Abstract

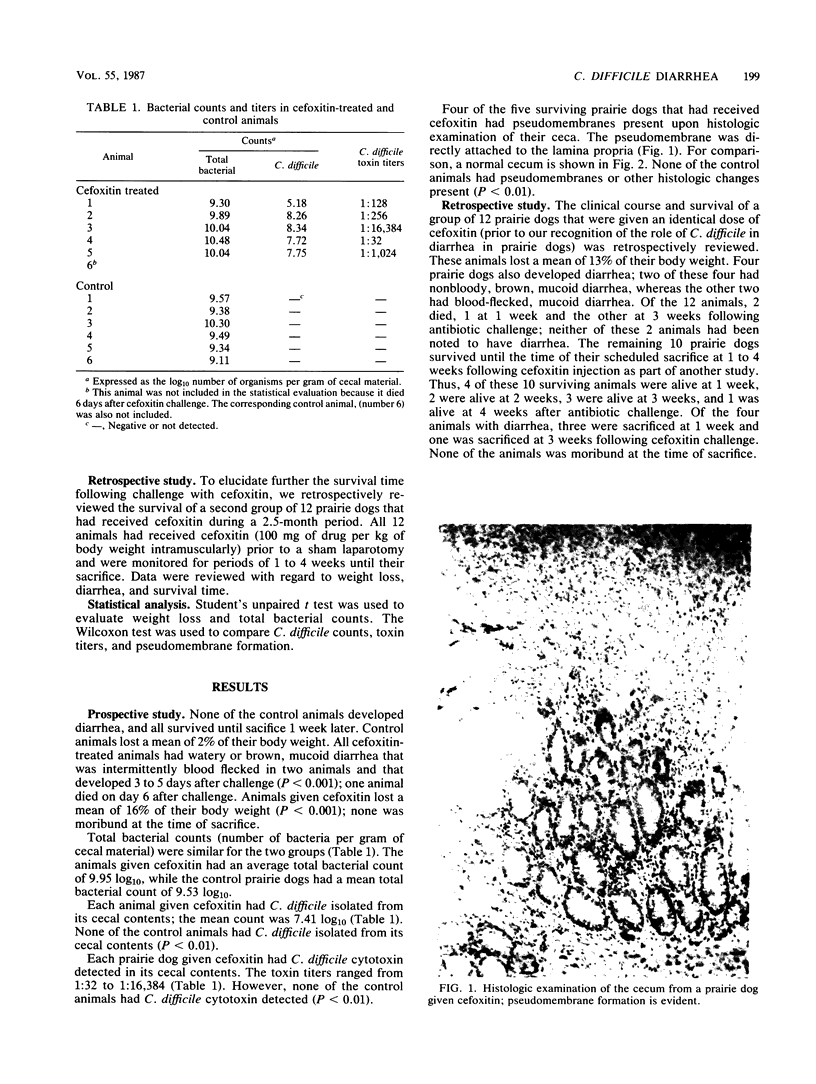

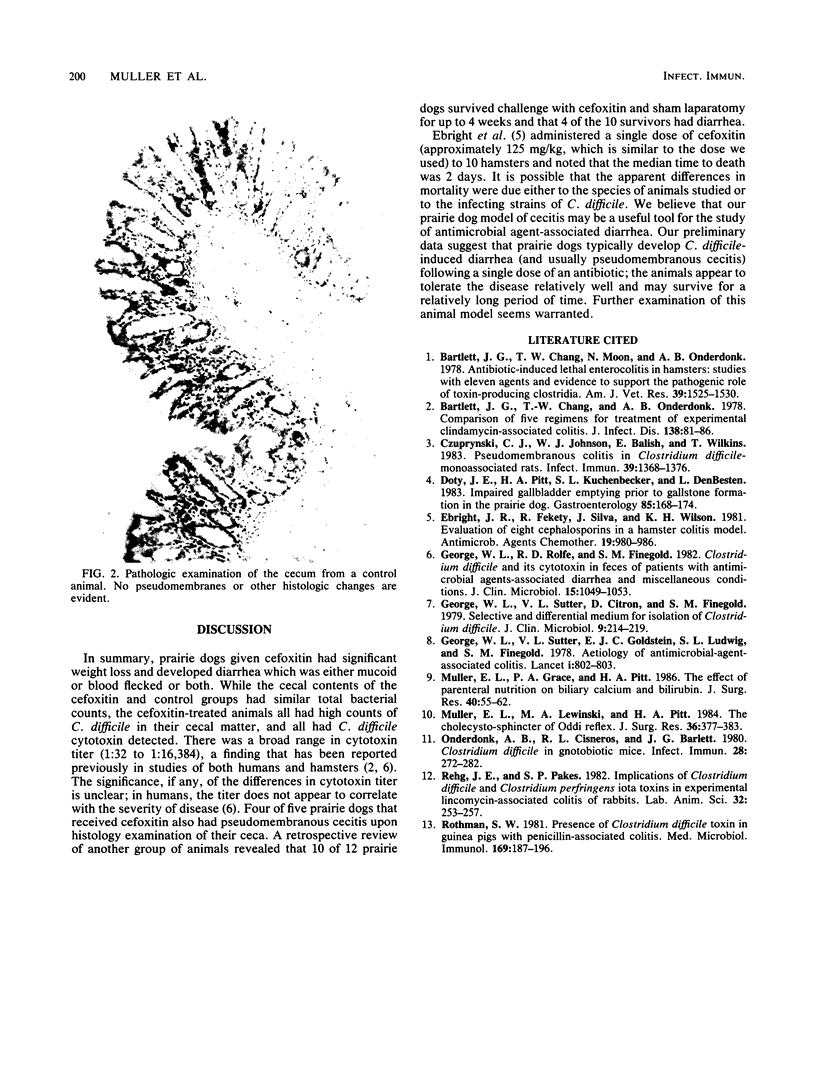

We have noted that prairie dogs given cefoxitin develop diarrhea and lose weight yet survive for periods of up to 4 weeks. Therefore, we tested the hypothesis that cefoxitin causes Clostridium difficile cecitis in prairie dogs. Six prairie dogs were given a single intramuscular dose of 100 mg of cefoxitin per kg of body weight, and six control animals received saline; both groups were sacrificed 1 week later. Controls had no diarrhea and lost 2% of their body weight, whereas cefoxitin-treated animals had diarrhea (P less than 0.001) and lost 16% of their body weight (P less than 0.001); one animals died 6 days after cefoxitin challenge. None of the controls yielded C. difficile or had cecal cytotoxin or pseudomembranes detected. Cecal contents from all cefoxitin-treated animals, however, yielded C. difficile (P less than 0.01) and had cecal cytotoxin present (P less than 0.01). Four of five surviving animals also had cecal pseudomembranes present (P less than 0.01). These results demonstrate that in prairie dogs cefoxitin induces C. difficile cecitis. We conclude that the prairie dog is another model for the study of antibiotic-induced diarrhea. The disease in prairie dogs may have a more chronic course than in other animal models of C. difficile-induced diarrhea and may be useful as a model for studying certain aspects of C. difficile-induced diarrhea.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Bartlett J. G., Chang T. W., Moon N., Onderdonk A. B. Antibiotic-induced lethal enterocolitis in hamsters: studies with eleven agents and evidence to support the pathogenic role of toxin-producing Clostridia. Am J Vet Res. 1978 Sep;39(9):1525–1530. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett J. G., Chang T. W., Onderdonk A. B. Comparison of five regimens for treatment of experimental clindamycin-associated colitis. J Infect Dis. 1978 Jul;138(1):81–86. doi: 10.1093/infdis/138.1.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czuprynski C. J., Johnson W. J., Balish E., Wilkins T. Pseudomembranous colitis in Clostridium difficile-monoassociated rats. Infect Immun. 1983 Mar;39(3):1368–1376. doi: 10.1128/iai.39.3.1368-1376.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doty J. E., Pitt H. A., Kuchenbecker S. L., DenBesten L. Impaired gallbladder emptying before gallstone formation in the prairie dog. Gastroenterology. 1983 Jul;85(1):168–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebright J. R., Fekety R., Silva J., Wilson K. H. Evaluation of eight cephalosporins in hamster colitis model. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1981 Jun;19(6):980–986. doi: 10.1128/aac.19.6.980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George W. L., Rolfe R. D., Finegold S. M. Clostridium difficile and its cytotoxin in feces of patients with antimicrobial agent-associated diarrhea and miscellaneous conditions. J Clin Microbiol. 1982 Jun;15(6):1049–1053. doi: 10.1128/jcm.15.6.1049-1053.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George W. L., Sutter V. L., Citron D., Finegold S. M. Selective and differential medium for isolation of Clostridium difficile. J Clin Microbiol. 1979 Feb;9(2):214–219. doi: 10.1128/jcm.9.2.214-219.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George W. L., Sutter V. L., Goldstein E. J., Ludwig S. L., Finegold S. M. Aetiology of antimicrobial-agent-associated colitis. Lancet. 1978 Apr 15;1(8068):802–803. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(78)93001-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller E. L., Grace P. A., Pitt H. A. The effect of parenteral nutrition on biliary calcium and bilirubin. J Surg Res. 1986 Jan;40(1):55–62. doi: 10.1016/0022-4804(86)90145-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller E. L., Lewinski M. A., Pitt H. A. The cholecysto-sphincter of Oddi reflex. J Surg Res. 1984 Apr;36(4):377–383. doi: 10.1016/0022-4804(84)90114-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onderdonk A. B., Cisneros R. L., Bartlett J. G. Clostridium difficile in gnotobiotic mice. Infect Immun. 1980 Apr;28(1):277–282. doi: 10.1128/iai.28.1.277-282.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehg J. E., Pakes S. P. Implication of Clostridium difficile and Clostridium perfringens iota toxins in experimental lincomycin-associated colitis of rabbits. Lab Anim Sci. 1982 Jun;32(3):253–257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothman S. W. Presence of Clostridium difficile toxin in guinea pigs with penicillin-associated colitis. Med Microbiol Immunol. 1981;169(3):187–196. doi: 10.1007/BF02123592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]