Abstract

The high mobility group (HMG) proteins, including HMGA, HMGB and HMGN, are abundant and ubiquitous nuclear proteins that bind to DNA, nucleosome and other multi-protein complexes in a dynamic and reversible fashion to regulate DNA processing in the context of chromatin. All HMG proteins, like histone proteins, are subjected to extensive post-translational modifications (PTMs), such as lysine acetylation, arginine/lysine methylation and serine/threonine phosphorylation, to modulate their interactions with DNA and other proteins. There is a growing appreciation for the complex relationship between the PTMs of HMG proteins and their diverse biological activities. Here, we reviewed the identified covalent modifications of HMG proteins, and highlighted how these PTMs affect the functions of HMG proteins in a variety of cellular processes.

Keywords: High mobility group protein, post-translational modification, mass spectrometry

Introduction

Nucleosome, the basic chromatin unit, is composed of DNA and core histones (H2A, H2B, H3 and H4) and organized into high-order structures by diverse proteins including histone H1 and high mobility group (HMG) proteins. After histone proteins, HMG proteins are the second most abundant chromosomal proteins that are thought to play important roles in remodeling the assembly of chromatin and in regulating gene transcription in higher eukaryotic cells by distorting, bending or modifying the structure of DNA, which is bound with histones and transcriptional factors [1, 2]. HMG proteins, exhibiting molar masses of less than 30 kDa and relatively high mobility in acidic (pH 2.4) polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis system, were identified more than 30 years ago by Goodwin [3]. All HMG proteins bind to chromatin in a dynamic and reversible fashion and provide flexibility to chromatin to tune finely gene transcription either positively or negatively. Although the HMG proteins have never attracted the same degree of attention as histone proteins, they have been recently recognized to have essential roles in a variety of cellular processes, including cancer development [4], DNA repair [5] and infectious/inflammatory disorder [6].

All HMG proteins, like histone proteins, are subjected to a number of post-translational modifications (PTMs), such as lysine acetylation, arginine/lysine methylation and serine/threonine phosphorylation, which modulate their interactions with DNA and other proteins [7]. There is a growing appreciation for the complex relationship between the PTMs of HMG proteins and their diverse biological activities. Although the biological effects induced by the PTMs of HMG proteins are still not fully understand, new insights into the mechanism of the modification “code” have emerged from the increasing appreciation of the functions of these proteins in a variety of cellular processes from studies of human diseases and the development of mass spectrometric techniques.

General overviews of HMG proteins as well as different subfamilies of HMG proteins have been written by a couple of groups [2, 7–11]. Various reviews focusing on different aspects of HMG proteins are also available: The roles of HMG proteins in various diseases were reviewed by Fusco [4], Mantell [6] and Hock [12]; the implications of HMG proteins in DNA damage and repair were reviewed recently by Reeves [5] and Travers [13]; the detailed method for the preparation of different HMG family proteins were also described [14–17]. In this review, we will first discuss briefly the HMG protein members, their structure, function and implications in human diseases. We will then discuss in detail the post-translational modifications of the three families of mammalian HMG proteins, and highlight how these PTMs affect the functions of the HMG proteins in an array of cellular processes.

HMG Protein Members, Their Structure, Function and Implications in Human Diseases

HMG Protein Members

Three distinct families of HMG proteins have been defined and named based on the structure of their DNA binding domains and their substrate binding specificity, including HMG-AT-hook families (HMGA), HMG-box families (HMGB) and HMG-nucleosome binding families (HMGN) [18]. The former name and general characteristics of each HMG members are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Nomenclature and general characteristics of human HMG proteins

| Family Members | Former Names | Swiss-Prot | Length (aa) | Mass (Da) | DNA binding domains | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HMGA | HMGA1a | HMGI | P17096-1 | 106 | 11544 | AT-hooks, binding to the minor groove of AT-rich DNA stretches |

| HMGA1b | HMGY | P17096-2 | 95 | 10547 | ||

| HMGA2 | HMGI-C | P52926 | 108 | 11700 | ||

| HMGB | HMGB1 | HMG-I | P09429 | 214 | 24762 | HMG Boxes, binding to the minor groove of DNA with limited or no sequence specificity |

| HMGB2 | HMG-2 | P26583 | 208 | 23902 | ||

| HMGB3 | HMG-4 | O15347 | 199 | 22848 | ||

| HMGN | HMGN1 | HMG-14 | P05114 | 99 | 10527 | Binding directly to nucleosomes, between the DNA spires and the histone octamer |

| HMGN2 | HMG-17 | P05204 | 89 | 9261 | ||

| HMGN3a | TRIP-7 | Q15651-1 | 98 | 10534 | ||

| HMGN3b | TRIP-7 | Q15651-2 | 76 | 8246 | ||

| HMGN4 | HMG17L3 | O00479 | 89 | 9407 |

The HMGA proteins comprise of HMGA1a, HMGA1b and HMGA2, and they can bind to the minor groove of AT-rich DNA stretches via the three domains called “AT-hooks” [19]. HMGA1a and HMGA1b, formerly known as HMG-I and HMG-Y, respectively, are the products of the same gene (HMGA1), and they are identical in sequence except for an 11-amino acid internal deletion in HMGA1b due to alternative splicing [20, 21]. HMGA2, which is coded by a different gene (HMGA2), distinguishes from HMGA1a in the first 25 amino-acid residues, and it contains a short peptide located between the third AT-hook and the acidic tail, which is absent in HMGA1a [22].

The HMGB proteins contain HMG boxes which can bind to the minor groove of DNA with limited or no sequence specificity both in vitro and in vivo [23, 24] and produce a strong bend in DNA backbone. Human HMGB proteins include HMGB1 (formerly known as HMG1), HMGB2 (formerly HMG2) and HMGB3, which are encoded by HMGB1, HMGB2 and HMGB3 genes, respectively [25].

The HMGN family, which binds specifically to the 147-base pair nucleosome core particle, consists of four closely related proteins with a molecular weight of ~10 kDa: HMGN1 (previously known as HMG-14), HMGN2 (previously known as HMG-17), HMGN3 (previously known as Trip-7) as well as the recently identified member of HMGN4 [26].

Structure of HMG Proteins

All HMGA proteins adopt similar structure, carrying three AT-hooks, which are involved in binding to the minor groove of AT-rich DNA as stated above, and an acidic carboxyl-terminus, and are well conserved during evolution. While HMGA1 proteins are well-known to be capable of binding to the minor groove of AT-rich DNA, they can also bind to four-way junctions [27, 28].

Mammalian HMGB proteins, representing a small subset of HMG-box proteins, contain two tandem HMG boxes connected by a basic linker to a highly acidic tail [29], whereas most HMG-box proteins have a single HMG box. HMG box has a characteristic domain of about 80 amino-acid residues consisting of three α helices arranged in an “L” shape with an angle of ~ 80° between the arms, and a concave surface which can fit into the minor groove of duplex DNA [9]. The two box domains (A- and B-domain) in HMGB proteins are structurally similar, but the A-domain shows a much higher preference for distorted DNA than the B-domain [30, 31]. While the B-domain can introduce an approximately right-angled bend into linear DNA, the A-domain is unable to bend DNA effectively [31, 32]. In general, HMGB binds preferentially to distorted DNA structure, such as four-way junctions [33], cisplatin- and UV-damaged DNA [34–36].

The HMGN proteins carry a characteristic nucleosome-binding domain (NBD), a positively charged region of 30 amino-acid residues [11]. Aside from the NBD domain, HMGN proteins bear a bipartite nuclear localization signal (NLS) [37] and a chromatin unfolding domain (CHUD) [38, 39].

Functions of HMG Proteins and Their Implications in Human Diseases

HMGA1 proteins, considered as “hubs” of nuclear function [10], have been suggested to play roles in regulating gene transcription (more than 40 target genes have been reported), DNA replication, chromatin changes during cell cycle and chromatin remodeling [40, 41]. HMGA proteins are expressed abundantly in embryonic, rapidly proliferating, and tumor cells, but they are absent or expressed at very low levels in normal, differentiated cells [10, 42–45]. Many reports indicate that HMGA proteins are oncogenic and contribute to many common diseases [42, 46], including benign and malignant tumors [4, 42], obesity [47], diabetes [48], and atherosclerosis [49]. Recently, blocking HMGA function was suggested for the therapeutic interventions of cancer [4].

HMGB proteins are originally identified as nuclear DNA-binding proteins, which, opposing to the function of histone H1, act primarily as architectural facilitators to regulate gene transcriptions by manipulating nucleoprotein complexes [25, 50, 51] and to fluidize chromatin by loosening the wrapped DNA-core histone complex [2, 52, 53]. The Hmgb1 knockout mice die shortly after birth, supporting the functional significance of HMGB1 [54]. One of the mechanisms for HMGB proteins to control gene transcription is through its direct interaction with nucleosome to loosen the wrapped DNA and to promote its sliding, which facilitates nucleosome remodeling [52, 53]. HMGB proteins can also interact with transcriptional factors, such as NF-κB subunits, p53 and p73, SREBPs (sterol-regulatory element-binding proteins), to regulate gene expression [2, 7, 55]. HMGB1 distinguishes from other HMG proteins in their secretion from macrophages and from necrotic cell and its role as cytokines to mediate the cellular response to infection, injury and inflammation [12, 56]. A growing body of evidence supports that HMGB1 could be released into extracellular environment by immune cells, where it serves as a cytokine mediating the response to infection, injury and inflammation [6, 56, 57].

HMGN proteins do not bind to DNA, rather they bind specifically to nucleosome, between the histone cores and DNA [11]. HMGN proteins are highly dynamic within chromatin [58, 59]. The major members, HMGN1 and HMGN2, are present in the nuclei of all mammalian and most vertebrate cells, and have been studied for more than 30 years. It was demonstrated very recently that HMGN proteins can affect the PTM profile of core histones, indicating that HMGN may play a role in epigenetic regulatory mechanisms [60–62].

PTMs of HMG Proteins

The PTMs of a protein determine/modulate its stability, folding, conformation, distribution, localization, turnover, and interaction with DNA or other proteins. Similar as histones, the biological activities of the HMG proteins are highly regulated by their post-translational modifications, including acetylation, methylation, phosphorylation, and ADP-ribosylation [10]. These secondary biochemical modifications are dynamic and rapidly responsive to intra- and extracellular signaling events. Since different families of HMG proteins have distinct modification profiles, hence different biological implications, next we will discuss separately the PTMs of HMGA, HMGB and HMGN proteins.

PTMs of HMGA Proteins

Phosphorylation

Among all subfamilies of HMG proteins, PTMs of HMGA1 proteins have been extensively studied for more than 20 years. In 1985, which was two years after the original identification of these proteins in Hela cells [63], phosphorylated HMGA1 proteins were detected in Ehrlich ascite cells by the same group [64]. Since then, HMGA1 proteins have been observed to be among the most highly phosphorylated proteins in the nucleus [64, 65]. Further research revealed that HMGA1 proteins could be phosphorylated by several kinases including cdc2 [66, 67], PKC (protein kinase C) [68, 69], protein kinase CK2 (casein kinase II) [70] and HIPK2 (homeodomain-interacting protein kinase-2) [71].

Earlier work by Reeves and coworkers showed that cdc2 could induce the phosphorylation of Thr-52 and Thr-77 in HMGA1a and the phosphorylation resulted in decrease in binding of the protein toward DNA [66, 67]. Our recent study revealed that, other than these two sites, Ser-35 in HMGA1a can also be phosphorylated by cdc2 [72]. In addition, cdc2 can catalyze the phosphorylation of the corresponding Thr-41 and Thr-66 in HMGA1b [72]. Moreover, we showed that HIPK2 could induce the phosphorylation of the same sites, though these two kinases exhibit different site preferences, suggesting that phosphorylation of HMGA1a may be highly regulated, which in turn may control the expression of its target genes [72]. It was also found that the HIPK2- and cdc2-phosphorylated HMGA1a showed much lower binding affinity toward DNA than the unphosphorylated counterpart, which is consistent with the fact that the major phosphorylation sites, i.e., Thr-52 and Thr-77, reside close to the second and third AT-hooks of HMGA1a, respectively [72]. Since all the HIPK2- or cdc2-induced phosphorylation sites precede a proline residue (Ser/Thr-Pro) and reversible phosphorylation of proteins on serine or threonine residues preceding a proline is a major cellular signaling mechanism [73], the conformational change caused by phosphorylation and the following isomerization of the Ser/Thr-Pro peptide bond with Pin1 could affect significantly HMGA1’s activity, such as its interactions with other proteins and/or DNA. In this context, it is also worth noting that Pierantoni et al. [74] recently found that the overexpression of HMGA1 promoted the cytoplasmic relocalization of HIPK2 and the inhibition of the apoptotic function of p53.

The acidic C-terminal tails of HMGA1 proteins are constitutively phosphorylated in vivo. In this regard, protein kinase CK2 catalyzes the phosphorylation of Ser-98, Ser-101 and Ser-102 in HMGA1a and the corresponding sites in HMGA1b (i.e., Ser-87, Ser-90 and Ser-91) both in vitro and in vivo [70, 75–77]. The C-terminal domain of HMGA1 proteins is not directly involved in DNA binding; however, an indirect effect of this phosphorylation on HMGA1’s DNA binding was reported [42, 76, 78]. In contrast, the phosphorylation of HMGA1a at Thr-20, Thr-43 and Thr-63 by protein kinase PKC can attenuate its binding affinity to the promoter regions of PKCγ and neurogranin/RC3 genes [68].

Hyper-phosphorylation in HMGA1a was detected in early apoptotic leukemic cells (HL60, K562, NB4, and U937), which may be related to HMGA1a’s displacement from chromatin, whereas de-phosphorylation occurred during the formation of highly condensed chromatin in apoptotic bodies [78], suggesting a direct link between apoptosis and the degree of phosphorylation in HMGA1a in leukemic cells [78].

It is worth noting that NUCKS (nuclear, casein kinase and cyclin-dependent kinase substrate), a nuclear protein exhibiting considerable similarity to HMGA1 proteins, was also found to be heavily phosphorylated [79].

Acetylation

Other than phosphorylation, HMGA1 proteins are also post-translationally acetylated on a couple of lysine residues in vivo [80–83], and the N-termini of HMGA1a and HMGA1b proteins are constitutively acetylated in vivo [80]. The ordered acetylation of lysine residues in HMGA1 proteins governed the accurate execution of the interferon-β transcriptional switch [84]. In particular, two histone acetyltransferases CBP (CREB-binding protein) and PCAF (p300/CBP-associated factor) were found to be able to catalyze the acetylation of both HMGA1a and HMGA1b [84, 85]. However, the acetylation mediated by these two enzymes has distinct biological outcomes: CBP-acetylated HMGA1a destabilizes the enhanceosome, a higher-order nucleoprotein complex formed in response to virus infection, whereas PCAF-induced acetylation potentiates the gene transcription of interferon-β by stabilizing enhanceosome and preventing HMGA1a from acetylation by CBP. The major acetylation sites induced by CBP and PCAF are Lys-64 and Lys-70, respectively [84, 85].

Our recent study revealed that, other than the previously reported Lys-64 and Lys-70, both PCAF and p300 could acetylate Lys-14, Lys-66 and Lys-73 [83]. Moreover, all the five lysine residues, which could be acetylated by p300 and PCAF in vitro, were also acetylated in PC-3 human prostate cancer cells, though the acetylation profile is different from either p300- or PCAF- induced acetylation, suggesting that both enzymes might be involved in inducing the acetylation of HMGA1 proteins in PC-3 cancer cells [83].

In addition to its function in regulating the transcription of the interferon-β gene, the in-vivo PTM study of HMGA1a in breast cancer cells suggested that acetylation might be related to the different metastatic potential in breast cancer cells [86]. An increased acetylation was observed in HMGA1a from metastatic cells compared to proteins purified from non-metastatic cells.

Methylation

Among the PTMs of HMGA proteins, methylation was the most recently reported [81, 86–89] and it was strictly related to the execution of programmed cell death [87, 88]. In the studied cell systems, including human leukemia, human prostate tumor and rat thyroid transformed cells, only HMGA1a was found to be methylated and the methylation level was increased during apoptosis [88]. In this context, Sgarra et al. [88] reported that the methylation occurs on Arg-25 in the first AT-hook, and later we found that the same site, i.e., Arg-25, can be both mono- and dimethylated in PC-3 human prostate cancer cells. In addition, both isoforms of dimethylation, i.e., symmetric and asymmetric dimethylation, were detected [90]; the asymmetric and symmetric dimethylarginines were assessed by MS/MS based on characteristic neutral losses from the side chains of the modified arginines [90–92].

Unlike phosphorylation and acetylation, where the kinases and acetyltransferases responsible for the corresponding modifications have been extensively examined, exploring the enzymes that induce the methylation of HMGA proteins is emerging as an important field. In this regard, arginine methylation is catalyzed by protein arginine methyltransferases (PRMTs), which are classified into type-I and type-II enzymes. Although both types of enzymes catalyze the formation of ω-NG-monomethylarginine as an intermediate, type-I enzymes induce the formation of asymmetric ω-NG,NG-dimethylarginine, whereas type-II enzymes catalyze the formation of symmetric ω-NG,N’G-dimethylarginine [93]. Recent studies revealed that PRMT6, belonging to the type-I PRMT family, could induce the efficient methylation of HMGA1a both in vitro and in vivo, and the sites of methylation were mapped to be Arg-57 and Arg-59, which are embedded in the second AT-hook [89, 94]. In addition, Arg-83 and Arg-85 could be methylated by PRMT6 to a lower extent than Arg-57 and Arg-59 in the third AT-hook, and a very low level of methylation occurred in the first AT-hook [89].

Since Arg-25 within the first AT-hook seems to be the major methylation site in tumor cells [77, 88, 95], we suspected that other PRMTs could preferentially methylate HMGA1a at Arg-25. It turned out that PRMT1 and PRMT3 showed preference for the methylation of the first AT-hook at Arg-25 and Arg-23 [90]. PRMT3 has less specific methyltransferase activity than PRMT1 and exhibits lower expression levels in nucleus than in cytoplasm. Therefore, PRMT1 is more likely responsible for the methylation of Arg-25 in vivo [90]. However, PRMT1 is a type-I PRMT, which produces the formation of asymmetric ω-NG,NG-dimethylarginine in proteins, whereas both the symmetric and asymmetric dimethylation at Arg-25 were observed [77], suggesting that other PRMTs catalyzing the symmetric dimethylation of HMGA1a may also be involved in the methylation of HMGA1a.

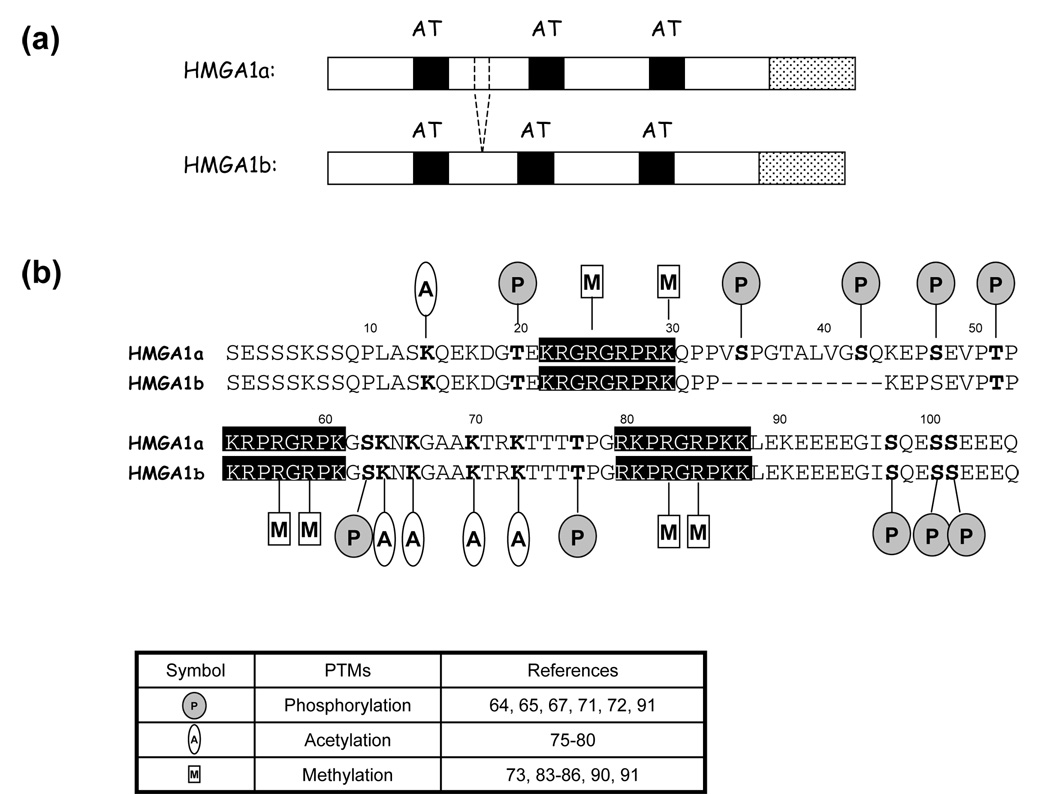

The structure characteristics of human HMGA1 proteins and the residues in these two proteins that were found to be phosphorylated, acetylated and methylated, are summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

(a) Diagrams illustrating the domain structures of HMGA1a and HMGA1b. The three AT-hooks are denoted by dark boxes and the acidic tail is designated by dotted box. (b) Known post-translational modifications of human HMGA1a and HMGA1b proteins, with the modified residues highlighted in bold. The phosphorylation, methylation and acetylation are denoted by shaded circle, open oval and rectangle, respectively. The first methionine is removed post-translationally and not included in the sequence.

PTMs of HMGA Proteins in Cancer Cells

It has been realized for years that the overexpression of HMGA1 proteins is a common feature of human malignant neoplasias of breast [96, 97], prostate [98], colon [99], thyroid [44], lung [100], ovary [101], pancreas [102], gastric [103], etc. Over-expression of HMGA genes can result in the development of different types of cancers, and blockage of their expression suppresses the malignant phenotype, revealing the oncogenic properties of HMGA proteins [104–106]. Thus, suppression of HMGA protein synthesis has been suggested as a potential means for the therapeutic intervention of human malignant neoplasias [105]. However, recent studies also showed that HMGA proteins have a tumor-suppressor role, which is in contrast to their oncogenic properties. One explanation was that HMGA1 proteins might interact with diverse partners depending on the cell type and cellular context, thereby exerting different effects [4]. Given that the binding affinity of HMGA proteins to both DNA and other proteins are highly regulated by their post-translational modifications, we expect that the roles of the PTMs of HMGA proteins in human cancers and corresponding therapeutic strategy will attract increasing attention.

Several studies have suggested that the examination of the PTMs of HMGA proteins may provide valuable information about the physiological and phenotypic state of cancer cells. For example, different types of PTMs of HMGA1 proteins were found in vivo from human breast epithelial cell lines with different stages of neoplastic progression [80, 86]. In particular, HMGA1a proteins present in two derivatives of MCF-7 cells which are moderately (HA7C cells) or highly metastatic (HA8A cells) are more heavily acetylated and methylated than those isolated from the non-metastatic, parental MCF-7 cells [86]. Furthermore, HMGA1a proteins in both the HA7C and HA8A metastatic cell lines, but not in the non-metastatic MCF-7 cells, are dimethylated at specific amino acid residues [86].

For the aforementioned studies, the HMGA proteins were isolated from cancer cell lines, which are immortalized and may not represent the true state of HMGA1 proteins existed in normal somatic cells. Thus, we extended the investigation of the PTMs of HMGA1 proteins to human breast tumor tissues [95]. In this regard, the HMG proteins from two metastatic human breast tumor specimens, three primary tumor tissues and their adjacent normal tissues were isolated and the PTMs of HMGA1 proteins were characterized. It turned out that a more complex pattern of PTMs on HMGA1 proteins was correlated with a more aggressive malignancy in human breast cancer tissues. Novel PTMs, including the methylation at Lys-30 and Lys-54, and the phosphorylation at Ser-43 and Ser-48 were detected in cancer tissues [95]. Additionally, the constitutive phosphorylation in the acidic C-terminal tails of HMGA1 proteins and mono- and di-methylation of Arg-25 in HMGA1a, which were identified previously in those proteins isolated from cancer cell lines, were also present in human breast cancer tissues. Therefore, other than the over-expression of HMGA1 proteins as potential cancer marker for both neoplastic transformation and metastatic progression, the types and sites of PTMs of these proteins may also serve as an important indicator for cancer cells. Nevertheless, more studies need to be conducted to delineate the detailed biological implications of these detected PTMs.

PTMs of HMGB Proteins

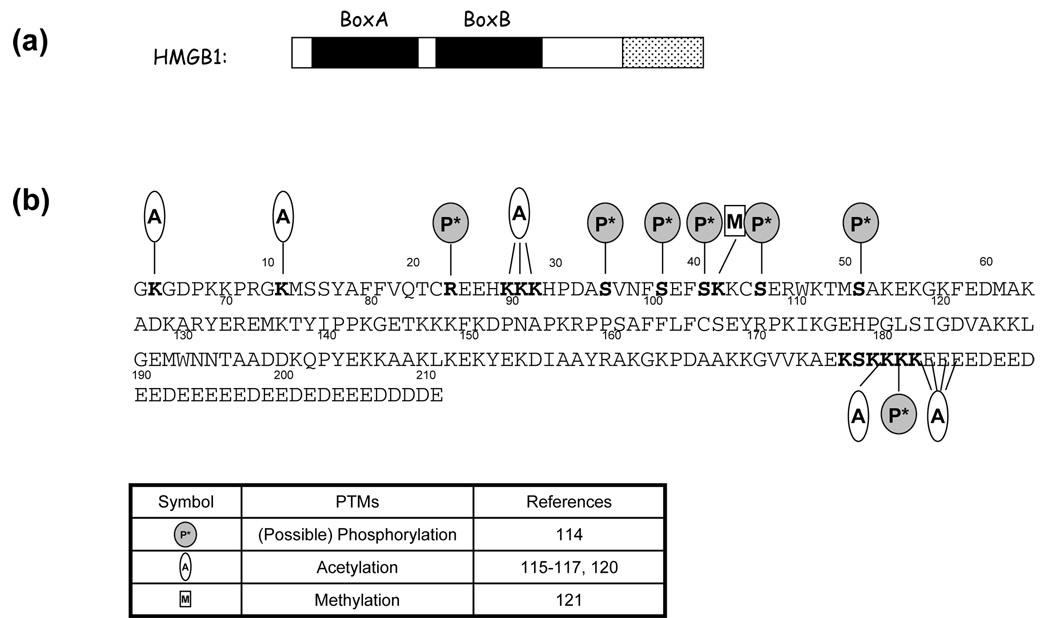

Although the PTMs of HMGB proteins have not been investigated as extensively as those of HMGA1 proteins, accumulating evidence has shown the remarkable biological significances induced by the post-translational acetylation, methylation and phosphorylation of the HMGB1 protein. All the identified PTMs of human HMGB1 are summarized in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

(a) Diagrams illustrating the domain structures of human HMGB1. The two DNA-binding domains (Box A and Box B) are designated by dark boxes and the acidic tail is denoted by a dotted box. (b) Sequences of human HMGB1 showing the post-translational modified residues (in bold). The phosphorylation, methylation and acetylation are denoted by shaded circle, open oval and rectangle, respectively. The first methionine is removed post-translationally and not included in the sequence.

Phosphorylation

Earlier reports demonstrated that HMGB1 and HMGB2, isolated from lamb thymus could be phosphorylated by calcium/phospholipid-dependent protein kinase but not by cAMP-dependent protein kinase [107]. Although only serine residues were phosphorylate in both HMGB1 and HMGB2, a minimum of at least six phosphorylation sites were suggested [107].

Very recently, it was found that HMGB1 was phosphorylated in RAW264.7 cells and human monocytes after treatment with TNF-α or OA (okadaic acid, a phosphatase inhibitor), resulting in the transport of HMGB1 to the cytoplasm for eventual secretion [108]. Even though the phosphorylation sites were not identified in that study, the possible phosphorylation sites were suggested to be Ser-34, Ser-38, Ser-41, Ser-45, Ser-52 and Ser-180, which reside mainly around the two nuclear localization signal regions, namely, NLS1 and NLS2 [108]. Further studies about the exact phosphorylation sites as well as the corresponding kinases involved in this process will provide a better understanding of phosphorylation-controlled nuclear export of HMGB1.

Acetylation

Reversible acetylation of HMGB1 and HMGB2 was first detected in 1979 by Sterner et al. [109] by incubating calf thymus homogenates with 3H-labeled acetate. Automated Edman degradation of intact 3H-labeled HMGB1 revealed that two lysine residues in the N-terminal region of the protein, namely, Lys-2 and Lys-11, were acetylated. Moreover, both HMGB1 and HMGB2 were acetylated/deacetylated by the same enzymes as those acting on histone H4, indicating the roles of histone acetyltransferases (HATs) and histone deacetylases (HDACs) in the dynamic acetylation of HMGB proteins [109]. Further studies revealed that the acetylated HMGB1 protein, isolated from cells grown in the presence of sodium n-butyrate, exhibited significantly enhanced ability to recognize UV light- or cisplatin-damaged DNA and four-way junction, and the modification site was Lys-2 [110]. In addition, it was found that HMGB1 and HMGB2 were in-vitro substrates for CBP, but not for PCAF or Tip60, and the full-length HMGB1 and HMGB2 were monoacetylated at Lys-2 [111]. Removal of the C-terminal acidic tail of HMGB1 resulted in increased acetylation, catalyzed by CBP, at Lys-2 and a novel target site at Lys-81 [111].

Although HMGB1 is located in the nucleus in most cells, recent studies showed that HMGB1 could be either passively leaked out of cells during necrosis [112] or secreted by monocytes and macrophages [113]. Since HMGB1 lacks a secretory signal peptide and doesn’t traverse the ER-Golgi system, the secretion of this nuclear protein seems to require a tightly controlled relocation program [114]. Recently, Bonaldi and coworkers [114] found that, in monocytes and macrophages, HMGB1 can be extensively acetylated so that the protein can be relocated from the nucleus to cytoplasm and eventually for secretion. Forced hyperacetylation of HMGB1 in resting macrophages also caused its relocalization to the cytosol. To locate the acetylated residues, different proteolytic enzymes including trypsin, Glu-C, and Asp-N, alone or in combination, were employed for the digestion, and the resulting peptides were analyzed by MALDI-MS. Totally 17 lysine residues were suggested to be acetylated, among which Lys-27, Lys-28, Lys-29, Lys-179, Lys-181, Lys-182, Lys-183 and Lys-184 were the major acetylated residues, and all of them were within the nuclear localization signal regions [114].

Methylation

In addition to acetylation, mono-methylation of lysine was also identified in HMGB1 isolated from neutrophils, which regulated its relocalization from nucleus to cytoplasm [115]. The methylation site was mapped to be Lys-42, and the methylation led to conformational changes of HMGB1 proteins. Further study demonstrated that most methylated HMGB1 resides in the cytoplasm of neutrophil, whereas un-methylated HMGB1 exists in the nucleus. A possible mechanism for methylation-controlled distribution was that methylation of Lys-42 altered the conformation of box-A, thereby weakening its ability to bind to DNA. Therefore, methylated HMGB1 is distributed in the cytoplasm through passive diffusion from the nucleus [115]. Although HMGB1 was found to be methylated only in neutrophils, we suspect that this is not unique because the cytoplasmic release of HMGB1 also exists in other cells, which could also be controlled by its PTMs, including methylation.

PTMs of HMGB vs Nuclear Export

HMGB1 protein contains two DNA-binding motifs, two nuclear localization signals and two putative nuclear export signals [116], as shown in Figure 2a. Although it has been suggested that post-translational modifications in the HMGB box-domains might regulate finely HMGB1’s biological function in gene transcription, increasing lines of evidence clearly supports that the PTMs of HMGB1 also controlled the shuffle of this protein between the nucleus and cytoplasm [108, 114, 115, 117]. Taking acetylation as an example, deacetylase inhibitors caused the relocalization of HMGB1 from nucleus to the cytoplasm, and mutation of six major acetylation sites to glutamine, which mimics an acetylated lysine, also induced the relocalization of HMGB1 to the cytoplasm, indicating that the subcellular localizations of HMGB1 depend on its acetylation [114]. Methylation of HMGB1 in neutrophils could weaken its binding to DNA, thereby causing its cytoplasmic relocalization in neutrophil through passive diffusion out of the nucleus [115]. Phosphorylation at both NLS sites was shown to be important in blocking the re-entry to the nucleus and in the accumulation in the cytoplasm [108]. However, it is not clear whether one specific modification is dominant, or all the PTMs could play important but different roles in HMGB1’s localization in cytoplasm under physiological conditions.

PTMs of HMGN Proteins

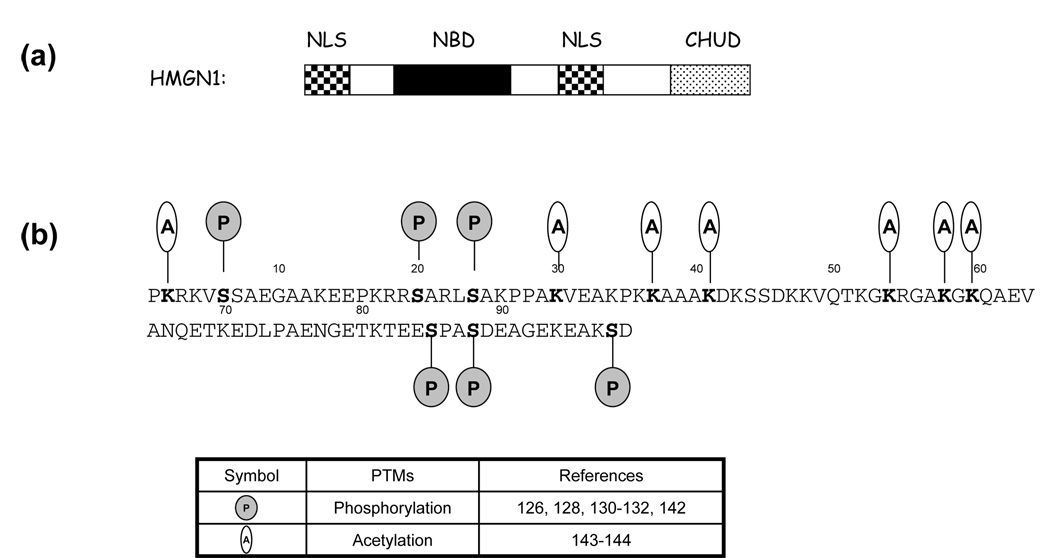

HMGN proteins are the only nuclear proteins that specifically recognize the 147-bp nucleosomal core particle [116, 118] and are present in the nuclei of all mammalian and most vertebrate cells [8]. The NBD domain of HMGN proteins, binding specifically to nucleosome cores, is a highly conserved and positively charged region that is rich in Lys, Arg and Pro residues [11]. PTMs of the HMGN1 protein, including phosphorylation and acetylation [119], are thought to affect the interaction of HMGN1 with its chromatin targets and other proteins, thereby regulating chromatin structure, cellular localization and the cellular response to changing environmental stimuli. All the identified PTMs of human HMGN proteins are summarized in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

(a) The domain structure of human HMGN1. The nucleosome-binding domain (NBD) is denoted by a dark box, two nuclear localization signal (NLS) domains are designated by patterned boxes and the acidic tail is designated by dotted box. (b) The sequence of human HMGN1 showing the post-translational modified residues (in bold) in vivo. The peptide sequences for the three AT-hooks are depicted with black background. The phosphorylation and acetylation are denoted by shaded circle and open oval, respectively. The first methionine is removed post-translationally and not included in the sequence.

Phosphorylation

Like HMGA proteins, phosphorylation of HMGN proteins has been extensively studied over the past 20 years [70, 120–126]. Both HMGN1 and HMGN2 can be phosphorylated in vitro and in vivo, resulting in the decreased interaction of HMGN proteins with the nucleosome [120–123, 127]. However, HMGN1 and HMGN2 are differently phosphorylated during the cell cycle [125, 128], and HMGN2 exhibits much weaker affinity for single-stranded DNA and histone H1 than HMGN1 [121]. Other than preventing the binding to chromatin [127], mitotic phosphorylation of HMGN1 also inhibits nuclear import and promotes interaction with 14.3.3 proteins [129].

Several protein kinases, including PKC [107, 130], cyclic adenosine 3’,5’-monophosphate (cAMP)-dependent protein kinase (PKA) [120, 131], cyclic GMP-dependent protein kinase [132], CK2 [133] and mitogen- and stress-activated kinases (MSKs) [134, 135] can phosphorylate the HMGN1 protein. In this context, Ser-6 and Ser-24 in mammalian HMGN1 are the major and minor sites of phosphorylation catalyzed by cyclic nucleotide-dependent protein kinases [120, 131, 132], whereas Ser-88 and Ser-98 are the major and minor modification sites induced by protein kinase CK2 [133]. In addition, HMGN1 isolated from calf thymus can be phosphorylated in vitro by PKC, and Ser-20 and Ser-24 were proposed to be the potential major and minor phosphorylation sites [130].

MSKs were reported to be the major kinases for the phosphorylation of HMGN1 and histone H3 in response to mitogenic and stress stimuli in mice embryonic fibroblasts, and the phosphorylation sites were located to be at Ser-6 in HMGN1 and Ser-10 in histone H3 [134]. Phosphorylation of HMGN1 leads to a transient weakening of the binding of HMGN1 to chromatin and allows kinases to access histone H3 [62]. Thus, phosphorylation of HMGN1 precedes that of histone H3, suggesting an important role of HMGN1 in modulating the “histone code”.

To examine the phosphorylation of HMGN1 and HMGN2 in vivo, Louie et al. [124] isolated these proteins from K562 human cells treated with phosphatase inhibitor, 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate (TPA) or okadaic acid (OA). Mass spectrometric results revealed that Ser-20 and Ser-24 in HMGN1 were the major and minor phosphorylation sites, respectively, and a third phosphorylation site in HMGN1 was located to be either Ser-6 or Ser-7 [124]. On the other hand, the major and minor sites of phosphorylation in HMGN2 were Ser-24 and Ser-28, respectively. A more recent study by Zou et al. [136] demonstrated that Ser-6, Ser-85, Ser-88, and Ser-98 were phosphorylated in MCF-7 human breast cancer cells. The failure to detect the phosphorylation of Ser-6, Ser-85, Ser-88, and Ser-98 in K562 cells and of Ser-20 and Ser-24 in MCF-7 cells suggested that the phosphorylation of human HMGN1 could be cell line-dependent, though the different sensitivities of the mass spectrometers employed in these studies may also contribute to the observed differences. Moreover, it remains possible that the treatment with phosphatase inhibitors (i.e., TPA and OA) somehow results in the increase in the levels of phosphorylation at Ser-20 and Ser-24 in K562 cells. It is also worth noting that Ser-85 precedes a proline residue, indicating that a praline-directed kinase might be involved in the phosphorylation of this residue.

Acetylation

p300 acetylates both HMGN1 and HMGN2 at multiple lysine residues, which are conserved among all the HMGN family members [137]. There are seven major acetylation sites in HMGN1, in which Lys-2 is located in the NLS region, Lys-30, Lys-37 and Lys-41 are in the nucleosome-binding domain, and Lys-54, Lys-58 and Lys-60 are near or at the second element of the bipartite nuclear localization signals [137]. Six other lysines, namely, Lys-13, Lys-17, Lys-26, Lys-47, Lys-52 and Lys-81, were found to be minor acetylation sites. PCAF, on the other hand, can acetylate HMGN2, mainly at Lys-2, but not HMGN1 [138]. Moreover, all the acetylated HMGNs bind nucleosome less efficiently than unmodified HMGNs [11, 137, 138].

HMGN and Histones

HMGN proteins unfold higher-order chromatin structure by targeting two main elements known to compact chromatin: histone H1 and the amino termini of the core histones [11]. HMGN proteins compete with histone H1 for nucleosome binding sites, suggesting that the local structure of the chromatin fiber is modulated by a dynamic interplay between histone H1 and HMGN [58, 139]. The effects of HMGN proteins on the PTMs of histones H2 and H3 have been recently examined; the presence of HMGN1, but not HMGN2, inhibited the phosphorylation of histone H3 at Ser-10 and Ser-28. In addition, the existence of HMGN1 changed the acetylation and methylation of H3 at Lys-14, whereas that of HMGN2 enhanced H3 acetylation at Lys-14 [60, 62]. Moreover, HMGN1 could modulate the phosphorylation of histone H2A at Ser-1 [61]. On the grounds that the PTMs of HMGN proteins affect their interactions with different targets [11], these findings suggested that “histone code” could be finely regulated by HMGN proteins and their PTMs. Further studies on the dynamic network between HMGN proteins and histone proteins will provide further insights into the molecular mechanisms in the context of chromatin activities.

Conclusions and perspectives

It is now clear that HMG proteins are essential in chromatin dynamics and they influence various DNA processes in the context of chromatin, which include transcription, replication, recombination and repair. Changes in HMG expression levels alter the cellular phenotype and lead to developmental abnormalities and diseases [12]. A large body of experimental evidence, as discussed above, indicates that HMG proteins participate a wide range of cellular activities influenced by their post-translational modifications. Therefore, characterization of these chemical modifications of HMG proteins will provide significant insights into the mechanism of action of these proteins, which may eventually lead to improved detection, therapy and prognosis of human diseases.

The existence of multiple modifications within HMG proteins raises the question: Does HMG behave like histones, in which the unique combinations of post-translational modifications exist? How these multiple modifications or distinct combination set are established or maintained? To this end, further studies need to be conducted to identify the phenotypes of these modifications, either present alone or in combination with other modifications. Furthermore, the identification of enzymes responsible for the corresponding modifications, as well as other regulatory proteins, will provide important information on the mechanism of cellular activities of these proteins.

Acknowledgment

The authors want to thank the National Institutes of Health for supporting this research (Grant No. R01 CA116522).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Bustin M, Reeves R. Prog. Nucleic Acid Res. Mol. Biol. 1996;54:35–100. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(08)60360-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agresti A, Bianchi ME. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2003;13:170–178. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(03)00023-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goodwin GH, Sanders C, Johns EW. Eur. J. Biochem. 1973;38:14–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1973.tb03026.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fusco A, Fedele M. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2007;7:899–910. doi: 10.1038/nrc2271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reeves R, Adair JE. DNA Repair. 2005;4:926–938. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2005.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mantell LL, Parrish WR, Ulloa L. Shock. 2006;25:4–11. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000188710.04777.9e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bianchi ME, Agresti A. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2005;15:496–506. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2005.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bustin M. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1999;19:5237–5246. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.8.5237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thomas JO, Travers AA. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2001;26:167–174. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(01)01801-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reeves R. Gene. 2001;277:63–81. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(01)00689-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bustin M. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2001;26:431–437. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(01)01855-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hock R, Furusawa T, Ueda T, Bustin M. Trends Cell Biol. 2007;17:72–79. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2006.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Travers A. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2000;10:102–109. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(99)00056-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lim JH, Catez F, Birger Y, Postnikov YV, Bustin M. Methods Enzymol. 2004;375:323–342. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(03)75021-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reeves R. Methods Enzymol. 2004;375:297–322. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(03)75020-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reeves R, Nissen MS. Methods Enzymol. 1999;304:155–188. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(99)04011-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bergeron S, Anderson DK, Swanson PC. Methods Enzymol. 2006;408:511–528. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(06)08032-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bustin M. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2001;26:152–153. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)01777-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reeves R, Nissen MS. J. Biol. Chem. 1990;265:8573–8582. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnson KR, Lehn DA, Reeves R. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1989;9:2114–2123. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.5.2114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnson KR, Lehn DA, Elton TS, Barr PJ, Reeves R. J. Biol. Chem. 1988;263:18338–18342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Manfioletti G, Giancotti V, Bandiera A, Buratti E, Sautiere P, Cary P, Crane-Robinson C, Coles B, Goodwin GH. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:6793–6797. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.24.6793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Read CM, Cary PD, Crane-Robinson C, Driscoll PC, Norman DG. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:3427–3436. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.15.3427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weir HM, Kraulis PJ, Hill CS, Raine AR, Laue ED, Thomas JO. EMBO J. 1993;12:1311–1319. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05776.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stros M, Launholt D, Grasser KD. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2007;64:2590–2606. doi: 10.1007/s00018-007-7162-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Birger Y, Ito Y, West KL, Landsman D, Bustin M. DNA Cell Biol. 2001;20:257–264. doi: 10.1089/104454901750232454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hill DA, Pedulla ML, Reeves R. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:2135–2144. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.10.2135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hill DA, Reeves R. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3523–3531. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sessa L, Bianchi ME. Gene. 2007;387:133–140. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2006.08.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Webb M, Thomas JO. J. Mol. Biol. 1999;294:373–387. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Teo SH, Grasser KD, Thomas JO. Eur. J. Biochem. 1995;230:943–950. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1995.tb20640.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Paull TT, Haykinson MJ, Johnson RC. Genes Dev. 1993;7:1521–1534. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.8.1521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bianchi ME, Beltrame M, Paonessa G. Science. 1989;243:1056–1059. doi: 10.1126/science.2922595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hughes EN, Engelsberg BN, Billings PC. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:13520–13527. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pil PM, Lippard SJ. Science. 1992;256:234–237. doi: 10.1126/science.1566071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pasheva EA, Pashev IG, Favre A. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:24730–24736. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.38.24730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hock R, Scheer U, Bustin M. J. Cell Biol. 1998;143:1427–1436. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.6.1427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Trieschmann L, Postnikov YV, Rickers A, Bustin M. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1995;15:6663–6669. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.12.6663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ding HF, Bustin M, Hansen U. Mol.Cell. Biol. 1997;17:5843–5855. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.10.5843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reeves R, Beckerbauer L. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2001;1519:13–29. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(01)00215-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reeves R. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2003;81:185–195. doi: 10.1139/o03-044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sgarra R, Rustighi A, Tessari MA, Di Bernardo J, Altamura S, Fusco A, Manfioletti G, Giancotti V. FEBS Lett. 2004;574:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bandiera A, Bonifacio D, Manfioletti G, Mantovani F, Rustighi A, Zanconati F, Fusco A, Di Bonito L, Giancotti V. Cancer Res. 1998;58:426–431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chiappetta G, Tallini G, De Biasio MC, Manfioletti G, Martinez-Tello FJ, Pentimalli F, de Nigris F, Mastro A, Botti G, Fedele M, Berger N, Santoro M, Giancotti V, Fusco A. Cancer Res. 1998;58:4193–4198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fedele M, Bandiera A, Chiappetta G, Battista S, Viglietto G, Manfioletti G, Casamassimi A, Santoro M, Giancotti V, Fusco A. Cancer Res. 1996;56:1896–1901. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Young AR, Narita M. Genes Dev. 2007;21:1005–1009. doi: 10.1101/gad.1554707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Anand A, Chada K. Nat. Genet. 2000;24:377–380. doi: 10.1038/74207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Foti D, Chiefari E, Fedele M, Iuliano R, Brunetti L, Paonessa F, Manfioletti G, Barbetti F, Brunetti A, Croce CM, Fusco A, Brunetti A. Nat. Med. 2005;11:765–773. doi: 10.1038/nm1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schlueter C, Hauke S, Loeschke S, Wenk HH, Bullerdiek J. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2005;201:101–107. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2004.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Das D, Scovell WM. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:32597–32605. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M011792200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sutrias-Grau M, Bianchi ME, Bernues J. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:1628–1634. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.3.1628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bonaldi T, Langst G, Strohner R, Becker PB, Bianchi ME. EMBO J. 2002;21:6865–6873. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Travers AA. EMBO Rep. 2003;4:131–136. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.embor741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Calogero S, Grassi F, Aguzzi A, Voigtlander T, Ferrier P, Ferrari S, Bianchi ME. Nat. Genet. 1999;22:276–280. doi: 10.1038/10338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Najima Y, Yahagi N, Takeuchi Y, Matsuzaka T, Sekiya M, Nakagawa Y, Amemiya-Kudo M, Okazaki H, Okazaki S, Tamura Y, Iizukac Y, Ohashi K, Harada K, Gotoda T, Nagai R, Kadowaki T, Ishibashi S, Yamada N, Osuga J, Shimano H. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:27523–27532. doi: 10.1074/jbc.m414549200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lotze MT, Tracey KJ. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2005;5:331–342. doi: 10.1038/nri1594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dumitriu IE, Baruah P, Manfredi AA, Bianchi ME, Rovere-Querini P. Trends Immunol. 2005;26:381–387. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2005.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Catez F, Brown DT, Misteli T, Bustin M. EMBO Rep. 2002;3:760–766. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kvf156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Catez F, Lim JH, Hock R, Postnikov YV, Bustin M. Biochem. Cell. Biol. 2003;81:113–122. doi: 10.1139/o03-040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ueda T, Postnikov YV, Bustin M. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:10182–10187. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600821200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Postnikov YV, Belova GI, Lim JH, Bustin M. Biochemistry. 2006;45:15092–15099. doi: 10.1021/bi0613271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lim JH, Catez F, Birger Y, West KL, Prymakowska-Bosak M, Postnikov YV, Bustin M. Mol. Cell. 2004;15:573–584. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lund T, Holtlund J, Fredriksen M, Laland SG. FEBS Lett. 1983;152:163–167. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(83)80370-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lund T, Holtlund J, Laland SG. FEBS Lett. 1985;180:275–279. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(85)81085-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Elton TS, Reeves R. Anal. Biochem. 1986;157:53–62. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(86)90195-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nissen MS, Langan TA, Reeves R. J. Biol. Chem. 1991;266:19945–19952. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Reeves R, Langan TA, Nissen MS. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1991;88:1671–1675. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.5.1671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Xiao DM, Pak JH, Wang X, Sato T, Huang FL, Chen HC, Huang KP. J. Neurochem. 2000;74:392–399. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0740392.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Schwanbeck R, Wisniewski JR. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:27476–27483. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.43.27476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Palvimo J, Linnala-Kankkunen A. FEBS Lett. 1989;257:101–104. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(89)81796-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Pierantoni GM, Fedele M, Pentimalli F, Benvenuto G, Pero R, Viglietto G, Santoro M, Chiariotti L, Fusco A. Oncogene. 2001;20:6132–6141. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zhang Q, Wang Y. J. Proteome Res. 2007;6:4711–4719. doi: 10.1021/pr700571d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lu KP, Liou YC, Zhou XZ. Trends Cell Biol. 2002;12:164–172. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(02)02253-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Pierantoni GM, Rinaldo C, Mottolese M, Di Benedetto A, Esposito F, Soddu S, Fusco A. J. Clin. Invest. 2007;117:693–702. doi: 10.1172/JCI29852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 75.Ferranti P, Malorni A, Marino G, Pucci P, Goodwin GH, Manfioletti G, Giancotti V. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:22486–22489. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wang DZ, Ray P, Boothby M. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:22924–22932. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.39.22924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zou Y, Wang Y. Biochemistry. 2005;44:6293–6301. doi: 10.1021/bi0475525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Diana F, Sgarra R, Manfioletti G, Rustighi A, Poletto D, Sciortino MT, Mastino A, Giancotti V. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:11354–11361. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009521200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ostvold AC, Norum JH, Mathiesen S, Wanvik B, Sefland I, Grundt K. Eur. J. Biochem. 2001;268:2430–2440. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2001.02120.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Banks GC, Li Y, Reeves R. Biochemistry. 2000;39:8333–8346. doi: 10.1021/bi000378+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Edberg DD, Adkins JN, Springer DL, Reeves R. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:8961–8973. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407348200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Jiang X, Wang Y. Biochemistry. 2006;45:7194–7201. doi: 10.1021/bi060504v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Zhang Q, Zhang K, Zou Y, Perna A, Wang Y. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2007;18:1569–1578. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2007.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Munshi N, Agalioti T, Lomvardas S, Merika M, Chen G, Thanos D. Science. 2001;293:1133–1136. doi: 10.1126/science.293.5532.1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Munshi N, Merika M, Yie J, Senger K, Chen G, Thanos D. Mol. Cell. 1998;2:457–467. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80145-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Edberg DD, Bruce JE, Siems WF, Reeves R. Biochemistry. 2004;43:11500–11515. doi: 10.1021/bi049833i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Sgarra R, Diana F, Rustighi A, Manfioletti G, Giancotti V. Cell Death Differ. 2003;10:386–389. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Sgarra R, Diana F, Bellarosa C, Dekleva V, Rustighi A, Toller M, Manfioletti G, Giancotti V. Biochemistry. 2003;42:3575–3585. doi: 10.1021/bi027338l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Sgarra R, Lee J, Tessari MA, Altamura S, Spolaore B, Giancotti V, Bedford MT, Manfioletti G. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:3764–3772. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510231200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Zou Y, Webb K, Perna AD, Zhang Q, Clarke S, Wang Y. Biochemistry. 2007;46:7896–7906. doi: 10.1021/bi6024897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Gehrig PM, Hunziker PE, Zahariev S, Pongor S. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2004;15:142–149. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2003.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Brame CJ, Moran MF, McBroom-Cerajewski LD. Rapid. Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2004;18:877–881. doi: 10.1002/rcm.1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.McBride AE, Silver PA. Cell. 2001;106:5–8. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00423-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Miranda TB, Webb KJ, Edberg DD, Reeves R, Clarke S. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2005;336:831–835. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.08.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Zou Y, Wang Y. J. Proteome Res. 2007;6:2304–2314. doi: 10.1021/pr070072q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Chiappetta G, Botti G, Monaco M, Pasquinelli R, Pentimalli F, Di Bonito M, D'Aiuto G, Fedele M, Iuliano R, Palmieri EA, Pierantoni GM, Giancotti V, Fusco A. Clin. Cancer Res. 2004;10:7637–7644. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Flohr AM, Rogalla P, Bonk U, Puettmann B, Buerger H, Gohla G, Packeisen J, Wosniok W, Loeschke S, Bullerdiek J. Histol. Histopathol. 2003;18:999–1004. doi: 10.14670/HH-18.999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Tamimi Y, van der Poel HG, Denyn MM, Umbas R, Karthaus HF, Debruyne FM, Schalken JA. Cancer Res. 1993;53:5512–5516. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Chiappetta G, Manfioletti G, Pentimalli F, Abe N, Di Bonito M, Vento MT, Giuliano A, Fedele M, Viglietto G, Santoro M, Watanabe T, Giancotti V, Fusco A. Int. J. Cancer. 2001;91:147–151. doi: 10.1002/1097-0215(200002)9999:9999<::aid-ijc1033>3.3.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Sarhadi VK, Wikman H, Salmenkivi K, Kuosma E, Sioris T, Salo J, Karjalainen A, Knuutila S, Anttila S. J. Pathol. 2006;209:206–212. doi: 10.1002/path.1960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Masciullo V, Baldassarre G, Pentimalli F, Berlingieri MT, Boccia A, Chiappetta G, Palazzo J, Manfioletti G, Giancotti V, Viglietto G, Scambia G, Fusco A. Carcinogenesis. 2003;24:1191–1198. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgg075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Abe N, Watanabe T, Masaki T, Mori T, Sugiyama M, Uchimura H, Fujioka Y, Chiappetta G, Fusco A, Atomi Y. Cancer Res. 2000;60:3117–3122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Nam ES, Kim DH, Cho SJ, Chae SW, Kim HY, Kim SM, Han JJ, Shin HS, Park YE. Histopathol. 2003;42:466–471. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.2003.01618.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Berlingieri MT, Pierantoni GM, Giancotti V, Santoro M, Fusco A. Oncogene. 2002;21:2971–2980. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Scala S, Portella G, Fedele M, Chiappetta G, Fusco A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:4256–4261. doi: 10.1073/pnas.070029997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Wood LJ, Maher JF, Bunton TE, Resar LM. Cancer Res. 2000;60:4256–4261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Ramachandran C, Yau P, Bradbury EM, Shyamala G, Yasuda H, Walsh DA. J. Biol. Chem. 1984;259:13495–13503. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Youn JH, Shin JS. J. Immunol. 2006;177:7889–7897. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.11.7889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Sterner R, Vidali G, Allfrey VG. J. Biol. Chem. 1979;254:11577–11583. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Ugrinova I, Pasheva EA, Armengaud J, Pashev IG. Biochemistry. 2001;40:14655–14660. doi: 10.1021/bi0113364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Pasheva E, Sarov M, Bidjekov K, Ugrinova I, Sarg B, Lindner H, Pashev IG. Biochemistry. 2004;43:2935–2940. doi: 10.1021/bi035615y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Scaffidi P, Misteli T, Bianchi ME. Nature. 2002;418:191–195. doi: 10.1038/nature00858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Muller S, Scaffidi P, Degryse B, Bonaldi T, Ronfani L, Agresti A, Beltrame M, Bianchi ME. EMBO J. 2001;20:4337–4340. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.16.4337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Bonaldi T, Talamo F, Scaffidi P, Ferrera D, Porto A, Bachi A, Rubartelli A, Agresti A, Bianchi ME. EMBO J. 2003;22:5551–5560. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Ito I, Fukazawa J, Yoshida M. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:16336–16344. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608467200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Bustin M, Lehn DA, Landsman D. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1990;1049:231–243. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(90)90092-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Gardella S, Andrei C, Ferrera D, Lotti LV, Torrisi MR, Bianchi ME, Rubartelli A. EMBO Rep. 2002;3:995–1001. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kvf198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Sandeen G, Wood WI, Felsenfeld G. Nucleic Acids Res. 1980;8:3757–3778. doi: 10.1093/nar/8.17.3757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Reeves R, Chang D, Chung SC. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1981;78:6704–6708. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.11.6704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Spaulding SW, Fucile NW, Bofinger DP, Sheflin LG. Mol. Endocrinol. 1991;5:42–50. doi: 10.1210/mend-5-1-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Palvimo J, Maenpaa PH. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1988;952:172–180. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(88)90113-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Palvimo J, Linnala-Kankkunen A, Maenpaa PH. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1985;133:343–346. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(85)91881-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Lund T, Berg K. FEBS Lett. 1991;289:113–116. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(91)80921-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Louie DF, Gloor KK, Galasinski SC, Resing KA, Ahn NG. Protein Sci. 2000;9:170–179. doi: 10.1110/ps.9.1.170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Bhorjee JS. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1981;78:6944–6948. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.11.6944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Saffer JD, Glazer RI. J. Biol. Chem. 1982;257:4655–4660. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Prymakowska-Bosak M, Misteli T, Herrera JE, Shirakawa H, Birger Y, Garfield S, Bustin M. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2001;21:5169–5178. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.15.5169-5178.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Lund T, Skalhegg BS, Holtlund J, Blomhoff HK, Laland SG. Eur. J. Biochem. 1987;166:21–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1987.tb13477.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Prymakowska-Bosak M, Hock R, Catez F, Lim JH, Birger Y, Shirakawa H, Lee K, Bustin M. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002;22:6809–6819. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.19.6809-6819.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Palvimo J, Mahonen A, Maenpaa PH. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1987;931:376–383. doi: 10.1016/0167-4889(87)90229-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Walton GM, Spiess J, Gill GN. J. Biol. Chem. 1982;257:4661–4668. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Palvimo J, Linnala-Kankkunen A, Maenpaa PH. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1983;110:378–382. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(83)91159-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Walton GM, Spiess J, Gill GN. J. Biol. Chem. 1985;260:4745–4750. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Soloaga A, Thomson S, Wiggin GR, Rampersaud N, Dyson MH, Hazzalin CA, Mahadevan LC, Arthur JS. EMBO J. 2003;22:2788–2797. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Thomson S, Clayton AL, Hazzalin CA, Rose S, Barratt MJ, Mahadevan LC. EMBO J. 1999;18:4779–4793. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.17.4779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Zou Y, Jiang X, Wang Y. Biochemistry. 2004;43:6322–6329. doi: 10.1021/bi0362828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Bergel M, Herrera JE, Thatcher BJ, Prymakowska-Bosak M, Vassilev A, Nakatani Y, Martin B, Bustin M. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:11514–11520. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.15.11514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Herrera JE, Sakaguchi K, Bergel M, Trieschmann L, Nakatani Y, Bustin M. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1999;19:3466–3473. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.5.3466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Catez F, Yang H, Tracey KJ, Reeves R, Misteli T, Bustin M. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004;24:4321–4328. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.10.4321-4328.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]