Abstract

Reproductive hormone secretions are inhibited by fasting and restored by feeding. Metabolic signals mediating these effects include fluctuations in serum glucose, insulin, and leptin. Because ATP-sensitive potassium (KATP) channels mediate glucose sensing and many actions of insulin and leptin in neurons, we assessed their role in suppressing LH secretion during food restriction. Vehicle or a KATP channel blocker, tolbutamide, was infused into the lateral cerebroventricle in ovariectomized mice that were either fed or fasted for 48 h. Tolbutamide infusion resulted in a twofold increase in LH concentrations in both fed and fasted mice compared with both fed and fasted vehicle-treated mice. However, tolbutamide did not reverse the suppression of LH in the majority of fasted animals. In sulfonylurea (SUR)1-null mutant (SUR1−/−) mice, which are deficient in KATP channels, and their wild-type (WT) littermates, a 48-h fast was found to reduce serum LH concentrations in both WT and SUR−/− mice. The present study demonstrates that 1) blockade of KATP channels elevates LH secretion regardless of energy balance and 2) acute fasting suppresses LH secretion in both SUR1−/− and WT mice. These findings support the hypothesis that KATP channels are linked to the regulation of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) release but are not obligatory for mediating the effects of fasting on GnRH/LH secretion. Thus it is unlikely that the modulation of KATP channels either as part of the classical glucose-sensing mechanism or as a component of insulin or leptin signaling plays a major role in the suppression of GnRH and LH secretion during food restriction.

Keywords: sulfonylurea, luteinizing hormone, gonadotropin-releasing hormone, metabolic signals

in most mammalian species, reproductive capacity is closely linked to the availability of oxidizable metabolic fuels (57, 73). A short-term fast or prolonged reduction in caloric intake suppresses the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis, as reflected by reduced LH secretion or disrupted ovulatory cyclicity in mice (2, 28, 68), hamsters (5), rats (7, 8, 46), sheep (23, 36), monkeys (16, 38), and humans (39, 44). Refeeding can rapidly reverse these effects (9, 16, 80). It is generally held that these reproductive responses to reduced energy intake are mediated by a deceleration or complete arrest of the pulsatile neurosecretion of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) (30). It remains unclear how neural, endocrine, and/or metabolic signals may be conveyed from peripheral tissues to the hypothalamic “GnRH pulse generator” to regulate reproductive activity in response to negative energy balance. Among the most likely candidates for these somatic signals are circulating oxidizable metabolites, such as glucose (12, 51, 59) and fatty acids (57, 63), as well as serum leptin (2, 27, 52, 58) and insulin (10, 13, 21, 37, 69) concentrations, which reflect prevailing levels of adiposity. Thus GnRH pulsatility may be sustained in positive energy balance by any one or all of these peripheral signals, while, conversely, a deceleration of GnRH pulse generator activity may be precipitated by fasting-induced decreases in one or more of them.

ATP-sensitive potassium (KATP) channels have been implicated as downstream cellular effectors of several of the foregoing metabolic signals, including glucose (3, 41, 47), leptin (48, 66), and insulin (48, 67). The channels comprise a complex of four each of two protein subunits, the pore-forming Kir6.x subunit and the sulfonylurea (SUR) regulatory subunit. There are two isoforms of the SUR subunit, SUR1 and SUR2; subunits Kir6.2 and SUR1 make up channels found in both pancreas and brain (32, 33, 62, 64). These channels are particularly prevalent in neuropeptide Y (NPY)/agouti-related peptide (AgRP) (22, 45, 72) and proopiomelanocortin (POMC) (31, 54) neurons of the arcuate and ventromedial nuclei, where they have been shown to mediate a glucose-sensing function (31, 72), as well as responses to insulin and leptin (41, 48, 72). Notably, subsets of these same neuronal groups project to GnRH neurons and regulate their secretory activity (40, 42). The KATP channels that could mediate metabolic inhibition of GnRH secretion may also be those that are expressed in GnRH neurons themselves, as our collaborators and we have recently characterized (79). Similarly, the Kir6.2/SUR1-containing KATP channels are expressed in glucose-sensing brain stem neurons (20, 22) that may mediate glucoprivic suppression of GnRH release (17, 50) and estrous cyclicity (60), as well as glucoprivic feeding and homeostatic control of blood glucose (56). Neuroanatomic studies also provide relevant evidence that neurons in the hindbrain send projections to the GnRH neurons (71) and affect GnRH/LH secretion (15, 18). The KATP channels are thus positioned to mediate glucoprivic regulation of GnRH release at both neural loci.

The foregoing observations suggest that KATP channel modulation in glucose-sensing hypothalamic or brain stem neurons may mediate the suppressive effects of negative energy balance on GnRH and LH secretions. According to this hypothesis, prolonged reduction in circulating glucose concentrations would lead to activation of KATP channels and reduced excitability in the neuronal circuitries that govern GnRH neurosecretion. A variant of this hypothesis holds that fasting-induced reductions in leptin or insulin lead to reduced KATP channel activation, presumably heightening excitability in POMC neurons or other cell populations that exert inhibitory control over GnRH neurons. In the present studies, we tested the general hypothesis that KATP channel modulation mediates fasting-induced GnRH suppression by either or both of these mechanisms. To do this, we assessed the effects of pharmacological blockade of KATP channels, as well as deletion of the gene for the SUR1 KATP channel subunit, on fasting-induced suppression of LH secretion. We predicted that the blockade of KATP channels would reverse, while KATP channel elimination would prevent, any fasting-induced decline in LH concentrations. Surprisingly, our results clearly demonstrate that fasting can suppress LH, and presumably GnRH secretion, independently of KATP channel activation. These observations effectively rule out an obligatory role for the classic glucose-sensing mechanism, as well as KATP channel-mediated insulin or leptin signaling, in the inhibitory effects of negative energy balance on GnRH and LH secretion.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Female C57BL/6 mice (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA) were used in experiment 1, while age-matched isogenic adult wild-type (WT) and SUR1−/− female mice were used in experiment 2. SUR1−/− male and female mice (C57BL/6 × 129 SvJ) were generously provided by Dr. Mark A. Magnuson (Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN) (65). Matings of male SUR1−/− or C57BL/6 mice with SUR1−/− female mice failed to produce viable offspring. Although vaginal plugs were observed after pairing, indicating that mating had occurred, few pups were born, and in the litters born the number of pups per litter was small and the pups died shortly after birth. Therefore male SUR1−/− mice were mated to female C57BL/6 mice to generate heterozygous SUR1-knockout mice. Subsequent matings of the heterozygous SUR1-knockout mice were then used to produce both WT and SUR1−/− mice. All animals were housed in temperature-controlled facilities (23–25°C) with a 12:12-h light-dark cycle (0500–1700). The animals were fed standard laboratory chow and had access to water ad libitum. All surgical and experimental procedures were performed in strict accordance with protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Northwestern University.

Experiment 1: Effects of Intracerebroventricular Tolbutamide Infusion on LH Secretion in Fed and Fasted Female Mice

On day 0, the animals were anesthetized with ketamine (80 mg/kg ip; Fort Dodge Laboratories, Fort Dodge, IA) and xylazine (32 mg/kg ip; Burns Veterinart Supply, Rockville Center, NY) and bilaterally ovariectomized (OVX). At the same time, all animals received guide cannulas fitted with obdurators (CMA/7 guide cannulas; CMA Microdialysis, North Chelmsford, MA); stereotaxic surgical techniques were used to target the guide cannulas to the right lateral ventricle (coordinates 0.2 mm caudal to bregma, 2.0 mm ventral to the skull, 1.0 mm lateral) (53). Five days later, a subset of the mice were fasted, while the rest received food ad libitum. All animals had free access to water. Forty-eight hours after fasting, all animals were briefly anesthetized by isoflurane inhalation and an infusion cannula was fitted into the guide cannula. After insertion, either vehicle [0.1% DMSO in artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF)] or tolbutamide (500 μM in 0.1% DMSO) was infused through the cannula at a rate of 1 μl/min for 2 min (equal to total dose of 270 ng tolbutamide). The components of aCSF were (in mM) 124 NaCl, 5 KCl, 26 NaHCO3, 2.6 NaH2PO4, 10 dextrose, 10 HEPES, 2 MgSO4, and 2 CaCl2. After infusion, the probe was maintained in place for one additional minute and then replaced with the obdurator. Four minutes later, the animals were anesthetized by CO2 inhalation, and terminal blood samples were collected by cardiac puncture and centrifuged at 13,000 rpm at 4°C for 10 min. Blood samples also were collected from an additional group of fasted animals 25 min after tolbutamide infusion. This time course was selected because bolus injection of tolbutamide induces a transient elevation in insulin secretion that peaks within 4 min and returns to baseline within 20 min (11). Plasma was then harvested and stored at −20°C for subsequent LH radioimmunoassays (RIAs). All animals were weighed on day 5 immediately before being fasted, on day 6 during fasting, and on day 7 before they were euthanized.

Experiment 2: Effects of 48 h of Fasting on LH Secretion in Female SUR1-Knockout Mice

On day 0, both WT and SUR1−/− mice were anesthetized by isoflurane inhalation (Baxter, Deerfield, IL) and underwent bilateral OVX. Ovaries were weighed, and initial body weight was recorded. Five days later, all animals were again briefly anesthetized by isofluorane inhalation and 80–100 μl of blood was collected by tail venipuncture. Blood glucose concentrations were measured with a Prestige Smart System Glucose Monitor (Home Diagnostics, Fort Lauderdale, FL). Blood samples were centrifuged, and plasma was stored at −20°C for subsequent LH RIAs. On completion of tail blood collection, food was removed from the SUR1−/− (n = 10) and WT (n = 11) animals to initiate the fast. During fasting, the animals received water ad libitum. An additional group of nine WT animals continued to receive food during this time. After 48 h of fasting, the animals were anesthetized by CO2 inhalation and killed by cervical dislocation. Blood samples were collected by cardiac puncture, and again blood glucose concentrations were determined. Plasma was obtained from this second set of samples and stored at −20°C for LH, insulin, and leptin RIAs. Bilateral uterine tissues were removed and weighed. All the animals were weighed on day 5 immediately before being fasted, on day 6 during fasting, and on day 7 before they were killed.

Hormone Assays

Plasma LH concentrations were determined by RIA using reagents obtained from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, including LH reference (RP-3) and anti-rat LH antibody (S-11). The assay had a lower limit of detection of 0.2 ng/ml. The intra-assay and interassay coefficients of variation (CVs) for LH assays were 7.6% and 11.5%, respectively. Leptin was measured with the Rat Leptin RIA Kit from Linco Research (catalog no. RL-83K, St. Charles, MO). This kit shows 100% cross-reactivity with mouse leptin; serial dilution curves of rat and mouse sera run in our laboratory are parallel. The sensitivity of the leptin assay is 0.5 ng/ml. Insulin assays were conducted with the Sensitive Rat Insulin RIA from Linco Research (catalog no. SRI-13K); this kit has a sensitivity of 0.2 ng/ml. This kit shows 100% cross-reactivity with mouse insulin; serial dilution curves of rat and mouse sera run in our laboratory are parallel. The intra-assay CVs for leptin and insulin assays were 1.48% and 2.7%, respectively.

Statistical Analysis

All summary data are presented as means ± SE. The effects of intracerebroventricular (ICV) vehicle or tolbutamide infusion on LH concentrations in fed and fasted mice were assessed by two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's multiple-comparison post hoc tests (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA).

Comparisons of body weight and LH and glucose concentrations before and after 48 h of fasting in WT and SUR1−/− mice were performed by two-way ANOVA with repeated measures followed by Bonferroni's multiple-comparison post hoc test (GraphPad Software). Ovary weight before fasting, and uterine weight, leptin concentrations, insulin concentrations, and glucose-to-insulin ratio after fasting were compared between WT and SUR1−/− mice by unpaired t-tests. For all statistical analysis, significant differences were reported at P ≤ 0.05.

RESULTS

Experiment 1: Effect of ICV Tolbutamide on LH Secretion in Fed and Fasted Female Mice

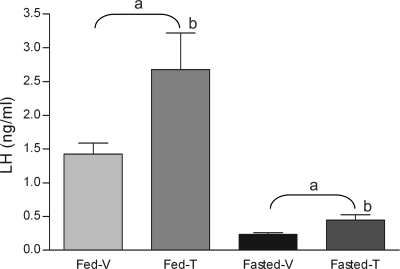

LH levels were dramatically decreased in fasted animals (ANOVA: fed vs. fasted, P < 0.001) (Fig. 1). Infusion of tolbutamide into the lateral ventricle stimulated similar fold increases in serum LH concentrations in the fed and fasted groups (ANOVA: vehicle vs. tolbutamide, P = 0.01). Although infusion of tolbutamide stimulated a nearly twofold increase in LH secretion in fasted animals (0.23 ± 0.03 ng/ml for vehicle vs. 0.45 ± 0.08 ng/ml for tolbutamide, P < 0.05) (Fig. 1), it did not elevate the LH concentrations of fasted mice to those of fed mice treated with vehicle. Similarly, tolbutamide infusion also stimulated a twofold increase in plasma LH concentrations in the fed mice (1.43 ± 0.16 ng/ml for vehicle vs. 2.68 ± 0.64 ng/ml for tolbutamide, P < 0.05). The release of LH in response to tolbutamide in both the fed and fasted groups was rapid; the increases occurred within 4 min after infusion of the drug. There did not appear to be any additional increase in LH secretion after tolbutamide infusion because serum concentrations collected from a separate group of fasted animals 25 min after tolbutamide infusion (mean ± SE: 0.32 ± 0.05 ng/ml, n = 11) were not significantly different from concentrations observed at 4 min (mean ± SE: 0.45 ± 0.08, n = 15) (P = 0.27).

Fig. 1.

Response of LH secretion to intracerebroventricular tolbutamide (500 μM) or vehicle (0.1% DMSO) infusion in fed and 48-h-fasted female mice. There were 8, 10, 9, and 15 mice in fed and vehicle-infused (Fed-V), fed and tolbutamide-infused (Fed-T), fasted and vehicle-infused (Fasted-V), and fasted and tolbutamide-infused (Fasted-T) groups, respectively. Tolbutamide infusion into the lateral ventricle significantly increased LH concentrations in both fed and 48-h-fasted female mice. aFasting had a significant effect among groups (P < 0.001); btolbutamide had a significant effect (P < 0.01).

Experiment 2: Effect of 48 h of Fasting in WT and SUR1−/− Female Mice

Body and tissue weights.

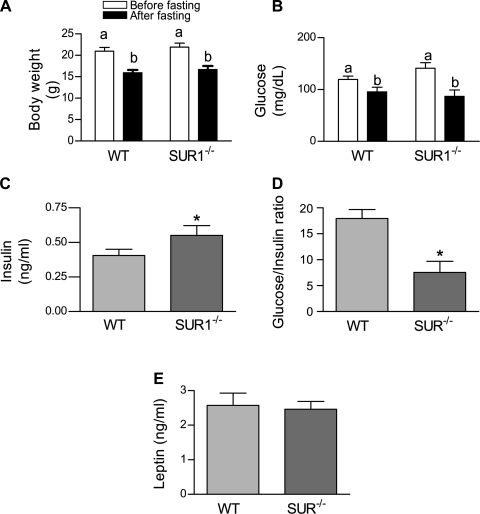

There was no significant difference in initial body weight between WT and SUR1−/− female mice. The 48-h fast caused similar and significant weight loss in both WT and SUR1−/− mice (20.96 ± 0.88 g before fasting vs. 15.93 ± 0.68 g after fasting in WT mice; 21.94 ± 0.92 g before fasting vs. 16.69 ± 0.82 g after fasting in SUR1−/−mice) (Fig. 2A) (ANOVA: before vs. after, P < 0.001). The weights of ovaries before fasting and the weights of uteri postmortem did not differ between the WT and SUR1−/− mice (Table 1).

Fig. 2.

Effects of a 48-h fast on metabolic characteristics of wild-type (WT) and sulfonylurea (SUR)−/− mice. A: fasting significantly reduced body weight in both genotypes (2-way ANOVA with repeated measures, P < 0.001); n = 11 (WT) and 10 (SUR1−/−). Groups with the same letter do not differ. There was no significant effect of genotype or the interaction between food manipulation and genotype on body weight. B: fasting significantly reduced serum glucose levels in both genotypes (2-way ANOVA with repeated measures, P < 0.0001). However, there was no significant effect of either genotype or the interaction between food manipulation and genotype. C: insulin concentrations were significantly higher in SUR1−/− mice than in WT mice after 48-h fast (*P = 0.04). D: glucose-to-insulin ratio of SUR1−/− mice was significantly lower than that of WT mice after the 48-h fast (*P < 0.02); n = 11 (WT) and 10 (SUR1−/−). E: leptin concentrations after fasting did not differ between WT and SUR1−/− female mice after 48-h fast. Groups with the same letter do not differ.

Table 1.

Ovarian weights before fasting and uterine weights after fasting in wild-type and SUR1−/− female mice

| Wild Type | SUR1−/− | Statistics | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ovary weight before fasting, mg | 12.18±0.65 | 12.10±1.03 | NS |

| Uterine weight after fasting, mg | 36.64±3.79 | 32.85±2.40 | NS |

Values are means ± SE. NS, not significant.

Glucose concentrations.

Fasting resulted in a significant decline in serum glucose (ANOVA: fed vs. fasted, P < 0.001) (Fig. 2B). There was no significant effect of genotype on serum glucose concentrations (ANOVA: genotype, P = 0.57).

Insulin concentrations, glucose-to-insulin ratio, and leptin concentrations after fasting.

After 48 h of fasting, insulin concentrations were significantly higher in SUR1−/− mice than in WT mice (0.37 ± 0.04 ng/ml and 0.59 ± 0.07 ng/ml in WT and SUR1−/−, respectively, P = 0.04; Fig. 2C), while the glucose-to-insulin ratio in SUR1−/− mice was significantly lower than that in WT mice (16.7 ± 1.88 and 7.46 ± 1.81 of WT and SUR1−/−, respectively, P = 0.02; Fig. 2D). However, leptin concentrations were not significantly different between the two genotypes (P = 0.80; Fig. 2E).

LH concentrations.

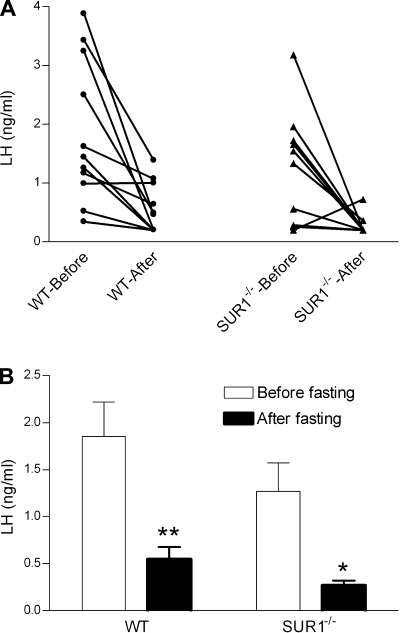

LH concentrations before and after fasting in each individual animal are depicted in Fig. 3A. Basal LH concentrations before fasting did not differ between WT and SUR1−/− mice. Fasting significantly reduced serum LH levels (ANOVA, P < 0.001) independently of genotype (ANOVA, P = 0.54). The reduction of LH in both genotypes after 48 h of fasting compared with the prefast levels was significant by post hoc multiple comparisons (1.85 ± 0.37 ng/ml before fasting vs. 0.55 ± 0.13 ng/ml after fasting in WT mice, P < 0.01; 1.27 ± 0.30 ng/ml before fasting vs. 0.27 ± 0.05 ng/ml after fasting in SUR1−/− mice, P < 0.05; Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

LH concentrations in WT and SUR1−/− female mice before and after fasting. A: LH concentrations in each individual animal before and after fasting were plotted and connected by lines (WT, n = 11; SUR1−/−, n = 10). B: LH concentrations in WT and SUR1−/− female mice before and after fasting. Two-way ANOVA with repeated measures found a significant effect of food manipulation on LH concentrations. Bonferroni's post hoc test revealed that 48 h of fasting significantly reduced LH concentrations in both WT (**P < 0.01) and SUR1−/− (*P < 0.05) mice. There was no significant effect of genotype or the interaction between food manipulation and genotype.

DISCUSSION

It is generally held that inhibition of gonadotropin secretion in response to negative energy balance is a consequence of the suppression of pulsatile GnRH release (30), because food deprivation and refeeding have been shown to cause deceleration and reacceleration of LH pulsatility, respectively (8, 69). Because pulsatile LH secretion can be modulated within hours of food restriction or refeeding, it has been hypothesized that the GnRH pulse generator is sensitive to circulating metabolic signals that directly or indirectly reflect the availability of oxidizable metabolic fuels (57, 73). Among the most likely of these metabolic cues are serum glucose, leptin, and insulin, which are all reduced during food restriction and restored to original levels after refeeding. All three of these factors, glucose, leptin, and insulin, modulate KATP channel activity in neurons that are known to regulate GnRH pulsatility; therefore, we sought to determine whether KATP channel modulation mediates the effects of food restriction on GnRH release, as reflected by surrogate measurements of serum LH. Although we have recently confirmed (79) that KATP channel modulation can regulate LH secretion and presumably GnRH release in the OVX mouse, our findings reveal that the suppressive effects of food restriction on LH release do not require the expression of SUR1, the isoform of regulatory protein that is expressed in glucose-sensing neurons of the hypothalamus and brain stem (4, 43, 47) and required for central glucoregulatory responses to insulin (55). By subjecting the mice to a 48-h fast, we induced an ∼25% reduction in body weight and a 20–38% reduction in blood glucose levels. Although these reductions in blood glucose levels are not as great as those reported in some studies (24, 25), they were associated with a significant loss of body weight and reduction in LH secretion. Contrary to our hypothesis, treatment with tolbutamide did not override the fasting-induced suppression of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis and restore LH secretion to the levels found in fed animals. In contrast, we determined that blockade of KATP channels with tolbutamide produces similar percentage increases in serum LH concentrations regardless of whether animals are fed or fasted, arguing against the idea that activated KATP channels maintain the fasting-induced suppression of GnRH/LH. Thus, if fasting-induced reductions in glucose, insulin, and/or leptin do lead to reduced GnRH pulsatility, then the mechanisms responsible for any such effects appear not to involve the activation of KATP channel signaling pathways.

Previous studies in sheep (12) and rats (51) showed that central glucoprivation, induced by ICV infusion of the glucose antimetabolite 2-deoxyglucose, can rapidly reduce GnRH pulsatility. These findings suggested that the hypothalamic GnRH pulse generator is sensitive to inhibition during hypoglycemia and raised the possibility that diminished extracellular glucose concentrations during food restriction may be transduced as a metabolic cue for suppression of GnRH pulsatility. Fluctuations in extracellular glucose concentrations have been known for many years to be registered by glucose-responsive neurons and transduced into alterations in electrophysiological activity (41). In many glucose-sensing neurons, particularly those that are excited when exposed to higher levels of glucose, the uptake and oxidation of glucose produces an increase in the intracellular ATP-to-ADP ratio, which in turn prompts binding of ATP to KATP channels in the plasma membrane and blockade of the channel pore. The KATP channels thereby link the cellular metabolism of glucose to alterations in neuronal excitability in glucose-responsive neurons (1), and this may serve as one mechanism by which fasting-associated reductions in serum glucose may be registered and transduced into reduced neurosecretion of GnRH. In support of this idea, it was recently reported that the presumed reduction in glucose oxidation in heterozygous glucokinase-knockout mice is associated with impaired reproductive function (78). Moreover, GnRH neurons express KATP channels and are glucose sensitive (79), as are POMC (34, 54) and NPY (22, 45, 72) neurons, the latter neuronal populations forming a portion of afferent circuitries controlling GnRH release (6, 28, 35, 75). The present studies, however, provide evidence that food restriction leads to a suppression of LH secretion independently of KATP channel modulation.

Our data suggest that the classic glucose-sensing mechanism is not an obligatory component of the mechanisms that mediate fasting-induced suppression of reproductive hormone secretion. It remains possible that KATP channel-mediated glucose sensing operates as one of many redundant mechanisms, or alternatively that fluctuations in glucose availability and metabolism are registered and transduced in a KATP-independent manner to suppress GnRH release. It is also possible that KATP channels can mediate hypoglycemic suppression of GnRH pulsatility but that this mechanism is only triggered in response to more severe hypoglycemic stress than that produced by our food restriction protocol. A neuroprotective function has been ascribed to KATP channels in other neuronal populations that are not known to be glucose responsive under euglycemic conditions (76).

The KATP channels also mediate some of the effects of insulin and leptin in hypothalamic and arcuate neurons (48, 66, 67). Both hormones, in part, modulate phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (74) to prompt changes in KATP channel activity, with the direction of these effects depending upon the cell context. Reproductive hormone secretions and ovulatory cyclicity are impaired in mice deficient in leptin (19), leptin receptor (68), brain insulin receptors (10), and insulin receptor substrate (IRS)-2 (14). In metabolically challenged rodents, a drop in peripheral leptin concentrations occurs that is accompanied by a deceleration of LH pulsatility, and administration of leptin can stimulate LH pulsatility in these animals (2, 58) and sheep (26, 27). Similarly, insulin concentrations fall during food restriction (52), and in at least one study insulin treatment was found to stimulate pulsatile LH secretion (70). Moreover, insulin concentrations rise in refed animals before the restoration of pulsatile LH secretion (69), implicating endogenous insulin as a permissive signal for the maintenance of basal GnRH pulsatility.

Consistent with previous observations, we observed that leptin concentrations tended to be reduced in fasted animals of both genotypes. We measured leptin and insulin at the termination of the experiment to determine the status of the hormones as a result of the 48-h fast but were unable to obtain sufficient serum to measure leptin and insulin from the same animals before and after fasting. At the time the fasted animals were killed, blood was collected from a separate group of age-matched WT mice that had undergone similar surgical procedures to provide baseline data from fed animals from our colony, but additional SUR−/− animals were not available. Leptin levels appeared to decline slightly in the fasted WT animals compared with the fed WT animals, although the effect was not significant (fed 3.4 ± 0.4 ng/ml vs. fasted 2.6 ± 0.9 ng/ml; P = 0.07, 1-tailed t-test). Because the leptin levels of the fasted WT and SUR−/− mice did not differ, it is plausible that the leptin levels of the SUR−/− mice had also declined. Insulin concentrations similarly trended downward in fasted WT animals (fed 0.51 ± 0.31 ng/ml vs. fasted 0.41 ± 0.11 ng/ml; P = 0.21, 1-tailed t-test). Forty-eight hours after fasting, insulin concentrations in SUR1−/− mice were significantly higher than those in fasted WT mice; this was expected because this genotype was previously shown to be mildly hyperinsulinemic under fasting conditions (61). Unfortunately, insufficient numbers of SUR−/− mice were available to provide an equivalent fed group. These data indicate that, irrespective of the presence or absence of alterations in leptin or insulin, fasting produced significant declines in serum LH concentrations in both genotypes. Because LH concentrations fell to an equal extent in both WT and SUR−/− mice, it is reasonable to conclude that KATP channels are not necessary to communicate the diminishment of insulin or leptin concentrations to neurons governing the neurosecretion of GnRH. It is possible that the absence throughout development of the SUR1 subunit in the SUR−/− mice from the numerous neuronal phenotypes involved in nutrient sensing resulted in compensatory adaptations leading to these observations.

We observed that ICV infusion of tolbutamide produced a doubling of LH concentrations over baseline concentrations in fed mice, as well as a twofold increase over the diminished LH concentrations produced by the 48-h fast. The increase in circulating LH concentrations occurred by the time the blood samples were collected 4 min after infusion of tolbutamide. It could be argued that the fasted animals simply required additional time to respond to tolbutamide and release LH. This appears not to be the case. Additional data were collected from a separate set of fasted animals 25 min after infusion of tolbutamide. The LH concentrations of fasted animals did not continue to increase and appeared to have begun to wane by this time. In this respect, the pharmacokinetics of tolbutamide are similar to those of KATP channel-associated insulin secretion (11). These findings suggest that fasting is not associated with any overt change in the number or functional state of KATP channels that directly or indirectly modulate GnRH release.

Although these results are not consistent with a role for KATP channel modulation in the suppression of LH by fasting, they do nevertheless confirm that KATP channels are functionally linked to the GnRH neurosecretory process. Similarly, we and our collaborators have recently demonstrated (79) that GnRH neurons themselves express KATP channels that are responsive to metabolic inhibition and fluctuations in extracellular glucose; in that study, the ionic currents observed during KATP channel activation were greater in tissues harvested from estrogen-treated mice. We have also observed that estrogen and progesterone treatments enhance the stimulatory actions of ICV tolbutamide on LH pulsatility in OVX rats (29), while the combined treatment with these steroids maximally stimulates Kir6.2 mRNA expression in the preoptic area. It is thus possible that KATP channels may play a more important physiological role in mediating steroid hormone feedback actions on GnRH neurons or their afferents than in signaling low energy availability to the reproductive axis.

The modulation of GnRH secretion by KATP channels, as demonstrated previously (79) and inferred from the present work, may also serve a neuroprotective role. In other neuronal populations, such as Kir6.2/SUR1-expressing neurons in the substantia nigra, KATP channels appear to restrain hypoxia-induced seizure propagation (77). The substantia nigra is critically important in controlling the propagation of generalized seizures, and opening of KATP channels in nigral neurons strongly suppresses neuronal activity during hypoxic challenge. Findings in Kir6.2-null mutant mice (77) as well as in SUR1-null mutants (49) also clearly demonstrate that the β-cell type KATP channels play critically important roles in raising the thresholds for seizure initiation and propagation induced by metabolic insufficiency or excitotoxic insult (76). It is not clear whether GnRH neurons, or the neurons that comprise their afferent circuitries, are especially vulnerable to hypoxic, hypoglycemic, and/or excitotoxic stress, and thus the importance of any such neuroprotective mechanism remains to be clarified.

The present observations suggest that the suppression of LH secretion during fasting does not depend on KATP channel-mediated glucose sensing or the modulation of KATP channel activity by insulin, leptin, or other metabolic cues. The physiological and cellular mechanisms that mediate the reproductive hormonal response to food restriction thus remain unknown. All of the foregoing cues, glucose, leptin, and insulin, remain viable candidates as signals for suppression of LH secretion; however, their actions would appear to be mediated by KATP channel-independent pathways. It also remains possible, if not likely, that food restriction simultaneously prompts fluctuations in several of these and other circulating metabolic cues, as well as alterations in ascending neural signals, and that this convergent information is transduced and summed within the neural systems that govern GnRH pulsatility. Thus summation of these signals may then collectively surpass some critical cellular threshold for the suppression of the GnRH pulse-generating mechanism. Nevertheless, our findings reveal that KATP channel modulation is not an obligatory component of this integrative response to a metabolic challenge.

GRANTS

The work reported in this article was supported by National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Grants R01-HD-20677 and P50-HD-44405.

Acknowledgments

We thank Brigitte Mann for conducting all hormone assays reported in this article.

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. The article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aguilar-Bryan L, Bryan J. Molecular biology of adenosine triphosphate-sensitive potassium channels. Endocr Rev 20: 101–135, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahima RS, Prabakaran D, Mantzoros C, Qu D, Lowell B, Maratos-Flier E, Flier JS. Role of leptin in the neuroendocrine response to fasting. Nature 382: 250–252, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ashford ML, Boden PR, Treherne JM. Tolbutamide excites rat glucoreceptive ventromedial hypothalamic neurones by indirect inhibition of ATP-K+ channels. Br J Pharmacol 101: 531–540, 1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balfour RH, Hansen AM, Trapp S. Neuronal responses to transient hypoglycaemia in the dorsal vagal complex of the rat brainstem. J Physiol 570: 469–484, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berriman SJ, Wade GN, Blaustein JD. Expression of Fos-like proteins in gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons of Syrian hamsters: effects of estrous cycles and metabolic fuels. Endocrinology 131: 2222–2228, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Besecke LM, Wolfe AM, Pierce ME, Takahashi JS, Levine JE. Neuropeptide Y stimulates luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone release from superfused hypothalamic GT1–7 cells. Endocrinology 135: 1621–1627, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bronson FH Effect of food manipulation on the GnRH-LH-estradiol axis of young female rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 254: R616–R621, 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bronson FH Food-restricted, prepubertal, female rats: rapid recovery of luteinizing hormone pulsing with excess food, and full recovery of pubertal development with gonadotropin-releasing hormone. Endocrinology 118: 2483–2487, 1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brooks AN, Lamming GE, Lees PD, Haynes NB. Opioid modulation of LH secretion in the ewe. J Reprod Fertil 76: 693–708, 1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bruning JC, Gautam D, Burks DJ, Gillette J, Schubert M, Orban PC, Klein R, Krone W, Muller-Wieland D, Kahn CR. Role of brain insulin receptor in control of body weight and reproduction. Science 289: 2122–2125, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bruns CM, Baum ST, Colman RJ, Eisner JR, Kemnitz JW, Weindruch R, Abbott DH. Insulin resistance and impaired insulin secretion in prenatally androgenized male rhesus monkeys. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 89: 6218–6223, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bucholtz DC, Vidwans NM, Herbosa CG, Schillo KK, Foster DL. Metabolic interfaces between growth and reproduction. V. Pulsatile luteinizing hormone secretion is dependent on glucose availability. Endocrinology 137: 601–607, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burcelin R, Thorens B, Glauser M, Gaillard RC, Pralong FP. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone secretion from hypothalamic neurons: stimulation by insulin and potentiation by leptin. Endocrinology 144: 4484–4491, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burks DJ, Font de Mora J, Schubert M, Withers DJ, Myers MG, Towery HH, Altamuro SL, Flint CL, White MF. IRS-2 pathways integrate female reproduction and energy homeostasis. Nature 407: 377–382, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cagampang FR, Ohkura S, Tsukamura H, Coen CW, Ota K, Maeda K. Alpha 2-adrenergic receptors are involved in the suppression of luteinizing hormone release during acute fasting in the ovariectomized estradiol-primed rats. Neuroendocrinology 56: 724–728, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cameron JL, Nosbisch C. Suppression of pulsatile luteinizing hormone and testosterone secretion during short term food restriction in the adult male rhesus monkey (Macaca mulatta). Endocrinology 128: 1532–1540, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cates PS, O'Byrne KT. The area postrema mediates insulin hypoglycaemia-induced suppression of pulsatile LH secretion in the female rat. Brain Res 853: 151–155, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Catzeflis C, Pierroz DD, Rohner-Jeanrenaud F, Rivier JE, Sizonenko PC, Aubert ML. Neuropeptide Y administered chronically into the lateral ventricle profoundly inhibits both the gonadotropic and the somatotropic axis in intact adult female rats. Endocrinology 132: 224–234, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chehab FF A broader role for leptin. Nat Med 2: 723–724, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dallaporta M, Perrin J, Orsini JC. Involvement of adenosine triphosphate-sensitive K+ channels in glucose-sensing in the rat solitary tract nucleus. Neurosci Lett 278: 77–80, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.DiVall SA, Radovick S, Wolfe A. Egr-1 binds the GnRH promoter to mediate the increase in gene expression by insulin. Mol Cell Endocrinol 270: 64–72, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dunn-Meynell AA, Rawson NE, Levin BE. Distribution and phenotype of neurons containing the ATP-sensitive K+ channel in rat brain. Brain Res 814: 41–54, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Foster DL, Olster DH. Effect of restricted nutrition on puberty in the lamb: patterns of tonic luteinizing hormone (LH) secretion and competency of the LH surge system. Endocrinology 116: 375–381, 1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gavrilova O, Leon LR, Marcus-Samuels B, Mason MM, Castle AL, Refetoff S, Vinson C, Reitman ML. Torpor in mice is induced by both leptin-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96: 14623–14628, 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gray S, Wang B, Orihuela Y, Hong EG, Fisch S, Haldar S, Cline GW, Kim JK, Peroni OD, Kahn BB, Jain MK. Regulation of gluconeogenesis by Krüppel-like factor 15. Cell Metab 5: 305–312, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Henry BA, Goding JW, Tilbrook AJ, Dunshea FR, Blache D, Clarke IJ. Leptin-mediated effects of undernutrition or fasting on luteinizing hormone and growth hormone secretion in ovariectomized ewes depend on the duration of metabolic perturbation. J Neuroendocrinol 16: 244–255, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Henry BA, Goding JW, Tilbrook AJ, Dunshea FR, Clarke IJ. Intracerebroventricular infusion of leptin elevates the secretion of luteinising hormone without affecting food intake in long-term food-restricted sheep, but increases growth hormone irrespective of bodyweight. J Endocrinol 168: 67–77, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hill JW, Levine JE. Abnormal response of the neuropeptide Y-deficient mouse reproductive axis to food deprivation but not lactation. Endocrinology 144: 1780–1786, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huang W, Acosta-Martinez M, Levine JE. Ovarian steroids stimulate adenosine triphosphate-sensitive potassium (KATP) channel subunit gene expression and confer responsiveness of the gonadotropin-releasing hormone pulse generator to KATP channel modulation. Endocrinology 149: 2423–2432, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.I'Anson H, Manning JM, Herbosa CG, Pelt J, Friedman CR, Wood RI, Bucholtz DC, Foster DL. Central inhibition of gonadotropin-releasing hormone secretion in the growth-restricted hypogonadotropic female sheep. Endocrinology 141: 520–527, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ibrahim N, Bosch MA, Smart JL, Qiu J, Rubinstein M, Ronnekleiv OK, Low MJ, Kelly MJ. Hypothalamic proopiomelanocortin neurons are glucose responsive and express KATP channels. Endocrinology 144: 1331–1340, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Inagaki N, Gonoi T, Clement JP, Wang CZ, Aguilar-Bryan L, Bryan J, Seino S. A family of sulfonylurea receptors determines the pharmacological properties of ATP-sensitive K+ channels. Neuron 16: 1011–1017, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Inagaki N, Gonoi T, Clement JP, Namba N, Inazawa J, Gonzalez G, Aguilar-Bryan L, Seino S, Bryan J. Reconstitution of IKATP: an inward rectifier subunit plus the sulfonylurea receptor. Science 270: 1166–1170, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Iqbal J, Kurose Y, Canny B, Clarke IJ. Effects of central infusion of ghrelin on food intake and plasma levels of growth hormone, luteinizing hormone, prolactin, and cortisol secretion in sheep. Endocrinology 147: 510–519, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Karahalios DG, Levine JE. Naloxone stimulation of in vivo LHRH release is not diminished following ovariectomy. Neuroendocrinology 47: 504–510, 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kile JP, Alexander BM, Moss GE, Hallford DM, Nett TM. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone overrides the negative effect of reduced dietary energy on gonadotropin synthesis and secretion in ewes. Endocrinology 128: 843–849, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim HJ, Lee S, Kim TW, Kim HH, Jeon TY, Yoon YS, Oh SW, Kwak H, Lee JG. Effects of exercise-induced weight loss on acylated and unacylated ghrelin in overweight children. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 68: 416–422, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lado-Abeal J, Robert-McComb JJ, Qian XP, Leproult R, Van Cauter E, Norman RL. Sex differences in the neuroendocrine response to short-term fasting in rhesus macaques. J Neuroendocrinol 17: 435–444, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Laughlin GA, Yen SS. Nutritional and endocrine-metabolic aberrations in amenorrheic athletes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 81: 4301–4309, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Leranth C, MacLusky NJ, Shanabrough M, Naftolin F. Immunohistochemical evidence for synaptic connections between pro-opiomelanocortin-immunoreactive axons and LH-RH neurons in the preoptic area of the rat. Brain Res 449: 167–176, 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Levin BE Glucosensing neurons do more than just sense glucose. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 25: S68–S72, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li C, Chen P, Smith MS. Morphological evidence for direct interaction between arcuate nucleus neuropeptide Y (NPY) neurons and gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons and the possible involvement of NPY Y1 receptors. Endocrinology 140: 5382–5390, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liss B, Bruns R, Roeper J. Alternative sulfonylurea receptor expression defines metabolic sensitivity of K-ATP channels in dopaminergic midbrain neurons. EMBO J 18: 833–846, 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Loucks AB, Heath EM. Dietary restriction reduces luteinizing hormone (LH) pulse frequency during waking hours and increases LH pulse amplitude during sleep in young menstruating women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 78: 910–915, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lynch RM, Tompkins LS, Brooks HL, Dunn-Meynell AA, Levin BE. Localization of glucokinase gene expression in the rat brain. Diabetes 49: 693–700, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Manning JM, Bronson FH. Suppression of puberty in rats by exercise: effects on hormone levels and reversal with GnRH infusion. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 260: R717–R723, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Miki T, Liss B, Minami K, Shiuchi T, Saraya A, Kashima Y, Horiuchi M, Ashcroft F, Minokoshi Y, Roeper J, Seino S. ATP-sensitive K+ channels in the hypothalamus are essential for the maintenance of glucose homeostasis. Nat Neurosci 4: 507–512, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mirshamsi S, Laidlaw HA, Ning K, Anderson E, Burgess LA, Gray A, Sutherland C, Ashford ML. Leptin and insulin stimulation of signalling pathways in arcuate nucleus neurones: PI3K dependent actin reorganization and KATP channel activation. BMC Neurosci 5: 54, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Munoz A, Nakazaki M, Goodman JC, Barrios R, Onetti CG, Bryan J, Aguilar-Bryan L. Ischemic preconditioning in the hippocampus of a knockout mouse lacking SUR1-based KATP channels. Stroke 34: 164–170, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Murahashi K, Bucholtz DC, Nagatani S, Tsukahara S, Tsukamura H, Foster DL, Maeda KI. Suppression of luteinizing hormone pulses by restriction of glucose availability is mediated by sensors in the brain stem. Endocrinology 137: 1171–1176, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nagatani S, Bucholtz DC, Murahashi K, Estacio MA, Tsukamura H, Foster DL, Maeda KI. Reduction of glucose availability suppresses pulsatile luteinizing hormone release in female and male rats. Endocrinology 137: 1166–1170, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nagatani S, Guthikonda P, Thompson RC, Tsukamura H, Maeda KI, Foster DL. Evidence for GnRH regulation by leptin: leptin administration prevents reduced pulsatile LH secretion during fasting. Neuroendocrinology 67: 370–376, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Paxinos G, Franklin K. The Mouse Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. San Diego, CA: Academic, 2001.

- 54.Plum L, Ma X, Hampel B, Balthasar N, Coppari R, Munzberg H, Shanabrough M, Burdakov D, Rother E, Janoschek R, Alber J, Belgardt BF, Koch L, Seibler J, Schwenk F, Fekete C, Suzuki A, Mak TW, Krone W, Horvath TL, Ashcroft FM, Bruning JC. Enhanced PIP3 signaling in POMC neurons causes KATP channel activation and leads to diet-sensitive obesity. J Clin Invest 116: 1886–1901, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pocai A, Lam TK, Gutierrez-Juarez R, Obici S, Schwartz GJ, Bryan J, Aguilar-Bryan L, Rossetti L. Hypothalamic KATP channels control hepatic glucose production. Nature 434: 1026–1031, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ritter S, Dinh TT, Li AJ. Hindbrain catecholamine neurons control multiple glucoregulatory responses. Physiol Behav 89: 490–500, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schneider JE Energy balance and reproduction. Physiol Behav 81: 289–317, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schneider JE, Goldman MD, Tang S, Bean B, Ji H, Friedman MI. Leptin indirectly affects estrous cycles by increasing metabolic fuel oxidation. Horm Behav 33: 217–228, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schneider JE, Wade GN. Availability of metabolic fuels controls estrous cyclicity of Syrian hamsters. Science 244: 1326–1328, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schneider JE, Zhou D. Interactive effects of central leptin and peripheral fuel oxidation on estrous cyclicity. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 277: R1020–R1024, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Seghers V, Nakazaki M, DeMayo F, Aguilar-Bryan L, Bryan J. Sur1 knockout mice. A model for KATP channel-independent regulation of insulin secretion. J Biol Chem 275: 9270–9277, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Seino S ATP-sensitive potassium channels: a model of heteromultimeric potassium channel/receptor assemblies. Annu Rev Physiol 61: 337–362, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Shahab M, Sajapitak S, Tsukamura H, Kinoshita M, Matsuyama S, Ohkura S, Yamada S, Uenoyama Y, I'Anson H, Maeda K. Acute lipoprivation suppresses pulsatile luteinizing hormone secretion without affecting food intake in female rats. J Reprod Dev 52: 763–772, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shi NQ, Ye B, Makielski JC. Function and distribution of the SUR isoforms and splice variants. J Mol Cell Cardiol 39: 51–60, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Shiota C, Larsson O, Shelton KD, Shiota M, Efanov AM, Hoy M, Lindner J, Kooptiwut S, Juntti-Berggren L, Gromada J, Berggren PO, Magnuson MA. Sulfonylurea receptor type 1 knock-out mice have intact feeding-stimulated insulin secretion despite marked impairment in their response to glucose. J Biol Chem 277: 37176–37183, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Spanswick D, Smith MA, Groppi VE, Logan SD, Ashford ML. Leptin inhibits hypothalamic neurons by activation of ATP-sensitive potassium channels. Nature 390: 521–525, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Spanswick D, Smith MA, Mirshamsi S, Routh VH, Ashford ML. Insulin activates ATP-sensitive K+ channels in hypothalamic neurons of lean, but not obese rats. Nat Neurosci 3: 757–758, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sullivan SD, Howard LC, Clayton AH, Moenter SM. Serotonergic activation rescues reproductive function in fasted mice: does serotonin mediate the metabolic effects of leptin on reproduction? Biol Reprod 66: 1702–1706, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Szymanski LA, Schneider JE, Friedman MI, Ji H, Kurose Y, Blache D, Rao A, Dunshea FR, Clarke IJ. Changes in insulin, glucose and ketone bodies, but not leptin or body fat content precede restoration of luteinising hormone secretion in ewes. J Neuroendocrinol 19: 449–460, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tanaka T, Nagatani S, Bucholtz DC, Ohkura S, Tsukamura H, Maeda K, Foster DL. Central action of insulin regulates pulsatile luteinizing hormone secretion in the diabetic sheep model. Biol Reprod 62: 1256–1261, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Turi GF, Liposits Z, Moenter SM, Fekete C, Hrabovszky E. Origin of neuropeptide Y-containing afferents to gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons in male mice. Endocrinology 144: 4967–4974, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.van den Top M, Lyons DJ, Lee K, Coderre E, Renaud LP, Spanswick D. Pharmacological and molecular characterization of ATP-sensitive K+ conductances in CART and NPY/AgRP expressing neurons of the hypothalamic arcuate nucleus. Neuroscience 144: 815–824, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wade GN, Jones JE. Neuroendocrinology of nutritional infertility. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 287: R1277–R1296, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Xu AW, Kaelin CB, Takeda K, Akira S, Schwartz MW, Barsh GS. PI3K integrates the action of insulin and leptin on hypothalamic neurons. J Clin Invest 115: 951–958, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Xu M, Urban JH, Hill JW, Levine JE. Regulation of hypothalamic neuropeptide Y Y1 receptor gene expression during the estrous cycle: role of progesterone receptors. Endocrinology 141: 3319–3327, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Yamada K, Inagaki N. Neuroprotection by KATP channels. J Mol Cell Cardiol 38: 945–949, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Yamada K, Ji JJ, Yuan H, Miki T, Sato S, Horimoto N, Shimizu T, Seino S, Inagaki N. Protective role of ATP-sensitive potassium channels in hypoxia-induced generalized seizure. Science 292: 1543–1546, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Yang XJ, Mastaitis J, Mizuno T, Mobbs CV. Glucokinase regulates reproductive function, glucocorticoid secretion, food intake, and hypothalamic gene expression. Endocrinology 148: 1928–1932, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zhang C, Bosch MA, Levine JE, Ronnekleiv OK, Kelly MJ. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons express KATP channels that are regulated by estrogen and responsive to glucose and metabolic inhibition. J Neurosci 27: 10153–10164, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zhang S, Blache D, Blackberry MA, Martin GB. Body reserves affect the reproductive endocrine responses to an acute change in nutrition in mature male sheep. Anim Reprod Sci 88: 257–269, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]