The Canadian Hypertension Education Program (CHEP) has the mandate of reducing the burden of cardiovascular disease in Canada through optimized hypertension management. The process of screening, diagnosing, treating, and monitoring hypertension on an ongoing basis generates the single greatest number of family physician office visits in Canada—more than 20 million visits annually.1 This represents a substantial workload for physicians. Complicating the matter is the fact that approximately 15% of the Canadian population currently does not have a family physician. Moreover, the prevalence of diagnosed hypertension is growing: approximately 1 in 4 Canadians is affected and this is expected to increase. In those older than 50 years of age, a recent Canadian population analysis reports the prevalence of hypertension as greater than 50%.2 In a national survey done between 1986 and 1992, only a minority of patients with hypertension were identified, treated, and controlled to their recommended blood pressure target.3

Rates of hypertension control have improved, according to a recent survey in Ontario, but at least 30% of Ontarians 18 years of age or older were still either uncontrolled or not identified.4 For these reasons, the Implementation Task Force (ITF) of CHEP felt it would be beneficial to acknowledge the existing care gap in the management of hypertension and encourage primary health care professionals to further integrate and coordinate their efforts with the ultimate goal of decreasing the burden of cardiovascular disease. Given the prevalence of hypertension and the large patient care demands already placed on family physicians, one solution for the screening and care of patients with hypertension is to take full advantage of the special knowledge, skills, and abilities of other members of the health care team.

The ITF committee comprises 3 primary care subgroups: family physicians, nurses, and pharmacists. At the annual ITF meeting in September 2007, it was identified that the collaboration of various health care professionals can be hindered by the lack of clarity regarding the role of each professional group in the management of patients with hypertension. Given the multidisciplinary nature of CHEP and the ITF, we felt it was important for us to endorse interdisciplinary collaboration and explore how it could be further enhanced. Currently, there is little data to demonstrate if or how collaborative care affects patient outcomes; however, it seems intuitive that hypertension control will be enhanced if all team members’ special skill sets are used to the fullest. The family physician has traditionally been central to the coordination of care for the patient. The changing scope of practice for nurses, nurse practitioners, and pharmacists, however, is facilitating their greater involvement in chronic disease management. Further, increasing numbers of patients with hypertension coupled with the demands on family physicians suggests that collaboration in care is essential. Although interdisciplinary teams (such as primary care networks or family health teams) either exist or are being created to incorporate other health professionals into primary health care, this concept is still in its infancy and likely affects a minority of patients with hypertension. Instead, the bulk of care is happening at the traditional family practice level in which the infrastructure and financial resources to facilitate routine interdisciplinary care are lacking.

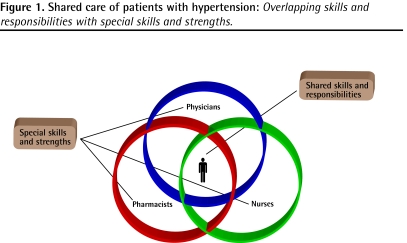

The intent of this paper is to generate discussion on how we can collaboratively improve care in our respective communities by sharing responsibility, with the common goal of improving hypertension management in Canada. In doing so, we hope to identify gaps in our current knowledge that might help researchers. We hope that our endorsement of interdisciplinary collaboration will encourage further research aimed at determining whether such collaboration results in enhanced outcomes for patients with hypertension. We acknowledge the overlapping roles among physicians, nurses, and pharmacists; this paper will highlight the unique skill set of each group, which can contribute to enhanced patient management (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Shared care of patients with hypertension: Overlapping skills and responsibilities with special skills and strengths.

Shared care

It is important to emphasize that all health professional groups must work toward optimizing hypertension prevention, detection, lifestyle modification, treatment, and adherence. Coordination of services in the diverse array of community settings where patient care can be most efficiently provided is likely to provide the best patient outcomes; this reinforces the importance of integrating the skills and knowledge of nurses, pharmacists, and physicians. The overlapping skill sets of each profession can facilitate optimal use of health care resources by allowing various care delivery options.

Each health care professional has training that allows him or her to make a unique contribution to patient care decisions; the concept that the “whole is greater than the sum of its parts” should be embraced. Physicians, nurses, and pharmacists are all capable of obtaining an accurate blood pressure measurement, but the management plan for an individual patient is often dependent on a variety of other factors. Each practitioner can play a key role in identifying, communicating, and taking responsibility for the collective treatment plan. It is expected that any patient information affecting the treatment plan be appropriately documented and communicated with all team members; CHEP supports and encourages shared responsibility for patients with or at risk for hypertension.

Table 1 highlights some of the skill sets among health professional groups; although this list is not intended to be all-inclusive, it represents a starting point for initiating discussion within the primary care community. We believe it is important to provide uniform messages tailored to each patient and his or her expectations and to effectively communicate the ongoing care concerns for our shared patients.

Table 1.

Attributes most appropriately aligned with each health professional group: A focus on physicians, nurses and nurse practitioners, and pharmacists.

| HEALTH CARE GROUP | ATTRIBUTES |

|---|---|

| Physicians |

|

| Nurses and nurse practitioners |

|

| Pharmacists |

|

Building blocks

The burden of hypertension, both detected and undetected, is too great for health care professionals not to work together for the sake of the patients, whom we all serve. Underdetection, issues of patient adherence and clinical inertia, and the complexity of treatment in the presence of other diseases impede our ability to gain better control rates nationally. By sharing responsibility with other health care professionals, like nurses and pharmacists, we can shift some of the burden of care from the family physician. Indeed, a recent systematic review concluded that using a team approach in the treatment of hypertension was the single most effective intervention to improve quality of care.5

Pharmacists, nurses, and other appropriate health care providers must be ready and willing to accept additional responsibility, but they also need to feel empowered to take on additional tasks. In addition, patients need to be educated about expectations from various health care professionals and how these groups can have a greater role and responsibility for their care. The ultimate goal is to enable patients to become ambassadors for their own hypertension management and to approach the appropriate health care professional for ongoing support and education when required.

The Romanow Report,6 released in 2002, identified 4 essential building blocks for the delivery of primary health care. These included continuity of care, early detection and action, better information on needs and outcomes, and stronger incentives and approaches for health care providers to participate in primary care. The report also emphasized the importance of collaborative teams and networks in future primary care models. Making this happen effectively is now our collective responsibility. We need to stop talking about it and start doing it.

Each year CHEP has done an excellent job updating the recommendations on the screening, diagnosis, and treatment of hypertension. Moreover, CHEP has endorsed the development of profession-specific guidelines for hypertension management with family physicians,7,8 pharmacists,9 and nurses.10 Evidence-based recommendations to assist patients in understanding and managing hypertension have also been developed.11 These guidelines encourage shared care and responsibility-taking, and provide accurate and timely information to support good management decisions for our patients. The CHEP website, www.hypertension.ca, contains many resources for health care providers and patients alike. Using these tools and incorporating them into your practice will provide an excellent framework for many relevant discussions.

All in all

The 2008 Annual Update to the CHEP guidelines promotes empowering patients to be more involved in their own self-management. Successfully achieving this will require the united efforts of all primary health care providers. Communication among team members will be of paramount importance, so that treatment goals are clearly understood, aligned, and reinforced by all team members. We encourage local groups, including other health care professionals such as dietitians, social workers, and exercise therapists, to begin this dialogue. It is important to develop communication techniques that will work in each specific setting. We challenge you to think about the way you currently provide care and whether or not you are maximizing the benefits of a collaborative, multidisciplinary approach to hypertension management.

Consider these questions..

Think about the way you currently provide care, and ask yourself the following questions:

Do I routinely screen all my patients for hypertension?

Do I routinely screen for hypertension in patients known to be high risk (eg, patients with diabetes, patients with a history of coronary artery disease)?

Do I routinely discuss important lifestyle modifications to decrease the risk of hypertension?

Ask yourself the following questions when treating patients with hypertension:

Are treatment goals documented?

Do my patients know how to properly measure their blood pressure at home?

Do my patients adhere to medication and lifestyle recommendations?

Are treatment goals maintained over the long term?

Footnotes

Competing interests

Ms Thompson has participated on advisory boards for Sanofi-Aventis and Astellas Pharma, and in a hypertension workshop for Pharmascience. Dr Campbell gives speeches, sits on advisory boards, and provides expert advice for most of Canada’s Reasearch-Based Pharmaceutical Companies (Rx&D) that produce anithypertensive drugs in Canada.

The opinions expressed in commentaries are those of the authors. Publication does not imply endorsement by the College of Family Physicians of Canada.

Cet article se trouve aussi en français à la page 1664.

References

- 1.Hemmelgarn BR, Chen G, Walker R, McAlister FA, Quan H, Tu K, et al. Trends in antihypertensive drug prescriptions and physician visits in Canada between 1996 and 2006. Can J Cardiol. 2008;24(6):507–12. doi: 10.1016/s0828-282x(08)70627-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tu K, Chen C, Lipscombe LL Canadian Hypertension Education Program Outcomes Research Taskforce. Prevalence and incidence of hypertension from 1995 to 2005: a population-based study. CMAJ. 2008;178(11):1429–35. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.071283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Joffres MR, Ghadirian P, Fodor JG, Petrasovits A, Chockalingam A, Hamet P. Awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in Canada. Am J Hypertens. 1997;10(Pt 1):1097–102. doi: 10.1016/s0895-7061(97)00224-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leenen FH, Dumais J, McInnis NH, Turton P, Stratychuk L, Nemeth K, et al. Results of the Ontario survey on the prevalence and control of hypertension. CMAJ. 2008;178(11):1441–9. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.071340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walsh JM, McDonald KM, Shojania KG, Sundaram V, Nayak S, Lewis R, et al. Quality improvement strategies for hypertension management: a systematic review. Med Care. 2006;44(7):646–57. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000220260.30768.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Romanow RJ. Building on values. The future of health care in Canada. Saskatoon, SK: Commission on the Future of Heath Care in Canada; 2002. [Accessed 2008 May 20]. Available from: www.hc-sc.gc.ca/hcs-sss/alt_formats/hpb-dgps/pdf/hhr/romanow-eng.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Padwal RJ, Hemmelgarn BR, Khan NA, Grover S, McAlister FA, McKay DW, et al. The 2008 Canadian Hypertension Education Program recommendations for the management of hypertension: part 1—blood pressure measurement, diagnosis and assessment of risk. Can J Cardiol. 2008;24(6):455–63. doi: 10.1016/s0828-282x(08)70619-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khan NA, Hemmelgarn B, Herman RJ, Rabkin SW, McAlister FA, Bell CM, et al. The 2008 Canadian Hypertension Education Program recommendations for the management of hypertension: part 2—therapy. Can J Cardiol. 2008;24(6):465–75. doi: 10.1016/s0828-282x(08)70620-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsuyuki RT, Semchuk W, Poirier L, Killeen RM, McAlister MA, Campbell N, et al. Canadian Hypertension Education Program guidelines for the management of hypertension by pharmacists. [Accessed 2008 Oct 28];CPJ. 2006 2006 139(3 Suppl 1):511–3. Available from: www.hypertension.ca/chep/wp-content/uploads/2007/10/chep-2006-guidelines-for-pharmacists.pdf.

- 10.Heart and Stroke Foundation of Ontario, Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario. Nursing management of hypertension. Toronto, ON: Heart and Stroke Foundation of Ontario and Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario; 2005. [Accessed 2008 Aug 12]. Available from: www.rnao.org/Storage/11/607_BPG_Hypertension.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blood Pressure Canada, Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada, Canadian Hypertension Education Program, Canadian Hypertension Society, Societe Quebecoise d’hypertension arterielle. [Accessed 2008 Aug 12];Hypertension. 2008 public recommendations. Available from: http://hypertension.ca/bpc/wp-content/uploads/2008/02/2008publicrecommendations.pdf.