Abstract

In Ontario, the 18-month well-baby visit is the last scheduled primary care visit before school entry. Recognizing the importance of this visit and the role that primary care plays in developmental surveillance, an Ontario expert panel recommended enhancing the 18-month visit. Their recommendations are based on evidence from multiple disciplines, which underscore the reality that the quality of the early years experience establishes trajectories of health and well-being for children. An underlying premise of the recommendations is that when there are collaborations among parents, primary care, community health and child development services, the outcomes for children will be improved. The present article focuses on two Ontario pilot projects that were funded to discover how, in real life primary care settings, the recommendations could be implemented and outcomes measured. Findings and insights were significant, and future directions are clear, as the strategy for an enhanced 18-month well-baby visit is implemented in the future for Ontario.

Keywords: 18-month enhanced well-baby visit, Early child development, Primary care

Abstract

En Ontario, la visite de 18 mois de l’enfant bien portant est la dernière visite de première ligne prévue avant la rentrée scolaire. Conscient de l’importance de cette visite et du rôle des soins de première ligne sur la surveillance du développement, un groupe d’experts de l’Ontario a recommandé de l’améliorer. Leurs recommandations se fondent sur des données multidisciplinaires probantes selon lesquelles la qualité de l’expérience des premières années établit des trajectoires de santé et de bien-être pour les enfants. Selon une prémisse sous-jacente des recommandations, grâce à une collaboration entre les parents ainsi que les services de soins de première ligne, de santé communautaire et de développement des enfants, le devenir des enfants s’améliore. Le présent article porte sur deux projets pilotes ontariens mis sur pied pour découvrir comment, en soins de première ligne réels, il serait possible d’implanter les recommandations et de mesurer les issues. Ces projets ont suscité des observations et des constatations importantes et de futures orientations tellement claires que la stratégie en vue d’offrir une visite de 18 mois améliorée pour le bébé bien portant sera mise en oeuvre en Ontario.

The true measure of a nation’s standing is how well it attends to its children – their health and safety, their material security, their education and socialization, and their sense of being loved, valued and included in the families and societies into which they are born (1).

UNICEF’s 2007 Innocenti Report Card (1) on child well being in rich countries is a comprehensive assessment of the lives and well being of children and adolescents in the 21 most economically advanced nations. Canada is ranked 12th out of 21 countries – a statistic that should propel us into action. With the provision of universal health care for Canadian children, there exists a substantive platform from which we should be able to launch children from healthy pregnancies through nurturing early childhoods and continuing on to lifelong trajectories of health, wellbeing and life success. In spite of universal availability, there is differential uptake of health care services for children across this country. As the late Dr Dan Offord frequently said, “in Canada growing up is like a race, and the playing field is not even” (2).

The echoes across a wide variety of scientific evidence from many fields substantiate the formative importance of the early years. From neuroscience (3,4), much has been learned – the hard-wiring of the brain is influenced by early childhood experiences, there are sensitive periods during brain development when sensory inputs are required to develop neurological pathways (5), adverse childhood experiences affect brain architecture (6,7), and activation and expression of genes are impacted by environmental and social influences (8). Economists have also added their voices to the choir led by the Nobel Laureate James Heckman (9) and David Dodge, former governor of the Bank of Canada (10). They have concluded, through extensive and creative analysis, that investing in young children generates the biggest economic return. This has led others (11) to conclude that investment in early child development is a key economic development strategy.

Evaluation and publication of successful programs such as the Perry Preschool project (12), the Abecedarian Project (13), Chicago Child-Parent Centers (14), and impressive nursing home-visiting programs (15) all lead the way in proving that investments in quality programming for children and young families can alter outcomes for success in school, and longer-term for life success. Furthermore, these studies are providing exciting evidence that demonstrate the potential impact of quality environments on gene expression (8,16).

With the groundbreaking work of Lalonde (17) in 1981 and knowledge of the social determinants of health, the attention to the population-based factors, which impact life outcomes, has become a challenge for individual practicing physicians to operationalize in their day-to-day practices. Counselling to ‘not be poor, and certainly not for long’ or to ‘live in richer neighbourhoods’ and ‘have a job with higher levels of control over your work’ is naive and pointless. But figuring out how to adjust one’s practice approaches to accommodate this new knowledge and paradigm is important. The territory of the enhanced 18-month well-baby visit provides that opportunity.

ONTARIO’S PROGRAM

In 2005, Ontario’s newly established Ministry of Children and Youth Services launched its Best Start strategy with the goal of making sure that children in Ontario are ready to learn by the time they begin grade 1 (18).

Before Best Start, there were a number of well-established programs – a universal Healthy Babies, Healthy Children (HBHC) program with a targeted professional nursing and lay home-visiting component for high-risk families, a universal system across the province of parenting resource centres called Ontario early years centres (OEYCs) and family resource centres, and services for nonparental care (eg, childcare). OEYCs are branded community centres that form a network of parent and caregiver supports across Ontario. A wide range of programs and activities for parents and caregivers with their children are available at parent-friendly hours of the day and week. Early years professionals and other parents are available to give advice, guidance and support.

The Best Start initiative called for ‘Best Start Network Tables’ to be established in each region, and because many communities already had planning tables for children’s services, they expanded their mandates. Other communities developed new tables.

As part of the strategy, three expert panels were established to address key issues in the implementation of the vision – an 18-month enhanced well-baby visit panel (19), a quality and human resources panel (20) and an early learning framework panel (21). The present article focuses on the challenges and opportunities of operationalizing the 18-month enhanced well-baby visit panel’s recommendations in Ontario.

Historically, much effort had been invested in targeted marketing to both parents and primary care practitioners (PCPs), including family physicians, paediatricians and nurse practitioners, about the importance of the early years and about the available community resources and programs which were broadly available. Unfortunately, the success of these strategies has been variable and surveys of PCPs identified that they were frequently unaware of these universal resources, and even if they had heard of them, they were unsure of their quality and their significance. Multiple strategies of mailings, e-mail alerts, rounds, presentations, articles and even peer-to-peer training models have been attempted to improve the knowledge and practice attention to the early years, with limited success.

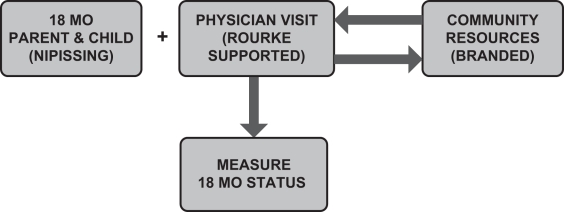

The 18-month expert panel was charged with the task of attempting a new approach and focusing solely on a single-visit opportunity, as a starting point, to enhance the understanding of the early years through a systematic, evidence-based approach, which would be manageable and appropriate in the current Ontario climate. The report from the expert panel titled “Getting it Right at 18 Months…Making it Right for a Lifetime” (19) recommended shifting the focus of the universal 18-month visit from a well-baby check-up (weigh, measure and immunize) to a pivotal assessment of developmental health using PCP and PCP-parent dialogue with prompts. The visit was to include encouragement and support of literacy and positive parenting, the identification of developmental delay and to provide an opportunity to connect families with parenting and other early child development community resources. The expert panel recommended trading physician credibility and physicians’ increased understanding of local community resources for improved connections between families and community resources. The full report (19) and its conclusions are available, but is represented pictorially in Figure 1.

Figure 1).

A pictorial representation of the recommendations of the expert panel for a system change around the enhanced 18-month (mo) well-baby visit. Nipissing Nipissing District Developmental Screen; Rourke Rourke Baby Record

Getting consensus and publishing a report with a recommended model was the easy part – the real challenge was changing physician practice patterns in an environment of well-meaning but overworked, under-resourced primary care sector. A variety of approaches have been taken including the Ontario College of Family Practice developing a practice guideline document (22), the striking of a provincial implementation team to operationalize the recommendations from the expert panel and the funding of two 18-month well-baby visit pilot projects (Niagara, Ontario, and Hamilton, Ontario) to test implementation strategies.

THE NIAGARA PROJECT

Niagara is a diverse region made up of 12 unique and distinct local municipalities, varying from the larger populated cities of St Catharines and Niagara Falls, to the more rural Wainfleet and West Lincoln areas. It is located in southern Ontario and covers 1896 km2, containing a population of approximately 475,000 with 4000 births per year.

Public health programs in Niagara deliver comprehensive social marketing campaigns, strategies and supports, which are directed at parents in the community to improve understanding of their child’s development and to outline what to expect at the 18-month well-baby visit.

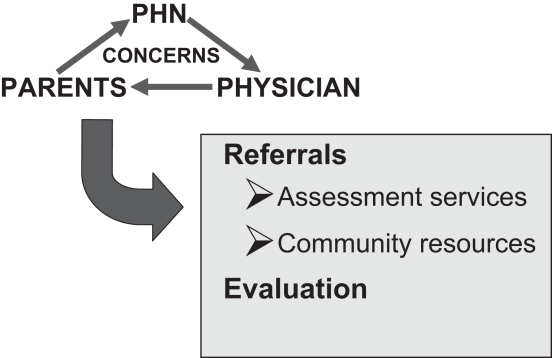

Within this context, the Niagara project sought to augment the universal opportunity of the 18-month visit by providing an ‘attachment’ public health nurse (PHN), with expertise in child health, who would be a direct link to information and resources for the family health team (FHT), as per the project design (Figure 2). The provincially driven mandate of public health and the HBHC programs align well with supporting PCPs, to augment their understanding of current issues in children’s developmental health and influence children’s life trajectories. The PHN assists the PCPs in understanding the complex referral systems for services, the range of and access to community resources, and in collaboration with the PCPs, provides messages and materials about literacy and positive parenting that practitioners can deliver to patients.

Figure 2).

Project design. PHN Public health nurse

THE MECHANICS: THE PHN/TEAM ROLE

Initially, the HBHC PHN and members of the broader team (the medical officer of health, the HBHC and the public health staff, and the preschool speech coordinator) met with the FHT to explain the recommendations of the 18-month report and gain an understanding of the office structure and functioning. The reputation of, and respect for, the local medical officer of health by the primary care community in Niagara was believed to be a critical success factor in getting the conversation started. Communities should build on physician champions when engaging the primary care sector. Collaborative planning and ‘detailing’ of the strengths, opportunities, barriers and challenges around operationalizing the 18-month enhanced visit in this FHT were essential early steps, as well as ensuring that the practice truly shared the vision. The use of the attachment PHN was intended to support the PCP in this project to provide high-quality resources and enhance understanding of children’s developmental health particularly at 18 months, facilitate early identification and support through the use of evidenced-based screening and point-of-care tools (Nipissing District Developmental Screen [NDDS] [Nipissing District Developmental Screen Intellectual Property Association, Canada] or ‘Nipissing’ [23] and the Ontario version of the Rourke Baby Record [RBR-O] [24]), coach content of the 18-month visit, guide PCP and office support staff through the complex referral systems and support them to make more appropriate and timely referrals, when needed.

On the literacy front, PCPs have been supported to assess child developmental health and share literacy key messages through the provision and clinical use of an appropriate 18-month children’s book, which is given to the family. This model is loosely based on the “Reach Out and Read” program (25) and also uses the “Read, Speak and Sing to Your Baby” resource (26), which was developed by the Canadian Paediatric Society.

An implementation guide (Appendix 1) was developed with the Niagara FHT outlining office logistics and practical roles and responsibilities of the FHT members and the attachment PHN. Each primary care setting would have their own unique organizational and patient flow footprint. The time spent with the PCP in working this out is critical.

The literature is clear that parents view recommendations from physicians as being credible and valuable (27,28). A major component of the Niagara project has been the low-key practical coaching and modelling that the PHN has provided during the 18-month interview around parenting and child developmental health. Initially, the PHN attended all 18-month visits with the PCP, modelling effective interview and communication strategies around unfamiliar terrain, such as parenting and car seat safety. The PHN acted to translate the results of the NDDS into practical suggestions and areas of enquiry for the PCP-parent dialogue. This model needed to be fluid and flexible in a busy FHT. The PHN participation in the 18-month interview allowed the nurse to model engagement of the parent and demonstrate questioning styles around parenting through probes and support, as well as share information about community supports and services, (eg, OEYCs, libraries and parenting support groups, as well as links to credible on-line information) (29). The FHT PCPs identified the need for an information package pertinent to an 18-month-old to use as speaking points during the visit and to give parents a takehome reference.

To date, the FHT in Niagara describes high satisfaction with the PHN attachment model. They reported improved confidence and knowledge around content area, community resources, approaches to inquiring and supporting parenting, and believed that the use of the tools (the NDDS and the RBR-O) helped reduce the probability of missing golden opportunities for teaching, enquiry, referrals or linkages. Although the attachment PHN concentrated on the 18-month visits, there were many examples of ‘cross-over’ of information that was useful to the primary care providers in this practice for both older and younger children.

A parent follow-up survey conducted three months postvisit by telephone is currently underway. Preliminary results reveal high satisfaction with the visit:

84% recalled reviewing the NDDS before the visit with their PCP (52% found it very helpful and 20% found it somewhat helpful);

92% recalled hearing about community resources;

44% had used an OEYC and a further 16% reported going after the visit; and

92% reported receiving a book and reported reading it to their 18-month-old.

Focus groups will be conducted with FHT members, and sustainability and ‘booster’ strategies are in development to ensure continued success. Data are also being compiled to obtain a ‘developmental picture’ of the approximately 100 18-month-olds in the FHT who have participated in the pilot study.

A major focus and challenge for the public health department in Niagara is to develop strategies to ‘grow’ this project and to replicate and translate the learnings to other primary care sites. The utilization of ‘key opinion leaders’ and physician champions to engage additional FHTs is being considered. Key learnings from this project include the need to be collaborative and flexible to the individual needs of the FHT, ongoing communication and commitment by all FHT staff to an extended time of approximately 20 min for the visit, and hands-on one-to-one coaching model by the PHN, especially early in the pilot study. The Niagara project experience has revealed a high level of interest from PCPs in children’s developmental health and aligns with the interests and mandate of public health.

THE HAMILTO N PROJECT

Hamilton is an urban southern Ontario community of approximately 550,000 people, with an annual birth rate of approximately 5500 children and close to 300 primary care physicians. As a Best Start demonstration site, Hamilton received the Ministry of Child and Youth Services’ funds to develop a strategy to engage PCPs in the implementation of the 18-month enhanced well-baby visit.

From the outset, it was recognized that the delivery of well-baby care in Ontario and Hamilton involves a variety of care models – solo physician practices, collaborative care between physicians and nurse practitioners, family health teams with joint care between family health nurses and physicians, sole nurse practitioner and public health nurse delivery. A transdisciplinary committee was created, as a subcommittee of the Hamilton Best Start network, to include representation from primary care and public health, as well as family resource and child care services to develop and oversee the project.

The initial goals of the strategy were to:

Affirm that primary care plays an essential and crucial role in healthy child development, and to give an update on the new advances in neuroscience;

Recommend the use of free, easily accessible and efficient tools to assess development and engage parents in their child’s development (ie, the NDDS and the RBR-O);

Encourage PCPs to inform all families of the resources in the community, with a tear-off sheet with the local OEYC contact information; and

Provide PCPs with contact information for other relevant referral community services (eg, preschool speech and language services, infant development and autism services).

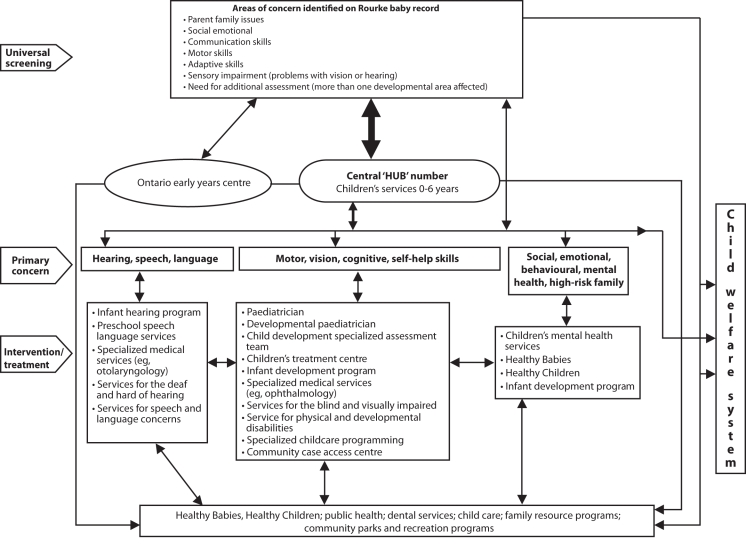

Educational materials were developed by two physicians and promoted for use by local primary care opinion leaders (six physicians and two nurses) to be delivered at rounds, group practices or OEYCs in partnership with public health and local service providers (OEYCs) across Hamilton. A package was distributed at all presentations, which included multiple copies of the NDDS with the Web site source, copies of the RBR-O with the Web site source, an article on the 18-month visit and a desk reference for postpartum depression (30). In addition, a laminated flowchart of local early years services with contact information was developed for distribution. This has proven to be particularly useful and successful with PCPs. Refer to Appendix 2 for the generic version of the 18-month flow chart.

Approximately 300 physicians and nurse practitioners from Hamilton and surrounding areas attended these sessions and 210 completed a presurvey.

The presurvey asked about knowledge and use of the NDDS, the RBR and community resources, as well as satisfaction with their current delivery of the 18-month visit. The results indicated that most practices were aware of the RBR (98%) and used some form of the RBR, with those using electronic medical records wanting access to an electronic version. Many were unaware of the NDDS (48%) and few knew of the community resources apart from the medical services.

A postsurvey was developed and sent to 121 Hamilton PCPs; 70% completed the postsurvey. The data indicate a significant change in awareness and use of the NDDS, particularly as a basis for discussion with parents. A significant increase in referral to OEYCs and overall knowledge of early childhood services was also noted. In addition, the community resources keep a record of the source of their referrals; there was a significant increase in referral to speech and language services by PCPs.

A second educational initiative included a continuing medical education accredited event focusing on a more indepth understanding of attachment, parenting, postpartum depression, autism spectrum and community resources. The evaluations of the 30 participants were positive and indicated a desire for more information and strategies on dealing with parenting and behavioural issues.

FUTURE PLANS FOR ONTAR IO

Although much work has been completed both provincially and locally with these two specific projects, a number of initiatives are currently underway to further develop this into a province-wide strategy. The possibility of interand transprofessional education programs on the social determinants of health and population health principles, using the 18-month well-baby visit as the delta, is creating a buzz of excitement in the academic community. An electronic version of the tools is under development. In addition, given the large newcomer population and low literacy rates of some Ontarians, a pictorial version of the NDDS is being developed, piloted and evaluated in Hamilton. In partnership with McMaster University (Hamilton, Ontario), a proposal for a Web portal for PCPs and parents on healthy child development at the 18-month enhanced well-baby visit is under consideration. The need to monitor the ongoing development of Ontario’s children at a population level was recognized by the expert panel as being a critical requirement, and continues to provide a significant challenge. A variety of initiatives are currently underway across the country in support of realizing this goal. As echoed in the recent report (31) by the federal advisor on healthy children and youth, appropriate data collection and dissemination ultimately results in better decision making, which continues to be important for early child development outcomes and has major implications for later health care needs and planning.

CONCLUSION

Much has been garnered from the implementation of these projects. Parents continue to turn to their PCP for behavioural and parenting advice, and are keenly interested, for the most part, in their child’s healthy growth and development. In spite of significant community resources, PCPs are often unaware of the richness of these resources and their role in enhancing and encouraging healthy growth and development. PCPs are interested in providing benchmarked care, are open to enhancing the 18-month well-baby visit and appreciate physician prompt/point of care records (RBR-O). They face the challenges of changing practice systems and are often dependent on a wide variety of team members for the practical sustainable changes that allow the new approach. Finally, significant time and energy will be required, including changes in the physician and other PCP training environments, changes in funding and the development of the electronic resources required to translate this 18-month well-baby enhanced visit strategy into a system for Ontario’s children and families.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Niagara Falls family health team members and all the physicians and other primary care practitioners in Hamilton who enthusiastically continue to participate in the enhanced 18-month wellbaby pilot projects in these two communities. Dr Linda Comely has been a tireless champion, who with the support of the Ontario College of Family Physicians, worked on many aspects of the strategy in both communities. The authors also thank Dr Pat Mousmanis and Jan Kasperski of the College of Family Physicians, for their review and comments. Thanks is also extended to Jane Bonaldo for her support and guidance in preparation of the manuscript.

APPENDIX 1

Step-by-Step Implementation Guide for the Niagara Family Health Team

Office assistant (OA) calls parents of 18-month-olds before visit to remind them to come 15 min early.

OA gives parent the Nipissing District Developmental Screen (NDDS) on arrival at appointment.

Public health nurse (PHN) meets with parent(s) in the waiting room and assists them in completing the NDDS. PHN also reviews any parent concerns (re: child).

PHN may flag concerns to the primary care practitioner (PCP) before entering the examination room with the parent and child.

Parent and child see the PCP with the PHN using the physician prompt record (Ontario version of the Rourke Baby Record).

The PHN provides modelling and coaching content about nutrition, parenting, safety, dental hygiene, growth and development, and community resources as appropriate.

The PHN liaises with the PCP to discuss appropriate referrals and services relevant to client needs while the child is being immunized by the practice registered nurse.

After completion of immunization, the PCP offers parent referral suggestions, shares key literacy messages (scripted for the PCP), presents the parent with an appropriate book to read with their child, stressing the importance of frequent reading, and gives the parent a bookmark highlighting resources such as Ontario early years centres, libraries, public

health central intake parent talk information line and Speech Services Niagara.

APPENDIX 2

Early Child Development and Parenting Resource System

References

- 1.UNICEF. Child poverty in perspective: An overview of child wellbeing in rich countries. Innocenti Report Card 7, 2007. Florence: UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre. <http://www.unicef-irc.org/publications/pdf/rc7_eng.pdf> (Version current at October 27, 2008).

- 2.Offord DR. The importance of recreation for all children and youth. In: Leveling The Playing Field. Ottawa: Parks and Recreation Canada. 2002;60:14. [Google Scholar]

- 3.McCain MN, Mustard JF.Reversing the Real Brain Drain The Early Years Study, Final Report 1999 Toronto: Publications Ontario; 1999. <http://www.children.gov.on.ca/mcys/english/resources/publications/beststart-early.asp> (Version current at October 27, 2008). [Google Scholar]

- 4.McCain MN, Mustard JF, Shanker S.Early Years Study 2: Putting science into action TorontoCouncil for Early Child Development; <http://www.councilecd.ca/cecd/home.nsf/pages/eys2pdf> (Version current at October 27, 2008). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hubel DH, Wiesel TN. Binocular interaction in striate cortex of kittens reared with artificial squint. J Neurophysiol. 1965;28:1041–59. doi: 10.1152/jn.1965.28.6.1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Teicher MH. Scars that won’t heal: The neurobiology of child abuse. Sci Am. 2002;286:68–75. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican0302-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, et al. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am J Prev Med. 1998;14:245–58. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meaney Szyf. Learning without learning; Epigenetics. (Epigenetics may explain how childhood experience affects adult behaviour) The Economist. 2006;53:463–90. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heckman JJ.Policies to Foster Human Capital Joint Center for Poverty Research(Working Paper No. 154). Northwestern University/University of Chicago,2000

- 10.Dodge D. Human Capital, Early Childhood Development, and Economic Growth: An Economist’s Perspective. Sparrow Lake. 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grunewald R, Rolnick A. A proposal for Achieving High Returns on Early Childhood Development. Minneapolis: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schweinhart LJ, Barnes HV, Weikart DP. Lifetime Effects: The High/Scope Perry Preschool Study Through Age 40. Ypsilanti: High Scope Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wasek B, Ramey C, Bryant D, et al. A longitudinal study of two early intervention strategies: Project CARE. Child Dev. 1990;61:1682–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kirp D. The Sandbox Investment: The preschool movement and kids-first policy. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Olds DL, Kitzman H, Cole R, et al. Effects of nurse home-visiting on maternal life course and child development: Age 6 follow-up results of a randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2004;114:1550–9. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-0962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rutter M, Silberg J. Gene-environment interplay in relation to emotional and behavioural disturbance. Ann Rev Psychol. 2002;53:463–90. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lalonde M.A New Perspective on the Health of Canadians, a Working Document. Government of Canada,1981

- 18.Government of Ontario. Best Start <http://www.gov.on.ca/children/english/programs/beststart/index.html> (Version current at October 27, 2008).

- 19.Getting it Right at 18 Months…Making it Right for a Lifetime: Report of the Expert Panel on the Enhanced 18-Month Well Baby Visit. <www.cfpc.ca/local/files/CME/Research/FinalRpt-18MonthPrjct.pdf> (Version current at October 27, 2008).

- 20.Investing in Quality: Report of the Expert Panel on Quality and Human Resources. <http://www.gov.on.ca/children/english/resources/beststart/> (Version current at October 27, 2008).

- 21.Ontario’s Investments in Early Childhood Development Early Learning and Child Care 2005–2006. <http://www.gov.on.ca/children/english/resources/beststart/STEL02_179877.html > (Version current at October 27, 2008).

- 22.Final Report to the OCFP for the Evidence to Support the 18 Month Well Baby Visit. Recommendations developed by The 18 Month Steering Committee Facilitated by The Guidelines Advisory Committee (GAC). <http://www.ocfp.on.ca/local/files/CME/Healthy%20Child%20Development/18%20Month%20Well%20Baby%20Visit/Edits%20from%20OCFP-%20Final%20Report%20Oct%2026–07.pdf > (Version current at October 27, 2008).

- 23.Nipissing District Developmental Screen. <www.ndds.ca> (Version current at October 27, 2008).

- 24.The College of Family Physicians of Canada. Rourke Baby Record – Ontario version. <http://www.cfpc.ca/English/cfpc/programs/patient%20care/rourke%20baby/default.asp?s=1 > (Version current at October 27, 2008).

- 25.Reach Out and Read National Center. <www.reachoutandread.org> (Version current at October 27, 2008).

- 26.Canadian Paediatric Society, Psychosocial Paediatrics Committee [Principal Author: A Shaw]. Read, Speak and Sing to Your Baby. <http://www.cps.ca/> (Version current at October 27, 2008).

- 27.Golova N, Alario AJ, Vivier P, et al. Literacy promotion for hispanic families in a primary care setting: A randomized, controlled trial. Pediatrics. 1999;103:993–7. doi: 10.1542/peds.103.5.993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cohen NJ, Daum RS, Lauderdale DS, Seal JB, Shete PB. Physician knowledge of catch-up regimens and contraindications for childhood immunizations. Paediatrics. 2003;111:925–33. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.5.925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.The Regional Municipality of Niagara. <www.beagreatparent.ca> (Version current at October 27, 2008).

- 30.Ross LE, Dennis C-L, Robertson-Blackmore E, Stewart DE. Postpartum Depression: A Guide for Front-Line Health and Social Service Providers. Toronto: The Centre for Addiction and Mental Health; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reaching for the Top: A report by the Advisor on Healthy Children and Youth. <http://www.hs-sc.gc.ca> (Version current at October 27, 2008).