Abstract

Mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization and the release of intermembrane space proteins, such as cytochrome c, are early events during intrinsic (mitochondria-mediated) apoptotic signaling. Although this process is generally accepted to require the activation of Bak or Bax, the underlying mechanism responsible for their activation during true intrinsic apoptosis is not well understood. In the current study, we investigated the molecular requirements necessary for Bak activation using distinct clones of Bax-deficient Jurkat T-lymphocytes in which the intrinsic pathway had been inhibited. Cells stably overexpressing Bcl-2/Bcl-xL or stably depleted of Apaf-1 were equally resistant to apoptosis induced by the DNA-damaging anticancer drug etoposide as determined by phosphatidylserine externalization and caspase activation. Strikingly, characterization of mitochondrial apoptotic events in all three drug-resistant cell lines revealed that, without exception, resistance to apoptosis was associated with an absence of Bak activation, cytochrome c release, and mitochondrial membrane depolarization. Furthermore, we found that etoposide-induced apoptosis and mitochondrial events were inhibited in cells stably overexpressing either full-length X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein (XIAP) or the BIR1/BIR2 domains of XIAP. Combined, our findings suggest that caspase-mediated positive amplification of initial mitochondrial changes can determine the threshold for irreversible activation of the intrinsic apoptotic pathway.

Apoptosis is a gene-regulated form of cell death that is critical for normal development and tissue homeostasis. Disruptions in the control of apoptosis can contribute to the onset of various pathological states including cancer, where avoidance of apoptosis confers a survival advantage to tumorigenic cells. Apoptosis is mediated by a family of cysteine proteases that cleave after aspartate residues (caspases) and can be activated by two distinct signaling pathways.

The intrinsic (mitochondria-mediated) pathway is activated by cytotoxic stressors, such as DNA damage, γ-radiation, growth factor withdrawal, and heat. Such stimuli are known to cause mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization (MOMP)2 and stimulate the release of cytochrome c, second mitochondria-derived activator of caspase (Smac, also known as DIABLO), and Omi (also known as HtrA2) into the cytosol, where they work together to activate the initiator procaspase-9 within the apoptotic protease-activating factor-1 (Apaf-1) apoptosome complex (1). Once activated, caspase-9 activates effector procaspase-3 or -7, which, in turn, can cleave various protein substrates, leading to the morphological and biochemical features of apoptosis.

The process of MOMP is generally thought to require the activation of a multidomain Bcl-2 family protein, notably Bax or Bak (2, 3). Cells deficient in either Bax or Bak display relatively minor defects in apoptosis, whereas doubly deficient cells are often found to be highly resistant to mitochondria-mediated apoptosis induced by a variety of stimuli (4, 5). Normally, these proteins exist as inactive monomers either in the cytosol (Bax) or associated with the mitochondria (Bak). Activation of Bax and Bak coincides with their homo-oligomerization, which is thought to occur by one of two mechanisms. One model argues for the existence of “sensitizer” Bcl-2 homology 3 (BH3)-only proteins, such as Noxa and Bad, that can displace “activator” BH3-only Bcl-2 family proteins, such as Bim, truncated Bid (tBid), and Puma, from a prosurvival protein, such as Bcl-2 or Bcl-xL, to activate Bak or Bax (6). The second model indicates that BH3-only proteins bind and neutralize prosurvival Bcl-2 proteins that normally keep Bak or Bax inactive (7, 8). A well characterized example of Bak or Bax activation being induced by a BH3-only protein is during receptor-mediated apoptosis in so-called type II cells. In this case, death receptor ligation activates caspase-8, which, in turn, cleaves the cytosolic BH3-only protein Bid to tBid (9, 10), resulting in the direct or indirect activation of Bak or Bax. A similar emergent understanding of a mechanism responsible for the activation of Bak/Bax during true mitochondria-mediated apoptosis is currently lacking.

In this regard, the aim of the current study was to investigate the signaling requirements for MOMP during intrinsic apoptosis, as well as to help define the elusive threshold a cell must cross in order to be irreversibly committed to undergo this form of cell death. We have engineered several clones of Bax-deficient Jurkat cells in which the intrinsic pathway is inhibited due to the stable overexpression of Bcl-2 or Bcl-xL, the stable knockdown of Apaf-1, or the overexpression of full-length XIAP or the baculoviral inhibitor of apoptosis protein repeat 1 and 2 (BIR1/BIR2) domains of XIAP. The results indicated that all five of the gene-manipulated Jurkat cell lines were similarly resistant to etoposide-induced apoptosis. As anticipated, Bcl-2/Bcl-xL-overexpressing cells were refractory to all etoposide-induced mitochondrial events. Strikingly, however, Apaf-1-silenced cells and cells overexpressing full-length XIAP or the BIR1/BIR2 domains of XIAP were also found to be impaired in their ability to activate Bak, release cytochrome c, or lose mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψ) in response to etoposide.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Culture—Wild-type Jurkat T-lymphocytes (clone E6.1) were cultured in RPMI 1640 complete medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% (v/v) heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (HyClone, Logan, UT), 2% (w/v) glutamine, 100 units/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin at 37 °C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator. For transfected Jurkat cells, 1 mg/ml Geneticin (Invitrogen) was substituted for penicillin and streptomycin. Cells were maintained in an exponential growth phase for all experiments. All cells were replated in fresh complete non-selective medium prior to apoptosis induction. Apoptosis was induced with etoposide (10 μm; Sigma).

Transfections—Wild-type Jurkat T-lymphocytes (107) were transfected with 20 μg of plasmid DNA (pSFFV-Bcl-2, pSFFV-Bcl-xL, pSFFV-neo, pSUPER-Apaf-1, pSUPER-neo, pcDNA3-XIAP, pcDNA3-XIAP-BIR1/BIR2, or pcDNA3-neo) by electroporation using a Bio-Rad Gene Pulser Xcell system (0.4-cm cuvette, 300 V and 950 microfarads). Cells were allowed to recover in RPMI 1640 complete medium for 48 h at 37 °C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator. Selection of transfected cells was performed in the presence of 1 mg/ml Geneticin for several weeks, at which time serial dilutions were performed to obtain single-cell clones of Bcl-2- and Bcl-xL-overexpressing cells, Apaf-1-silenced cells, and cells overexpressing full-length XIAP or the BIR1/BIR2 domains of XIAP.

Flow Cytometry for Cell Death and Mitochondrial Membrane Potential (ΔΨ) Measurements—Phosphatidylserine exposure on the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane was detected using the annexin V-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) Apoptosis Detection Kit II (Pharmingen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. In brief, 106 cells were pelleted following etoposide treatment and washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Next, the cells were resuspended in 100 μl of binding buffer containing annexin V-FITC and propidium iodide. Prior to flow cytometric analysis, 400 μl of binding buffer were added to the cells. For ΔΨ determination, the MitoProbe DiIC1(5) Kit (Invitrogen) was used. Briefly, cells (106) were pelleted following drug treatment, washed once in PBS, and resuspended in 1 ml of warm PBS. Next, 5 μl of 10 μm DiIC1(5) were added to the cells and incubated in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator at 37 °C for 15 min. Cells were pelleted, resuspended in 500 μl of PBS, and analyzed by flow cytometry.

Western Blotting—Pelleted cells (5 × 106) were resuspended and lysed in 200 μl of ice-cold lysis buffer (10 mm Tris/HCl, pH 7.4, 10 mm NaCl, 3 mm MgCl2, 1 mm EDTA, 0.1% Nonidet P-40) supplemented with a mixture of protease inhibitors (Complete Mini EDTA-Free, Roche Applied Science). Protein concentrations were determined using the bicinchoninic acid assay (Pierce) and equal amounts were mixed with Laemmli. Western blot analysis was carried out as described previously (11). The antibodies used were mouse anti-Apaf-1 (clone 94408, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), rabbit anti-Bax (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), rabbit anti-Bak NT (Millipore), mouse anti-Bcl-2 (DakoCytomation, Glostrup, Denmark), rabbit anti-Bcl-xL (clone 54H6, Cell Signaling), mouse anti-β-actin (clone AC-15, Sigma), rabbit anti-Bid (Cell Signaling), rabbit anti-caspase-3 (clone 8G10, Cell Signaling), rabbit anti-caspase-6 (Cell Signaling), rabbit anti-caspase-7 (Cell Signaling), mouse anti-caspase-8 (clone 1C12, Cell Signaling), rabbit anti-caspase-9 (Cell Signaling), mouse anti-cytochrome c (clone 7H8.2C12, Pharmingen), rabbit anti-glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (Trevigen, Gaithersburg, MD), mouse anti-Myc (clone 9E10, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), mouse anti-Smac/DIABLO (Cell Signaling), and mouse anti-XIAP (clone 28, BD Transduction Laboratories).

Subcellular Fractionation—Cells (106) were washed in PBS, resuspended in 50 μl of buffer (140 mm mannitol, 46 mm sucrose, 50 mm KCl, 1 mm KH2PO4, 5 mm MgCl2, 1 mm EGTA, 5 mm Tris, pH 7.4) supplemented with a mixture of protease inhibitors (Complete Mini-EDTA Free), and permeabilized with 3 μg of digitonin (Sigma) on ice for 10 min. Plasma membrane permeabilization was monitored by trypan blue staining, and cell suspensions were centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. Supernatant and pellet fractions were subjected to Western blot analysis.

Determination of Bak Oligomerization and Activation—For detection of Bak oligomerization, cells (106) were harvested, washed and resuspended in 80 μl of 100 mm EDTA/PBS, incubated with the cross-linking agent bismaleimidohexane (1 mm) for 30 min at room temperature (22 °C), quenched with 100 mm dithiothreitol for 15 min, pelleted, and processed for Western blotting. For detection of activated Bak by flow cytometry, cells (106) were washed in PBS, fixed in 400 μl of 0.25% paraformaldehyde for 5 min, subsequently washed two times with 1% fetal bovine serum in PBS, and incubated in 50 μl of staining buffer (1% fetal bovine serum and 100 μg/ml digitonin in PBS) with a conformation-specific mouse monoclonal antibody against Bak (1:30; AM03, Calbiochem) for 30 min at room temperature (22 °C). Then, cells were washed and resuspended in 50 μlof staining buffer containing 0.25 μg of Alexa Fluor 488-labeled chicken anti-mouse antibody for 30 min in the dark. Cells were washed again and analyzed by flow cytometry. Analysis and histogram overlays were performed using FlowJo software (Tree Star, Ashland, OR).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Blockade of the Intrinsic Pathway by Depleting Apaf-1 or Overexpressing Bcl-2/Bcl-xL Completely Inhibits Etoposide-induced Apoptosis in Jurkat Cells—The largest body of evidence indicates that MOMP and the release of intermembrane space proteins, such as cytochrome c, involves the activation of multidomain pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins Bak and Bax (2, 3). Although it is clear that active caspase-8 within the extrinsic apoptotic pathway can activate Bak or Bax by cleaving the BH3-only protein Bid to tBid (9, 10, 12), a similar prominent role for one or more caspases in modulating MOMP during true intrinsic apoptosis is not appreciated. In some instances, incubation of cells with the topoisomerase II inhibitor etoposide was found to induce caspase-8-mediated cleavage of Bid by stimulating an up-regulation of Fas ligand that, in turn, activated the Fas receptor (13–15). However, other studies, including our own unpublished results3, have shown that caspase-8-deficient cells are sensitive to etoposide-induced apoptosis (16). Other evidence has suggested that caspase-2 may be able to activate Bax by first cleaving Bid in response to stress (17–20), although it was also shown that Bid is a relatively poor substrate for caspase-2 (18, 19). In addition, we recently demonstrated that Apaf-1 is required for etoposide-induced activation of all caspases, suggesting that most, if not all, caspase activation occurs downstream of apoptosome formation (21).

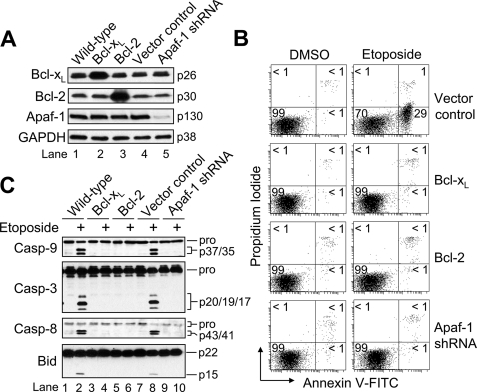

To investigate the molecular requirements for etoposide-induced MOMP, we initially used the same Apaf-1-deficient Jurkat cells described previously (Fig. 1A, lane 5) (21), as well as cells in which the intrinsic pathway had been inhibited due to the overexpression of either Bcl-xL or Bcl-2 (lanes 2 and 3). As illustrated in Fig. 1A, manipulating the level of expression of Apaf-1, Bcl-2, or Bcl-xL did not result in any alteration in the expression of the other two proteins. According to Fig. 1B, control-transfected Jurkat cells were induced to undergo apoptosis (∼30%), as determined by annexin V-FITC labeling of externalized phosphatidylserine on the plasma membrane, when incubated in the presence of a clinically relevant concentration of etoposide (10 μm) for 6 h. By comparison, Jurkat cells in which either Apaf-1 expression had been silenced or an anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family protein had been overexpressed were totally protected from etoposide-induced apoptosis (Fig. 1B). In agreement with these findings, Western blot analysis of cell lysates obtained at 6 h post-etoposide treatment revealed that proteolytic processing of procaspase-8, -9, and -3 occurred in wild-type and control-transfected cells, but not in any of the three gene-manipulated clones (Fig. 1C). In addition, cleavage of Bid to tBid was observed only in etoposide-treated wild type and vector control cells, suggesting that Bid cleavage occurs downstream of the apoptosome. Taken together, these data clearly demonstrate that silencing Apaf-1 or overexpressing Bcl-2/Bcl-xL results in a total blockade of the intrinsic pathway in Jurkat cells.

FIGURE 1.

Inhibiting the intrinsic pathway by Bcl-2/Bcl-xL overexpression or Apaf-1 knockdown blocks etoposide-induced apoptosis in Jurkat cells. A, wild-type, control-transfected, Bcl-xL- and Bcl-2-overexpressing, and Apaf-1-deficient Jurkat clones were harvested and lysed for Western blotting. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as a loading control. B, cells (106/ml) were cultured with DMSO or 10 μm etoposide for 6 h and processed for cell death determination by flow cytometric analysis of annexin V-FITC and propidium iodide staining. Quadrants are defined as live (lower left), early apoptotic (lower right), late apoptotic (upper right), and necrotic (upper left). Numbers refer to the percentage of cells in each quadrant. C, duplicate aliquots of cells in B were harvested and lysed for Western blotting. shRNA, short hairpin RNA; Casp, caspase.

Bak Activation Is Impaired in Apaf-1-deficient Cells Treated with Etoposide—In many settings, cytochrome c release is a rapid, complete, and irreversible event that represents the “point of no return” within the intrinsic apoptotic pathway (22). In addition, it is generally accepted that caspase-9 activation requires cytochrome c-mediated oligomerization of Apaf-1 and that cytochrome c release occurs independently of downstream caspase activity (1, 23, 24). In this regard, cells deficient in Apaf-1, caspase-9, or executioner caspases-3 and -7 would be expected to undergo MOMP and release intermembrane space proteins with the same kinetics as wild-type cells. However, some evidence is at odds with such a view of the intrinsic pathway. For instance, it has been shown that procaspases can be activated by a cytochrome c- and apoptosome-independent, but Apaf-1-dependent, mechanism in thymocytes exposed to γ-radiation (25). Also, Lakhani et al. (26) demonstrated that caspase-3 and -7 are key mediators of Bax-directed mitochondrial apoptotic events in response to ultraviolet radiation.

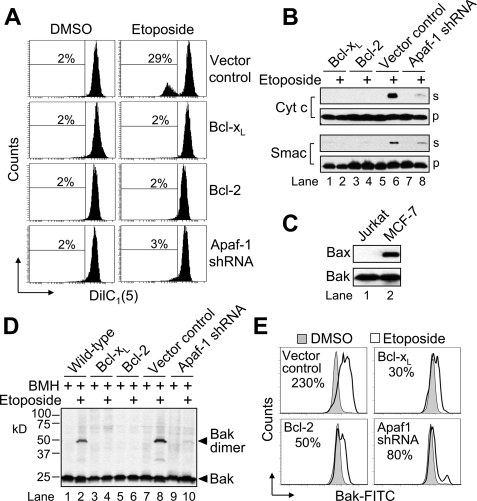

Having demonstrated that Jurkat cells in which either an anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family protein had been overexpressed or Apaf-1 had been knocked down, were equally impaired in their ability to activate caspases, we next evaluated the different cells for changes in Δψ. As illustrated in Fig. 2A, a partial loss of Δψ in response to 10 μm etoposide was detected in control-transfected Jurkat cells, which activated caspases (Fig. 1C), whereas Apaf-1-deficient and Bcl-2/Bcl-xL-overexpressing cells did not lose Δψ. These data are consistent with evidence indicating that the loss of Δψ during apoptotic cell death requires caspase-mediated proteolytic inactivation of the respiratory complex I subunit NDUSF1 (27). Because a drop in Δψ is often associated with the release of mitochondrial intermembrane space proteins into the cytosol, we next investigated whether the release of cytochrome c and Smac had occurred in the different cell types. Consistent with the membrane potential results, etoposide treatment stimulated a strong release of cytochrome c and Smac only in vector control cells (Fig. 2B, lane 6 versus 5). By comparison, cells overexpressing either Bcl-2 or Bcl-xL failed to release cytochrome c or Smac in response to etoposide (Fig. 2B, lanes 1–4), and Apaf-1-deficient cells released only a trace of each protein (lane 8 versus 7).

FIGURE 2.

Apaf-1 is essential for MOMP induction and Bak activation in response to etoposide. A, control-transfected, Bcl-xL- and Bcl-2-overexpressing, and Apaf-1-deficient Jurkat clones (106/ml) were cultured in the presence or absence of DMSO or 10 μm etoposide for 6 h, harvested, and processed for mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨ) determination by flow cytometry. Reduced DiIC1(5) fluorescence is indicative of a loss of ΔΨ, and numbers refer to the percentage of cells that underwent a dissipation of ΔΨ. B, duplicate aliquots of cells in A were harvested and processed for subcellular fractionation. Supernatant (s) and pellet (p) fractions were analyzed by Western blotting. Cyt c, cytochrome c. C, whole-cell lysates of Jurkat (E6.1) and MCF-7 (positive control for Bax expression) cells were separated by SDS-PAGE and Western-blotted. D and E, wild-type, control-transfected, Bcl-xL- and Bcl-2-overexpressing, and Apaf-1-deficient Jurkat clones (106/ml) were cultured in the absence or presence of DMSO or 10 μm etoposide for 6 h and processed for determination of Bak oligomerization by Western blotting (D) or Bak activation by flow cytometric analysis (E). Numbers in E refer to the percentage increase in Bak-associated fluorescence between etoposide- and DMSO-treated samples. shRNA, short hairpin RNA; BMH, bismaleimidohexane.

Numerous studies from other laboratories have shown that the induction of MOMP is tightly controlled by pro- and anti-apoptotic members of the Bcl-2 family of proteins (2, 28). In fact, it is often the ratio of pro- to anti-apoptotic proteins that determines the sensitivity of a cell to a given intrinsic apoptotic stimulus. Induction of MOMP by either of the multidomain pro-apoptotic proteins Bax and Bak is thought to require the prior activation of a BH3-only Bcl-2 family protein (29). The anti-apoptotic proteins Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL prevent MOMP by directly binding Bax/Bak or by preventing their activation by inhibiting BH3-only proteins (30). As mentioned earlier, Bax is largely cytosolic in healthy cells, whereas Bak resides on the outer mitochondrial membrane. Both proteins are monomeric in their inactive state, and activation coincides with their homo-oligomerization to form protein-permeable pores in the outer mitochondrial membrane.

To investigate the extent to which differences in the release of cytochrome c and Smac corresponded to differences in the activation of Bax or Bak, we first evaluated the different cell clones for the expression of Bax and Bak. Interestingly, Western blot results revealed that Jurkat (E6.1) cells express Bak, but not Bax, protein (Fig. 2C, lane 1). Thus, to evaluate changes in Bak under the different conditions, we first investigated whether Bak underwent oligomerization using the cross-linking agent bismaleimidohexane. As illustrated in Fig. 2D, cross-linked Bak complexes consistent with dimers were observed in wild-type (lane 2) and control-transfected (lane 8) Jurkat cells treated with 10 μm etoposide for 6 h. These findings were in agreement with results obtained using an active conformation-specific monoclonal Bak antibody and flow cytometric analysis, where Bak activation amounts to a shift to the right in the resulting histogram (Fig. 2E). Consistent with previous reports, etoposide-induced oligomerization (Fig. 2D) and activation (Fig. 2E) of Bak were blocked in cells overexpressing Bcl-2 or Bcl-xL, perhaps because of their reported ability to sequester activator BH3-only proteins (6) or to bind Bak directly (7, 8). Significantly, Bak oligomerization and activation were also strongly inhibited in Apaf-1-deficient Jurkat cells (Fig. 2D, lane 10 versus 9, and E), which likely accounts for the lack of cytochrome c and Smac release in these cells following etoposide treatment (Fig. 2B, lane 8 versus 7). Combined, these data raise the distinct possibility that signaling events, which are widely believed to be post-mitochondrial, are essential for Bak-mediated cytochrome c release and dissipation of Δψ during true intrinsic apoptotic cell death.

Overexpression of Full-length XIAP or the BIR1/BIR2 Domains of XIAP Inhibits Etoposide-induced Apoptosis—Because Bak activation and MOMP were strongly inhibited in Apaf-1-deficient cells, we were next interested to determine whether this was due to a direct role of Apaf-1 in mediating MOMP or whether the absence of Bak activation and the release of intermembrane space proteins were attributable to the lack of etoposide-induced caspase activation. Because of the reported problems with the selectivity of “specific” peptide-based caspase inhibitors (31, 32), we developed a genetic strategy to inhibit caspases residing downstream of apoptosome formation. The approach was to modulate the expression of XIAP.

XIAP is a member of the inhibitor of apoptosis protein family that potently inhibits apoptotic cell death by specifically targeting caspase-9, -3, and/or -7 (33). Recent work has described the regions of XIAP that are responsible for its caspase inhibitory properties (34, 35). Specifically, a region of XIAP that includes the BIR2 domain inhibits caspase-3 and -7, whereas the BIR3 domain inhibits caspase-9. In a cell dying by apoptosis, the anti-apoptotic activity of XIAP can be inhibited by two mitochondrial intermembrane space proteins, namely Smac (36, 37) and Omi (38–40), that are released into the cytosol, along with cytochrome c, following the induction of MOMP.

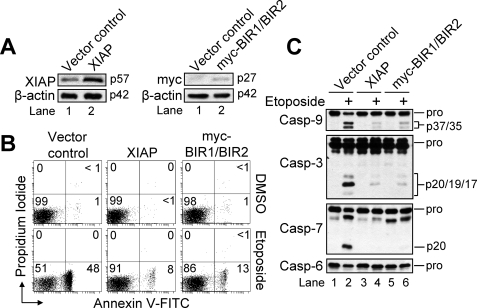

For our studies, we generated Jurkat cells that overexpressed either full-length XIAP (Fig. 3A, left panel) or the BIR1/BIR2 domains of XIAP (right panel). We hypothesized that, if full-length XIAP inhibited Bak activation and MOMP, then cells expressing only the BIR1/BIR2 domains would shed light on whether this was largely a caspase-9- or caspase-3/7-mediated effect. The primary justification for expressing BIR1/BIR2, instead of BIR2 alone, is that XIAP-BIR1/BIR2 has been shown to express better in mammalian cells than XIAP-BIR2 alone (34). As illustrated in Fig. 3B, vector control cells underwent apoptosis (∼48%) when incubated in the presence of 10 μm etoposide for 6 h. By comparison, cells overexpressing full-length XIAP or the BIR1/BIR2 domains underwent ∼8 and ∼13% apoptosis, respectively. Western blot analysis of cell lysates generated after 6 h of etoposide incubation revealed that extensive cleavage of caspase-9, -3, and -7 had occurred, as well as the partial disappearance of the precursor form of caspase-6, only in control-transfected cells (Fig. 3C). Overall, these findings demonstrate that cells overexpressing either XIAP or the BIR1/BIR2 domains of XIAP are similarly protected from etoposide-induced apoptosis.

FIGURE 3.

Overexpression of XIAP or Myc-BIR1/BIR2 inhibits etoposide-induced apoptosis. A, control-transfected, XIAP-overexpressing, and Myc-BIR1/BIR2-overexpressing Jurkat clones were harvested and lysed for Western blotting. β-Actin was used as a loading control. B, cells (106/ml) were cultured with DMSO or 10 μm etoposide for 6 h and processed for cell death determination by flow cytometric analysis of annexin V-FITC and propidium iodide staining. Quadrants are defined as live (lower left), early apoptotic (lower right), late apoptotic (upper right), and necrotic (upper left). Numbers refer to the percentage of cells in each quadrant. C, duplicate aliquots of cells in B were harvested and lysed for Western blotting. Casp, caspase.

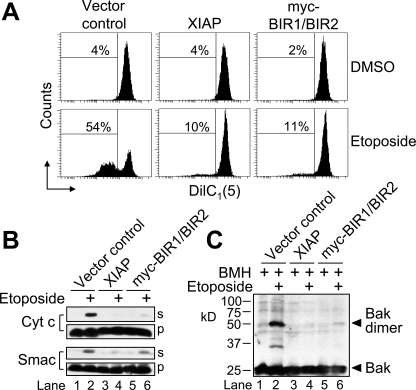

Activation of Bak and Induction of MOMP Are Dependent on Downstream Caspase Activation—Once we had demonstrated that cells expressing either of the two XIAP constructs were similarly resistant to etoposide-induced apoptosis, the next step was to determine the extent to which this involved an inhibition of mitochondrial apoptotic events. As illustrated in Fig. 4A, slightly more than half of the etoposide-treated vector control cells experienced a loss of Δψ, whereas XIAP- and BIR1/BIR2-overexpressing cells underwent a more modest drop in Δψ of ∼10 and 11%, respectively. In agreement with the Δψ findings, vector control cells were triggered to undergo etoposide-induced MOMP as assessed by Western blot analysis of cytochrome c and Smac release into the cytosol (Fig. 4B, lane 2 versus 1). By comparison, XIAP overexpressors, and to a slightly lesser extent BIR1/BIR2-expressing cells, were refractory to etoposide-induced cytochrome c and Smac release (Fig. 4B, lanes 3–6). Finally, we were interested to know whether the inhibition of cytochrome c and Smac release in the XIAP- and BIR1/BIR2-overexpressing cells coincided with a similar inhibition of Bak activation in cells incubated with etoposide. As shown in Fig. 4C, the results indicated that incubation of vector control cells with 10 μm etoposide for 6 h induced large-scale Bak oligomerization (lane 2). By comparison, etoposide-treated XIAP-overexpressing cells failed to activate Bak (Fig. 4C, lane 4), and only a trace amount of active Bak was detected in BIR1/BIR2-expressing cells (lane 6). Taken together, these findings strongly suggest that downstream caspases play an essential role in the activation of Bak and in the induction of MOMP during etoposide-induced apoptosis. They also imply that the reason etoposide-induced mitochondrial apoptotic events were inhibited in Apaf-1-deficient cells is due to the fact that caspases were not activated, rather than any direct role for Apaf-1 in mediating Bak activation or MOMP.

FIGURE 4.

Downstream caspases play an integral role in Bak activation and MOMP induction. A, control-transfected, XIAP-overexpressing, and Myc-BIR1/BIR2-expressing Jurkat clones (106/ml) were cultured in the presence or absence of DMSO or 10 μm etoposide for 6 h, harvested, and processed for ΔΨ determination by flow cytometry. Reduced DiIC1(5) fluorescence is indicative of a loss of ΔΨ, and numbers refer to the percentage of cells that underwent a dissipation of ΔΨ. B, duplicate aliquots of cells in A were harvested and processed for subcellular fractionation. Supernatant (s) and pellet (p) fractions were analyzed by Western blotting. C, cells were cultured as described in A and processed for determination of Bak oligomerization by Western blotting. BMH, bismaleimidohexane; Cyt c, cytochrome c.

Concluding Remarks—Ever since Wang and colleagues (41) made the seminal observation that the induction of the apoptotic program in cell-free extracts requires cytochrome c (and dATP), a major effort has been made to characterize the molecular mechanisms responsible for the regulation of the intrinsic (mitochondria-mediated) apoptotic pathway. A more complete understanding of how this pathway is regulated has ensued, and it is now widely accepted that various cytotoxic stressors kill cells by activating the intrinsic pathway.

As mentioned previously, one of the earliest events during true intrinsic apoptosis is the activation of Bax and/or Bak (4). Under unstressed conditions, Bax and Bak can be found in the cytosol and on the outer mitochondrial membrane, respectively, as monomers (30). Activation of Bax and Bak is marked by their homo-oligomerization to form pores in the outer mitochondrial membrane through which intermembrane space proteins, including cytochrome c, can be released into the cytosol to promote apoptosome-dependent activation of caspases. Although caspase-8-mediated cleavage of Bid to tBid is known to play an important role in the activation of Bak or Bax during receptor-mediated apoptosis in type II cells, the underlying mechanism responsible for the activation of these multidomain pro-apoptotic proteins within the intrinsic apoptotic pathway is not well understood. In cells with normal p53, genotoxic anticancer drugs have been suggested to activate Bax/Bak because of a transcriptional up-regulation of Puma (42, 43). However, because cancer cells, including Jurkat (E6.1), are often defective in their p53 signaling pathway, a general non-redundant role for Puma up-regulation seems unlikely. In fact, most evidence in the literature indicates that stress-induced activation of Bak and Bax requires the presence of either Bid or Bim, irrespective of p53 status (29). However, insight into the precise mechanism(s) responsible for the activation of these two BH3-only proteins in response to genotoxic injury is currently lacking.

A common view of the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway is that cytochrome c release is an all-or-none phenomenon in that, once a single mitochondrion in an “apoptosing” cell has released its cytochrome c, all mitochondria in that cell will release all of their cytochrome c within about 10 min (2, 22, 44, 45). Two additional viewpoints are (i) procaspase-9 activation occurs in a cytochrome c-dependent manner involving the formation of an Apaf-1 apoptosome complex, and (ii) the release of cytochrome c and other intermembrane space proteins from mitochondria occurs by a mechanism that is independent of downstream caspases (1, 23, 24, 45, 46). However, our observations, as well as other lines of evidence, do not support a strictly linear view of the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway. As mentioned previously, a cytochrome c- and apoptosome-independent, but Apaf-1-dependent, mechanism leading to caspase activation has been described (25). Also, there is evidence that caspase-3 and -7 can be key mediators of Bax-directed mitochondrial apoptotic events in response to UV radiation (26). Furthermore, our results demonstrate that downstream caspases are required for Bak activation and MOMP induction in response to the genotoxic drug etoposide in Jurkat cells.

In summary, our findings support a model of the intrinsic pathway in which caspase-mediated positive amplification of initial mitochondrial events can function as an essential part of cell death and, as such, may determine whether a given cell dies in response to stress. Furthermore, it is tempting to speculate that at least one reason a single biologically active apoptosome complex is around 1 MDa in size (47, 48) and consists of seven Apaf-1 and cytochrome c molecules coassembling to form a wheel-like complex with seven spokes (49) is to prevent the unintentional activation of caspase-9. In other words, it seems plausible that, in instances in which a weak apoptotic signal induces the release of miniscule amounts of cytochrome c or if mitochondria leak trace amounts of cytochrome c during normal turnover of these organelles, a cell would not necessarily die unless enough cytochrome c had been released to support sufficient apoptosome-mediated activation of caspase-9 molecules. Even then, it is conceivable that activation of caspase-9 might not always signal the end of the road for a cell if the level of activity that ensues is not sufficient to activate enough executioner caspase-3 or -7 molecules to kill a cell outright and/or promote the positive amplification of initial mitochondrial apoptotic events.

Acknowledgments

We thank Beth Walsh and Emily Franklin for expert technical help and Dr. Joyce Slusser for invaluable assistance with flow cytometry. We thank Dr. Emad Alnemri for the pcDNA3-XIAP and pcDNA3-Myc-BIR1/BIR2 mammalian expression vectors and the late Dr. Stanley Korsmeyer for the pSFFV-neo, pSFFV-Bcl-2, and pSFFV-Bcl-xL mammalian expression vectors.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants K22 ES011647 (to J. D. R.) and P20 RR016475 from the IDeA Networks of Biomedical Research Excellence Program of the NCRR. The Flow Cytometry Core is supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grant P20 RR016443 from the National Center for Research Resources. The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement”in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: MOMP, mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization; Smac, second mitochondria-derived activator of caspase; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; XIAP, X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein; BIR, baculoviral inhibitor of apoptosis protein repeat; tBid, truncated Bid; BH3, Bcl-2 homology 3; FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate; Apaf-1, apoptotic protease-activating factor-1; DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide.

S. N. Shelton, M. E. Shawgo, and J. D. Robertson, unpublished results.

References

- 1.Li, P., Nijhawan, D., Budihardjo, I., Srinivasula, S. M., Ahmad, M., Alnemri, E. S., and Wang, X. (1997) Cell 91 479–489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chipuk, J. E., Bouchier-Hayes, L., and Green, D. R. (2006) Cell Death Differ. 13 1396–1402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ow, Y. L., Green, D. R., Hao, Z., and Mak, T. W. (2008) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 9 532–542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wei, M. C., Zong, W. X., Cheng, E. H., Lindsten, T., Panoutsakopoulou, V., Ross, A. J., Roth, K. A., MacGregor, G. R., Thompson, C. B., and Korsmeyer, S. J. (2001) Science 292 727–730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lindsten, T., Ross, A. J., King, A., Zong, W. X., Rathmell, J. C., Shiels, H. A., Ulrich, E., Waymire, K. G., Mahar, P., Frauwirth, K., Chen, Y., Wei, M., Eng, V. M., Adelman, D. M., Simon, M. C., Ma, A., Golden, J. A., Evan, G., Korsmeyer, S. J., MacGregor, G. R., and Thompson, C. B. (2000) Mol. Cell 6 1389–1399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim, H., Rafiuddin-Shah, M., Tu, H. C., Jeffers, J. R., Zambetti, G. P., Hsieh, J. J., and Cheng, E. H. (2006) Nat. Cell Biol. 8 1348–1358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen, L., Willis, S. N., Wei, A., Smith, B. J., Fletcher, J. I., Hinds, M. G., Colman, P. M., Day, C. L., Adams, J. M., and Huang, D. C. (2005) Mol. Cell 17 393–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Willis, S. N., Fletcher, J. I., Kaufmann, T., van Delft, M. F., Chen, L., Czabotar, P. E., Ierino, H., Lee, E. F., Fairlie, W. D., Bouillet, P., Strasser, A., Kluck, R. M., Adams, J. M., and Huang, D. C. (2007) Science 315 856–859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li, H., Zhu, H., Xu, C. J., and Yuan, J. (1998) Cell 94 491–501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Luo, X., Budihardjo, I., Zou, H., Slaughter, C., and Wang, X. (1998) Cell 94 481–490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Robertson, J. D., Enoksson, M., Suomela, M., Zhivotovsky, B., and Orrenius, S. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277 29803–29809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garrido, C., Galluzzi, L., Brunet, M., Puig, P. E., Didelot, C., and Kroemer, G. (2006) Cell Death Differ. 13 1423–1433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Friesen, C., Herr, I., Krammer, P. H., and Debatin, K. M. (1996) Nat. Med. 2 574–577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kasibhatla, S., Brunner, T., Genestier, L., Echeverri, F., Mahboubi, A., and Green, D. R. (1998) Mol. Cell 1 543–551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Petak, I., Tillman, D. M., Harwood, F. G., Mihalik, R., and Houghton, J. A. (2000) Cancer Res. 60 2643–2650 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Juo, P., Kuo, C. J., Yuan, J., and Blenis, J. (1998) Curr. Biol. 8 1001–1008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gogvadze, V., Orrenius, S., and Zhivotovsky, B. (2006) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1757 639–647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guo, Y., Srinivasula, S. M., Druilhe, A., Fernandes-Alnemri, T., and Alnemri, E. S. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277 13430–13437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bonzon, C., Bouchier-Hayes, L., Pagliari, L. J., Green, D. R., and Newmeyer, D. D. (2006) Mol. Biol. Cell 17 2150–2157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Upton, J. P., Austgen, K., Nishino, M., Coakley, K. M., Hagen, A., Han, D., Papa, F. R., and Oakes, S. A. (2008) Mol. Cell. Biol. 28 3943–3951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Franklin, E. E., and Robertson, J. D. (2007) Biochem. J. 405 115–122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goldstein, J. C., Waterhouse, N. J., Juin, P., Evan, G. I., and Green, D. R. (2000) Nat. Cell Biol. 2 156–162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bossy-Wetzel, E., Newmeyer, D. D., and Green, D. R. (1998) EMBO J. 17 37–49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sun, X. M., MacFarlane, M., Zhuang, J., Wolf, B. B., Green, D. R., and Cohen, G. M. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274 5053–5060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hao, Z., Duncan, G. S., Chang, C. C., Elia, A., Fang, M., Wakeham, A., Okada, H., Calzascia, T., Jang, Y., You-Ten, A., Yeh, W. C., Ohashi, P., Wang, X., and Mak, T. W. (2005) Cell 121 579–591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lakhani, S. A., Masud, A., Kuida, K., Porter, G. A., Jr., Booth, C. J., Mehal, W. Z., Inayat, I., and Flavell, R. A. (2006) Science 311 847–851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ricci, J. E., Munoz-Pinedo, C., Fitzgerald, P., Bailly-Maitre, B., Perkins, G. A., Yadava, N., Scheffler, I. E., Ellisman, M. H., and Green, D. R. (2004) Cell 117 773–786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scorrano, L., and Korsmeyer, S. J. (2003) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 304 437–444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Letai, A. G. (2008) Nat. Rev. Cancer 8 121–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Youle, R. J., and Strasser, A. (2008) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 9 47–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Berger, A. B., Sexton, K. B., and Bogyo, M. (2006) Cell Res. 16 961–963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McStay, G. P., Salvesen, G. S., and Green, D. R. (2008) Cell Death Differ. 15 322–331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Deveraux, Q. L., Takahashi, R., Salvesen, G. S., and Reed, J. C. (1997) Nature 388 300–304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Scott, F. L., Denault, J. B., Riedl, S. J., Shin, H., Renatus, M., and Salvesen, G. S. (2005) EMBO J. 24 645–655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shiozaki, E. N., Chai, J., Rigotti, D. J., Riedl, S. J., Li, P., Srinivasula, S. M., Alnemri, E. S., Fairman, R., and Shi, Y. (2003) Mol. Cell 11 519–527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Du, C., Fang, M., Li, Y., Li, L., and Wang, X. (2000) Cell 102 33–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Verhagen, A. M., Ekert, P. G., Pakusch, M., Silke, J., Connolly, L. M., Reid, G. E., Moritz, R. L., Simpson, R. J., and Vaux, D. L. (2000) Cell 102 43–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hegde, R., Srinivasula, S. M., Zhang, Z., Wassell, R., Mukattash, R., Cilenti, L., DuBois, G., Lazebnik, Y., Zervos, A. S., Fernandes-Alnemri, T., and Alnemri, E. S. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277 432–438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Suzuki, Y., Imai, Y., Nakayama, H., Takahashi, K., Takio, K., and Takahashi, R. (2001) Mol. Cell 8 613–621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Verhagen, A. M., Silke, J., Ekert, P. G., Pakusch, M., Kaufmann, H., Connolly, L. M., Day, C. L., Tikoo, A., Burke, R., Wrobel, C., Moritz, R. L., Simpson, R. J., and Vaux, D. L. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277 445–454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu, X., Kim, C. N., Yang, J., Jemmerson, R., and Wang, X. (1996) Cell 86 147–157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jeffers, J. R., Parganas, E., Lee, Y., Yang, C., Wang, J., Brennan, J., MacLean, K. H., Han, J., Chittenden, T., Ihle, J. N., McKinnon, P. J., Cleveland, J. L., and Zambetti, G. P. (2003) Cancer Cell 4 321–328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Villunger, A., Michalak, E. M., Coultas, L., Mullauer, F., Bock, G., Ausserlechner, M. J., Adams, J. M., and Strasser, A. (2003) Science 302 1036–1038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Goldstein, J. C., Munoz-Pinedo, C., Ricci, J. E., Adams, S. R., Kelekar, A., Schuler, M., Tsien, R. Y., and Green, D. R. (2005) Cell Death Differ. 12 453–462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Waterhouse, N. J., Goldstein, J. C., von Ahsen, O., Schuler, M., Newmeyer, D. D., and Green, D. R. (2001) J. Cell Biol. 153 319–328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wilkinson, J. C., Cepero, E., Boise, L. H., and Duckett, C. S. (2004) Mol. Cell Biol. 24 7003–7014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cain, K., Bratton, S. B., Langlais, C., Walker, G., Brown, D. G., Sun, X. M., and Cohen, G. M. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275 6067–6070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zou, H., Li, Y., Liu, X., and Wang, X. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274 11549–11556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Acehan, D., Jiang, X., Morgan, D. G., Heuser, J. E., Wang, X., and Akey, C. W. (2002) Mol. Cell 9 423–432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]