Abstract

Worldwide fisheries generate large volumes of fishery waste and it is often assumed that this additional food is beneficial to populations of marine top-predators. We challenge this concept via a detailed study of foraging Cape gannets Morus capensis and of their feeding environment in the Benguela upwelling zone. The natural prey of Cape gannets (pelagic fishes) is depleted and birds now feed extensively on fishery wastes. These are beneficial to non-breeding birds, which show reduced feeding effort and high survival. By contrast, breeding gannets double their diving effort in an attempt to provision their chicks predominantly with high-quality, live pelagic fishes. Owing to a scarcity of this resource, they fail and most chicks die. Our study supports the junk-food hypothesis for Cape gannets since it shows that non-breeding birds can survive when complementing their diet with fishery wastes, but that they struggle to reproduce if live prey is scarce. This is due to the negative impact of low-quality fishery wastes on the growth patterns of gannet chicks. Marine management policies should not assume that fishery waste is generally beneficial to scavenging seabirds and that an abundance of this artificial resource will automatically inflate their populations.

Keywords: biotelemetry, dispersal, fishery discard management, foraging behaviour, industrial fisheries, scavenger

1. Introduction

Human fisheries substantially perturb marine ecosystems through destruction of marine habitats, removal of organisms from higher trophic levels, accidental by-catch of non-target species and dumping of fishery wastes (Jennings et al. 2001). Fishery wastes include offal generated when processing fishes at sea, as well as discarded undersized fishes and non-target species. The amount of fishery waste produced is substantial: approximately 7.3 million tonnes of discards are returned to the sea annually by worldwide fisheries (Kelleher 2005). This additional food source affects food web structures, as it favours scavengers throughout the water column and on the seabed (Catchpole et al. 2006). For some marine top-predators such as seabirds and marine mammals, fishery wastes provide an alternative food source; they can forage on both live prey and fishery wastes, eventually favouring the latter when the former becomes scarce (Votier et al. 2004). Some seabird populations benefit greatly from current dumping practices and are artificially inflated (Garthe et al. 1996; Furness 2003). It is therefore often assumed that fishery waste is beneficial to seabirds (Garthe & Hüppop 1994; Tasker et al. 2000; Montevecchi 2002). We challenge this concept through a detailed study of the year-round foraging behaviour of an avian top-predator, the Cape gannet (Morus capensis), which feeds on live prey and fishery wastes in the Benguela upwelling ecosystem.

The Benguela is one of the four major upwelling zones of the world's oceans, located along the Atlantic coasts of Namibia and South Africa. Its productive waters are traditionally home to vast biomasses of pelagic fishes such as anchovy (Engraulis encrasicolus) and sardines (Sardinops sagax), which support a large community of predatory fishes, seabirds and marine mammals (Shannon 1985). Anchovies, sardines and predatory fishes such as hake (Merluccius spp.) are also targeted by human fisheries (Griffiths et al. 2004). The South African hake fishery currently produces some 52 500 tonnes of waste per year in the form of discards and offal (Walmsley et al. 2007).

With approximately 500 000 breeding individuals, weighing on average 2.6 kg, Cape gannets are major avian predators in the Benguela (Crawford 2005). They feed primarily by plunge-diving on pelagic fishes within the first 20 m of the water column (Crawford 2005), but also gather behind hake trawlers to feed on fishery wastes (Abrams 1983; Ryan & Moloney 1988). Such food has only half the calorific value of Cape gannets' natural prey (Batchelor & Ross 1984). In this context, the junk-food hypothesis (JFH) posits that seabirds feeding on prey of low energy and nutrient content have reduced reproductive success (Piatt & Anderson 1996), because such a diet affects the growth patterns and the cognitive abilities of their offspring (Kitaysky et al. 2005; Wanless et al. 2005). The JFH has so far been tested for seabirds and marine mammals facing natural changes in diet quality, for instance after an ecosystem shift (Rosen & Trites 2000; Litzow et al. 2002; Jodice et al. 2006). Nevertheless, it might also apply to marine predators feeding on energetically poor fishery wastes (Pichegru et al. 2007). Furthermore, previous tests of the JFH addressed either the fate of non-breeding adults or that of their young during the reproductive phase, but did not study one species on a year-round basis.

Here we examine the JFH during the reproductive and non-reproductive phases of a seabird foraging on live prey and/or fishery wastes. We used year-round, parallel datasets of hake trawler distribution, Cape gannet diet, Cape gannet movements and foraging behaviour recorded by bird-borne miniaturized data loggers, as well as assessments of Cape gannet breeding success. More specifically, we test the prediction that abundant fishery waste is beneficial to non-breeding birds, but not to birds raising chicks.

2. Material and methods

All measurements were performed in the southern Benguela upwelling zone under permits issued by South African National Parks. According to the Cape gannet breeding phenology (Crawford 2005), two main time periods were considered. (i) The breeding phase between mid-September and the end of February. The first two months of this period are spent mating and incubating, while the following 3.5 months are spent raising the chick. (ii) The non-breeding period between March and mid-September.

(a) Fishing activities

The positions of all trawls performed by commercial vessels operating in the southern Benguela in 2005 was compiled from logbooks by Marine and Coastal Management, Department of Environmental affairs and Tourism and mapped on a 20′×20′ (approx. 37×30 km) square grid. Recent investigations by Rademeyer & Butterworth (2006) showed a strong correlation between trawling effort and success in this fishing industry, hence trawling effort is a reliable index of offal production.

(b) Seabird diet

Diet data were collected monthly from Cape gannets at Malgas Island (33°03′ S, 17°55′ E) throughout 2005. Breeding and non-breeding gannets are present at the island throughout the year. Each month, an average of 37 birds (range 10–50) was caught randomly on the edge of the colony as they returned from the sea, upon which they regurgitated their stomach contents. Prey items were identified to the species level and allocated to three categories: small pelagics (anchovies and sardines); fishery wastes (more or less exclusively hake); and other prey items. Fishery waste was identified as entrails or sections of hake which would have been too large to be swallowed alive by gannets. We calculated the relative proportion of each category by mass, as well as the average calorific value of the diet for each month in 2005. To this end, we used calorific values (Batchelor & Ross 1984) of 4.07 kJ g−1 for fishery wastes, 8.59 kJ g−1 for sardines, 6.74 kJ g−1 for anchovies and 6.20 kJ g−1 for sauries (Scomberesox saurus).

(c) Seabird behaviour

Cape gannets raising large chicks were caught in January 2005 at Malgas Island where approximately 20% of their world population breeds (Crawford 2005).

Seven birds were fitted with global location sensors (GLSs; GeoLT: Earth and Ocean Technologies, Germany; 14 mm in diameter ×45 mm long, 8.2 g, approx. 0.3% of the bird's body mass) attached to a Darvic leg ring. The loggers were set to record light intensity every 30 s for up to 10 months. Light resolution was 4.5% to less than 0.025% of reading (down to approx. 0.001 lux), depending on the level. The recordings were used to estimate the position of the birds (±170 km; Phillips et al. 2004) at sunrise and sunset throughout the recording period after Wilson et al. (1992) using the software MultiTrace Geolocation (Jensen Software Systems, Laboe, Germany). Kernel analyses were subsequently performed to map the distribution of the birds. Ninety per cent concave polygons were also used under Ranges6 (Anatrack, Wareham, UK) to investigate spatial overlap between individual home ranges as well as between monthly home ranges within individual home ranges.

Fourteen birds were fitted with heart rate and depth data loggers (HRDDLs; Woakes et al. 1995), which measure 60×24×7 mm and weigh 20 g, approximately 0.7% of the bird's body mass. The HRDDLs were programmed to record depth every second and heart rate every 2 s, either continuously (seven devices) or every second day (seven devices) for up to 12 months. All devices were calibrated before and after use (depth resolution 0.1 m). Loggers were surgically implanted under isoflurane anaesthesia following Grémillet et al. (2005). Dive depth and heart rate data were analysed using the software Multitrace while discarding the first two weeks of recordings to ensure that the birds had fully recovered from the surgery. Dive depths above 0.5 m were used to extract the number of dives per day, the average maximum depth of these dives and the duration of the dives. Heart rates were analysed to determine the total time spent flying per day. Following Ropert-Coudert et al. (2006), birds were assumed to rest either on land or at the sea surface for heart rates below 220 beats min−1, and to be flying for heart rates above this threshold.

Behavioural differences between breeding and non-breeding gannets were tested using residual maximum-likelihood analyses for repeated measurements in Genstat 8th edition (VSN International Ltd, Rothamsted, UK). Effects of the time periods were determined by comparing Wald statistics (expressed as X2 throughout the results) with F-distributions (5% significance level). This method accounted for the fact that we were dealing with time series of different lengths recorded for different individuals.

(d) Seabird breeding success and energy requirements

Cape gannet breeding success at the Malgas colony was assessed for the 2004–2005 and 2005–2006 breeding seasons via monthly and bimonthly checks (at the beginning and towards the end of the season, respectively) of nests marked throughout the colony from egg-laying (September) until fledging (February of the following year). Cape gannets usually lay a single egg and raise at most one chick per year.

The average energy requirements (kJ d−1) of breeding adult Cape gannets were estimated after Ellis & Gabrielsen (2002, table 11.6) using an average body mass of 2630 g (see §3). Average energy requirements of the chick throughout the rearing period (kJ d−1) were taken from Cooper (1978).

3. Results

(a) Fishing activities

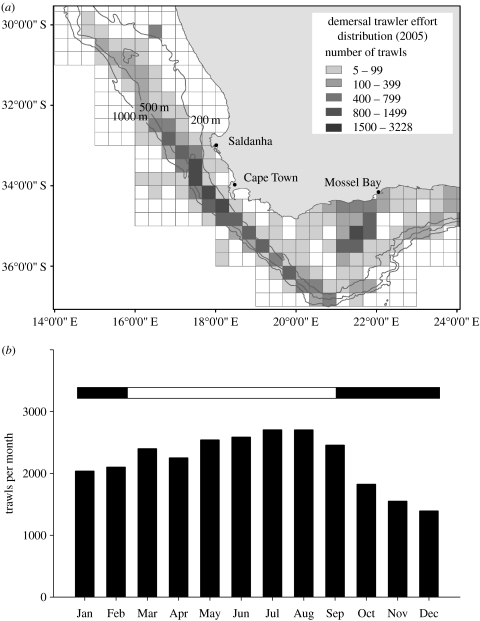

A total of 45 458 trawls were performed by commercial fishery vessels operating in the southern Benguela in 2005, out of which 26 579 occurred within the home range of Cape gannets from Malgas. Both inshore and offshore trawling fleets were primarily targeting hakes along the edge of the continental shelf and on the Agulhas Bank (south of Mossel Bay), with most effort concentrated along the shelf edge between Saldanha Bay (where the Malgas Cape gannet colony is situated) and Cape Point south of Cape Town (figure 1a). Trawling activities took place throughout the year (figure 1b), with significantly more trawls performed outside than during the gannet breeding season (2523±165 versus 1896±388 trawls per month, respectively, t=3.68, p=0.01). Trawling effort nonetheless remained extremely high throughout the year, with 45–90 trawls per day within the foraging area of Cape gannets from Malgas.

Figure 1.

(a) Distribution of commercial trawling effort in the southern Benguela in 2005 by a 20′×20′ square grid. (b) Number of trawls conducted every month in 2005 by industrial fisheries within the home range of Cape gannets from Malgas Island (2005). The horizontal bar shows the Cape gannet breeding (black) and non-breeding (white) seasons.

(b) Seabird diet

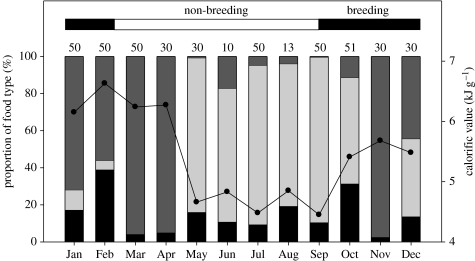

Regurgitations were obtained from 444 birds. Small pelagic fishes represented only 15% of all prey items and never comprised more than 40% for any single month (figure 2). Fishery waste represented 43% of all prey items, reaching very high proportions during the non-breeding phase (81% between May and September). There was nonetheless no significant difference in the proportion of fishery waste between the non-breeding and breeding phases (Z=1.39, p=0.2).

Figure 2.

Proportion by mass of different food types (vertical bars: black bars, small pelagics; light grey bars, fishery wastes; dark grey bars, others) in the diet of Cape gannets from Malgas Island during 2005 in relation to their breeding season (horizontal bar). Numbers at the top of the vertical bars indicate the number of birds sampled per month. Small pelagics are anchovies (E. encrasicolus) and sardines (S. sagax), and other fish species are mainly saury (S. saurus). The secondary axis and line show the monthly average calorific value of the diet.

The calculated calorific value of the diet averaged 5.43±0.77 kJ g−1 (range 4.45–6.63 kJ g−1) over the year cycle and remained lower than the calorific value of sardine (8.59 kJ g−1) and anchovy (6.74 kJ g−1) in all months (figure 2). The average calorific value of Cape gannet diet was consequently 37% lower than that for a sardine diet, and 19% lower than that for an anchovy diet.

(c) Seabird behaviour and survival

None of the chicks died immediately after deployment of the loggers on their parents. We have no information about the proportion of those chicks that fledged. However, since average breeding success was low, we suppose that many of them did not survive until the end of the breeding season. Of the 21 Cape gannets equipped with data loggers in early 2005, 18 were resighted during the following breeding season (minimum survival rate 85.7%).

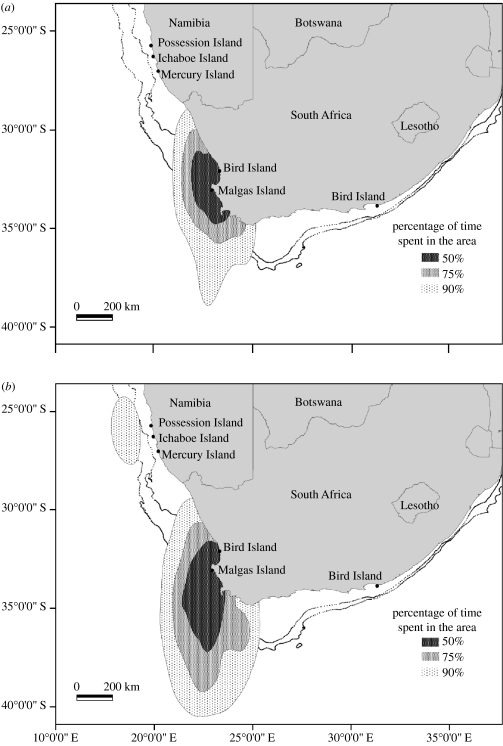

All seven GLSs were recovered. Five devices provided locations between January and November 2005 and two between January and July 2005. All seven birds remained within the Benguela year-round (figure 3a,b), with only one individual visiting the northern Benguela off the Namibian coast during the winter non-breeding period. No birds ventured into the Indian Ocean, east of Cape Agulhas (figure 3b). Half of all locations were within 300 km of the breeding colony (figure 3a,b). Month-by-month overlap analyses of maximum concave polygons revealed that (with the exception of the Namibian excursion mentioned above) individual birds remained within a well-defined area throughout the study period (average individual between-month overlap 64.8%, range 49.4–74.8%). Total home ranges of the different birds also overlapped widely (average between-bird overlap 61.3%, range 47.8–100%).

Figure 3.

Combined home ranges of seven (a) breeding and (b) non-breeding Cape gannets from Malgas Island as inferred from light levels recorded in 2005 by bird-borne GLSs (see §2 for details). Lines indicate the 500 and 1000 m isobaths.

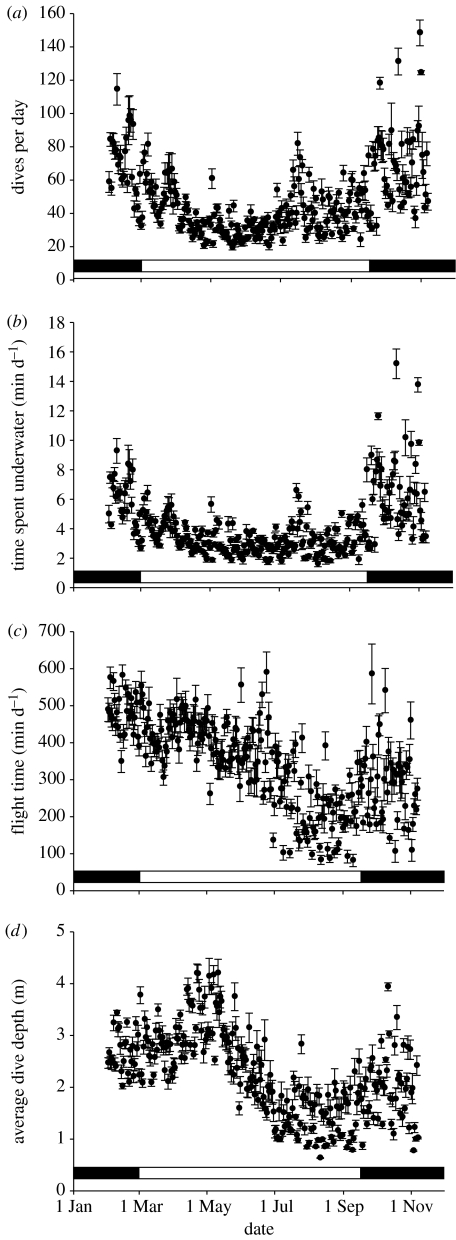

Of the 14 birds implanted with HRDDLs in January 2005, 11 were resighted while breeding in November 2005. Ten birds were caught and the HRDDL recovered. Birds showed similar body masses at the beginning and the end of the experiment (2630±100 g versus 2620±160 g, paired t-test=0.18, p=0.86). One HRDDL was faulty, five recorded throughout the study period (10 months), while the others logged data for 3, 6, 7 and 9.5 months, respectively. The behavioural parameters compiled for nine breeding and interbreeding Cape gannets showed substantial variability, but breeding birds generally worked harder than non-breeding individuals (figure 4). They performed more dives per day than non-breeding birds (69±58 versus 39±34; X2=106, p<0.001; figure 4a) and spent more time underwater (6.1±5.5 versus 3.3±2.7 min d−1; X2=99, p<0.001; figure 4b). When comparing the entire non-breeding and breeding periods, birds had similar flight times (368±281 versus 343±248 min d−1; X2=1.35, p=0.246), but between July and mid-September daily flight time fell to significantly lower levels (222±204 min d−1; X2=56, p<0.001; figure 4c). The same pattern occurred for dive depth, which was similar when comparing breeding and non-breeding phases (2.3±1.3 versus 2.3±1.6 m; X2=0.02, p=0.894), but fell to significantly lower levels between July and mid-September (1.4±1.3 m; X2=50, p<0.001; figure 4d). Only average dive duration showed no significant variability throughout the study period (5.3±1.9 s; X2=2.04, p=0.154).

Figure 4.

(a) Number of dives per day, (b) time spent underwater per day, (c) time spent flying per day and (d) average dive depth by Cape gannets between January and November 2005, showing one data point per day; values are means±s.e. (n=5–9). The horizontal bar shows breeding (black) and non-breeding (white) periods.

(d) Seabird breeding success and energy requirements

Breeding success of Cape gannets at the Malgas colony was 0.42 chicks per nest in 2004–2005 (n=55) and 0.02 chicks per nest in 2005–2006 (n=201). The latter value is the lowest ever recorded for this species, and both estimates are low compared with those from previous studies (e.g. 0.69±0.07 for the 1986–1988 time period; Navarro 1991). Such fledging success is also low compared with the average hatching success of gannets from Malgas (82%; Staverees et al. in press), indicating that breeding failure mainly occurs during the chick-rearing phase.

We estimated that breeding adult Cape gannets require an average of 3720 kJ d−1. During this period, the chick requires an average of 2060 kJ d−1. Since two parents raise one chick, each of them provides 1030 kJ d−1. Raising a chick therefore increases adult daily energy requirements by approximately 28%.

4. Discussion

Previous investigations demonstrated that fishery wastes are highly beneficial to a variety of scavenging seabirds such as albatrosses, petrels, large gulls and skuas (see reviews in Montevecchi 2002 and Furness 2003). For these species, fishery waste often has higher energy content and digestibility than their natural prey (Furness et al. 2007). Some populations consequently become dependent upon fishery wastes, to the point that a reduction in industrial fishing effort can lead to breeding failures (Oro et al. 1995). Based upon this information, we might therefore assume that abundant fishery waste is beneficial to both breeding and non-breeding Cape gannets from the Benguela. Our field data suggest that this assumption is incorrect.

In the southern Benguela, an ecosystem shift caused a drastic reduction in the availability of pelagic fishes to seabirds (Pichegru et al. 2007). Concurrently, discards from hake trawling provide substantial volumes of additional food on a year-round basis (figure 1b). As a consequence, Cape gannets which used to feed more or less exclusively on lipid-rich pelagic fishes (Crawford 2005) now take a large proportion of fishery wastes, thereby lowering the average calorific value of their diet by 19–37% (figure 2; §3)

(a) Fishery waste is beneficial to non-breeding Cape gannets

Several factors support our prediction that abundant fishery wastes are beneficial to non-breeding Cape gannets. (i) These birds did not disperse as widely as expected for non-breeding colonial birds subjected to intense intraspecific competition for food (figure 3b; Ashmole 1963). (ii) Non-breeding Cape gannets spent less time flying each day between July and September (figure 4c), indicating that they easily locate fishing vessels and meet their daily food requirements. Gannet plunge-dives were also very shallow during the last phase of the non-breeding period (figure 4d), typical of birds feeding on fishery discards. (iii) Crucially, there was a 43% reduction in the average number of dives and a 46% reduction in the average time spent underwater between the breeding and non-breeding seasons (figure 4a,b). Hence, the diving effort of non-breeding was almost half that of breeding birds, although their estimated daily energy requirements only decreased by 28%. Diving effort in Cape gannets was therefore disproportionately low during the non-breeding period, even when taking into account that they do not need to provision a chick. (iv) Such favourable conditions lead to high adult survival (at least 88%; R. Altwegg 2007, personal communication), which is in line with previous estimates for this species (Nelson 1978). Similarly, Hüppop & Wurm (2000) showed that large gulls wintering in the North Sea had better body conditions when feeding on fishery wastes than on natural prey.

(b) Fishery waste is not beneficial to breeding Cape gannets

Faced with a scarcity of pelagic fishes (Pichegru et al. 2007) and abundant fishery wastes (figure 1), breeding Cape gannets doubled their diving effort in an attempt to provide their offspring with natural prey (figure 4a). They succeeded only partly and fed their chicks (November to February) with 19% pelagic fishes, complemented by a mixture of saury and fishery wastes, thereby lowering the calorific value of their food (figure 2). The low breeding successes recorded during our study period strongly suggest that this diet was insufficient to keep chicks alive. Indeed, Batchelor & Ross (1984) showed that Cape gannet chicks fed with fishery wastes had a lower growth rate than chicks fed with sardines, which resulted in a lower probability of survival.

The beneficial influence of discards on non-breeders may or may not outweigh this lack of any beneficial effect on gannet chick growth. It nonetheless appears that fishery wastes are not necessarily beneficial to breeding seabirds such as Cape gannets. This might also be the case for other sulids such as the closely related northern gannet (Morus bassanus), which also feeds extensively on fishery wastes during late winter (Camphuysen & van der Meer 2005), but rather selects pelagic fishes when provisioning offspring (Hamer et al. 2000). More generally, it has been suggested that fast-moving avian predators such as gannets evolved digestive systems designed to process lipid-rich food quickly, yet inefficiently, while the digestive systems of scavengers (e.g. gulls) process food slowly, but efficiently (Hilton et al. 2000). This might explain why gannets are less capable than gulls of breeding successfully when feeding on low-energy fishery wastes.

In conclusion, our study demonstrates the relevance of the JFH for Cape gannets feeding on fishery wastes. These findings are consistent with numerous previous studies, which show that animals raising young have to provision their offspring with high-quality diet in order to ensure growth, and that this diet is usually different from their own (Barclay 1994; Davoren & Burger 1999; Österblom et al. 2001). Overall, our study shows that fishery wastes may not necessarily rescue marine top-predators facing shortages of their natural prey. Therefore, marine management policies should not assume that fishery waste is generally beneficial to scavenging seabirds and that abundance of this artificial resource will automatically inflate seabird populations.

Acknowledgments

All work on Cape gannets complies with South African ethics standards and was performed under permits of South African National Parks.

This study was funded via an ACI Jeunes Chercheuses et Jeunes Chercheurs from CNRS to D.G. and by a studentship of the French Ministry of Research to L.P. We thank Ralf Mullers for his help in the field, Bénédicte Martin for analysing the gannet dive data, University of Cape Town and Marine and Coastal Management for logistic support, and two anonymous referees for their very constructive comments.

References

- Abrams R.W. Pelagic seabirds and trawl-fisheries in the southern Benguela current region. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 1983;11:151–156. doi:10.3354/meps011151 [Google Scholar]

- Ashmole N.P. The regulation of numbers of tropical oceanic birds. Ibis. 1963;103:458–473. [Google Scholar]

- Barclay R.M. Constraints on reproduction by flying vertebrates—energy and calcium. Am. Nat. 1994;144:1021–1031. doi:10.1086/285723 [Google Scholar]

- Batchelor A.L, Ross G.J.B. The diet and implications of dietary change of Cape gannets on Bird Island, Nelson Mandela Bay. Ostrich. 1984;55:45–63. [Google Scholar]

- Camphuysen C.J, van der Meer J. Wintering seabirds in west Africa: foraging hotspots off western Sahara and Mauritania driven by upwelling and fisheries. Afr. J. Mar. Sci. 2005;27:427–437. [Google Scholar]

- Catchpole T.L, Frid C.L.J, Gray T.S. Importance of discards from the English Nephrops norvegicus fishery in the North Sea to marine scavengers. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2006;313:215–226. doi:10.3354/meps313215 [Google Scholar]

- Cooper J. Energetic requirements for growth and maintenance of the Cape gannet (Aves; Sulidae) Zoologica Africana. 1978;13:305–317. [Google Scholar]

- Crawford, R. J. M. 2005 Cape gannet. In Robert's birds of southern Africa (eds P. A. R. Hockey, W. R. J. Dean & P. G. Ryan), pp. 575–577, VIIth edn. Cape Town, Republic of South Africa: John Voelcker Bird Book Fund.

- Davoren G.K, Burger A.E. Differences in prey selection and behaviour during self-feeding and chick provisioning in rhinoceros auklets. Anim. Behav. 1999;58:853–863. doi: 10.1006/anbe.1999.1209. doi:10.1006/anbe.1999.1209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis H.I, Gabrielsen G.W. Energetic of free-ranging seabirds. In: Schreiber E.A, Burger J, editors. Biology of marine birds. CRC Press; Boca Raton, FL: 2002. pp. 359–407. [Google Scholar]

- Furness R.W. Impacts of fisheries on seabird communities. Sci. Mar. 2003;67:33–45. [Google Scholar]

- Furness R.W, Edwards A.E, Oro D. Influence of management practices and of scavenging seabirds on availability of fisheries discards to benthic scavengers. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2007;350:235–244. doi:10.3354/meps07191 [Google Scholar]

- Garthe S, Hüppop O. Distribution of ship-following seabirds and their utilisation of discards in the North-Sea in summer. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 1994;106:1–9. doi:10.3354/meps106001 [Google Scholar]

- Garthe S, Camphuysen K.C.J, Furness R.W. Amounts of discards by commercial fisheries and their significance as food for seabirds in the North Sea. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 1996;136:1–11. doi:10.3354/meps136001 [Google Scholar]

- Grémillet D, Kuntz G, Woakes A.J, Gilbert C, Robin J.-P, Le Maho Y, Butler P.J. Year-round recordings of behavioural and physiological parameters reveal the survival strategy of a poorly insulated diving endotherm during the Arctic winter. J. Exp. Biol. 2005;208:4231–4241. doi: 10.1242/jeb.01884. doi:10.1242/jeb.01884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths C.L, et al. Impacts of human activities on marine life in the Benguela: a historical overview. Oceanogr. Mar. Biol. Annu. Rev. 2004;42:303–392. [Google Scholar]

- Hamer K.C, Phillips R.A, Wanless S, Harris M.P, Wood A.G. Foraging ranges, diets and feeding locations of gannets Morus bassanus in the North Sea: evidence from satellite telemetry. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2000;200:257–264. doi:10.3354/meps200257 [Google Scholar]

- Hilton G.M, Ruxton G.D, Furness R.W, Houston D.C. Optimal digestion strategies in seabirds: a modeling approach. Evol. Ecol. Res. 2000;2:207–230. [Google Scholar]

- Hüppop O, Wurm S. Effects of winter fishery activities on resting numbers, food and body condition of large gulls Larus argentatus and L-marinus in the south-eastern North Sea. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2000;194:241–247. doi:10.3354/meps194241 [Google Scholar]

- Jennings S, Kaiser M.J, Reynolds J.D. Blackwell Publishing; Oxford, UK: 2001. Marine fisheries ecology. [Google Scholar]

- Jodice P.G.R, et al. Assessing the nutritional stress hypothesis: relative influence of diet quantity and quality on seabird productivity. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2006;325:267–279. doi:10.3354/meps325267 [Google Scholar]

- Kelleher, K. 2005 Discards in the world's marine fisheries: an update. FAO fisheries technical paper, no. 470. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome, Italy.

- Kitaysky A.S, Kitaiskaia E.V, Piatt J.F, Wingfield J.C. A mechanistic link between chick diet and decline in seabirds? Proc. R. Soc. B. 2005;273:445–450. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2005.3351. doi:10.1098/rspb.2005.3351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litzow M.A, Piatt J.F, Prichard A.K, Roby D.D. Response of pigeon guillemots to variable abundance of high-lipid and low-lipid prey. Oecologia. 2002;132:286–295. doi: 10.1007/s00442-002-0945-1. doi:10.1007/s00442-002-0945-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montevecchi W.A. Interactions between fisheries and seabirds. In: Schreiber E.A, Burger J, editors. Biology of marine birds. CRC Press; Boca Raton, FL: 2002. pp. 527–557. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro R.A. Food addition and twinning experiments in the Cape gannet: effects on breeding success and chick growth and behaviour. Colon. Waterbirds. 1991;14:92–102. doi:10.2307/1521496 [Google Scholar]

- Nelson J.B. Oxford University Press; Oxford, UK: 1978. The sulidae: gannets and boobies. [Google Scholar]

- Oro D, Bosch M, Ruiz X. Effects of a trawling moratorium on the breeding success of the yellow-legged gull Larus cachinnans. Ibis. 1995;137:547–549. [Google Scholar]

- Österblom H, Bignert A, Fransson T, Olsson O. A decrease in fledging body mass in common guillemot Uria aalge chicks in the Baltic Sea. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2001;224:305–309. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips R.A, Silk J.R.D, Croxall J.P, Afanasyev V, Briggs D.R. Accuracy of geolocation estimates for flying seabirds. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2004;266:265–272. doi:10.3354/meps266265 [Google Scholar]

- Piatt, J. F., Anderson, P. 1996 Response of common murres to the Exxon Valdez oil spill in the Gulf of Alaska Marine Ecosystem. In Exxon Valdez Oil Spill Symposium Proceedings, vol. 18 (eds S. D. Rice, R. B. Spies, D. A. Wolfe, B. A. Wright). American Fisheries Society Symposium, pp. 712–719. Bethesda, MD: American fisheries Society.

- Pichegru L, Ryan P, van der Lingen C.D, Coetzee J, Ropert-Coudert Y, Grémillet D. Foraging behaviour and energetics of Cape gannets Morus capensis feeding on live prey and fishery discards in the Benguela upwelling system. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2007;350:127–136. doi:10.3354/meps07128 [Google Scholar]

- Rademeyer, R. A. & Butterworth D. S. 2006 Updated reference set for the South African Merluccius paradoxus and M. capensis resources and projections under a series of candidate OMPs marine and coastal management, Republic of South Africa internal report WG/09/06/D:H:33, pp. 1–27.Cape Town, Republic of South Africa: Marine and Coastal Management.

- Ropert-Coudert Y, Wilson R.P, Grémillet D, Kato A, Lewis S, Ryan P.G. ECG Recordings in free-ranging gannets reveal minimum difference in heart rate during powered versus gliding flight. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2006;328:275–284. doi:10.3354/meps328275 [Google Scholar]

- Rosen D.A.S, Trites A.W. Digestive efficiency and dry-matter digestibility in Steller sea lions fed herring, pollock, squid, and salmon. Can. J. Zool. 2000;78:234–239. doi:10.1139/cjz-78-2-234 [Google Scholar]

- Ryan P.G, Moloney C.L. Effect of trawling on bird and seal distribution in the southern Benguela region. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 1988;45:1–11. doi:10.3354/meps045001 [Google Scholar]

- Shannon L.V. The Benguela ecosystem. Part I. Evolution of the Benguela, physical features and processes. Oceanogr. Mar. Biol. Annu. Rev. 1985;23:105–183. [Google Scholar]

- Staverees, L., Crawford, R. J. M. & Underhill L. G. In press. Factors influencing the breeding success of Cape gannets Morus capensis at Malgas Island 2002–2003. Ostrich

- Tasker M.L, Camphuysen C.J.K, Cooper J, Garthe S, Montevecchi W.A, Blaber S.J.M. The impacts of fishing on marine birds. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2000;57:531–547. doi:10.1006/jmsc.2000.0714 [Google Scholar]

- Votier S.C, et al. Changing fisheries discard rates and seabird communities. Nature. 2004;427:727–730. doi: 10.1038/nature02315. doi:10.1038/nature02315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walmsley S.A, Leslie R.W, Sauer W.H.H. Managing South Africa's trawl bycatch. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2007;64:405–412. doi:10.1093/icesjms/fsl022 [Google Scholar]

- Wanless S, Harris M.P, Redman P, Speakman J.R. Low energy value of fish as a probable cause of a major seabird breeding failure in the North Sea. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2005;294:1–8. doi:10.3354/meps294001 [Google Scholar]

- Wilson R.P, Duchamp J.J, Rees W.G, Culik B.M, Niekamp K. Estimation of location: global coverage using light intensity. In: Priede I.M, Swift S.M, editors. Wildlife telemetry: remote monitoring and tracking of animals. Ellis Howard; Chichester, UK: 1992. pp. 131–134. [Google Scholar]

- Woakes A.J, Butler P.J, Bevan R.M. Implantable data logging system for the heart rate and body temperature: its application to the estimation of field metabolic rates in Antarctic predators. Med. Biol. Eng. Comput. 1995;33:145–151. doi: 10.1007/BF02523032. doi:10.1007/BF02523032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]