Abstract

Small-interfering RNAs (siRNAs) from natural cis-antisense pairs derived from the 3′-coding region of the barley (Hordeum vulgare) CesA6 cellulose synthase gene substantially increase in abundance during leaf elongation. Strand-specific RT-PCR confirmed the presence of an antisense transcript of HvCesA6 that extends ≥1230 bp from the 3′ end of the CesA-coding sequence. The increases in abundance of the CesA6 antisense transcript and the 21-nt and 24-nt siRNAs derived from the transcript are coincident with the down-regulation of primary wall CesAs, several Csl genes, and GT8 glycosyl transferase genes, and are correlated with the reduction in rates of cellulose and (1 → 3),(1 → 4)-β-D-glucan synthesis. Virus induced gene silencing using unique target sequences derived from HvCesA genes attenuated expression not only of the HvCesA6 gene, but also of numerous nontarget Csls and the distantly related GT8 genes and reduced the incorporation of D-14C-Glc into cellulose and into mixed-linkage (1 → 3),(1 → 4)-β-D-glucans of the developing leaves. Unique target sequences for CslF and CslH conversely silenced the same genes and lowered rates of cellulose and (1 → 3),(1 → 4)-β-D-glucan synthesis. Our results indicate that the expression of individual members of the CesA/Csl superfamily and glycosyl transferases share common regulatory control points, and siRNAs from natural cis-antisense pairs derived from the CesA/Csl superfamily could function in this global regulation of cell-wall synthesis.

Keywords: CesA/Csl genes, cis-NAT pairs, RNA regulation, small RNAs, VIGS

Plant cell walls constrain the sizes and shapes of plant cells, establish cell architecture, and are the basis of plant form and stature (1, 2). They are composite structures of cellulose microfibrils interlaced with complex glycans embedded in a physiologically active pectin matrix. The primary wall is a dynamic structure that is expanded as new material is added to accommodate cell growth, whereas thick secondary walls are elaborated in certain cell types during differentiation. Although cellulose microfibrils are the principal scaffold in both primary and secondary walls, genes encoding cellulose synthases (CesAs) are differentially expressed and are coordinately regulated with the production of a great many gene products required for biogenesis of distinct sets of matrix polymers. Over 1,500 genes in Arabidopsis, rice, and maize are currently annotated to possess cell wall-related functions (http://cellwall.genomics.purdue.edu), and we estimate that over 1,000 genes of unknown function are involved in cell wall biogenesis (3). We still have much to learn about the specific functions of the Csls, the hundreds of glycosyl transferase genes and the many classes of other genes that function in wall biogenesis, but also to learn about the regulation of large networks responsible for wall biogenesis at specific stages of development.

In this work, we found naturally occurring small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) derived from the HvCesA6 gene. At late stages of leaf elongation, the levels of these RNAs increase markedly coincident with a decrease in expression of the CesAs, Csls, and an evolutionarily distant GT8 glycosyl transferase gene. The inverse correlation with CesA expression during normal leaf growth suggests that they form natural cis-antisense pairs in this down-regulation and can act in trans on other related Csl transcripts. This down-regulation could constitute a key requisite for the transition to new wall biogenesis programs during differentiation.

Virus-induced gene silencing (VIGS) is a reverse genomic technique to activate a natural sequence-specific RNA degradation system (4), which has been used to silence CesAs in tobacco (Nicotiana benthamiana), resulting in swollen phenotypes and drastic decreases in cellulose content (5). VIGS based on Barley Stripe Mosaic virus (BSMV) has been shown to be an effective means for transient silencing in barley (Hordeum vulgare) and hexaploid wheat (Triticum aestivum) (6, 7), thus providing a means to explore gene function in grasses species, for which the number of cell wall mutants is quite limited (3). However, we describe that VIGS experiments targeted to conserved regions of barley CesAs resulted in enhanced reduction in transcript levels of not only the evolutionarily related CesA and Csl genes, but also of nontarget GT8 genes. Our results, coupled with data from Arabidopsis and rice small RNA databases, indicate that the expression of individual members of the CesA/Csl superfamily and glycosyl transferases share common regulatory control points, and that small interfering RNAs from natural cis-antisense pairs derived from CesAs could function in global regulation.

Results

Detection of Barley CesA6 Antisense Transcripts by Strand-Specific RT-PCR.

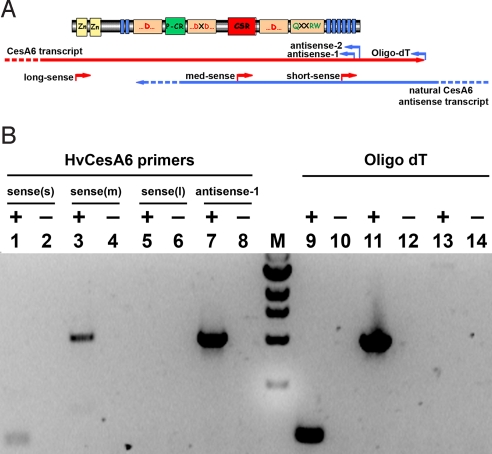

Strand-specific RT-PCR using several different primers specific for the HvCesA6 gene showed the presence of natural antisense transcripts of the HvCesA6 gene (Fig. 1). First-strand cDNAs were synthesized by using either gene-specific sense PCR primers (which anneal only to antisense transcripts), or a gene-specific antisense PCR primer, or oligo dT (which anneal only to sense transcripts). PCR products were detected for short (191 bp) and medium (1,041 bp) length antisense transcripts, but not the long antisense transcript (3,131 bp) (Fig. 1B). Control sense transcripts for all three (short, medium, and long) products by PCR were detected. DNA sequencing of the medium length product confirmed that amplification was from an HvCesA6 antisense transcript. The medium-length PCR product indicates that the natural HvCesA6 antisense sequence extends at least 1,230 bp from the 3′ end of the HvCesA6 coding sequence.

Fig. 1.

Strand-specific RT-PCR of barley third leaf RNA for the detection of HvCesA6 antisense transcripts. (A) Schematic representing the primer names, positions, and strands used for strand-specific RT-PCR of HvCesA6 to detect sense and antisense transcripts. (B) RT-PCR was performed with first-strand cDNA templates. For Lanes 1-6, short (s), medium (m), and long (l) A6 sense primers were used to detect antisense transcripts, and either A6-antisense-1 or A6-antisense-2 was used as the primer pair in PCR. For Lanes 7 and 8, A6-antisense-1 was used to detect sense transcript, and A6-sense-(m) was used as the primer pair in PCR. For Lanes 9-14, oligodT was used to detect sense transcripts, by using the three A6-sense primers for PCR. A 1-kb ladder (New England Biolabs) is indicated by (M). The inclusion or exclusion of reverse-trancriptase (RT) is indicated by + or −, respectively. Digital photograph of the ethidium bromide-stained gel is shown in inverted contrast for clarity. Identity of the PCR products was confirmed by DNA sequencing.

Expression of Primary Wall CesAs is Negatively Correlated with HvCesA6-Derived nat-siRNAs and Antisense Transcripts.

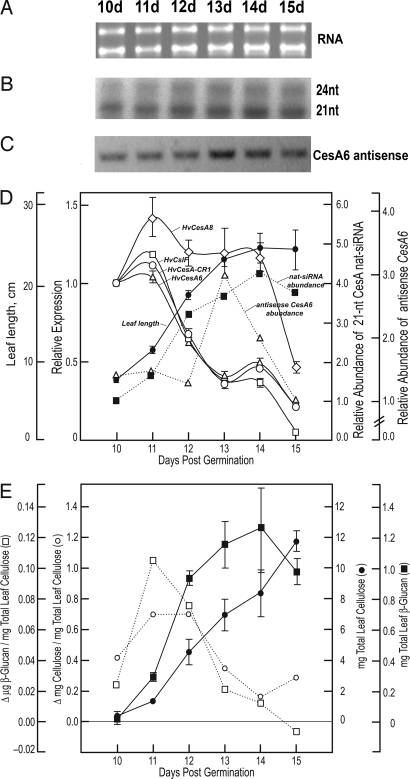

CesA6 antisense transcripts and nat-siRNAs derived from them were assayed with respect to relative rates of cellulose and (1 → 3),(1 → 4)-β-D-glucan (β-glucan) biosynthesis from the emergence of the third leaf from the sheath to the cessation of elongation 5 days later (Fig. 2). By using the short HvCesA6 sense riboprobe (Fig. 3A), ribonuclease protection assays showed a significant increase in the abundance of the nat-siRNA protected fragments during third leaf development (Fig. 2 B and D). Comparative quantitative real-time (qRT-) PCR showed that transcript levels of HvCesA1, HvCesA6, HvCesA8, and HvCslF6 (formerly HvCslF1) all peaked at 11 days and decreased in a biphasic manner (Fig. 2D). The amounts of the nat-siRNAs and antisense transcript generally increased during leaf development, then tapered markedly by day 15 (Fig. 2 B–D). The relative rates of synthesis of both cellulose and the β-glucans was highest during the early stages of leaf elongation and began to decrease between days 11 and 12, and were well correlated with the relative expression levels of genes involved in primary wall synthesis (Fig. 2 D and E). The expression of secondary cell wall-associated HvCesA8 gene remained relatively high during the elongation phase of the third leaf and then abruptly fell (Fig. 2D).

Fig. 2.

CesA antisense small RNAs correlate negatively with primary cell wall CesA gene expression and rates of cellulose and β-glucan biosynthesis. (A) RNA quantity and quality was verified by agarose gel electrophoresis. (B) Ribonuclease protection assays were performed by using the short HvCesA6 sense probe. (C) Strand-specific RT-PCR was performed with A6-sense-(m) and A6-antisense-1 primers on cDNA synthesized from the time-course RNA by using sense primer A6-sense-(m). Digital photograph of the ethidium bromide-stained gel is shown in inverted contrast for clarity. (D) Comparative quantitative real-time PCR of developing barley third leaves was performed to determine the expression relative to day 10 of several putative primary cell wall CesA genes (HvCesA1 and HvCesA6), a putative secondary cell wall CesA gene (HvCesA8), and the HvCslH1 and HvCslF6 genes. Overlaid are the average leaf blade lengths (cm) ± SD. Ubiquitin10 expression was used as the normalizing target and BSMV/V-PDS (BSMV/PDS4as) as the calibrator (35). Values are the average ± SD of 3–5 biological replicates and are relative to plants infected with empty vector-PDS control plants. Error bars not shown are within the limits of the symbol. Amounts of the 21-nt small RNA, with expression relative to day 10, were quantified by densitometry. (E) Total accumulation and relative rates of cellulose biosynthesis are expressed as the average wt. recovery (mg) ± SD. Values for amounts and relative rates of β-glucan synthesis are mean of 2 replicates.

Fig. 3.

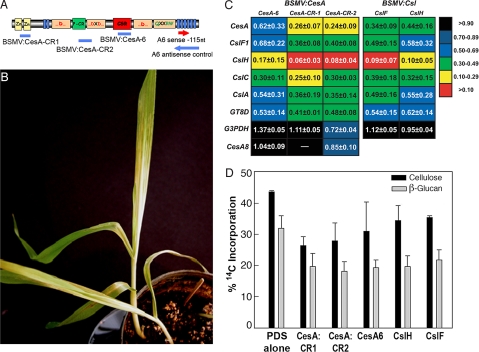

VIGS of the CesA gene superfamily in barley. (A) Schematic indicating the protein domains encoded by CesA mRNAs (28). Blue bands indicate the regions of the CesA cloned into the VIGS constructs used in these experiments. VIGS fragments were designed to silence the CesA gene family as well as the HvCesA6 gene. Red and blue arrows indicate the directional sequence used for sense and antisense riboprobe synthesis, respectively. (B) Onset of silencing is detected by photobleaching as a result of the cosilencing of phytoene desaturase. (C) Silencing of CesAs, CslHs, and CslFs by VIGS results in a global reduction in the expression of genes involved in cell wall biosynthesis. Expressions of CesA6, Csl, GT-8D, and G3PDH genes in plants infected with respective VIGS constructs, assayed by comparative qRT-PCR, are the mean ± SD of 3–5 biological replicates, are relative to plants infected with empty vector-PDS control plants, and are normalized to ubiquitin10 gene expression. (D) Incorporation of D-14C-Glc into cellulose and β-glucan are a percentage of the total radioactivity of each cell wall polymer ± SD of 3 biological replicates.

Suppression of CesA Genes in Barley by VIGS.

VIGS experiments were designed and performed in barley for silencing of all CesA genes as well as a single CesA isoform. To silence the expression of all CesA gene family members, regions within the N-terminal zinc finger motif and part of the plant-conserved region just upstream of the “DxD” motif were cloned into the BSMV-γ RNA vector (Fig. 3A). A VIGS fragment was also designed to specifically target within the “class-specific region” (CSR; ref 8) of an HvCesA6 gene, the closest ortholog of the Arabidopsis and rice primary wall CesA1.

The first leaf of barley plants was infected with the CesA silencing constructs and grown until the onset of VIGS. All VIGS plants, including controls, were coinoculated with a phytoene desaturase silencing construct (BSMV:PDS) to serve as a visual marker of gene silencing. Plants inoculated with VIGS constructs began to show strong photobleaching because of silencing of the phytoene desaturase ∼6–7 days postinoculation in both the second and third leaf, and the broad sectors showing photobleaching were taken for analyses of expression and cell wall synthesis (Fig. 3B). The growth of the second and third leaves was similar after inoculation and systemic infection by any of the BSMV constructs, although a slight decrease was observed during the latter days of growth compared to those of uninoculated or mock-inoculated control plants [see supporting information (SI) Fig. S1].

VIGS of CesAs Reduces the Expression of Target Genes as well as Other Cell Wall Biosynthetic Genes.

Transcript abundance was measured by comparative qRT-PCR by using SYBR green (7). Compared to BSMV:PDS control plants, the expression of CesA genes were substantially reduced in BSMV/CesA infected plants (Fig. 3C). Further, VIGS constructs targeting the entire CesA gene family (CesA-CR1 and CesA-CR2) showed a more pronounced reduction in total CesA expression than did the CesA-6 construct, which targets a sequence unique to the HvCesA6 isoform (Fig. 3C).

To assess the effects of CesA VIGS in barley on the expression of related, nontarget genes, we performed comparative qRT-PCR. We found that the expression levels of several Csl genes were also significantly reduced in CesA VIGS plants (Fig. 3C). Further, the expression of the distantly related but coordinately regulated GT8 genes was also reduced, suggesting that the reductions are not a result of cross-suppression (Fig. 2D), but rather the expression of several related and unrelated cell wall biosynthetic gene families are linked with that of cellulose synthase. A secondary wall CesA8 gene whose expression is not linked with that of the primary wall genes (Fig. 2D), was relatively unaffected by VIGS (Fig. 3C). Also, expression of a metabolic housekeeping gene exhibited either slightly reduced or increased expression relative to BSMV:PDS controls, but differences were much smaller than those observed for cell wall-related genes (Fig. 3C).

VIGS of CesAs Lowers Rates of Cellulose and β-Glucan Synthesis.

Incorporation of 14C-D-Glc into cellulose was substantially lower after silencing with BSMV/CesA-PDS constructs than with BSMV:PDS alone (Fig. 3D). Rates of cellulose synthesis were more strongly suppressed in plants in which the entire CesA gene family was targeted for silencing than when the single CesA6 gene alone was silenced, consistent with expression analyses. Despite the effort to specifically silence CesA, the incorporation of 14C-D-Glc into β-glucan was also markedly lowered in the CesA silenced plants (Fig. 3D). The expression of HvCslF6 gene, whose ortholog in rice was previously demonstrated to encode a factor involved in mixed-linkage β-glucan biosynthesis (9), was also reduced in these plants, possibly explaining the reductions in β-glucan biosynthesis (Fig. 3D). Plants silenced with unique targets from the CslF and CslH gene families also had reduced incorporation of D-14C-Glc into leaf cellulose and mixed-linkage β-glucan (Fig. 3D).

Isoxaben and 2,6-Dichlorobenzonitrile Alter Cellulose Biosynthesis via a Different Mechanism than VIGS.

Two specific inhibitors of cellulose biosynthesis, 2,6-dichlorobenzonitrile (DCB) and isoxaben, inhibited cellulose synthesis within 3–6 h after spraying to levels similar to those exhibited by the VIGS plants (Fig. S2A). Comparative quantitative PCR was performed under the same conditions used for the VIGS plants. In contrast to CesA or Csl VIGS, the expression of CesA genes was relatively unaltered, and CslFs, CslHs, and CslCs were instead up-regulated by DCB or isoxaben (Fig. S2B). These data indicate that the alterations in expression of Csl and GT8 genes as a result of CesA VIGS are not a result of the reduction of cellulose biosynthesis.

Detection of Antisense siRNAs for the CesA Gene Family by Ribonuclease Protection Assay.

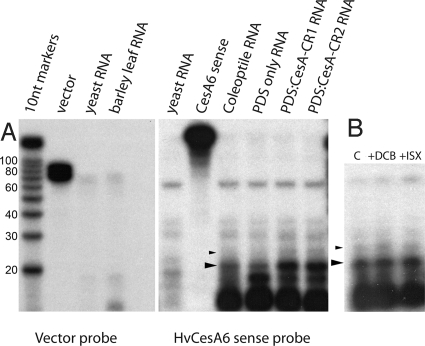

The experiments with DCB and isoxaben inhibition of cellulose synthesis showed that lowering cellulose content does not induce broad suppression of CesA and Csl transcription (Fig. S2B). Although there are no published reports of transitive silencing of endogenous genes, we hypothesized that the VIGS of CesA genes had spread to other nontarget regions by the generation of secondary siRNAs not part of the original VIGS target. Ribonuclease protection assays using the “HvCesA6 sense probe” (214 nt) protected fragments of approximately 21 nt and 24 nt in barley leaf and coleoptile RNA, and the amounts of these were enhanced in leaves infected with BSMV:PDS-CesA-CR1 and BSMV:PDS-CesA-CR2, suggesting that the production of the naturally occurring siRNA(s) was enhanced by CesA VIGS (Fig. 4A). A negative control probe consisting of only the vector portion of the probe (“vector probe”, 99 nt) did not protect any of these fragments, demonstrating that the small RNAs are naturally occurring and arise from a CesA antisense transcript (nat-siRNA). Treatment of barley plants with DCB or isoxaben did not alter levels of either the 21-nt or 24-nt nat-siRNAs (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Detection of CesA antisense siRNAs by ribonuclease protection assay. (A) Ribonuclease protection assays performed with the short HvCesA6 sense probe were hybridized with 10 μg yeast RNA (negative control), A6-sense (probe-only, no RNase control), coleoptile RNA (10 μg), PDS-only (10 μg Vector-PDS VIGS RNA), PDS-CesA-CR1 (10 μg CesA-CR1 VIGS RNA), and PDS-CesA-CR2 (10 μg CesA-CR2 VIGS RNA). The vector-only probe [vector; probe-only controls without RNase were hybridized with 10-μg yeast RNA (negative control) and barley leaf (10-μg barley third leaf RNA). (B) Protection assays were also performed with the short HvCesA6 sense probe hybridized with barley third leaf RNA (10 μg each) treated with Mock buffer (C), 100-μM DCB (+DCB), or 1-μM isoxaben (+ISX). Decade markers (Ambion) were electrophoresed as size standards and are to scale for both (A) and (B). Large arrowheads denote 21-nt RPA fragments, and the small arrowheads denote the 24-nt RPA fragments. Marker lanes are in 10-nt increments beginning with 20 nt.

Discussion

Whereas we are beginning to learn how certain transcription factors specify developmental programs and positively regulate their gene networks, we know very little about how negative regulation of previous programs is coordinated with up-regulation of a new network. Transcriptional switches for programs involving different cell wall gene networks involving a switch from primary to secondary wall include both NAC-domain (10) and Myb transcription factors (11). The lack of secondary wall formation but not cellular specification when these and other NAC-domain containing proteins are repressed and the induction of ectopic secondary walls in overexpressing lines provide strong evidence for control of cell wall gene networks (10). In all eukaryotes, microRNAs (miRNAs), made from noncoding stem-loop transcripts, are processed to form 20–24-nt RNAs that target coding transcripts for elimination (12). From the studies conducted thus far, a majority of the targets of miRNAs are transcription factors, including NAC and Myb proteins (13). Regulation of leaf identity by an APETALA2-like gene, called Glossy15, maintains juvenile identity, whereas the miRNA miR172 down-regulates glossy15 expression to promote transition to the adult state (14), a transition that involves drastic changes in wall architecture.

As cellulose is a major scaffold polymer in plant cell walls, it should not be surprising that coordinate expression of an entire gene network is regulated around the expression of specific cellulose synthases. Multiple CesAs, each thought to interact within heterotrimeric cellulose synthase complexes specific to primary or secondary walls (15), are coordinately expressed in maize, rice, barley, and poplar (16). Expression profiling of Arabidopsis during the transition from primary wall synthesis to vascular differentiation reveal several cell wall-related genes are coexpressed with the secondary wall cellulose synthases (17). The finding that VIGS of the CesA/Csl targets also silences GT8 (Fig. 3C) indicates that coordinately up-regulated genes at one stage of development are coordinately down-regulated at another. Evidence for this comes directly from Milioni et al. (18) who showed by cDNA-AFLP analysis that induction of tracheary element formation in isolated Zinnia cells is accompanied by staged appearance and disappearance of several hundreds of genes. The expression of secondary cell wall-associated HvCesA8 gene remained relatively high during the elongation phase of the third leaf, and the significant sequence identity in much of the 3′ coding region of the gene makes it unlikely to be immune to silencing by either CesA nat-siRNAs or VIGS. However, the expanding leaf contains a spectrum of cell types making primary and secondary walls throughout elongation. Secondary wall cellulose synthesis is confined primarily to tracheids, fiber cells, and epidermal cells, and these cells are isolated from the virus, whose movement in vascular tissue is generally confined to the phloem.

A role for regulation of downstream transcripts of the individual members of the gene network by natural antisense siRNAs (nat-siRNAs) in this regulation is emerging (19). Our data indicate that the down-regulation of CesA/Csls involves nat-siRNAs generated by the cleavage of dsRNA natural antisense precursors. Curiously, the same antisense RNAs are enhanced by VIGS. Although the predominant CesA nat-siRNA is 21 nt, both 21-nt and 24-nt nat-siRNA species were detected. Borsani et al. (20) observed a 24-nt nat-siRNA that sets the position for the phased cleavage of 21-nt small RNAs in response to salt stress, and more recently, nat-siRNAs are implicated in bacterial resistance in Arabidopsis (21). This study reports a potential role of siRNAs in a natural developmental program. Bidirectional transcription from cis-NAT pairs to form dsRNAs that are processed into 21-nt siRNAs has now been observed in Drosophila (22, 23) and mouse (24).

Our data indicate that the generation of dsRNA by VIGS of the CesA genes interferes with a natural antisense control mechanism. The v-siRNAs generated by the RNAi silencing complex could serve as primers for RdRP to generate secondary siRNAs that might account for apparent cross-suppression observed here, noting that RdRP can transcribe bidirectionally in plants (25). However, we found that antisense siRNAs were naturally present in developing leaf and coleoptile tissues, opening the possibility for the production of other multiple small RNAs each having separate subsets of genes to control cell wall biosynthesis via transitivity (26, 27). Transitive silencing by VIGS is thought to only occur in transgenes (25), but this has not been exhaustively examined with a broad range of genes. Whereas our data demonstrate a role for CesA derived nat-siRNAs in the coordinated transition from primary to secondary cell wall expression programs, other functions may exist as well. For instance, CesA small RNAs might mediate the balanced coexpression of the multiple isoforms of CesA associated with primary or secondary cellulose formation. Such a mechanism could explain the difficulties associated with attempts to increase protein levels by overexpression of CesAs (28).

From examination of rice tiling arrays, 23.8% of rice genes exhibit antisense expression (29). Massively parallel signature sequencing (MPSS) of both rice and Arabidopsis transcripts show a considerable number of sequence tags derived from the noncoding strand of CesA and Csl genes, indicating natural antisense transcription in both grasses and dicots. Both MPSS and 454 sequencing have also detected unique small RNAs targeting CesA genes (http://mpss.udel.edu; http://sundarlab.ucdavis.edu/), and Lu et al. (30) also report a miRNA that derives from a natural cis-antisense pair involving CesA. Further, a related GT-2 family member encoding hyaluronan synthase has been demonstrated to be regulated by natural antisense expression, suggesting a conserved mechanism for regulation of Family 2 glycosyl transferases (31).

Henz et al. (19) found that 7.4% of Arabidopsis genes comprise overlapping natural cis-antisense transcripts (cis-NATs) and that frequency of anti-correlated expression is higher than expected in a small number of cis-NAT pairs. We examined the occurrence of cis-NATs among the CesA, Csl, and GT8 genes of Arabidopsis and rice and compared their occurrence with the frequency of antisense RNAs found in above databases. Six of the ten Arabidopsis CesA genes have overlapping pairs of genes, including five of the six CesA genes shown to be coordinately expressed during both primary wall and secondary wall formation (Table S1). Only AtCesA6 had no overlapping gene. In general, the cis-NAT pairs also exhibited a higher hit frequency of antisense RNAs, with several annotated as having sequence identities with other AtCesAs, including AtCesA6 and AtCslD3.

In rice, a single cis-NAT was found among the ten annotated CesAs (Table S2). The Csl genes existed in far fewer cis-NAT pairs, but with the exception of CslC, all had at least 1 pair (Tables S3 and S4). We find significant sequence identity among CesA and Csl genes of rice, including 4 runs of >20 identical nucleotides between a CesA and a CslF (Fig. S3), and numerous additional stretches of identity with only 1–3 mismatches among many CesA-Csl combinations, including CslA, that is most distant from CesA. With few exceptions, the Csls have small RNAs annotated in MPSS tag collections. Notably, a CslD5 is a cis-NAT pair with GATL-5, a Group C GT8. Of the 5 groups of GT8 genes, no cis-NAT pairs are observed for GT8-A or GT8-E, but are represented well in Groups B–D, including the GT8-C (GATL5) with CslD3, and GT8-D with a nuclear transport factor (Table S3). It will be a challenge to assemble the pathways for the spread of silencing by developmentally regulated trans-acting nat-siRNAs, but there is a growing body of public data to support its existence (32).

We were unable detect siRNAs for the barley GT8 gene by ribonuclease-protection assay, suggesting that the coordinated reduction, both natural and VIGS-induced, occurs via another mechanism (Fig. S4). Also, we did not detect 21-nt HvCesA6 nat-siRNAs upstream of the VIGS site suggesting that these nat-siRNAs are confined to the 3′-coding region of the CesA6 gene (Fig. S4). However, we observed protected bands of 24 nt and 30 nt, the significance of these is not yet understood.

Like the Csls, the absence of a cis-NAT pair does not preclude the detection of small RNAs in the MPSS screen, with MPSS tags detected in almost all of them, including sequence identities among the rice GAUT and GATL genes of GT8 (Table S4). How these antisense sequences are generated in the genes that do not comprise a cis-NAT pair is not known, but 2 possibilities are that noncoding antisense RNAs are driven by cryptic promoters or trans-acting small RNAs cleaved from related cis-NAT pairs spread silencing. Precedence for this type of cascade mechanism has been established in Arabidopsis initiated by a miRNA (33). A GT8 ortholog to Arabidopsis GAUT1 has no cis-NAT partner but has three hits in the MPSS database, including a sequence that matches 80 others.

Plants form cell walls that are dynamic structures of cellulose, crosslinking glycans, and various matrix polysaccharides, proteins, and phenolic substances that are reconstructed during embryogenesis, cell enlargement, and cell specification and differentiation. These transitions require not only a positive regulation of new cell wall gene networks, but also the coordinated silencing of the previous networks. siRNAs generated from antisense transcripts of CesAs could represent an initiator of a cascade of cis- and trans-acting silencers of cell-wall gene networks integral to differentiation.

Methods

Plant Growth Conditions—Hordeum vulgare cv.

Black Hulless plants were grown ≤15 d as described (7), with VIGS inoculations at 6 or 7 d. Specific conditions are described in SI Methods. Coleoptiles were from caryopses soaked and germinated in wet filter paper and incubated 2.5 d in darkness, as described (34).

Extraction of RNA and First-Strand cDNA Synthesis.

Total barley leaf and coleoptile RNA was extracted from 100–250 mg tissue by using TriZol reagent (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer's protocol, quantified by A260. Before RT-PCR, genomic DNA contamination was removed from total RNA (10 μg) by Turbo DNA-free DNase treatment (Ambion). The RNA samples were assayed for quality and quantity by agarose gel electrophoresis. First strand cDNA was synthesized from total RNA (1 μg per reaction) by using iScript first strand cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad) and subsequently diluted (1:5) with nuclease-free water.

Detection of Antisense Transcripts by Strand-Specific RT-PCR.

First-strand cDNA was synthesized from 1.7 μg total RNA extracted from late-expanded barley third leaves with the SuperScript III kit (Invitrogen), by using oligo dT as well as the gene-specific primers representative of short, medium, and long sense and antisense primers and subjected to PCR by using the primer-pair combinations and cycle conditions described in SI Methods.

Detection of siRNAs by Ribonuclease Protection Assays (RPA).

Primers were designed for cloning a 465-bp fragment from the 3′-end of the HvCesA6 coding region, and the fragment was amplified by RT-PCR from cDNA prepared from barley third-leaf RNA. The PCR product was sequenced and then cloned into the pGEM-T easy vector kit (Promega). α-32P-UTP (Amersham) radiolabeled probes were prepared from linearized plasmid templates having 5′ overhanging ends, with either T7 or SP6 RNA polymerase by using the MAXIscript Kit (Ambion) to produce the HvCesA6 antisense riboprobe (522 nt) and the HvCesA6 sense riboprobe (214 nt), respectively. Vector sense probe (99 nt) representing the pGEM-T easy vector was prepared as a negative control. Primer design is described in SI Methods.

Ribonuclease protection assays were performed by using the RPAIII kit (Ambion). Labeled riboprobes were gel-purified and hybridized with 10–20 μg total RNA from either barley, yeast, or mouse for 16–18 h at 42 °C. Reaction mixtures were digested with RNase A/T1 (1:100) for 30 min at 37 °C, then stopped with inactivation buffer (Ambion), and protected fragments were precipitated by using 10-μg yeast RNA as a carrier. The protected fragments were separated by 12.5% PAGE. The protected HvCesA6 nat-siRNAs were reproduced across ≥3 independent protection assays.

Measurement of Gene Expression by qRT-PCR.

Primer sets were designed within consensus regions to measure the expression of as many gene family members as possible in uninfected and VIGS-treated plants (Table S5). Reactions using the iTaq SYBR reagent kit (Bio-Rad) were performed in quadruplicate. Standard curves covering 3 orders of magnitude, and no-template controls were performed in triplicate for each primer set. Relative gene expression of VIGS plants and controls from 3–5 separate third-leaf samples was assessed by qRT-PCR using ubiquitin10 expression as the normalizing target and BSMV/V-PDS (BSMV/PDS4as) as a calibrator (35). Ubiquitin10 was deemed optimal after survey of 4 housekeeping gene candidates (data not shown; primers are listed in Table S5). Thermocycle conditions are described in SI Methods.

Design and Construction of BSMV Vectors for CesA/Csl VIGS.

Targets for the specific suppression of the barley CesA, CslF, and CslH gene families were first designed by aligning full-length rice cDNA sequences of each gene family member using Clustal W (36). Targets were selected based on at least 85% nucleotide similarity and at least one 21-nt stretch of 100% nucleotide identity, and the lack of these criteria in nontarget genes. Potential VIGS target sequences garnered from rice were then aligned with available barley CesA and Csl EST sequences to identify the homologous regions, verify desired specificity, and design primers for cloning (as described in SI Methods).

For in vitro transcription of VIGS plasmids, capped viral RNAs were prepared from linearized plasmids by using the mMessage mMachine T7 in vitro transcription kit (Ambion). Plasmid linearization and in vitro transcription was monitored by agarose gel electrophoresis.

Viral Inoculation of Barley Plants.

Plant inoculations were carried out as described previously (7). Briefly, in vitro transcripts of the pBSMV/α, pBSMV/β, pBSMV/γ-PDSas, and the appropriate experimental gene silencing construct (either BSMV/γ, BSMV/γ-CslH-as, BSMV/γ-CslF-s, BSMV/γ-CesA-CR1-s, BSMV/γ-CesA-CR2-s, or BSMV/γ-CesA-6-as) were combined in a 1:1:0.5:0.5 ratio by volume, respectively. For plant inoculations, 3 μl of the mixture of α, β, γ-PDS, and respective γ-RNA transcripts were added to 22.5 μl of FES (37) and applied to 6–7-day-old seedlings by rub-inoculating the first leaf of each plant 2–3 times. The γ-PDSas transcripts were coinoculated with all plants to serve as a visual marker for gene silencing, evident in the third leaves 6–7 d later.

In vivo Labeling of Barley Leaves with [U-14C]-Glucose and Cell-Wall Characterization.

For the developmental time courses and experiments with cellulose synthesis inhibitors, plants were pulse-labeled with 14CO2, liberated by adding a few drops of 1 M H2SO4 to a dish containing 10 μCi per plant of NaH14CO3 (aq) (2.04 GBq mmol−1; MP Biomedicals) in a sealed Plexiglas chamber. The plants were incubated in the presence of the radiolabel under fluorescent lighting for 1 h. The third leaves for each treatment were pooled and harvested into liquid nitrogen. For inhibitor experiments, barley seedlings were grown 11 d in a growth chamber, as described above, and 12 plants each were sprayed (≈5 ml/plant) with 0.1% (vol/vol) Tween 20 (aq) and 0.1% (vol/vol) DMSO containing either no inhibitor (mock), 1 μM isoxaben, or 100 μM DCB. Plants were incubated under fluorescent lights for 3–6 h at ambient temp before labeling as described above.

For VIGS experiments, expanding third leaves of plants (3–5 each) were harvested under 0.01% (vol/vol) Tween 20 (aq) and pulse labeled in vivo with D-[U-14C]-glucose (Amersham Pharmacia) for 2–3 h at ambient temp under fluorescent lights. Labeled leaf tissue was collected into liquid nitrogen from which cell walls were prepared as described earlier (38).

Cellulose and (1 → 3),(1 → 4)-β-Glucan Determination.

The ability to incorporate radiolabeled carbon into cellulose from isolated walls (38) was assayed by acetic-nitric hydrolysis (39), and β-glucan was determined after hydrolysis with a B. subtilis endo-β-D-glucanase, which specifically cleaves a β-(1 → 4)-linkage, only if it is preceded by a β-(1 → 3) linkage (40), as described previously (41). Both methods are described in detail in SI Methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank Dr. Federica Brandizzi for helpful discussions. This work was supported by Grant DE-FG02-05ER15654 from the U.S. Department of Energy, Energy Biosciences. This is article No. 2007-18,250 of the Purdue University Agricultural Experiment Station.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0809408105/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.McCann MC, Roberts K. Architecture of the primary cell wall. In: Lloyd CW, editor. The Cytoskeletal Basis of Plant Growth and Form. New York: Academic; 1991. pp. 109–129. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carpita NC, Gibeaut DM. Structural models of primary cell walls in flowering plants: Consistency of molecular structure with the physical properties of the walls during growth. Plant J. 1993;3:1–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313x.1993.tb00007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yong W, et al. Genomics of plant cell wall biogenesis. Planta. 2005;221:747–751. doi: 10.1007/s00425-005-1563-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ruiz MT, Voinnet O, Baulcombe DC. Initiation and maintenance of virus-induced gene silencing. Plant Cell. 1998;10:937–946. doi: 10.1105/tpc.10.6.937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burton RA, et al. Virus-induced silencing of a plant cellulose synthase gene. Plant Cell. 2000;12:671–705. doi: 10.1105/tpc.12.5.691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holzberg S, Brosio P, Gross C, Pogue GP. Barley stripe mosaic virus-induced gene silencing in a monocot plant. Plant J. 2002;30:315–327. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2002.01291.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scofield SR, Huang L, Brandt AS, Gill BS. Development of a virus-induced gene-silencing system for hexaploid wheat and its use in functional analysis of the Lr21-mediated leaf rust resistance pathway. Plant Physiol. 2005;138:2165–2173. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.061861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vergara CE, Carpita NC. β-D-glycan synthases and the CesA gene family: Lessons to be learned from the mixed-linkage (1 → 3),(1 → 4)-β-D-glucan synthase. Plant Mol Biol. 2001;47:145–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burton RA, et al. Cellulose synthase-like CslF genes mediate the synthesis of cell wall (1 → 3),(1 → 4)-β-D-glucans. Science. 2006;311:1940–1942. doi: 10.1126/science.1122975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kubo M, et al. Transcription switches for protoxylem and metaxylem vessel formation. Gene Dev. 2005;19:1855–1860. doi: 10.1101/gad.1331305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goichoechea M, et al. EgMYB2, a new transcriptional activator from Eucalyptus xylem, regulates secondary cell wall formation and lignin biosynthesis. Plant J. 2005;43:553–567. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02480.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vazquez F. Arabidopsis endogenous small RNAs: Highways and byways. Trends Plants Sci. 2006;11:460–468. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2006.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mallory AC, Dugas DV, Bartel DP, Bartel B. MicroRNA regulation of NAC-domain targets is required for proper formation and separation of adjacent embryonic, vegetative, and floral organs. Curr Biol. 2004;14:1035–1046. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lauter N, Kampani A, Carlson S, Goebel M, Moose S. microRNA172 down-regulates glossy15 to promote vegetative phase change in maize. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:9412–9417. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503927102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Taylor NG, Gardiner JC, Whiteman R, Turner SR. Cellulose synthesis in the Arabidopsis secondary cell wall. Cellulose. 2004;11:329–338. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Taylor NG. Cellulose biosynthesis and deposition in higher plants. New Phytol. 2008;178:239–252. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2008.02385.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brown DM, Zeef LAH, Ellis J, Goodacre R, Turner SR. Identification of novel genes in Arabidopsis involved in secondary cell wall formation using expression profiling and reverse genetics. Plant Cell. 2005;17:2281–2295. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.031542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Milioni D, Sado P, Stacey NJ, Roberts K, McCann MC. Early gene expression associated with the commitment and differentiation of a plant tracheary element is revealed by cDNA-amplified fragment length polymorphism analysis. Plant Cell. 2002;14:2813–2824. doi: 10.1105/tpc.005231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Henz SR, et al. Distinct expression patterns of natural antisense transcripts in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2007;144:1247–1255. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.100396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Borsani O, Zhu J, Verslues P, Sunkar R, Zhu J-K. Endogenous siRNAs derived from a pair of natural cis-antisense transcripts regulate salt tolerance in Arabidopsis. Cell. 2005;123:1279–1291. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.11.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Katiyar-Agarwal S, et al. A pathogen-inducible endogenous siRNA in plant immunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:18002–18007. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608258103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Okamura K, Balla S, Martin R, Liu N, Lai EC. Two distinct mechanisms generate endogenous siRNAs from bidirectional transcription in Drosophila melanogaster. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2008;15:581–590. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ghildiyal M, et al. Endogenous siRNAs derived from transposons and mRNAs in Drosophila somatic cells. Science. 2008;320:1077–1081. doi: 10.1126/science.1157396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Watanabe T, et al. Endogenous siRNAs from naturally formed dsRNAs regulate transcripts in mouse oocytes. Nature. 2008;453:539–544. doi: 10.1038/nature06908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vaistij FE, Jones L, Baulcombe DC. Spreading of RNA targeting and DNA methylation in RNA silencing requires transcription of the target gene and a putative RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. Plant Cell. 2002;14:857–867. doi: 10.1105/tpc.010480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Voinnet O, Vain P, Angell S, Baulcombe DC. Systemic spread of sequence-specific transgene RNA degradation in plants is initiated by localized introduction of ectopic promoterless DNA. Cell. 1998;95:177–187. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81749-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moissiard G, Parizotto EA, Himber C, Voinnet O. Transitivity in Arabidopsis can be primed, requires the redundant action of the antiviral Dicer-like 4 and Dicer-like 2, and is compromised by viral-encoded suppressor proteins. RNA. 2007;13:1268–1278. doi: 10.1261/rna.541307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Delmer DP. Cellulose biosynthesis: Exciting times for a difficult field of study. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1999;50:245–276. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.50.1.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li L, et al. Genome-wide transcription analyses in rice using tiling microarrays. Nat Genet. 2006;38:124–129. doi: 10.1038/ng1704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lu C, et al. Genome-wide analysis for discovery of rice microRNAs reveals natural antisense microRNAs (nat-miRNAs) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:4951–4956. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708743105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chao H, Spicer AP. Natural antisense mRNAs to hyaluronan synthase 2 inhibit hyaluronan biosynthesis and cell proliferation. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:27513–27522. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411544200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jin H, Vacic V, Girke T, Lonardi S, Zhu J-K. Small RNAs and the regulation of cis-natural antisense transcripts in Arabidopsis. BMC Mol. Biol. 2008;9:6. doi: 10.1186/1471-2199-9-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen H-M, Li Y-H, Wu S-H. Bioinformatic prediction and experimental validation of a microRNA-directed tandem trans-acting siRNA cascade in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:3318–3323. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611119104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gibeaut D, Pauly M, Bacic A, Fincher GB. Changes in cell wall polysaccharides in developing barley (Hordeum vulgare) coleoptiles. Planta. 2005;221:729–738. doi: 10.1007/s00425-005-1481-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pfaffl MW. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucl Acids Res. 2001;29:2002–2007. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.9.e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chenna R, et al. Multiple sequence alignment with the Clustal series of programs. Nucl Acids Res. 2003;31:3497–3500. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pogue GP, Lindbo JA, Dawson WO, Turpen TH. Tobamovirus transient expression vectors: Tools for plant biology and high-level expression of foreign proteins in plants. In: Gelvin SB, Schilperoot RA, editors. Plant Mol Biol Manual. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer; 1998. pp. 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- 38.McCann MC, et al. Neural network analyses of infrared spectra for classifying cell wall architectures. Plant Physiol. 2007;143:1314–1326. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.093054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Updegraff D. Semimicro determination of cellulose in biological materials. Anal Biochem. 1969;32:420–424. doi: 10.1016/s0003-2697(69)80009-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Anderson MA, Stone BA. A new substrate for investigating the specificity of β-glucan hydrolases. FEBS Lett. 1975;52:202–207. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(75)80806-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Urbanowicz BR, Rayon C, Carpita NC. Topology of the maize mixed linkage (1 → 3),(1 → 4)-β-D-glucan synthase at the Golgi membrane. Plant Physiol. 2004;134:758–768. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.032011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.