Abstract

Reactive airway disease predisposes patients to episodes of acute smooth muscle mediated bronchoconstriction. We have for the first time recently demonstrated the expression and function of endogenous ionotropic GABAA channels on airway smooth muscle cells. We questioned whether endogenous GABAA channels on airway smooth muscle could augment β-agonist-mediated relaxation. Guinea pig tracheal rings or human bronchial airway smooth muscles were equilibrated in organ baths with continuous digital tension recordings. After pretreatment with or without the selective GABAA antagonist gabazine (100 μM), airway muscle was contracted with acetylcholine or β-ala neurokinin A, followed by relaxation induced by cumulatively increasing concentrations of isoproterenol (1 nM to 1 μM) in the absence or presence of the selective GABAA agonist muscimol (10–100 μM). In separate experiments, guinea pig tracheal rings were pretreated with the large conductance KCa channel blocker iberiotoxin (100 nM) after an EC50 contraction with acetylcholine but before cumulatively increasing concentrations of isoproterenol (1 nM to 1 uM) in the absence or presence of muscimol (100 uM). GABAA activation potentiated the relaxant effects of isoproterenol after an acetylcholine or tachykinin-induced contraction in guinea pig tracheal rings or an acetylcholine-induced contraction in human endobronchial smooth muscle. This muscimol-induced potentiation of relaxation was abolished by gabazine pretreatment but persisted after blockade of the maxi KCa channel. Selective activation of endogenous GABAA receptors significantly augments β-agonist-mediated relaxation of guinea pig and human airway smooth muscle, which may have important therapeutic implications for patients in severe bronchospasm.

Keywords: guinea pig, organ bath, gabazine, muscimol

asthma is a chronic inflammatory disease of the airways the prevalence of which both in the United States and throughout much of the world has taken on pandemic proportions (4). Standard treatment for asthma centers on pharmacological attenuation of hyperresponsiveness either by modulation of inflammatory mediators or by promoting airway smooth muscle (ASM) relaxation (e.g., β2-adrenoceptor agonists). Although research over the past three decades has made great strides in elucidating many of the underlying mechanisms involved in this disease, few novel additions to the pharmacological armamentarium have occurred in the treatment of reactive airway disease.

β2-Adrenoceptor agonists retain a prominent role in the clinical treatment of airway hyperresponsiveness, and the mechanisms by which β2-adrenoceptor agonists relax ASM include both cAMP-dependent and cAMP-independent pathways. Additionally, regulation of β2-adrenoceptor activity either through desensitization or downregulation also modulates the magnitude of relaxation. Although it may be possible to improve β-adrenoceptor-mediated relaxation at the level of the receptor or at multiple downstream signaling proteins, it is possible that alternative cell surface receptors or channels may act synergistically with β2-adrenoceptor signaling to improve ASM relaxation.

Our laboratory (22) has recently reported the novel description of γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) channels on ASM. The GABA channel family consists of both ionotropic (GABAA) channels and metabotropic (GABAB) receptors (1). In neuronal cells, activation of GABAA channels on mature neurons leads to inhibitory plasma membrane hyperpolarization via the inward flux of chloride ions (31, 33). Hyperpolarization of the ASM cell membrane is in part responsible for the potent relaxant effects observed with β2-adrenoceptor agonists (18) via opening of large-conductance calcium-activated potassium channels (maxi-KCa; Refs. 14, 15, 20, 35). Thus hyperpolarization via inward flux of chloride through GABAA channels and opening of KCa channels by β-adrenoceptor agonists share mechanistic overlap.

Additionally, two other mechanisms by which inward chloride flux and hyperpolarization could promote synergistic ASM relaxation include impairment of sarcoplasmic calcium release by disrupting the ability of sarcolemmal chloride channels to balance charge generation (10) and the attenuation of depolarization required for inward calcium flux via voltage-dependent calcium channels (5, 29, 34).

Given the fundamental mechanism by which activation of GABAA channels result in hyperpolarization via inward chloride current on neuronal cells, we questioned whether these newly identified GABAA channels on ASM can augment isoproterenol-mediated relaxation and whether such potentiation occurs independent of relaxation achieved due to the opening of the maxi K+ channel.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents.

Indomethacin, N-vanillyinonanamide (capsaicin analog), muscimol, pyrilamine, isoproterenol, acetylcholine, and gabazine were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Tetrodotoxin and the neurokinin receptor 2 agonist β-ala neurokinin A (NKA) fragment 4–10 were obtained from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA), and MK571 was obtained from Biomol (Plymouth Meeting, PA).

Guinea pig tracheal rings.

All animal protocols were approved by the Columbia University Animal Care and Use Committee. Male Hartley guinea pigs (GPs; ∼400 g) were deeply anesthetized with intraperitoneal pentobarbital (100 mg/kg). After the chest cavity was opened, the entire trachea was surgically removed and promptly placed in cold (4°C) PBS. Each trachea was dissected under a dissecting microscope into closed rings comprised of two cartilaginous segments from which mucosa and connective tissue were removed. Tissues were placed into cold Krebs-Henseleit (KH) buffer (in mM: 118 NaCl, 5.6 KCl, 0.5 CaCl2, 0.24 MgSO4, 1.3 NaH2PO4, 25 NaHCO3, and 5.6 glucose, pH 7.4) containing indomethacin 10 μM (DMSO vehicle final concentration in organ baths of 0.01%) to block tone due to endogenous release of prostanoids.

Human ASM strips.

Studies were approved by Columbia University's Institutional Review Board and deemed not human subjects research under 45 CFR 46. Human ASM was obtained from discarded regions of healthy donor lungs harvested for lung transplantation at Columbia University. Upon availability, this excess tissue was transported to the laboratory in cold (4°C) KH buffer (composition as above). With the use of a dissecting microscope, human ASM strips (∼5-mm wide) were dissected from the posterior region of either the lower trachea or first mainstem broncus and cut parallel to the orientation of the cartilaginous rings.

Organ baths.

Closed GP tracheal rings or human ASM was suspended in organ baths as previously described (16). Briefly, tissues were attached with silk thread inferiorly to a fixed tissue hook in a water-jacketed (37°C) 2-ml organ bath (Radnoti Glass Technology, Monrovia, CA) and superiorly to a Grass FT03 force transducer (Grass Telefactor, West Warwick, RI) coupled to a computer via BioPac hardware and Acqknowledge 7.3.3 software (Biopac Systems, Goleta, CA) for continuous digital recording of muscle force. Tissues were secured such that muscle contraction would align with the vertical plane between the anchoring hook below and transducer above. KH buffer was continuously bubbled with 95%O2-5% CO2, and tissues were allowed to equilibrate at 1 g (GP rings) or 1.5 g (human ASM strips) isotonic force for 1 h with fresh KH buffer changes every 15 min.

Preliminary contractile challenges.

After equilibration, the capsaicin analog N-vanillylnonanamide (10 μM final) was added to the organ baths containing GP tracheal rings to first activate and then deplete nonadrenergic, noncholinergic nerves. After N-vanillylnonanamide induced force had returned to baseline (∼50 min), the KH buffer in the organ baths was changed six times to wash out added or liberated mediators. Tracheal rings were then subjected to two cycles of increasing cumulative concentrations of acetylcholine (0.1 μM to 1 mM) with six buffer changes and resetting of the resting tension between cycles. In contrast, human ASM preparations required three cycles of acetylcholine concentration-response (0.1 μM to 1 mM) challenges to produce stable responses. The resulting concentration-response curves were then used to determine the EC50 concentrations of acetylcholine required for each individual ring or strip. Individual tissues have variable sensitivity to contractile agonists (EC50) and variation in the magnitude of contraction (Emax). To avoid bias between treatment groups, tissues were contracted to individually calculated EC50 for acetylcholine, and tissues with similar Emax values were randomly assigned to treatments within individual experiments.

After preliminary contractile challenges, tissues were subjected to extensive KH buffer changes (8–9 times) and allowed to stabilize at their respective isotonic resting tensions (1.0 and 1.5 g for GP and human, respectively). To remove confounding effects of other procontractile pathways each bath received a complement of antagonists 20 min before subsequent contractile challenge. The antagonists included pyrilamine (10 μM; H1 histamine receptor antagonist), tetrodotoxin (1 μM; antagonist of endogenous neuronal-mediated cholinergic or C-fiber effects), and MK571 (10 μM; leukotriene D4 antagonist: human ASM only).

In vitro assessment of GABAA agonist effect on β2-adrenoceptor-mediated ASM relaxation after an EC50 contractile stimulus with acetylcholine.

Each GP ring or human bronchial smooth muscle strip was contracted with an EC50 concentration of acetylcholine and was allowed to achieve a steady-state plateau of increased force (typically 15 min). Tissues were randomly assigned to one of three groups. The control group received cumulatively increasing concentrations of isoproterenol in half-log increments (in GP: 1 nM to 10 μM, and in human: 5 nM to 10 μM). To determine the effect of selective GABAA activation on isoproterenol-mediated relaxation, a single dose of muscimol (100 μM in human or 100 or 10 μM in GP) was added to the study group immediately before (∼5 s) the first dose of isoproterenol (1 nM in GP and 5 nM in human, respectively). To confirm the effect of muscimol was not attributable to nonspecific effects, a third group received pretreatment (15 min before contractile challenge) with the selective GABAA antagonist gabazine (100 μM), followed by muscimol 5 s before the first dose of isoproterenol.

In vitro assessment of GABAA agonist effect on β2-adrenoceptor-mediated ASM relaxation after contractile stimulus with β-ala NKA (0.1 uM).

To ascertain whether the relaxant effect after GABAA activation was dependent on the contractile stimulus used, we reassessed the ability of muscimol to potentiate β2-adrenoceptor-mediated ASM relaxation after a contractile stimulus with a neurokinin receptor 2 (NK2) agonist. With the use of the same paradigm outlined above, GP rings underwent preliminary contractile challenges with the capsaicin analog and acetylcholine. After they were extensively washed and the baseline resting tone was reset (1.0 g), rings were treated with the NK2 agonist β-ala NKA fragment 4–10 (0.1 uM). As before, after this contractile stimulus, rings were treated with cumulatively increasing concentrations of isoproterenol in half-log increments (1 nM to 10 μM) in the presence or absence of the selective GABAA agonist muscimol (100 μM).

In vitro assessment of GABAA agonist effect on β2-adrenoceptor-mediated ASM relaxation after blockade of the maxi K+ channel.

To determine if the relaxation observed between the β2-adrenoceptor agonist and GABAA agonist could be attributed to the effects at the maxi K+ channel, a separate group of experiments using GP tracheal rings were conducted. After the identical preliminary contractile challenges as above, GP tracheal rings were contracted with an EC50 concentration of acetylcholine and were allowed to achieve a steady-state plateau of contraction. A subset of rings were then treated with the selective maxi K+ channel inhibitor iberiotoxin (0.1 μM) and allowed to equilibrate over 15 min. All rings then received cumulatively increasing concentrations of isoproterenol in half-log increments (1 nM to 10 μM) in the absence or presence of a single dose of the selective GABAA agonist muscimol (100 μM) administered just before a minimally effective concentration of isoproterenol under this regimen (10−7.5 M).

Statistical analysis.

Each experimental permutation included intra-experimental controls. Cumulative concentration-response curves were generated and the EC50 or Emax for isoproterenol was determined for each experimental condition where appropriate. Statistical analysis was performed using either one way ANOVA, followed by Bonferroni posttest comparison, or in those instances when two groups where under comparison a two-tailed Student t-test was used using Prism 4.0 software (GraphPad, San Diego, CA). Data are presented as means ± SE; P < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

GABAA channel agonist augments isoproterenol-mediated ASM relaxation after an acetylcholine EC50 contraction in GP and human ASM.

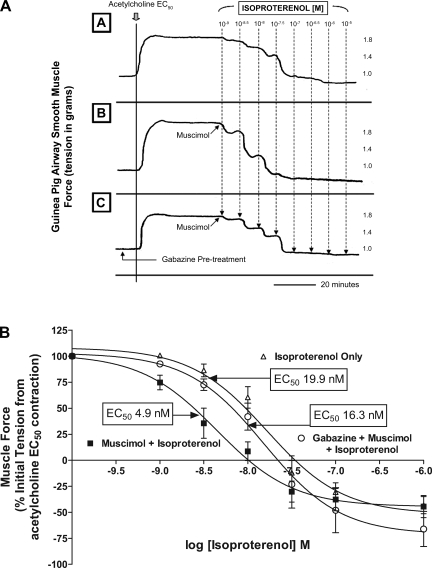

Selective GABAA activation with muscimol significantly potentiated the relaxant effects of isoproterenol after an acetylcholine contraction (Fig. 1A). In GP tracheal rings, cotreatment with muscimol and isoproterenol resulted in a significant leftward shift in the isoproterenol relaxation concentration-response curve compared with treatment with isoproterenol alone [EC50= 4.9 ± 0.8 nM (n = 7) vs. 19.9 ± 0.4 nM (n = 6), respectively; P < 0.01 (Fig. 1B)]. To prove that the shift in EC50 observed was due to selective and specific activation of GABAA channels, pretreatment with the selective antagonist gabazine was performed. Pharmacological antagonism of GABAA activation with gabazine significantly reversed the potentiation of muscimol of isoproterenol-mediated relaxation [EC50= 16.3 ± 2 nM (n = 8) vs. EC50= 4.9 ± 0.8 nM (n = 7) respectively; P < 0.05] after an acetylcholine contractile stimulus and returned the concentration-response curve toward baseline [treatment with isoproterenol alone; EC50= 16.3 ± 2 nM (n = 8) vs. 19.9 ± 0.4 nM (n = 6), respectively; P > 0.05]. In addition to a significant shift in the EC50 of the isoproterenol concentration-response curve by muscimol, selective activation of the GABAA channel resulted in a significant potentiation of relaxation even at a low dose of isoproterenol [1 nM; Fig. 2; muscle force = 74.7 ± 6.9% (n = 7) of initial acetylcholine-induced force for muscimol plus isoproterenol vs. 98.9 ± 1.3% for isoproterenol alone (n = 4); P < 0.05], and this effect was completely reversed by gabazine in the presence of muscimol [muscle force = 92.6 ± 2.8% (n = 8); P < 0.05]. To investigate if lower concentrations of muscimol also potentiated isoproterenol-mediated relaxation, we examined the degree of relaxation achieved with a single concentration of muscimol (10 uM) administered with isoproterenol (5 nM) compared with the relaxant effects of 5 nM isoproterenol alone. We found a significant enhancement of relaxation at this lower dose of GABAA agonist (46.5 ± 8.6% of initial acetylcholine-induced tension; n = 4) compared with 5 nM isoproterenol alone (81.6 ± 4.2% of initial acetylcholine-induced tension; n = 13; P < 0.01).

Fig. 1.

Selective GABAA activation potentiates β- adrenoceptor-mediated guinea pig airway smooth muscle relaxation after an acetylcholine contraction. A: representative tracings in force/time of guinea pig tracheal rings after an acetylcholine contraction followed by increasing concentrations of isoproterenol in the presence or absence of muscimol and/or gabazine. Top tracing (A) is isoproterenol alone, middle tracing (B) is muscimol and isoproterenol, and bottom tracing (C) represents treatment with muscimol and isoproterenol after pretreatment with gabazine. B: compiled isoproterenol concentration-response curves comparing treatment with isoproterenol only (▵) to isoproterenol after a single concentration of 100 μM muscimol (▪) and isoproterenol with a single concentration of 100uM muscimol subsequent to 100 μM gabazine pretreatment (○). GABAA activation of guinea pig airway smooth muscle results in a several fold reduction in the EC50 for isoproterenol response, and this muscimol effect is eliminated by gabazine pretreatment.

Fig. 2.

Relaxation with low-dose isoproterenol (1 nM) is significantly enhanced by selective GABAA activation in guinea pig tracheal rings. Relaxation (%change in muscle force) achieved with 1 nM isoproterenol after an EC50 acetylcholine contraction. The addition of a single concentration of muscimol (100 uM) significantly augmented β-adrenoceptor-mediated relaxation (muscle force = 74.7 ± 6.9%; n = 7) of initial acetylcholine-induced force for muscimol with isoproterenol (1 nM) vs. 98.9 ± 1.3% for treatment with isoproterenol (1 nM) alone (n = 4; #P < 0.01). and this effect was reversed by gabazine [muscle force = 92.6 ± 2.8% (n = 8); $P < 0.05].

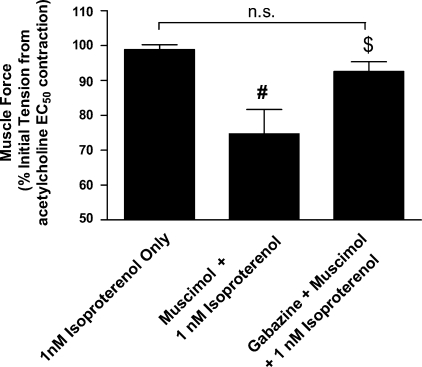

In human ASM tissues, selective GABAA activation also significantly potentiated the relaxant effects of isoproterenol after an acetylcholine contraction. As was observed in GP ASM, a single administration of muscimol (100 μM) given 5 s before the 5-nM isoproterenol dose in human tissues augmented the magnitude of β-adrenoceptor-mediated relaxation (Fig. 3A). This prorelaxant effect resulted in a leftward shift in the concentration-response curve achieved with isoproterenol and was associated with a significant change in the EC50 from 83.4 ± 26.1 nM (n = 8) for the isoproterenol only treated tissues to an EC50 of 19.7 ± 5.0 nM (n = 13) in tissues treated with both muscimol and isoproterenol (P < 0.05). As in GP tracheal rings, selectivity of GABAA activation was established by a reversal of the muscimol effect upon pretreatment with 100uM gabazine [EC50 of 71.7 ± 16.4 nM (n = 12); P > 0.05 compared with isoproterenol alone; Fig. 3B].

Fig. 3.

Selective GABAA activation augments β-adrenoceptor-mediated airway relaxation after an acetylcholine contraction in human airway smooth muscle. A: representative tracings in force/time of human airway smooth muscle after an acetylcholine contraction followed by increasing concentrations of isoproterenol in the presence or absence of muscimol and/or gabazine. Top tracing (A) is isoproterenol alone, middle tracing (B) is muscimol and isoproterenol, and bottom tracing (C) represents treatment with muscimol and isoproterenol after pretreatment with gabazine. B: compiled isoproterenol concentration-response curves comparing treatment with isoproterenol only (▵) to isoproterenol after a single concentration of 100 μM muscimol (▪) and isoproterenol with a single concentration of 100 μM muscimol subsequent to 100 μM gabazine pretreatment (○). Activation of GABAA channels on human airway smooth muscle results in a severalfold reduction in the EC50 for isoproterenol-mediated relaxation, and this effect is blocked by gabazine pretreatment.

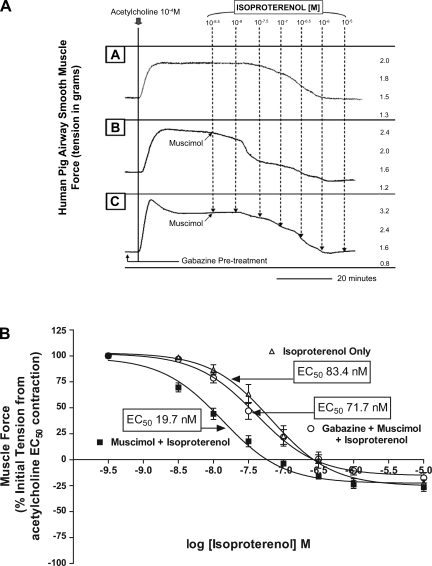

GABAA channel agonist augments isoproterenol-mediated relaxation after an NK2 EC80 contraction in GP ASM.

To illustrate that GABAA augmentation of β-adrenoceptor ASM relaxation was not limited to a single contractile agonist (i.e., acetylcholine), isoproterenol-mediated relaxation in the absence or presence of muscimol was repeated after substitution of acetylcholine with a contractile agonist acting via the NK2 receptor (β-ala NKA fragment 4–10). After an estimated EC80 contraction with β-ala NKA fragment 4–10, significantly increased relaxation by isoproterenol occurred in the presence of endogenous GABAA activation [EC50 of 12.7 ± 2.5 nM (n = 6) with isoproterenol only vs. EC50 of 0.77 ± 0.19 nM (n = 6); P < 0.01 with the addition of 1 mM muscimol; Fig. 4].

Fig. 4.

GABAA potentiation of β-adrenoceptor-mediated guinea pig airway smooth muscle relaxation occurs after contractile stimulus with an neurokinin A (NKA) agonist (10−7M β-ala fragment 4–10). Compiled isoproterenol concentration-response curves after an β-ala NKA-mediated (EC80) contractile stimulus, comparing treatment with isoproterenol only (▵) to isoproterenol concentration response after a single dose of 10−3M muscimol (▪). Activation of GABAA channels on guinea pig airway smooth muscle after a distinct contractile agonist results in a dramatic reduction in the EC50 for isoproterenol-mediated relaxation.

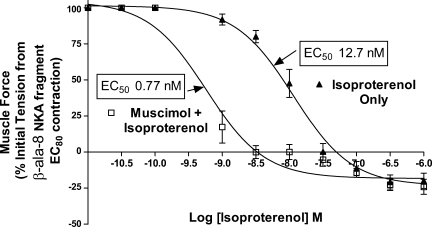

GABAA activation augments GP ASM relaxation from an acetylcholine EC50 contraction independent of maxi-K channel inhibition.

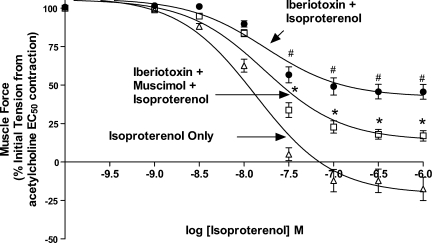

To establish that the prorelaxant effect of GABAA activation on ASM occurs independently from a membrane hyperpolarization effect achieved through the maxi-K channel, we examined the ability of muscimol to promote isoproterenol-mediated relaxation under conditions where this channel was selectively blocked by iberiotoxin. As previously shown (14), treatment with iberiotoxin significantly reduced the degree of maximal relaxation induced by isoproterenol in GP ASM after an EC50 acetylcholine contraction [55.6 ± 5.4% (n = 17) vs. 116 ± 7.9% (n = 11) for the presence or absence of iberiotoxin respectively; P < 0.001, Fig. 5]. Muscimol (100 uM) increased the maximal relaxation induced by isoproterenol even after maxi-K channel blockade with iberiotoxin [82.0 ± 3.1% (n = 17) vs. 55.6 ± 5.4% (n = 17), respectively; P < 0.01 for isoproterenol and iberiotoxin compared with isoproterenol, iberiotoxin, and muscimol].

Fig. 5.

GABAA activation potentiates guinea pig ASM relaxation from acetylcholine EC50 independent of maxi-K channel inhibition. Compiled isoproterenol concentration-response curves comparing treatment with isoproterenol only (▵) to isoproterenol after maxi-K channel inhibition with 0.1uM iberiotoxin (•), and isoproterenol after 0.1 μM iberiotoxin with a single dose of muscimol (100 uM; □). Treatment with iberiotoxin (•) resulted in an impairment in Emax for relaxation compared with treatment with isoproterenol only (▵; concentrations denoted as #P < 0.05); 100 μM muscimol treatment after iberiotoxin treatment (□) improved Emax for isoproterenol-mediated relaxation compared with isoproterenol after maxi-K channel inhibition with 0.1 μM iberiotoxin (▪; concentrations denoted as *P < 0.05).

DISCUSSION

The major finding of this study is that activation of endogenous GABAA channels on ASM facilitates β-adrenoceptor-mediated relaxation. To establish the relevance of our findings, we used ASM from two species (GP and human) and tested the prorelaxant effect against two contractile agonists (muscarinic and neurokinin receptor agonists). In addition, to illustrate that the effect we observed was specific to activation of endogenous GABAA channels, we demonstrate that the selective pharmacological antagonist gabazine abolished the effect of the GABAA agonist (muscimol). The specificity for a GABAA channel effect is further supported by muscimol having significant effects at concentrations (10–100 uM) typically used to study GABAA channels in intact brain slices (26). This study is the first demonstration that endogenous GABAA activation can augment β-adrenoceptor-mediated relaxation in ASM.

It has been a long-standing belief that a GABAergic contribution to airway tone was largely mediated by GABAA channels in the brainstem (23) or GABAB channels on preganglionic cholinergic nerves in the lung (2, 37). However, there is emerging evidence that a far more complex GABAergic system exists, which involves the presence of GABA channels not only nerves but also on airway epithelium and ASM itself (22, 27, 41). This study was designed to specifically examine the role of ASM GABAA channels on relaxation, so several strategies were used to eliminate the effects of GABAA channels on other cell types in the airway from confounding the interpretation of our results. Epithelial or neuronal contributions were eliminated by denuding the epithelium and by capsaicin and tetrodotoxin pretreatments, respectively. Moreover, in isolated peripheral airway tissues studied in organ baths, exogenous electrical field stimulation is typically required for neuronal activation (and this was not a component of our methodology). Additionally, we utilized muscimol instead of GABA to selectively activate ASM GABAA channels, as GABA may activate GABAB channels on ASM and potentially counteract the prorelaxant effects of ASM GABAA channel activation.

The observation that activation of endogenous GABAA channels on ASM potentiates isoproterenol-mediated relaxation may have clinical relevance for several reasons. Asthma has long been characterized by hyperresponsiveness to stimuli that manifests as acute episodes of excessive smooth muscle contractility and reversible airway narrowing. Since β2-adrenoceptor agonists remain the most effective drug class capable of reversing this acute bronchoconstriction, they continue to be the cornerstone of asthma therapy. Yet, although β2-adrenoceptor agonists have been shown to acutely suppress hyperresponsiveness in vivo (3, 17), there are several concerns associated with their chronic use.

For example, bronchial hyperreactivity has been shown to actually increase in response to histamine under conditions of chronic salbutamol use (39) and increased respiratory related deaths have been associated with chronic salmeterol therapy (25). The potential mechanisms underlying these observations are complex and are not fully understood, but recent evidence (30, 32) suggests that prolonged exposure of human ASM cells to these drugs in vitro can augment spasmogen-mediated inositol phosphate production and thereby potentially exacerbate contractile tone in the airway. Although we did not study the effect that endogenous GABAA activation may confer in a model of prolonged β2-adrenoceptor agonist exposure, the facilitation of relaxation achieved by cotreatment (GABAA agonist and β2-adrenoceptor agonist) may provide better symptomatic relief at lower doses of β-agonists and theoretically could reduce the amount of β2-adrenoceptor agonist required for chronic maintenance therapy.

Another serious concern involves evidence that suggests that the milieu associated with asthma can lead to diminished effectiveness of these relaxant agents (38). Several studies (6–8) have shown increased expression of Gαi in animal models of asthma associated with an impairment in β2-adrenoceptor-mediated relaxation, and recent work (21) has established a complex role of Gαi2 as a direct regulator of β2-adrenoceptor-mediated relaxation due to direct coupling between signaling pathways at the level of Gi crosstalking to Gq and Gs. Given that activation of endogenous GABAA channels on both GP and human ASM resulted in an augmentation of β-adrenoceptor relaxation from a contracted state, the potential benefit of a GABAA agonist in the setting of β-adrenoceptor resistance is obvious. An important component of our findings that directly relates to this clinical concern is that we observed a significant degree of relaxation at low concentrations of isoproterenol (i.e., 1 nM), suggesting a potential benefit in scenarios where β-agonist resistance may be present.

β-Adrenoceptor-mediated relaxation of ASM is a complex process that involves a variety of mechanisms (18). Classically, β-adrenoceptor signaling involves stimulation of Gs allowing for the dissociation of its α-subunit (GTP bound), which then binds and activates adenylyl cyclase. The resultant synthesis of cAMP activates various cAMP-dependent protein kinases (i.e., PKA) as well as cGMP-dependent protein kinases (PKG). These both in turn can stimulate potassium conductance via the maxi-K channel (19, 28). In addition, there is evidence that β-adrenoceptor-mediated cAMP independent pathways can also activate maxi-K channels (19, 36). The significance of the maxi-K channel to functional relaxation in the airway with β-agonists is further substantiated by evidence that selective inhibition with iberiotoxin of the maxi-K channel greatly limits the degree of ASM relaxation achievable by β-adrenoceptor agonist treatment (14). Activation of the maxi-K channel results in egress of potassium and a resultant hyperpolarization, which can limit the free intracellular Ca2+ pool by its effect on L-type voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. Since activation of GABAA channels classically results in hyperpolarization (via inward chloride current), it may share a mechanistic overlap with β-adrenoceptor-mediated relaxation by a similar influence on ASM membrane potential.

Reports of potential interactions of GABA and bicuculline methiodide (GABAA antagonist) with voltage-gated K+ channels (11, 13, 24) raise the possibility of non-specific GABAA agonist effects at the maxi-K channel contributing to the prorelaxant effects we observed. To illustrate that GABAA channel augmentation of isoproterenol-mediated relaxation occurs independent of relaxation achieved due to opening of the maxi K+ channel, we performed experiments under conditions of iberiotoxin blockade of the maxi K+ channel. Iberiotoxin-mediated inhibition of GP smooth muscle relaxation after β-agonist treatment closely correlated with work by other investigators (14). Yet, under these conditions, we observed a significant improvement in isoproterenol-mediated relaxation with the addition of muscimol, suggesting the prorelaxant effects we observed are not due to nonspecific effects mediated through the maxi-K channel.

Although dicephering other mechanisms by which GABAA channel activation may potentiate β-adrenoceptor relaxation in ASM was beyond the scope of the current study, the functional improvement that GABAA channel activation contributes to β-adrenoceptor-mediated relaxation in ASM may not be solely related to prorelaxant effects derived from inhibition of the L-type voltage gated Ca2+ channel as a consequence of plasma membrane hyperpolarization but may instead more importantly relate to handling of intracellular chloride (Cl−) and its coupling to sarcoplasmic calcium release. There is evidence that plasma membrane Ca2+ dependent Cl− channels are activated in ASM after procontractile stimuli and can allow for the egress of chloride out of the cell (12, 40), which not only promotes plasma membrane depolarization, but may also provide a favorable gradient for subsequent sarcolemmal Ca2+ handling during procontractile stimuli (9). Recent evidence (10) suggests that voltage-dependent sarcolemmal Cl− channels balance and neutralize charge generation of the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) during Ca2+ release via concomitant SR chloride efflux into the cytosol. However, a factor that may contribute to a reduction of outward flux of chloride from the SR (and thereby inhibit SR Ca2+ release) is the accumulation of cytosolic chloride after the plasma membrane reversal potential for chloride has been surpassed during depolarization. Indeed, depolarization of the plasma membrane after muscarinic receptor-induced contraction exceeds the plasma membrane chloride reversal potential in ASM (40). Therefore, after a muscarinic contractile stimulus, activation of ASM GABAA channels would then allow for the reentry of chloride into the cell resulting in plasma membrane hyperpolarization, diminished chloride efflux from the SR, and impaired SR calcium release. Therefore, since GABAA channel activation after a procontractile muscarinic stimulus may promote increased cytosolic chloride, it may be potentiating β-adrenoceptor relaxation by indirectly limiting SR Ca2+ release.

One notable difference between GP and human ASM in the current study was the measured EC50 for isoproterenol relaxation (19.9 ± 0.4 vs. 83.5 ± 26.1 nM, respectively). These differences are likely due to the longer time period between tissue harvest and subsequent in vitro study in organ baths. Whereas GP tracheal rings were typically in organ baths within 40 min of harvest, there were considerable delays (12–30 h) between harvest and study of human tissues.

In summary, these studies provide novel evidence that selective pharmacological activation of endogenous GABAA channels on ASM potentiates β-adrenoceptor relaxation in vitro in both GP and human ASM.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institute of General Medical Sciences Grant GM-065281 (to C. W. Emala), GM-071485 (to J. Yang).

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. The article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bormann J The “ABC” of GABA receptors. Trends Pharmacol Sci 21: 16–19, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chapman RW, Danko G, Rizzo C, Egan RW, Mauser PJ, Kreutner W. Prejunctional GABA-B inhibition of cholinergic, neurally-mediated airway contractions in guinea-pigs. Pulm Pharmacol 4: 218–224, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheung D, Timmers MC, Zwinderman AH, Bel EH, Dijkman JH, Sterk PJ. Long-term effects of a long-acting beta 2-adrenoceptor agonist, salmeterol, on airway hyperresponsiveness in patients with mild asthma. N Engl J Med 327: 1198–1203, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eder W, Ege MJ, von ME. The asthma epidemic. N Engl J Med 355: 2226–2235, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ghatta S, Nimmagadda D, Xu X, O'Rourke ST. Large-conductance, calcium-activated potassium channels: structural and functional implications. Pharmacol Ther 110: 103–116, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hakonarson H, Herrick DJ, Grunstein MM. Mechanism of impaired beta-adrenoceptor responsiveness in atopic sensitized airway smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 269: L645–L652, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hakonarson H, Herrick DJ, Serrano PG, Grunstein MM. Mechanism of cytokine-induced modulation of beta-adrenoceptor responsiveness in airway smooth muscle. J Clin Invest 97: 2593–2600, 1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hakonarson H, Maskeri N, Carter C, Hodinka RL, Campbell D, Grunstein MM. Mechanism of rhinovirus-induced changes in airway smooth muscle responsiveness. J Clin Invest 102: 1732–1741, 1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hirota S, Helli P, Janssen LJ. Ionic mechanisms and Ca2+ handling in airway smooth muscle. Eur Respir J 30: 114–133, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hirota S, Trimble N, Pertens E, Janssen LJ. Intracellular Cl- fluxes play a novel role in Ca2+ handling in airway smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 290: L1146–L1153, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jacob MK, White RE. Diazepam, gamma-aminobutyric acid, and progesterone open K(+) channels in myocytes from coronary arteries. Eur J Pharmacol 403: 209–219, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Janssen LJ, Sims SM. Acetylcholine activates non-selective cation and chloride conductances in canine and guinea-pig tracheal myocytes. J Physiol 453: 197–218, 1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johansson S, Druzin M, Haage D, Wang MD. The functional role of a bicuculline-sensitive Ca2+-activated K+ current in rat medial preoptic neurons. J Physiol 532: 625–635, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jones TR, Charette L, Garcia ML, Kaczorowski GJ. Interaction of iberiotoxin with β-adrenoceptor agonists and sodium nitroprusside on guinea pig trachea. J Appl Physiol 74: 1879–1884, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jones TR, Charette L, Garcia ML, Kaczorowski GJ. Selective inhibition of relaxation of guinea-pig trachea by charybdotoxin, a potent Ca(++)-activated K+ channel inhibitor. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 255: 697–706, 1990. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jooste E, Zhang Y, Emala CW. Rapacuronium preferentially antagonizes the function of M2 versus M3 muscarinic receptors in guinea pig airway smooth muscle. Anesthesiology 102: 117–124, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koh YY, Lee MH, Sun YH, Park Y, Kim CK. Improvement in bronchial hyperresponsiveness with inhaled corticosteroids in children with asthma: importance of family history of bronchial hyperresponsiveness. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 166: 340–345, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kotlikoff MI, Kamm KE. Molecular mechanisms of beta-adrenergic relaxation of airway smooth muscle. Annu Rev Physiol 58: 115–141, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kume H, Hall IP, Washabau RJ, Takagi K, Kotlikoff MI. Beta-adrenergic agonists regulate KCa channels in airway smooth muscle by cAMP-dependent and -independent mechanisms. J Clin Invest 93: 371–379, 1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kume H, Takai A, Tokuno H, Tomita T. Regulation of Ca2+-dependent K+-channel activity in tracheal myocytes by phosphorylation. Nature 341: 152–154, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McGraw DW, Elwing JM, Fogel KM, Wang WC, Glinka CB, Mihlbachler KA, Rothenberg ME, Liggett SB. Crosstalk between Gi and Gq/Gs pathways in airway smooth muscle regulates bronchial contractility and relaxation. J Clin Invest 117: 1391–1398, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mizuta K, Osawa Y, Xu D, Yi Zhang Y, Emala CW. GABAA Receptors are expressed and facilitate relaxation in airway smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 294: L1206–L1216, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moore CT, Wilson CG, Mayer CA, Acquah SS, Massari VJ, Haxhiu MA. A GABAergic inhibitory microcircuit controlling cholinergic outflow to the airways. J Appl Physiol 96: 260–270, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Muller T, Fritschy JM, Grosche J, Pratt GD, Mohler H, Kettenmann H. Developmental regulation of voltage-gated K+ channel and GABAA receptor expression in Bergmann glial cells. J Neurosci 14: 2503–2514, 1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nelson HS, Weiss ST, Bleecker ER, Yancey SW, Dorinsky PM. The Salmeterol Multicenter Asthma Research Trial: a comparison of usual pharmacotherapy for asthma or usual pharmacotherapy plus salmeterol. Chest 129: 15–26, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Olpe HR, Steinmann MW, Hall RG, Brugger F, Pozza MF. GABAA and GABAB receptors in locus coeruleus: effects of blockers. Eur J Pharmacol 149: 183–185, 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Osawa Y, Xu D, Sternberg D, Sonett JR, D'Armiento J, Panettieri RA, Emala CW. Functional expression of the GABAB receptor in human airway smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 291: L923–L931, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Robertson BE, Schubert R, Hescheler J, Nelson MT. cGMP-dependent protein kinase activates Ca-activated K channels in cerebral artery smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 265: C299–C303, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Salvail D, Dumoulin M, Rousseau E. Direct modulation of tracheal Cl–channel activity by 5,6- and 11,12-EET. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 275: L432–L441, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sayers I, Swan C, Hall IP. The effect of beta2-adrenoceptor agonists on phospholipase C (beta1) signalling in human airway smooth muscle cells. Eur J Pharmacol 531: 9–12, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Simeone TA, Donevan SD, Rho JM. Molecular biology and ontogeny of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptors in the mammalian central nervous system. J Child Neurol 18: 39–48, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith N, Browning CA, Duroudier N, Stewart C, Peel S, Swan C, Hall IP, Sayers I. Salmeterol and cytokines modulate inositol-phosphate signalling in human airway smooth muscle cells via regulation at the receptor locus. Respir Res 8: 68, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stein V, Nicoll RA. GABA generates excitement. Neuron 37: 375–378, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tanaka Y, Horinouchi T, Koike K. New insights into beta-adrenoceptors in smooth muscle: distribution of receptor subtypes and molecular mechanisms triggering muscle relaxation. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 32: 503–514, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tanaka Y, Yamashita Y, Yamaki F, Horinouchi T, Shigenobu K, Koike K. MaxiK channel mediates beta2-adrenoceptor-activated relaxation to isoprenaline through cAMP-dependent and -independent mechanisms in guinea-pig tracheal smooth muscle. J Smooth Muscle Res 39: 205–219, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tanaka Y, Yamashita Y, Yamaki F, Horinouchi T, Shigenobu K, Koike K. Evidence for a significant role of a Gs-triggered mechanism unrelated to the activation of adenylyl cyclase in the cyclic AMP-independent relaxant response of guinea-pig tracheal smooth muscle. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 368: 437–441, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tohda Y, Ohkawa K, Kubo H, Muraki M, Fukuoka M, Nakajima S. Role of GABA receptors in the bronchial response: studies in sensitized guinea-pigs. Clin Exp Allergy 28: 772–777, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Townley RG, Horiba M. Airway hyperresponsiveness: a story of mice and men and cytokines. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 24: 85–110, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van Schayck CP, Graafsma SJ, Visch MB, Dompeling E, van WC, van Herwaarden CL. Increased bronchial hyperresponsiveness after inhaling salbutamol during 1 year is not caused by subsensitization to salbutamol. J Allergy Clin Immunol 86: 793–800, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang YX, Kotlikoff MI. Muscarinic signaling pathway for calcium release and calcium-activated chloride current in smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 273: C509–C519, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xiang YY, Wang S, Liu M, Hirota JA, Li J, Ju W, Fan Y, Kelly MM, Ye B, Orser B, O'Byrne PM, Inman MD, Yang X, Lu WY. A GABAergic system in airway epithelium is essential for mucus overproduction in asthma. Nat Med 13: 862–867, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]