Abstract

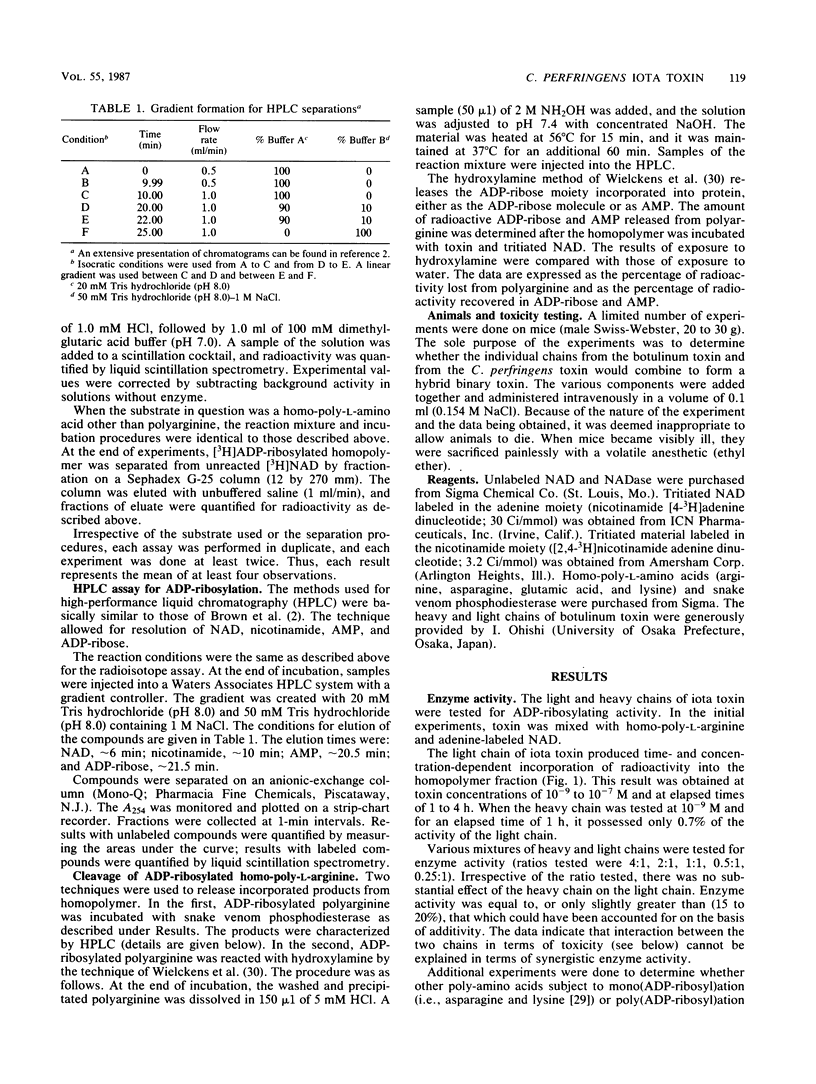

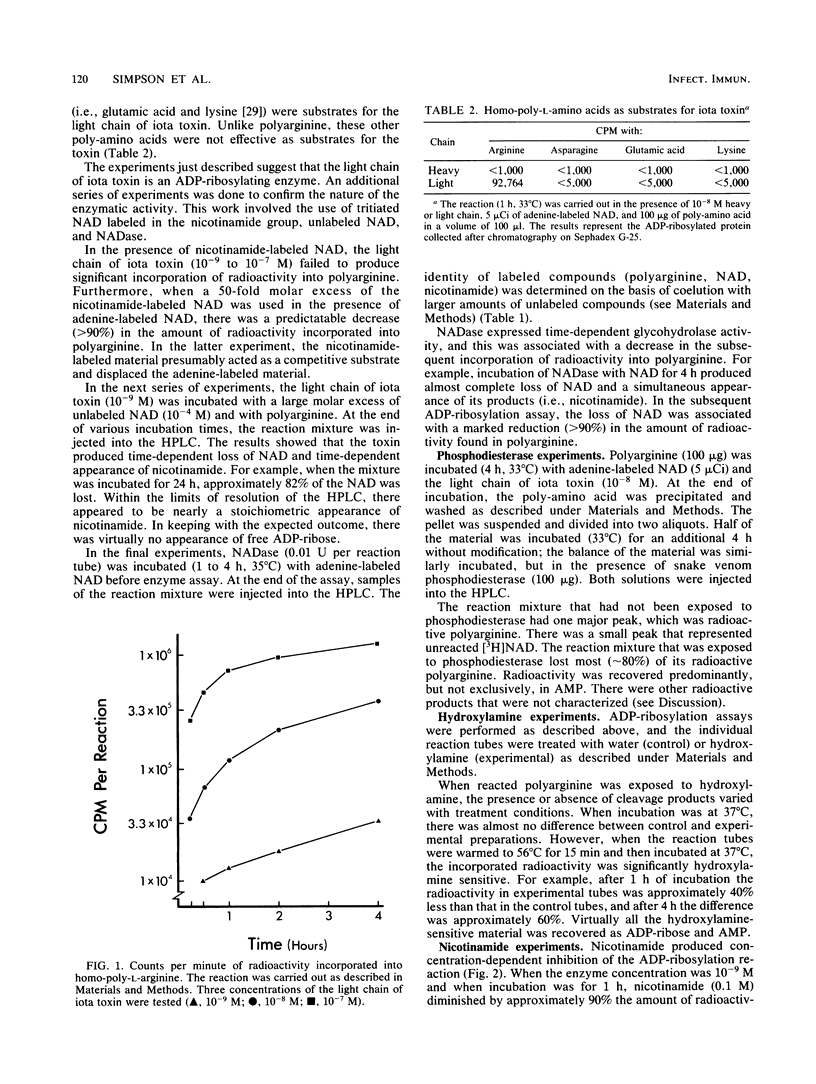

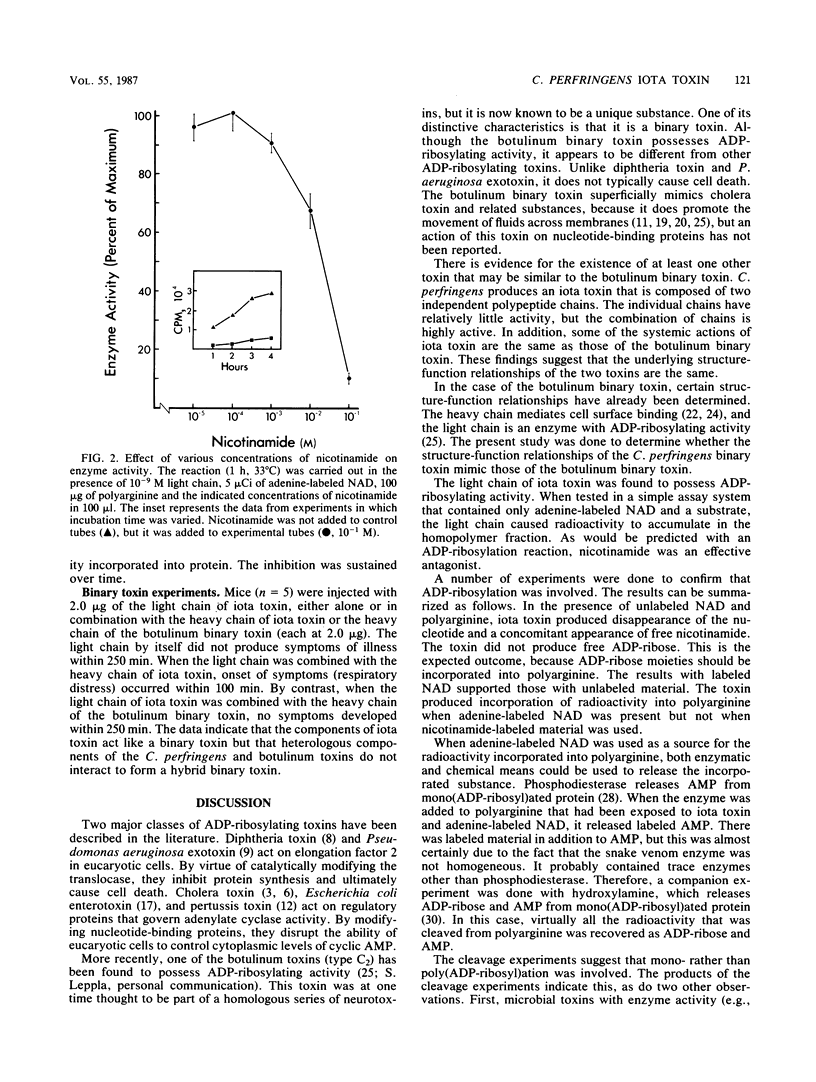

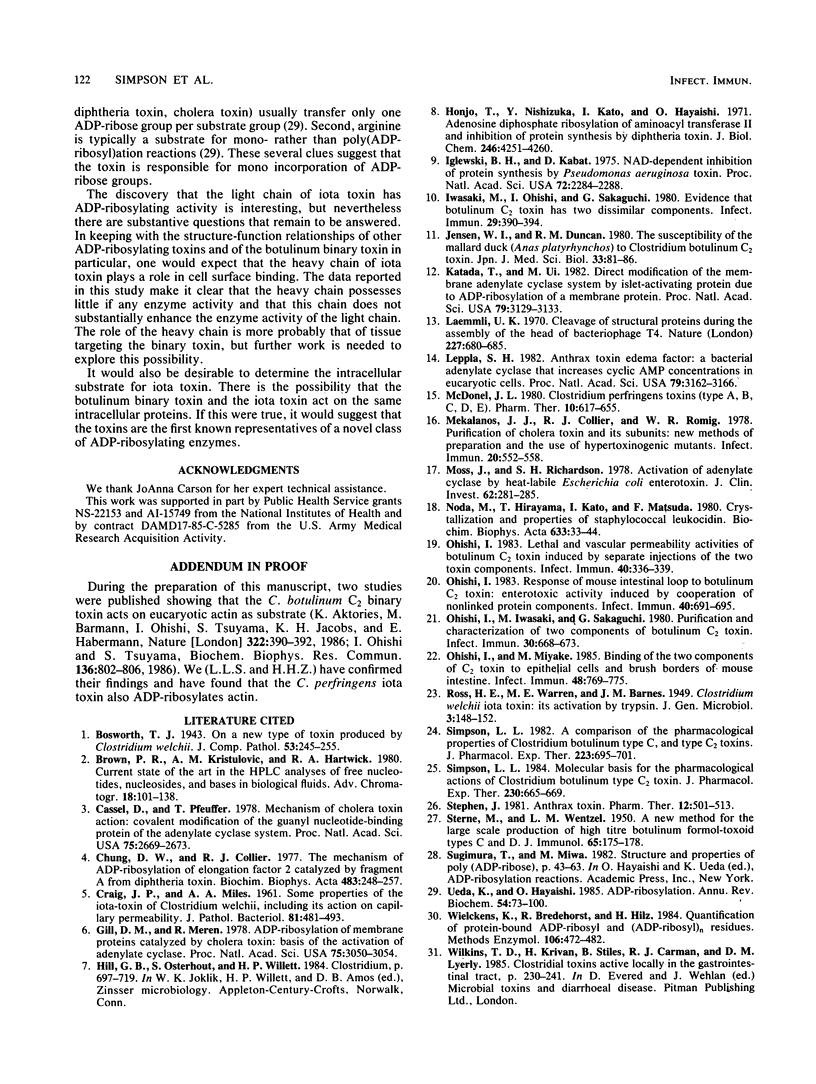

Clostridium perfringens type E iota toxin is composed of two separate and independent polypeptide chains that act synergistically in mouse lethal assays. The light chain is an enzyme that mono(ADP-ribosyl)ates certain amino acids. The enzyme displays substantial activity when homopoly-L-arginine is used as a substrate, but it shows little activity when polyasparagine, polylysine or polyglutamic acid are used. In keeping with the properties of an ADP-ribosylating enzyme, the toxin possesses the following characteristics. It produces incorporation of radioactivity into polyarginine when adenine-labeled NAD is used, but radioactivity is not incorporated when nicotinamide-labeled NAD is used. Irrespective of labeling, enzymatic activity is accompanied by the release of free nicotinamide. After incorporation of ADP-ribose groups into polyarginine, enzymatic and chemical techniques can be used to release the incorporated material. Snake venom phosphodiesterase releases mainly AMP; hydroxylamine releases AMP and ADP-ribose. The heavy chain of iota toxin has little or no enzyme activity, and it does not substantially affect the enzyme activity of the light chain. The heavy chain may be a binding component that directs the toxin to vulnerable cells. The data suggest that iota toxin is a representative of a novel class of ADP-ribosylating toxins.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Aktories K., Bärmann M., Ohishi I., Tsuyama S., Jakobs K. H., Habermann E. Botulinum C2 toxin ADP-ribosylates actin. Nature. 1986 Jul 24;322(6077):390–392. doi: 10.1038/322390a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown P. R., Krstulovic A. M., Hartwick R. A. Current state of the art in the HPLC analyses of free nucleotides, nucleosides, and bases in biological fluids. Adv Chromatogr. 1980;18:101–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CRAIG J. P., MILES A. A. Some properties of the iota-toxin of Clostridium welchii, including its action on capillary permeability. J Pathol Bacteriol. 1961 Apr;81:481–493. doi: 10.1002/path.1700810221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassel D., Pfeuffer T. Mechanism of cholera toxin action: covalent modification of the guanyl nucleotide-binding protein of the adenylate cyclase system. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1978 Jun;75(6):2669–2673. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.6.2669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung D. W., Collier R. J. The mechanism of ADP-ribosylation of elongation factor 2 catalyzed by fragment A from diphtheria toxin. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1977 Aug 11;483(2):248–257. doi: 10.1016/0005-2744(77)90053-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill D. M., Meren R. ADP-ribosylation of membrane proteins catalyzed by cholera toxin: basis of the activation of adenylate cyclase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1978 Jul;75(7):3050–3054. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.7.3050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honjo T., Nishizuka Y., Kato I., Hayaishi O. Adenosine diphosphate ribosylation of aminoacyl transferase II and inhibition of protein synthesis by diphtheria toxin. J Biol Chem. 1971 Jul 10;246(13):4251–4260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iglewski B. H., Kabat D. NAD-dependent inhibition of protein synthesis by Pseudomonas aeruginosa toxin,. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1975 Jun;72(6):2284–2288. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.6.2284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwasaki M., Ohishi I., Sakaguchi G. Evidence that botulinum C2 toxin has two dissimilar components. Infect Immun. 1980 Aug;29(2):390–394. doi: 10.1128/iai.29.2.390-394.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen W. I., Duncan R. M. The susceptibility of the mallard duck (Anas platyrhynchos) to Clostridium botulinum C2 toxin. Jpn J Med Sci Biol. 1980 Apr;33(2):81–86. doi: 10.7883/yoken1952.33.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katada T., Ui M. Direct modification of the membrane adenylate cyclase system by islet-activating protein due to ADP-ribosylation of a membrane protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1982 May;79(10):3129–3133. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.10.3129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli U. K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970 Aug 15;227(5259):680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leppla S. H. Anthrax toxin edema factor: a bacterial adenylate cyclase that increases cyclic AMP concentrations of eukaryotic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1982 May;79(10):3162–3166. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.10.3162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonel J. L. Clostridium perfringens toxins (type A, B, C, D, E). Pharmacol Ther. 1980;10(3):617–655. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(80)90031-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mekalanos J. J., Collier R. J., Romig W. R. Purification of cholera toxin and its subunits: new methods of preparation and the use of hypertoxinogenic mutants. Infect Immun. 1978 May;20(2):552–558. doi: 10.1128/iai.20.2.552-558.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss J., Richardson S. H. Activation of adenylate cyclase by heat-labile Escherichia coli enterotoxin. Evidence for ADP-ribosyltransferase activity similar to that of choleragen. J Clin Invest. 1978 Aug;62(2):281–285. doi: 10.1172/JCI109127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noda M., Hirayama T., Kato I., Matsuda F. Crystallization and properties of staphylococcal leukocidin. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1980 Nov 17;633(1):33–44. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(80)90035-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohishi I., Iwasaki M., Sakaguchi G. Purification and characterization of two components of botulinum C2 toxin. Infect Immun. 1980 Dec;30(3):668–673. doi: 10.1128/iai.30.3.668-673.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohishi I. Lethal and vascular permeability activities of botulinum C2 toxin induced by separate injections of the two toxin components. Infect Immun. 1983 Apr;40(1):336–339. doi: 10.1128/iai.40.1.336-339.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohishi I., Miyake M. Binding of the two components of C2 toxin to epithelial cells and brush borders of mouse intestine. Infect Immun. 1985 Jun;48(3):769–775. doi: 10.1128/iai.48.3.769-775.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohishi I. Response of mouse intestinal loop to botulinum C2 toxin: enterotoxic activity induced by cooperation of nonlinked protein components. Infect Immun. 1983 May;40(2):691–695. doi: 10.1128/iai.40.2.691-695.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohishi I., Tsuyama S. ADP-ribosylation of nonmuscle actin with component I of C2 toxin. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1986 Apr 29;136(2):802–806. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(86)90511-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STERNE M., WENTZEL L. M. A new method for the large-scale production of high-titre botulinum formol-toxoid types C and D. J Immunol. 1950 Aug;65(2):175–183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson L. L. A comparison of the pharmacological properties of Clostridium botulinum type C1 and C2 toxins. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1982 Dec;223(3):695–701. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson L. L. Molecular basis for the pharmacological actions of Clostridium botulinum type C2 toxin. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1984 Sep;230(3):665–669. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephen J. Anthrax toxin. Pharmacol Ther. 1981;12(3):501–513. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(81)90095-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueda K., Hayaishi O. ADP-ribosylation. Annu Rev Biochem. 1985;54:73–100. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.54.070185.000445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wielckens K., Bredehorst R., Hilz H. Quantification of protein-bound ADP-ribosyl and (ADP-ribosyl)n residues. Methods Enzymol. 1984;106:472–482. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(84)06051-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkins T., Krivan H., Stiles B., Carman R., Lyerly D. Clostridial toxins active locally in the gastrointestinal tract. Ciba Found Symp. 1985;112:230–241. doi: 10.1002/9780470720936.ch13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]