Abstract

The majority of mammalian cells demonstrate regulatory volume decrease (RVD) following swelling caused by hyposmotic exposure. A critical signal initiating RVD is activation of nucleotide receptors by ATP. Elevated extracellular ATP in response to cytotoxic cell swelling during pathological conditions also may initiate loss of taurine and other intracellular osmolytes via anion channels. This study characterizes neuronal ATP-activated anion current and explores its role in net loss of amino acid osmolytes. To isolate anion currents, we used CsCl as the major electrolyte in patch electrode and bath solutions and blocked residual cation currents with NiCl2 and tetraethylammonium. Anion currents were activated by extracellular ATP with a Km of 70 μM and increased over fourfold during several minutes of ATP exposure, reaching a maximum after 9.0 min (SD 4.2). The currents were blocked by inhibitors of nucleotide receptors and volume-regulated anion channels (VRAC). Currents showed outward rectification and inactivation at highly depolarizing membrane potentials, characteristics of swelling-activated anion currents. P2X agonists failed to activate the anion current, and an inhibitor of P2X receptors did not block the effect of ATP. Furthermore, current activation was observed with extracellular ADP and 2-(methylthio)adenosine 5′-diphosphate, a P2Y1 receptor-specific agonist. Much less current activation was observed with extracellular UTP, suggesting the response is mediated predominantly by P2Y1 receptors. ATP caused a dose-dependent loss of taurine and alanine that could be blocked by inhibitors of VRAC. ATP did not inhibit the taurine uptake transporter. Thus extracellular ATP triggers a loss of intracellular organic osmolytes via activation of anion channels. This mechanism may facilitate neuronal volume homeostasis during cytotoxic edema.

Keywords: amino acids, taurine, cell volume

extracellular purine and pyrimidine compounds mediate a variety of brain functions by receptor-mediated action. Extracellular ATP and its metabolic products can initiate cellular responses through two types of receptors: P1 receptors, which are highly sensitive to adenosine, and P2 receptors, sensitive to adenine nucleotides. The P2 receptors are further divided into P2X (ligand-gated channels) or P2Y (G protein-coupled receptors) (1, 65, 66, 77). These receptors are widely distributed in the central nervous system and provoke a variety of effects on neurons and on glial cells.

Both P2X and P2Y receptors are expressed on neurons and astrocytes. Activation of these receptors initially can cause an increase of intracellular Ca2+ and can lead to an altered cycle of cell proliferation or to apoptosis (15, 24, 41). In neurons, P2X receptors mediate fast synaptic responses to ATP, whereas P2Y receptors cause slow changes of the membrane potential (13, 35, 39, 52, 78). Extracellular ATP applied to hippocampal neurons can inhibit synaptic transmission, activate ion channels, or potentiate the phosphorylation of membrane proteins (4, 36, 55, 63, 79). In addition to these changes occurring within short time periods, long-term tropic effects in response to ATP include neuronal maturation, neurite outgrowth (34, 87), and the expression of transmitter receptors at target cells (14).

Volume regulation in many cells occurs in response to changes in the extracellular or intracellular environment triggered by physiological or pathological cell swelling or shrinkage (67). The increased intracellular water content that occurs during cell swelling is restored to normal via loss of ions and organic osmolytes in a process called regulatory volume decrease (RVD). Chloride channels play a very important role in regulating the intracellular content of Cl−, and loss of intracellular amino acids via anion channels has been shown to contribute to RVD of many cell types (19, 37, 64).

Numerous studies have implicated extracellular ATP as an initiating signal for cellular volume regulation (12, 19, 23, 27, 31, 49, 80). In several cell types, extracellular ATP activates a current with electrophysiological characteristics similar to anion currents stimulated by cell swelling (ICl,swell) (19, 23). In other cells, extracellular ATP potentiates volume-regulated anion channels (VRAC) and amino acid efflux but cannot initiate these responses (29, 57, 90). Our previous studies demonstrated that cultured hippocampal neurons express an anion current that can be activated by extracellular ATP in the absence of osmotic swelling (47). Since ATP can be released by many cell types during insults that cause cell swelling, such as physical injury, tissue pH changes, trauma, or ischemia (10, 40, 54, 76, 81), increases in extracellular ATP may mediate volume regulation in cells of the pathologically swollen brain via anion channel activation. The ATP-activated current in hippocampal neurons also can be carried by the anionic form of the intracellular osmolyte, taurine (47). Therefore, this mechanism may directly participate in net loss of intracellular osmolytes responsible for volume regulation. In these studies, we have characterized the time course of current activation and the pharmacological kinetics of the response to ATP and established the subtype of nucleotide receptor that leads to activation of the anion current. We also have demonstrated that increased extracellular ATP acting via anion channels alters the net neuronal contents of taurine and other amino acid osmolytes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

Media components and balanced salt solutions for cell cultures were obtained from Invitrogen (Grand Island, NY). Niflumic acid was purchased from ICN Biomedicals (Aurora, OH). 4-[(2-Butyl-6,7-dichloro-2-cyclopentyl-2,3-dihydro-1-oxo-1H-inden-5-yl) oxy]butanoic acid (DCPIB) and 2′-deoxy-N6-methyladenosine 3′,5′-bisphosphate tetrasodium salt (MRS2179) were obtained from Tocris Bioscience (Ellisville, MO). All other chemicals, including ATP, ADP, UTP, suramin, reactive blue, brilliant blue G, 5-nitro-2-(3-phenylpropylamino)benzoic acid (NPPB), 2-(methylthio)adenosine 5′-diphosphate (2-MeS-ADP), pyridoxal-phosphate-6-azophenyl-2′,4′-disulfonate (PPADS), 2′-3′-O-(4-benzoylbenzoyl) ATP (Bz-ATP), α,β-methylene ATP, and β,γ-methylene ATP were of the highest grade available and were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) or Fisher Scientific (Hanover Park, IL).

Neuron cultures.

The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Wright State University approved all procedures involving animals. Hippocampal neurons were obtained from rat fetuses on the 18th day of gestation using a method modified from that originally described by Banker and Cowan (5) as previously described (47). Cells were plated at a density of 30,000 cells/cm2 in 35-mm plastic petri dishes. Some dishes contained 12-mm glass coverslips to permit transfer of the cells to the electrophysiological recording station. All growth surfaces were coated with polyornithine before the cells were plated. At the initial plating, the medium consisted of Eagle's minimum essential medium containing 50 U/ml penicillin, 50 μg/ml streptomycin, and 10% horse serum. After 4–6 h, this was replaced with growth medium consisting of Neurobasal A plus B27 additives and the same antibiotics (11). Cultures were maintained at 37°C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2. Every 3–4 days, one-half of the medium was removed and replaced with fresh growth medium. Cells were used for experiments after 10–20 days in culture.

Electrophysiology.

Whole cell recordings were made from neurons maintained at 35 ± 0.5°C and perfused at a rate that exchanges the 0.5-ml reservoir volume in 45 s. Solutions used for electrodes and perfusion solutions are described in Table 1. Electrodes pulled from borosilicate glass had resistances of 3–6 MΩ when filled with CsCl electrode solution and measured in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS).

Table 1.

Composition of perfusion and patch electrode solutions

|

Perfusion Solutions |

Patch Electrode Solutions

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PBS | CsCl | NMDG-Cl | Cs-gluconate | CsCl | NMDG-Cl | |

| NaCl | 137 | |||||

| CsCl | 100 | 100 | ||||

| NMDG | 100 | 100 | ||||

| Gluconic acid | 100 | |||||

| MgCl2 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| CaCl2 | 1.0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| KH2PO4 | 0.5 | |||||

| Na2HPO4 | 2.7 | |||||

| Glucose | 5.5 | 5.5 | 5.5 | 5.5 | 5.5 | 5.5 |

| EGTA | 10 | 10 | ||||

| ATP | 3.0 | 3.0 | ||||

| KCl | 2.7 | |||||

| Sucrose | 90 | 90 | 90 | 90 | 90 | |

| HEPES | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | |

| pH | 7.3 | 7.3 | 7.3 | 7.3 | 7.2 | 7.2 |

| Adjusted with | NaOH | CsOH | HCl | CsOH | CsOH | HCl |

| Osmolality, mosmol/kg H2O | 290 | 290 | 290 | 290 | 290 | 290 |

| Adjusted with | NaCl | Sucrose | Sucrose | Sucrose | Sucrose | Sucrose |

All concentrations are given in mM. NMDG, N-methyl-d-glucamine.

Recordings were initiated with a patch electrode containing CsCl or N-methyl-d-glucamine-Cl (NMDG-Cl) while cells were perfused with PBS. Neurons were held at −70 mV in voltage-clamp mode. After a stable recording was established, the perfusion solution was changed to CsCl, NMDG-Cl, or Cs-gluconate solution, and the holding potential was raised to 0 mV. Hippocampal neuron membrane currents then were measured every 30 s by delivering a train of 90-ms voltage steps to values ranging from −120 to +120 mV in 20-mV increments. Current-voltage (I-V) relationships for each recorded cell were determined from the average of the cell current during the last 20 ms of each voltage step. Membrane conductance for each cell was calculated by linear regression of these data between −80 and −20 mV. In some experiments, extracellular CsCl, NMDG-Cl, or Cs-gluconate was replaced with equiosmotic sucrose, and resulting shifts in membrane potential were determined.

Amino acid content and taurine uptake.

The cellular contents of amino acids and the unidirectional rate of taurine accumulation were determined using cells grown in 35-mm culture dishes as previously described (68, 71). Growth medium was rinsed from the cultures, and the cells were incubated for 30 min in PBS (Table 1). The PBS was then changed to an identical solution, except it also contained 0–100 μM ATP. For uptake studies, this solution also contained 1 μM tritiated taurine with a specific activity of 0.5 μCi/ml.

To measure amino acid contents, cultures were incubated for 30 min. The extracellular fluid was then removed from the culture dish and replaced with 1 ml of 0.6 M HClO4. Cells were scraped from the dish in this solution and centrifuged at 10,000 g for 1 min. Amino acids were measured in the supernatant by HPLC after derivatization with o-phthalaldehyde. Cellular material adherent on the culture dish was removed with 1 ml of 1.0 M NaOH, and this solution was used to dissolve the pellet from the centrifugation. Protein was determined in the resulting solution by using the method of Lowry et al. (50).

To measure taurine accumulation, a sample of PBS was removed for liquid scintillation counting after 20 min of incubation, and the cells were fixed in 1 ml of 0.6 M HClO4. The cells were scraped from the dish, and the resulting suspension was sonicated and then centrifuged. Radioactivity was determined in the supernatant. The pellet plus residual cellular material remaining on the dish were dissolved in NaOH for protein determination as described above.

Data analysis.

Results are means (SD). Curve fits were performed by linear or nonlinear regression algorithms, and SE are provided for the calculated parameters. The time course of conductance changes was analyzed by repeated-measures ANOVA with post hoc Dunnett's test. Responses to drug exposures or ion substitutions were evaluated using ANOVA followed by Dunnett's test or Student's t-test for paired or independent samples, as appropriate. Significant differences were indicated by P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Isolation of anion currents.

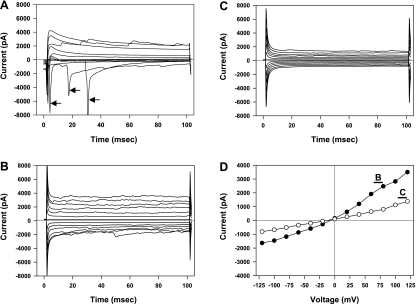

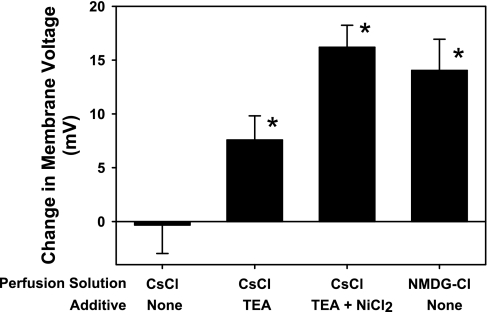

Following successful establishment of a whole cell patch recording using the CsCl patch electrode solution, depolarizing voltage steps to −50 mV or greater resulted in transient inward currents characteristic of action currents (Fig. 1A). Cells also typically demonstrated spontaneous transient currents resembling synaptic currents. To ensure that our recordings were from viable neurons, we abandoned recordings from cells that did not demonstrate the action currents in response to depolarizing command voltages. After the perfusing PBS was replaced with 100 mM CsCl perfusion solution, the resting potential was −4.9 (SD 3.4) mV. Once this solution change was complete, the holding potential was moved to 0 mV. Action currents were eliminated during all voltage steps in this configuration, but the current magnitude in response to both depolarizing and hyperpolarizing voltage commands was increased compared with cells perfused with PBS (Fig. 1B). Therefore, ion substitution experiments were performed to determine which ions were responsible for the basal membrane currents. In this analysis, junction potentials created at the AgCl reference electrode were numerically compensated using the algorithm provided with pClamp 8.2 (Axon Instruments, Sunnyvale, CA). Reducing extracellular CsCl to 50 mM by equiosmotic replacement with sucrose produced little change in membrane potential (Fig. 2), suggesting that the membrane was equally permeable to Cs+ and Cl− under these conditions. However, further reductions of the extracellular CsCl concentration to 25 or 10 mM resulted in positive membrane potential shifts of +18.7 (SD 4.9) or +39.7 (SD 6.9) mV, respectively. These values are still below those predicted for a membrane solely permeable to Cl− and over this wide range of CsCl concentrations predict a relative permeability (PCl/PCs) of 4.3 (SE 1.0) using the Goldman-Katz model for two permeable ions. To test whether Cs+ permeability is responsible for the variance from the predicted membrane potential shift for a single permeant anion, we performed experiments with 100 mM NMDG rather than Cs+ in extracellular and patch electrode solutions. Under these conditions, reducing extracellular NMDG-Cl from 100 to 50 or 25 mM (with equiosmotic sucrose replacement) resulted in membrane potential shifts of +14.0 (SD 6.2) or +30.6 (SD 7.5) mV, respectively (Fig. 2). Over this range of extracellular NMDG-Cl concentrations, we calculated a relative permeability PCl/PNMDG of 12.7 (SE 4.9). In other studies, the membrane potential hyperpolarized when the perfusing solution was changed from 100 mM Cs-gluconate to 50 mM Cs-gluconate (with equiosmotic sucrose replacement). Thus we conclude that cultured hippocampal neurons have a significant permeability to Cs+ under our basal recording conditions.

Fig. 1.

Patch-clamp recordings of hippocampal neurons. Recordings were obtained from a single cell using an electrode solution containing 100 mM CsCl and depict representative results from all cells used in these studies. A: voltage-clamp recordings made within several minutes of establishing a whole cell recording while the cell is perfused with PBS. The capacitive current was electronically eliminated in this recording. The membrane potential was held at −70 mV and stepped between −90 and +90 mV in 20-mV steps. Rapidly inactivating inward currents appeared with voltage steps to −50 mV and higher (arrows). B: membrane currents recorded from the same cell after the perfusate was replaced with 100 mM CsCl solution and the holding potential changed to 0 mV. Capacitive current compensation was not used for this and subsequent recordings. The membrane voltage was stepped between −120 and +120 mV in 20-mV steps. C: membrane currents recorded using the same holding potential and voltage steps following the introduction of 1 mM tetraethylammonium (TEA) plus 100 μM NiCl2 to the CsCl perfusing solution. D: current-voltage relationships measured from data shown in B (•) and C (○) as indicated. The current for each voltage step was calculated as the average of the last 20 ms of the appropriate tracing.

Fig. 2.

Change in membrane potential recorded from hippocampal neurons following substitution of extracellular ions. Cells were recorded in current-clamp mode while 50% of the major extracellular cationic and anionic electrolytes present in the perfusing solution were replaced with sucrose. Some perfusing solutions contained additives as indicated. TEA was used at a concentration of 1 mM; NiCl2 was used at a concentration of 100 μM. NMDG, N-methyl-d-glucamine. Each bar is the mean ± SE obtained from 7–11 different cells. *P < 0.05, significantly different from zero.

We evaluated various ion channel inhibitors for their ability to reduce the cation permeability of the neurons during perfusion with 100 mM CsCl. With 1 mM tetraethylammonium (TEA) added to the perfusion solution, cells showed a depolarizing membrane potential change when extracellular CsCl was reduced to 50 mM (Fig. 2). Little additive effect was observed when 100 μM BaCl and 1 mM TEA were combined (data not shown). However, with 1 mM TEA plus 100 μM NiCl2 (TN) added to the extracellular solution, a reduction in extracellular CsCl concentration to 50 mM resulted in a membrane potential shift of +16.2 (SD 5.4) mV. This compares favorably with the value of +18.6 mV calculated using the Nernst equation at 35°C and yields a PCl/PCs relative permeability of 8.8 (SE 2.9). The addition of TN also reduced the membrane conductance of cells perfused with 100 mM CsCl by 45% (SD 32%) (Fig. 1D). Thus, in the presence of these cation channel inhibitors, ∼90% of the resting membrane conductance is due to current carried by chloride ions. The remaining electrophysiological studies described were performed with TN in all CsCl perfusing solutions.

ATP-activated anion currents.

Hippocampal neurons with 100 mM CsCl in the patch electrode and 100 mM CsCl plus TN in the perfusion solution had an input resistance of 274 (SD 74) MΩ and a membrane capacitance of 50.4 (SD 19) pF. The I-V curve was slightly outward rectifying with a conductance of 88.8 (SD 37.0) pS/pF measured between −80 and −20 mV (Fig. 3, A and C). Adding 10–100 μM ATP to the perfusion solution increased the membrane conductance within several minutes, reaching a peak value between 5 and 20 min after the start of ATP exposure (Fig. 3D). With 100 μM ATP, the average maximum membrane conductance relative to that measured before ATP exposure (Relative Conductance) was 2.86 (SD 3.3) and appeared 9.00 (SD 4.17) min after the start of exposure (Fig. 3D). This change in membrane conductance was completely inhibited with 100 μM of either of the anion channel inhibitors NPPB or niflumic acid (Fig. 3E). The dose-response curve for the ATP-activated chloride conductance can be modeled as a Michaelis-Menten relationship with a maximal relative conductance of 3.8 and an ATP concentration at half-maximal activation of ∼70 μM (Fig. 3F). The calculated intercept of this curve at 0 μM ATP is not statistically different from unity.

Fig. 3.

Characteristics of the ATP-activated anion current in hippocampal neurons. A: membrane currents of a hippocampal neuron in voltage-clamp mode recorded with 100 mM CsCl in electrode and perfusion solutions. The perfusion solution also contained TEA and NiCl2 to inhibit cation currents as described in the text. B: membrane currents from the same cell as in A after a 7-min exposure to 100 μM ATP. A substantial increase in membrane conductance is evident compared with the currents shown in A. C: voltage-current relationships from data shown in A (•) and B (○). D: time dependence of the ATP-activated anion conductance. At time 0, 100 μM ATP was added to the perfusion solution. Data are expressed as the relative conductance, defined as the value measured at each time point divided by the conductance measured just before the start of ATP exposure. Each point represents the mean ± SE of data from 13 cells. E: inhibition of ATP-activated conductance by anion channel blockers. Values are the maximal relative conductance measured within 15 min of the start of ATP exposure. Cells were exposed to 100 μM ATP in the absence or presence of one of the channel blockers, 5-nitro-2-(3-phenylpropylamino)benzoic acid (NPPB) or niflumic acid (100 μM). Bars represent means ± SE of 5–11 cells. F: dose response of the ATP-activated anion conductance. Values are the maximal relative conductance measured within 15 min of the start of ATP exposure. Symbols represent means ± SE of data from 6–22 cells exposed to each ATP concentration. The smooth curve is the best fit of the data to a Michaelis-Menten relation. *P < 0.05, significantly different from unity.

ATP activates anion currents via P2Y1 receptors.

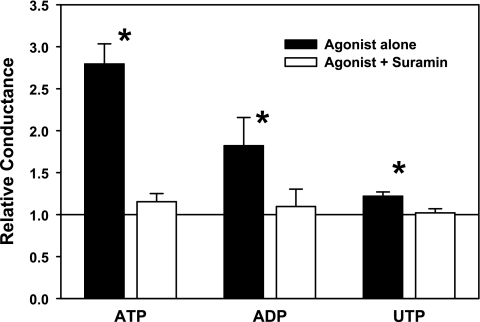

The nucleotides ATP, ADP, and UTP activated hippocampal neuron chloride conductance (Fig. 4). At equal concentrations of 100 μM, the rank order of the magnitude of the conductance response was ATP > ADP > UTP. For each agonist, the general P2 receptor antagonist suramin (100 μM) completely blocked the conductance increase. The P2Y receptor antagonists reactive blue and PPADS also completely blocked the activation of neuronal chloride conductance when added with 100 μM ATP (Table 2). Indeed, reactive blue significantly decreased neuronal conductance to <75% of control values even in the presence of 100 μM ATP, whereas in the absence of exogenous ATP, 100 μM suramin and reactive blue inhibited the baseline conductance after 6 min of exposure by 25.4% (SD 12.6%) and 16.9% (SD 15.3%), respectively. In contrast, the P2X antagonist brilliant blue G had no effect on the conductance increase caused by exposure to 30 μM ATP. In addition, neither the P1 agonist adenosine nor any of the P2X agonists (α,β-methylene ATP, β,γ-methylene ATP, or Bz-ATP) caused a change in neuronal chloride conductance.

Fig. 4.

Purinergic sensitivity of the ATP-activated anion conductance in hippocampal neurons. Values are the maximal relative conductance measured within 15 min of the start of ATP exposure. Nucleotides were used at 100 μM concentrations. For some cells, 100 μM of the purinergic receptor antagonist suramin was added to the perfusion solution 5 min before and throughout exposure to the nucleotide agonist. Bars represent means ± SE of data from 5–11 cells in each group. *P < 0.05, significantly different from unity.

Table 2.

Effects of purinergic receptor agonists and antagonists on hippocampal neuron chloride conductance

| Drug | Relative Conductance after 6-Min Exposure |

|---|---|

| Control | |

| 30 μM ATP | 1.97 (0.70) |

| 100 μM ATP | 2.49 (1.8) |

| P2Y antagonists (plus 100 μM ATP) | |

| Reactive blue | 0.73 (0.07)* |

| PPADS | 1.18 (0.42)* |

| P2X antagonist (plus 30 μM ATP) | |

| Brilliant blue G | 2.67 (1.37) |

| P2X agonists | |

| α,β-Methylene ATP | 0.92 (0.12)* |

| β.γ-Methylene ATP | 1.06 (0.26)* |

| Bz-ATP | 0.98 (0.12)* |

| P1 agonist | |

| Adenosine | 1.08 (0.30)* |

Values are means (SD) for 4–18 independent measurements. All drugs were used at a concentration of 100 μM. PPADS, pyridoxal-phosphate-6-azophenyl-2′,4′-disulfonate.

P < 0.05, significantly different from the value obtained during control drug exposure.

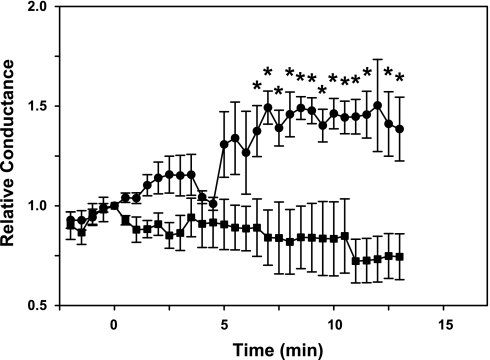

To further define the contribution of P2Y receptor subtypes to the neuronal anion conductance, we utilized the P2Y1 selective receptor agonist 2-MeS-ADP and the P2Y1 receptor antagonist MRS2179 (Fig. 5). 2-MeS-ADP increased chloride conductance with a time course similar to that observed with ATP, although the maximal conductance increase was nominally less than that obtained with 100 μM ATP. MRS2179 blocked the conductance increase normally observed with 100 μM ATP. The small decrease in conductance obtained with MRS2179 treatment in the presence of ATP was not statistically significant.

Fig. 5.

Sensitivity of the neuronal anion conductance to P2Y1 receptor subtype activation and inhibition. Values are the relative conductance measured following introduction of 100 μM 2-(methylthio)adenosine 5′-diphosphate (2-MeS-ADP; •) or 100 μm ATP plus 1 μM MRS2179 (▪) to the perfusing solution at time 0. Each data point is the mean ± SE of 5–7 independent measurements. *P < 0.05, significantly different from unity.

Amino acid loss during ATP exposure.

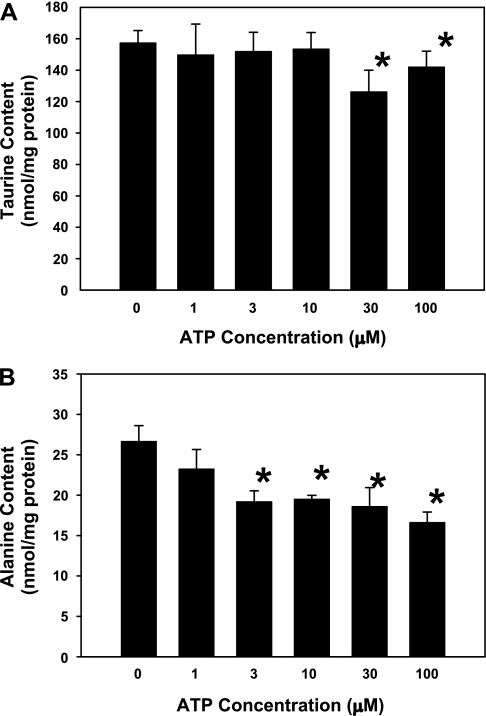

Because of the role of anion channels play in amino acid release during cell swelling, the importance of taurine as an intracellular osmolyte involved in cell volume regulation, and the mechanism of extracellular ATP-induced volume regulation described for other cell types (19, 23, 59, 75), we examined whether treatment of the cultured neurons with 100 μM ATP would decrease neuronal contents of taurine and other amino acids. The standard defined growth medium used for these neuronal cultures does not contain taurine. Therefore, for these experiments, cells were grown in medium supplemented with 100 μM taurine for 3 days before experimentation. This treatment increased neuronal taurine contents from 19 (SD 4) nmol/mg protein measured in the absence of taurine supplementation to 144 (SD 31) nmol/mg protein with taurine added to the growth medium, a value approximately twice that of the hippocampus in situ (72). During a 30-min exposure to PBS containing 0–10 μM ATP, no change in neuronal taurine contents was observed (Fig. 6A). However, neuronal taurine contents decreased significantly following a 30-min exposure to either 30 or 100 μM ATP. Alanine contents also decreased in a dose-dependent manner from 26.6 (SD 6.2) nmol/mg protein in 0 μM ATP to 16.6 (SD 3.2) nmol/mg protein in 100 μM ATP (Fig. 6B). Neuronal contents of aspartate, glutamate, glutamine, glycine, and γ-aminobutyric acid were not affected by ATP treatment.

Fig. 6.

Amino acid contents of hippocampal neurons after exposure to extracellular ATP. Taurine (A) and alanine contents (B) were measured after 30 min of exposure to various ATP concentrations in PBS. Bars represent means ± SE of data from 6–15 cultures. *P < 0.05, significantly different from the content measured in 0 μM ATP.

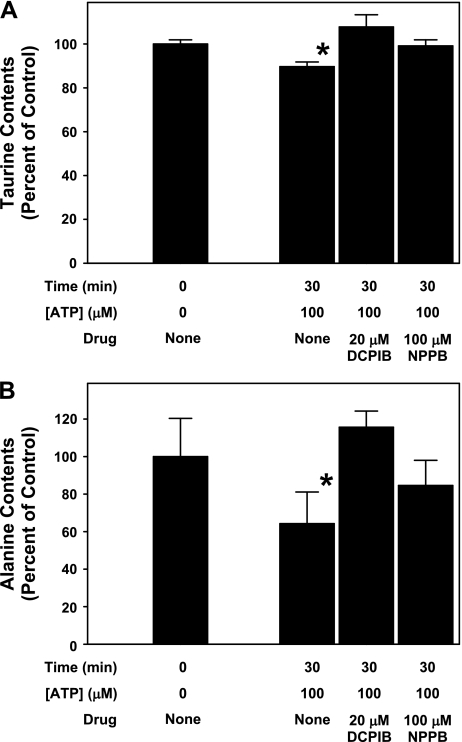

To examine whether the ATP-induced losses of taurine and alanine were due to movement through VRAC, these experiments were repeated with cells exposed to 100 μM ATP in the presence of the VRAC inhibitors DCPIB or NPPB (Fig. 7). Similar to results shown in Fig. 6, 30-min exposure to 100 μM ATP caused an ∼10 and 40% decrease in neuronal taurine and alanine contents, respectively. These decreases were completely inhibited with either 20 μM DCPIB or 100 μM NPPB added during ATP exposure.

Fig. 7.

Anion channel inhibitors block net loss of neuronal taurine and alanine contents during exposure to ATP. Taurine (A) and alanine contents (B) are expressed as a percentage of the value measured in control cells before ATP and drug exposure. ATP alone resulted in a significant decrease in the net content of each amino acid. Both 20 μM DCPIB and 100 μM NPPB completely blocked this net amino acid loss. Values are means ± SE of results from triplicate experiments from different sets of cultures. *P < 0.05, significantly different from the content measured before ATP and drug treatment.

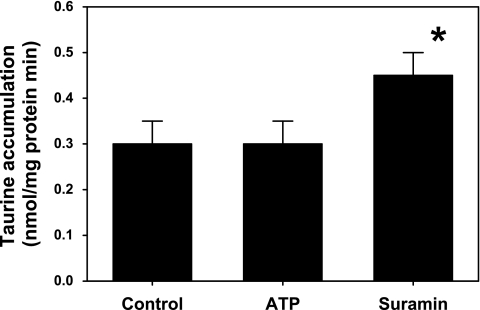

Net loss of intracellular taurine observed during ATP exposure might result from inhibition of active taurine reaccumulation following passive loss through membrane channels. Therefore, we measured unidirectional taurine accumulation to test whether ATP exposure downregulated or inhibited the taurine transporter. We found the rate of taurine accumulation was not affected by 100 μM ATP (Fig. 8). However, taurine accumulation was significantly increased in the presence of the nonselective P2 receptor antagonist suramin (100 μM).

Fig. 8.

Taurine accumulation into hippocampal neurons. Uptake was measured as unidirectional transport of radioactive taurine. Cultures were incubated for 20 min in PBS containing 100 μM ATP, 100 μM suramin, or no additive (control). *P < 0.05, significantly different from the accumulation rate measured in control cultures.

DISCUSSION

The present study characterizes a neuronal current activated by extracellular ATP, the nucleotide receptor mediating this electrophysiological response, the effect of nucleotide receptor activation on amino acid contents, and the mechanism of ATP-induced taurine loss. We previously demonstrated the presence of an ATP-activated current in cultured hippocampal neurons (47). The pharmacological profile of the ATP response described presently indicates this current is activated by P2Y1 and not P2Y2 receptors. The ATP-induced increase in neuronal membrane conductance is observed with cesium and chloride as the primary conducting ions in the perfusing and electrode solutions and is sensitive to the anion channel blockers niflumic acid and DCPIB. Thus, we conclude, the ATP-activated current under these conditions is carried by chloride ions moving through the VRAC. Our previous data suggested the channels activated by ATP exposure can conduct taurine in its anionic form. The present results indicate ATP-induced activation of the VRAC can lead to net reduction of cellular taurine contents.

In contrast to previous studies of primary cultured rat astrocytes, hippocampal neurons demonstrate a cesium permeability comparable to that of chloride when depolarized in the presence of 100 mM CsCl in perfusion and electrode solutions. The cesium permeability is only partially inhibited by several potassium channel blockers but is completely blocked by the presence of TEA plus NiCl2 in the perfusing medium. In hippocampal neurons, NiCl2 has been shown to inhibit calcium-sensitive cation channels permeable to potassium and the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (86, 88). However, because the increased conductance we measured in hippocampal neurons is due to cesium ions and is inhibited with a Ni2+ concentration less than 1 mM, we suggest the current is mediated by a nonspecific cation channel activated by intracellular calcium ion (16, 73). A calcium-dependent cation current activated by metabotropic glutamate receptors has previously been described in CA1 hippocampal neurons held at −60 mV (16); however, we did not test the glutamate-dependence of the nonspecific current identified in our neuron cultures. Because our objective was to examine ATP-activated anion currents, once we determined the neurons were predominantly permeable to chloride in the presence of 1 mM TEA plus 100 μM Ni2+, we did not further characterize this cation current.

Extracellular ATP activated a neuronal anion current with a time course of several minutes, similar to that observed in rat astrocytes and other cell types (19, 23). This current was inhibited by niflumic acid and demonstrated inactivation at highly depolarizing membrane potentials, characteristics of ICl,swell described by others (19, 37, 47, 69, 82). Because current activation by ATP required several minutes to reach a maximum, the nucleotide receptor mediating this response is more likely to be one of the metabotropic, G protein-coupled, P1, or P2Y receptors rather than a rapidly activating ligand-gated channel such as a P2X receptor subtype. Our pharmacological results provide further evidence against a P2X-receptor or P1-receptor mediated effect of ATP on the neuronal anion conductance. The P2X antagonist brilliant blue G had no effect on the ATP-activated current, and application of the P2X-specific agonists α,β-methylene ATP, β,γ-methylene ATP, and Bz-ATP (43) did not increase neuronal anion conductance. Furthermore, adenosine did not activate the anion conductance. In contrast, each of the P2Y antagonists, suramin, reactive blue, and PPADS (77), completely blocked the ATP-activated anion conductance. Thus a role for P2X or P1 receptors in the ATP-induced activation of the anion current is not likely. Indeed, the P2Y antagonist reactive blue reduced baseline anion conductance in both the absence and presence of ATP in the perfusing solution, suggesting that P2Y receptors stimulated by endogenously released ATP may partially activate the anion conductance under basal conditions.

The hippocampus expresses a variety of P2Y receptor subtypes including P2Y1, P2Y2, P2Y4, and P2Y6 (see Ref. 13 for review). In situ hybridization also has revealed other nucleotide receptors in the principal cell layers of the mouse hippocampus (45). Freshly isolated rat hippocampal astrocytes express mRNA and immunoreactivity for P2Y1, P2Y2, and P2Y4 receptors (92), and subcellular localization of P2Y1, P2Y2 and P2Y12 receptors has been observed in cultured rat forebrain astrocytes and C6 glioma cells (42). P2Y1 receptors have been observed immunohistochemically in hippocampal pyramidal cells and interneurons of the rat and human (30, 60, 61), and functional evidence points to the presence of P2Y1, P2Y2, and P2Y4 receptors that can alter neurotransmitter release or voltage-activated potassium currents in neurons from the rat hippocampus (55, 63, 79). Since we observed only a small conductance change when UTP was applied to the cells, we conclude P2Y2, P2Y4 and P2Y6 receptors are not highly coupled to the increased anion current (2). Furthermore, our results showing activation of anion conductance by the P2Y1-specific agonist 2-MeS-ADP and inhibition of ATP-induced current activation by the P2Y1 antagonist MRS2179 suggest the majority of the ATP-activated anion current is mediated by the P2Y1 receptor subtype, a result similar to that reported for cultured rat astrocytes (19). However, since there are no specific agonists or antagonists for all of the various P2Y receptor subtypes (2), we also used the profile of agonist activities to examine which other receptor subtypes are likely to mediate the increased anion conductance in cultured hippocampal neurons. We found a somewhat greater increase in anion conductance with the application of ATP compared with that of ADP. Although this result argues against the involvement of the ADP-preferring P2Y1 receptors (2), the presence of extracellular ATPases and nucleotidases may confound this interpretation. The rate of ATP hydrolysis in hippocampal synaptosomes is twice that of ADP hydrolysis and over 10 times that of AMP hydrolysis (20). As a result, even at the high concentrations used in this study, exogenously applied ATP is rapidly converted to ADP, whereas AMP appears at a much slower rate (17). Thus, during the time course of our experiments, ectonucleotidases acting on exogenous ATP would first produce ADP, which still might activate ADP-preferring nucleotide receptors. Exogenous ADP applied to the cells would be converted to AMP, a compound that is a poor substrate for nucleotide receptors.

Because our cultures were prepared from whole hippocampi, a variety of cell types were likely to be present. With our methods, these primary cultures of rat hippocampal neurons contained ∼20% astroglial cells as defined by counts of glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP)-positive cells and the specific activity of the astrocyte-specific enzyme glutamine synthetase (71). All cells used in these studies were neurons as defined by their general morphological appearance and the presence of inward currents observed upon membrane depolarization; however, the specific neuronal cell type was not characterized. Although each cell responded to application of ATP with an increase in anion conductance, significant variability was observed in the magnitude and the time course of the current activation. This variability in the ATP response may be due to the variety of neuronal subtypes present, including GABAergic and glycinergic interneurons as well as pyramidal neurons (3, 8, 18). At least some hippocampal interneurons express P2Y1 receptors (61); however, the expression and cell surface density of nucleotide receptor may be variable within each neuronal subtype (25).

Nucleotide receptors have been shown to play an important role in hyposmotic volume regulation of rat hepatoma cells, human hepatocytes, Necturus erythrocytes, and rat astrocytes (19, 23, 38, 48, 49, 80). Additional studies have demonstrated ATP-induced activation of anion channels in both osmotically swollen and normal cells (26, 51, 53, 56, 83, 89). In other cells, extracellular ATP does not initiate an anion current but can potentiate such currents activated by hyposmotic swelling (29, 90). We previously demonstrated a similar potentiation of the ATP-activated anion current by hyposmotic exposure in these cultured hippocampal neurons (47). Since we observed that inhibitors of nucleotide receptors reduce anion currents in isosmotic conditions, we suggest current can be activated by basal levels of extracellular ATP present in these cultures incubated in isosmotic conditions.

The present studies indicate P2Y1 receptors are coupled to the activation of anion currents and amino acid loss in hippocampal neurons. In rat astrocytes, P2Y1 receptors mediate the swelling-induced increase in anion conductance (19), whereas P2Y2 receptors activate anion conductances in cell lines of kidney distal tubule and tracheal epithelial cells (9, 89). In several of these cellular systems, one functional effect of nucleotide receptor-activated anion conductance is net efflux of intracellular osmolytes and reduction in cellular volume. For rat astrocyte cultures, ATP acts through P2Y receptors to increase the efflux of amino acids via anion channels during hyposmotic swelling (57). ATP-induced amino acid efflux from astrocyte cultures also has been reported to occur by activation of P2X receptors (22).

We have previously established that osmotic swelling and activation of nucleotide receptors in hippocampal neurons increase the membrane conductance to taurine (47), a major intracellular osmolyte of the brain (62, 74, 91). The present study demonstrates that exposure of hippocampal neurons to ATP also leads to a dose-dependent reduction in net amino acid contents. Reduction of the ATP-stimulated amino acid efflux by pharmacological inhibitors of the VRAC supports the concept that neuronal volume regulation in isosmotic conditions is mediated via osmolyte-conducting channels that are activated by extracellular nucleotide receptors. Efflux of amino acids such as glutamate, glutamine, and aspartate as well as potentially other organic osmolytes may be increased when anion channels are activated by cell swelling or exposure to ATP (37, 59, 82). However, in these cultured neurons, taurine and alanine were the only amino acids that showed net loss during ATP exposure. This selectivity in amino acid loss may be due to one of several factors. First, permeability through volume-activated anion channels relative to that of chloride varies for different amino acid species (82). Thus the difference in the percent loss of taurine compared with alanine may represent differences in the permeability of these amino acids through the VRAC. For taurine, the relative permeability is ∼75% in MDCK cells (82) and 20% in C6 glioma cells (37). Second, the lack of change in the net content of amino acids other than taurine and alanine may be a result of rapid reuptake into adjacent glial cells or into the neurons from which they were released. Although taurine also is known to be accumulated by neurons and glial cells (6, 32, 33, 71), we found that ATP did not alter unidirectional uptake of taurine into the neuron cultures. Conversely, the broadly acting P2 receptor antagonist suramin increased the rate of taurine accumulation. Although this drug has been shown to directly inhibit volume-activated anion currents in cultured endothelial cells (21), unidirectional accumulation of the extracellular radioactive tracer measured in these studies would not be altered by changes in efflux pathways. Indeed, inhibition of passive taurine-conducting channels would be expected to decrease rather than increase the unidirectional movement of [3H]taurine into the cells. These data also imply that the net taurine loss observed in the presence of ATP is not a result of inhibition of the taurine accumulation pathway. Finally, amino acids such as glutamate, glutamine, and aspartate are metabolically coupled to the Krebs cycle intermediates and thus may be replaced via various transaminase reactions if intracellular contents are lost via increased efflux. Since taurine is synthesized relatively slowly in brain cells compared with other amino acids (7), replacement of lost taurine by anabolic reactions is not possible during the period of our studies.

ATP is released into the extracellular space during conditions associated with cell swelling such as hyposmotic exposure and ischemia (54, 76). In addition, taurine is mobilized into the extracellular space during osmotic, ischemic, and traumatic brain edema (28, 44, 84, 85). Thus our data suggest activation of a purinergic signaling pathway may initiate volume regulation in neurons via the loss of taurine and other amino acid osmolytes during these diverse pathological conditions. Differential sensitivity of neurons and astroglial cells to osmolyte loss initiated by swelling and by extracellular ATP (46, 70) may influence relative volume changes in these cell types and lead to regulation of neuronal volume in the presence of pronounced glial swelling, a characteristic of cytotoxic brain edema. Thus regulation of neuronal volume via ATP released by glial cells would represent an important neuronal-glial interaction involved in the adaptation of brain tissue to traumatic or metabolic insults that can precipitate brain edema.

GRANTS

This research was supported in part by National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke Grant NS-37485.

Acknowledgments

We thankfully acknowledge Peter Lauf and Daniel Halm for helpful and insightful review of this manuscript.

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. The article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abbracchio MP, Burnstock G. Purinoceptors: are there families of P2X and P2Y purinoceptors? Pharmacol Ther 64: 445–475, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abbracchio MP, Burnstock G, Boeynaems JM, Barnard EA, Boyer JL, Kennedy C, Knight GE, Fumagalli M, Gachet C, Jacobson KA, Weisman GA. International Union of Pharmacology LVIII: update on the P2Y G protein-coupled nucleotide receptors: from molecular mechanisms and pathophysiology to therapy. Pharmacol Rev 58: 281–341, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Antonucci DE, Lim ST, Vassanelli S, Trimmer JS. Dynamic localization and clustering of dendritic Kv2.1 voltage-dependent potassium channels in developing hippocampal neurons. Neuroscience 108: 69–81, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balachandran C, Bennett MR. ATP-activated cationic and anionic conductances in cultured rat hippocampal neurons. Neurosci Lett 204: 73–76, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Banker GA, Cowan WM. Rat hippocampal neurons in dispersed cell culture. Brain Res 126: 397–342, 1977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beetsch JW, Olson JE. Hyperosmotic exposure alters total taurine quantity and cellular transport in rat astrocyte cultures. Biochim Biophys Acta 1290: 141–148, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beetsch JW, Olson JE. Taurine synthesis and cysteine metabolism in cultured rat astrocytes: effects of hyperosmotic exposure. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 274: C866–C874, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Benson DL, Watkins FH, Steward O, Banker G. Characterization of GABAergic neurons in hippocampal cell cultures. J Neurocytol 23: 279–295, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bidet M, De Renzis G, Martial S, Rubera I, Tauc M, Poujeol P. Extracellular ATP increases [Ca2+]i in distal tubule cells. I. Evidence for a P2Y2 purinoceptor. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 279: F92–F101, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boudreault F, Grygorczyk R. Cell swelling-induced ATP release and gadolinium-sensitive channels. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 282: C219–C226, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brewer GJ, Torricelli JR, Evege EK, Price PJ. Optimized survival of hippocampal neurons in B27-supplemented Neurobasal, a new serum-free medium combination. J Neurosci Res 35: 567–576, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bryan-Sisneros A, Sabanov V, Thoroed SM, Doroshenko P. Dual role of ATP in supporting volume-regulated chloride channels in mouse fibroblasts. Biochim Biophys Acta 1468: 63–72, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burnstock G, Knight GE. Cellular distribution and functions of P2 receptor subtypes in different systems. Int Rev Cytol 240: 31–304, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Choi RC, Siow NL, Cheng AW, Ling KK, Tung EK, Simon J, Barnard EA, Tsim KW. ATP acts via P2Y1 receptors to stimulate acetylcholinesterase and acetylcholine receptor expression: transduction and transcription control. J Neurosci 23: 4445–4456, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ciccarelli R, Ballerini P, Sabatino G, Rathbone MP, D'Onofrio M, Caciagli F, Di Iorio P. Involvement of astrocytes in purine-mediated reparative processes in the brain. Int J Dev Neurosci 19: 395–414, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crepel V, Aniksztejn L, Ben-Ari Y, Hammond C. Glutamate metabotropic receptors increase a Ca2+-activated nonspecific cationic current in CA1 hippocampal neurons. J Neurophysiol 72: 1561–1569, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cunha RA Regulation of the ecto-nucleotidase pathway in rat hippocampal nerve terminals. Neurochem Res 26: 979–991, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Danglot L, Rostaing P, Triller A, Bessis A. Morphologically identified glycinergic synapses in the hippocampus. Mol Cell Neurosci 27: 394–403, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Darby M, Kuzmiski JB, Panenka W, Feighan D, MacVicar BA. ATP released from astrocytes during swelling activates chloride channels. J Neurophysiol 89: 1870–1877, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.De Paula Cognato G, Bruno AN, Vuaden FC, Sarkis JJ, Bonan CD. Ontogenetic profile of ectonucleotidase activities from brain synaptosomes of pilocarpine-treated rats. Int J Dev Neurosci 23: 703–709, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Droogmans G, Maertens C, Prenen J, Nilius B. Sulphonic acid derivatives as probes of pore properties of volume-regulated anion channels in endothelial cells. Br J Pharmacol 128: 35–40, 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Duan S, Anderson CM, Keung EC, Chen Y, Chen Y, Swanson RA. P2X7 Receptor-mediated release of excitatory amino acids from astrocytes. J Neurosci 23: 1320–1328, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Feranchak AP, Fitz JG, Roman RM. Volume-sensitive purinergic signaling in human hepatocytes. J Hepatol 33: 174–182, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fields RD, Stevens B. ATP: an extracellular signaling molecule between neurons and glia. Trends Neurosci 23: 625–633, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Filippov AK, Choi RC, Simon J, Barnard EA, Brown DA. Activation of P2Y1 nucleotide receptors induces inhibition of the M-type K+ current in rat hippocampal pyramidal neurons. J Neurosci 26: 9340–9348, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fleischhauer JC, Mitchell CH, Peterson-Yantorno K, Coca-Prados M, Civan MM. PGE2, Ca2+, and cAMP mediate ATP activation of Cl− channels in pigmented ciliary epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 281: C1614–C1623, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Galietta LJ, Falzoni S, Di Virgilio F, Romeo G, Zegarra-Moran O. Characterization of volume-sensitive taurine- and Cl−-permeable channels. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 273: C57–C66, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Haugstad TS, Langmoen IA. Release of brain amino acids during hyposmolar stress and energy deprivation. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol 8: 159–168, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hazama A, Shimizu T, Ando-Akatsuka Y, Hayashi S, Tanaka S, Maeno E, Okada Y. Swelling-induced, CFTR-independent ATP release from a human epithelial cell line: lack of correlation with volume-sensitive Cl− channels. J Gen Physiol 114: 525–533, 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Heine C, Heimrich B, Vogt J, Wegner A, Illes P, Franke H. P2 receptor-stimulation influences axonal outgrowth in the developing hippocampus in vitro. Neuroscience 138: 303–311, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hisadome K, Koyama T, Kimura C, Droogmans G, Ito Y, Oike M. Volume-regulated anion channels serve as an auto/paracrine nucleotide release pathway in aortic endothelial cells. J Gen Physiol 119: 511–520, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Holopainen I, Kontro P. High-affinity uptake of taurine and beta-alanine in primary cultures of rat astrocytes. Neurochem Res 11: 207–215, 1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hruska RE, Padjen A, Bressler R, Yamamura HI. Taurine: sodium-dependent, high-affinity transport into rat brain synaptosomes. Mol Pharmacol 14: 77–85, 1978. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huang CM, Kao LS. Nerve growth factor, epidermal growth factor, and insulin differentially potentiate ATP-induced [Ca2+]i rise and dopamine secretion in PC12 cells. J Neurochem 66: 124–130, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Illes P, Ribeiro AJ. Molecular physiology of P2 receptors in the central nervous system. Eur J Pharmacol 483: 5–17, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Inoue K The functions of ATP receptors in the hippocampus. Pharmacol Res 38: 323–331, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jackson PS, Strange K. Volume-sensitive anion channels mediate swelling-activated inositol and taurine efflux. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 265: C1489–C1500, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Junankar PR, Karjalainen A, Kirk K. The role of P2Y1 purinergic receptors and cytosolic Ca2+ in hypotonically activated osmolyte efflux from a rat hepatoma cell line. J Biol Chem 277: 40324–40334, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Khakh BS Molecular physiology of P2X receptors and ATP signalling at synapses. Nat Rev Neurosci 2: 165–174, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kimelberg HK Increased release of excitatory amino acids by the actions of ATP and peroxynitrite on volume-regulated anion channels (VRACs) in astrocytes. Neurochem Int 45: 511–519, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.King BF, Neary JT, Zhu Q, Wang S, Norenberg MD, Burnstock G. P2 purinoceptors in rat cortical astrocytes: expression, calcium-imaging and signalling studies. Neuroscience 74: 1187–1196, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Krzeminski P, Misiewicz I, Pomorski P, Kasprzycka-Guttman T, Baranska J. Mitochondrial localization of P2Y1, P2Y2 and P2Y12 receptors in rat astrocytes and glioma C6 cells. Brain Res Bull 71: 587–592, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lambrecht G Agonists and antagonists acting at P2X receptors: selectivity profiles and functional implications. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 362: 340–350, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lehmann A Effects of microdialysis-perfusion with anisoosmotic media on extracellular amino acids in the rat hippocampus and skeletal muscle. J Neurochem 53: 525–535, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lein ES, Hawrylycz MJ, Ao N, Ayres M, Bensinger A, Bernard A, Boe AF, Boguski MS, Brockway KS, Byrnes EJ, Chen L, Chen L, Chen TM, Chin MC, Chong J, Crook BE, Czaplinska A, Dang CN, Datta S, Dee NR, Desaki AL, Desta T, Diep E, Dolbeare TA, Donelan MJ, Dong HW, Dougherty JG, Duncan BJ, Ebbert AJ, Eichele G, Estin LK, Faber C, Facer BA, Fields R, Fischer SR, Fliss TP, Frensley C, Gates SN, Glattfelder KJ, Halverson KR, Hart MR, Hohmann JG, Howell MP, Jeung DP, Johnson RA, Karr PT, Kawal R, Kidney JM, Knapik RH, Kuan CL, Lake JH, Laramee AR, Larsen KD, Lau C, Lemon TA, Liang AJ, Liu Y, Luong LT, Michaels J, Morgan JJ, Morgan RJ, Mortrud MT, Mosqueda NF, Ng LL, Ng R, Orta GJ, Overly CC, Pak TH, Parry SE, Pathak SD, Pearson OC, Puchalski RB, Riley ZL, Rockett HR, Rowland SA, Royall JJ, Ruiz MJ, Sarno NR, Schaffnit K, Shapovalova NV, Sivisay T, Slaughterbeck CR, Smith SC, Smith KA, Smith BI, Sodt AJ, Stewart NN, Stumpf KR, Sunkin SM, Sutram M, Tam A, Teemer CD, Thaller C, Thompson CL, Varnam LR, Visel A, Whitlock RM, Wohnoutka PE, Wolkey CK, Wong VY, Wood M, Yaylaoglu MB, Young RC, Youngstrom BL, Yuan XF, Zhang B, Zwingman TA, Jones AR. Genome-wide atlas of gene expression in the adult mouse brain. Nature 445: 168–176, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li G, Olson JE. Cell volume modifies an ATP-sensitive anion conductance in cultured hippocampal astrocytes. Adv Exp Med Biol 559: 405–406, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li G, Olson JE. Extracellular ATP activates chloride and taurine conductances in cultured hippocampal neurons. Neurochem Res 29: 239–246, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Light DB, Capes TL, Gronau RT, Adler MR. Extracellular ATP stimulates volume decrease in Necturus red blood cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 277: C480–C491, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Light DB, Dahlstrom PK, Gronau RT, Baumann NL. Extracellular ATP activates a P2 receptor in Necturus erythrocytes during hypotonic swelling. J Membr Biol 182: 193–202, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lowry OH, Rosebrough NJ, Farr AL, Randall RJ. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem 193: 265–275, 1951. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ma HP, Zhou ZH, Liang YY, Saxena S, Warnock DG. Acidic ATP activates lymphocyte outwardly rectifying chloride channels via a novel pathway. Pflügers Arch 449: 96–105, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Masino SA, Latini S, Bordoni F, Pedata F, Dunwiddie TV. Changes in hippocampal adenosine efflux, ATP levels, and synaptic transmission induced by increased temperature. Synapse 41: 58–64, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.McGill JM, Yen MS, Basavappa S, Mangel AW, Kwiatkowski AP. ATP-activated chloride permeability in biliary epithelial cells is regulated by calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 208: 457–462, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Melani A, Turchi D, Vannucchi MG, Cipriani S, Gianfriddo M, Pedata F. ATP extracellular concentrations are increased in the rat striatum during in vivo ischemia. Neurochem Int 47: 442–448, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mendoza-Fernandez V, Andrew RD, Barajas-Lopez C. ATP inhibits glutamate synaptic release by acting at P2Y receptors in pyramidal neurons of hippocampal slices. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 293: 172–179, 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Meyer G, Rodighiero S, Guizzardi F, Bazzini C, Botta G, Bertocchi C, Garavaglia L, Dossena S, Manfredi R, Sironi C, Catania A, Paulmichl M. Volume-regulated Cl− channels in human pleural mesothelioma cells. FEBS Lett 559: 45–50, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mongin AA, Kimelberg HK. ATP potently modulates anion channel-mediated excitatory amino acid release from cultured astrocytes. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 283: C569–C578, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mongin AA, Kimelberg HK. ATP regulates anion channel-mediated organic osmolyte release from cultured rat astrocytes via multiple Ca2+-sensitive mechanisms. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 288: C204–C213, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Moore D, Chambers J, Waldvogel H, Faull R, Emson P. Regional and cellular distribution of the P2Y1 purinergic receptor in the human brain: striking neuronal localisation. J Comp Neurol 421: 374–384, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Moran-Jimenez MJ, Matute C. Immunohistochemical localization of the P2Y1 purinergic receptor in neurons and glial cells of the central nervous system. Brain Res Mol Brain Res 78: 50–58, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nagelhus EA, Amiry-Moghaddam M, Lehmann A, Ottersen OP. Taurine as an organic osmolyte in the intact brain: immunocytochemical and biochemical studies. Adv Exp Med Biol 359: 325–334, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nakazawa K, Inoue K, Inoue K. ATP reduces voltage-activated K+ current in cultured rat hippocampal neurons. Pflügers Arch 429: 143–145, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nilius B, Eggermont J, Voets T, Droogmans G. Volume-activated Cl− channels. Gen Pharmacol 27: 1131–1140, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.North RA Molecular physiology of P2X receptors. Physiol Rev 82: 1013–1067, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.North RA, Surprenant A. Pharmacology of cloned P2X receptors. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 40: 563–580, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.O'Neill WC Physiological significance of volume-regulatory transporters. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 276: C995–C1011, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Olson JE Osmolyte contents of cultured astrocytes grown in hypoosmotic medium. Biochim Biophys Acta 1453: 175–179, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Olson JE, Li GZ. Increased potassium, chloride, and taurine conductances in astrocytes during hypoosmotic swelling. Glia 20: 254–261, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Olson JE, Li GZ. Osmotic sensitivity of taurine release from hippocampal neuronal and glial cells. Adv Exp Med Biol 483: 213–218, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Olson JE, Martinho E Jr. Regulation of taurine transport in rat hippocampal neurons by hypo-osmotic swelling. J Neurochem 96: 1375–1389, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Palkovits M, Elekes I, Lang T, Patthy A. Taurine levels in discrete brain nuclei of rats. J Neurochem 47: 1333–1335, 1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Partridge LD, Valenzuela CF. Ca2+ store-dependent potentiation of Ca2+-activated non-selective cation channels in rat hippocampal neurones in vitro. J Physiol 521: 617–627, 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Pasantes-Morales H, Alavez S, Sanchez Olea R, Moran J. Contribution of organic and inorganic osmolytes to volume regulation in rat brain cells in culture. Neurochem Res 18: 445–452, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Pasantes-Morales H, Franco R, Ochoa L, Ordaz B. Osmosensitive release of neurotransmitter amino acids: relevance and mechanisms. Neurochem Res 27: 59–65, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Phillis JW, O'Regan MH. Evidence for swelling-induced adenosine and adenine nucleotide release in rat cerebral cortex exposed to monocarboxylate-containing or hypotonic artificial cerebrospinal fluids. Neurochem Int 40: 629–635, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ralevic V, Burnstock G. Receptors for purines and pyrimidines. Pharmacol Rev 50: 413–492, 1998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Robertson SJ, Ennion SJ, Evans RJ, Edwards FA. Synaptic P2X receptors. Curr Opin Neurobiol 11: 378–386, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Rodrigues RJ, Almeida T, Richardson PJ, Oliveira CR, Cunha RA. Dual presynaptic control by ATP of glutamate release via facilitatory P2X1, P2X2/3, and P2X3 and inhibitory P2Y1, P2Y2, and/or P2Y4 receptors in the rat hippocampus. J Neurosci 25: 6286–6295, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Roe MW, Moore AL, Lidofsky SD. Purinergic-independent calcium signaling mediates recovery from hepatocellular swelling: implications for volume regulation. J Biol Chem 276: 30871–30877, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Romanello M, Pani B, Bicego M, D'Andrea P. Mechanically induced ATP release from human osteoblastic cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 289: 1275–1281, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Roy G, Banderali U. Channels for ions and amino acids in kidney cultured cells (MDCK) during volume regulation. J Exp Zool 268: 121–126, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Rubera I, Tauc M, Bidet M, Verheecke-Mauze C, De Renzis G, Poujeol C, Cuiller B, Poujeol P. Extracellular ATP increases [Ca2+]i in distal tubule cells. II. Activation of a Ca2+-dependent Cl− conductance. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 279: F102–F111, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Solis JM, Herranz AS, Herreras O, Lerma J, Martin del Rio R. Does taurine act as an osmoregulatory substance in the rat brain? Neurosci Lett 91: 53–58, 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Stover JF, Unterberg AW. Increased cerebrospinal fluid glutamate and taurine concentrations are associated with traumatic brain edema formation in rats. Brain Res 875: 51–55, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Su H, Alroy G, Kirson ED, Yaari Y. Extracellular calcium modulates persistent sodium current-dependent burst-firing in hippocampal pyramidal neurons. J Neurosci 21: 4173–4182, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Swanson KD, Reigh C, Landreth GE. ATP-stimulated activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinases through ionotrophic P2X2 purinoreceptors in PC12 cells. Difference in purinoreceptor sensitivity in two PC12 cell lines. J Biol Chem 273: 19965–19971, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Tanaka E, Uchikado H, Niiyama S, Uematsu K, Higashi H. Extrusion of intracellular calcium ion after in vitro ischemia in the rat hippocampal CA1 region. J Neurophysiol 88: 879–887, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Thomas EJ, Gabriel SE, Makhlina M, Hardy SP, Lethem MI. Expression of nucleotide-regulated Cl− currents in CF and normal mouse tracheal epithelial cell lines. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 279: C1578–C1586, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Van der Wijk T, De Jonge HR, Tilly BC. Osmotic cell swelling-induced ATP release mediates the activation of extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase (Erk)-1/2 but not the activation of osmo-sensitive anion channels. Biochem J 343: 579–586, 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Verbalis JG, Gullans SR. Hyponatremia causes large sustained reductions in brain content of multiple organic osmolytes in rats. Brain Res 567: 274–282, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Zhu Y, Kimelberg HK. Cellular expression of P2Y and beta-AR receptor mRNAs and proteins in freshly isolated astrocytes and tissue sections from the CA1 region of P8–12 rat hippocampus. Brain Res Dev Brain Res 148: 77–87, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]