Abstract

Acetylcholine, acting on presynaptic nicotinic receptors (nAChRs) modulates the release of neurotransmitters in the brain. The rat dorsal raphe nucleus (DR) and the locus coeruleus (LC) receive cholinergic input and express the α7nAChR. In previous reports, we demonstrated that estradiol (E) administration stimulates DR serotonergic and LC noradrenergic function in the macaque. In addition, it has been reported that E induces the expression of the α7nAChR in rats. We questioned whether E increased the expression of the α7nAChR in the macaque DR and LC. We utilized double immunostaining to study the effect of a simulated preovulatory surge of E on the expression of the α7nAChR in the DR and the LC and to determine whether α7nAChR colocalizes with serotonin and tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) in macaques. There was no difference in the number of α7nAChR-positive neurons between ovariectomized (OVX) controls and OVX animals treated with a silastic capsule containing E (Ecap). However, supplemental infusion of E for 5–30 h to Ecap animals (Ecap+inf) significantly increased the number of α7nAChR-positive neurons in DR and LC. In addition, supplemental E infusion significantly increased the number of neurons in which α7nAChR colocalized with serotonin and TH. These results constitute an important antecedent to the study of the effects of nicotine and ovarian steroid hormones in the physiological functions regulated by the DR and the LC in woman.

Keywords: Nicotinic Receptors, Steroid Hormones, Acetylcholine, Serotonin, Noradrenaline

INTRODUCTION

Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) are pentameric ligand-gated ion channels permeable to cations (Lindstrom, 2000). The different subtypes of nAChRs are defined by the composition of their subunits (Lukas et al., 1999). Seventeen nAChR subunit genes have been cloned from vertebrates: α1 to α10, β1 to β4, γ, ε and δ (Le Novère and Changeux, 1995; Elgoyhen et al., 2001). One of the most widely expressed nAChR in the central nervous system is constituted by five α7 subunits (α7nAChR), and has a high affinity for α-bungarotoxin (α–BTX) (Seguela et al., 1993). Presynaptic nAChRs in the central nervous system modulate the release of neurotransmitters (Wonnacott, 1997) like ACh, glutamate (McGehee et al., 1995), serotonin (Seth et al., 2002) noradrenaline (NE) (Cucchiaro and Commons, 2003; Yoshida et al., 1980), GABA (Alkondon et al., 2000) and dopamine (DA) (Champtiaux et al., 2003). However, postsynaptic nAChRs also play important roles; the most clearly demonstrated being the control of ganglionic transmission and fast α7nAChR -mediated synaptic transmission in the hippocampus and in the sensory cortex (Jones et al., 1999).

There is evidence that brain expression of nAChRs may be induced by estradiol (E). There are higher basal levels of nAChRs in the cerebellum of female rats compared to males (Koylu et al., 1997). Furthermore, ovariectomy decreases (Miller et al., 1982) and administration of E increases the densities of α-BTX binding sites (Miller et al., 1984), suggesting that E induces the expression of the α7nAChR in the rat hypothalamus. Moreover, the motivation to self-administer nicotine is greater in female rats than in males (Donny et al., 2000), suggesting a potential interaction of ovarian steroids with nicotine.

Cholinergic neurons of the pedunculopontine tegmental nucleus in the brainstem project widely to numerous targets, including the midbrain dorsal raphe nucleus (DR) and the brainstem locus coeruleus (LC) (Woolf and Butcher, 1989). Both, the DR and the LC express the α7nAChR (Lena et al., 1999; Bitner and Nikkel, 2002; Vincler and Eisenach, 2003). Electrophysiological and pharmacological studies suggest that this receptor stimulates serotonin and NE secretion in the DR (Li et al, 1998), as well as NE secretion in the hippocampus (Vizi and Lendvai, 1999). Moreover, there is evidence that E modulates the stimulatory effect of ACh on serotonin release. Subcutaneous infusion of nicotine increased the concentration of serotonin in the ventromedial nucleus of the rat hypothalamus, but only in presence of E (Zhang et al., 2000). Serotonin neurons contain the β isoform of the E receptor (ERβ) (Gundlah et al., 2001), and E regulates pivotal genes and proteins in serotonin neurons (Bethea et al., 2002). The LC also expresses ERβ (Pau et al., 1998), and E increases the expression of the mRNA for tyrosine hydroxylase (TH, the rate-limiting enzyme in the synthesis of NE) and the release of NE in the LC (Pau et al., 2000).

Hence, there is a body of evidence that both E and ACh modulate serotonin and NE neurotransmission. We questioned whether E could increase the sensitivity of serotonin and NE neurons to ACh by increasing the expression of the α7nAChR. In the present study, we determined whether the expression of the α7nAChR is altered by E treatment in serotonergic neurons of the DR and in NE neurons of the LC of female ovariectomized macaques using fluorescence-based immunocytochemistry.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Ovarian intact rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta), 7–12 years of age and 5.5–6.5 kg in body weight, were individually housed and maintained in quarters kept at temperatures between 21 °C and 25 °C with a 12 L:12 D photoperiod in accordance with NIH guidelines. Monkey chow (Ralston Purina, St. Louis, MO, USA) was provided twice daily and fresh fruit was provided once daily; fresh water was available ad libitum.

Experimental design

Eleven ovarian-intact animals were bilaterally ovariectomized (OVX) and immediately received a 3-cm silastic capsule (0.132 in inner diameter, 0.183 in outer diameter) containing either nothing (OVX, n=4) or crystalline estradiol (Ecap, n=7), implanted subcutaneously. The E implants maintained circulating E levels between 30 and 120 pg/ml, similar to serum E levels during the mid-follicular phase of the monkey menstrual cycle. Four of the seven Ecap rhesus females were injected (1 ml) with 400 ng E/kg body weight followed by 5–30 h of continuous i.v. infusion (1 ml/h) of 320 ng E/kg body weight/h through a femoral vein catheter as described previously (Pau et al., 2000). This E infusion maintained circulating E levels near 300 pg/ml, and was designed to mimic the preovulatory surge of E. The circulating concentrations of E and LH in these animals were previously published (Pau et al., 1993). The E infusion elicited a LH surge at 24 h after initiation of the E infusion. Animals were killed at 0 (OVX and Ecap), 5, 10, 18 and 30 h after initiation of the E infusion (Ecap + 5–30 h inf, one animal per infusion time).

Tissue preparation

Brains were perfused through the ventricular/aorta with 1 liter of 0.9% sodium chloride at room temperature, followed by 3 liters of cold (4 °C) paraformaldehyde (4% in 0.1 M borate, pH 9.5). The midbrains and brainstems were post-fixed and cryoprotected in 20% sucrose-4% paraformaldehyde-0.1 M borate, pH 9.5, for 48–60 h at 4 °C with continuous gentle agitation before they were snap-frozen in a isopentane bath cooled to the temperature of dry ice-ethanol and stored at −80 °C. Frozen brainstems were sectioned on a microtome in a caudal to rostral direction from the caudal end of the LC to the caudal linear nucleus at the level of the substantia nigra. Sections were 20 microns in thickness and serial sections were collected in a cryoprotecting buffer (30% ethylene glycol, 20% glycerol in 0.05 M PBS) as described previously (Pau et al., 2000). Every sixteenth section through the largest extent of the DR and LC (at 320 μm intervals) was selected for this study and care was taken to insure that there was similar representation of the areas from all animals. The region of the DR sampled began at the most rostral tip and extended caudally until the disappearance of the decussation of the cerebellar peduncles. Animals with larger brains yielded slightly more sections. Therefore, in the data analysis, the average number of cells per section was obtained to equalize the analysis. The minimal variance within the groups suggests that the morphology between animals was well matched. All sections were stored at −20 °C until they were double immunostained by specific antibodies against α7nAChR and TH or α7nAChR and serotonin.

Antibody characterization

To localize the α7nAChR, we used the monoclonal antibody mAb306 (gift from Dr. Jon M. Lindstrom, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA) that was generated in mice using affinite purified native chicken and rat α–BTX binding proteins (Schoepfer et al., 1990). Previous studies of epitope mapping reported that the antibody mAb306 recognizes the sequence corresponding to the cytoplasmic loop, residues 380–400, of the α7 subunit from rat (DSGVVCGRLACSPTHDEHLMH) and chicken (DSGVICGRMTCSPTEEENLLH) (Schoepfer et al., 1990; McLane et al., 1992). The specificity of mAb306 was demonstrated initially in rat by Western blot of brain extract, resulting in the staining of a single band of 59 kD molecular weight (Dominguez del Toro et al., 1994).

However, the recent report of cross-reactivity in the α7 knockout mouse raised new questions regarding specificity. Therefore, to further verify the specificity of mAb306 in macaques, we performed a Western blot on an extract of the DR and an adsorption control with a newly synthesized peptide corresponding to the antigenic site (DSGVVCGRLACSPTHDEHLMH). In addition, we examined α7nAChR staining with a new commercial antibody and blocking peptide from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA).

For Western blot, a crude membrane fraction of the DR region from two monkeys was prepared and solubilized as previously described (Smith et al., 2004). The protein concentration of the solubilized membrane preparation was determined with the Bio-Rad protein determination reagent according to the method of Bradford (1976). Samples from one OVX and one Ecap animal containing 25 μg of membrane protein were dissolved in 5% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) containing 4% beta-mercaptoethanol at 80 °C for 15 min and heated at 90 °C for 10 min before being loaded onto a 10% SDS polyacrylamide gel (Jule Biotechnologies). Molecular weight markers (Kalidescope, Biorad) were also included. Transfer to nitrocellulose was performed as published previously (Smith et al., 2004).

The nitrocellulose membrane was blocked in 8% aqueous Carnation nonfat dry milk (Nestle Food Company, Glendale, CA) for 90 min before incubating with the mouse monoclonal anti-α7nAChR antibody mAb306 at a dilution of 1:500 in buffer containing 50 mM Tris and 150 mM NaCl (pH 7.5) at 4 °C overnight. The blots were rinsed in saline and 0.05% Tween-20 (Bio-Rad) and incubated with goat anti-mouse IgG (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) conjugated with horseradish peroxidase at a dilution of 1:5000 in 5% nonfat milk at room temperature for 60 min. Signal was detected by exposing the blot to chemiluminescent film after developing in Supersignal substrate reagents (Pierce, Rockford, IL) followed by exposure to Kodak X-OMAT AR film (Eastman Kodak, Rochester, NY). The bands on the film were captured using an XC-77 CCD video camera (Sony, Towada, Japan) and a framegrabber board on a Mac G4.

To further verify the specificity of the anti-α7nAChR antibody in macaques, an adsorption control with a new antigenic peptide was executed. The peptide antigen to which the antibody is directed was synthesized (Global Peptides, Fort Collins, CO) using the sequence corresponding to the residues 380–400 of the rat α7 subunit (DSGVVCGRLACSPTHDEHLMH).

Then, 1 μl of the anti-α7 subunit antibody mAb306 was incubated overnight with either nothing (non-adsorbed) or 1 mg of the blocking peptide in 975 μl of potassium phosphate-buffered saline (KPBS). Sections of one Ecap+inf macaque were washed in 0.02 M KPBS and exposed for 30 min in a 0.1% hydrogen peroxide solution to eliminate endogenous peroxidase activity. After blocking of nonspecific binding sites with 2% normal donkey serum (NDS, Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA) in 0.4% Triton X-100 for 1 h, sections were incubated for 48 h at 4 °C with either the non adsorbed or the pre-adsorbed anti-α7 subunit antibody mAb306 plus 20 μl NDS and 4 μl Triton X-100. Additional, control sections were processed using BSA (1 mg/ml) in substitution of the primary antibody. Following KPBS washes, sections were incubated in biotin-SP donkey anti-mouse IgG (1:200 in 0.4% Triton X-100, Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) for 1 h at room temperature. Tissues were then incubated for 1 h in avidin-biotin-HRP complex (1:50 in 0.4% Triton X-100, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Visualization was performed using 0.5% diaminobenzidine in 0.02 M KPBS as the chromogen and 0.003% hydrogen peroxide as the substrate, which produces a brown precipitate. Sections were mounted onto Fisher superfrost slides (Fisher Scientific), dehydrated, cleared with Hemo-De (Fisher Scientific) and coverslipped with DPX (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Washington, PA). Sections were examined using a Zeiss Axioplan microscope equipped with bright field illumination and images were captured using a Cool Snap digital camera linked to a Micron PC/Pentium 3 computer.

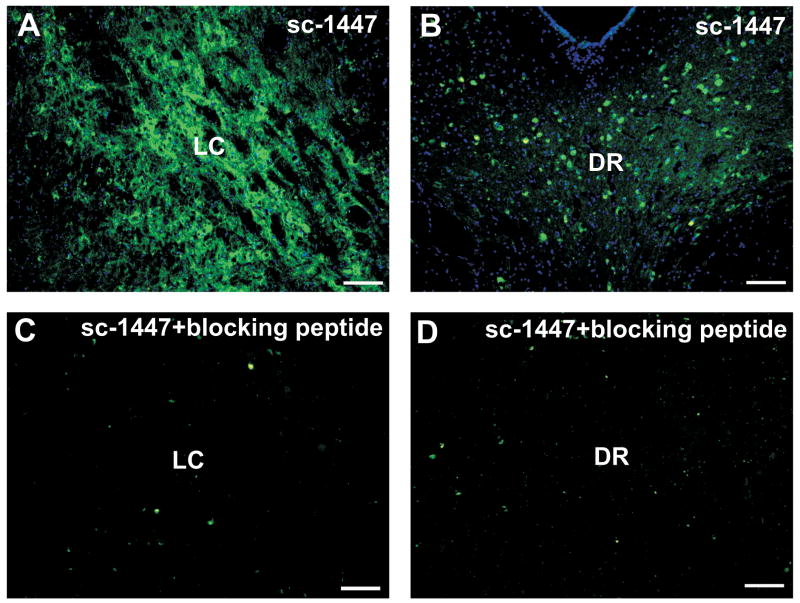

Evaluation of α7nAChR expression using the α7nAChR antibody sc-1447

To further corroborate the expression of the α7nAChR in the areas of interest, we performed an immunofluorescence study using the α7nAChR antibody sc-1447 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) in the presence and absence of blocking peptide provided by Santa Cruz.

The antibody sc-1447 is an affinity purified goat polyclonal antibody raised against a peptide mapping at the C-terminus of the α7nAChR of human origin. The epitope recognized by this antibody was determined by Edmand sequencing of the Santa Cruz blocking peptide (Global Peptides) and corresponds to the residues 482–500 of the α7nAChR of human origin (PubMed accession #NP000737; CTIGILMSAPNFVEAVSKDF). The antiserum stains a single band of approximately 70 kD molecular weight on Western blot (mouse and rat brain SDS extracts electrophoresed through 10% SDS-PAGE gels and electrophoretically transferred to PVDF membranes under reducing conditions by Santa Cruz). All staining was abolished when the primary antibody was preincubated with the immunizing peptide.

Free-floating sections from the LC and DR of one Ecap+inf macaque were washed in 0.02 M KPBS and nonspecific tissue antibody binding sites were blocked by incubating the tissue in 2% NDS in 0.4% Triton X-100 for 1 h at room temperature. Sections were then incubated with a cocktail containing the goat polyclonal anti-α7-subunit antibody sc-1447 at a dilution of 1:100 in 2%NDS in 0.4% Triton for 48 h at 4 °C. The antibody sc-1447 recognizes the sequence corresponding to the residues 482–500 of the human α7 subunit. After KPBS washes, sections were incubated with Alexa Fluor 488 donkey anti-goat IgG (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) at a dilution of 1:200 in 0.4% Triton X-100 for 1 h at room temperature and darkness. Sections were mounted on slides and coverslipped with PVA-DABCO solution (2.5% polyvinyl alcohol-1,4-diazabicyclo[2.2.2]octane in glycerol) (Valnes and Brandtzaeg, 1985).

Control sections were processed by incubating the tissue with the antibody that was pre-adsorbed with a five-fold (by weight) excess of blocking peptide (sc-1447P, Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Additional negative controls were processed by omitting the primary antibody.

α7nAChR/serotonin and α7nAChR/TH double immunofluorescence

Double immunofluorescence was performed to determine whether serotonin or NE neurons express the α7nAChR. Free-floating sections were washed in 0.02 M KPBS and nonspecific tissue antibody binding sites were blocked by incubating the tissue in 2% NDS in 0.4% Triton X-100 for 1 h at room temperature. For serotonin determination, the tissue was incubated after the NDS, with 3% BSA for 1 h. Sections were then incubated with a cocktail containing the mouse monoclonal anti-α7-subunit antibody mAb306 at a dilution of 1:1000, and either the rabbit polyclonal anti-serotonin antibody S5545 (Sigma) at a dilution of 1:1000, or the sheep polyclonal anti-TH antibody AB1542 (Chemicon International, Temecula, CA) at a dilution of 1:2000 in 2% NDS for 48 h at 4 °C. After KPBS washes, sections were incubated with a cocktail of Alexa Fluor 488 donkey anti-mouse IgG and either Alexa Fluor 594 donkey anti-rabbit or Alexa Fluor 594 donkey anti-sheep IgG (Molecular Probes) at a dilution of 1:200 in 0.4% Triton X-100 for 1 h at room temperature and darkness. Following KPBS washes, the tissue was counterstained with Hoechst 3342, trihydrochloride, trihydrate (Molecular Probes). Sections were mounted on slides and coverslipped with PVA-DABCO solution.

Control sections were processed by omitting the primary antibody, and tissue sections from all animals were immunostained together to ensure that the immunochemistry was performed identically for all the groups.

Data processing and statistics

The slides were coded so that the status (OVX, Ecap and Ecap + 5–30 h inf) of the subjects was unknown to the investigator. Sections were examined using a Zeiss Axioplan microscope equipped with fluorescence filters. Serotonin and TH immunoreactivity was identified in the perikarya with the TRITC filter (EX=528–553, DM=565, BA=600–660) as a red immunofluorescence in the cytoplasm. α7nAChR was identified in the perikarya with the FITC filter (EX=465–495, DM=505, BA=515–555) as a green fluorescence in the cytoplasm. The cell nucleus was identified with the DAPI filter (EX=330–380, DM=400, BA=435–485) as a blue immunofluorescence in the nucleus. Immunofluorescence images (TH or serotonin in red, α7nAChR in green, and cell nuclei in blue) across the extent of the DR and LC were captured using a Cool Snap digital camera linked to a Micron PC/Pentium 3 computer. The settings for image capture were standardized by subtraction of background from the control tissue sections (none showed any significant level) and the same exposure time was used for all the groups. Each image was enlarged and the cells were counted from the images on the computer screen. For illustration, images were optimized by adjusting only the brightness and contrast, to the same level in all the groups, before they were overlaid using Adobe Photoshop 7.0 software (Adobe Systems Inc., San Jose, CA). Of note, the immunoflourescence is not visible at lower magnifications, thus our ability to show the entire DR required construction of a collage of numerous higher magnification photographs. A collage of sequential overlaid pictures of α7nAChR+serotonin double-labeled neurons in one section of the DR of two representative monkeys was constructed using the software Adobe Illustrator 8.0 (Adobe Systems Inc., San Jose, CA).

The cytoarchitectonic identification of brainstem regions was based on the stereotaxic atlas of the monkey brain (Paxinos et al., 2000). The number of single-labeled and double-labeled cells was counted bilaterally in the two areas that also correspond to the following plates of the monkey atlas: plates 80–84 for the DR/B7-B6 (rostral areas), and plates 89–97 for the LC/A6. Each area was represented and counted manually bilaterally in 9±3 sections of the DR/B7-B6 and 16±2 sections of the LC/A6 as described previously (Centeno et al., 2004). The area counted in the DR was approximately 640 mm2, and the area counted in the LC area was approximately 770 mm2. The area sampled was the same in all groups, and was controlled with the aid of an ocular micrometer. The distance between adjacent sections was 320 μm. Thus, it is unlikely that the same cell would be represented in two sections. We observed that some cells differed in the intensity of immunolabeling, which may indicate an increment in the expression of the antigen. However, in this work we considered only the number of cells that expressed the antigen and not the density of antigen. The cell was counted as a positive cell if immunostaining (lightly or darkly) was present in the cytoplasm, even if the cell nucleus was not visible in the plane of section. The total number of cells expressing each marker or markers was counted on each section. Then, the section counts were averaged for each animal. Finally, the individual animal means were averaged to obtain the group mean. Thus, the within group variance represents the difference between animals. Changes in cell numbers among groups (OVX, Ecap and Ecap + 5–30 h inf) were determined by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), with post-hoc comparison of group means in the Tukey test. Significance was accepted with a 95% confidence level.

RESULTS

Specificity of the anti-α7 subunit antibody mAb306

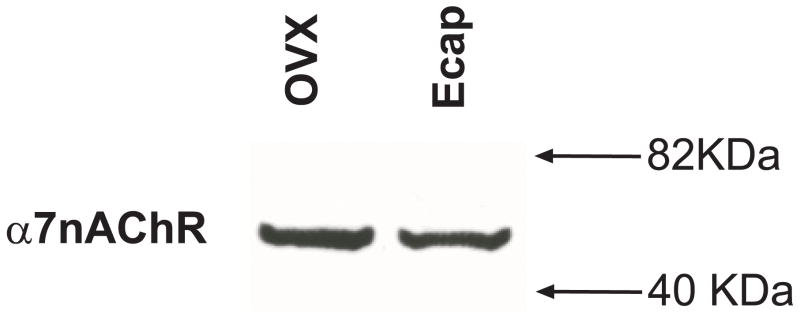

A recent report that mAb306 cross-reacts with a protein in the α7nAChR knockout mouse raised a question regarding its specificity. However, a similar observation was made in the serotonin transporter knock out mouse that was later shown to be a truncated nonfunctional transporter protein (Ravary et al., 2001). Nonetheless, to confirm that the mAb306 recognizes only the α7nAChR subunit in the macaque, we initially performed Western blot analysis on the solubilized membrane fraction of extracts of the DR region from OVX and Ecap animals. Figure 1 shows that the antibody mAb306 stains only one robust band at approximately 60 kDa molecular weight in both animals with no marked difference between treatments.

Figure 1.

Digitized photograph of the autoradiographic film from the Western blot of solubilized membrane preparations of the DR region probed with antibody mAb306. Membrane-bound proteins were extracted from the DR of one OVX and one Ecap macaque. The antibody mAb306 produced only one positive band at approximately 60 kDa molecular weight in both OVX and Ecap macaques that is similar in density.

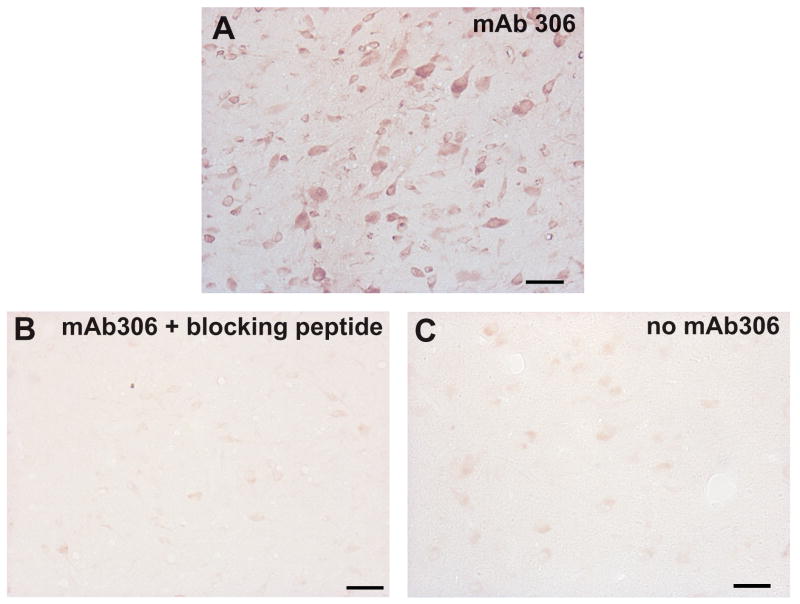

To further corroborate the antibody specificity in immunocytochemistry, we contracted for the synthesis of a peptide corresponding to the reported antigenic epitope of mAb306 (Global Peptides). We then pre-adsorbed the antibody mAb306 with this peptide. Figure 2 illustrates the immunostaining for α7nAChR obtained after incubating sections of one Ecap+inf (5 h) macaque with non-adsorbed antibody (Figure 2A) and the immunoreactivity obtained after exposing the tissue to the antibody pre-adsorbed with 1 mg of its blocking peptide (Figure 2B), versus incubation with BSA instead of the antibody mAb306 (Figure 2C). All staining was abolished when 1 μl of the diluted primary antibody mAb306 was pre-incubated with 1 mg of the immunizing peptide.

Figure 2.

Immunocytochemistry images showing the immunoreactivity for the α7nAChR after the pre-adsorption of the anti-α7nAChR antibody mAb306 with nothing (A) or with a newly synthesized antigenic blocking peptide (B), as well as the nonspecific immunostaining after substitution of the antibody mAb306 with 1 mg/ml BSA (C). Compared with the immunoreactivity obtained with the non pre-adsorbed antibody mAb306 (A), pre-adsorption with the blocking peptide reduced the immunoreactivity (B) to a level observed in the absence of primary antibody (C). Scale bar = 50 μm.

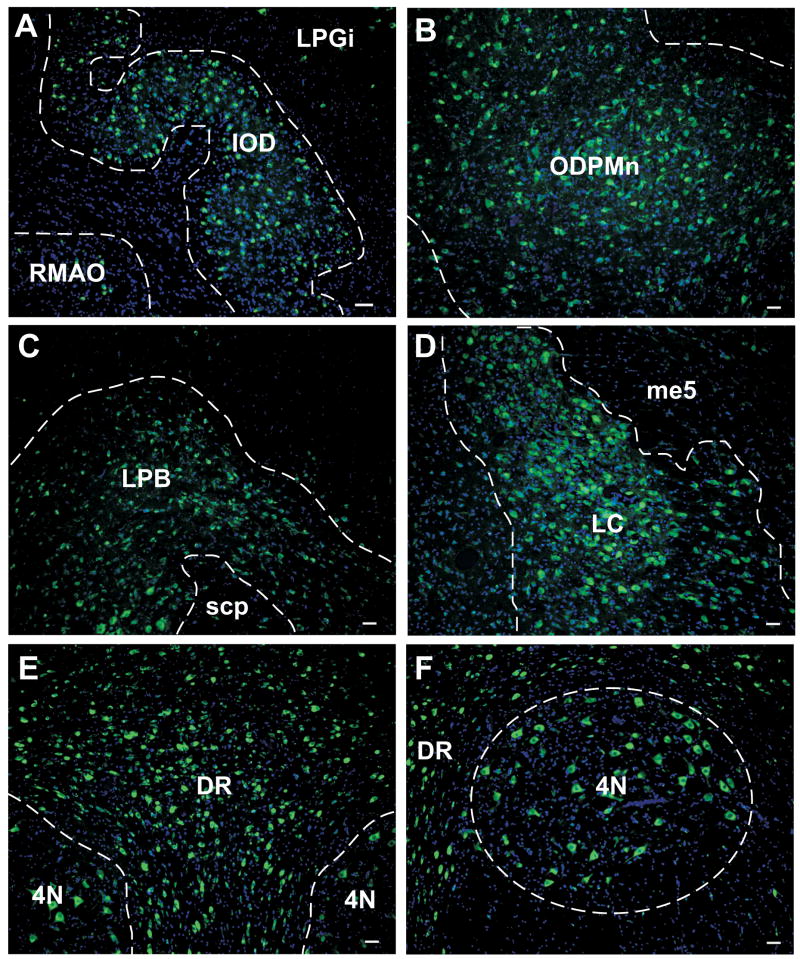

Distribution of α7nAChR in the monkey midbrain and brainstem

With antibody mAb306, we observed that α7nAChR immunoreactivity was widely distributed among several midbrain and brainstem areas. Figure 3 contains immunofluorescent images of different representative areas of one Ecap+inf monkey (10 h) that expressed the receptor. The dorsal nucleus of the inferior olive (IOD) localized at the level of the lateral paragigantocellular nucleus (LPGi) showed some positive cells, but not the rostral medial accessory olive (RMAO, Figure 3A). α7nAChR immunoreactivity was also observed in the oral dorsal paramedian nucleus (ODPMn) (Figure 3B) and the lateral parabrachial nucleus (LPB), indicated at the level of the superior cerebellar peduncle (scp, Figure 3C). All the levels of the locus LC showed numerous α7nAChR-positive cells, as shown in Figure 3D, which represents this area at the level of the mesencephalic 5 tract (me5). In a similar manner, all the levels of the DR exhibited numerous α7nAChR-positive cells. Figure 3E shows an image of the DR at the level of the trochlear nucleus (4N), which also showed α7nAChR immunoreactivity (Figure 3F).

Figure 3.

Distribution of α7nAChR-immunoreactivity (green) in various areas of the midbrain and brainstem of one E-treated monkey. 4N, trochlear nucleus; DR, dorsal raphe nucleus; IOD, dorsal nucleus of the inferior olive; LC, locus coeruleus; LPB, lateral parabrachial nucleus; LPGi, lateral paragigantocellular nucleus; me5, mesencephalic 5 tract; ODPMn, oral dorsal paramedian nucleus; RMAO, rostral medial accessory olive; scp, superior cerebellar peduncle. Scale bar = 50 μm.

The same immunoreactivity pattern was observed using the polyclonal antibody anti-α7nAChR, sc-1447 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Figure 4 shows immunofluorescent images of the LC (4A) and DRN (4B) of one Ecap+inf monkey, followed by their respective pre-adsorbed controls (4C and D). The α7nAChR immunostaining is completely blocked by pre-adsorption of the antibody with the antigenic peptide. The sequence of the blocking peptide was determined by Global Peptides, and corresponded to amino acids 482–500 of the C-terminus of the α7nAChR of human origin.

Figure 4.

Immunofluorescence images showing immunoreactivity for α7nAChR in the LC (A) and DR (B) using the polyclonal antibody sc-1447. Followed by the immunostaining obtained after pre-adsorption of the antibody with its blocking peptide (C and D). Scale bar = 50 μm.

Effect of E on the expression of α7nAChR and serotonin on the monkey DR

Statistical variance within the infused animals was minimal and significantly less (p>0.1) than the variance when compared with the non-infused animals (p<0.01). Hence, the Ecap + 5–30 h inf animals were grouped together (Ecap+inf) and compared to OVX and Ecap animals with ANOVA.

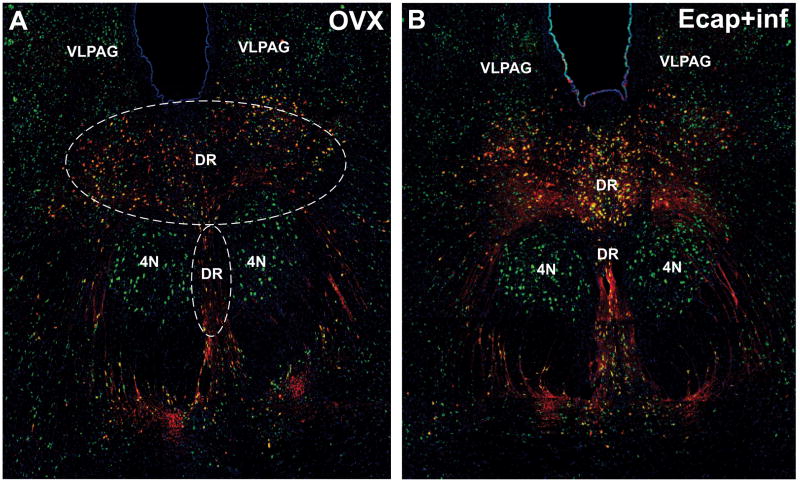

Figure 5 illustrates the distribution of α7nAChR, 5-HT and α7+5-HT double-labeled neurons in one section of the rostral DR of one representative OVX (Figure 5A) and one Ecap+inf monkey (10 h, Figure 5B). The location of the area that was subjected to cell counting is outlined. No apparent difference in the number of α7nAChR-positive cells was observed between treatment groups in other areas adjacent to the DR, like the 4N or the ventrolateral periacueductal gray (VLPAG).

Figure 5.

Collage illustrating the distribution of α7nAChR (green), serotonin (red) and α7nAChR+serotonin co-localization (yellow) in one section corresponding to the rostral part of the DR of one representative OVX (A) and one Ecap+inf monkey (10 h, B). These images were constructed by joining 10x independent overlaid pictures using the software Adobe Illustrator 8.0. Outlined is the representative area in which cells were counted. DR, dorsal raphe nucleus; me5, mesencephalic 5 tract; VLPAG, ventrolateral periacueductal gray.

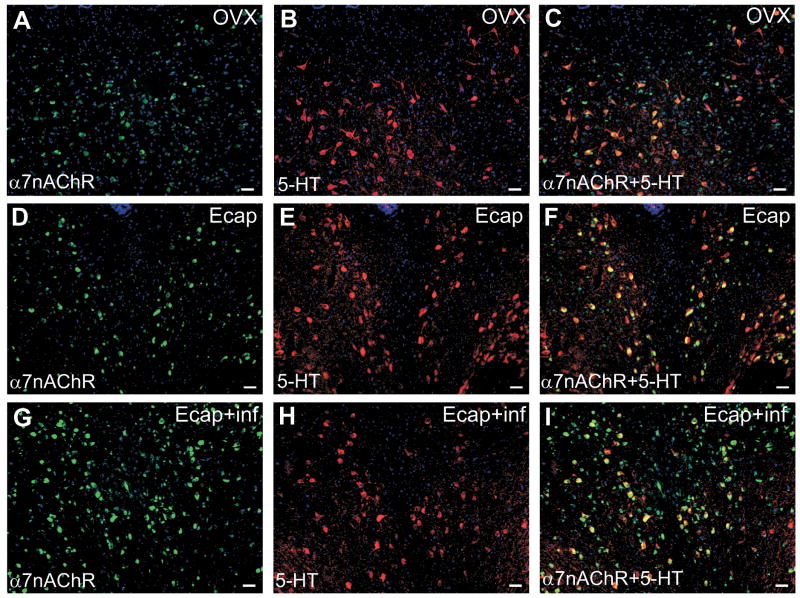

Figure 6 illustrates double-immunofluorescent images showing α7nAChR (green) and serotonin (5-HT, red) immunoreactivity in OVX (Figure 6A–C), Ecap (Figure 6D–F) and Ecap+inf (Figure 6G–I) female macaques. About 70% of 5-HT-positive cells in OVX and Ecap animals also expressed the α7nAChR (Figure 5 and 6, shown in yellow). The mean number of neurons expressing α7nAChR or α7nAChR+5-HT (80% of serotonergic neurons) was higher (p<0.01and p<0.05, respectively; ANOVA and Tukey’s post-hoc pairwise comparison) in the Ecap+inf group compared to the OVX and Ecap groups (Figure 8)

Figure 6.

Double immunofluorescence images that show immunoreactivity for α7nAChR (green; A, D and G), serotonin (5-HT; red; B, E and H) and α7nAChR/serotonin co-localization (yellow; C, F and I) in the DR of a representative OVX (A–C), Ecap (D–F) and Ecap+inf (G–I) monkey. Scale bar = 50 μm.

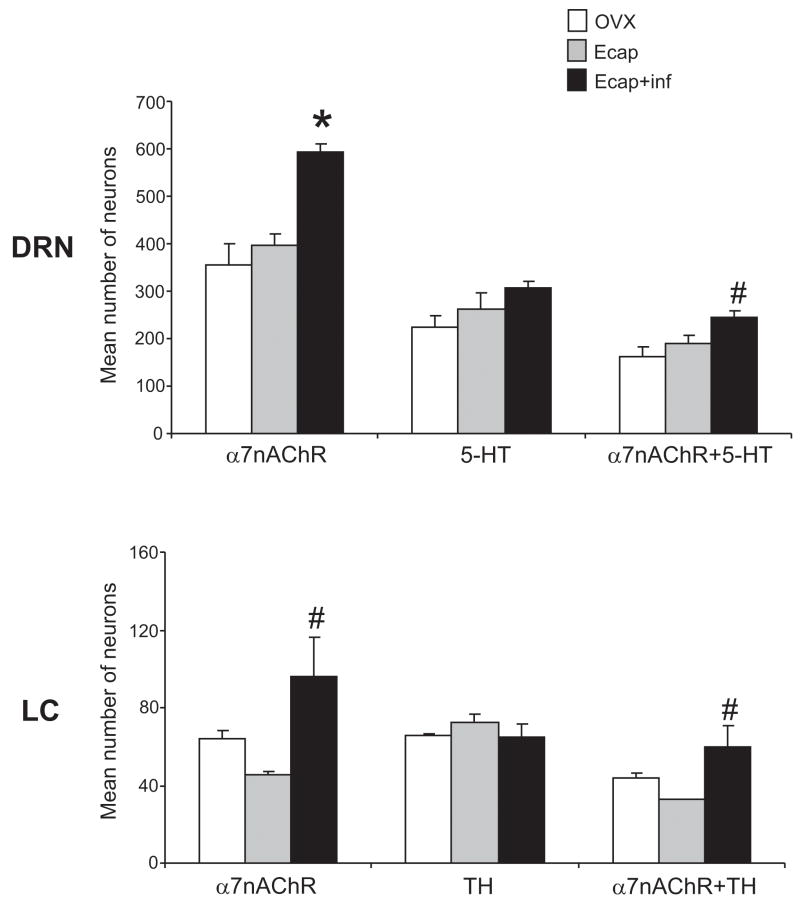

Figure 8.

Histogram illustrating the mean ± S.E.M. of α7nAChR, serotonin (5-HT) or TH immunoreactive cells, and α7nAChR+5-HT or α7nAChR+TH double-labeled neurons in the DR and in the LC of OVX (n=4), Ecap (n=3) and Ecap+inf (n=4) macaques. There was a significant difference in the number of α7nAChR-positive neurons between the treatment groups in both the DR (ANOVA, p<0.0013) and LC (ANOVA, p<0.0293). There was also a significant difference in the number of α7nAChR+5-HT (ANOVA, p < 0.0248) and α7nAChR+TH (ANOVA, p<0.05) between treatment groups. ANOVA was followed by Tukey’s post-hoc pairwise comparison. Asterisks (*) represent a significant increase at p<0.01, and hatch signs (#) represent a significant increase at p<0.05, when compared with the OVX animals.

There was a significant difference in the number of α7nAChR-positive neurons with treatment (p<0.0013, ANOVA and Tukey’s post-hoc pairwise comparison). The number of neurons expressing α7nAChR equaled 355±44 in the OVX group and 397±23 in the Ecap group (ANOVA and Tukey’s, not different). However, the number of α7nAChR-expressing cells increased to 593±15 in the Ecap+inf group (p<0.01, ANOVA and Tukey’s post-hoc pairwise comparison). The number of serotonin-positive neurons equaled 222±26, 262±34 and 305±16 in the OVX, Ecap and Ecap+inf groups, respectively (ANOVA and Tukey’s, not different). There was a significant difference in the number of neurons co-expressing α7nAChR and 5-HT with treatment (p<0.0248, ANOVA and Tukey’s post-hoc pairwise comparison). The number of α7nAChR+5-HT neurons equaled 163±20 in the OVX group and 188±16 in the Ecap group (ANOVA and Tukeys’ not different). However, the number of α7nAChR+5-HT neurons increased to 245±14 in the Ecap+inf group (p<0.05, ANOVA and Tukey’s post-hoc pairwise comparison). As shown in Figure 5, there was also an apparent increase in the number of serotonin-positive fibers between OVX and Ecap+inf groups, however this was not quantified. Neighboring areas were not counted, although we did not observe any obvious differences between the groups (see VLPAG and 4N in Figure 5).

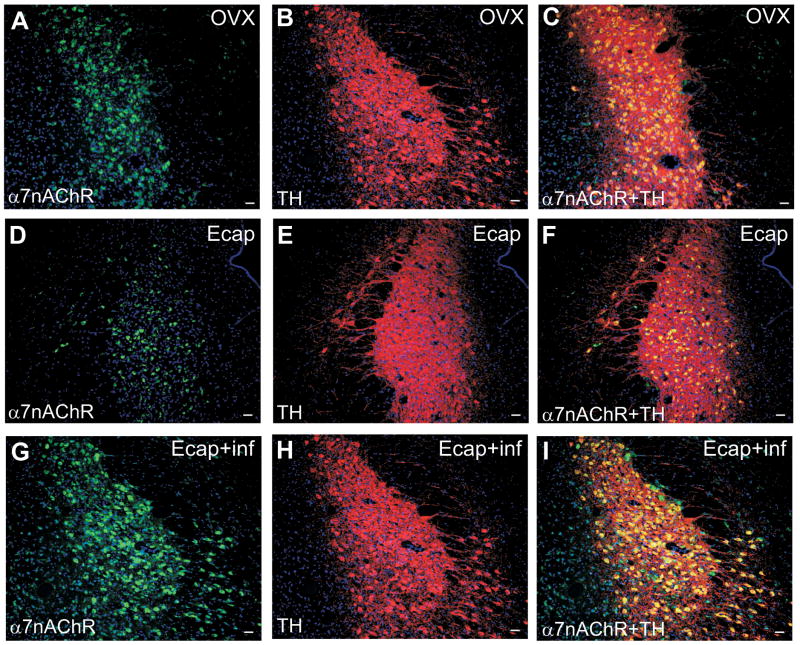

Effect of E on the expression of α7nAChR and TH on the monkey LC

The number of immunoreactive α7nAChR (p<0.0293, ANOVA and Tukey’s post-hoc pairwise comparison) or α7+TH (p<0.05, ANOVA and Tukey’s post-hoc pairwise comparison) neurons was higher in the A6 noradrenergic area of the LC (LC/A6) after E infusion (Figure 7 and 8) as compared with non-infused animals. The number of neurons expressing α7nAChR was 63±4 in the OVX group and 45±1 in the Ecap group (ANOVA and Tukey’s, not different). However, the number of α7nAChR-expressing cells increased to 96±19 in the Ecap+inf group (p<0.05, ANOVA and Tukey’s post-hoc pairwise comparison). The number of TH-positive neurons equaled 65±1, 72±4 and 65±6 in the OVX, Ecap and Ecap+inf groups, respectively (ANOVA and Tukey’s, not different). The number of α7nAChR+TH neurons equaled 43±3 in the OVX group and 32±0.25 in the Ecap group (ANOVA and Tukeys’ not different). However, the number of α7nAChR+TH neurons increased to 60±10 in the Ecap+inf group (p<0.05, ANOVA and Tukey’s post-hoc pairwise comparison). There was no difference in the number of single- or double-labeled neurons in the OVX and Ecap animals. 50% of TH-positive neurons in the OVX and Ecap groups and 90% in the Ecap+inf group expressed α7nAChR. There was no difference in the number of TH-positive neurons in any group and there was no apparent difference in the number of positive cells at the different levels of the LC.

Figure 7.

Double immunofluorescence images that show immunoreactivity for α7nAChR (green; A, D and G), TH (red; B, E and H) and α7nAChR+TH co-localization (yellow; C, F and I) in the LC/A6 area of a representative OVX (A–C), Ecap (D–F) and Ecap+inf monkey (G–I). Scale bar = 50 μm.

DISCUSSION

The goal of this work was to determine the effect of E treatment on the expression of the α7nAChR in serotonergic neurons of the DR and in noradrenergic neurons of the LC in OVX monkeys. We found that administration of E in a concentration similar to that present in the preovulatory phase of the monkey menstrual cycle, significantly increased the number of serotonergic, noradrenergic and other phenotypically un-identified neurons that express the α7nAChR in the DR and LC of OVX macaques.

The two main nAChRs in the brain are the α4β2 and the α7. The α7nAChR has a high affinity for α-BTX and it is widely distributed throughout the nervous system. In this study, we used a monoclonal antibody that recognizes the α7 subunit, named mAb306. A recent report showing cross-reactivity of the mAb306 in a α7nAChR knockout mouse raised the possibility that this antibody exhibits non-specific binding (Herber et al., 2004). Thus, to ensure that mAb306 does not cross-react with proteins other than the α7nAChR subunit in the rhesus macaque brain; we (1) examined a solubilized membrane fraction of the monkey DR region on Western blot and found one robust band, (2) blocked mAb306 labeling with a newly synthesized peptide corresponding to the published antigenic epitope of mAb306, (3) duplicated the staining pattern of mAb306 with a commercial antibody against α7nAChR, (4) completely blocked the staining of the commercial antibody with its blocking peptide, and (5) sequenced the commercial blocking peptide and determined that it corresponds to 18 amino acids in the C-terminal region of human α7nAChR.

We observed one clear band at approximately 60 kD molecular weight indicating that mAb306 does not bind to additional proteins present in our tissue. Moreover, the molecular weight of the α7 subunit ranges in size from 45 to 70 kD, depending on the species studied. There are no reports of the molecular weight of the macaque α7nAChR, but the one band in our monkey DR extracts recognized by mAb306 migrated at a molecular weight similar to that reported for the rat α7nAChR (Dominguez del Toro et al., 1994), further suggesting that the band recognized by mAb306 corresponds to the α7nAChR. Pre-adsorption of mAb306 with a newly synthesized antigenic peptide reduced the intensity of immunolabeling in E-treated monkey DR sections to a level observed in the absence of antibody. Finally, the commercial antibody to α7nAChR yielded the same pattern of staining as mAb306 and this staining was blocked by the respective antigenic peptide, which upon sequencing maps to the C-terminal of the human receptor. Together, these results indicate that mAb306 recognizes one protein, which is likely α7nAChR, in the macaque brain.

We found that the α7nAChR is expressed in several areas, the DR and LC included, of the monkey midbrain and brainstem. This observation is consistent with previous reports of the distribution of this receptor in the brain of several species (Dominguez del Toro et al., 1994; Lena et al., 1999; Quik et al., 2000; Bitner and Nikkel, 2002; Vincler and Eisenach, 2003; Tribollet et al., 2004). The expression of the α7nAChR appears to be regulated by E. In rats, ovariectomy reduces α-BTX binding sites in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (Miller et al., 1982), and the reduction was reversed by E replacement (Miller et al., 1984). In addition, it has been demonstrated that E plays an important role in the hypothalamic expression of nAChRs during development (Block and Billiar, 1979) and puberty (Morley et al., 1983). In this work, we analyzed the effect of E replacement in OVX macaques on the number of serotonin and NE neurons that express the α7nAChR in the DR and LC, respectively. We found that the number of serotonin and NE neurons expressing the α7nAChR increased only after E infusion for 5 to 30 h in a concentration that mimics the preovulatory surge of E, but not in OVX animals with an implant of E. This result suggests that E, in a concentration equivalent to that present in the preovulatory phase of the monkey menstrual cycle, may be participating in the stimulation of the expression of the α7nAChR in serotonergic and NE neurons of the monkey DR and LC, respectively.

In the present work, we observed an increase in serotonergic fibers after E infusion that was not quantified. However, previous work indicates that E increases serotonin synthesis in the DR (Bethea et al., 2002), which may be reflected by the increase in serotonin fiber staining. Also consistent with an earlier report (Bethea, 1994), there was no difference in the number of serotonin-positive neurons with this paradigm of E treatment.

In other studies, we observed that E caused an increase in the mRNA for TH, determined by in situ hybridization (Pau et al., 2000). In this work, we did not find differences in the number of cells expressing the TH protein. Thus, the increase in TH mRNA may be due to regulation of TH expression within the LC neurons and not due to cell recruitment.

It is interesting that the expression of the α7nAChR is induced by E infusion as early as 5 h after the treatment was initiated. There are no reports of time-related changes in the expression of the α7nAChR with E treatment. However, we reported previously that coitus induced the expression of nAChRs in rabbits one hour after mating (Centeno et al, 2004). Whether this expression is induced by E or ACh activity is unknown. Other rapid changes in expression have been noted. For example, acute intermittent nicotine treatment induced fibroblast growth factor-2 mRNA and protein in the rat brain 4 h after the first injection (Belluardo et al., 1998). The molecular mechanism involved in the induction of α7nAChR by E infusion remains to be elucidated and is the aim of future experimentation.

The DR and LC receive cholinergic innervation from the pedunculopontine and laterodorsal tegmental nuclei (McGeer et al., 1986; Woolf and Butcher, 1989), and it has been demonstrated that both the DR and LC express the α7nAChR in the rat (Bitner and Nikkel, 2002). Presynaptic α7nAChRs have been implicated in the modulation of neurotransmitter release, by increasing calcium influx in a concentration sufficient to stimulate vesicular neurotransmitter release in presynaptic terminals from the hippocampal mossy-fibers (Gray et al., 1996). It is possible that α7nAChRs expressed by serotonin neurons in the monkey DR play an important role in the regulation of serotonin release controlled by ACh. There is evidence that serotonin released from the DR is controlled by ACh acting on the α7nAChR (Li et al., 1998; Tucci et al., 2003). In earlier studies, an interaction between brainstem ACh and serotonin neurons was implicated in the control of sleep cycles (Steriade and McCarley, 1990). Zhang et al. (2000) reported that infusion of nicotine increases the concentration of serotonin in the ventromedial nucleus of the hypothalamus in sham-operated but not in OVX rats, suggesting that the stimulatory effect of acetylcholine on serotonin secretion may be affected by E. These reports support the results obtained in this work, indicating that E induces the α7nAChR expression, thereby potentially increasing the sensitivity of serotonin neurons to the stimulatory effect of ACh.

No reports were found suggesting that E acts on ACh-induced NE release. However, it has been reported that nicotine increases the release of NE from rat hypothalamic synaptosomes in vitro (Yoshida et al., 1980). Moreover, cholinergic antagonists attenuated the cold stress-induced increase of TH mRNA in the rat adrenal medulla (Stachowiak et al., 1988) and nicotine inhaled from smoking stimulates NE release from the LC neurons that project to the hippocampus (Vizi and Lendvai, 1999). It has been proposed that ACh may activate presynaptic α7nAChRs located on NE neurons from the LC to facilitate release of NE onto DR neurons (Li et al., 1998). The monkey LC expresses ERβ (Pau et al., 1998), and administration of E to OVX monkeys, in a concentration similar to that found in the preovulatory phase of the monkey menstrual cycle, increased TH mRNA levels in the LC and stimulated NE release in the mediobasal hypothalamus (Pau et al., 2000). Based upon these results, we speculate that the stimulatory effect of E on NE release in the monkey LC may involve the participation of the cholinergic system via the α7nAChR.

We also found that the number of phenotypically un-identified neurons expressing the α7nAChR increased in both the DR and the LC. There are reports of the expression of the α7nAChR in GABAergic neurons of the rat DR and LC (Bitner and Nikkel, 2002). Additional studies reported the presence of non-serotonergic interneurons within local raphe circuits (Aghajanian et al., 1978; Charara and Parent, 1998). It is possible that E is also participating in the ACh regulation of serotonin and NE release via these interneurons. The phenotype of these un-identified neurons is of interest for future study.

Both, the DR and the LC are associated with the regulation of several physiological functions, like food intake (Leibowitz et al., 1984; Schwartz et al., 1989), response to stress (Abercrombie and Jacobs, 1987; Fujino et al., 2002) and reproduction (Lynch et al., 1984, Martins-Afferri et al., 2003). In humans, these functions can be affected by E and nicotine. For example, women appear to benefit more from the weigh-control benefits of smoking than do men (Dicken, 1978). There is a relationship between exposure to tobacco smoke and dysmenorrhea (Chen et al., 2000), and between depression and smoking in woman (Weg et al., 2004). Due to the similarities between humans and non-humans primates, the results obtained in the present work constitute an important antecedent to the study of the interactive effects of nicotine and ovarian steroid hormones on mental health and addiction in women.

In summary, E increased the expression of the α7nAChR in serotonergic, noradrenergic and other non-identified neurons. Thus, the present work provides evidence of the possible participation of E in the sensitivity to ACh in the DR and the LC of the OVX macaque. This could provide an important link between sex steroids and nicotine dependent mood alterations or behaviors.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Jon M. Lindstrom, University of Pennsylvania, for providing the antibody mAb306 against the α7nAChR and to Dr. Harold G. Spies for his comments.

Footnotes

Grant sponsor: NIH; Grant number: MH62677 (to CLB); Grant number: HD30316 (to KYFP); Grant number: RR-00163 and HD-18185 (to ONPRC); Grant sponsor: NIH-Fogarty Foundation Fellowship; Grant number: 517-379 (to MLC).

LITERATURE CITED

- Abercrombie ED, Jacobs BL. Single-unit response of noradrenergic neurons in the locus coeruleus of freely moving cats: I. Acutely presented stressful and nonstressful stimuli. J Neurosci. 1987;7:2837–2843. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.07-09-02837.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aghajanian GK, Wang RY, Baraban J. Serotonergic and non-serotonergic nerurons of the dorsal raphe: reciprocal changes in firing induced by peripheral nerve stimulation. Brain Res. 1978;153:169–175. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(78)91140-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alkondon M, Braga MFM, Pereira EFR, Maelicke A, Albuquerque EX. α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors and modulation of GABAergic synaptic transmission in the hippocampus. Eur J Pharmacol. 2000;393:59–67. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(00)00006-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belluardo N, Blum M, Mudo G, Andbjer B, Fuxe K. Acute intermittent nicotine treatment produces regional increases of basic fibroblast growth factor messenger RNA and protein in the tel- and diencephalon of the rat. Neuroscience. 1998;83:723–740. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00323-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bethea CL. Regulation of progestin receptors in raphe neurons of steroid-treated monkeys. Neuroendocrinology. 1994;60:50–61. doi: 10.1159/000126719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bethea CL, Lu NZ, Gundlah C, Streicher JM. Diverse actions of ovarian steroids in the serotonin neural system. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2002;23:41–100. doi: 10.1006/frne.2001.0225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitner RS, Nikkel AL. Alpha-7 nicotinic receptor expression by two distinct cell types in the dorsal raphe nucleus and locus coeruleus of rat. Brain Res. 2002;938:45–54. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)02485-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Block GA, Billiar RB. Effect of estradiol on the development of hypothalamic cholinergic receptors. Biol Reproduc. 1979;20(Suppl 1):24A. [Google Scholar]

- Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centeno ML, Luo J, Lindstrom JL, Caba M, Pau KYF. Expression of α4 and α7 nicotinic receptors in the brainstem of female rabbits after coitus. Brain Res. 2004;1012:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.03.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Champtiaux N, Gotti C, Cordero-Erausquin M, David DJ, Przybylski C, Lena C, Clementi F, Moretti M, Rossi FM, Le Novere N, McIntosh JM, Gardier AM, Changeux JP. Subunit composition of functional nicotinic receptors in dopaminergic neurons investigated with knock-out mice. J Neurosci. 2003;23:7820–7829. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-21-07820.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charara A, Parent A. Chemoarchitecture of the primate dorsal raphe nucleus. J Chem Neuroanat. 1998;72:111–127. doi: 10.1016/s0891-0618(98)00036-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C, Cho SI, Damokosh AI, Chen D, Li G, Wang X, Xu X. Prospective study of exposure to environmental tobacco smoke and dysmenorrhea. Environ Health Perspect. 2000;108:1019–1022. doi: 10.1289/ehp.001081019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cucchiaro G, Commons KG. Alpha 4 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit links cholinergic to brainstem monoaminergic neurotransmission. Synapse. 2003;49:195–205. doi: 10.1002/syn.10218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dicken C. Sex roles, smoking and smoking cessation. J Health Soc Behav. 1978;19:324–334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominguez del Toro E, Juiz JM, Peng X, Lindstrom J, Criado M. Immunocytochemical localization of the α7 subunit of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor in the rat nervous system. J Comp Neurol. 1994;349:325–342. doi: 10.1002/cne.903490302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donny EC, Caggiula AR, Rowell PP, Gharib MA, Maldovan V, Booth S, Mielke MM, Hoffman A, McCallum Nicotine self-administration in rats: estrous cycle effects, sex differences and nicotine receptor binding. Psychopharmacology. 2000;151:392–405. doi: 10.1007/s002130000497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elgoyhen AB, Vetter DE, Katz E, Rothlin CV, Heinemann SF, Boulter J. alpha10: a determinant of nicotinic cholinergic receptor function in mammalian vestibular and cochlear mechanosensory hair cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:3501–3506. doi: 10.1073/pnas.051622798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujino K, Yoshitake T, Inoue O, Ibii N, Kehr J, Ishida J, Nohta H, Yamaguchi M. Increased serotonin release in mice frontal cortex and hippocampus induced by acute physiological stressors. Neurosci Lett. 2002;320:91–95. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(02)00029-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray R, Rajan AS, Radcliffe KA, Yakehiro M, Dani JA. Hippocampal synaptic transmission enhanced by low concentrations of nicotine. Nature. 1996;383:713–716. doi: 10.1038/383713a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gundlah C, Lu NZ, Mirkes SJ, Bethea CL. Estrogen receptor beta (ERβ) mRNA and protein in serotonin neurons of macaques. Mol Brain Res. 2001;91:14–22. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(01)00108-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herber DL, Severance EG, Cuevas J, Morgan D, Gordon MN. Biochemical and histochemical evidence of nonspecific binding of alpha7nAChR antibodies to mouse brain tissue. J Histochem Cytochem. 2004;52:1367–1376. doi: 10.1177/002215540405201013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones S, Sudweeks S, Yakel JL. Nicotinic receptors in the brain: correlating physiology with function. Trend Neurol Sci. 1999;22:555–561. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(99)01471-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koylu E, Demirgoren S, London ED, Pogun S. Sex difference in up-regulation of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in rat brain. Life Sci. 1997;61:185–190. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(97)00665-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Novère N, Changeux JP. Molecular evolution of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor: an example of multigene family in excitable cells. J Mol Evol. 1995;40:155–172. doi: 10.1007/BF00167110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leibowitz SF, Roossin P, Rosenn M. Chronic norepinephrine injection into the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus produces hyperphagia and increased body weight in the rat. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1984;21:801–808. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(84)80022-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lena C, de Kerchove d’Exaerde A, Cordero-Erausquin M, Le Novère N, Arroyo-Jimenez MM, Changeux JP. Diversity and distribution of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the locus coeruleus neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1999;12:12126–12131. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.21.12126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Rainnie DG, McCarley RW, Greene RW. Presynaptic nicotinic receptors facilitate monoaminergic transmission. J Neurosci. 1998;18:1904–1912. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-05-01904.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindstrom J. The structures of neuronal nicotinic receptors. In: Clementi F, Gotti C, Fornasari D, editors. Neuronal Nicotinic Receptors Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology. Vol. 144. Springer-Verlag; Berlin: 2000. pp. 101–162. [Google Scholar]

- Lukas RJ, Changeux JP, Le Novere N, Albuquerque EX, Balfour DJK, Berg DK, Bertrand D, Chappinelli VA, Clarke PBS, Collins AC, Dani JA, Grady SR, Kellar KJ, Lindstrom JM, Marks MJ, Quik M, Taylor PW, Wonnacott S. International union of Pharmacology. XX. Current status of the nomenclature for nicotinic acetylcholine receptors and their subunits. Pharmacol Rev. 1999;51:397–401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch COJ, Johnson MD, Crowley WR. Effects of the serotonin agonist quipazine, on luteinizing hormone and prolactin release: evidence for serotonin-catecholamine interactions. Life Sci. 1984;13:1481–1487. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(84)90165-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martins-Afferri MP, Ferreira-Silva IA, Franci CR, Anselmo-Franci JA. LHRH release depends on Locus Coeruleus noradrenergic inputs to the medial preoptic area and median eminence. Brain Res Bull. 2003;61:521–7. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(03)00190-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGeer PL, McGeer EG, Peng JH. The cholinergic system of the brain. In: Panula P, Paivarinta H, Soinila S, editors. Neurohistochemistry: Modern Methods and Applications. Liss; New York: 1986. pp. 355–162. [Google Scholar]

- McGehee DS, Heath MJS, Gelber S, Devay P, Role LW. Nicotine enhancement of fast excitatory synaptic transmission in CNS by presynaptic receptors. Science. 1995;269:1692–1696. doi: 10.1126/science.7569895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLane KE, Wu X, Lindstrom JM, Conti-Tronconi BM. Epitope mapping of polyclonal and monoclonal antibodies against two alpha-bungarotoxin-binding alpha subunits from neuronal nicotinic receptors. J Neuroimmunol. 1992;38:115–128. doi: 10.1016/0165-5728(92)90096-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MM, Silver J, Billiar RB. Effects of ovariectomy on the binding of [125I]-αbungarotoxin (2.2 and 3.3) to the suprachiasmatic nucleus of the hypothalamus: An in vivo autoradiographic analysis. Brain Res. 1982;247:355–364. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(82)91261-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MM, Silver J, Billiar RB. Effects of gonadal steroids on the in vivo binding of [125I]alpha-bungarotoxin to the suprachiasmatic nucleus. 1984;290:67–75. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(84)90736-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morley BJ, Rodriguez-Sierra JF, Clough RW. Increase in hypothalamic nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in prepuberal female rats administered estrogen. Brain Res. 1983;278:262–265. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(83)90250-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pau CY, Pau KY, Spies HG. Putative estrogen receptor beta and alpha mRNA expression in male and female rhesus macaques. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1998;146:59–68. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(98)00197-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pau KYF, Berria M, Hess DL, Spies HG. Preovulatory gonadotropin-releasing hormone surge in ovarian-intact rhesus macaques. Endocrinology. 1993;133:1650–1656. doi: 10.1210/endo.133.4.8404606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pau KYF, Hess DL, Kohama S, Bao J, Pau CY, Spies HG. Oestrogen upregulates noradrenaline release in the mediobasal hypothalamus and tyrosine hydroxylase gene expression in the brainstem of ovariectomized rhesus macaques. J Neuroendocrinol. 2000;12:899–909. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.2000.00549.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Huang XF, Toga AW. The rhesus monkey brain in stereotaxic coordinates. Academic Press; San Diego, CA: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Quik M, Polonskaya Y, Gillespie A, Jakowec M, Lloyd GK, Langston JW. Localization of nicotinic receptor subunit mRNAs in monkey brain by in situ hybridization. J Comp Neurol. 2000;425:58–69. doi: 10.1002/1096-9861(20000911)425:1<58::aid-cne6>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravary A, Muzerelle A, Darmon M, Murphy DL, Moessner R, Lesch KP, Gaspar P. Abnormal trafficking and subcellular localization of an N-terminally truncated serotonin transporter protein. Eur J Neurosci. 2001;13:1349–1362. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2001.1511.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoepfer R, Conroy WG, Whiting P, Gore M, Lindstrom J. Brain alpha-bungarotoxin binding protein cDNAs and MAbs reveal subtypes of this branch of the ligand-gated ion channel gene superfamily. Neuron. 1990;5:35–48. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(90)90031-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz DH, McClane S, Hernandez L, Hoebel BG. Feeding increases extracellular serotonin in the lateral hypothalamus of the rat as measured by microdialysis. Brain Res. 1989;479:349–354. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(89)91639-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seguela P, Wadiche J, Dineley-Miller K, Dani JA, Patrick JW. Molecular cloning, functional properties, and distribution of rat brain alpha 7: a nicotinic cation channel highly permeable to calcium. J Neurosci. 1993;13:596–604. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-02-00596.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seth P, Cheeta S, Tucci S, File SE. Nicotinic-serotonergic interactions in brain and behaviour. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2002;71:795–805. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(01)00715-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith LJ, Henderson JA, Abell CW, Bethea CL. Effects of ovarian steroids and raloxifene on proteins that synthesize, transport, and degrade serotonin in the raphe region of macaques. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;29:2035–2045. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stachowiak M, Stricker EM, Zigmond MJ, Kaplan BB. A cholinergic antagonist blocks cold stress-induced alterations in rat adrenal tyrosine hydroxilase mRNA. Mol Brain Res. 1988;3:193–196. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(88)90066-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steriade M, McCarley RW. Brainstem control of wakefulness and sleep. Plenum Press; New York, NY: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Tribollet E, Bertrand D, Marguerat A, Raggenbass M. Comparative distribution of nicotinic receptor subtypes during development, adulthood and aging: an autoradiographic study in the rat brain. Neuroscience. 2004;12:405–420. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2003.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucci SA, Genn RF, File SE. Methyllycaconitine (MLA) blocks the nicotine evoked anxiogenic effect and 5-HT release in the dorsal hippocampus: possible role of α7 receptors. Neuropharmacology. 2003;44:367–373. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(02)00391-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valnes K, Brandtzaeg P. Retardation of immunofluorescence fading during microscopy. J Histochem Cytochem. 1985;33:755–761. doi: 10.1177/33.8.3926864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincler MA, Eisenach JC. Immunocytochemical localization of the α3, α4, α5, α7, β2, β3 and β4 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunits in the locus coeruleus of the rat. Brain Res. 2003;974:25–36. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(03)02546-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vizi ES, Lendvai B. Modulatory role of presynaptic nicotinic receptors in synaptic and non-synaptic chemical communication in the central nervous system. Brain Res Rev. 1999;30:219–235. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(99)00016-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weg MW, Ward KD, Scarinci IC, Read MC, Evans CB. Smoking-related Correlates of Depressive Symptoms in Low-Income Pregnant Women. Am J Health Behav. 2004;28:510–521. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.28.6.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wonnacott S. Presynaptic nicotinic ACh receptors. Trends Neurosci. 1997;20:92–98. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(96)10073-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolf NJ, Butcher LL. Cholinergic systems in the rat brain: IV. Descending projections of the pontomesencephalic tegmentum. Brain Res Bull. 1989;23:519–540. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(89)90197-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida K, Kato Y, Imura H. Nicotine-induced release of noradrenaline from hypothalamic synaptosomas. Brain Res. 1980;182:361–368. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(80)91194-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Varna M, Meguid MM. Changes in hypothalamic monoamines with nicotine in menopausal females: implications in food intake and body weight regulation. Surg Forum. 2000;51:419–421. [Google Scholar]