Abstract

Study Objectives:

Cerebral sympathetic activity constricts cerebral vessels and limits increases in cerebral blood flow (CBF), particularly in conditions such as hypercapnia which powerfully dilate cerebral vessels. As hypercapnia is common in sleep, especially in sleep disordered breathing, we tested the hypothesis that sympathetic innervation to the cerebral circulation attenuates the CBF increase that accompanies increases in PaCO2 in sleep, particularly in REM sleep when CBF is high.

Design:

Newborn lambs (n = 5) were instrumented to record CBF, arterial pressure (AP) intracranial pressure (ICP), and sleep-wake state (quiet wakefulness (QW), NREM, and REM sleep). Cerebral vascular resistance was calculated as CVR = [AP-ICP]/CBF. Lambs were subjected to 60-sec tests of hypercapnia (FiCO2 = 0.08) during spontaneous sleep-wake states before (intact) and after sympathectomy (bilateral superior cervical ganglionectomy).

Results:

During hypercapnia in intact animals, CBF increased and CVR decreased in all sleep-wake states, with the greatest changes occurring in REM (CBF 39.3% ± 6.1%, CVR −26.9% ± 3.6%, P < 0.05). After sympathectomy, CBF increases (26.5% ± 3.6%) and CVR decreases (−21.8% ± 2.1%) during REM were less (P < 0.05). However the maximal CBF (27.8 ± 4.2 mL/min) and minimum CVR (1.8 ± 0.3 mm Hg/ min/mL) reached during hypercapnia were similar to intact values.

Conclusion:

Hypercapnia increases CBF in sleep and wakefulness, with the increase being greatest in REM. Sympathectomy increases baseline CBF, but decreases the response to hypercapnia. These findings suggest that cerebral sympathetic nerve activity is normally withdrawn during hypercapnia in REM sleep, augmenting the CBF response.

Citation:

Cassaglia PA; Griffiths RI; Walker AM. Sympathetic withdrawal augments cerebral blood flow during acute hypercapnia in sleeping lambs. SLEEP 2008;31(12):1729–1734.

Keywords: Hypercapnia, cerebral blood flow, sympathetic nervous system, cerebral vascular resistance, lamb

CEREBRAL VESSELS ARE EXTREMELY SENSITIVE TO FLUCTUATIONS IN THE ARTERIAL PARTIAL PRESSURE OF CARBON DIOXIDE (PACO2),1 AND EXPERIMENTALLY induced hypercapnia increases cerebral blood flow (CBF) in all species studied, including sheep2 and humans.3,4 However, CBF responses to natural increases in PaCO2, particularly those occurring in sleep, are less clear. Natural increases in PaCO2 are common in sleep, particularly in REM sleep when ventilation is highly variable and CBF is high.5 Moreover, CBF is increased in conditions such as sleep apnea syndrome (SAS) which is associated with recurring increases in CO2 during apneic pauses.6 While average CBF is high in SAS patients, the variability of CBF during apneic episodes is also pronounced,5 possibly due to arterial or cerebral tissue PCO2 reductions occurring at the termination of an apnea.6

Speculatively, neural influences on cerebral vessels may also contribute to CBF variability in apnea.6 Cerebral vessels are richly innervated by sympathetic nerve fibers,7 with the primary source being the superior cervical ganglion (SCG).8 Increases in sympathetic nerve activity (SNA) from the SCG limit increases in CBF by increasing cerebral vascular resistance (CVR) when blood pressure is increased.9 Cerebral SNA appears to have an important role in sleep as bilateral excision of the SCG in lambs decreases CVR and increases baseline CBF across all sleep-wake states, particularly in REM sleep.10 Adding to the evidence for a protective role of cerebral SNA in normal sleep, increases in intracranial pressure (and putatively cerebral blood volume) that occur during the natural arterial pressure surges of REM sleep are twice as great after cerebral sympathectomy.10

To date, studies investigating the role of sympathetic activation during the cerebrovascular response to hypercapnia have been conflicting. Some studies conducted in conscious humans have suggested that increases in SNA attenuate the rise in CBF associated with hypercapnia,11 while others have shown no modulating effect.4,12 Whether augmented SNA might limit CBF during hypercapnia in sleep has not been investigated, but this may be clinically important in conditions such as SAS when sympathetic activity is high.13 The characterization of cerebrovascular responses to hypercapnia in sleep is of interest as CBF varies widely during apneic events in REM, rising during apnea then reaching very low levels at its termination, possibly increasing the risk of ischemic stroke.6

The aim of this study was to investigate the role of the cerebral sympathetic innervation in the cerebral circulation during acute hypercapnia, using a sleeping lamb model. We hypothesized that a protective increase in cerebral sympathetic outflow would attenuate the elevation in CBF associated with increases in PaCO2, and that this effect would be most prominent in REM sleep when CBF is substantially elevated.

METHODS

Animals

Studies were conducted on 5 lambs (Merino/Border-Leicester cross). Each lamb was separated from its ewe within 24 h of birth and subsequently housed within a Plexiglas cage in the company of other lambs. The animals were taught to feed from a nipple that was connected to a continuous supply of lamb milk replacer (Veanavite, Shepparton, Australia) and gained weight normally (200–300 g/day). All surgical and experimental procedures were performed in accordance with the guidelines of the Australian Code of Practice for the Care and Use of Animals for Scientific Purposes established by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia, and were approved by the Monash University-Monash Medical Center Committee on Ethics in Animal Experimentation. At the completion of surgical procedures animals were treated with IM injections of antibiotic (Ilium Oxytet-200, 0.5 mL, Troy Laboratories, Smithfield, Australia) and analgesic (Finadyne, 1mg/kg, Schering-Plough, Australia), then allowed a minimum of 48 h to recover from surgery before sleep recordings began.

Surgery

Lambs were instrumented for sleep studies using sterile surgical techniques while under general anesthesia (halothane 1.5%, oxygen 50%, balance N2O). The animal's scalp was incised along the sagittal suture and retracted to expose the skull. To record CBF, a 2-cm by 2-cm section of skull was removed just anterior to the lambdoid suture to expose the dura overlying the superior sagittal sinus. Small incisions were made in the dura on either side of the sinus and a transit-time ultrasonic flow probe (2-mm diameter, Transonic Systems, Ithaca, NY) was implanted around the sinus. The probe was stabilized with a rigid cap of dental acrylic to replace the section of removed skull. The technique has been validated for accurate, beat-beat measurement of CBF.14

To determine sleep-wake states, pairs of Teflon-coated stainless-steel electrodes were placed on the parietal cortex (electrocorticogram, ECoG), subcutaneously at the inner and outer canthus of the left eye (electrooculogram, EOG), and in the dorsal musculature of the neck (electromyogram, EMG). A saline-filled catheter (1.57-mm ID, 2.41-OD) was placed under the dura to record intracranial pressure (ICP). A heparin-saline filled catheter (0.86-mm ID, 1.52-mm OD) was implanted nonocclusively in a femoral artery for arterial blood pressure (AP) monitoring and blood sampling.

Sleep Studies

Data were recorded during spontaneous sleep. The lamb's cage was partitioned to prevent the lamb from turning while allowing it freedom to move backward and forward, and to lie down or stand at will. Lambs were allowed free access to food throughout the study. Room lighting (12-h light-dark cycles) and temperature (23–25°C) were controlled.

The CBF probe was connected to a flow meter (Model T101, Ultrasonic Blood Flow Meter, Transonic Systems, Ithaca, NY). Carotid and intracranial catheters were connected to calibrated strain gauge manometers (Cobe CDX III, Cobe Laboratories, Lakewood, CO, USA) referenced to the lamb's mid-thoracic level when in the lying position. Pressure and flow signals were low-pass filtered at 100 Hz. Electrophysiological signals were amplified and filtered (ECoG, 0.3–40 Hz; EOG, 0.3–40 Hz; EMG, 30–100 Hz).

Hypercapnia

Hypercapnia was administered by passing an 8% CO2 gas (19% O2, balance N2) mixture at 25 L/min through a clear plastic chamber enclosing the lamb's head. Three hypercapnic tests of 60-sec duration were induced in each sleep-wake state (QW, NREM, and REM). To ensure the hypercapnia exposure was consistent over the study, arterial blood samples for analysis of blood gases and pH were collected at 60 sec of hypercapnia in 2 exposures, one at the beginning and one at the end of the experiment.

Sympathectomy

After the initial sleep study in the intact animal, each lamb underwent surgical sympathectomy as described previously10 before sleep studies were repeated. Briefly, the sympathetic trunk was accessed via a midline neck incision made caudal to the level of the jaw. The vagus nerve was located and followed to the point where the cervical sympathetic trunk visibly separated to continue on to the SCG. A section of the sympathetic trunk (≥ 1 cm) immediately caudal to the SCG was surgically removed bilaterally (SCGx). The lambs were again given ≥ 48 h to recover from sympathectomy before sleep studies were repeated.

Data Analysis

All signals were digitized and recorded at a sampling frequency of 400 Hz, using a data acquisition-recording system (Powerlab, v5.3, ADI Instruments, TX). Chart v5.3 (ADI Instruments, TX, USA) was used for storage and off-line analysis of all digitized signals.

Cardiovascular data from well-defined epochs of QW, NREM, and REM were averaged sec-by-sec using Chart v5.3 (ADI Instruments, TX). CBF, ICP, and mean AP (MAP) values were used to calculate CVR as follows; CVR = [MAP—ICP] / CBF.

To examine MAP, CBF, and CVR during hypercapnia exposures, data were analyzed over 2-min epochs, beginning 30 sec before and ending 30 sec after the 60-sec exposure to hypercapnia. Values were normalized for each test as a percentage of baseline calculated over a 30-sec period immediately preceding the exposure to hypercapnia. An average of the 3 hypercapnic tests in each state was obtained for each animal, in each sleep-wake state. Coherent sec-sec group averages were then calculated to describe MAP, CBF, and CVR changes over the total 120-sec epoch. An average of the final 10 sec of the 60- sec exposure to hypercapnia (peak response) was used for comparison between each of the sleep states, and between intact and sympathectomized (SCGx) groups.

Statistics

Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Values were compared using 2-way repeated measures ANOVA with a Student-Newman-Keuls post hoc analysis. A probability (P) of < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Baseline Parameters

Lamb weight was 8.8 ± 0.8 kg and age 21 ± 2d (n=5). Sleepstate specific values for MAP, CBF and CVR for intact and SCGx groups are shown in Table 1. Baseline CBF was highest during REM sleep in both control and SCGx groups compared to QW and NREM sleep (P < 0.05). In both groups CVR was lowest during REM sleep compared to QW and NREM sleep (P < 0.05). No change in MAP was observed between sleep-wake states. The present data support previous studies showing higher baseline CBF and lower baseline CVR during REM sleep.15

Table 1.

Cerebral Hemodynamics During Sleep in Lambs Before (Intact) and After Sympathectomy (SCGx)

| Arterial Blood Pressure mm Hg |

Cerebral Blood Flow mL/min |

Cerebral vascular Resistance mm Hg/mL/min |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sleep State | Intact | SCGx | Intact | SCGx | Intact | SCGx |

| QW | ||||||

| Control | 77.3 ± 2.0 | 74.6 ± 2.2 | 14.2 ± 2.1 | 15.6 ± 2.1† | 3.9 ± 0.4 | 3.2 ± 0.4† |

| Hypercapnia | 78.4 ± 3.8 | 73.3 ± 2.4 | 17.1 ± 2.3 | 18.9 ± 3.3 | 3.2 ± 0.3 | 2.6 ± 0.3 |

| Change % | 1% | 1% | 19% | 21% | −16% | −19% |

| NREM | ||||||

| Control | 73.6 ± 2.6 | 75.2 ± 2.7 | 13.9 ± 2.3 | 15.8 ± 1.8† | 4.0 ± 0.5 | 3.3 ± 0.4† |

| Hypercapnia | 77.5 ± 3.8 | 75.5 ± 3.7 | 17.4 ± 2.2 | 19.5 ± 2.7 | 3.1 ± 0.4 | 2.7 ± 0.3 |

| Change | 5% | 1% | 19% | 17% | −18% | −20% |

| REM | ||||||

| Control | 73.2 ± 2.1 | 74.3 ± 4.5 | 19.1 ± 3.0*# | 23.3 ± 3.1*#† | 2.9 ± 0.3*# | 2.2 ± 0.2*#† |

| Hypercapnia | 74.5 ± 2.1 | 73.4 ± 5.2 | 28.9 ± 3.6 | 27.8 ± 4.2 | 2.1 ± 0.4 | 1.8 ± 0.3 |

| Change | 1% | 1% | 39% | 27% | −27% | −22% |

P < 0.05 compared to QW.

P < 0.05 compared to NREM sleep.

P < 0.05 compared between control and SCGx in same sleep-wake state.

Intact versus SCGx

Consistent with previous data10 CBF was higher in the SCGx group in all sleep-wake states compared to the intact group (P < 0.05). Correspondingly, CVR was lower in the SCGx group (P < 0.05). There was no difference in MAP between the intact and SCGx group.

Hypercapnia

Table 2 shows arterial blood gases during control conditions and at 60 sec of hypercapnia in both the intact and SCGx group. There were no differences between the intact and SCGx group. In hypercapnia, PaCO2 increased from baseline by 10.4 ± 1.2 mm Hg and 9.5 ± 1.1 mm Hg in the intact and SCGx group, respectively; pH decreased by 0.1 and 0.8; PaO2 increased by 16.0 ± 4.1 mm Hg and 15.1 ± 7.1 mm Hg; there were no changes in SaO2.

Table 2.

Arterial Blood Gases in Air Breathing (Control) and Hypercapnia (8% Inspired CO2) in Lambs (n = 5) Before (Intact) and After Sympathectomy (SCGx)

| PaCO2 (mm Hg) |

PaO2 (mm Hg) |

SaO2 (%) |

pH |

Hb (g/dL) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intact | SCGx | Intact | SCGx | Intact | SCGx | Intact | SCGx | Intact | SCGx | |

| Control | 40.0 ± 0.9 | 40.8 ± 1.7 | 97.1 ± 2.2 | 97.9 ± 2.5 | 97 ± 1.7 | 97 ± 1.5 | 7.46 ± 0.01 | 7.43 ± 0.01 | 8.1 ± 0.6 | 8.1 ± 0.5 |

| Hypercapnia | 50.5 ± 0.9* | 49.5 ± 1.4* | 113.2 ± 4.4* | 114.5 ± 4.3* | 98 ± 1.5 | 98 ± 2.0 | 7.36 ± 0.02* | 7.37 ± 0.01* | 8.1 ± 0.8 | 8.2 ± 0.6 |

Blood gases in hypercapnic group taken after 60 sec of 8% CO2 exposure.

P < 0.05 between control and hypercapnia in the intact group: P < 0.05. #P < 0.05 between control and hypercapnia in the sympathectomized group.

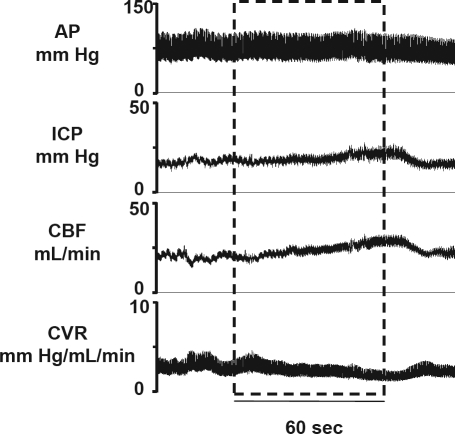

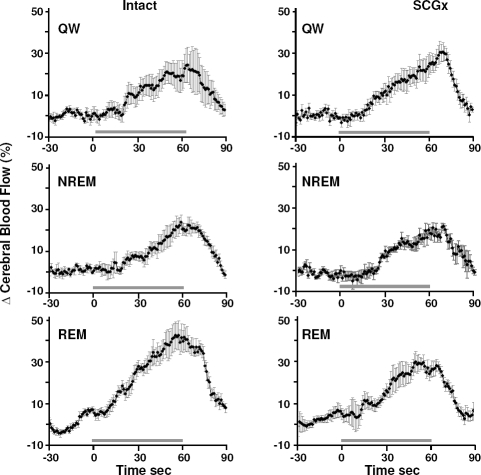

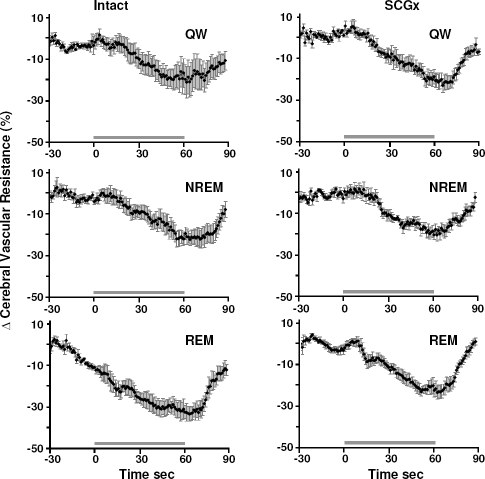

An illustrative example of circulatory responses to a hypercapnia test is shown in Figure 1. Consistently in all states, hypercapnia resulted in a gradual increase in CBF and ICP, and a corresponding decrease in CVR. No change was observed in AP in response to hypercapnia. Figures 2 and 3 show coherent sec-sec changes in CBF and CVR respectively during hypercapnia averaged for intact and SCGx lambs (n = 5) in QW, and NREM and REM sleep.

Figure 1.

Representative physiological recording during a 60- sec hypercapnia (8% CO2) exposure in NREM sleep. Dashed box represents the period of hypercapnia. Note the increase in CBF, ICP and decrease in CVR in response to hypercapnia, with no change in AP.

Figure 2.

Coherent sec by sec averages of changes in CBF in response to hypercapnia in % from baseline in the intact and sympathectomized (SCGx) group of lambs (n = 5). CBF increased in response to hypercapnia exposure (horizontal line) in all sleep-wake states in both groups. In the intact group, but not the SCGx group, the increase in CBF was higher in REM sleep compared to QW and NREM sleep (P < 0.05). The increase in CBF was higher in the intact group compared to the SCGx group in REM sleep (P < 0.05). Error bars represent SEM.

Figure 3.

Coherent sec by sec averages of changes in CVR in response to hypercapnia in % from baseline in the intact and sympathectomized (SCGx) group of lambs (n = 5). CVR decreased in response to hypercapnia exposure (horizontal line) in all sleep-wake states in both groups. In the intact group, but not the SCGx group, the decrease in CVR was greater in REM sleep compared to QW and NREM sleep (P < 0.05). The decrease in CVR was greater in the intact group compared to the SCGx group in REM sleep (P < 0.05). Error bars represent SEM.

Peak circulatory responses from baseline to hypercapnia in the intact group were; for CBF, QW 18.7% ± 5.6%, NREM 18.6% ± 4.2%, REM 39.3% ± 6.1% (all P < 0.05); and for CVR, QW –15.5% ± 5.2%, NREM –17.8% ± 4.1%, REM –26.9% ± 3.6% (all P < 0.05). For both CBF and CVR, the response to hypercapnia was greatest in REM sleep compared to QW (P < 0.05) and NREM sleep (P < 0.05).

In the SCGx group peak responses were as follows; for CBF, QW 20.7% ± 4.8%, NREM 17.0% ± 2.5%, REM 26.5% ± 3.6% (all P < 0.05); and for CVR, QW –19.1% ± 3.1%, NREM –20.1% ± 2.0%, REM –21.8% ± 2.1% (all P < 0.05). No sleepwake differences existed in the CBF and CVR changes of SCGx animals.

Intact versus SCGx

During REM sleep the increase in CBF in response to hypercapnia was greater in the intact group compared to the SCGx group (39.3% ± 6.1% and 26.5% ± 3.6%, respectively, P < 0.05) while the maximum CBF values of the intact and SCGx group were not significantly different (28.9 ± 3.6 mL/min and 27.8 ± 4.2 mL/min, respectively). Similarly, in REM sleep the peak decrease in CVR in response to hypercapnia was significantly larger in the intact group compared to the SCGx group (−26.9% ± 3.6% and −21.8% ± 2.1% respectively, P < 0.05) while the absolute minimum values between the intact and SCGx group were not significantly different (2.1 ± 0.4 mm Hg/min/mL and 1.8 ± 0.3 mm Hg/min/mL respectively). No difference in CBF and CVR responses between intact and SCGx groups was observed for QW or NREM sleep.

DISCUSSION

The main findings of our study are that: (1) the cerebrovascular response to hypercapnia varies between sleep-wake states, with the relative increase in CBF being greatest during REM sleep; (2) after sympathectomy, baseline CBF was greater than in intact animals, while the peak level of CBF reached was similar, so that the hypercapnia-induced increment of CBF in REM was less. Similarly, baseline CVR was less after sympathectomy, while the minimum reached in hypercapnia was similar to the intact animal, making the hypercapnia-induced CVR reduction less. These results indicate that cerebral sympathetic activity is normally tonically active in REM sleep, and is withdrawn during periods of imposed hypercapnia, augmenting the hypercapnia-induced cerebral vasodilatation and contributing to hyperemia.

The exposure to hypercapnia induced an increase in PaCO2 of approximately 10 mm Hg (Table 2), comparable to previous studies of induced hypercapnia in humans and rats.16–18 The increase of approximately 15 mm Hg in PaO2 observed during hypercapnia is likely to be due to the increase in respiratory frequency,18,19 and at normal levels of arterial oxygenation has essentially no influence on CVR or CBF.20

Previous investigations have identified several candidate mechanisms for increasing CBF during hypercapnia, the principal one being a direct vasodilator effect of CO2 on cerebral vessels mediated by an increase in extracellular pH.21 Additional to the direct CO2-mediated vasodilatation other complex and interrelated mechanisms have been implicated and shown to play permissive roles, principally the release of endothelial nitric oxide and prostaglandins.22–25 Whatever the fundamental vasodilating mechanism, our results provide evidence that it is augmented by a withdrawal of tonic sympathetic vasoconstrictor activity to cerebral vessels. Interestingly, this withdrawal is in contrast to the augmentation of vasoconstrictor activity occurring in the systemic circulation during hypercapnia. Activation of central chemoreceptors in the medulla leads to a reflex sympathetic vasoconstriction in non-cerebral vessels to counteract the direct vasodilatation.17,26 In the present study, no evidence of a reflex increase in systemic AP was observed during the 60-sec exposure (Figure 1), indicating that an increase in systemic sympathetic outflow adequately compensated for hypercapnia-induced vasodilatation.

Whether sympathetic nerve activity to cerebral vessels normally modulates the cerebrovascular response to CO2 has been uncertain. Some studies have used baroreceptor unloading as a means to increase sympathetic nerve activity during hypercapnia,4,11 a maneuver that is unlikely to affect cerebral sympathetic activity as this is not augmented when arterial pressure falls.9 Data derived using ganglion blockade to reduce sympathetic tone are also inconsistent11,12 perhaps because the accompanying systemic hypotension required correction with phenylephrine that itself may have altered cerebrovascular responses. In our study, ganglionectomy had no affect upon systemic arterial pressure, and no correction was needed. An interesting finding was that compared to QW and NREM sleep, the cerebrovascular response to hypercapnia was greatest during REM sleep (Figures 2 and 3). This finding was only evident in the intact group of lambs, demonstrating that sympathetic activation normally plays a significant role in regulating cerebrovascular responses in REM sleep. Here we have found evidence that withdrawal of cerebral sympathetic activity occurs during acute hypercapnia in REM, as both the increase of CBF and the decrease of CVR were less after sympathectomy. By contrast, responses of intact and SCGx groups were similar for QW and NREM. The greater effect in REM is in keeping with human studies showing that REM sleep is a sympathetically dominated behavioral state.27 Moreover, SNA appears less important in CBF regulation during QW and NREM sleep than in REM sleep in lambs.10

Our findings may have implications for understanding cerebral hemodynamics in patients suffering from sleep apnea. These patients have elevated sympathetic tone in wakefulness and sleep, with the increase being most exaggerated during REM sleep.13 Notably, while average CBF is high in these patients, at the termination of an apnea CBF falls rapidly, often to levels below normal.48 The rapidity of the CBF fall and its relationship to EEG changes suggests a direct neuronal mechanism related to arousal, possibly sympathetic activation. It has been also speculated that arterial or cerebral tissue PCO2 reductions after the resumption of breathing may also contribute.6 On the basis of our present data, both reinstated vasoconstrictor SNA and a fall in PCO2 may contribute to the fall in CBF at apnea termination.

In conclusion, we have identified that withdrawal of cerebral SNA contributes to the cerebral vasodilatation induced by hypercapnia, with the largest effect occurring in REM sleep. Withdrawal of SNA during apnea and its reinstitution at the termination of apnea may explain the marked variation of CBF that is a feature of disordered breathing in REM sleep.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia.

We express our gratitude to Dr. S. Feng and Ms. Lyndsay McClure for expert technical assistance.

ABBREVIATIONS

- AP

arterial pressure

- CBF

cerebral blood flow

- CVR

cerebral vascular resistance

- ICP

intracranial pressure

- MAP

mean arterial pressure

- PaCO2

arterial partial pressure of carbon dioxide

- PCO2

partial pressure of carbon dioxide.

- SAS

sleep apnea syndrome

- SCG

superior cervical ganglion

- SCGx

superior cervical sympathectomy

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement

This was not an industry supported study. The authors have indicated no financial conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Brian JE., Jr. Carbon dioxide and the cerebral circulation. Anesthesiology. 1998;88:1365–86. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199805000-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rosenberg AA, Jones MD, Jr, Traystman RJ, Simmons MA, Molteni RA. Response of cerebral blood flow to changes in PCO2 in fetal, newborn, and adult sheep. Am J Physiol. 1982;242:H862–6. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1982.242.5.H862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ainslie PN, Ashmead JC, Ide K, Morgan BJ, Poulin MJ. Differential responses to CO2 and sympathetic stimulation in the cerebral and femoral circulations in humans. J Physiol. 2005;566:613–24. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.087320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.LeMarbre G, Stauber S, Khayat RN, Puleo DS, Skatrud JB, Morgan BJ. Baroreflex-induced sympathetic activation does not alter cerebrovascular CO2 responsiveness in humans. J Physiol. 2003;551:609–16. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.046987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hajak G, Klinkefus J, Schulz-Varszegi M, et al. Cerebral perfusion during sleep-disordered breathing. J Sleep Res. 1995;4:135–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.1995.tb00203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hajak G, Klingelhofer J, Schulz-Varszegi M, Sander D, Ruther E. Sleep apnea syndrome and cerebral hemodynamics. Chest. 1996;110:670–9. doi: 10.1378/chest.110.3.670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Edvinsson L, Hamel E. Perivascular nerves in brain vessels. In: Edvinsson L, Krause D, editors. Cerebral blood flow and metabolism. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Edvinsson L, Owman C, Rosengren E, West KA. Concentration of noradrenaline in pial vessels, choroid plexus, and iris during two weeks after sympathetic ganglionectomy or decentralization. Acta Physiol Scand. 1972;85:201–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1972.tb05251.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cassaglia PA, Griffiths RI, Walker AM. Sympathetic nerve activity in the superior cervical ganglia increases in response to imposed increases in arterial pressure. Am J Physiol. 2008;294:R1255–61. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00332.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Loos N, Grant D, Wild J, et al. Sympathetic nervous control of the cerebral circulation in sleep. J Sleep Res. 2005;14:275–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2005.00464.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jordan J, Shannon J, Diedrich A, et al. Interaction of carbon dioxide and sympathetic nervous system activity in the regulation of cerebral perfusion in humans. Hypertension. 2000;36:383–8. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.36.3.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Przybylowski T, Bangash M-F, Reichmuth K, Morgan BJ, Skatrud JB, Dempsey JA. Mechanisms of the cerebrovascular response to apnoea in humans. J Physiol. 2003;548:323–32. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.029678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Somers V, Dyken M, Clary M, Abboud F. Sympathetic neural mechanisms in obstructive sleep apnea. J Clin Invest. 1995;96:1897–904. doi: 10.1172/JCI118235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grant D, Franzini C, Wild J, Walker A. Continuous measurement of blood flow in the superior sagittal sinus of the lamb. Am J Physiol. 1995;269:R274–9. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1995.269.2.R274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Franzini C. Brain metabolism and blood flow during sleep. J Sleep Res. 1992;1:3–6. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Somers V, Mark A, Abboud F. Interaction of baroreceptor and chemoreceptor reflex control of sympathetic nerve activity in normal humans. J Clin Invest. 1991;87:1953–7. doi: 10.1172/JCI115221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oikawa S, Hirakawa H, Kusakabe T, Nakashima Y, Hayashida Y. Autonomic cardiovascular responses to hypercapnia in conscious rats: the roles of the chemo- and baroreceptors. Auton Neurosci. 2005;117:105–14. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2004.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ito H, Kanno I, Ibaraki M, Hatazawa J, Miura S. Changes in human cerebral blood flow and cerebral blood volume during hypercapnia and hypocapnia measured by positron emission tomography. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2003;23:665–70. doi: 10.1097/01.WCB.0000067721.64998.F5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tamisier R, Nieto L, Anand A, Cunnington D, Weiss JW. Sustained muscle sympathetic activity after hypercapnic but not hypocapnic hypoxia in normal humans. Resp Physiol Neurobiol. 2004;141:145–55. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2004.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Greenberg J. Sleep and the cerebral circulation. In: Orem J, Barnes C, editors. Physiology in sleep. New York: Academic Press Inc; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kontos HA, Wei EP, Raper AJ, Patterson JL., Jr Local mechanism of CO2 action of cat pial arterioles. Stroke. 1977;8:226–9. doi: 10.1161/01.str.8.2.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Busija DW, Heistad DD. Effects of indomethacin on cerebral blood flow during hypercapnia in cats. Am J Physiol. 1983;244:H519–24. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1983.244.4.H519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Iadecola C, Zhang F. Permissive and obligatory roles of NO in cerebrovascular responses to hypercapnia and acetylcholine. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:R990–1001. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1996.271.4.R990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McPherson RW, Kirsch JR, Ghaly RF, Traystman RJ. Effect of nitric oxide synthase inhibition on the cerebral vascular response to hypercapnia in primates. Stroke. 1995;26:682–7. doi: 10.1161/01.str.26.4.682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heinert G, Nye PC, Paterson DJ. Nitric oxide and prostaglandin pathways interact in the regulation of hypercapnic cerebral vasodilatation. Acta Physiol Scand. 1999;166:183–93. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-201x.1999.00558.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fukuda Y, Sato A, Suzuki A, Trzebski A. Autonomic nerve and cardiovascular responses to changing blood oxygen and carbon dioxide levels in the rat. J Auton Nerv Syst. 1989;28:61–74. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(89)90008-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Somers VK, Dyken ME, Mark AL, Abboud FM. Sympathetic-nerve activity during sleep in normal subjects. New Engl J Med. 1993;328:303–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199302043280502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]