication No. 06-3892.

- 36.Burt VL, Whelton P, Roccella EJ, et al. Prevalence of hypertension in the US adult population. Results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–1991. Hypertension. 1995;25(3):305–313. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.25.3.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ruggiero SL, Mehrotra B, Rosenberg TJ, Engroff SL. Osteonecrosis of the jaws associated with the use of bisphosphonates: a review of 63 cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2004;62(5):527–534. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2004.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Purcell PM, Boyd IW. Bisphosphonates and osteonecrosis of the jaw. Med J Aust. 2005;182(8):417–418. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2005.tb06762.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Marx RE. Oral and Intravenous Bisphosphonate-Induced Osteonecrosis of the Jaws. Chicago: Quintessence Publishing Co.; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Marunick M, Miller R, Gordon S. Adverse oral sequelae to bisphosphonate administration. J Mich Dent Assoc. 2005;87(11):44–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yeo AC, Lye KW, Poon CY. Bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaws. Singapore Dent J. 2005;27(1):36–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Oltolina A, Achilli A, Lodi G, Demarosi F, Sardella A. Osteonecrosis of the jaws in patients treated with bisphosphonates. Review of the literature and the Milan experience. Minerva Stomatol. 2005;54(7–8):441–448. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Merigo E, Manfredi M, Meleti M, et al. Bone necrosis of the jaws associated with bisphosphonate treatment: a report of twenty-nine cases. Acta Biomed. 2006;77(2):109–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dannemann C, Gratz KW, Riener MO, Zwahlen RA. Jaw osteonecrosis related to bisphosphonate therapy A severe secondary disorder. Bone. 2007;40(4):828–834. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2006.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Clarke BM, Boyette J, Vural E, Suen JY, Anaissie EJ, Stack BC., Jr Bisphosphonates and jaw osteonecrosis: the UAMS experience. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;136(3):396–400. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2006.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Farrugia MC, Summerlin DJ, Krowiak E, et al. Osteonecrosis of the mandible or maxilla associated with the use of new generation bisphosphonates. The Laryngoscope. 2006;116(1):115–120. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000187398.51857.3c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang H-L, Weber D, McCauley LK. Effect of long-term oral bisphosphonates on implant wound healing: literature review and a case report. J Periodontol. 2007;78(3):584–594. doi: 10.1902/jop.2007.060239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brooks JK, Gilson AJ, Sindler AJ, Ashman SG, Schwartz KG, Nikitakis NG. Osteonecrosis of the jaws associated with use of risedronate: report of 2 new cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2007;103(6):780–786. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2006.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Heras-Rincon I, Zubillaga Rodriguez I, Castrillo Tambay M, Montalvo Moreno JJ. Osteonecrosis of the jaws and bisphosphonates. Report of fifteen cases. Therapeutic recommendations. Medicina Oral, Patologia Oral y Cirugia Bucal. 2007;12(4):E267–E271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Malden NJ, Pai AY. Oral bisphosphonate associated osteonecrosis of the jaws: three case reports. Br Dent J. 2007;203(2):93–97. doi: 10.1038/bdj.2007.636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Phal PM, Myall RW, Assael LA, Weissman JL. Imaging findings of bisphosphonate-associated osteonecrosis of the jaws. AJNR. 2007;28(6):1139–1145. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A0518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nase JB, Suzuki JB. Osteonecrosis of the jaw and oral bisphosphonate treatment. JADA. 2006;137(8):1115–1119. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2006.0350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pozzi S, Marcheselli R, Sacchi S, et al. Analysis of frequency and risk factors for developing bisphosphonate associated osteonecrosis of the jaw. Blood (ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts) 2005;106 Abst 5157. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Levin L, Laviv A, Schwartz-Arad D. Denture-related osteonecrosis of the maxilla associated with oral bisphosphonate treatment. JADA. 2007;138(9):1218–1220. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2007.0346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Milillo P, Garribba AP, Favia G, Ettorre GC. Jaw osteonecrosis in patients treated with bisphosphonates: MDCT evaluation. La Radiologia Medica. 2007;112(4):603–611. doi: 10.1007/s11547-007-0155-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dimitrakopoulos I, Magopoulos C, Karakasis D. Bisphosphonate-induced avascular osteonecrosis of the jaws: a clinical report of 11 cases. International Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 2006;35(7):588–593. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2006.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Friedrich RE, Blake FA. Avascular mandibular osteonecrosis in association with bisphosphonate therapy: a report on four patients. Anticancer Research. 2007;27(4A):1841–1845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Boyd IW. Therapeutic goods administration, public case detail. Australia: TGA; 2006. [Google Scholar]