Abstract

Background

The early signaling events in the development of necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) remain undefined. We have recently shown that the endotoxin (lipopolysaccharide, LPS) receptor Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) on enterocytes is critical in the pathogenesis of experimental NEC. Given that the membrane receptor CD14 is known to facilitate the activation of TLR4, we now hypothesize that endotoxemia induces an early up-regulation of CD14 in enterocytes, and that this participates in the early intestinal inflammatory response in the development of NEC.

Methods

IEC-6 enterocytes were treated with LPS(50ug/ml), and the subcellular localization of CD14 and TLR4 were assessed by confocal microscopy. C57/Bl6 or CD14−/− mice were treated with LPS(5mg/kg), while experimental NEC was induced using a combination of gavage formula feeding and intermittent hypoxia. CD14 expression was determined by SDS-PAGE and RT-PCR and IL-6 was quantified by ELISA and RT-PCR.

Results

Exposure of IEC-6 enterocytes to LPS led to an initial, transient increase in CD14 expression. The early increase in CD14 expression was associated with internalization of CD14 to a perinuclear compartment where increased colocalization with TLR4 was noted. The in vivo significance of these findings is suggested as treatment of mice with LPS led to an early increase in CD14 expression in the intestinal mucosa, while, the persistent endotoxemia of experimental NEC was associated with decreased CD14 expression within enterocytes.

Conclusions

LPS signaling in the enterocyte is marked by an early, transient increase in expression of CD14 and redistribution of the receptor. This process may contribute to the early activation of the intestinal inflammatory response which is observed in the development of NEC.

Keywords: toll-like receptor (TLR) 4, lipopolysaccharide (LPS), bacterial translocation, hypoxic stress, critical illness

INTRODUCTION

Necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) is the most frequent gastrointestinal cause of death in preterm infants (1, 2). Primarily a disease of prematurity, NEC has increased in incidence as our ability to support children suffering from otherwise fatal disease improves (3). NEC is characterized by local and systemic inflammation which may progress to intestinal necrosis and perforation, overwhelming sepsis and death (4). The pathophysiology of NEC is incompletely understood, yet recent evidence indicates this disease develops after an episode of stress to the intestinal barrier, leading to impaired healing and a prolonged breakdown of the gut barrier (5). This leads to bacterial translocation from the intestinal lumen and leukocyte activation, stimulating local and systemic cytokine release. Recent evidence has demonstrated increased levels of bacterial endotoxin (lipopolysaccharide, LPS) in infants with NEC, and higher levels of serum endotoxin have been found to be predictive of mortality (6). Interestingly, serum cytokine levels were highest near the onset of disease, highlighting a role for early LPS-mediated pro-inflammatory signaling as an early event in the development of NEC (6).

LPS stimulates pro-inflammatory signaling in enterocytes through an interaction with toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) (7, 8). Our group and the group of Caplan and colleagues have recently shown that TLR4 plays a key role in the development of experimental NEC in vivo, as animals with mutations in TLR4 were found to be protected from the development of this disease as compared to wild-type counterparts (9, 10). We have shown that the role of TLR4 in the pathogenesis of NEC involves an exacerbation of enterocyte injury and an inhibition of mucosal repair mechanisms (9). Expression of TLR4 was also found to be increased in the early stages of NEC (9, 10). LPS-dependent TLR4 activation is known to involve a family of co-receptors including MD2 and CD14(11). Although the exact nature of interaction between these molecules is not known, it is thought that LPS can be shuttled to MD2 by CD14, allowing for a direct interaction between LPS-bound MD2 and TLR4 (12, 13). Whereas both CD14-dependent and CD14-indepent activation of TLR4 has been documented, it is unclear what role, if any CD14 may play in the development of experimental NEC(14–16).

We now suggest a novel role for the LPS receptor CD14 in the pathogenesis of NEC. Specifically, we demonstrate that CD14 expression within enterocytes transiently increases after LPS exposure in vitro and in vivo, during which time a significant systemic inflammatory cytokine response is observed. This early up-regulation of CD14 is followed by a decrease in CD14 expression after prolonged LPS exposure in vitro and in vivo. Our data raise the possibility that transient alterations in CD14 responsiveness could contribute to the early signaling events observed in experimental NEC.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture, treatment, and reagents

The small intestinal enterocyte cell line IEC-6 was obtained from America Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA) and maintained in DMEM (with 4.5 g/1 of glucose) as described (17, 18). Where indicated, cells were treated with LPS (50µg/ml, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) for the indicated period of time. This concentration of LPS was determined as it corresponds to approximately 15–20 endotoxin units/ml as determined by limulus assay, which is within the range of serum LPS that we measure in experimental NEC. Antibodies against CD14 and TLR4 were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnologies (Santa Cruz, CA), against phospho-p38-MAPK and phospho-extracellular-signal related kinase (ERK) from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA), and against β-actin from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Unless otherwise specified, all other reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO).

SDS-PAGE and Immunocytochemistry

For SDS-PAGE, cell lysates were prepared by collecting cultured enterocytes (IEC-6) in cell lysis buffer (Cytoskeleton, Denver CO) or mucosal scrapings from freshly isolated murine terminal ileum were harvested in tissue lysis buffer (Cell Signaling Technologies, Beverly, MA). Protein concentration was determined using the bicinchoninic acid (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) assay. Protein lysates, 30µg per lane, were subjected to SDS-PAGE. For immunocytochemistry, enterocytes (IEC-6) were cultured and treated on glass and then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. Cells were then permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 and non-specific binding was blocked with 5% goat and 5% donkey serum. Cells were co-immunostained with anti-TLR4 (concentration=1:100) and anti-CD14 (concentration=1:100) antibodies for one hours. Secondary antibodies (anti-goat Cy5-conjugate (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA) for TLR4 and anti-mouse AlexaFlour 555 conjugate (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) for CD14) were applied at a concentration of 1:1000 for one hour. Cells were examined using an Olympus Fluoview 1000 confocal microscope, images were cropped using Adobe Photoshop (Adobe Systems Inc, San Jose, CA) and overlapping images were merged and co-localization analysis was performed using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD).

RNA Preparation and PCR

Cultured enterocytes (IEC-6) or mucosal scrapings from freshly isolated terminal ilea were collected in RNAlater (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) RNA preservation solution. RNA was extracted using RNEasy Mini kits (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). cDNA synthesis (0.5–1.0µg RNA) and genomic DNA elimination was performed using the Quantitect Reverse Transcription kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). PCR was carried out using a BioRad (Hercules, CA) MyCycler. The following primers were used: mouse CD14: sense: 5’ - CAGCCCTCTGTCCCCTCAA - 3’, mouse CD14 antisense: 5’-CATCCCGCAGTGAATTGTGA - 3’; mouse IL-6 sense: 5’-CCAATTTCCAATGCTCTCCT - 3’, mouse IL-6 antisense: 5’-ACCACAGTGAGGAATGTCCA - 3’, mouse β-actin sense: 5’-CCACAGCTGAGAGGGAAATC - 3’, mouse β-actin antisense: 5’-TCTCCAGGGAGGAAGAGGAT - 3’. PCR was performed using the following parameters: denaturation at 94°C for 30s, annealing at 56°C for 30s, and extension at 72°C for 90s. PCR was carried out for 35 cycles for all genes analyzed and PCR products were separated by electrophoresis on a 2.5% agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide. Images were captured using a Kodak (New Haven, CT) Gel Logic 100 Imaging System and Kodak (New Haven, CT) Molecular Imaging software, and band density was analyzed using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD).

In vivo induction of endotoxemia and necrotizing enterocolitis

Wild-type mice (C57Bl/6) were obtained from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). CD14−/− mice, a kind gift from Dr. Mason Freeman (Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA) were backcrossed at least 6 times and bred in our facility. All animal experiments were carried out as approved by the Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh Animal Care and Use Committee or the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Pittsburgh (Protocol 0805). Endotoxemia was induced in 2–3 week-old C57Bl/6 or CD14−/− mice by a single intraperitoneal injection of LPS (5 mg/kg). Three hours after injection, unless otherwise indicated, mice were sacrificed. Serum was collected by retro-orbital sinus puncture and terminal ilea were isolated. Terminal ilea were flushed with saline to remove luminal contents, opened longitudinally and mucosal scrapings collected. NEC was induced in 2–3 week old C57Bl/6 mice by a combination of gavage formula (2:1 Similac Advanced infant formula (Ross Pediatrics):Esbilac canine milk replacer (Pet-Ag)) feeding 5 times per day (40µl/g) and exposure to intermittent hypoxia (100% N2) for 90 seconds in a Billups-Rothenberg (Del-Mar, CA) hypoxia chamber twice daily for 4 days as previously described (19, 20). Animals were sacrificed and serum and terminal ileal mucosal scrapings collected described above.

Cytokine Analysis

For determination of enterocyte (IEC-6) cytokine release in vitro, 1×105 cells/well were seeded in 48-well plates. Cells were treated in triplicate with LPS (50 µg/ml, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), where indicated, for 6 hours. Cell culture supernatants were collected and purified by centrifugation. Supernatant IL-6 was quantified by ELISA (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). For in vivo experiments, serum IL-6 levels were determined by ELISA (R&D) Systems, Minneapolis, MN).

Statistics

Data are presented as mean +/− SEM. Statistical comparisons were made using the two-tailed Student’s t-test with an accepted statistical significance of p<0.05.

RESULTS

CD14 expression is transiently increased after LPS stimulation in IEC-6 enterocytes

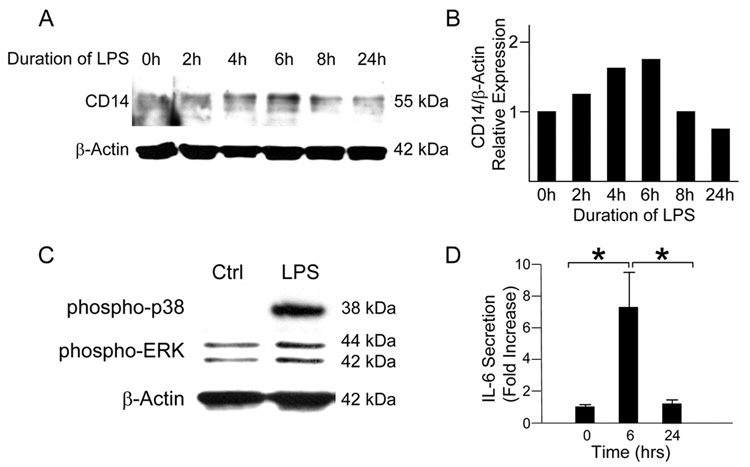

We first sought to test the hypothesis that LPS-induced inflammatory signaling would be accompanied by changes in CD14 expression in intestinal epithelial cells. To do so, we stimulated IEC-6 enterocytes with LPS (50µg/ml) and harvested cells for protein at various time-points. Western blot analysis demonstrated a stepwise increase in CD14 protein expression up to a peak at 6 hours (Figure 1A). CD14 levels returned to baseline by the 24-hour time-point. In support of a CD14-dependent effect on the pro-inflammatory signaling response, we detected early pro-inflammatory intracellular signaling events marked by a significant increase in expression of phosphorylated p38-MAPK and ERK after just 20 minutes of LPS stimulation by Western blot analysis (Figure 1B). Analysis of the media from cells stimulated with LPS demonstrated a significant increase in IL-6 at 6 hours as compared to baseline (Figure 1C). Taken together, these data suggest that LPS stimulates both increased CD14 expression and an early pro-inflammatory response in enterocytes.

Figure 1. CD14 expression exhibits a transient response to LPS stimulation in IEC-6 cells.

(A) IEC-6 cells were stimulated with LPS (50 µg/ml) for 0 to 24 hours. SDS-PAGE and band density analysis of lysates demonstrates a peak of CD14 protein at 6 hours after treatment followed by a gradual return to near baseline levels by 24 hours. (B) IEC-6 cells stimulated with LPS demonstrate an increase in phosphorylation of the MAPK p38 and ERK after 20 minutes of stimulation. (C) Analysis of the media of LPS-stimulated IEC-6 cells by ELISA demonstrates a significant increase in IL-6 levels at 6 hours after stimulation (1.0 +/− 0.1 vs. 7.1 +/− 2.6 fold increase, *p<0.05). IL-6 levels return to baseline by 24 hours (7.1 +/− 2.6 vs. 1.2 +/− 0.2 fold increase, *p<0.05).

CD14 is internalized along with TLR4 in IEC-6 cells stimulated with LPS

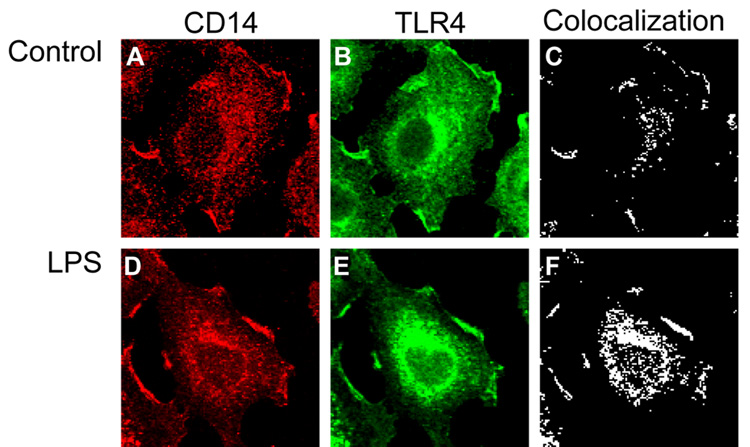

It has been demonstrated with TLR4 is internalized in an intestinal epithelial cell line upon stimulation with LPS (21). Since CD14 is known to interact closely with TLR4 upon stimulation with LPS, we hypothesized that CD14 may be internalized along with TLR4 in enterocytes exposed to LPS. In order to demonstrate this, IEC-6 cells were co-immunostained for CD14 and TLR4. In untreated cells, CD14 was found to colocalize at basal levels with TLR4 at the cell surface and in intracellular compartments (Figure 2A–C). Upon stimulation with LPS and co-immunostaining for CD14 and TLR4, a significant increase in colocalization of CD14 and TLR4 in an intracellular compartment was observed (Figure 2D–F).

Figure 2. CD14 is internalized along with TLR4 in IEC-6 cells stimulated with LPS.

IEC-6 cells were stimulated with media alone or LPS (50 µg/ml) for 1 hour and prepared for confocal immunofluorescence microscopy. A–C: Untreated cells; D–F – LPS-treated cells. Shown are the expression of CD14 (panels A, D), TLR4 (B, E) or colcoalization (C, F), as calculated using ImageJ software.

Endotoxemia stimulates an early CD14-dependent inflammatory response in mice

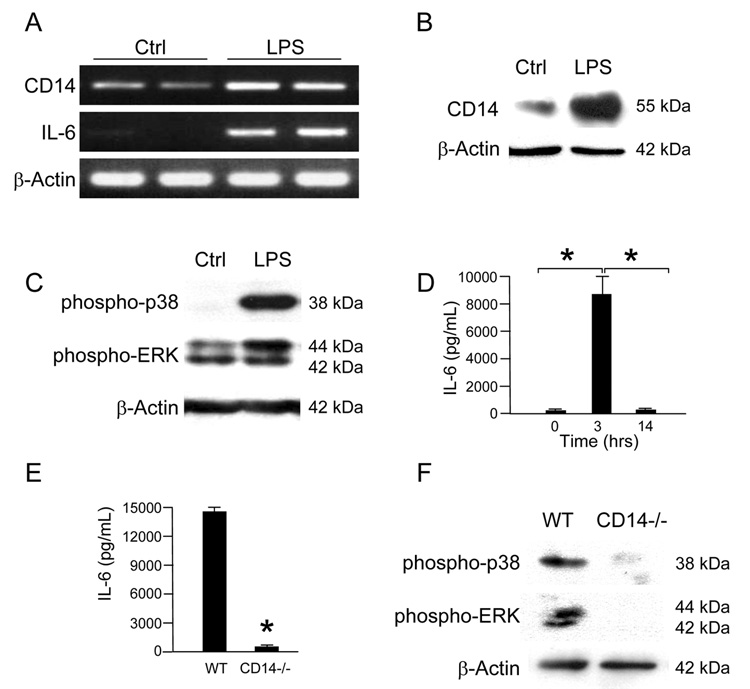

Based upon these in vitro studies, we next hypothesized that CD14 expression would be increased in the intestinal mucosa of mice subjected to acute experimental endotoxemia, which may parallel the situation observed in early NEC. To test this, C57Bl/6 mice were injected intraperitoneally with LPS (5mg/kg) and sacrificed at 3 hours. A significant increase in CD14 mRNA expression as compared to untreated mice was noted in the ileal mucosa, and mirrored ileal mucosal IL-6 expression (Figure 3A). These findings were also associated with increased levels of CD14 protein expression compared to untreated mice (Figure 3B). Further demonstrating pro-inflammatory signaling, the intestinal mucosa obtained from WT mice subjected to endotoxemia at 3 hours demonstrated increased phosphorylation of both p38-MAPK and ERK (Figure 3C). A significant increase in systemic IL-6 release as measured by serum ELISA was noted in mice exposed to endotoxin as compared to controls at 3 hours, which was then found to decrease to baseline by 14 hours consistent with the in vitro findings (Figure 3D). Although wild-type mice exhibited a robust IL-6 response and activation of MAPK phosphorlylation to LPS at 3 hours, CD14−/− mice failed to do so (Figure 3E,F). These data suggest that the inflammatory response to LPS in vivo both at the tissue level and in the systemic circulation is highly dependent on CD14, and that an early increase in CD14 expression may potentiate this inflammatory response.

Figure 3. Endotoxemia stimulates an early CD14-dependent inflammatory response in mice.

(A) C57Bl/6 mice were injected with LPS (5mg/kg) and sacrificed at 3 hours. RT-PCR analysis of ileal mucosa mRNA demonstrates increased expression of CD14 and IL-6 as compared to control mice. (B) SDS-PAGE of ileal mucosa from WT mice exposed to LPS for 3 hours similarly demonstrates increased CD14 expression as compared to saline-treated mice. (C) SDS-PAGE of ileal mucosa from WT mice exposed to LPS for 3 hours demonstrates increased phosphorylation of p38 and ERK as compared to saline-treated mice. (D) C57Bl/6 mice were sacrificed at 0, 3 and 14 hours after injection with LPS. Analysis of serum IL-6 by ELISA demonstrates a significant increase in levels from 0 to 3 hours (5.5 +/− 4.5 vs. 8656 +/− 1541.6, *p<0.05) followed by a significant return to baseline by 14 hours (8656 +/− 1541.6 vs. 27.6 +/− 18.2, *p<0.05). (E) C57Bl/6 mice and CD14−/− mice were sacrificed at 3 hours after injection with LPS. CD14−/− mice demonstrated a significant decrease in IL-6 levels as compared to WT mice (14445.5 +/− 137.6 vs. 568.6 +/− 83.5, *p<0.05). (F) The phosphorylation of MAPK in the ileal mucosa of CD14−/− mice compared to WT mice sacrificed 3 hours after injection with LPS is markedly decreased.

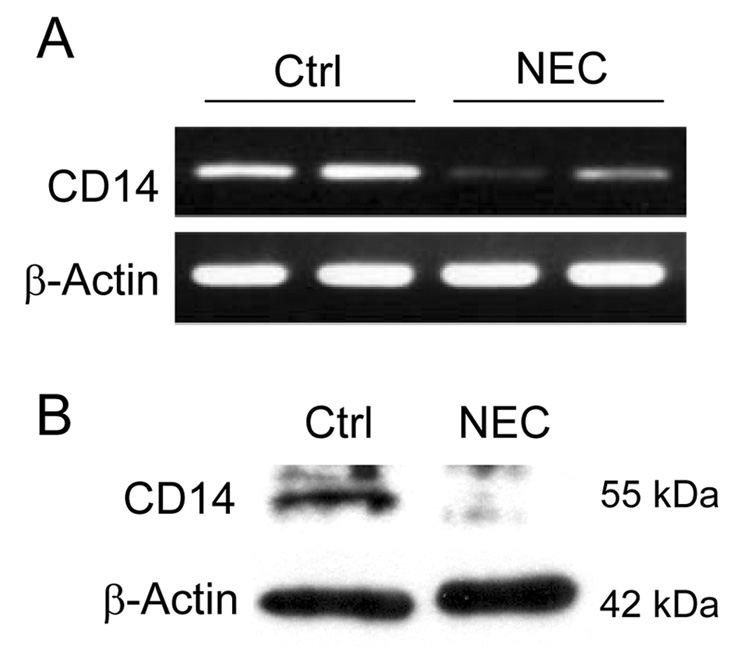

Having shown the importance of a transient increase in CD14 expression in enterocytes in mediating LPS signaling in vitro and in vivo, we next hypothesized that CD14 expression within the intestinal mucosa would follow a similar pattern in mice subjected to a model of experimental NEC, with a prolonged decrease in expression after the development of NEC. To test this hypothesis, C57Bl/6 mice were subjected to a model of experimental NEC. As shown in Figure 4 A, B, at 4 days, mice were sacrificed and ileal mucosa was harvested for both protein and RNA analysis. Notably, CD14 mRNA and protein levels were found to be significantly decreased in the ilea of mice subjected to a 4-day experimental NEC model. Taken together, the current data suggest a potential role for a transient increase in CD14 expression and signaling in the initiating events in the development of NEC.

Figure 4. The transient response of CD14 expression to LPS is implicated in the development of necrotizing enterocolitis.

C57Bl/6 mice were subjected to an experimental model of NEC and sacrificed at 5 days. (A) Semi-quantitative RT-PCR analysis of ileal mucosa mRNA and (B) western blot analysis of ileal mucosal scrapings demonstrate decreased expression of CD14 as compared to control mice.

DISCUSSION

In the current study, we show that LPS stimulates a potent inflammatory response in enterocytes both in vitro and in vivo. The acute phase of this response characterized by MAPK phosphorylation and subsequent IL-6 release both locally and systemically, is transient in nature with a return to baseline within the first day of exposure. Expression of the TLR4 co-receptor CD14 mirrors this acute response. Further, CD14 is internalized along with TLR4 upon exposure to LPS in vitro. After prolonged exposure to LPS, as was observed in a model of chronic murine endotoxemia in experimental NEC, the expression of CD14 within the intestinal mucosa is decreased. Given recent findings from our laboratory and the Caplan laboratory demonstrating the importance of LPS-mediated signaling in the pathogenesis of NEC (9, 10), we now propose a novel role for CD14 in the regulation of LPS signaling, potentially contributing to the initiating events in the development of NEC.

How may CD14 participate in the pathogenesis of NEC? TLR4 was originally described as a receptor for LPS. However, a variety of studies suggest that no direct binding occurs between these two molecules (7, 12, 22–24). LPS must rely on co-receptors such as LBP, MD2 and CD14 to activate the transmembrane TLR4 receptor and initiate signaling. LPS is first bound to soluble LBP and then transferred to CD14 (25–27), which then acts to shuttle LPS to the TLR4-bound MD2. This direct interaction between MD2 and LPS serves to activate TLR4 and stimulate intracellular signaling. We now propose that an early activation of TLR4 by CD14 initiates the signaling cascade that is required for the development of NEC. Our current finding that TLR4 and CD14 co-localize and are co-internalized upon LPS exposure underscore this possibility. The subsequent decrease in CD14 expression and signaling may represent a state of acquired endotoxin tolerance, as has recently been described to occur in other systems (28, 29).

It is important to point out several important caveats with regard to the current study. First, CD14 levels were only evaluated during experimental NEC after the establishment of the disease by day 4 and not earlier, as it is not possible to know which animals will go on to develop the disease and which will not. As such, we have used murine endotoxemia as a surrogate of early NEC, realizing there may be important differences between these two conditions, even at early stages. Second, we have not currently examined whether CD14 knockout mice are protected from the development of NEC. However, based upon our recent finding that TLR4 mutant mice are protected from the development of NEC, one would expect CD14 knockout mice to be similarly protected. Despite these reservations, we feel that the current analysis provides important information regarding the potential role[s] of CD14 in the early signaling events that may be observed during the subsequent development of experimental NEC.

In summary, the current data provide evidence that CD14 may play a role in the pathogenesis of NEC through effects on LPS-mediated signaling in enterocytes. Taken in aggregate, these findings provide a rationale for CD14-mediated therapies, as has been studied in sepsis (30, 31), in the management of this disorder.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by R01 GM078238-01 (D.J.H), the American College of Surgeons Resident Research Scholarships (K.P.M., S.C.G., D.J.K.), the Surgical Infection Society Resident Research Award (R.J.A.), and the Loan Repayment Award from the National Institutes of Health (S.C.G.).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lambert DK, Christensen RD, Henry E, et al. Necrotizing enterocolitis in term neonates: data from a multihospital health-care system. J Perinatol. 2007 doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7211738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lin PW, Stoll BJ. Necrotising enterocolitis. Lancet. 2006;368:1271–1283. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69525-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Warner BW, Warner BB. Role of epidermal growth factor in the pathogenesis of neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2005;14:175–180. doi: 10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2005.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hsueh W, Caplan MS, Qu XW, et al. Neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis: clinical considerations and pathogenetic concepts. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2003;6:6–23. doi: 10.1007/s10024-002-0602-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anand R, Leaphart CL, Mollen K, et al. The Role of the Intestinal Barrier in the Pathogenesis of Necrotizing Enterocolitis. Shock. 2007;27:124–133. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000239774.02904.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sharma R, Tepas JJ, Hudak ML, et al. Neonatal gut barrier and multiple organ failure: role of endotoxin and proinflammatory cytokines in sepsis and necrotizing enterocolitis. J Pediatr Surg. 2007;42:454–461. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2006.10.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Poltorak A, He X, Smirnova I, Liu MY, et al. Defective LPS signaling in C3H/HeJ and C57BL/10ScCr mice: mutations in Tlr4 gene. Science. 1998;282:2085–2088. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5396.2085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Qureshi ST, Gros P, Malo D. The Lps locus: genetic regulation of host responses to bacterial lipopolysaccharide. Inflamm Res. 1999;48:613–620. doi: 10.1007/s000110050511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leaphart CL, Cavallo J, Gribar SC, et al. A Critical Role for TLR4 in the Pathogenesis of Necrotizing Enterocolitis by Modulating Intestinal Injury and Repair. J Immunol. 2007;179:4808–4820. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.7.4808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jilling T, Simon D, Lu J, et al. The roles of bacteria and TLR4 in rat and murine models of necrotizing enterocolitis. J Immunol. 2006;177:3273–3282. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.5.3273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Akira S, Sato S. Toll-like receptors and their signaling mechanisms. Scandinavian journal of infectious diseases. 2003;35:555–562. doi: 10.1080/00365540310015683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miller SI, Ernst RK, Bader MW. LPS, TLR4 and infectious disease diversity. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2005;3:36–46. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dauphinee SM, Karsan A. Lipopolysaccharide signaling in endothelial cells. Laboratory investigation; a journal of technical methods and pathology. 2006;86:9–22. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gangloff SC, Zahringer U, Blondin C, et al. Influence of CD14 on ligand interactions between lipopolysaccharide and its receptor complex. J Immunol. 2005;175:3940–3945. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.6.3940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haziot A, Hijiya N, Schultz K, et al. CD14 plays no major role in shock induced by Staphylococcus aureus but down-regulates TNF-alpha production. J Immunol. 1999;162:4801–4805. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Triantafilou M, Triantafilou K, Fernandez N. Rough and smooth forms of fluorescein-labelled bacterial endotoxin exhibit CD14/LBP dependent and independent binding that is influencedby endotoxin concentration. European journal of biochemistry / FEBS. 2000;267:2218–2226. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01222.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Quaroni A, Wands J, Trelstad RL, et al. Epithelioid cell cultures from rat small intestine. Characterization by morphologic and immunologic criteria. J Cell Biol. 1979;80:248–265. doi: 10.1083/jcb.80.2.248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mann EA, Cohen MB, Giannella RA. Comparison of receptors for Escherichia coli heat-stable enterotoxin: novel receptor present in IEC-6 cells. Am J Physiol. 1993;264:G172–G178. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1993.264.1.G172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nadler EP, Dickinson E, Knisely A, et al. Expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase and interleukin-12 in experimental necrotizing enterocolitis. J Surg Res. 2000;92:71–77. doi: 10.1006/jsre.2000.5877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leaphart CL, Qureshi F, Cetin S, et al. J. Interferon-[gamma] Inhibits Intestinal Restitution by Preventing Gap Junction Communication Between Enterocytes. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:2395–2411. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hornef MW, Frisan T, Vandewalle A, et al. Toll-like receptor 4 resides in the Golgi apparatus and colocalizes with internalized lipopolysaccharide in intestinal epithelial cells. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2002;195:559–570. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fitzgerald KA, Rowe DC, Golenbock DT. Endotoxin recognition and signal transduction by the TLR4/MD2-complex. Microbes and Infection. 2004;6:1361–1367. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2004.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guha M, Mackman N. LPS induction of gene expression in human monocytes. Cellular Signalling. 2001;13:85–94. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(00)00149-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Visintin A, Mazzoni A, Spitzer JH, et al. Regulation of Toll-like receptors in human monocytes and dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2001;166:249–255. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.1.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kobayashi M, Saitoh S, Tanimura N, et al. Regulatory roles for MD-2 and TLR4 in ligand-induced receptor clustering. J Immunol. 2006;176:6211–6218. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.10.6211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim JI, Lee CJ, Jin MS, et al. Crystal structure of CD14 and its implications for lipopolysaccharide signaling. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2005;280:11347–11351. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M414607200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Visintin A, Iliev DB, Monks BG, et al. Md-2. Immunobiology. 2006;211:437–444. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2006.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lin SM, Frevert CW, Kajikawa O, et al. Differential regulation of membrane CD14 expression and endotoxin-tolerance in alveolar macrophages. American journal of respiratory cell and molecular biology. 2004;31:162–170. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2003-0307OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fan H, Cook JA. Molecular mechanisms of endotoxin tolerance. Journal of endotoxin research. 2004;12 doi: 10.1179/096805104225003997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Verbon A, Meijers JC, Spek CA, et al. Effects of IC14, an anti-CD14 antibody, on coagulation and fibrinolysis during low-grade endotoxemia in humans. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2003;187:55–61. doi: 10.1086/346043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reinhart K, Gluck T, Ligtenberg J, et al. CD14 receptor occupancy in severe sepsis: results of a phase I clinical trial with a recombinant chimeric CD14 monoclonal antibody (IC14) Critical care medicine. 2004;32:1100–1108. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000124870.42312.c4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]