Abstract

We analyzed the effect of conditional, αMHC-dependent genetic β-catenin depletion and stabilization on cardiac remodeling following experimental infarct. β-Catenin depletion significantly improved 4-week survival and left ventricular (LV) function (fractional shortening: CTΔex3–6: 24 ± 1.9%; β-catΔex3–6: 30.2 ± 1.6%, P < 0.001). β-Catenin stabilization had opposite effects. No significant changes in adult cardiomyocyte survival or hypertrophy were observed in either transgenic line. Associated with the functional improvement, LV scar cellularity was altered: β-catenin-depleted mice showed a marked subendocardial and subepicardial layer of small cTnTpos cardiomyocytes associated with increased expression of cardiac lineage markers Tbx5 and GATA4. Using a Cre-dependent lacZ reporter gene, we identified a noncardiomyocyte cell population affected by αMHC-driven gene recombination localized to these tissue compartments at baseline. These cells were found to be cardiac progenitor cells since they coexpressed markers of proliferation (Ki67) and the cardiomyocyte lineage (αMHC, GATA4, Tbx5) but not cardiac Troponin T (cTnT). The cell population overlaps in part with both the previously described c-kitpos and stem cell antigen-1 (Sca-1)pos precursor cell population but not with the Islet-1pos precursor cell pool. An in vitro coculture assay of highly enriched (>95%) Sca-1pos cardiac precursor cells from β-catenin-depleted mice compared to cells isolated from control littermate demonstrated increased differentiation toward α-actinpos and cTnTpos cardiomyocytes after 10 days (CTΔex3–6: 38.0 ± 1.0% α-actinpos; β-catΔex3–6: 49.9 ± 2.4% α-actinpos, P < 0.001). We conclude that β-catenin depletion attenuates postinfarct LV remodeling in part through increased differentiation of GATA4pos/Sca-1pos resident cardiac progenitor cells.

Despite adaptive mechanisms including activation of cardiomyocyte survival pathways and hypertrophy, left ventricular (LV) remodeling often progresses to cardiac dilation and heart failure (1). Recently, the quantitative contribution of endogenous cardiac regeneration was found to account for at least 25% of cardiomyocytes in the infarct border zone (2). However, essential characteristics of this cardiac precursor cell pool, like signaling pathways directing differentiation and/or proliferation, are largely unknown.

Transcription factors essential for embryonic cardiac development also affect adult cardiac remodeling in mice (3). Regulation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway differentially regulates embryonic cardiac progenitor cells prespecification, renewal, and differentiation in the cardiac mesoderm (4–7). Activation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway specifically stimulates Islet-1 cardiac progenitor cells proliferation while delaying differentiation. Conversely, increased expression of Wnt signaling inhibitors in αMHCpos cardiac precursor cells isolated from embryoid bodies lead to increased cardiomyocyte differentiation (8).

We previously reported that downregulation of β-catenin in adult heart is required for adaptive hypertrophy upon chronic angiotensin II challenge (9). Here, we describe the effect of β-catenin depletion on ischemic LV-remodeling. We used two transgenic mouse models to study the effect of conditional depletion (β-catΔex3–6) or stabilization (β-catΔex3) of β-catenin upon αMHC-driven gene recombination in the adult heart (9). To monitor recombined cells we used the ROSA26 (lacZ) reporter mice (10). Our analysis revealed a specific subpopulation of cardiac progenitor cells including Sca-1pos and c-kitpos cells to be affected by αMHC-dependent gene recombination. In association with the functional improvement after infarct in β-catenin-depleted mice, isolated Sca-1pos cardiac precursor cells exhibited enhanced cell differentiation toward mature cardiomyocytes. In Vivo, early cardiac transcription factors GATA4 and Tbx5 were upregulated upon β-catenin depletion in infarcted mice. These data suggest β-catenin depletion to be beneficial in postinfarct LV remodeling in part through enhanced differentiation of αMHCpos cardiac resident progenitor cells.

Results

αMHC-Restricted β-Catenin Depletion or Stabilization Plus lacZ Reporter Gene Expression in Mice.

Mice with conditional β-catenin depletion (β-catΔex3–6) or stabilization (β-catΔex3) depending on αMHC-CrePR1 recombination in adult myocardium were generated as described before (9). Creneg littermate mice were used as controls and termed CTΔex3–6 or CTΔex3, respectively.

To monitor cells affected by αMHC-directed recombination, ROSA26 reporter mice were bred to β-catΔex3–6 resulting in β-catΔex3–6/lacZ mice expressing the lacZ gene in recombined cells. Cre-mediated conditional recombination was induced by mifepristone (RU-486) injection [Fig. S1A and see supporting information (SI) Text)]. Using the indicated primers (blue arrows in S1A), successful genomic recombination was confirmed (Fig. S1B). Depletion of the full-length β-catenin protein and expression of the β-galactosidase (β-gal) reporter were detected by immunofluorescence and Western blot in adult cardiomyocytes (Fig. S1C and S2A). Decreased expression of β-catenin (*, P < 0.05) and its target genes LEF1 (*, P < 0.05) and TCF4 (**, P < 0.01) was confirmed by quantitative real time-PCR 3 weeks after Cre induction (CTΔex3–6 n = 6; β-catΔex3–6 n = 15; Fig. S1D).

The same strategy was used to obtain mice with αMHC-restricted β-catenin stabilization (9). Excision of exon 3 containing the GSK3β phosphorylation site blocks proteasome-mediated degradation and results in cytoplasmic accumulation of β-catenin (11). The truncated β-catenin product was detected by PCR and Western blot (Fig. S1E and Fig. S2B), indicating successful recombination. The β-catenin target genes LEF1, TCF4, and Axin2 were upregulated as demonstrated by real-time PCR (data not shown) (9).

β-Catenin Depletion Attenuates Left Ventricular Remodeling After Myocardial Infarction.

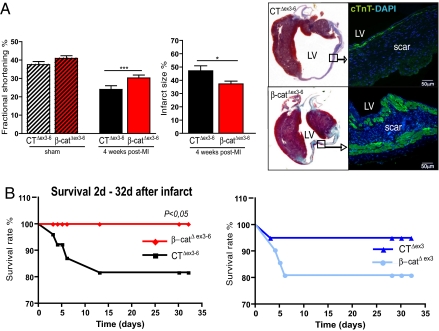

To determine whether β-catenin modulates ischemic cardiac remodeling, β-catenin depleted, stabilized, and respective control littermates were subjected to chronic ligation of the left anterior descendant coronary artery (LAD) (Fig. S3A). Mice who died within 2 days of the surgery or had no clear infarct scar in echocardiography and histology were excluded from further analysis (Fig. S3B and S4). At 4 weeks, β-catenin-depleted animals exhibited improved fractional shortening (Fig. 1A, CTΔex3–6 n = 7: 24.0 ± 1.9% vs. β-catΔex3–6 n = 13: 30.2 ± 1.6% ***, P < 0.001) and reduced heart weight/body weight ratio (HW/BW) (CTΔex3–6: 6.1 ± 0.42 vs. β-catΔex3–6: 5.3 ± 0.21 *, P < 0.05) (Table S1). In addition, infarct size was significantly reduced in β-catenin-depleted mice vs. controls (CTΔex3–6 n = 6: 47.2 ± 3.7% vs. β-catΔex3–6 n = 6: 37.2 ± 2.1% *, P < 0.05) (Fig. 1A and Fig. S3C). β-Catenin depletion also led to reduced mRNA expression of heart failure markers ANP and BNP at two weeks (CTΔex3–6 n = 5; β-catΔex3–6 n = 15, Fig. S6A).

Fig. 1.

αMHC-dependent β-catenin depletion attenuates postinfarct LV remodeling. (A) β-Catenin depletion results in improved fractional shortening and reduced infarct size 4 weeks after infarct associated with a prominent subendocardial and subepicardial layer of cardiomyocytes as identified by cTnT staining. (B) Kaplan-Meier survival curve demonstrated significantly enhanced survival in β-catΔex3–6 mice compared to CTΔex3–6 mice 4 weeks following experimental infarct. In contrast, increased mortality was observed in β-catΔex3 mice compared to CTΔex3 mice. CTΔex3–6 n = 11; β-catΔex3–6 n = 15; CTΔex3 n = 8; β-catΔex3 n = 9; MI, myocardial infarct; LV, left ventricle; cTnT, cardiac Troponin T; *, P < 0.05.

Mice with β-catenin stabilization displayed no major differences compared to controls in infarct size or LV function (Fig. S5). β-Catenin depletion significantly decreased mortality over the first 4 weeks after experimental myocardial infarction (CTΔex3–6 n = 11; β-catΔex3–6 n = 15 *P < 0.05), while β-catenin-stabilized mice showed a nonsignificant increase of mortality (Fig. 1B). A prominent subendo- and subepicardial layer of cTnTpos cardiomyocytes was found in the scar upon β-catenin depletion, while controls showed a fibrotic scar with only few cTnTpos cells (right panel, Fig. 1A). A similar fibrotic scar was observed in β-catΔex3 mice and their respective controls (right panel, Fig. S5). In summary, depletion of β-catenin in the adult heart attenuates ischemic LV remodeling and postinfarct mortality.

Improved Cardiac Function Upon β-Catenin Depletion Is Not Associated With Changes in Adult Cardiomyocyte Hypertrophy or Apoptosis.

As a molecular and cellular mechanism of attenuated LV remodeling upon β-catenin depletion, we hypothesized adult cardiomyocyte hypertrophy and/or apoptosis to be altered. We investigated hypertrophy and apoptosis 2 and 4 weeks after LAD ligation. We found no significant difference concerning the hypertrophy markers α-skeletal-actin and β-MHC between β-catΔex3–6 mice and their controls 2 weeks after LAD (Fig. S6A). At 4 weeks, neither gene markers of cardiomyocyte hypertrophy nor echocardiographic septal or free wall thickness as a measure of global LV hypertrophy showed any significant differences (Table S1 and Fig. S4). Because hypertrophy of the noninfarcted myocardium contributes to LV remodeling (1), myofiber area was measured in the remote zone. No significant change was detected in β-catΔex3–6 mice (Fig. S6B) or β-catΔex3 mice (data not shown) compared to their control littermates both at 2 and 4 weeks after infarct. In addition, we found no evidence for an altered rate of cardiomyocyte apoptosis as detected by TUNEL assay (Fig. S6C). Therefore, we conclude that the attenuation of cardiac remodeling after ischemia upon β-catenin depletion is not mediated by inhibition of cardiac hypertrophy and/or decreased apoptosis of adult cardiomyocytes.

Resident Cardiac Progenitor Cells Are Targeted by αMHC-Dependent Gene Recombination.

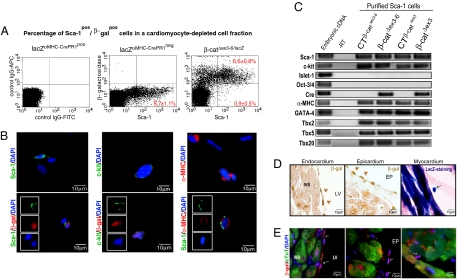

Since neither adult cardiomyocyte apoptosis nor hypertrophy explained the observed phenotype, we asked whether other cardiac cell types, apart from mature cardiomyocytes, were affected by αMHC-dependent gene recombination. The ROSA26 reporter mice allowed for the identification of cells targeted for Cre recombination through detection of β-gal expression. We aimed to identify β-galpos cells using flow cytometry in a cardiomyocyte-depleted cell fraction from adult heart and found ≈10% β-galpos cells. Next, we tested whether the β-galpos cells have stem cell characteristics and analyzed the coexpresssion of the cardiac progenitor cell marker Sca-1. Of the noncardiomyocyte cells, 8.8 ± 0.4% were detected to be Sca-1pos (Fig. S7 A–C). More than 80% of these Sca-1pos cells (6.6 ± 0.8% cells of the total noncardiomyocyte cell population) were β-galpos in both CTΔex3–6/lacZ and β-catΔex3–6/lacZ. lacZαMHC-Cre-neg littermate mice were used as negative controls for β-gal detection (Fig. 2A and data not shown). Similarly, flow cytometry analysis of another heart-specific inducible Cre line, the αMHC-MerCreMer mice (12) mated to the ROSA26 reporter mice showed >60% of the Sca-1pos cells to coexpress β-gal following Cre-induction (Fig. S8A). Immunofluorescence analysis of the noncardiomyocyte cell fraction proved coexpression of the Sca-1 and c-kit epitope in a subpopulation of β-galpos cells. Moreover, αMHC protein expression was observed in a subpopulation of Sca-1pos cells confirming the activation of the endogenous αMHC promoter and protein expression in the identified cell population (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

Activation of the αMHC-promoter in cardiac progenitor cells. (A) Flow cytometry analysis reveals >80% of the noncardiomyocytes to coexpress β-gal and Sca-1 at baseline. Creneg mice were used as negative control. IgG-rabbit-APC and IgG-FITC antibodies were used as a control to discard unspecific staining. (B) Representative immunofluorescence picture of β-galpos cells from the cardiomyocyte depleted cell fraction proving coexpression of the Sca-1 and c-kit epitope. A subpopulation of cells coexpresses αMHC and Sca-1. (C) Analysis of Sca-1 cells gene expression by quantitative real-time PCR documenting expression of αMHC, c-kit, and cardiac transcription markers (GATA4, Tbx5). (D and E) Immunohistochemistry of adult heart from lacZαMHC-Cre mice. Activation of the αMHC promoter was analyzed by β-gal reporter gene expression. Small cells, with a high nuclei/cytoplasm ratio, positive for β-gal were detected by immunoperoxidase, enzymatic lacZ detection, and fluorescence staining in endo-, epi-, and myocardium.

Using magnetic cell sorting (MACS) technology we enriched cardiac Sca-1pos cells from β-catenin depleted, stabilized and their respective control littermates to >95% for further characterization. Independent from the genotypes, mRNA quantification showed coexpression of c-kit. Other known precursor cell markers such as Islet-1 or Oct3/4 were not coexpressed, suggesting different subsets of cardiac precursor cells to be present in the adult heart. Sca-1pos cells from β-catΔex3–6 and β-catΔex3 showed both Cre recombinase and αMHC gene expression consistent with activation of the αMHC promoter in these cells (Fig. 2C). Gene expression of the cardiac transcription factors GATA4, Tbx2, Tbx5, and Tbx20 was detected, confirming that these Sca-1pos/β-galpos cells in the noncardiomyocyte fraction are progenitor cells of the cardiac lineage (Fig. 2C, Fig. S8 D and E).

Aiming to visualize the identified cardiac progenitor cells in vivo, we analyzed heart sections from β-catΔex3–6/lacZ and CTΔex3–6/lacZ mice at baseline. Small intramyocardial β-gal-expressing cells were detected by enzymatic lacZ reaction. In addition, immunoperoxidase detection identified endo- and epicardial β-galpos cells (arrows, Fig. 2D). Heart sections costained with β-gal and cTnT showed a subendo- and subepicardial layer of β-galpos/cTnTneg cells with a large nucleus to cytoplasmic ratio as expected for cardiac precursor cells (Fig. 2E, see Fig. S9 for controls). Double stainings of consecutives slides confirmed β-galpos/Sca-1pos cells to be cTnTneg, GATA4pos, and Tbx5pos (arrows and numbers in Fig. S8 D and E, see S7 for Sca-1 control staining). In conclusion, we identified a population of αMHCpos/Sca-1pos/c-kitpos/GATA4pos/cTnTneg cardiac progenitor cells in an endocardial and epicardial compartment.

Cardiac Progenitor Cell Proliferation and Distribution Following Experimental Infarct.

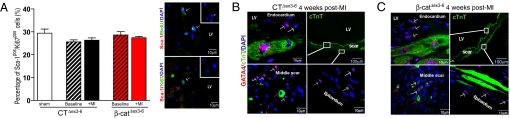

We demonstrated αMHCpos/Sca-1pos/cTnTneg cardiac precursor cells to be targeted for β-catenin depletion. As a hallmark of cardiac precursor cells, a BrdU/Sca-1 and Sca-1pos/Ki67pos double staining identified proliferating Sca-1pos cells. β-Catenin depletion did not affect the number of proliferating Sca-1pos cells (Fig. 3A and Fig. S10B). While these data provide evidence for self-renewal of cardiac resident Sca-1pos precursor cells no evidence was found that differences in proliferation rate explains the observed functional phenotype upon β-catenin depletion.

Fig. 3.

Proliferation and tissue distribution of β-galpos/GATA4pos/cTnTneg cardiac progenitor cells after myocardial infarct. (A) Quantification of Sca-1pos/Ki67pos cell proliferation in a cardiomyocyte-depleted cell fraction by flow cytometry shows no significant differences between CTΔex3–6 and β-catΔex3–6 mice neither at baseline nor after ischemia. Immunofluorescence shows colocalization of Sca-1pos/BrdUpos and Sca-1pos/Ki67pos cells 2 weeks after infarct proving the proliferative capacity of these cells. (B and C) β-Catenin depleted β-catΔex3–6 mice exhibit a layer of cTnTpos cardiomyocytes along the scar, which appears less prominent in control mice (B and C, Upper Right). The subendocardial and subepicardial layer of the infarct scar is populated with small GATA4pos/cTnTneg cells (white arrows). In addition, small GATA4pos/cTnTpos cells are detected within the scar area of both β-catΔex3–6 and control mice (red arrows in B and C, Lower Left). No significant difference in tissue distribution is detected. LV, left ventricle; MI, myocardial infarct.

Next, we asked whether altered migration might contribute to LV remodeling upon β-catenin depletion. We investigated the distribution of Sca-1pos/GATA4pos/cTnTneg cardiac progenitor cells using confocal microscopy in heart sections 2 and 4 weeks after ischemia. At 2 weeks the distribution of β-galpos/Sca-1pos/GATA4pos/cTnTneg progenitor cells and a semiquantification of the Sca-1 cells in the scar vs. remote zone showed no major difference between β-catΔex3–6 and controls (representative pictures in Fig. S10A and data not shown). A prominent layer of GATA4pos/cTnTneg cells was detected along the scar at 4 weeks (white arrows in Fig. 3 B and C). Additionally, a few small GATA4pos/cTnTpos cells were localized in the ischemic region of β-catΔex3–6 and control littermates in the proximity (subendo- and subepicardium) of the compartment where the Sca-1pos/β-galpos cardiac precursor cells were observed initially (endo- and epicardium) (red arrows in Fig. 3 B and C). In summary, we found no evidence that altered migration of cardiac progenitor cells would explain the observed functional phenotype or the more prominent layer of cTnTpos cells in the scar of β-catΔex3–6 mice.

β-Catenin Depletion Enhances Cardiac Progenitor Cell Differentiation After Ischemia.

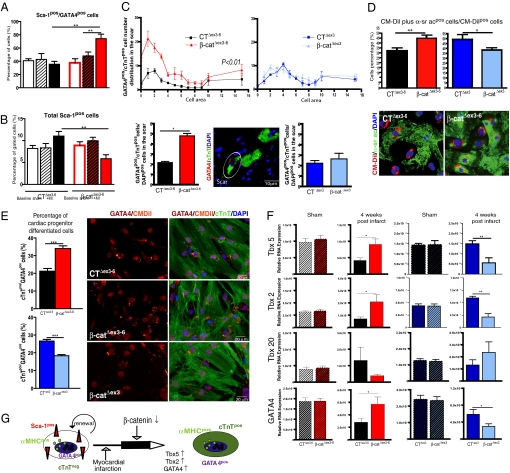

We next asked whether depleting β-catenin alters differentiation of cardiac-resident progenitor cells toward cTnTpos cardiomyocytes. Flow cytometry analysis of the noncardiomyocyte cell fraction revealed the fraction of Sca-1pos cells coexpressing GATA4 to significantly increase in β-catΔex3–6 mice 4 weeks after infarct compared to β-catΔex3–6 mice at baseline and control mice after infarct (Fig. 4A and S8 B and C). This increased expression of cardiac differentiation markers was accompanied by a decrease of total Sca-1pos cells in β-catΔex3–6 mice vs. baseline. Control animals did not decrease the Sca-1pos cell population after infarct (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

β-Catenin depletion enhances cardiomyocyte differentiation of Sca-1pos precursor cells following experimental infarct. (A) Significant increase of the Sca-1pos/GATA4pos cell fraction in β-catΔex3–6 mice 4 weeks after infarct vs. baseline and sham mice, which is not observed in CTΔex3–6 animals. It was accompanied by a nonsignificant decrease of total ScaIpos cells in β-catΔex3–6 mice while control mice tend to upregulate the total Sca-1 cells (B). (C) In Vivo quantification of GATA4pos/cTnTpos cells in the scar with a cell area <16 μm2 shows a significant increase of these cells in β-catΔex3–6 mice compared to controls. A representative confocal image is shown (white circle). (D) In Vitro increased differentiation of isolated Sca-1pos cells toward α-sr acpos cardiomyocytes from β-catΔex3–6 mice compared to isolated Sca-1 cells from CTΔex3–6 mice. The opposite effect was observed in β-catenin-stabilized mice. A representative picture of a 10-day CM-Dil-labeled coculture stained with α-sr ac is shown. (E) Similarly, in vitro differentiation of isolated Sca-1 cells toward GATA4pos/cTnTpos cells increases in β-catΔex3–6 compared to cells from CTΔex3–6 mice. The same cell population is decreased in β-catΔex3 mice. (F) Quantitative real-time PCR of heart samples 4 weeks after infarct shows an increased expression of markers for ventricular cardiomyocyte differentiation Tbx5, Tbx2, and GATA4 in β-catΔex3–6 mice compared to CTΔex3–6. Reciprocal regulation was observed in β-catΔex3 mice in comparison to CTΔex3 mice. (G) Hypothetical scheme of αMHCpos cardiac precursor cells differentiation in vivo triggered by ischemia and amplified by β-catenin depletion. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.001.

If progenitor cell differentiation contributes to stabilize the scar, early cTnTpos-expressing cells with smaller cell size than mature cardiomyocytes should be detectable. Therefore, we analyzed the scar cellularity 4 weeks after ischemia. β-Catenin-depleted mice showed a significant increase of GATA4pos/cTnTpos cells (white circle in Fig. 4C) with <16 μm2 surface area (matched to DAPIpos cell number). In contrast, mice with stabilized β-catenin did not show any significant difference in comparison to their respective controls (Fig. 4C).

To confirm the hypothesis of enhanced precursor cell differentiation upon β-catenin depletion, we performed an in vitro differentiation assay. Isolated Sca-1 cells from β-catenin depleted, stabilized, and respective control littermates were enriched by MACS to >95% purity and labeled with the cell tracer CM-Dil. The cells were cocultured with neonatal mouse (FVB WT strain) cardiomyocytes for 10 days and the number of double α-sarcomeric actin (α-sr ac)pos/CM-Dilpos cells was calculated in relation to the total CM-Dilpos cells. Sca-1pos cells isolated from β-catΔex3–6 mice showed significantly increased differentiation capacity in comparison to cells isolated from controls (CTΔex3–6 n = 10: 38 ± 1.0% of α-sr acpos + CM-Dilpos/total CM-Dilpos; β-catΔex3–6 n = 10: 49.9 ± 2.4% **, P < 0.001, Fig. 4D). Similar to the in vivo situation, we detected an increased percentage of differentiated GATA4pos/cTnTpos cells in β-catenin-depleted cells compared to control cells (CTΔex3–6: 21.2 ± 1.5% vs. β-catΔex3–6: 34.0 ± 1.6% **, P < 0.001, Fig. 4E). In contrast, Sca-1pos cells isolated from β-catenin-stabilized mice exhibited decreased differentiation capacity (CTΔex3 n = 4: 49.1% ± 4.8 of α-sr acpos + CM-Dilpos/total CM-Dilpos; β-catΔex3 n = 6: 38.3 ± 2.1% *, P < 0.05, Fig. 4D) and decreased differentiated GATA4pos/cTnTpos cells (CTΔex3: 26.7 ± 0.9% vs. β-catΔex3: 18.3 ± 0.7% **, P < 0.001, Fig. 4E). Collectively, these data indicate that following chronic LAD ligation, β-catenin depletion enhances resident endogenous Sca-1pos cardiac progenitor cell differentiation toward GATA4pos/cTnTpos/α-sr acpos-expressing cells (scheme in Fig. 4G). Enhancing endogenous repair mechanisms contributes to global LV remodeling including infarct size extension (1).

Reexpression of Cardiac Developmental Transcription Factors in Ischemic Adult Heart.

During embryogenesis, the cardiac mesoderm activates several transcriptional regulators of the cardiac program including GATA4 and members of the T-box family necessary for ventricular cardiac differentiation in response to inductive signals (13). Tbx5 is specifically expressed in the first heart field, which gives rise to left ventricular cardiomyocytes (14). Therefore, we studied Tbx5 and GATA4 expression following infarct via quantitative real-time PCR using heart samples obtained from the apex containing scar tissue, border zone, and remote area. Four weeks after infarct, expression of Tbx2, Tbx5, and GATA4 was significantly upregulated in β-catΔex3–6 mice in comparison to controls and Tbx20 was downregulated. Gene regulation in heart samples from mice with β-catenin stabilization showed the opposite results (Fig. 4F). These data suggest β-catenin depletion in the adult myocardium to induce cardiomyocyte differentiation similar to the embryonic formation of the left ventricle.

Discussion

Our study describes a resident cardiac progenitor cell population exhibiting αMHC-promoter activity and expression of cardiac transcription factors GATA4 and Tbx5 as specific markers for the first heart field (FHF) giving rise to the left ventricle during embryonic cardiac development. Enhancing signaling cascades orchestrating LV embryonic cardiomyocyte differentiation, namely depletion of β-catenin, positively affects global LV function and survival at 4 weeks. We suggest enhanced cardiomyocyte differentiation of endogenous cardiac resident stem cells to mediate this effect by limiting secondary infarct expansion.

β-Catenin Depletion Attenuates Postischemic Mortality.

Infarct mortality was ameliorated by β-catenin depletion already during the first 2 weeks post infarct. Similarly, ubiquitous overexpression of the Wnt signaling antagonist frizzledA, which prevents β-catenin accumulation after infarct, resulted in reduced mortality between 2 and 5 days after permanent LAD ligation because of reduced cardiac rupture (15). Fatal arrhythmias resulting from “vulnerable” myocardium might be reduced through the effects of β-catenin on cellular scar composition. In association with the improved LV function following infarct, we found an increased number of cTnTpos-expressing cells with small cell size upon β-catenin depletion. These data suggest that despite the dramatic size difference between the small-identified cTnTpos cells in the scar and the adult cardiomyocytes, these cells might positively affect secondary scar expansion (16) and therefore affect ventricular wall stability early on.

Cardiomyocyte Hypertrophy and Apoptosis Upon β-Catenin Depletion.

Four weeks after chronic LAD ligation mice with β-catenin depletion exhibited a complete lining of cTnTpos cells along the scar subendocardium and subepicardium, while control animals showed only scattered cTnTpos cells. One explanation is that these cells might have survived the initial hypoxia through increased expression of survival genes. However, we have not observed significant differences in the TUNEL analysis. A second explanation is that β-catenin influences proliferation but β-catenin depletion did not alter proliferation as quantified by analysis of Sca-1pos/Ki67pos cells. Accordingly, β-catenin depletion in the early mesoderm decreased proliferation of cardiac precursor cells in the embryonic FHF (17). Upregulation of β-catenin enhances expansion of Islet-1 cardiac stem cells (7, 18). Lastly, hypertrophy of surviving cardiomyocytes was demonstrated to be unaffected upon β-catenin depletion. Thus, none of the cellular mechanisms involving αMHC-dependent gene recombination in adult cardiomyocytes sufficiently explains the phenotype observed here.

Identification of αMHCpos Cardiac Resident Precursor Cells.

Employing the ROSA26 reporter mice in which the expression of the lacZ gene depends on Cre activation, we documented αMHC-dependent gene recombination, mRNA, and protein expression in a cTnTneg cell population. Cardiac stem cells were previously shown to express αMHC during early cardiac developmental stages in embryoid bodies in vitro (8). As the adult cardiac cell population under investigation here expresses markers of cell proliferation (Ki67, BrdU) and cardiomyocyte lineage markers (GATA4, Tbx5) it fulfills the criteria of a cardiac endogenous precursor cell. It overlaps in part with the Sca-1 and c-kit positive cardiac stem cell population; however, the cells are negative for Islet-1 and Oct3/4.

Two distinct mesodermal populations participate in the formation of the heart. The earliest progenitor cell population corresponds to the FHF, which expresses Tbx5 during differentiation and gives rise to the LV (14). The second population identified by Islet-1 expression corresponds to the second heart field (SHF) from which right ventricle, atria, and outflow tract will arise (17, 19–21). Our findings of the coexpression of αMHC and specific cardiac transcription factors like GATA4, and Tbx5 characteristic for the LV, suggest the existence of an αMHCpos/cTnTneg cardiac committed FHF stem cell population in the adult heart. This population was identified in the endo- and epicardial compartment resembling the localization of tissue-resident cardiac precursors already described in zebrafish (22). Similarly, subepicardial and subendocardial cardiac precursor cells have been identified in mammalian cardiac development (23, 24).

β-Catenin Downregulation Improves Cardiac Function After Experimental Infarct.

Previous studies suggest a negative role for Wnt/β-catenin during cardiac differentiation (7, 25, 26). Active β-catenin signaling supports stemness and delays differentiation of cardiac precursors in vivo and in vitro (27). Gene expression analysis from differentiating αMHCpos embryonic stem-derived cells in comparison to nondifferentiating cells showed upregulation of negative regulators of the Wnt signaling (8). We identified a subpopulation of cardiac resident progenitors committed to the cardiac lineage to be targeted for β-catenin depletion, which results in enhanced differentiation. Similar observations have been described for Islet-1pos cardiac precursors: differentiation decreased upon β-catenin stabilization while proliferation of the undifferentiated cells is enhanced (7). Moreover, upregulation of Tbx5 and GATA4 gene expression was observed after ischemia, suggesting a reactivation of the LV cell differentiation program in adult heart in adaptation to injury.

We suggest that endogenous cardiac regeneration contributes to LV remodeling following chronic ischemia through differentiation of resident precursor cells, amplified by β-catenin downregulation. Similarly, increased differentiation of Sca-1pos resident cardiac precursor cells was observed upon upregulation of FGF2. Depletion of FGF2 was found to worsen LV remodeling by enhancing secondary infarct expansion (7, 25, 26). We propose limited secondary infarct expansion to contribute to the improved cardiac function after infarct in our study.

We cannot exclude the participation of other precursor cell populations or cellular mechanisms. However, the data suggest endogenous cardiac regeneration to significantly contribute to adult cardiac remodeling upon stress in addition to other mechanisms previously recognized as adult cardiomyocyte apoptosis or hypertrophy.

Materials and Methods

Mouse Strains.

The different mouse lines, β-catΔex3–6, β-catΔex3, and the ROSA26 reporter mice (Jackson Laboratory) were described before (9, 28). Mice were bred in a mixed C57BL/6 + FVB background (β-cat Δex3–6) or FVB background (β-catΔex3). All of the procedures involving animals were approved by the Berlin animal review board (Reg. 0135/01 and Reg. 0338/05).

Flow Cytometry.

Mice hearts were dissected and a myocyte-depleted population was prepared by mincing, homogenizing, and filtering the myocardium subsequently through 40-μm (BDFalcon) and 30-μm mesh (Miltenyi Biotec). Isolated cells were labeled with Sca-1-FITC (eBioscience); GATA4 (Santa Cruz); Ki67 (Abcam) and β-gal (MP Biomedicals) antibodies. The αMHC-specific antibody was kindly provided by J. Robbins, Cincinnati. Isotype controls were used in each experiment. Each mouse had 104 cells subjected to flow cytometry. Cell fluorescence signals were detected with a FACScalibur flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson).

Differentiation Assay.

Sca-1pos cells were enzymatically dissociated as described previously (4) from adult murine heart. Cell suspension was filtered and incubated with FITC-conjugated anti-Sca-1 antibody (20 min at −4 °C). Next, cells were incubated with anti-FITC microbeads (30 min at −4 °C). Sca-1pos cells were purified by two cycles of MACS column (Miltenyi). The purity was confirmed by flow cytometry (>95%). The cells were labeled with the CM-Dil cell tracer (Molecular Probes) and cocultured with neonatal cardiomyocytes in fibronectin-coated chamber slides at a ratio of ¼ in DMEM/10%FBS/antibiotics (37 °C, 5% CO2). After 10 days, cocultures were fixed with 4% PFA and stained. Cells were quantified under fluorescence microscope.

Statistical Analysis.

Statistical analyses were performed using unpaired, two-tailed Student's t or ANOVA tests followed by posthoc analysis employing the Bonferroni tests. Data are reported as mean ±SEM. P < 0.05 values were considered significant.

For more detail and primers see SI Materials and Methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

The authors thank Bärbel Pohl and Martin Taube [Max Delbrück Center (MDC)] for technical assistance. This study was funded in part by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft grant BE 8–1 and 8–2 and Juergen Manchot Foundation (to M.W.B.); by the Ernst und Berta Grimmke Foundation (to L.C.Z.); by the Foundation J. Leducq and the FP6-I.P “EuGeneHeart” (UE LSHM-CT 05–018833) (to J.L.B.). We thank M.D. Schneider (Imperial College, London) for providing the αMHC-CrePR1 mice, W. Birchmeier (MDC, Berlin) for providing the β-catflox/floxex3–6, M. Taketo (Kyoto, Japan) for providing β-catflox/floxex3, and J. Molkentin (Cincinnati) for providing αMHC-MerCreMer mice. We especially thank J. Robbins (Cincinnati) for providing the specific αMHC antibody.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0808393105/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Virag JA, et al. Fibroblast growth factor-2 regulates myocardial infarct repair. Effects on cell proliferation, scar contraction, and ventricular function. Am J Pathol. 2007;171:1431–1440. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.070003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hsieh PCH, et al. Evidence from a genetic fate-mapping study that stem cells refresh adult mammalian cardiomyocytes after injury. Nat Med. 2007;13:970–974. doi: 10.1038/nm1618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oka T, Xu J, Molkentin JD. Re-employment of developmental transcription factors in adult heart disease. Sem Cell Dev Biol. 2007;18:117–131. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2006.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oh H, et al. Cardiac progenitor cells from adult myocardium: Homing, differentiation, and fusion after infarction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:5834–5839. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2132126100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Foley AC, Mercola M. Heart induction by Wnt antagonists depends on the homeodomain transcription factor Hex. Genes Dev. 2005;19:387–396. doi: 10.1101/gad.1279405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lickert H, et al. Formation of multiple hearts in mice following deletion of beta-catenin in the embryonic endoderm. Dev Cell. 2002;3:171–181. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00206-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Qyang Y, et al. The renewal and differentiation of Isl1+ cardiovascular progenitors are controlled by a Wnt/beta-catenin pathway. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1:165–179. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Doss MX, et al. Global transcriptome analysis of murine embryonic stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes. Genome Biol. 2007;8:992. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-4-r56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baurand A, et al. Beta-Catenin downregulation is required for adaptive cardiac remodeling. Circ Res. 2007;100:1353–1362. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000266605.63681.5a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zambrowicz BP, et al. Disruption of overlapping transcripts in the ROSA beta geo 26 gene trap strain leads to widespread expression of beta-galactosidase in mouse embryos and hematopoietic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:3789–3794. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.8.3789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harada N, et al. Intestinal polyposis in mice with a dominant stable mutation of the beta-catenin gene. EMBO J. 1999;18:5931–5942. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.21.5931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sohal DS, et al. Temporally regulated and tissue-specific gene manipulations in the adult and embryonic heart using a tamoxifen-inducible Cre protein. Circ Res. 2001;89:20–25. doi: 10.1161/hh1301.092687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mori AD, et al. Tbx5-dependent rheostatic control of cardiac gene expression and morphogenesis. Dev Biol. 2006;297:566–586. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bruneau BG, et al. Chamber-specific cardiac expression of Tbx5 and heart defects in Holt-Oram syndrome. Dev Biol. 1999;211:100–108. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barandon L, et al. Reduction of infarct size and prevention of cardiac rupture in transgenic mice overexpressing FrzA. Circulation. 2003;108:2282–2289. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000093186.22847.4C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beltrami AP, et al. Adult cardiac stem cells are multipotent and support myocardial regeneration. Cell. 2003;114:763–776. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00687-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klaus A, Saga Y, Taketo MM, Tzahor E, Birchmeier W. Distinct roles of Wnt/beta-catenin and Bmp signaling during early cardiogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:18531–18536. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703113104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cohen ED, et al. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling promotes expansion of Isl-1-positive cardiac progenitor cells through regulation of FGF signaling. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:1794–1804. doi: 10.1172/JCI31731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lin L, et al. beta-Catenin directly regulates Islet1 expression in cardiovascular progenitors and is required for multiple aspects of cardiogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:9313–9318. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700923104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kwon C, et al. Canonical Wnt signaling is a positive regulator of mammalian cardiac progenitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:10894–10899. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704044104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Urbanek K, et al. Myocardial regeneration by activation of multipotent cardiac stem cells in ischemic heart failure. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:8692–8697. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500169102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lepilina A, et al. A dynamic epicardial injury response supports progenitor cell activity during zebrafish heart regeneration. Cell. 2006;127:607–619. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.08.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liebner S, et al. β-Catenin is required for endothelial-mesenchymal transformation during heart cushion development in the mouse. J Cell Biol. 2004;166:359–367. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200403050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kruithof BP, et al. BMP and FGF regulate the differentiation of multipotential pericardial mesoderm into the myocardial or epicardial lineage. Dev Biol. 2006;295:507–522. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Naito AT, et al. Developmental stage-specific biphasic roles of Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in cardiomyogenesis and hematopoiesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:19812–19817. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605768103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ueno S, et al. Biphasic role for Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in cardiac specification in zebrafish and embryonic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:9685–9690. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702859104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Anton R, Kestler HA, Kuhl M. β-Catenin signaling contributes to stemness and regulates early differentiation in murine embryonic stem cells. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:5247–5254. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Soriano P. Generalized lacZ expression with the ROSA26 Cre reporter strain. Nat Genet. 1999;21:70–71. doi: 10.1038/5007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.