Abstract

Intermedin (IMD) is a newly discovered peptide related to calcitonin gene-related peptide and adrenomedullin, and has been shown to reduce blood pressure and reactive oxygen species formation in vivo. In this study, we determined whether IMD exerts vascular and renal protection in DOCA-salt hypertensive rats by intravenous injection of adenovirus harboring the human IMD gene. Expression of human IMD was detected in the rat kidney via immunohistochemistry. IMD administration significantly lowered blood pressure, increased urine volume, and restored creatinine clearance. IMD also dramatically decreased superoxide formation and media thickness in the aorta. Vascular injury in the kidney was reduced by IMD gene delivery as evidenced by the prevention of glomerular and peritubular capillary loss. Moreover, IMD lessened morphological damage of the renal tubulointerstitium and reduced glomerular injury and hypertrophy. Attenuation of inflammatory cell accumulation in the kidney by IMD was accompanied by inhibition of p38MAPK activation and intercellular adhesion molecule 1 expression. In addition, IMD gene transfer resulted in a marked decline in myofibroblast and collagen accumulation in association with decreased transforming growth factor-β1 levels. Furthermore, IMD increased nitric oxide excretion in the urine and lowered the amount of lipid peroxidation. These results demonstrate that IMD is a powerful renal protective agent with pleiotropic effects by preventing endothelial cell loss, kidney damage, inflammation, and fibrosis in hypertensive DOCA-salt rats via inhibition of oxidative stress and proinflammatory mediator pathways.

Keywords: gene therapy, inflammation, fibrosis

intermedin (IMD; also known as adrenomedullin-2) is a newly discovered peptide that belongs to the calcitonin/calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) family, which includes calcitonin, CGRP, amylin, and adrenomedullin (36, 40). IMD is distributed in a wide variety of tissues, including brain, heart, and kidney (29, 38, 40). Within the kidney, IMD is found in tubular cells of both the cortex and medulla, as well as endothelial cells of the glomerulus and vasa recta (39). Due to its expression in the hypothalamus, pituitary gland, and renal tubules, IMD is believed to be closely involved in the regulation of water-electrolyte balance and blood volume (1). Indeed, intravenous and intrarenal arterial infusion of IMD peptide in normotensive rats resulted in a decline in blood pressure and an increase in renal blood flow, urine flow, and sodium excretion in a dose-dependent manner (12, 13). IMD was also observed to have a vasodilatory effect in spontaneously hypertensive rats with high blood pressure (11). IMD elicits its biological actions via nonselective interaction with different combinations of calcitonin receptor-like receptor (CRLR) and the three receptor activity-modifying proteins (RAMPs) (36). Whereas CRLR is expressed ubiquitously in the body, RAMP1 and RAMP2 are detected predominately in the vasculature, and RAMP3 is mostly found in the kidney (20, 30, 33). Stimulation of CRLR/RAMP receptor complexes on the surface of endothelial cells elevates cAMP and nitric oxide (NO) formation and may provide a mechanism for IMD's actions on hypotension and vasodilation (1).

It has been recently proposed that chronic hypoxia in the tubulointerstitium is the final common pathway to end-stage renal disease (31). Severe tubulointerstitial damage is associated with peritubular capillary loss and rarefaction. Indeed, Iwazu et al. (17) demonstrated that peritubular capillary loss, which leads to a hypoxic environment, precedes the development of tubulointerstitial fibrosis in mineralocorticoid hypertensive rats. The deoxycorticosterone acetate (DOCA)-salt rat is an excellent model for the examination of vascular and renal injury in the hypertensive setting. The high blood pressure induced by DOCA-salt treatment leads to damage of the cardiovascular and renal systems, often characterized by endothelial dysfunction, kidney fibrosis, glomerulosclerosis, and renal hypertrophy (4, 32). Kidney damage in DOCA-salt rats is accompanied by a significant increase in the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), proinflammatory cytokines, and profibrotic factors (4, 17, 18, 42). In the present study, we evaluated the protective effect of human IMD gene delivery on DOCA-salt-induced oxidative stress, inflammation, fibrosis, and vascular injury.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Adenovirus preparation.

Adenovirus was generated using plasmids generously supplied by Dr. M. Kay (Stanford University) according to a method previously described (28). The plasmid DNA pShuttle was linearized by enzyme digestion at the SmaI site. A blunt-end CMV-IMD-pA fragment was obtained by excising the DNA from the pcDNA3.CMV-IMD-pA plasmid (graciously provided by S.-Y. T. Hsu, Stanford University) and ligated to the shuttle vector. The CMV-IMD-pA transcription unit was released from the shuttle vector by I-Ceu-I and PI-Sce-I sequentially. The shuttle insert was then ligated to the adenoviral genome backbone plasmid pAdHM4 cut with the same enzymes. The final construct, pAdHM4.CMV-IMD-4F2-pA, was digested by PacI to release the complete linear adenoviral DNA. The DNA was transiently transfected into 293 HEK cells using Effectene reagent (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer's direction. The resulting virus was serially passaged five times.

Animal treatment.

All procedures complied with the standards for care and use of animal subjects as stated in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (Institute of Laboratory Resources, National Academy of Sciences, Bethesda, MD). The protocol for our animal studies was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the Medical University of South Carolina. Left unilateral nephrectomy was performed on male Wistar rats (Harlan Sprague-Dawley, Indianapolis, IN) weighing 200–220 g. After surgery, experimental animals received weekly subcutaneous injections of DOCA (25 mg/kg body wt; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) suspended in sesame oil and were provided with 1% NaCl drinking water. Each rat was injected with a 200 μl solution containing 5 × 1011 plaque-forming units of either Ad.Null or Ad.IMD (n = 7 per group) one time via the tail vein 2 wk after the start of steroid/salt treatment. Rats in the sham group (n = 7) were subcutaneously injected with sesame oil and provided with tap water. Two weeks after gene transfer, rats were anesthetized with a ketamine/xylazine cocktail. Kidneys and aortas were removed for morphological, histological, and biochemical analyses.

Blood pressure measurement and blood and urine parameters.

Systolic blood pressure was measured by tail-cuff method as previously described (42). Serum was collected on the day of death by cardiac puncture. Twenty-four-hour urine was collected from rats in metabolic cages 2 days before death. To eliminate contamination of urine samples, animals received only water during the 24-h collection period. Blood urea nitrogen, serum creatinine, and creatinine clearance were calculated as previously described (5).

Morphological and histological analyses.

Kidneys and aortas were fixed in 4% formaldehyde, dehydrated, and paraffin-embedded. Four-micrometer-thick sections were subjected to hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), periodic acid-Schiff (PAS), silver, and Sirius red staining. Light microscopic morphological evaluation of glomeruli was conducted in a blinded fashion as previously reported (18). At least 30 glomeruli per section were examined for the evaluation of glomerular lesions and hypertrophy. The severity of glomerular injury (characterized by glomerulosclerosis, glomerular necrosis, fibroid necrosis, and/or proliferative glomerular lesions) and glomerular hypertrophy was calculated semiquantitatively using a 0 to 3 scale (0, normal or almost normal; 1, mild; 2, moderate; 3, severe) for each glomerulus in PAS-stained or silver-stained slides, respectively. Cortical areas of kidney sections stained with Sirius red were analyzed for collagen fraction volume with an image analysis system (13). Twenty fields without large vessels were randomly selected from each kidney section at a magnification of ×100. Collagen fraction volume was then calculated as percentage of stained area within a field using National Institutes of Health (NIH) image software. Aortic media thickness was measured by image analysis of H&E-stained sections at ×40 magnification. Three different areas of each aorta were measured and quantified using NIH image software, and the results were averaged (22).

Immunohistochemical staining and quantitative analysis.

Immunohistochemistry was performed using the Vectastain Universal Elite ABC Kit (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA), following the supplied instructions. Kidney sections from paraffin-embedded tissue were incubated at 4°C overnight with primary antibodies against the monocyte/macrophage marker ED-1 (Chemicon, Temecula, CA), α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA; Sigma), endothelial cell-specific marker JG-12 (kindly provided by D. Kerjaschki, University of Vienna), 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE) adducts (Oxis International, Foster City, CA), and human IMD (Peptide Institute, Osaka, Japan). For ICAM-1 immunohistochemistry, kidneys were placed in OCT embedding medium (Tissue-Tek, Torrance, CA), cryosectioned, and incubated with primary antibody for 1 h as described previously (16). After development, tissue sections were slightly counterstained with hematoxylin. The number of monocytes/macrophages within glomeruli was counted as positive staining for ED-1 in a blinded manner from 10 different fields of each section at ×200 magnification. Peritubular capillary rarefaction index was obtained from JG-12-stained slides by averaging the percentage of squares in 10 × 10 grids using at least 10 sequential fields at ×100 magnification as described previously (23). The minimum possible capillary rarefaction index is 0, and the maximum score is 100; the latter would indicate a complete absence of JG-12-positive cells. Glomerular capillaries were identified by JG-12-positive staining, and glomerular capillary density was calculated as the number of capillaries per mm2 using 15 glomeruli from each rat. JG-12 antibody was utilized for endothelial cell detection due to its low background and intense staining (21).

Measurement of superoxide in aorta.

Superoxide levels in aortas were determined by in situ and chemiluminescent methods (26, 37). Aortic ring segments to be examined for in situ superoxide production were immediately placed in OCT embedding medium at the time of death and stored at −80°C until analysis. Aortic ring segments were cut into 30-μm-thick sections and received topical application of the fluorescent dye hydroethidine (HE; 2 μM), which is oxidized to ethidium in the presence of superoxide to produce red fluorescence. Slides were incubated in a light-protected humidified chamber at 37°C for 30 min. Images were obtained with a laser-scanning confocal microscope equipped with a krypton/argon laser. For the measurement of superoxide production by lucigenin-enhanced chemiluminescence, ring segments were placed in a polypropylene tube containing 1 ml PBS and lucigenin (5 μM), and immediately placed in a TD20/20 luminometer (Turner Designs, Sunnyvale, CA). The relative light units (RLU) emitted were integrated for 8 min. Dark current readings (photomultiplier background signal) were automatically subtracted. Background counts were determined from identically treated vessel-free preparations and subtracted from the readings obtained with vessels. Dry weights were obtained for each vascular segment to allow normalization of activity.

Measurement of TGF-β1 and nitrate/nitrite levels.

Renal tissue was homogenized in lysis buffer (10 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 20 mM Na4P2O7, 2 mM Na3VO4, and 1% Triton X-100) containing 1:100 protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma). Total (latent and active) TGF-β1 protein levels in renal extracts were determined by ELISA (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). Nitrate/nitrite levels (indicative of NO formation) in urine were measured by a fluorometric assay as previously described (27).

Western blot analysis.

Western blot analysis was performed using the cytosolic fraction of kidney extracts. Primary antibodies were used to detect 4-HNE protein adducts (Oxis International), with β-actin serving as a control, as well as total and phosphorylated forms of p38MAPK (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA). PVDF membranes were incubated with secondary antibody conjugated to LumiGLO chemiluminescent reagent. Chemiluminescence was detected using an ECL-Plus kit (Perkin Elmer Life Science, Boston, MA).

Statistical analysis.

Data were analyzed using standard statistical methods and ANOVA followed by Fisher's PLSD and Bonferroni post hoc tests where appropriate. Group data are expressed as means ± SE. Values of all parameters were considered significantly different at a value of P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Expression of human IMD after adenovirus injection.

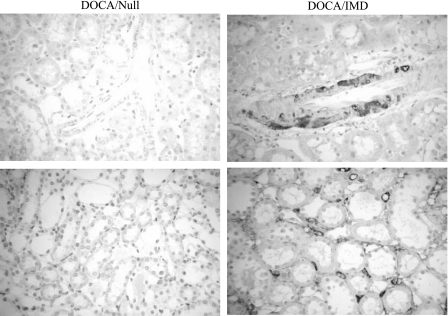

Human IMD was detected in the kidney by immunohistochemistry in rats injected with adenovirus carrying the human IMD gene (Fig. 1). Positive human IMD immunostaining was identified in large blood vessels, capillaries, tubular cells, and interstitial cells of the kidney. Human IMD protein expression was not detected in control rats injected with Ad.Null.

Fig. 1.

Human intermedin (IMD) was identified in kidneys of DOCA-salt rats injected with Ad.IMD, but not with Ad.Null, by immunohistochemical staining with anti-human IMD antibody. Representative images of renal artery (top) and tubulointerstitium (bottom). Original magnification is ×200.

Effect of IMD gene transfer on blood pressure and renal function in DOCA-salt rats.

IMD gene delivery significantly reduced systolic blood pressure compared with rats receiving Ad.Null 1 wk after virus injection (Table 1). In addition, creatinine clearance was reduced in the DOCA/Null group, but restored in the animals receiving Ad.IMD. DOCA/Null rats had a higher urine volume compared with sham, and IMD gene delivery further increased this parameter twofold, indicating that IMD is a powerful diuretic. However, the increase in blood urea nitrogen and serum creatinine levels after 4 wk of DOCA-salt treatment was unaffected by IMD administration.

Table 1.

Blood pressure and renal function parameters

| Sham | DOCA/Null | DOCA/IMD | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Systolic BP, mmHg | 114±6.2 | 173±7.5 | 154±9.1* |

| CCr, ml·min−1·100 g body wt−1 | 0.19±0.01 | 0.13±0.01 | 0.19±0.02* |

| UV, ml·day−1·100 g body wt−1 | 4±1.2 | 30±5.2 | 62±17.8* |

| Blood urea nitrogen, mg/dl | 27±1.2 | 35±5.1 | 31±1.8 |

| Serum creatinine, mg/dl | 0.57±0.05 | 0.67±0.05 | 0.65±0.03 |

Values are expressed as means ± SE (n = 5–6). IMD, intermedin; BP, blood pressure; CCr, creatinine clearance; UV, urine volume.

P < 0.05 vs. DOCA/Null.

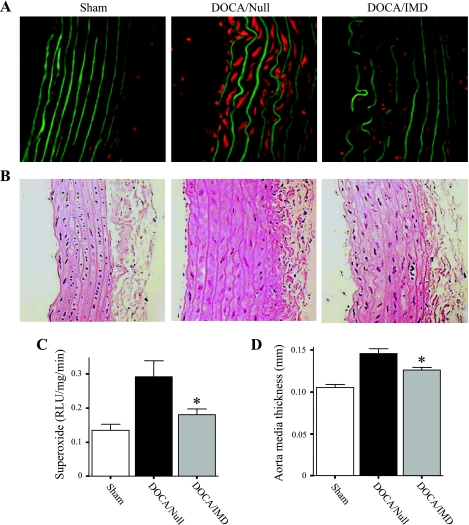

IMD gene delivery reduces aortic in situ superoxide production and media thickness.

Superoxide production was dramatically increased in aortas of DOCA-salt rats receiving Ad.Null compared with sham, as determined by in situ fluorescence of HE (Fig. 2A). This was confirmed by measurement of superoxide levels in aortic segments using lucigenin-based chemiluminescence (Fig. 2C). The results from both methods indicated that IMD significantly decreased superoxide levels compared with DOCA/Null animals. In addition, thoracic aorta media thickness of DOCA-salt rats injected with Ad.Null was found to be significantly increased compared with sham rats, but was inhibited by IMD gene delivery (Fig. 2, B and D).

Fig. 2.

IMD gene delivery decreases aortic superoxide levels and media thickness in DOCA-salt rats. A: detection of superoxide in rat aortas by in situ oxidation of the fluorescent dye hydroethidine (HE). Red fluorescence indicates oxidation of HE to ethidium; green fluorescence represents aortic elastin fibers. Original magnification is ×200. B: representative images of aortas stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) to evaluate and measure aortic media thickness. Original magnification is ×200. C: measurement of superoxide in aortic ring segments by lucigenin-enhanced chemiluminescence. RLU, relative light units. D: calculation of media thickness. *P < 0.05 vs. DOCA/Null. Values are expressed as means ± SE (n = 6).

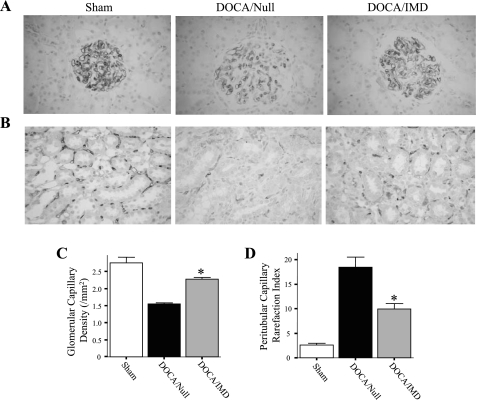

IMD gene transfer prevents glomerular and peritubular capillary loss.

Immunohistochemical staining against JG-12 (an endothelial cell marker) was performed to examine the effect of DOCA-salt treatment on endothelial cell loss in the kidney. Rats in the DOCA/Null group had a markedly lower amount of capillaries in glomeruli compared with sham, but IMD gene transfer attenuated this effect (Fig. 3, A and C). Furthermore, rats injected with Ad.IMD were observed to have reduced capillary rarefaction in the outer stripe of the medulla compared with rats receiving Ad.Null (Fig. 3B); quantitative analysis confirmed this result (Fig. 3D). Prevention of endothelial cell loss in glomeruli and the tubulointerstitium by IMD may be attributed to its anti-oxidant activity in the vasculature.

Fig. 3.

IMD gene delivery prevents renal glomerular and outer medullary capillary loss in DOCA-salt rats. Representative images of glomeruli (A) and the outer medulla of kidney (B) sections subjected to immunohistochemical staining with JG-12 antibody. Original magnification is ×200. C: quantitation of glomerular capillary density. D: rarefaction index of peritubular capillaries of the outer medulla. *P < 0.05 vs. DOCA/Null. Values are expressed as means ± SE (n = 5–6).

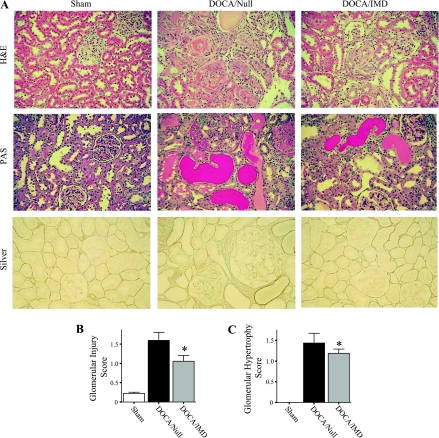

IMD gene delivery protects against renal histological damage.

The severity of kidney injury was investigated by examination of H&E-, PAS-, and silver-stained slides. DOCA-salt treatment resulted in substantial damage to kidneys in the Ad.Null group, as indicated by glomerular necrosis, sclerosis and hypertrophy, fibrinoid necrosis of arteries, protein casts, and cellular debris within tubular lumens (Fig. 4A). Compared with the DOCA/Null group, rats receiving Ad.IMD had considerably less glomerular and tubulointerstitial lesions. Semiquantitative analysis of glomerular injury and hypertrophy by a scoring method verified these results (Fig. 4, B and C). Kidneys of rats in the sham group were normal in appearance.

Fig. 4.

IMD gene transfer reduces morphological damage of kidneys in DOCA-salt rats. A: representative images of kidney sections subjected to H&E, PAS, and silver histological staining. Original magnification is ×200. Glomerular injury score (B) and glomerular hypertrophy score (C). *P < 0.05 vs. DOCA/Null. Values are expressed as means ± SE (n = 5–6).

IMD gene delivery ameliorates renal inflammation and fibrosis.

To assess the effect of IMD on inflammation in the kidney, renal sections underwent immunohistochemical staining for several inflammatory markers. DOCA-salt treatment caused a marked elevation of ED-1-positive cells in the interstitium and glomeruli of the kidney, but IMD gene delivery significantly attenuated this effect; the amount of ED-1-positive cells in the sham group was negligible (Fig. 5A). The number of monocytes/macrophages within glomeruli was counted to confirm this observation (Fig. 5B). In addition, intense staining of ICAM-1 was observed in the tubulointerstitium, glomeruli, and around blood vessels of the DOCA/Null group, but dramatically reduced in rats injected with the IMD gene (Fig. 5A). Western blot analysis indicated that DOCA-salt treatment increased phosphorylation of p38MAPK, but the effect was attenuated by IMD gene delivery (Fig. 5C).

Fig. 5.

IMD gene delivery inhibits renal monocyte/macrophage accumulation and ICAM-1 protein expression in DOCA-salt rats. A: representative images of kidney sections subjected to immunohistochemical staining with ED-1 and ICAM-1 antibodies. Original magnification is ×200. B: quantitation of monocytes/macrophages detected in glomeruli. C: Western blot and densitometric analysis of phosphorylated and total p38MAPK in renal extracts. *P < 0.05 vs. DOCA/Null. Values are expressed as means ± SE (n = 5–6).

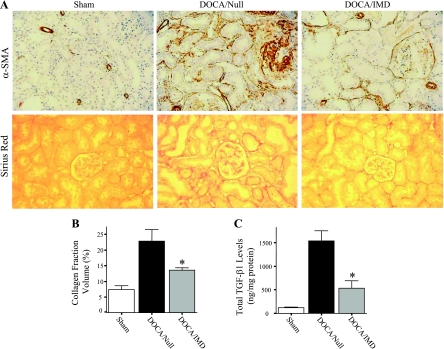

Kidney sections were immunostained for α-SMA to detect the presence of myofibroblasts and/or activated fibroblasts, cells that are characterized by the synthesis of large amounts of collagen and other extracellular matrix proteins. Whereas significant expression of α-SMA was detected in glomeruli and the tubulointerstitium of DOCA/Null rats, considerably less staining was found in the DOCA/IMD group (Fig. 6A); as expected, smooth muscle layers of blood vessels were positive for α-SMA. As determined by Sirius red staining, significant collagen accumulation was observed in glomeruli and the tubulointerstitial space of rats receiving Ad.Null, but was dramatically reduced in the DOCA/IMD group; minimal collagen staining was detected in sham rats (Fig. 6A). Collagen fraction volume was calculated to confirm this result (Fig. 6B). Moreover, DOCA-salt treatment caused a marked increase in total protein levels of the profibrotic cytokine TGF-β1, but was notably diminished by IMD gene delivery (Fig. 6C).

Fig. 6.

IMD gene transfer decreases renal myofibroblast and collagen accumulation and transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1) levels. A: representative images of kidney sections subjected to immunohistochemical staining with α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) antibody and Sirius red histological staining. Original magnification is ×200. B: collagen fraction volume in the kidney. C: total renal TGF-β1 levels as determined by ELISA. *P < 0.05 vs. DOCA/Null. Values are expressed as means ± SE (n = 5–6).

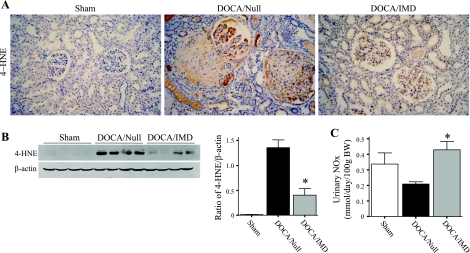

IMD gene transfer reduces 4-HNE adduct formation and increases nitrate/nitrite levels.

Immunostaining of the oxidative lipid 4-HNE showed that 4-HNE adducts were mainly found in injured glomeruli and vessels of the DOCA/Null group, whereas administration of IMD attenuated positive staining (Fig. 7A). In addition, Western blot for 4-HNE indicated that the intensity of a 37-kDa band was significantly increased in the DOCA/Null compared with sham, but was dramatically diminished upon IMD gene transfer (Fig. 7B). Therefore, while IMD decreased aortic superoxide formation, IMD similarly reduced renal lipid peroxidation. These results indicate an anti-oxidant action of IMD in the DOCA-salt rat. As NO is known to antagonize ROS formation, we measured nitrate/nitrite (NOx) content in urine samples. Urinary NOx levels were decreased approximately twofold in DOCA/Null rats compared with the sham group, but IMD gene transfer restored NOx excretion (Fig. 7C).

Fig. 7.

IMD gene delivery reduces renal 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE) adducts and increases nitrate/nitrite (NOx) excretion. A: representative images of kidney sections subjected to immunohistochemical staining with 4-HNE adduct antibody. Original magnification is ×200. B: Western blot and densitometric analysis of 4-HNE adducts in renal extracts; the 37-kDa band is shown. C: urinary NOx levels from urine collected 2 days before death. *P < 0.05 vs. DOCA/Null. Values are expressed as means ± SE (n = 5–6).

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrates, for the first time, that IMD via gene delivery offers a broad protective role against renal and vascular damage in a setting of malignant hypertension and its sequelae. Renal expression of human IMD after adenovirus-mediated gene transfer caused significant prevention of capillary loss, in addition to reduction of tubulointerstitial and glomerular injury, inflammation, and extracellular matrix deposition. These effects occurred in conjunction with increased NO excretion and inhibition of lipid peroxidation as well as proinflammatory and profibrotic factor expression in the kidney. Collectively, these findings indicate that IMD administration can inhibit oxidative stress in the blood vessel and kidney, and thus protect against vascular injury, renal inflammation, and fibrosis in the DOCA-salt hypertensive rat.

Tubulointerstitial damage can be a result of hypertension, development of oxidative stress, and elevation of vasoconstrictive substances, all of which are evident in the DOCA-salt animal model. It has been previously demonstrated that IMD administration induces a hypotensive response in both normotensive and hypertensive rats (11–13). Although we found IMD to decrease blood pressure in DOCA-salt rats, accompanied by a potent diuretic action, it is possible that reduction of blood pressure alone is not solely responsible for the renal protective effects observed. Indeed, Dworkin et al. (10) reported that blood pressure decline offered no histological protection in DOCA-salt hypertensive rats. Furthermore, a recent study showed that suppression of NF-κB activity was found to be protective against renal inflammation and fibrosis with no effect on the development of hypertension (16). Therefore, it is highly likely that IMD has some organ protective actions independent of blood pressure reduction.

Augmented renal and vascular ROS formation has been identified in mineralocorticoid hypertensive rats, as well as other animal models of hypertension, and may contribute to kidney damage, inflammation, and increased NF-κB activity (2, 3, 18, 24). In DOCA-salt rats, elevated p22phox expression and NADH oxidase activity have been shown to be responsible for the rise in aortic superoxide production (2, 41). This increase in ROS levels can promote vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation, consequently leading to arterial media thickness (9, 14). In the current study, we found that IMD had the ability to lower superoxide content in the aorta and thus alleviate aortic blood vessel stiffening. Moreover, we detected reduced lipid peroxidation (a marker of oxidative stress) in the kidney and increased urinary NO excretion in DOCA-salt rats receiving the IMD gene. Previous studies reported that IMD can stimulate the NOS/NO pathway in rat aortas as well as reduce oxidative stress and improve cell viability in cultured endothelial cells in association with NO formation (7, 43). Taken together, the data suggest that the anti-oxidant property of IMD is mediated by NO. Since oxidative stress has a profound effect on endothelial cell apoptosis and the development of renal inflammation and fibrosis, attenuation of ROS formation by IMD through NO formation could therefore play a protective role against capillary loss and chronic kidney disease.

It was recently demonstrated that peritubular capillary rarefaction precedes the development of renal fibrosis in DOCA-salt rats (17). The deficiency of peritubular and glomerular capillaries subjects the kidney to a hypoxic environment. The low oxygen setting in turn provokes tubular cell apoptosis and epithelial-mesenchymal transition, thus contributing to renal tissue damage, inflammation, and fibrosis. In the present study, severe renal morphological injury was evident in DOCA-salt rats receiving empty virus injection, as indicated by glomerular sclerosis, glomerular hypertrophy, inflammatory cell infiltration, fibrosis, and renal capillary loss. IMD gene delivery prevented glomerular capillary loss and reduced capillary rarefaction in the outer medulla, a region of the kidney that is particularly prone to hypoxic stress (35). In addition, IMD caused a marked attenuation of renal interstitial and glomerular damage, inflammation, myofibroblast accumulation, and extracellular matrix deposition.

Vascular inflammation and injury appear to have a vital role in contributing to kidney damage, as Henke et al. (16) showed that suppression of NF-κB in the endothelium modulates renal inflammation and fibrosis. NF-κB is a transcription factor that, when activated, triggers upregulation of proinflammatory gene expression (15, 25). It has been found that p38MAPK is required for NF-κB-dependent gene transcription and is essential in mediating the inflammatory response (6, 34). One of the target genes of NF-κB is ICAM-1, a cell adhesion molecule that recruits inflammatory cells to sites of tissue damage. In our study, we observed significant monocyte/macrophage accumulation in the kidney as well as intense immunostaining of ICAM-1 in glomeruli and throughout the tubulointerstitium of DOCA-salt-treated rats. These findings were associated with an increase in phosphorylation of p38MAPK. IMD gene delivery, however, significantly inhibited p38MAPK phosphorylation, ICAM-1 expression, and inflammatory cell infiltration, indicating that IMD has a protective role against renal inflammation in the DOCA-salt rat model of kidney injury.

The inhibition of inflammation by IMD may lead to the prevention of renal fibrosis since macrophages produce profibrotic molecules, such as TGF-β1. TGF-β1 can also be generated from proximal tubular cells via direct cell contact between monocytes and ICAM-1 expressed on the tubular cell surface (45). This increase in renal TGF-β1 levels can result in the formation and accumulation of α-SMA-positive myofibroblasts via epithelial-mesenchymal transition and/or fibroblast activation (19). In our study, a large population of myofibroblasts was present in DOCA-salt rats. This observation corresponded with a significant increase in collagen fraction volume and TGF-β1 levels in the kidney. However, gene transfer of IMD remarkably diminished these effects. It is possible that the reduction of the fibrotic response of DOCA-salt treatment by IMD is due to IMD's capacity to increase NO bioavailability, as NO has been reported to inhibit TGF-β1 expression in kidney cells (8, 44). Moreover, since TGF-β1 is strongly upregulated by ROS, the reduction in oxidative stress by IMD could prevent the synthesis of TGF-β1.

In conclusion, this study elucidates an important protective role for IMD in the prevention of hypertension-induced renal and vascular injury. Further investigation of the properties of this peptide could reveal considerable therapeutic value for IMD in organ disease treatment.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants HL-29373 and DK-066350, and C06 RR-015455 from the Extramural Research Facilities Program of the National Center for Research Resources.

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. The article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bell D, McDermott BJ. Intermedin (adrenomedullin-2): a novel counterregulatory peptide in the cardiovascular and renal systems. Br J Pharmacol 153, Suppl 1: S247–S262, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beswick RA, Dorrance AM, Leite R, Webb RC. NADH/NADPH oxidase and enhanced superoxide production in the mineralocorticoid hypertensive rat. Hypertension 38: 1107–1111, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beswick RA, Zhang H, Marable D, Catravas JD, Hill WD, Webb RC. Long-term antioxidant administration attenuates mineralocorticoid hypertension and renal inflammatory response. Hypertension 37: 781–786, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blasi ER, Rocha R, Rudolph AE, Blomme EA, Polly ML, McMahon EG. Aldosterone/salt induces renal inflammation and fibrosis in hypertensive rats. Kidney Int 63: 1791–1800, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bledsoe G, Crickman S, Mao J, Xia CF, Murakami H, Chao L, Chao J. Kallikrein/kinin protects against gentamicin-induced nephrotoxicity by inhibition of inflammation and apoptosis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 21: 624–633, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carter AB, Knudtson KL, Monick MM, Hunninghake GW. The p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase is required for NF-kappaB-dependent gene expression. The role of TATA-binding protein (TBP). J Biol Chem 274: 30858–30863, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen L, Kis B, Hashimoto H, Busija DW, Takei Y, Yamashita H, Ueta Y. Adrenomedullin 2 protects rat cerebral endothelial cells from oxidative damage in vitro. Brain Res 1086: 42–49, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Craven PA, Studer RK, Felder J, Phillips S, DeRubertis FR. Nitric oxide inhibition of transforming growth factor-beta and collagen synthesis in mesangial cells. Diabetes 46: 671–681, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deng LY, Schiffrin EL. Effects of endothelin on resistance arteries of DOCA-salt hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 262: H1782–H1787, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dworkin LD, Feiner HD, Randazzo J. Glomerular hypertension and injury in desoxycorticosterone-salt rats on antihypertensive therapy. Kidney Int 31: 718–724, 1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fujisawa Y, Nagai Y, Miyatake A, Miura K, Nishiyama A, Kimura S, Abe Y. Effects of adrenomedullin 2 on regional hemodynamics in conscious rats. Eur J Pharmacol 558: 128–132, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fujisawa Y, Nagai Y, Miyatake A, Miura K, Shokoji T, Nishiyama A, Kimura S, Abe Y. Roles of adrenomedullin 2 in regulating the cardiovascular and sympathetic nervous systems in conscious rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 290: H1120–H1127, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fujisawa Y, Nagai Y, Miyatake A, Takei Y, Miura K, Shoukouji T, Nishiyama A, Kimura S, Abe Y. Renal effects of a new member of adrenomedullin family, adrenomedullin2, in rats. Eur J Pharmacol 497: 75–80, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gallagher DL, Betteridge LJ, Patel MK, Schachter M. Effect of oxidants on vascular smooth muscle proliferation. Biochem Soc Trans 21: 98S, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guijarro C, Egido J. Transcription factor-kappa B (NF-kappa B) and renal disease. Kidney Int 59: 415–424, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Henke N, Schmidt-Ullrich R, Dechend R, Park JK, Qadri F, Wellner M, Obst M, Gross V, Dietz R, Luft FC, Scheidereit C, Muller DN. Vascular endothelial cell-specific NF-kappaB suppression attenuates hypertension-induced renal damage. Circ Res 101: 268–276, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Iwazu Y, Muto S, Fujisawa G, Nakazawa E, Okada K, Ishibashi S, Kusano E. Spironolactone suppresses peritubular capillary loss and prevents deoxycorticosterone acetate/salt-induced tubulointerstitial fibrosis. Hypertension 51: 749–754, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jin L, Beswick RA, Yamamoto T, Palmer T, Taylor TA, Pollock JS, Pollock DM, Brands MW, Webb RC. Increased reactive oxygen species contributes to kidney injury in mineralocorticoid hypertensive rats. J Physiol Pharmacol 57: 343–357, 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kalluri R, Neilson EG. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition and its implications for fibrosis. J Clin Invest 112: 1776–1784, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kamitani S, Asakawa M, Shimekake Y, Kuwasako K, Nakahara K, Sakata T. The RAMP2/CRLR complex is a functional adrenomedullin receptor in human endothelial and vascular smooth muscle cells. FEBS Lett 448: 111–114, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim YG, Suga SI, Kang DH, Jefferson JA, Mazzali M, Gordon KL, Matsui K, Breiteneder-Geleff S, Shankland SJ, Hughes J, Kerjaschki D, Schreiner GF, Johnson RJ. Vascular endothelial growth factor accelerates renal recovery in experimental thrombotic microangiopathy. Kidney Int 58: 2390–2399, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Loch D, Levick S, Hoey A, Brown L. Rosuvastatin attenuates hypertension-induced cardiovascular remodeling without affecting blood pressure in DOCA-salt hypertensive rats. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 47: 396–404, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Long DA, Mu W, Price KL, Roncal C, Schreiner GF, Woolf AS, Johnson RJ. Vascular endothelial growth factor administration does not improve microvascular disease in the salt-dependent phase of postangiotensin II hypertension. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 291: F1248–F1254, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Manning RD, Meng S, Tian N. Renal and vascular oxidative stress and salt sensitivity of arterial pressure. Acta Physiol Scand 179: 243–250, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.May MJ, Ghosh S. Signal transduction through NF-kappa B. Immunol Today 19: 80–88, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miller FJ, Gutterman DD, Rios CD, Heistad DD, Davidson BL. Superoxide production in vascular smooth muscle contributes to oxidative stress and impaired relaxation in atherosclerosis. Circ Res 82: 1298–1305, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Misko TP, Schilling RJ, Salvemini D, Moore WM, Currie MG. A fluorometric assay for the measurement of nitrite in biological samples. Anal Biochem 214: 11–16, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mizuguchi H, Kay MA. Efficient construction of a recombinant adenovirus vector by an improved in vitro ligation method. Hum Gene Ther 9: 2577–2583, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morimoto R, Satoh F, Murakami O, Totsune K, Suzuki T, Sasano H, Ito S, Takahashi K. Expression of adrenomedullin2/intermedin in human brain, heart, and kidney. Peptides 28: 1095–1103, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nagae T, Mukoyama M, Sugawara A, Mori K, Yahata K, Kasahara M, Suganami T, Makino H, Fujinaga Y, Yoshioka T, Tanaka I, Nakao K. Rat receptor activity-modifying proteins (RAMPs) for adrenomedullin/CGRP receptor: cloning and upregulation in obstructive nephropathy. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 270: 89–93, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nangaku M Chronic hypoxia and tubulointerstitial injury: a final common pathway to end-stage renal failure. J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 17–25, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nishiyama A, Yao L, Nagai Y, Miyata K, Yoshizumi M, Kagami S, Kondo S, Kiyomoto H, Shokoji T, Kimura S, Kohno M, Abe Y. Possible contributions of reactive oxygen species and mitogen-activated protein kinase to renal injury in aldosterone/salt-induced hypertensive rats. Hypertension 43: 841–848, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oliver KR, Wainwright A, Edvinsson L, Pickard JD, Hill RG. Immunohistochemical localization of calcitonin receptor-like receptor and receptor activity-modifying proteins in the human cerebral vasculature. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 22: 620–629, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ono K, Han J. The p38 signal transduction pathway: activation and function. Cell Signal 12: 1–13, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rabelink TJ, Wijewickrama DC, de Koning EJ. Peritubular endothelium: the Achilles heel of the kidney? Kidney Int 72: 926–930, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roh J, Chang CL, Bhalla A, Klein C, Hsu SY. Intermedin is a calcitonin/calcitonin gene-related peptide family peptide acting through the calcitonin receptor-like receptor/receptor activity-modifying protein receptor complexes. J Biol Chem 279: 7264–7274, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Skatchkov MP, Sperling D, Hink U, Mulsch A, Harrison DG, Sindermann I, Meinertz T, Munzel T. Validation of lucigenin as a chemiluminescent probe to monitor vascular superoxide as well as basal vascular nitric oxide production. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 254: 319–324, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Takahashi K, Kikuchi K, Maruyama Y, Urabe T, Nakajima K, Sasano H, Imai Y, Murakami O, Totsune K. Immunocytochemical localization of adrenomedullin 2/intermedin-like immunoreactivity in human hypothalamus, heart and kidney. Peptides 27: 1383–1389, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Takei Y, Hyodo S, Katafuchi T, Minamino N. Novel fish-derived adrenomedullin in mammals: structure and possible function. Peptides 25: 1643–1656, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Takei Y, Inoue K, Ogoshi M, Kawahara T, Bannai H, Miyano S. Identification of novel adrenomedullin in mammals: a potent cardiovascular and renal regulator. FEBS Lett 556: 53–58, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wu R, Millette E, Wu L, de Champlain J. Enhanced superoxide anion formation in vascular tissues from spontaneously hypertensive and desoxycorticosterone acetate-salt hypertensive rats. J Hypertens 19: 741–748, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xia CF, Bledsoe G, Chao L, Chao J. Kallikrein gene transfer reduces renal fibrosis, hypertrophy, and proliferation in DOCA-salt hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 289: F622–F631, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yang JH, Pan CS, Jia YX, Zhang J, Zhao J, Pang YZ, Yang J, Tang CS, Qi YF. Intermedin1–53 activates l-arginine/nitric oxide synthase/nitric oxide pathway in rat aortas. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 341: 567–572, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ying WZ, Sanders PW. The interrelationship between TGF-β1 and nitric oxide is altered in salt-sensitive hypertension. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 285: F902–F908, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang XL, Selbi W, de la Motte C, Hascall V, Phillips A. Renal proximal tubular epithelial cell transforming growth factor-β1 generation and monocyte binding. Am J Pathol 165: 763–773, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]