Abstract

Objective

To determine if attempts to maximize oocyte yield during ovarian stimulation translates into improved outcome of IVF cycles.

Design

Retrospective.

Setting

Academic tertiary care IVF center.

Patients and intervention

Fresh non-donor IVF cycles (n=806) for the period 1/1/99–12/30/01 were evaluated.

Outcomes

Cycle cancellation-CC, clinical pregnancy- CP, spontaneous miscarriage SAB and live birth- LB following IVF.

Results

Advancing age, independent of ovarian reserve status (reflected by early follicular phase FSH and estradiol) augured a worse prognosis for all outcomes. Higher gonadotropin use, while lowering CC, was associated with significantly reduced likelihood of CP and LB, and a trend towards higher likelihood for spontaneous miscarriage following IVF.

Conclusions

Our data add to the accruing literature suggesting adverse influences of excess gonadotropin use on IVF outcomes. While an aggressive approach to COH results in significant reduction in CC, excessive use of gonadotropins detrimentally influences the eventual outcome of interest i.e. live birth following IVF.

Keywords: In vitro fertilization, Gonadotropin stimulation, Live birth, Clinical pregnancy, Spontaneous miscarriage, Cycle cancellation

Introduction

A progressive rise in follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) levels in association with reproductive aging, concomitant with a decline in the oocyte-granulosa cell repertoire is well recognized (1–4). Poor reproductive success in infertile premenopausal women with biochemical stigmata of diminished ovarian reserve (DOR), such as an elevated FSH level, is also well described (5–12).

A cohort of primordial follicles is committed to growth during any menstrual cycle (13). In an unstimulated cycle, a single follicle commonly achieves dominance, at the expense of the remainder of the cohort. For the purpose of IVF, the aim of controlled ovarian hyperstimulation (COH) is to optimize recruitment and growth of as many of the committed follicular cohort as can be achieved, with due regard to avoiding a risk for ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. The quantitative ovarian response during COH is determined not only by age and infertility diagnosis (i.e. young patients and those with polycystic ovarian syndrome or hypothalamic amenorrhea are recognized as “high responders”) but also by the dose of gonadotropins employed. Suboptimal ovarian responses to exogenous ovarian stimulation, whereby higher dose requirements for gonadotropins result in lower peak estradiol (E2) levels and reduced number of oocytes retrieved, are known accompaniments to declining ovarian reserve. While increasing doses of gonadotropins are shown to lower cycle cancellation (CC) rates (14), potential adverse implications of aggressive COH on pregnancy rates following IVF are emerging (14,15), and a more conservative approach to COH has been suggested (16–17).

The current study was undertaken to evaluate the influence of gonadotropin dose during IVF cycles on outcomes including CC, clinical pregnancy (CP), spontaneous miscarriage (SAB) and live birth (LB). We hypothesized that utilization of excessive doses of gonadotropins would help minimize CC, but at the expense of live birth.

Materials and Methods

All IVF cycles at Montefiore’s Institute for Reproductive Medicine and Health (MIRMH) for the period between January 1999 and December 2001 were identified through the center’s SART database (18). Analysis for the current study was restricted to fresh non-donor ET cycles (n=806). Institutional review board’s approval was obtained for the analysis of de-identified data.

Serum levels of FSH were evaluated in the early follicular phase of the menstrual cycle (cycle days 1–3) by paramagnetic particle immunoassay using the Bayer Immuno-1 analyzer (Tarrytown, NY, inter and intra-assay CV 2.3% and 4.4%, respectively). Maximal historical FSH levels and concomitant E2 levels obtained in a menstrual cycle preceding IVF were utilized to reflect ovarian reserve status. COH was per standard protocols. Briefly, ovarian down regulation was achieved by use of GnRH agonist in a luteal protocol for all except five cycles where pituitary suppression was achieved with a GnRH antagonist. Standard formulations of gonadotropins (75 units per ampoule) were used for COH, and ovarian response was monitored by serial serum E2 assessments and by serial transvaginal ultrasound sonographic (TVS) assessments of ovarian follicular growth. Oocyte maturation was triggered with 10,000 IU of human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), when a minimal of 3 dominant follicles attained a size of 17mm or more. TVS guided oocyte retrieval was performed approximately 34 hours after the hCG injection. Oocyte maturity was evaluated using standard criteria. Evidence for fertilization was assessed approximately 18 hours post insemination. The presence of two pronuclei represented evidence of normal fertilization, whereas 1PN or >2PN were consistent with abnormal fertilization. Transcervical ET was performed under ultrasound guidance on day 3 post insemination. Selection of embryos for fresh ET was based on optimal cleavage status and morphological parameters using standard criteria. Surplus embryos following ET were cryopreserved if meeting defined criteria (progressive cleavage and <25% fragmentation). Luteal support was provided by intramuscular progesterone (P) supplementation (50mgIM daily) until the first pregnancy test 12 days post ET. P supplementation was continued in all cycles with a positive serum βhCG until documentation of fetal cardiac activity by TVS.

The IVF cycle outcomes of interest were CC (initiated IVF cycle cancelled prior to oocyte retrieval due to poor response), CP (positive pregnancy test and a visible intrauterine sac by TVS), SAB (spontaneous pregnancy loss after documentation of CP) and LB (delivery of a live born after 24 completed weeks of gestation).

Statistics

Data distributions were evaluated prior to the analysis. Correlation analyses (Pearson’s for normally distributed and Spearman’s for skewed data) were employed to assess the strength and the direction of associations between COH and patient parameters (age, duration of infertility, dose of gonadotropins, number of eggs retrieved, and embryos cryopreserved or transferred). The associations between outcomes of interest and patient and cycle characteristics (continuous variables) were evaluated using appropriate statistical tests based on data distribution, i.e. Student’s t test (age, FSH level and number of eggs retrieved) or Mann Whitney U test (duration of infertility, number of eggs retrieved, E2 level, dose of gonadotropin used (Units), number of embryos cryopreserved or transferred). The magnitude of association of various patient and cycle characteristics with the outcomes of interest were evaluated using logistic regression analyses, and are reported as odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (95% CI). Multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed to determine independent predictors for the specified outcomes. Decision to include covariates in the adjusted models was based on evidence of significance to an association with the respective outcome on univariate analysis, or biological plausibility to the relationship. For evaluation of CC, all 806 non-donor and fresh ET cycles were analyzed and adjustment variables included age, FSH, E2, duration of infertility (months), dose of gonadotropins (per 100 Units) employed for COH and a history of prior ART (first cycle versus repeat) and diagnoses of “polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS)” and “diminished ovarian reserve”. For assessment of CP and LB, the data analysis was restricted to all non-cancelled cycles that proceeded to egg retrieval (n=640); adjustment variables included age, FSH and E2, duration of infertility (months), dose of gonadotropins (per 100 Units), a history of prior ART (first cycle versus repeat), numbers of eggs retrieved, embryos cryopreserved and embryos transferred. Tertiles were computed for dose of gonadotropins utilized during the analyzed cycles; rates for CP and LB (%) were analyzed across the dose tertiles utilizing Kruskal Wallis rank test. In an attempt to eliminate any potential for bias introduced by a known diagnosis of “diminished ovarian reserve” on outcomes of CP and LB, sensitivity analyses were conducted by repeating multivariate logistic regression analyses after exclusion of IVF cycles in patients with this clinical diagnosis. For the evaluation of predictors of SAB, the covariates included patient’s age, the dose of gonadotropin (per 100 Units) used during COH and the number of embryos transferred. STATA (Intercooled STATA version 8.2, Statacorp, TX) was used for the analyses. P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Of the 806 fresh non-donor IVF cycles undertaken during this study period, a single infertility diagnosis was cited in 563 cycles (69.85%), whereas in the remainder (30.15%), more than one infertility diagnosis was noted. Of cycles with a single diagnosis of infertility, the most common category was tubal disease (162/563, 28.77%), followed by male factor (144/563, 25.57%), diminished ovarian reserve (110/563, 19.53%), unexplained infertility (59/563, 10.47%), PCOS (50/563, 8.88%) and miscellaneous category (38/ 563, 6.74%) that included endometriosis, uterine factor and other causes.

Table 1 presents the overall patient and cycle characteristics. Continuous data are presented as mean ± SD and categorical data as n (%). Almost 21% of the initiated IVF cycles were cancelled prior to egg retrieval (166/806). Of the 640 cycles proceeding to egg retrieval, 28 failed to achieve an embryo transfer (4.4%). The rates for CP and LB respectively were 27.91% (225/806) and 24.06% (194/806) per cycle started, 35.15% (225/640) and 30.31% (194/640) per egg retrieval and 36.76% (225/612) and 31.70% (194/612) per embryo transfer. Following confirmation of CP, 31/225 (13.78%) pregnancies resulted in SAB. No data are available regarding any specific etiology contributing to occurrence of SAB.

Table 1.

Patient and cycle parameters for non-donor fresh embryo transfer IVF cycles (n=806 cycles).

| Parameter | Valuea |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 36.21 ± 4.65 (21.73 – 45.93) |

| FSHb (mIU/ml) | 8.78 ± 3.78 (1 – 33) |

| E2 (pg/ml) | 48.63 ± 35.24 (5 – 437) |

| Gravidity (n) | 1.24 ± 1.49 (0 – 9) |

| Gonadotropin dose (U) | 3584.33 ± 1780.82 (240 – 10,875) |

| Duration of infertility (months) | 50.05 ± 55.20 (0 – 1200) |

| Cycles cancelled %(n) | 20.60 (166/806) |

| Eggs retrieved (n) | 11.38 ± 6.11 (0 – 49) |

| Embryos cryopreserved (n) | 1.88 ± 3.22 (0 – 18) |

| Embryos transferred (n) | 2.97 ± 0.73 (1 – 5) |

Mean ± SD (range).

Maximal reported value for early follicular phase FSH (mIU/ml).

Cycle cancellation

Patient’s age demonstrated statistically significant and positive correlations with FSH levels (r =0.23, p<0.001), increasing utilization of gonadotropin dose (r=0.42, p<0.001) and the number of embryos transferred (r=0.21, p<0.001) and negative correlations with the number of eggs retrieved (r=− 0.22, p<0.001) and embryos cryopreserved (r=− 0.18, p<0.001).

Patient and cycle parameters influencing CC are presented in Table 2. Cancelled cycles were associated with significantly older age (p<0.001) and poorer ovarian reserve (i.e. higher FSH values, p<0.001). The probability of CC was not influenced by the duration of infertility (OR 1.00, p=0.722). Increasing dose of gonadotropins reduced the likelihood of CC, as did a diagnosis of PCOS; conversely, patients with diminished ovarian reserve were almost four times more likely to experience cycle cancellation (p<0.001). Adjusted analysis revealed that adverse influence of FSH levels on CC is independent of age. For each 100U of gonadotropins used, the likelihood of CC decreased by 2% (p=0.029). Patients undergoing their first IVF cycle were almost twice as likely to have CC compared to those undergoing a repeat cycle (p=0.012). PCOS and diminished ovarian reserve emerged as significant determinants of the likelihood for CC, both by univariate and by adjusted analyses (Table 2).

Table 2.

Parameters associated with a risk for cycle cancellation (n=806 cycles).

| Parameters | Unadjusted ORa | P value | Adjusted ORb | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FSHc (mIU/ml) | 1.15 (1.11–1,20) | <0.001* | 1.16 (1.10–1.23) | <0.001* |

| E2 (pg/ml) | 1.00 (1.00–1.00) | 0.008* | 1. 00 (1.00–1.00) | 0.916 |

| Age (years) | 1.10 (1.05–1.15) | <0.001* | 1.07 (1.02–1.13) | 0.004* |

| PCOS | 0.35 (0.19–0.66) | 0.001* | 0.44 (0.20–0.99) | 0.048* |

| Diminished Ovarian Reserved | 3.80 (2.67–5.44) | <0.001* | 1.83 (1.12–3.00) | 0.016* |

| Gonadotropin (per 100units)d | 1.01 (0.99–1.02) | 0.056 | 0.98 (0.97– 0.99) | 0.016* |

| Duration of infertility (months) | 1.00 (0.99–1.00) | 0.910 | 1.00 (0.99–1.00) | 0.648 |

| First IVF cycle (versus repeat) | 1.22 (0.85–1.78) | 0.263 | 1.72 (1.12–2.63) | 0.012* |

Strength of association with cycle cancellation is presented as Odds Ratio (OR) (95% CI).

Univariate analysis

statistically significant.

Multivariate logistic regression determining independent predictors of cycle cancellation after adjustment for specified variables.

FSH: Maximal reported value for early follicular phase FSH (mIU/ml).

Known diagnosis versus other infertility etiologies

Clinical pregnancy

Several parameters were identified as significant determinants of CP following IVF, as demonstrated in Table 3. On univariate analyses, both the age and FSH levels demonstrated significant and negative association with likelihood of achieving CP following IVF. Patients attaining a CP were significantly younger (34.57 ± 4.01 versus 36.86 ± 4.73, p<0.001), and demonstrated significantly better ovarian reserve parameters, i.e. lower FSH and E2 levels (7.59 ± 2.8 and 42.85 ± 17.51 versus 9.26 ± 4.02 and 51.03 ± 40.16, p <0.001 and p=0.003 respectively). A significantly higher likelihood (42%) of achieving CP was noted in the first IVF cycles (p=0.033). All IVF cycles achieving CP demonstrated significantly lower utilization of gonadotropins (3099.78 ± 1484.47 versus 3762.85 ± 1825.27 IU, p<0.001). A 2% decline in the likelihood for achieving a CP was noted for each additional 100IU of gonadotropins used (p <0.001). The number of eggs retrieved and surplus embryos cryopreserved demonstrated positive and significant associations with CP on univariate analysis. Multivariate logistic regression analysis confirmed advancing age and E2 but not FSH levels or dose of gonadotropins used, as significant and negative determinants of CP following IVF. Each additional embryo transferred significantly increases the likelihood of CP by 35% (p=0.039). The significance to earlier observed associations between the first IVF cycle, number of eggs retrieved and embryo cryopreservation was lost in the adjusted analysis. Although a diagnosis of diminished ovarian reserve was associated with a significantly reduced likelihood of achieving CP (p=0.003), and conversely, male factor (p=0.017) and PCOS (p=0.003) were associated with an increased likelihood, statistical significance to these associations disappeared after adjusting for age, FSH and number of embryos transferred (p>0.05) (data not shown).

Table 3.

Parameters predictive of likelihood of clinical pregnancy (n=640 non-cancelled cycles).

| Parameters | Unadjusted ORa | P value | Adjusted ORb | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 0.90 (0.87–0.93) | <0.001* | 0.92 (0.88–0.96) | <0.001* |

| FSHc (mIU/ml) | 0.83 (0.81–0.90) | <0.001* | 0.99 (0.92–1.06) | 0.862 |

| E2 (pg/ml) | 0.99 90.98–0.99) | 0.004 | 0.99 (0.98–0.99) | 0.031* |

| Duration of Infertility (months) | 1.00 (0.99–1.00) | 0.984 | 1.00 (0.99–1.00) | 0.215 |

| Gonadotropin Dose (per 100 units) | 0.98 (0.97–0.99) | <0.001* | 0.98 (0.97–0.99) | 0.039* |

| Eggs Retrieved (n) | 1.03 (1.00–1.06) | 0.010* | 0.98 (0.94–1.02) | 0.525 |

| Embryos Cryopreserved (n) | 1.08 (1.03–1.14) | 0.002* | 1.06 (0.99–1.13) | 0.066 |

| Embryos Transferred (n) | 1.15 (0.91–1.44) | 0.238 | 1.35(1.01–1.80) | 0.039* |

| First IVF cycle (versus repeat) | 1.42 (1.03–1.97) | 0.033* | 1.32 (0.90–1.94 | 0.143 |

Strength of association with clinical pregnancy is presented as Odds Ratio (OR) (95% CI).

Univariate analysis.

statistically significant.

Multivariate logistic regression determining independent predictors of clinical pregnancy after adjustment for specified variables.

Maximal reported value for early follicular phase FSH (mIU/ml).

The inverse association between high dose of gonadotropins and CP remained unaltered in repeated sensitivity analysis after exclusion of IVF cycles in patients with a known diagnosis of diminished ovarian reserve (OR for CP for each 100U of gonadotropin use = 0.98, 95% CI 0.96–0.99); this restricted approach improved the reliability of this association (p=0.006 vs p=0.039) compared to the full model (Table 3).

Live birth

As shown in Table 4, multiple variables demonstrated statistically significant associations with LB following fresh embryo transfer, including age (p<0.001), ovarian reserve (p<0.001), FSH and E2 levels (p=0.005 respectively), gonadotropin dose (p<0.001), and the numbers of eggs retrieved (p=0.003) and embryos cryopreserved (p=0.001). Multivariate adjusted analysis confirmed patient’s age, and early follicular phase E2, but not FSH levels, as independent predictors of LB following fresh ET. The likelihood of achieving LB following IVF decreased by 10% for each additional year increment in age. Higher dose of gonadotropin use demonstrated an adverse association with LB and this relationship maintained statistical significance on adjusted analysis (p=0.014). For each additional 100U of gonadotropin usage, the likelihood of LB decreased by 2%. The number of embryos transferred demonstrated a positive association with successful LB. After adjusting for specified parameters, the likelihood of LB increased by 44% for each additional embryo transferred (p=0.022). The association of LB with the number of eggs retrieved and embryos cryopreserved lost statistical significance in the adjusted model. Similar to the associations noted with CP, a diagnosis of diminished ovarian reserve was associated with a significantly reduced likelihood of achieving LB (p=0.002), and conversely, male factor and PCOS were associated with an increased likelihood (p=0.013 and p=0.014 respectively); statistical significance to these associations disappeared after adjusting for age and FSH (p>0.05) (data not shown).

Table 4.

Factors influencing the likelihood of live birth (n=612 fresh embryo transfers).

| Parameters | Unadjusted ORa | P value | Adjusted ORc | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 0.88 (0.85–0.91) | <0.001* | 0.90 (0.86–0.94) | <0.001* |

| FSHc (mIU/ml) | 0.85 (0.80–0.90) | <0.001* | 0.96 (0.89–1.04) | 0.402 |

| E2 (pg/ml) | 0.98 (0.90–0.99) | 0.005* | 0.98 (0.98–0.99) | 0.027* |

| Duration of infertility (months) | 1.00 (0.99–1.00) | 0.729 | 1.00 (0.99–1.00) | 0.177 |

| Gonadotropins Dose (per 100 units) | 0.93 (0.96–0.98) | <0.001* | 0.98 (0.96–0.99) | 0.014* |

| Eggs retrieved (n) | 1.04 (1.01–1.06) | 0.004* | 0.99 (0.95–1.03) | 0.759 |

| Embryos Cryopreserved (n) | 1.08 (1.03–1.14) | 0.001* | 1.06 (0.99–1.37) | 0.088 |

| Embryos transferred (n) | 1.16 (0.91–1.46) | 0.216 | 1.44 (1.05–1.97) | 0.022* |

| First IVF cycle (versus repeat) | 1.39 (0.98–1.95) | 0.057 | 1.24(0.83–1.85) | 0.277 |

Strength of association with live birth is presented as Odds Ratio (OR) (95% CI).

Univariate analysis.

statistically significant.

Multivariate logistic regression determining independent predictors of live birth after adjustment for specified variables.

Maximal reported value for early follicular phase FSH (mIU/ml).

Similar to the relationship noted for CP, the inverse association between high dose of gonadotropins and LB remained unaltered in repeated analysis performed after exclusion of IVF cycles in patients with a known diagnosis of diminished ovarian reserve (OR for LB for each 100U of gonadotropin use = 0.97, 95% CI 0.96–0.99); if anything, this restricted approach improved both the magnitude (OR for LB= 0.97 versus 0.98) and the reliability (p=0.008 vs p=0.014) for this noted relationship when compared to the full model (Table 4).

Spontaneous miscarriage following clinical pregnancy

Patients experiencing SAB following attainment of CP were significantly older (36.73 ± 4.28 versus 34.43 ± 3.82, p<0.001) compared to those achieving LB. Although a diagnosis of diminished ovarian reserve increased the likelihood of SAB 2 fold (OR 2.08, 95% CI 0.81–5.34), this association was not of statistical significance (p=0.0129). Neither was there any demonstrable relationship with duration of infertility, or first versus repeat cycle (p>0.05, data not shown). Although the cycles culminating in SAB versus LB demonstrated lower number of eggs retrieved (10.93 ± 5.49 versus 12.42 ± 5.51, p=0.119), embryos cryopreserved (1.90 ± 3.44 versus 2.51± 3.51, p=0.290) and embryos transferred (2.96 ± 0.65 versus 3.02 ± 0.57, p=0.773), these differences were not of statistical significance. No relationship was observed between the duration of infertility and likelihood for SAB (p>0.05). While advancing age and the dose of gonadotropins were noted as significant and positive determinants of SAB, the association between SAB and gonadotropin dose lost statistical significance after adjusting for age.

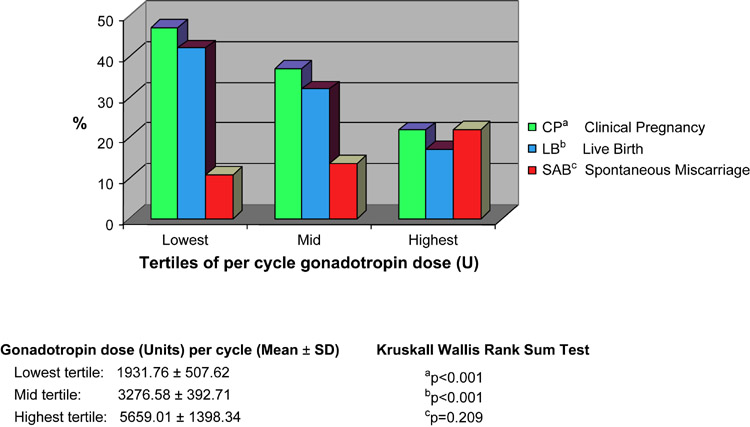

Figure 1 presents the outcomes (CP, LB and SAB) as seen across tertiles for gonadotropin dose. A statistically significant decline in CP and LB was noted with increasing dose of gonadotropins (p<0.001). Although an increasing occurrence of SAB was appreciated from the lowest to the highest tertile of gonadotropin dose, this relationship however was not of statistical significance (p=0.209).

Figure 1.

Worsening of IVF outcomes is notable from the lowest to the highest gonadotropin dose tertile.

Discussion

We herein demonstrate that excessive utilization of gonadotropins for COH reduces cancellation, allowing a higher percentage of cycles to proceed to egg retrieval, albeit at the expense of lowering CP and LB rates. Furthermore, our data imply that high doses of gonadotropins may translate into higher rates for spontaneous miscarriage.

Adverse influences of exogenous gonadotropins on implantation and post-implantation fetal development are reported in rats (19–20). In humans, an increasing utilization of gonadotropins is shown to associate with poor pregnancy rates following IVF (14). Although the exact site of detriment attributable to excess gonadotropins is unclear, adverse influences on the granulosa cells of the developing follicle as well as the oocyte are suggested (22–23). Our data further corroborates an adverse association between excessive gonadotropin exposure during IVF cycles and cycle outcome. Due to the nature of our analysis utilizing an existing database, we are unable to comment on whether the implantation rates were adversely influenced by the gonadotropin dose. In the absence of this latter information, we can only hypothesize regarding the mechanisms influenced by excess gonadotropins, i.e. the developing gamete, the embryo, the endometrium or the metabolic milieu. Indeed, literature supporting each of these mechanisms has been cited (22–24).

We demonstrate that while the early follicular phase levels of FSH are prognostic for cycle cancellation, this marker of ovarian reserve, unlike E2 levels, is of limited value in predicting success of an IVF cycle following ET. This retrospective study thus adds to the growing body of evidence that advancing age rather than the ovarian reserve is the principal determinant of pregnancy following IVF. Although maximal FSH levels were noted to significantly reduce the likelihood of CP and LB in the unadjusted analyses, statistical significance of this association disappeared after adjusting for age. Improved biological potential of the transferred embryos, in cycles where cryopreservation of surplus embryos was attained, is supported by the presented data.

Associations between fetal aneuploidy with advancing maternal age are well established (25). Data describing an association between declining ovarian reserve and elevated risk for chromosomal aberrations are also described (6–8, 25). An increased risk for babies with trisomy 21 is reported in association with maternal FSH levels (6–8) raising the question whether high circulating levels of gonadotropins may play a causative role. Although in vitro evidence of direct toxic effects of FSH on the mitotic spindle assembly and on chromosomal segregation are described, both in oocytes (22) and in granulosa cells (23), these associations are far from substantiated.

A relationship between declining ovarian reserve and an enhanced risk for SAB has been previously suggested (11). Both age and gonadotropin dose utilized for COH demonstrated statistically significant associations with an enhanced likelihood of SAB. A loss of statistical significance to this relationship between gonadotropin dose and SAB in the adjusted model is most likely reflective of power constraints, given the few events (i.e. SAB). Similarly, although SAB following an IVF cycle was twice as likely in patients carrying a diagnosis of diminished ovarian reserve, the lack of statistical significance to this association (p=0.129) is likely reflective of suboptimal power. Consistent with the known relationship between advancing age and risk for miscarriage, patient’s age remained an independent predictor of SAB after adjusting for gonadotropin dose and FSH levels, re-enforcing the validity of our analyses.

Limitations in the study are inherent in the retrospective design and in the use of an existing dataset. Data for the entire sample addresses total IVF cycles for the period rather than cycles per patient. We have attempted to address this deficiency by adjusting for the first versus repeat IVF cycles. A significantly higher likelihood for CC in the first (versus repeat) cycle is likely reflective of a clinical decision that the ovarian response may be maximized in a future cycle. Cycle cancellations were in accordance with our pre-defined protocol for the IVF unit; a minimum of two dominant follicles ≥17mm in diameter and a serum estradiol level of >500pg/ml are required prior to proceeding to egg retrieval; these criteria were implemented and unmodified for the inclusion period and theoretically should have been applicable across all ages. For the period of the study, there was consistency in the COH protocols, laboratory techniques and personnel, thus obviating a major temporal evolution in management strategies impacting on the outcome of IVF in patients enrolled in the latter period of the study. We acknowledge a higher than expected cycle cancellation rate in our patient population (21%) and can partly attribute this to an over-representation of patients with a known diagnosis of diminished ovarian reserve (19%).

Poor response to COH is the most common reason for cycle cancellation in an IVF program. While interpreting the results of baseline FSH levels, it is imperative to distinguish between “likely poor responder” from the “likely poor prognosis for outcome”. Although improved cycle parameters may be achieved by an aggressive approach to COH, i.e. by utilizing escalating doses of gonadotropins, this study allows us to propose a cautious approach to COH, and to retain the focus on the eventual outcome of live birth rather than the intermediate outcome of achieving an egg retrieval.

Conclusions

This study reaffirms that the age of the infertile female remains the principal determinant of the outcome of IVF cycles. Although declining ovarian reserve as evidenced by elevated levels of FSH is associated with a quantitative decline in ovarian response, the prognostic value of FSH levels holds for predicting CC but not pregnancy following fresh ET. The uniformly detrimental association between higher dose of gonadotropins used and significantly lower rates of clinical pregnancy and live birth, as well as a suggestion of higher likelihood for SAB is concerning. These latter associations suggest detrimental influences of excessive gonadotropins that merit further evaluation; in the interim, based on these data, we advise moderation and caution regarding aggressive attempts at COH.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the staff who maintained the SART database during the study period.

This work was supported in part by NIH K12 (to LP)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Capsule:

While an aggressive approach to COH may surmount concerns regarding cycle cancellation, an excess of gonadotropins are detrimental to the eventual outcome of interest i.e. live birth following IVF.

References

- 1.Toner JP, Philput CB, Jones GS, Muasher SJ. Basal follicle stimulating hormone level is a better predictor of in vitro fertilization performance than age. Fertil Steril. 1991;55:784–791. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)54249-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Check JH, Peymer M, Lurie D. Effect of age on pregnancy outcome without assisted reproductive technology in women with elevated early follicular phase serum follicle stimulating hormone levels. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 1998;45:217–220. doi: 10.1159/000009970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chuang CC, Chen CD, Chao KH, Chen SU, Ho HN, Yang YS. Age is a better predictor of pregnancy potential than basal follicle stimulating hormone levels in women undergoing in vitro fertilization. Fertil Steril. 2003;79:63–68. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(02)04562-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.El-Toukhy T, Khalaf Y, Hart R, Taylor A, Braude P. Young age does not protect against the adverse effects of reduced ovarian reserve-an eight year study. Hum Reprod. 2002;17:1519–1524. doi: 10.1093/humrep/17.6.1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scott RT, Opsahl MS, Leonardi MR, Neall GS, Illions EH, Navot D. Life table analysis of pregnancy rates in a general infertility population relative to ovarian reserve and patient age. Hum Reprod. 1995;10:1706–1710. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a136159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nasseri A, Mukerjee T, Grifo JA, Noyes N, Krey L, Copperman AB. Elevated day 3 serum follicle stimulating hormone and/or estradiol may predict fetal aneuploidy. Fertil Steril. 1999;71:715–718. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(98)00525-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Montfrans JM, van Hooff MH, Martens F, Lambalk CB. Basal FSH, estradiol and inhibin B concentrations in women with a previous Down's syndrome affected pregnancy. Hum Reprod. 2002;17(1):44–47. doi: 10.1093/humrep/17.1.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Freeman SB, Yang Q, Allran K, Taft LF, Sherman SL. Women with a reduced ovarian complement may have an increased risk for a child with Down’s syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2000;66:1680–1683. doi: 10.1086/302907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Levi AJ, Raynault MF, Bergh PA, Drews MR, Miller BT, Scott RT., Jr. Reproductive outcome in patients with diminished ovarian reserve. Fertil Steril. 2001;76(4):666–669. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(01)02017-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abdalla H, Thum MY. An elevated basal FSH reflects a quantitative rather than a qualitative decline of the ovarian reserve. Hum Reprod. 2004;19:893–898. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gurbuz B, Yalti S, Ozden S, Ficicioglu C. High basal estradiol level and FSH/LH ratio in unexplained recurrent pregnancy loss. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2004;270(1):37–39. doi: 10.1007/s00404-003-0490-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hanoch J, Lavy Y, Holzer H, Hurwitz A, Simon A, Revel A, et al. Young low responders protected from untoward effects of reduced ovarian response. Fertil Steril. 1998;69:1001–1004. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(98)00079-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Faddy MJ, Gosden RG. A model confirming the decline in the follicle numbers to the age of menopause in women. Hum Reprod. 1996;11:1484–1486. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a019422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hock DL, Louie H, Shelden RM, Ananth CV, Kemmann E. The need to step up the gonadotropin dosage in the stimulation phase of IVF treatment predicts a poor outcome. J Assist Reprod Genet. 1998;15(7):427–430. doi: 10.1007/BF02744936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tan SL, Child TJ, Cheung AP, Fluker MR, Yuzpe A, Casper R, et al. A Randomized, Double-Blind, Multicenter Study Comparing a Starting Dose of 100 IU or 200 IU of Recombinant Follicle Stimulating Hormone (PuregonR) in Women Undergoing Controlled Ovarian Hyperstimulation for IVF Treatment. Journal of Assisted Reproduction and Genetics. 2005;22:81–88. doi: 10.1007/s10815-005-1497-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Hooff MH, Alberda AT, Huisman GJ, Zeilmaker GH, Leerentveld RA. Doubling the human menopausal gonadotrophin dose in the course of an in vitro fertilization treatment cycle in low responders: A randomized study. Hum Reprod. 1993;8:369–373. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a138053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Edwards RG, Lobo RA, Bouchard P. Why delay the obvious need for milder forms of ovarian stimulation? Hum Reprod. 1997;12:399–401. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a019571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Department of Health and Social Services, Center for Disease Control and Prevention; National Summary and Fertility Clinic Reports. ww.cdc.gov/nccdphp/drh/art.htm.

- 19.Miller BG, Armstrong DT. Superovulatory Doses of Pregnant Mare Serum Gonadotropin Cause Delayed Implantation and Infertility in Immature Rats. Biol Reprod. 1981;25:253–260. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod25.2.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ertzeid G, Storeng R. Adverse effects of gonadotrophin treatment on pre- and postimplantation development in mice. J Reprod Fertil. 1992;96:649–655. doi: 10.1530/jrf.0.0960649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ertzeid G, Storeng R, Lyberg T. Treatment with gonadotropins impaired implantation and fetal development in mice. J Assist Reprod Genet. 1993;10:286–291. doi: 10.1007/BF01204944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roberts R, Iatropoulou A, Ciantar D, Stark J, Becker DL, Franks S, et al. Follicle-stimulating hormone affects metaphase I chromosome alignment and increases aneuploidy in mouse oocytes matured in vitro. Biol Reprod. 2005;72:107–118. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.104.032003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaleli S, Yanikkaya-Demirel G, Erel CT, Senturk LM, Topcuoglu A, Irez T. High rate of aneuploidy in luteinized granulosa cells obtained from follicular fluid in women who underwent controlled ovarian hyperstimulation. Fertil Steril. 2005;84:802–804. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sibug RM, Helmerhorst FM, Tijssen AMI, de Kloet ER, Koning Jde. Gonadotropin stimulation reducesVEGF120 expression in the mouse uterus during the peri-implantation period. Hum Reprod. 2002;17:1643–1648. doi: 10.1093/humrep/17.6.1643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Warburton D. Biological aging and the etiology of aneuploidy. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2005;111(3–4):266–272. doi: 10.1159/000086899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]