Abstract

Determination of the genetic factors that control the progression of left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) to heart failure has been difficult despite extensive study in animal models. Here we have characterized a consomic rat model of LVH resulting from the introgression of chromosome 16 from the normotensive Brown Norway (BN) rat onto the genetic background of the Dahl salt-sensitive (SS/Mcwi) rat by marker assisted breeding. The SS-16BN/Mcwi consomic rats are normotensive but display LVH equivalent to the hypertensive SS/Mcwi rats at early ages. In this study we tracked the development of LVH by echocardiography and analyzed changes in cardiac function and morphology with aging in the SS-16BN/Mcwi, SS/Mcwi, and BN to determine if the consomic SS-16BN/Mcwi was a model of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM). Aging SS-16BN/Mcwi rats showed no evidence of heart failure or impaired cardiac function upon extensive analysis of left ventricle function by echocardiography and pressure-volume relationships, while their parental SS/Mcwi experienced deterioration in function between 18 and 36 wk of age. In addition aging SS-16BN/Mcwi did not exhibit tissue remodeling common to pathological hypertrophy and HCM such as increased fibrosis and reduced capillary density in the myocardium. In fact, SS-16BN/Mcwi were better protected from developing LV fibrosis with age than either the hypertensive SS/Mcwi or normotensive BN parental strains. This suggests that a gene or genes on chromosome 16 may be involved with both blood pressure regulation and preservation of cardiac function with aging.

Keywords: left ventricular hypertrophy, hypertension, heart failure, capillary density, fibrosis

pathological left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) is a very strong predictor of cardiovascular events and heart failure (21). Despite extensive study, the mechanisms underlying the development of cardiac hypertrophy and loss of function remain largely unknown.

Genetically modified animal models have provided important information implicating a variety of pathways in left ventricular dysfunction and heart failure. As part of a large effort to identify the genetic basis of cardiovascular disease, the National Institutes of Health Programs for Genomic Applications (PGA), Physgen, identified a unique rat strain that appeared to undergo significant progressive LVH in the absence of hypertension (17). This strain, referred to as the SS-16BN/Mcwi, is a consomic rat in which chromosome 16 of the Brown Norway (BN) rat is introduced onto the salt-sensitive Dahl (SS/Mcwi) genetic background by marker assisted breeding (13). The BN rat is normotensive and does not exhibit any signs of inappropriate LVH. Conversely, the SS/Mcwi rat is a model for LVH induced by systemic hypertension that eventually progresses to heart failure (18, 20, 22).

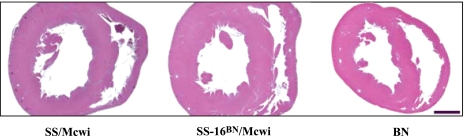

In the PGA extensive phenotypic analysis was completed on all consomic strains (17). This screening determined that BN chromosome 16 was able to protect the consomic SS-16BN/Mcwi from developing hypertension on either a 3 wk high (4.0%) or low (0.4%) salt diet [mean arterial pressure (MAP): 129.5 and 120.1 mmHg, respectively] at 11 wk of age. Histological sections from 9 wk old animals revealed that the left ventricular wall thickness of the SS-16BN/Mcwi rat was greater than the SS/Mcwi or the BN, indicating LVH (Fig. 1). These preliminary data suggested that the SS-16BN/Mcwi may be a model of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM).

Fig. 1.

Left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) phenotype in SS-16BN/Mcwi. Trichrome-stained midventricle sections from 9 wk old male rats exhibit LVH in the SS-16BN/Mcwi compared with the parental SS/Mcwi rat. Images were taken directly from the Programs for Genomic Applications (PGA) website. Bar represents 2 mm.

Our goals for the current study were twofold. First, we wanted to determine if the SS-16BN/Mcwi is a model of HCM. Secondly, we wanted to examine if any impairment in cardiac function accompanied the hypertrophy. To accomplish this SS-16BN/Mcwi, SS/Mcwi, and BN rats were extensively characterized for both morphological and functional cardiovascular phenotypes and compared as they aged from 18 to 36 wk of age on a normal (1%) salt diet. The results of this characterization showed that the SS-16BN/Mcwi rat developed early LVH despite a normotensive blood pressure. In addition SS-16BN/Mcwi rats were better protected from developing the age related phenotype of left ventricular fibrosis than either hypertensive SS/Mcwi or normotensive BN parental rats. These results implicate genes on chromosome 16 in regulation of blood pressure and cardiovascular function with aging.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Male SS/Mcwi (n = 53), SS-16BN/Mcwi (n = 54), and BN/Mcwi (n = 37) rats were obtained from colonies at the Medical College of Wisconsin (MCW) and housed in the MCW Biomedical Resource Center on a 12:12 h light-dark cycle. They were given a standard rat chow (Purina) containing 1% salt and water ad libitum.

All animal protocols were approved by the MCW Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. For all procedures rats were anesthetized by an intramuscular injection of ketamine (100 mg/kg), xylazine (50 mg/kg), and acepromazine (2 mg/kg).

Echocardiography

Transthoracic echocardiography (Vivid 7, GE) was performed on anesthetized rats weekly between 7 and 18 wk of age and again at 36 wk of age. Short axis views of left ventricles were acquired midpapillary. Wall thickness was measured from the M-mode view. Fractional shortening was calculated from measurements of the chamber diameter {%FS = [(dLVID − sLVID)/dLVID]*100}.

Stress Tests

Stress tests were completed on anesthetized rats by jugular vein infusion of 40 μg·kg−1·min−1 dobutamine. MAP was measured by catheterization of the carotid artery. Echocardiography and MAP recordings were made at baseline (before dobutamine infusion) and between 4 min and 4 min 30 s of dobutamine infusion. Left ventricle dimensions and function were determined by echocardiography as described above.

Pressure Volume Loops

Left ventricle pressure-volume loops were recorded using a MPVS-400 System (Millar Pressure-Volume Systems; Millar Instruments, Houston, TX). The catheter was inserted through the right carotid artery and advanced retrograde into the left ventricle. Following each experiment the pressure and volume signals were carefully calibrated as suggested by Millar (24) and others (5, 16) to correct for hematocrit and parallel conductance. Software in the Millar system was used to generate PV loops and calculate reported values, such as ejection fraction (EF) and cardiac index (CI) from the raw data. End-systolic elastance (Ees) was calculated from the end-systolic pressure-volume relationship during abdominal aortic occlusion.

Tissue Collection and Histology

Following the functional measurements the heart was excised rapidly and placed in 500 mM KCl for morphological analysis. The wet weight of excised hearts was determined. Atria were removed, and the wet weight of the ventricles was taken. The ventricles were then cut in cross section midventricle. The apex portion was fixed in 10% formalin for trichrome staining, and the base portion was mounted in cutting medium for immunohistochemistry to facilitate capillary and myocyte visualization.

Fibrotic Tissue in the LV

The formalin fixed apex of the heart was mounted in wax, sliced, and rehydrated before trichrome staining was performed. Images of the slide mounted sections were visualized with a Nikon E-400 microscope and (Nikon Instruments, Melville, NY) and acquired using a SPOT Insight digital camera (Diagnostic Instruments, Sterling Heights, MI). Fibrotic tissue was quantified as percent of LV tissue using Metamorph software (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA).

Capillary-to-fiber Ratios

The mounted and frozen base of the ventricles was cut in 5 mm thick cross sections in the midventricle region using a Microm HM 550 cryostat (Walldorf, Germany). Sections were dried overnight before being rehydrated in Tris-buffered saline (TBS). Endogenous peroxidases were blocked by 2 min incubation with 1.5% hydrogen peroxide diluted in methanol. Nonspecific binding of antibodies was reduced by incubation in 1% horse and 1% goat serum for 1 h before antibodies were applied. In addition all antibodies were diluted in 3% horse serum in TBS. To visualize capillaries an anti-CD31 (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA) primary antibody (1:100) was applied for 1 h followed by 1 h incubation with biotinylated anti-mouse (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) secondary antibody (1:100). DAB (Vector Laboratories) was applied for 4 min to stain the CD-31 antibody-bound capillaries. To visualize the myocyte borders an anti-caveolin-3 (Abcam, Cambridge, MA) primary antibody (1:100) was applied for 1 h, followed by biotinylated anti-rabbit (Vector Laboratories) secondary antibody (1:100). Nova red (Vector Laboratories) was used to visualize the caveolin-3 antibodies bound to myocyte borders.

Myocardium in the interventricular septum, dorsal wall, ventral wall and outer wall were photographed at a ×40 magnification. Fields selected for these photos were those in which the fibers and capillaries had been cut in cross section (32). Metamorph software (Molecular Devices) was then used to measure the area of all fibers in the field that were clearly defined. Capillaries with an area of <200 μm2 were not included in average area. The number of capillaries contacting each one of these fibers was then counted. The average number of capillaries per fiber and the average number of capillaries per square micron were calculated.

Data Analysis

Results were expressed as means ± SE. Two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to evaluate all data for differences betweens strain and age. For data taken at only one time point one-way ANOVA was utilized. For end systolic and diastolic volumes and pressures measured by the MPVS-400 system a Mann-Whitney rank sum test was performed to compare 18 and 36 wk values. Ees was analyzed using Dunn's one-way ANOVA. With all statistical analysis differences between groups and/or ages were considered statistically significant when P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Verification of Hypertrophy

Wall thickness measurement by echocardiography.

To determine the time course and severity of the hypertrophy in the SS-16BN/Mcwi rat, ultrasound measurements of LV wall thickness were performed as rats aged from 7 to 36 wk of age. Between 18 and 36 wk of age 38% of the SS/Mcwi became moribund and died or had to be euthanized. No deaths were observed in the SS-16BN/Mcwi and BN rats.

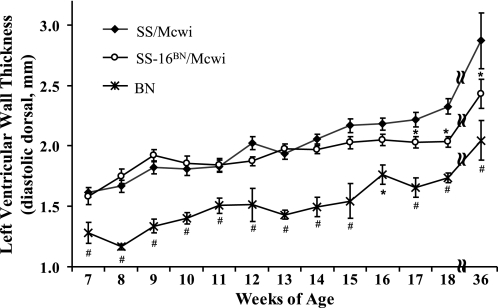

The diastolic ventral wall thickness was slightly higher in the SS-16BN/Mcwi compared with the SS/Mcwi rats between 8 and 10 wk of age, supporting PGA findings (Fig. 2). However, wall thickness in the SS-16BN/Mcwi remained relatively constant between 9 and 18 wk of age. SS/Mcwi and SS-16BN/Mcwi rats had significantly thicker LV walls at nearly every time point compared with BN. At 17 wk SS/Mcwi and SS-16BN/Mcwi diverged with SS/Mcwi diastolic wall thickness exceeding of the SS-16BN/Mcwi.

Fig. 2.

Left ventricular wall thickness measured over time. Diastolic dorsal LV wall thickness (dDLVWT) was measured by transthoracic echocardiography in SS/Mcwi (n = 41), SS-16BN/Mcwi (n = 41), and BN (n = 21) rats between 7 and 36 wk of age. Each time point represents 5–28 SS/Mcwi, 5–26 SS-16BN/Mcwi, and 3–14 BN rats. Results represent means ± SE. *P <0.05 vs. SS/Mcwi, #P < 0.05 vs. SS/Mcwi and SS-16BN/Mcwi (ANOVA).

Ventricle weight as portion of body weight.

The wet weight of the right and left ventricle was normalized to body weight to verify ultrasound results and account for any differences in cardiac mass due to animal size (Table 1). The SS/Mcwi rats experienced a large increase in body weight normalized ventricle weight between 18 and 36 wk of age indicating LVH excessive to that which can be attributed to normal body growth. There was no difference in either the SS-16BN/Mcwi or the BN rats during this time period. At 18 and 36 wk of age the normalized ventricle weights were significantly different in all three strains, with the SS-16BN/Mcwi being intermediate. Values for ventricle weight and body weight are listed in Table 1. The body weights of the SS/Mcwi and SS-16BN/Mcwi rats are not different at 36 wk of age, indicating that the higher normalized ventricle weight in the SS/Mcwi is due to increased LV mass rather than reduced body weight with aging.

Table 1.

Effects of aging on body and ventricle weight

| Age, wk |

SS/Mcwi |

SS-16BN/Mcwi

|

BN

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18 | 36 | 18 | 36 | 18 | 36 | |

| Body weight, g | 394±8‡ | 431±24†‡ | 398±6‡ | 450±6†‡ | 300±7 | 338±11† |

| R and L ventricle weight, g | 1.35±0.06‡ | 1.97±0.14†‡ | 1.22±0.03‡ | 1.46±0.05†‡ | 0.78±0.02* | 1.00±0.02*† |

| Normalized ventricle weight, g/kg | 3.44±0.13‡ | 4.62±0.38†‡ | 3.07±0.50*‡ | 3.25±0.13*‡ | 2.60±0.07* | 2.65±0.08* |

Body weight and ventricle weights (right and left) measured in SS/Mcwi (n = 20 at 18 wk, n = 5 at 36 wk), SS-16BN/Mcwi (n = 21 at 18 wk, n = 5 at 36 wk), and BN/Mcwi (n = 6 at 18 wk, n = 5 at 36 wk). Results represent means ± SE.

P < 0.05 vs. BN at same age;

P < 0.05 vs. SS/Mcwi at same age;

P < 0.05 vs. 18 wk within strain (ANOVA).

Blood Pressure

Systolic and diastolic blood pressure.

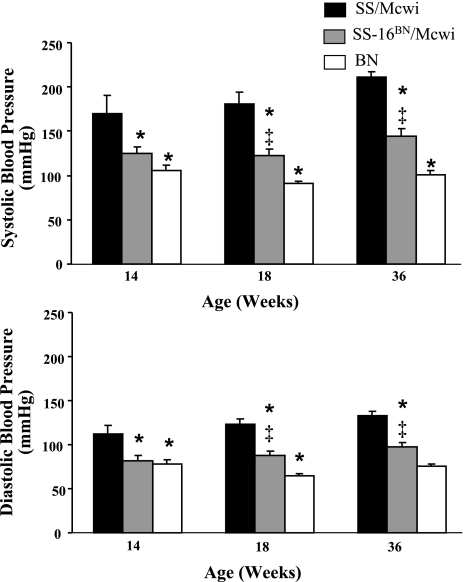

At 14, 18, and 36 wk of age the SS/Mcwi rats had significantly higher systolic and diastolic blood pressures than the SS-16BN/Mcwi or BN rats (Fig. 3). The SS-16BN/Mcwi rats also had higher systolic (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) than the BN rats at 18 and 36 wk of age. Blood pressure did not increase significantly in any of the strains between any of the time points.

Fig. 3.

Systolic and diastolic blood pressure with aging. Measurements were made with the MPVS. SS/Mcwi (n = 6 at 14 wk, n = 10 at 18 wk n = 6 at 36 wk), SS-16BN/Mcwi (n = 8 at 14 wk, n = 8 at 14 wk, and n = 8 at 36 wk), and BN (n = 7 at 14 wk, n = 7 at 18 wk, n = 9 at 36 wk). Results represent means ± SE. *P < 0.05 vs. SS/Mcwi at same age; ‡P < 0.05 vs. BN at same age (ANOVA).

Cardiac Function

Cardiac function measured by echocardiography.

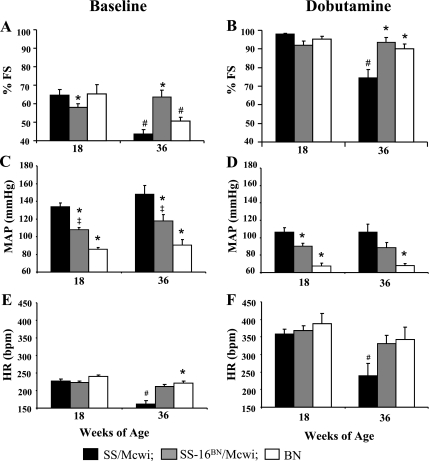

Baseline percent fractional shortening (%FS) in the three groups averaged 61.8% ± 1.5 at 18 wk with SS-16BN/Mcwi having a slight, but significantly lower %FS than SS/Mcwi or BN rats (Fig. 4A). By 36 wk of age, %FS had decreased dramatically in both the SS/Mcwi and BN rats but was preserved in the SS-16BN/Mcwi. Fractional shortening in the SS-16BN/Mcwi was significantly higher than that of the SS/Mcwi and elevated compared with that of the BN rats (P < 0.09).

Fig. 4.

Cardiac functional response to dobutamine stress with aging. Fractional shortening (%FS), mean arterial pressure (MAP), and heart rate (HR) at 18 and 36 wk of age at baseline (A, C, and E, respectively) and after 4 min of dobutamine infusion (B, D, and F, respectively). SS/Mcwi (n = 21 at 18 wk, n = 5 at 36 wk), SS-16BN/Mcwi (n = 25 at 18 wk, n = 5 at 36 wk), and BN/Mcwi (n = 5 at 18 wk, n = 5 at 36 wk). Results represent means ± SE. *P < 0.05 vs. SS/Mcwi at same age; ‡P < 0.05 vs. BN at same age; #P < 0.05 vs. 18 wk value within strain (ANOVA).

When 40 μg·kg−1·min−1 of the β-adrenergic agonist dobutamine was administered intravenously for 4 min %FS increased in all groups (Fig. 4, A and B). No difference in the %FS response was observed in any of the strains at 18 wk of age (Fig. 4B). At 36 wk of age the SS/Mcwi rats had significantly impaired ability to increase %FS compared with the SS-16BN/Mcwi and BN rats. The %FS response to dobutamine was also attenuated between 18 and 36 wk of age in the SS/Mcwi strain.

MAP was measured at baseline and during the dobutamine stress test as a measure of afterload on the heart. At baseline the MAP in the SS/Mcwi was significantly higher than in the SS-16BN/Mcwi or BN rats (Fig. 4C). The SS-16BN/Mcwi MAP was also had higher than that of the BN at both time points. Baseline MAP did not change between 18 and 36 wk in any strain.

After 4 min of 40 μg·kg−1·min−1 dobutamine infusion MAP dropped dramatically in all three rat strains (Fig. 4D). The differences between the MAPs in the three strains were diminished in the presence of dobutamine at both ages. Aging did not impair the ability of dobutamine to reduce blood pressure in any of the strains.

Heart rate (HR)was also measured at baseline (Fig. 4E) and after 4 min of dobutamine infusion (Fig. 4F). In 18 wk old animals measured at baseline no difference in HR was detected. Between 18 and 36 wk baseline HR dropped dramatically in the SS/Mcwi while remaining unchanged in the SS-16BN/Mcwi and BN. Dobutamine caused a similar elevation in HR all three strains of rats at 18 wk of age, but by 36 wk the SS/Mcwi HR response to dobutamine was significantly impaired suggesting a defect in β-adrenergic signaling consistent with heart failure.

Cardiac function measured by pressure-volume loops.

As another measure of systolic function, baseline EF measurements were made with the MPVS. The results were similar to those of baseline %FS measured by echocardiography. We found that EF was similar in the SS/Mcwi and BN at 18 wk of age and slightly reduced in the SS-16BN/Mcwi compared with the BN. By 36 wk of age SS/Mcwi EF dropped while it was enhanced in the SS-16BN/Mcwi and maintained in the BN rats (Fig. 5A).

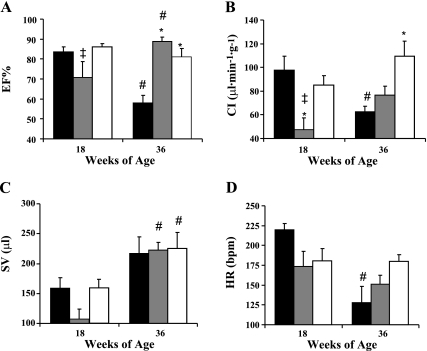

Fig. 5.

Cardiac function with aging. Ejection fraction (EF%) (A), cardiac index (CI) (B), stroke volume (SV) (C), and heart rate (HR) (D) measured by Millar PVAN. PVAN measurements made in SS/Mcwi (n = 8 at 18 wk, n = 4 at 36 wk), SS-16BN/Mcwi (n = 7 at 18 wk, n = 6 at 36 wk), and BN (n = 8 at 18 wk, n = 8 at 36 wk). Results represent mean ± SE. *P < 0.05 vs. SS/Mcwi at same age; ‡P < 0.05 vs. BN at same age; #P <0.05 vs. 18 wk value within strain (ANOVA).

CI was lower in the SS-16BN/Mcwi rats than either SS/Mcwi (P <0.05) or BN (P = 0.13) at 18 wk of age. Between 18 and 36 wk CI was unchanged in the SS-16BN/Mcwi and augmented in the BN (P = 0.11). The SS/Mcwi rats saw a large drop in CI during this time period suggesting that they may be transitioning to heart failure (Fig. 5B).

Stroke volume (SV) (Fig. 5C) and HR (Fig. 5D) were used to calculated CI. SV was lower in 18 wk old SS-16BN/Mcwi than the two parental strains though this was not statistically significant. This is the primary reason that CI is so low in the consomic animals at this age. At 36 wk of age there is no difference in SV between the three strains, with the SS-16BN/Mcwi and BN rats showing a significant increase from 18 wk of age. This was primarily the result of significantly increased end-diastolic volume with age. A significantly reduced HR between 18 and 36 wk of age in the SS/Mcwi contributed to a significantly reduced CI during this time period.

Cardiac changes to structure and function determined by pressure-volume loops.

None of the strains exhibited changes in end-systolic pressure between 18 and 36 wk of age. In the SS/Mcwi (Fig. 6A) the entire pressure-volume loop was dramatically shifted to the right. The 36 wk end-systolic LV volume (ESLVV) more than doubled the 18 wk volume, suggesting systolic dysfunction and dilated heart failure may be occurring. The BN rats (Fig. 6C) also experienced a significant increase in the ESLVV, though the rightward shift of the loop was minimal compared with the SS/Mcwi. The SS-16BN/Mcwi (Fig. 6B) exhibited no increase in ESLVV, suggesting absence of LV systolic dysfunction at 36 wk of age.

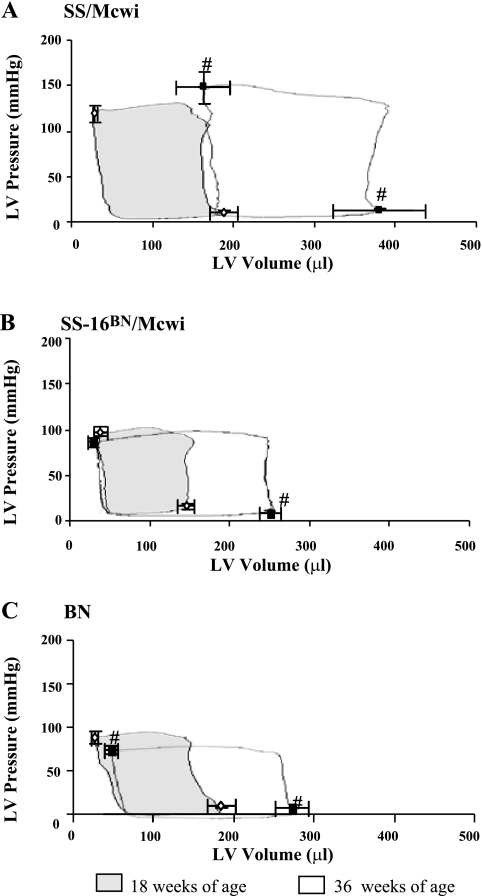

Fig. 6.

Pressure-volume loops at 18 and 36 wk of age. Representative pressure volume loops for SS/Mcwi (A), SS-16BN/Mcwi (B), and BN (C) were superimposed on 18 (◊) and 36 (▪) wk averaged end-systolic and end-diastolic pressures/volumes. 18 wk loops are shaded. PVAN measurements made in SS/Mcwi (n = 8 at 18 wk, n = 4 at 36 wk), SS-16BN/Mcwi (n = 7 at 18 wk, n = 6 at 36 wk), and BN/Mcwi (n = 8 at 18 wk, n = 8 at 36 wk). Results represent means ± SE. #P <0.05 vs. 18 wk volume within strain (Mann-Whitney rank sum test).

The Ees of the LV was also measured in 36 wk old rats during abdominal aortic occlusion. Ees is the slope of the end-systolic pressure volume relationship, and it represents the stiffness of the LV at end-systole. A higher Ees indicates better systolic function of the LV. Despite the large increase in ESLVV the Ees in SS/Mcwi rats (n = 4, 0.78 ± 0.11 mmHg/ml) was not statistically different from SS-16BN/Mcwi rats (n = 5, Ees = 0.40 ± 0.09 mmHg/ml). The aged SS/Mcwi rats were able preserve systolic function by increasing end-systolic stiffness even though they showed systolic dilation. In contrast, the Ees of BN (n = 7, 0.23 ± 0.02 mmHg/ml) rats was significantly lower than that of SS-16BN/Mcwi rats.

LV Histology

Capillary and fiber distribution.

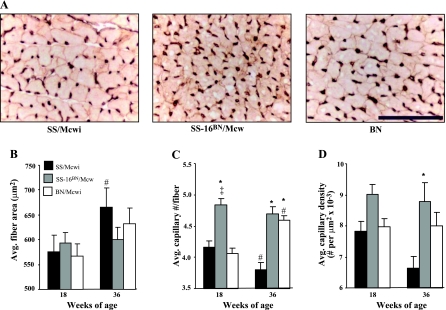

Inspection of sections of stained LV myocardium suggested an increase capillary density in the myocardium of the SS-16BN/Mcwi rats compared with the parental strains (Fig. 7A). Quantitative analysis of the images revealed no difference in fiber area between the strains (Fig. 7B), but the SS-16BN/Mcwi showed a significant increase in capillary number per fiber (Fig. 7C) and nearly significant increase in capillary density (P = 0.06, Fig. 7D).

Fig. 7.

Capillary and myocyte distribution in myocardium at 18 wk of age (×40 objective magnification). A: representative cross-sectional images of capillaries (in brown) and cardiomyocytes (outlined in red). Bar represents 100 μm. B: average cardiomyocyte cross-sectional area. C: average number of capillaries per cardiomyocyte. D: average capillary density (capillaries/μm2 × 10−3). All values taken from 18 wk old animals: SS/Mcwi n = 5; SS-16BN/Mcwi n = 6; BN n = 6. Results represent means ± SE. *P < 0.05 vs. SS; ‡P < 0.05 vs. BN (ANOVA).

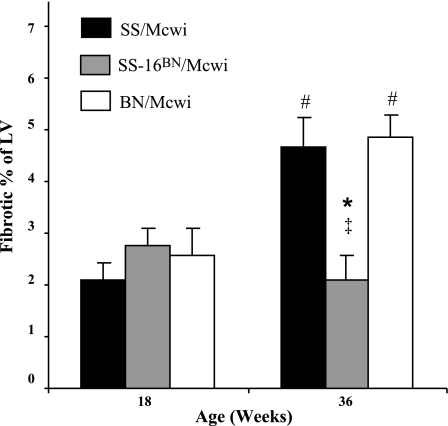

Fibrosis.

Both the SS/Mcwi and SS-16BN/Mcwi displayed minimal fibrosis at 18 wk of age (Fig. 8A). By 36 wk of age the SS/Mcwi and BN rats had significantly increased the percentage of fibrotic tissue in the LV. Both parental strains had nearly twice the fibrosis as the SS-16BN/Mcwi rats, which did not show an increase in fibrotic tissue with age.

Fig. 8.

Left ventricular fibrosis with aging. PVAN measurements made in SS/Mcwi (n = 6 at 18 wk, n = 3 at 36 wk), SS-16BN/Mcwi (n = 6 at 18 wk, n = 6 at 36 wk), and BN/Mcwi (n = 5 at 18 wk, n = 3 at 36 wk). Results represent means ± SE. *P < 0.05 vs. SS; ‡P < 0.05 vs. BN; #P <0.05 vs. 18 wk value within strain (ANOVA).

DISCUSSION

In the current study we have identified a consomic model derived from SS/Mcwi and BN rats that is better protected from developing phenotypes associated with age and/or disease-related deterioration in cardiac function than either parental strain. The consomic rat model, in combination with its genetic controls, provides a number of potential advantages over knockout or surgical models of hypertrophy and heart failure. First, and perhaps most importantly, the SS-16BN/Mcwi rat provides a model of early transient idiopathic LVH that does not progress to heart failure. This model was generated by combining naturally occurring alleles from SS/Mcwi and BN rats. The genetic similarity of the SS-16BN/Mcwi and the parental SS/Mcwi rat, along with the availability of the chromosome 16 donor BN rat, provide the unique opportunity to characterize both the progression to heart failure in the SS/Mcwi and the identity of genes on chromosome 16 contributing to protection. Unlike knockout or transgenic models, this set of animals could lead to the identification of a unique gene or gene combination that helps to explain the difference between LVH that progresses to heart failure and that which does not. Finally, because the transfer of BN chromosome 16 also normalizes blood pressure, the SS-16BN/Mcwi provides an opportunity to study LVH in a normotensive strain and understand the role elevated blood pressure may play in the progression to failure in the SS/Mcwi rat.

In this study LV morphology and function were measured as the rats aged on a normal (1%) salt diet to determine if the SS-16BN/Mcwi rat is a model of HCM. We were aiming to create a diet condition that would allow any genetic hypertrophy to be revealed in the consomic rat without causing excessive hypertension induced LVH in the parental SS. By 36 wk of age distinct differences between the strains became apparent. On a 1% salt diet 38% of SS/Mcwi died before reaching 36 wk of age. Any diet with a higher salt content would have increased the progression of mortality in these animals and eliminated the possibility for comparative studies in aged animals.

Our studies found that although 18 wk old SS-16BN/Mcwi rats have LVH compared with BN, they do not exhibit any phenotypes consistent with HCM such as a progressive inappropriate hypertrophy, reduced LV capillary density (23, 27, 31), or elevated LV interstitial fibrosis (1, 14, 30). Despite early LVH in the SS-16BN/Mcwi wall thickness did not continue to increase between 9 and 18 wk of age. In addition there is no increase in body weight normalized ventricle weight in the SS-16BN/Mcwi between 18 and 36 wk of age. Additionally, the average myocyte area, capillary density, and fibrotic content were unchanged in the SS-16BN/Mcwi during this time period. In fact, we found that the myocardium of the SS-16BN/Mcwi rat had a higher number of capillaries per myocyte than the either the SS/Mcwi or the BN rat. Based on these findings we conclude that this strain is not a model of HCM. At the later time points of 18 and 36 wk of age the intermediate wall thickness measured in the SS-16BN/Mcwi can be attributed to blood pressure between that of the SS/Mcwi and BN rats.

With aging there are changes in cardiac phenotype that are associated with reduced cardiac function. Among those that have been reported in rodents are LVH, dilation, fibrosis, systolic impairment, and impairment of β-adrenergic receptor signal transduction (2–4, 6–12, 19, 28, 33–36). By 36 wk of age SS/Mcwi rats exhibit all of these phenotypes, which lead to an overall decrease in LV function and indicate the development of heart failure. It is important to note that the age-related changes seen in the SS/Mcwi may be augmented by pathological changes caused by their hypertension.

Despite progressive increase in cardiac mass in all strains with age, only the SS/Mcwi had a significant increase in ventricle/body weight between 18 and 36 wk of age, which resulted from both an increased wall thickness and dilation of the LV chamber. This indicated LVH excessive to what can be attributed to normal body growth in the SS/Mcwi rat. The presence of hypertension in the SS/Mcwi makes it difficult to separate the influence of high afterload on the heart from the influence of the SS/Mcwi genome on the development of age-related phenotypes. However, the data from the SS-16BN/Mcwi and BN rat can help separate the role of pressure vs. genetic background. For example, the aged normotensive BN rats displayed some of the age-related cardiac phenotypes including increased LV fibrosis, reduced baseline fractional shortening, and impaired systolic function (Ees), suggesting that elevated pressure is not required for these phenotypes to develop in this model.

The only age-related phenotypes observed in the SS-16BN/Mcwi were LVH and dilation. The SS-16BN/Mcwi rat was protected from systolic dysfunction and pathological LV remodeling that occurs with aging despite exhibiting early idiopathic LVH (from 8–10 wk) comparable to that of SS/MCWi rats. These phenotypes demonstrate how the unique combination of SS/Mcwi and BN genes in the SS-16BN/Mcwi rat produce a resistant phenotype despite susceptibility to age-related deterioration and/or disease in both parental strains. This may be due to complex gene interactions between a gene or genes on the substituted chromosome and the rest of the genetic background.

It is usually assumed that chromosomal substitution between a diseased and nondiseased strain will result in one of the following: 1) complete rescue of the disease phenotype indicating substitution of a causative gene, 2) no change to the disease phenotype indicating that no genes on the chromosome are involved, or 3) intermediate expression of the disease phenotype indicating that the disease phenotype is probably polygenic. The functional and morphological data shown here indicate that the substitution of BN chromosome 16 into the SS/Mcwi results in many intermediate cardiac phenotypes as well as some that are unique to the SS-16BN/Mcwi. This could be due to the addition of BN chromosome 16, the loss of SS/Mcwi chromosome 16, or a combination of both. Together, these data suggest that phenotypes of LVH, cardiac function, and heart failure are complex polygenic traits and highlights the value of using consomic models to unravel their genetic causes.

Although it is difficult to speculate on the identity of the particular gene or genes on chromosome 16 that produce the observed phenotypes, several blood pressure quantitative trait loci have been reported on rat chromosome 16 (15, 25, 26, 29, 32). Further evidence that chromosome 16 contains genes that impact blood pressure and cardiac size came from a study by Moujahidine et al. (25). They reported that a congenic rat with Dahl S background and a segment of Lewis rat chromosome 16 showed significantly reduced blood pressure compared with the Dahl S rat. They also reported correlations between chromosome 16 congenics and increased heart-to-body weight and left ventricle-to-body weight ratios.

Together, these data indicate that the SS-16BN/Mcwi rat is a valuable model for investigating regulation of blood pressure and cardiac function with aging. Even in advanced aging BN chromosome 16 is capable of protecting the SS-16BN/Mcwi rat from developing hypertension and heart failure.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grants HL-66579 and HL-29598.

Address for reprint requests and other correspondence: A. S. Greene, Dept. of Physiology, Medical College of Wisconsin, 8701 Watertown Plank Rd., Milwaukee, WI 53226 (e-mail: agreene@mcw.edu).

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. The article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ackerman MJ Genetic testing for risk stratification in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and long QT syndrome: fact or fiction? Curr Opin Cardiol 20: 175–181, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anversa P, Li P, Sonnenblick EH, Olivetti G. Effects of aging on quantitative structural properties of coronary vasculature and microvasculature in rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 267: H1062–H1073, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anversa P, Palackal T, Sonnenblick EH, Olivetti G, Meggs LG, Capasso JM. Myocyte cell loss and myocyte cellular hyperplasia in the hypertrophied aging rat heart. Circ Res 67: 871–885, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anversa P, Puntillo E, Nikitin P, Olivetti G, Capasso JM, Sonnenblick EH. Effects of age on mechanical and structural properties of myocardium of Fischer 344 rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 256: H1440–H1449, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baan J, van der Velde ET, de Bruin HG, Smeenk GJ, Koops J, van Dijk AD, Temmerman D, Senden J, Buis B. Continuous measurement of left ventricular volume in animals and humans by conductance catheter. Circulation 70: 812–823, 1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boluyt MO, Converso K, Hwang HS, Mikkor A, Russell MW. Echocardiographic assessment of age-associated changes in systolic and diastolic function of the female F344 rat heart. J Appl Physiol 96: 822–828, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boluyt MO, Devor ST, Opiteck JA, White TP. Age effects on the adaptive response of the female rat heart following aortic constriction. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 55: B307–B314, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boluyt MO, Opiteck JA, Esser KA, White TP. Cardiac adaptations to aortic constriction in adult and aged rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 257: H643–H648, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Capasso JM, Fitzpatrick D, Anversa P. Cellular mechanisms of ventricular failure: myocyte kinetics and geometry with age. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 262: H1770–H1781, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Capasso JM, Palackal T, Olivetti G, Anversa P. Severe myocardial dysfunction induced by ventricular remodeling in aging rat hearts. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 259: H1086–H1096, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Capasso JM, Puntillo E, Olivetti G, Anversa P. Differences in load dependence of relaxation between the left and right ventricular myocardium as a function of age in rats. Circ Res 65: 1499–1507, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cheng W, Reiss K, Li P, Chun MJ, Kajstura J, Olivetti G, Anversa P. Aging does not affect the activation of the myocyte insulin-like growth factor-1 autocrine system after infarction and ventricular failure in Fischer 344 rats. Circ Res 78: 536–546, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cowley AW Jr, Liang M, Roman RJ, Greene AS, Jacob HJ. Consomic rat model systems for physiological genomics. Acta Physiol Scand 181: 585–592, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Franz WM, Muller OJ, Katus HA. Cardiomyopathies: from genetics to the prospect of treatment. Lancet 358: 1627–1637, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garrett MR, Dene H, Walder R, Zhang QY, Cicila GT, Assadnia S, Deng AY, Rapp JP. Genome scan and congenic strains for blood pressure QTL using Dahl salt-sensitive rats. Genome Res 8: 711–723, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Georgakopoulos D, Kass DA. Assessment of cardiovascular function in the mouse using pressure-volume relationship. Acta Physiol Scand 18: 101–112, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 17. http://pga.mcw.edu

- 18.Ikeda S, Hamada M, Qu P, Hiasa G, Hashida H, Shigematsu Y, Hiwada K. Relationship between cardiomyocyte cell death and cardiac function during hypertensive cardiac remodelling in Dahl rats. Clin Sci (Lond) 102: 329–335, 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kajstura J, Cheng W, Sarangarajan R, Li P, Li B, Nitahara JA, Chapnick S, Reiss K, Olivetti G, Anversa P. Necrotic and apoptotic myocyte cell death in the aging heart of Fischer 344 rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 271: H1215–H1228, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kang PM, Yue P, Liu Z, Tarnavski O, Bodyak N, Izumo S. Alterations in apoptosis regulatory factors during hypertrophy and heart failure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 287: H72–H80, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kannel WB Left ventricular hypertrophy as a risk factor: the Framingham experience. J Hypertens Suppl 9: S3–S8, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klotz S, Hay I, Zhang G, Maurer M, Wang J, Burkhoff D. Development of heart failure in chronic hypertensive Dahl rats: focus on heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Hypertension 47: 901–911, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marcus ML The Coronary Circulation in Health and Disease. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1983.

- 24.Millar Instruments I. Millar Pressure-Volume Systems MPVS-300/400 Series Owner's Guide. Document number: 004–2142.

- 25.Moujahidine M, Dutil J, Hamet P, Deng AY. Congenic mapping of a blood pressure QTL on chromosome 16 of Dahl rats. Mamm Genome 13: 153–156, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moujahidine M, Lambert R, Dutil J, Palijan A, Sivo Z, Ariyarajah A, Deng AY. Combining congenic coverage with gene profiling in search of candidates for blood pressure quantitative trait loci in Dahl rats. Hypertens Res 27: 203–212, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.O'Gara PT, Bonow RO, Maron BJ, Damske BA, Van Lingen A, Bacharach SL, Larson SM, Epstein SE. Myocardial perfusion abnormalities in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: assessment with thallium-201 emission computed tomography. Circulation 76: 1214–1223, 1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pacher P, Mabley JG, Liaudet L, Evgenov OV, Marton A, Hasko G, Kollai M, Szabo C. Left ventricular pressure-volume relationship in a rat model of advanced aging-associated heart failure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 287: H2132–H2137, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schork NJ, Krieger JE, Trolliet MR, Franchini KG, Koike G, Krieger EM, Lander ES, Dzau VJ, Jacob HJ. A biometrical genome search in rats reveals the multigenic basis of blood pressure variation. Genome Res 5: 164–172, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Seidman JG, Seidman C. The genetic basis for cardiomyopathy: from mutation identification to mechanistic paradigms. Cell 104: 557–567, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spaan JAE Coronary Blood Flow: Mechanics, Distribution and Control. Boston: Kluwer Academic, 1991.

- 32.Stoll M, Kwitek-Black AE, Cowley AW Jr, Harris EL, Harrap SB, Krieger JE, Printz MP, Provoost AP, Sassard J, Jacob HJ. New target regions for human hypertension via comparative genomics. Genome Res 10: 473–482, 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thomas DP, Cotter TA, Li X, McCormick RJ, Gosselin LE. Exercise training attenuates aging-associated increases in collagen and collagen crosslinking of the left but not the right ventricle in the rat. Eur J Appl Physiol 85: 164–169, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thomas DP, McCormick RJ, Zimmerman SD, Vadlamudi RK, Gosselin LE. Aging- and training-induced alterations in collagen characteristics of rat left ventricle and papillary muscle. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 263: H778–H783, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thomas DP, Zimmerman SD, Hansen TR, Martin DT, McCormick RJ. Collagen gene expression in rat left ventricle: interactive effect of age and exercise training. J Appl Physiol 89: 1462–1468, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xiao RP, Lakatta EG. Deterioration of beta-adrenergic modulation of cardiovascular function with aging. Ann NY Acad Sci 673: 293–310, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]