In the last decade, great progress has been made in dissecting the molecular mechanisms of Acute Kidney Injury (AKI; Also known as Acute Renal Failure, ARF)); however, translation of these findings to therapeutics of clinical utility has lagged. Development of therapeutics for AKI is has been slow and garnered limited industry interest because AKI is poorly characterized and difficult to diagnose early. Additional challenges include an inability to predict severity, measure progression, or response to therapy, all of which add complexity and risk to clinical trials. A standard definition of AKI is being developed, which will facilitate progress greatly. However, the over-reliance on serum creatinine as a marker of renal function and injury and the absence of additional disease markers has hampered clinical trials for AKI. Serum creatinine in AKI has poor sensitivity and specificity; patients are not in steady state, hence serum creatinine lags behind both renal injury and renal recovery. Conventional urine markers (casts, fractional excretion of sodium) are non-specific and insensitive. Reliance on traditional markers slows recognition of AKI and hence delays nephrologic consultation and discontinuation of nephrotoxic agents, and complicates drug development.

Clinical trials are hampered by the lack of markers to diagnose AKI early, when drugs might be effective, and by the inability to ensure equality of the treatment and placebo groups because this very heterogeneous patient population cannot be stratified during randomization. All AKI clinical trials, but especially Phase 2 dose discovery and proof of concept studies, would be improved by sensitive tools to assess outcomes and response to therapy that, unlike changes in serum creatinine, are independent of volume status and occur more frequently than the hard clinical outcomes of death or dialysis. Because the correct patients are not enrolled or the outcome measures are inaccurate or slowly track the disease, the noise and hence size, cost, and risk of failure of clinical studies is increased.

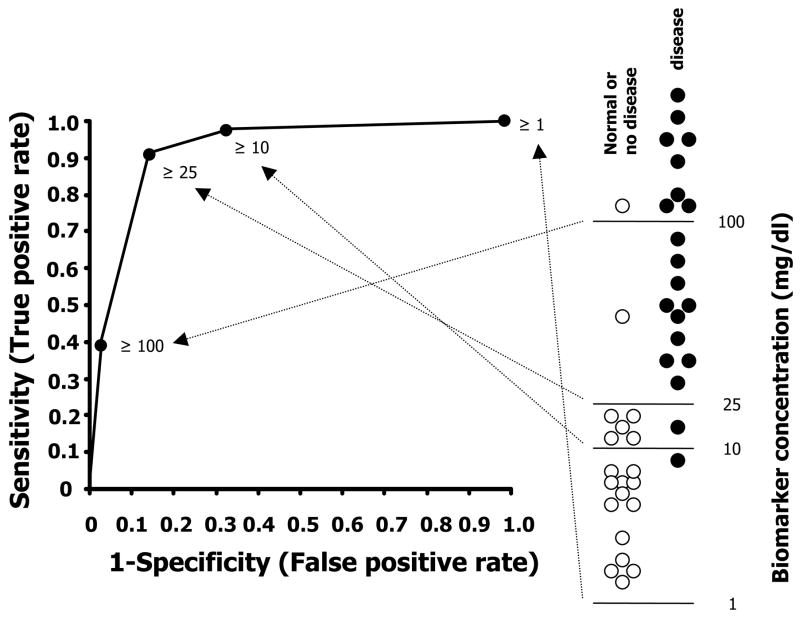

Biomarkers and surrogate markers (defined below) can supply some of the needed information, driving efforts to develop new troponin-like markers and associated methods of monitoring AKI (Figure 1) (1). Of particular interest are biomarkers that aid in 1) diagnosing AKI and differentiating AKI from other forms of renal injury, 2) early detection of AKI to improve testing of early disease pre-emption strategies in situations where the overall incidence of AKI is low (i.e., post-cardiac surgery) or the disease is complicated (sepsis), 3) ascertaining the etiology and site of renal injury to select appropriate therapy, 4) predicting the severity of AKI to aid in stratifying patients in clinical trials, assessing who needs drug treatment or dialysis, and addressing “when to start renal replacement therapy”, and 5) monitoring the effects of an intervention (intermediate or surrogate outcome biomarkers) for initial dosing and Phase 2 proof of concept clinical trials, and even larger Phase 3 efficacy/safety trials.

Figure 1.

Different types of biomarkers for acute kidney injury (AKI). Curves show typical disease trajectories for different hypothetical patients with AKI. Biomarkers may play several roles, including accurate diagnosis, early detection, monitoring therapy, or predicting the severity of AKI.

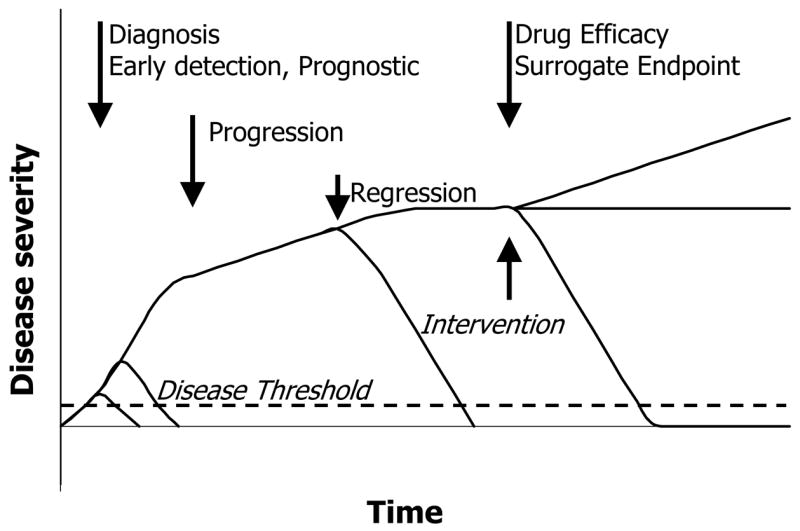

The classic biomarker development paradigm is to search for individual disease-specific blood or urine tests (e.g.., beta-HCG for pregnancy or troponin for myocardial infarction). However, a complex disease such as AKI will likely require a panel of biomarkers that will be used in conjunction with other clinical parameters to form a “diagnostic instrument” that can distinguish different sub-types of AKI (pre-renal azotemia, obstruction, ischemia, sepsis, toxin), and differentiate them from closely related diseases (lupus nephritis, acute glomerulonephritis) (Figure 2). New high throughput screening approaches are being applied to accelerate the discovery process. One hopes that in the next decade, AKI will no longer be defined by changes in serum creatinine level, but rather multiple biomarkers and clinical parameters that form etiology specific signatures which will clearly discern sub-types of AKI and closely related disorders within minutes to hours, rather than days, after renal injury.

Figure 2.

Multiple biomarkers can improve the specificity of diagnosis. Clinical information often does not differentiate AKI from other renal diseases. Biomarkers add new dimensions that allow discrimination among several conditions that cannot be distinguished by clinical assessment. (A) Clinical data may not completely differentiate AKI from SLE, AGN and UTI. (B) Biomarker panel (biomarkers A and B) further distinguishes among sub-types of AKI.

Development of biomarkers for AKI is a rapidly evolving field. We will define the types and desired characteristics of AKI biomarkers, review general principles of biomarker discovery process, analyze the strengths and weaknesses of AKI biomarkers that have been tested in humans, discuss several emerging techniques, and suggest what is required for further progress.

Biomarkers can be characterized as biological parameters that can be objectively measured and evaluated as an indicator of normal biological processes, pathogenic processes, or a pharmacological response to therapeutic intervention. Examples include blood pressure, lipids, proteins, mRNA expression profiles, imaging methods, or electrical signals. Biomarkers that faithfully track disease including response to therapy and recurrence are called surrogate outcome biomarkers, and are highly sought after. In the kidney, biomarkers may either directly measure renal structural damage (similar to troponin), or be integral to the disease pathway (cholesterol or blood pressure) so the biomarker result cannot be dissociated from the hard clinical outcome it is meant to track. Thus, measurement of the surrogate biomarker can substitute for the defined clinical endpoint, and greatly speed the drug discovery process by, among other things, shortening the length and size of a clinical trial. However, validation of a surrogate endpoint is extremely difficult and costly.

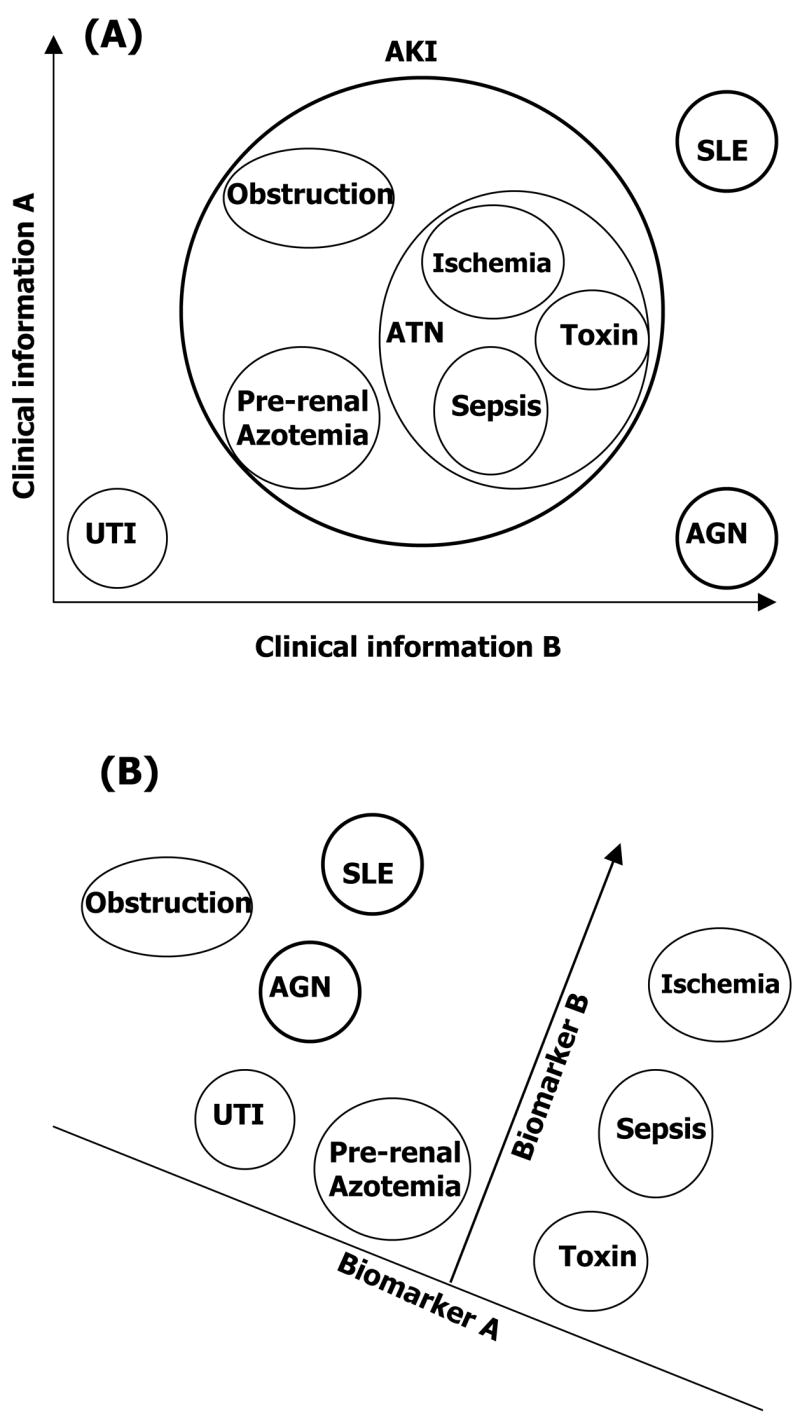

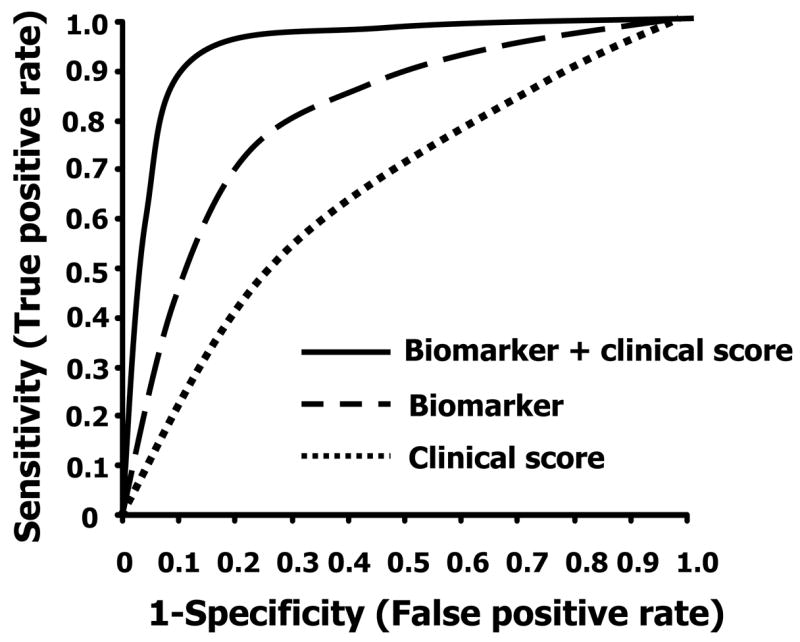

Clinically applicable biomarkers are accurate, relatively non-invasive and easy to perform tests that can be done at the bedside or in a clinical laboratory (1). The most desirable tests involve a blood or spot urine specimen, can be measured serially, have a fast turn-around, and does not degrade over time. On a more practical clinical level, an ideal biomarker must be better, faster, and cheaper (more cost-effective) than current techniques. A useful AKI biomarker will be easy and rapidly measured by a standardized clinical assay, validated by prospective studies to have a high predictive ability (both sensitive and specific for AKI), additive to conventional clinical observations, and cost-effective. The specificity (i.e., lack of cross-reactivity with other non-AKI injuries) must be high to avoid expensive or hazardous additional diagnostic or therapeutic interventions (1). Sensitivity is essential, especially for early detection biomarkers. A wide dynamic range is desirable since it provides the capacity to determine the timing or severity of injury, rather than interpretation as a binomial yes/no answer. It is critical to establish the cut-off value that distinguishes the normal from abnormal (Figure 3A). The performance of a biomarker at a variety of cut-off values can be graphically displayed as a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve, which graphs the specificity and sensitivity associated with each cut-off value. Thus, there is usually a trade-off between sensitivity and specificity of a diagnostic test. The overall predictive ability of biomarker is often measured by the area under the ROC curve (AUC). A cut-off point closest to the upper left-hand corner of ROC curve best differentiates disease from normal with the highest sensitivity and specificity. However, it is usually not feasible to correctly diagnose disease from normal correctly using a single biomarker (Figure 3B). Individual biomarkers rarely have an AUC of greater than 0.80. An AUC of 0.80 for an individual biomarker is too low for clinical utility; however, when combined with clinical information and/or the results of other biomarkers, the AUC of the diagnostic panel should approach 1.0.

Figure 3.

Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves and Synergy of biomarker and clinical information. (A) ROC curve is used to measure the performance (predictive ability) of diagnostic instruments. The sensitivity and specificity is calculated at a variety of cutoff values. The area under ROC curve (AUC) evaluates the overall quality of the diagnostic instrument. The closer the curve gets to the upper left hand corner, the better the clinical utility to detect disease while discriminating between disease and nondisease. The dashed line shows the performance of a random diagnostic test (coin toss; AUC 0.5). A perfect biomarker should have an AUC of one. The best cutoff value (25 in this example) is generally the point closest to upper left-hand corner of ROC curve, which provides the highest sensitivity and specificity. (B) A diagnostic instrument consisting of multiple biomarkers, or biomarker(s) used in conjunction with clinical information will outperform a single biomarker.

The biomarker discovery process has been described by Hewitt et al. The common steps in the development of biomarkers has been divided into planning, discovery, validation, and commercialization phases (1). The planning phase is similar to that used in planning a clinical study, which uses the current state of knowledge to frame the clinical question that the biomarker will address (for example, provide critical information for early detection, prediction, therapeutic management, or prognosis), then develops the experimental pathway/protocol including animal or human sample sets, details of sample collection and timing, methodology for biomarker discovery and subsequent validation. Biomarkers are typically discovered using transcriptomic (mRNA) or proteomic (protein) methods that subtract “disease” from “normal” using animal models (ischemia, toxins, sepsis). Typically, the discovery process generates a plethora of potential biomarkers that are then winnowed down during the validation phase (described in Pepe et al) (2). Often, a crude research assay (western blot) is used in the first validation study to determine if the disease can be detected in a small cohort (typically 10–20 patients) with established disease, and can be distinguished from normal and diagnostically challenging situations (pre-renal, obstruction, CKD) (Table 1). A confirmatory study should be carried out on an independent sample set containing a modest number of normal and diseased samples, with calculation of the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC). If several biomarkers are measured at once, candidates can then be ranked based on the AUC value. Next, a clinical assay must be developed that is optimized or “hardened” so that it can be reproducibly performed at multiple sites. The reproducibility and portability are tested at multiple labs and sites to determine if the biomarker assay is suitable for widespread usage. Promising biomarkers are then tested to determine if they detect disease before it is clinically apparent and their performance characteristics evaluated (screen positive criteria, time before clinical diagnosis, sensitivity, specificity, AUC). A prospective screening study is then performed to determine the detection rate and false referral rate, followed by commercialization and introduction into routine clinical care. A final stage, rarely performed, is to determine if the biomarker can reduce disease burden or resource utilization. This daunting process is needed to ensure the clinical validity of the biomarker.

Table 1.

Testing of new biomarkers in human AKI

| Name | Differentiate from AKI | Diagnosis of established AKI (AUC) | Early detection of predictable AKI | Early detection of ICU AKI | Predict severity | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-renal | CKD | UTI | Renal cancer | Situation | When | AUC | Cohort | when | AUC | Outcome | AUC | |||

| NGAL(9, 16–18, 25, 29) | ? | yes | no | ? | 0.75~0.83 | CPB

DGF |

2 hrs

day 0 |

0.998

0.90 |

RRT | - | ||||

| KIM-1 (8–11) | Yes | yes | yes | no | 0.94~0.99 | CPB | 2 hrs | 0.879 | RRT mortality | 0.655

0.650 |

||||

| IL-18 (23–25) | Yes | yes | yes | ? | 0.95 | CPB

DGF |

6 hrs

24 hrs |

0.72 | ARDS | 24 hrs | 0.73 | mortality | ||

| Cystatin C | Urine (3, 30) | ? | no | ? | ? | RRT | 0.92 | |||||||

| Serum (7, 31) | no | 0.99 | ICU

ICU |

24hrs

48hr |

0.97

0.82 |

Mortality | 0.624 | |||||||

| NHE3(21) | Yes | ? | ? | ? | ? | |||||||||

| NAG (9, 10, 32) | No | yes | yes | ? | 0.94~0.99 | CPB | 2 hrs | 0.61 | RRT mortality | 0.698 0.712 | ||||

| MMP-9 (9) | No | yes | no | ? | 0.77 | - | ||||||||

ARDS: Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome; CKD: chronic kidney disease; CPB: cardiopulmonary bypass; DGF: delayed graft function; ICU: intensive care unit; AUC: area under receiver operating characteristic curve; RRT: renal replace treatment; UTI: urinary tract infection

At the resent time the AKI biomarker field is exciting and is advancing very rapidly. Table 1 contains a summary of the most promising serum and urinary biomarkers for AKI, including some preliminary studies published only in abstract form and not yet subjected to peer-review. Many of these markers have only been applied to a small number of patients, so all the biomarker performance data is quite preliminary. Most of biomarkers require the development of a robust hardened clinical assay, followed by repeat determination of the biomarker performance (sensitivity and specificity). More extensive clinical evaluation of all these markers in broad, clinically relevant populations will be required

Cystatin C is a 13kD cysteine protease inhibitor protein that is released at a constant rate by all nucleated cells into the plasma, and hence, does not need to be adjusted for age, gender, race, or muscle mass. It is freely filtered by the glomerulus, and completely reabsorbed and not secreted, like creatinine, in the tubules. By virtue of these properties, Cystatin C overcomes many of the problems that plague creatinine. Cystatin C is not affected by routine clinical storage conditions or common interfering substances, and a clinically approved automated immunonephelometric assay is widely available (3). Cystatin C appears to predict renal function (GFR) at least as well as creatinine in chronic kidney disease, and better than creatinine in AKI (4) (5), and predicts the risk of AKI-associated cardiovascular morbidity and mortality (6). In 85 patients at high risk to develop AKI in the ICU, a 50% increase in serum cystatin C predicted AKI one to two days before serum creatinine with AUC of 0.97 and 0.82 respectively (7), and was moderately good predicting the need for renal replacement therapy one day later with a AUC of 0.75 (3). However, like other functional markers, cystatin c cannot differentiate among different causes of AKI (pre-renal, obstructive, ATN).

Kidney injury molecule-1 (KIM-1) was the first renal biomarker discovered using high throughput screening methods. KIM-1 is an orphan trans-membrane receptor of unknown function that is induced to very high levels in the proximal tubule after ischemic and nephrotoxic injury. KIM-1 is subsequently proteolytically clipped and the extracellular (luminal) domain is shed into the urine (8). KIM-1 has only been evaluated in small number of human patients. In a preliminary study of 40 patients, only 9 of which had AKI, urinary KIM-1 could distinguish ischemic ATN from pre-renal azotemia and CKD. It was not detected in contrast nephropathy (8). In a modestly larger unpublished study of 67 subjects presented at ASN in 2005, KIM-1 could distinguish AKI from CKD and normal with an AUC of 0.94; it performed better than NGAL and MMP-9 (9) (Table 1). In 47 patients undergoing abdominal aortic aneurysm repair, KIM-1 increased 12 hrs after surgery but well before serum creatinine, and also modestly predicted the need for dialysis even after adjustment for disease severity and gender (10, 11). Urinary KIM-1 is increased in patients with renal carcinoma (12), but this should not interfere with use as an AKI marker. A more robust clinical assay is under development (13).

Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL), a 25kDa protein bound to gelatinase originally described in neutrophils (14), and has a complicated biology. Circulating NGAL (perhaps from the liver) is reabsorbed by the proximal tubule. Following ischemic injury, NGAL secretion is rapidly induced in the thick ascending limb and can be detected in the urine (15, 16). Exogenous NGAL protects against ischemic injury in mice (16). Urinary NGAL increased 100-fold in patients with ischemic and septic AKI (16) and a high level of urinary NGAL predicted the onset of AKI 2 hours after cardiopulmonary bypass in children undergoing cardiac surgery –2–4 days before AKI was identified by changes in serum creatinine (17). All of the 20 children who developed AKI and 50 of 51 children without AKI were correctly identified, with amazing sensitivity (100%), specificity (98%), and an AUC value of 0.999, what was much better and faster than that of IL-18 (described below) measured on the same samples (AUC 0.72 at 6 hrs). None of the children required dialysis, so the clinical value of such early detection is uncertain. Serum NGAL was not as predictive, but similar to that of a typical biomarker (AUC of 0.91). However, use of urinary NGAL to detect established AKI in adults with more typical multi-factorial AKI was 0.75–0.83, perhaps because NGAL is increased in patients with systemic or urinary tract infections (potentially related to neutrophil release of NGAL). NGAL also predicted delayed graft function in two cohorts (18, 19). NGAL appears to work better currently in uncomplicated patient population than in more seriously ill patients; however more studies are needed.

Sodium/hydrogen exchanger isoform 3 (NHE3) is the most abundant apical membrane sodium transporter in the proximal tubule. This structural protein is shed into the urine following injury, hence conceptually similar to troponin for myocardial infarction. Urinary NHE3 is shed into the urine via exosomes, small membrane vesicles that contain a small amount of cytoplasm (20). In a well performed study of 68 ICU patients (54 with AKI), urinary membrane NHE3 could differentiate ATN from pre-renal azotemia, obstructive nephropathy, and UTI (21). Urinary NHE3 outperformed FENa in differentiating intrinsic from pre-renal azotemia. The current assay for NHE3 is too complex for use in a clinical laboratory, requiring ultracentrifugation and western blot analysis. Whereas the diagnostic separation of AKI form other acute renal diseases was impressive, a clinical assay must be developed and tested in a larger population of patients with acute and chronic renal diseases.

Interleukin-18 (IL-18) is a pro-inflammatory cytokine that is cleaved to the mature form by caspase-1 in injured proximal tubules and released into urine after ischemia (22). Neutralizing IL-18 antibodies reduce ischemic renal injury in mice (22). Urinary IL-18 increased significantly in 14 patients with AKI compared to 36 normal subjects and patients with pre-renal azotemia, urinary tract infection, chronic renal insufficiency, and nephritic syndrome however no AUC value was reported. Urinary IL-18 collected on day 0 after transplantation in 22 patients and was increased markedly in delayed graft function compared with prompt graft function (AUC 0.95) (23). Elevation of urinary IL-18 could predict AKI one day before creatinine in 138 patients with Adult Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS) with a AUC of 0.73 (24), and elevated urinary IL-18 was an independent predictor of mortality (24). NGAL and IL-18 are early and sequential biomarkers in children undergoing cardiac surgery; NGAL peaks at 2 hrs that is followed by the IL-18 peak at 12 hrs, in marked contrast the 48 hrs needed to detect AKI by serum creatinine. Urinary IL-18 has a lower AUC (0.74 at 12 hrs) than NGAL (0.99 at 2 hrs). While a biomarker panel with these two might be helpful late in the course of borderline cases, it would be difficult to demonstrate that both biomarkers are needed for early detection hours after injury – since NGAL alone was as predictive. However, IL-18 and NGAL together improved the prediction of number days of AKI after pediatric surgery (25). Why IL-18 appears to be a better diagnostic biomarker than an early detection marker remains to be determined; however, it is anticipated to add value as part of a panel of biomarkers.

NAG and MMP-9. Both urinary NAG (N-acetyl-beta-D-glucosaminidase) and MMP-9 (matrix metalloproteinase-9) have been implicated as markers for proximal tubule injury. In a small study, urinary secretion of both markers is increased in AKI and they both can differentiate AKI from CKD in a small study. Urinary NAG had a better sensitivity and specificity in detect existing AKI. Although promising, additional studies are necessary to better evaluate these makers (9).

Although all of the previously described biomarkers show great promise in improving the early recognition of AKI, it is anticipated additional biomarkers are essential to reducing the morbidity and mortality of AKI. The approaches discussed here are being applied to a broad spectrum of biomarker discovery efforts for renal, as well as other disorders.

All of the previously described studies measured biomarkers individually (one at a time). The development of a biomarker panel containing 2–20 biomarkers (multiplex panel) might be facilitated by higher throughput systems that can measure simultaneously a large number of proteins from a small (100–500 uL) volume of urine. For example, multiple (between 10–20) analytes can be measured simultaneously using a particle-based flow system where different “color” beads measure different proteins. Rabb et al used this system in animal studies to determine that three cytokines (IL-1β, RANTES, and IFN-π) were increased 6 weeks after ischemia/perfusion injury (26). Multiplex assays have unresolved issues including issues of sample handling and labeling, cross reactivity of analytes, dynamic range, interpretation, and validation of results. It is likely that multiplex assays of fewer than 10 biomarkers will be based on determination of the predictive value of each biomarker individually, and demonstrating the additive effects of the multiple biomarkers. For multiplex assays in excess of 10 biomarkers, the method of validating these signatures becomes more complex as the number of possible combinations for each analyte makes validation individually impractical.

A great deal has been written about new biomarker discovery platforms, including expression microarrays, protein and antibody arrays and mass spectrometry based approaches to define disease specific signatures. These approaches are currently being applied to AKI. These approaches are powerful discovery tools for screening the patient samples for potential biomarkers; however reduction of these technologies to patient care awaits the development of new instrumentation. Although they may well see clinical introduction in 3 to 5 years, validation schema and regulatory pathways remain uncertain.

Current studies of biomarkers in AKI have so far been performed in relatively small cohorts, with different definitions of AKI, so that comparisons among biomarkers must be made cautiously. It is critical that all candidate biomarkers be simultaneously tested in large cohorts of patients, using an identical clinical definition of AKI. Combining biomarkers (biomarker panel) with relevant clinical information can create a powerful diagnostic tool (Figures 2–3). The utility of these strategies must also be measured against the clinical endpoints of dialysis and mortality. “Cause specific” biomarkers are needed since none of the current biomarkers appear to show specificity to particular types of AKI (Sepsis, ischemia, nephrotoxins, etc.)

The diagnostic goal is to distinguish renal AKI (ATN) from pre-renal azotemia, obstruction, UTI, and CKD. Although studies are small, several biomarkers already perform better than serum creatinine and other traditional urinary markers. KIM-1, IL-18, NAG, and perhaps NHE3 show good promise (AUC values above 0.9 upon initial testing), with NGAL and IL-18 somewhat lower on the list, perhaps related to non-specific increases with infection or other systemic diseases. However, the AUCs were calculated using different diagnostic criteria for AKI, so cross study comparisons are fraught with difficulty. NHE3 performs better than FENa, a previously suggested gold standard, demonstrating the challenge of defining the clinical diagnosis of AKI.

NGAL and KIM-1 are increased in urine very early (2 hr) after injury, followed by IL-18 at 12 hrs, and hence may serve as early detection biomarkers, at least in well-defined clinical settings. The unprecedented performance of NGAL following cardiac surgery in children is surprising, since most single biomarkers do not have an AUC above 0.80. This will need to be studied in an independent cohort, using a more robust assay for NGAL. The sequential increase in NGAL followed by IL-18 is reminiscent of troponin, CPK, and LDH for myocardial infarction, and raises hope of discovering a set of biomarkers that determines time since injury. Both NGAL and KIM-1 performed well in predicting delayed graft function after renal transplantation; a study of both together might show significant synergy. Animal models and some human studies have shown that some markers detect sub-clinical disease (biomarker positive, casts present, but creatinine not elevated). The clinical significance of a small elevation in a candidate biomarker must be defined, just as the clinical significance of small elevations in serum creatinine has only recently been determined (27).

AKI occurring in the intensive care unit (ICU) setting is an especially important problem. The renal function marker serum cystatin C performed quite well in predicting AKI 1–2 days before a rise in creatinine. However, the dramatic fall off in performance (AUC) of the injury biomarkers (KIM-1, IL-18) when moving from simple AKI (that mimics commonly used ischemic animal model) to more complex AKI developing in the ICU indicates the difficulty of finding adequate biomarkers for human multi-factorial AKI.. The ICU environment is quite complex, with overlapping waves of injury, confounding systemic disease in injury, and massive volume shifts. Hence, the demands on the candidate biomarkers are higher – diagnosis in an ambiguous setting, distinguish the severity of AKI, differentiate it from the other systemic effects, and predict need for renal replacement or other supportive therapy. Prediction of onset of AKI is important, since it might reflect a molecular injury clock that indicates how long the patient has been ill with their underlying disease, and allow rapid institution of therapy. For this, cystatin C already holds great promise, but needs to be tested in an independent study.

Finally, biomarkers for the severity of AKI, the need for renal replacement therapy, and prediction of mortality from and with AKI are being examined, but this will be more difficult to obtain. A combination of two biomarkers (NGAL and IL-18) did predict number of days of AKI, suggesting that a biomarker panel, likely including clinical information, may be needed for severity measures. A biomarker that can be used to track therapeutic responsiveness is critical to drug discovery. It is surprising that none of the current biomarkers have been tested in any AKI animal models to see if the biomarker tracks renal injury. These studies are critically needed.

In summary, advances in biomedical technology and a better appreciation of disease biomarkers have fueled rapid progress in recent years to develop AKI biomarkers. These early discoveries show great promise, but there is much work ahead, especially with validation and adaptation toward practical assays. Validation of the specificity of the biomarkers for types of AKI, other renal diseases, and non-renal diseases in much larger cohorts is essential for adequate statistical power. Biomarkers will not tangibly improve patient care, unless rapid, robust assays can be routinely performed at the bedside (dipstick) or in a clinical laboratory. Much has yet to be explored on how to combine biomarkers with each other and with clinical information; for example, a biomarker may not distinguish between AKI and another disease, but a complementary biomarker may be used so that the inherent weakness of each individual biomarker can be minimized. Biomarker panels that combine information about function, injury, and prognosis should improve decision making, from patient stratification to therapeutic strategies. As biomarkers are developed one must ask whether each biomarker provides additional clinically relevant information. The greatest clinical challenges in AKI are in the ICU setting, where biomarkers are most needed that determine the nature of the AKI, measure severity, and predict need for dialysis.

These challenges are difficult to surmount in an individual laboratory, and will require widespread collaboration. There are many barriers in the biomarker discovery/translation pathway that are common across disease groups, including quality control, reference standards, multi-center studies of large cohorts, and intellectual property issues (28).

I is likely that diagnostic and early detection AKI biomarkers should be available for use in laboratory research and clinical studies relatively soon. The goal remains to diagnose AKI within hours rather than within days, as well as differentiate the types of AKI, so that the appropriate interventions can be started rapidly. These advances should dramatically increase the likelihood of finding drugs that prevent, pre-empt, and/or treat AKI.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, NIDDK and NCI.

References

- 1.Hewitt SM, Dear J, Star RA. Discovery of protein biomarkers for renal diseases. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15:1677–89. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000129114.92265.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pepe MS, Etzioni R, Feng Z, Potter JD, Thompson ML, Thornquist M, Winget M, Yasui Y. Phases of biomarker development for early detection of cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93:1054–61. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.14.1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Herget-Rosenthal S, Poppen D, Husing J, Marggraf G, Pietruck F, Jakob HG, Philipp T, Kribben A. Prognostic value of tubular proteinuria and enzymuria in nonoliguric acute tubular necrosis. Clin Chem. 2004;50:552–8. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2003.027763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dharnidharka VR, Kwon C, Stevens G. Serum cystatin C is superior to serum creatinine as a marker of kidney function: a meta-analysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002;40:221–6. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2002.34487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Herget-Rosenthal S, Pietruck F, Volbracht L, Philipp T, Kribben A. Serum cystatin C--a superior marker of rapidly reduced glomerular filtration after uninephrectomy in kidney donors compared to creatinine. Clin Nephrol. 2005;64:41–6. doi: 10.5414/cnp64041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shlipak MG, Sarnak MJ, Katz R, Fried LF, Seliger SL, Newman AB, Siscovick DS, Stehman-Breen C. Cystatin C and the risk of death and cardiovascular events among elderly persons. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:2049–60. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Herget-Rosenthal S, Marggraf G, Husing J, Goring F, Pietruck F, Janssen O, Philipp T, Kribben A. Early detection of acute renal failure by serum cystatin C. Kidney Int. 2004;66:1115–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00861.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Han WK, Bailly V, Abichandani R, Thadhani R, Bonventre JV. Kidney Injury Molecule-1 (KIM-1): a novel biomarker for human renal proximal tubule injury. Kidney Int. 2002;62:237–44. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Han WK, Waikar SS, Alinani A, Curhan GC, Bonventre JV. Urinary Biomarkers for Detection of Acute Kidney Injury. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:316A. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liangos O, Han WK, Wald R, Perianayagam MC, Balakrishnan VS, MacKinnon RW, Warner K, Symes JF, Li L, Kouznetsov A, Pereira BJG, Bonventre JV, Jaber BL. Urinary Kidney Injury Molecule-1 (KIM-1) and N-Acetyl(β)-D-Glucosaminidase (NAG) Levels in Patients Undergoing Cardiac Surgery with Cardiopulmonary Bypass (CPB) J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:318A. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liangos O, Han WK, Wald R, Perianayagam MC, Balakrishnan VS, MacKinnon RW, Li L, Pereira BJG, Bonventre JV, Jaber BL. Urinary Kidney Injury Molecule-1 Levels Are Associated with Renal Replacement Therapy (RRT) and Death in Acute Renal Failure (ARF) J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:318A. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Han WK, Alinani A, Wu CL, Michaelson D, Loda M, McGovern FJ, Thadhani R, Bonventre JV. Human kidney injury molecule-1 is a tissue and urinary tumor marker of renal cell carcinoma. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:1126–34. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2004070530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vaidya VS, Ramirez V, Bobadilla N, Bonventre JV. A Microfluidics Based Assay To Measure Kidney Injury Molecule-1 (Kim-1) in the Urine as a Biomarker for Early Diagnosis of Acute Kidney Injury. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:192A. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kjeldsen L, Cowland JB, Borregaard N. Human neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin and homologous proteins in rat and mouse. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1482:272–83. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4838(00)00152-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mishra J, Ma Q, Prada A, Mitsnefes M, Zahedi K, Yang J, Barasch J, Devarajan P. Identification of neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin as a novel early urinary biomarker for ischemic renal injury. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14:2534–43. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000088027.54400.c6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mori K, Lee HT, Rapoport D, Drexler IR, Foster K, Yang J, Schmidt-Ott KM, Chen X, Li JY, Weiss S, Mishra J, Cheema FH, Markowitz G, Suganami T, Sawai K, Mukoyama M, Kunis C, D’Agati V, Devarajan P, Barasch J. Endocytic delivery of lipocalin-siderophore-iron complex rescues the kidney from ischemia-reperfusion injury. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:610–21. doi: 10.1172/JCI23056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mishra J, Dent C, Tarabishi R, Mitsnefes MM, Ma Q, Kelly C, Ruff SM, Zahedi K, Shao M, Bean J, Mori K, Barasch J, Devarajan P. Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) as a biomarker for acute renal injury after cardiac surgery. Lancet. 2005;365:1231–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)74811-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parikh C, Jani A, Mishra J, Ma Q, Kelly C, Edelstein CL, Devarajan P. Urine NGAL Is a Novel Early Predictive Biomarker for Delayed Graft Function. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:243A. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01352.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kunis CL, Kirkham JC, Nickolas TL, Mori K, Barasch N, Devarajan P, Barasch J. Ngal Predicts Delayed Graft Function (DGF) in Renal Transplant (RT) Recipients. 2005;16:243A. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pisitkun T, Shen RF, Knepper MA. Identification and proteomic profiling of exosomes in human urine. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:13368–73. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403453101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.du Cheyron D, Daubin C, Poggioli J, Ramakers M, Houillier P, Charbonneau P, Paillard M. Urinary measurement of Na+/H+ exchanger isoform 3 (NHE3) protein as new marker of tubule injury in critically ill patients with ARF. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003;42:497–506. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(03)00744-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Melnikov VY, Ecder T, Fantuzzi G, Siegmund B, Lucia MS, Dinarello CA, Schrier RW, Edelstein CL. Impaired IL-18 processing protects caspase-1-deficient mice from ischemic acute renal failure. J Clin Invest. 2001;107:1145–52. doi: 10.1172/JCI12089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Parikh CR, Jani A, Melnikov VY, Faubel S, Edelstein CL. Urinary interleukin-18 is a marker of human acute tubular necrosis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;43:405–14. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2003.10.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Parikh CR, Abraham E, Ancukiewicz M, Edelstein CL. Urine IL-18 is an early diagnostic marker for acute kidney injury and predicts mortality in the intensive care unit. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:3046–52. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005030236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Parikh C, Mishra J, Ma Q, Kelly C, Dent C, Devarajan P, Edelstein CL. NGAL and IL-18: Novel Early Sequential Predictive Biomarkers of Acute Kidney Injury after Cardiac Surgery. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:45A. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Burne-Taney MJ, Yokota N, Rabb H. Persistent renal and extrarenal immune changes after severe ischemic injury. Kidney Int. 2005;67:1002–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00163.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chertow GM, Burdick E, Honour M, Bonventre JV, Bates DW. Acute kidney injury, mortality, length of stay, and costs in hospitalized patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:3365–70. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2004090740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bast RC, Jr, Lilja H, Urban N, Rimm DL, Fritsche H, Gray J, Veltri R, Klee G, Allen A, Kim N, Gutman S, Rubin MA, Hruszkewycz A. Translational crossroads for biomarkers. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:6103–8. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Trachtman T, Christen E, Patrick J, Devarajan P. Urinary Excretion of Neutrophil Gelatinase-Associated Lipocalcin (NGAL) in Diarrhea-Associated Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome (D+HUS) J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:316A. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Uchida K, Gotoh A. Measurement of cystatin-C and creatinine in urine. Clin Chim Acta. 2002;323:121–8. doi: 10.1016/s0009-8981(02)00177-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Artunc FH, Fischer IU, Risler T, Erley CM. Improved estimation of GFR by serum cystatin C in patients undergoing cardiac catheterization. Int J Cardiol. 2005;102:173–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2004.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liangos O, Wald R, Perianayagam MC, Han WK, Balakrishnan VS, MacKinnon RW, Li L, Pereira BJG, Bonventre JV, Jaber BL. Urinary N-Acetyl(β)-D-Glucosaminidase (NAG) Concentration Is Associated with Disease Severity and Outcomes in Acute Renal Failure (ARF) J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:317A. [Google Scholar]