Abstract

Context

In vitro studies and anecdotal clinical reports have suggested that clinically significant rebound hypercoagulability may occur after discontinuation of oral anticoagulants (OACs), such as vitamin K antagonists and ximelagatran, for venous thromboembolism (VTE).

Objective

Assess the extent to which rebound hypercoagulability-related VTE recurrences occur in the 2 months following discontinuation of OACs.

Data sources

Published, randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of OAC treatment of VTE.

Study selection

RCTs of varying durations of OAC treatment of VTE that include VTE recurrence (or extension) data for more than 2 months after discontinuation of anticoagulants.

Data extraction

Rates of VTE recurrences (1) while taking OACs, (2) within 2 months of discontinuing OACs, and (3) from > 2 months until the end of the study were extracted along with major bleeding episodes while on OACs. The rate of VTE recurrences possibly attributable to rebound hypercoagulability was estimated by subtracting the VTE recurrence rate after the 2-month rebound period from the rate during the rebound period.

Data synthesis

In 20 trials (n = 5822), VTE recurrences were 2.62 times as frequent in the 2 months following discontinuation of OACs as subsequently (1.57% VTE recurrences per month falling to 0.56% per month, odds ratio = 2.62, 95% confidence interval: 2.19-3.14), corresponding to 2.02% of patients with rebound hypercoagulability-related VTE recurrences (1.57% per month - 0.56% per month × 2 months = 2.02%). In the 11 trials with evaluable data from the shorter- and longer-duration OAC arms, total adverse events (VTE recurrences plus major bleeding) over the entire durations of the trials were not significantly different.

Conclusions

Rebound hypercoagulability accounts for about 2% of patients having recurrent VTE in the first 2 months after discontinuing OACs. RCTs evaluating the efficacy of OACs should include data for at least 2 months following OAC treatment. Increasing the duration of OAC treatment does not reduce the overall adverse events.

Introduction

Rebound hypercoagulability (elevated levels of fibrinogen, fibrinopeptide A, thrombin, thrombin-antithrombin III complexes, coagulation factors VII and IX levels, and activated thromboplastin) occurs in vitro in the first few weeks after discontinuation of vitamin K antagonists (VKAs), and by 2 months these tests are no longer abnormal.[1–4] Relative to abruptly withdrawing warfarin, rebound thrombin generation is not reduced by an additional month of a low, fixed dose of warfarin.[3] Tapering VKAs has been reported to ameliorate rebound hypercoagulability[1] and as nonbeneficial.[4]

Several studies have reported increased rates of thrombotic complications within 2 months of discontinuing warfarin.[2,5–7]

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of anticoagulation with oral anticoagulants (OACs), such as VKAs and ximelagatran, for venous thromboembolism (VTE) generally have compared venous and arterial thrombosis rates for patients only while on study. If rebound hypercoagulability due to OACs causes thrombosis in the weeks following discontinuation of anticoagulation, then this should be considered in the interpretation of studies of anticoagulation.

This article analyzes RCTs of VTE treatment with OACs in which VTE recurrence rates per month within 2 months of discontinuation of OACs can be compared with subsequent VTE recurrence rates. Several questions are addressed:

What is the rate of VTE recurrence (1) while patients are taking OACs, (2) in the 2-month period following discontinuation of OACs, and (3) from > 2 months until the end of the trial?

How do short- and long-duration OAC arms of the RCTs compare with VTE recurrences over the entire duration of the trials?

How do short- and long-duration OAC arms of the RCTs compare with total adverse events (VTE recurrences plus major bleeding) over the entire duration of the trials?

What is the estimated rate of VTE recurrences possibly attributable to rebound hypercoagulability?

Are rates of VTE recurrences possibly related to hypercoagulability (the first 2 months after stopping treatment) similar to when OAC treatment is given for ≤ 3 months compared with ≥ 6 months?

Methods

Data Sources

A MEDLINE search (July 2008) for appropriate RCTs had the following string of search terms: “(vitamin K antagonist or vitamin K inhibitor or warfarin or acenocoumarol or dicumarol or fluindione or ximelagatran) AND (venous thromboembolism or pulmonary embolism or pulmonary emboli or deep venous thrombosis) AND (randomized controlled trial).” There were no date restrictions. Only reports in the English language could be considered. Studies were also included from a Cochrane meta-analysis of RCTs of trials comparing different durations of OAC treatments,[8] and the reference list from this meta-analysis and from published RCTs of VTE treatment.

Study Selection

Trials were excluded if:

No event data were reported for more than 2 months after discontinuation of OACs;

The timing of VTE recurrences was not reported;

A surrogate rather than a clinical endpoint was used (eg, positive Doppler leg scan in an asymptomatic patient) rather than a clinical recurrence (or extension);

The report duplicated an included study;

The study was not an RCT;

The RCT did not involve treatment of VTE;

OAC treatment was not a focus of the study; or

The report was in a language other than English.

Failure to have objective tests confirming the diagnoses of VTE for all subjects was not considered an exclusion. However, such trials were separately analyzed to see whether they affected the overall results.

Data Extraction

Data on VTE recurrences (1) while on OACs, (2) in the 2 months after discontinuing OACs, and (3) subsequently were extracted from published RCTs of OAC treatment of VTE. The rate of major hemorrhage per month of OAC treatment, if available, was also assessed.

To estimate the number of subject-months at risk for each phase of a trial, the numbers of subjects who (1) began the trial, (2) finished the anticoagulation period, (3) finished 2 months after anticoagulation cessation, and (4) completed the follow-up time were extracted from the publication. For each trial phase (ie, anticoagulation, 2-month rebound period, and post rebound until the end), the numbers of subjects participating in the trial at the beginning and end of the period were summed and the result divided by 2. That result was multiplied by the number of months in the period. For instance, if 100 subjects entered the trial and 80 completed the 6-month period of anticoagulation, the months at risk for adverse events (VTE recurrences and major bleeding) would be 540 months ([100 + 80]/2 = 90; 90 × 6 months = 540 months).

The VTE recurrences possibly attributable to rebound hypercoagulability due to OAC withdrawal were estimated by subtracting the rate of VTE recurrences after the 2-month rebound period from the rate during the 2-month rebound period.

Outcome Measures

With the extracted data, comparisons were made of the following:

VTE recurrences in the 2 months after discontinuing OACs vs subsequently, also broken down by durations of OAC treatment (≤ 3 months and ≥ 6 months);

In the RCTs with evaluable data from subjects receiving shorter vs longer durations of OACs, overall VTE recurrence rates in shorter vs longer duration OAC treatment arms of RCTs; and

In the RCTs with evaluable data from subjects receiving shorter vs longer durations of OACs, overall rate of adverse events (VTE recurrences plus major hemorrhages) in shorter vs longer duration OAC treatment arms of RCTs.

Statistical Analysis

Rates were calculated as (1) VTE recurrences and major bleeds while taking OACs per subject and (2) VTE recurrences and major bleeds per month of OAC treatment. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated with a chi-square function to make the comparisons. For the VTE recurrences in the 2 months post OACs vs the monthly rate from > 2 months until the end of the trial, a subgroup analysis of studies of similar OAC duration (ie, ≤ 3 months vs ≥ 6 months) was used as a stratification variable in the primary analysis of the combined studies to determine whether duration of OAC treatment affected outcomes. A fixed-effects approach was used, and statistical heterogeneity across all the trials was tested with the I2 statistic. Funnel plots were used to test for possible publication bias.

RevMan 5.1.14 from the Cochrane Collaboration was used to perform chi-square comparisons of the RCT study arms, forest plots, funnel plots, and heterogeneity assessments.

Results

Out of 228 matches from the MEDLINE search, 209 studies were excluded for the following reasons:

No event data were reported for more than 2 months after discontinuation of OACs: 40;

Timing of VTE recurrences was not reported: 17;

A surrogate rather than a clinical endpoint was used (eg, positive Doppler leg scan in an asymptomatic patient) rather than a clinical recurrence (or extension): 4;

The report duplicated an included study: 7;

The study was not an RCT: 17;

The RCT did not involve treatment of VTE: 100;

OAC treatment was not a focus of the study: 33; and

The report was in a language other than English: 1.

Table 1 shows the 37 arms of 20 studies that met the criteria of having data on VTE recurrences for more than 2 months subsequent to discontinuation of OACs and the timing of VTE recurrences.[9–28]

Table 1.

Study Characteristics

| Number | Study | Eligibility | N | OAC Warfarin = 1 Fluindione = 2 Acenocoumarol = 3 Dicumarol = 4 Ximelaga-tran = 5 | Trial Schedule: Months of OAC Treatment and Follow-up | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pretrial | On-Trial Planned (Actual) | Follow-up of OAC Planned (Actual) | |||||

| 1 | Agnelli (2001)[9] | DVT | 133 | 1 or 3 | 3 | 0 (0.0) | 24-66 (37.2) |

| 2 | Agnelli (2001)[9] | DVT | 134 | 1 or 3 | 3 | 9 (8.8) | 15-57 (28.2) |

| 3 | Agnelli (2003)[10] | DVT | 161 | 1 or 3 | 3 | 0 (0.0) | 36 (32.1) |

| 4 | Agnelli (2001)[9] | DVT | 164 | 1 or 3 | 3 | 3-9 (6.3) | 30 (26.4) |

| 5 | Campbell (2007)[11] | VTE | 369 | 1 | 0 | 3 (3.0) | 9 (8.2) |

| 6 | Campbell (2007)[11] | VTE | 380 | 1 | 0 | 6 (5.4) | 6 (5.9) |

| 7 | Daskalopoulos (2005)[12] | DVT | 52 | 3 | 0 | 6 (5.4) | 6 (5.9) |

| 8 | Fennerty (1987) [13] | VTE | 49 | 1 | 0 | 0.7 (0.7) | 11.3 (10.7) |

| 9 | Fennerty (1987)[13] | VTE | 51 | 1 | 0 | 1.4 (1.4) | 10.6 (9.8) |

| 10 | Harenberg (2006)[14] | VTE | 32 | 5 | 6 | 6 (6.0) | 18 (16.6) |

| 11 | Harenberg (2006)[14] | VTE | 32 | 1 | 6 | 6 (6.0) | 18 (16.9) |

| 12 | Harenberg (2006)[14] | VTE | 9 | 5 | 18 | 18 (18.0) | 18 (15.0) |

| 13 | Harenberg (2006)[14] | VTE | 14 | 5 or 1 | 18 | 0 (0.0) | 36 (29.6) |

| 14 | Holmgren (1985)[15] | First DVT | 69 | OAC not otherwise specified | 0 | 1 (0.9) | 11 (10.0) |

| 15 | Holmgren (1985)[15] | First DVT | 66 | OAC nos | 0 | 6 (5.6) | 6 (5.4) |

| 16 | Hull (2006)[16] | DVT in cancer patients | 100 | 1 | 0 | 3 (2.5) | 9 (4.9) |

| 17 | Kearon (1999)[17] | First VTE | 83 | 1 | 3 | 0 (0.00) | 1-24 (9.0) |

| 18 | Kearon (2004)[18] | First VTE | 58 | 1 | 1 | 0 (0.00) | 11 (10.5) |

| 19 | Lagerstedt (1985)[19] | Calf VT | 23 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 9 (9.0) |

| 20 | Levine (1995)[20] | DVT | 104 | 1 | 1 | 0 (0.0) | 11 (9.9) |

| 21 | Levine (1995)[20] | DVT | 109 | 1 | 1 | 2 (2.0) | 9 (7.6) |

| 22 | Levine (1995)[20] | DVT | 192 | 1 | 1 | 2 (1.8) | 9 (8.1) |

| 23 | Palareti (2006)[21] | VTE | 624 | 1 or 3 | 3-12 | 0 (0.0) | 8-18 (15.6) |

| 24 | Pinede (2001)[22] | VTE | 270 | 2 | 0 | 3 (2.8) | 12.3 (11.7) |

| 25 | Pinede (2001)[22] | VTE | 269 | 2 | 0 | 6 (5.5) | 9.5 (8.6) |

| 26 | Ridker (2003)[23] | VTE | 253 | 1 | 6.4 | 0 (0.00) | 1-52 (25.2) |

| 27 | Schulman (1985)[24] | First DVT | 10 | 1 | 0 | 1.5 (1.5) | 18-30 (23) |

| 28 | Schulman (1985)[24] | First DVT | 10 | 1 | 0 | 3 (3.0) | 16-25 (20) |

| 29 | Schulman (1985)[24] | First DVT | 17 | 1 | 0 | 3 (2.9) | 15-28 (22) |

| 30 | Schulman (1985)[24] | First DVT | 18 | 1 | 0 | 6 (5.8) | 18-28 (20.5) |

| 31 | Schulman (1985)[24] | Second DVT | 9 | 1 | 0 | 6 (6.0) | 26-39 (32) |

| 32 | Schulman (1985)[24] | First DVT | 9 | 1 | 0 | 1.5 (1.5) | 18-30 (23) |

| 33 | Schulman (1995)[25] | Second DVT | 443 | 1 or 4 | 0 | 1.4 (1.2) | 22.5 (19.8) |

| 34 | Schulman (1995)[25] | First DVT | 454 | 1 or 4 | 0 | 6 (5.1) | 18 (15.4) |

| 35 | Schulman (1997)[26] | Second DVT | 111 | 1 or 4 | 0 | 6 (7.7) | 42 (31.4 |

| 36 | Schulman (2003)[27] | VTE | 611 | 5 | 6 | 0 (0.0) | 18 (16.9) |

| 37 | van Gogh (2007)[28] | VTE | 353 | 1 or 3 | 6 | 0 (0.0) | 12 (8.6) |

| Total | 5822 | ||||||

DVT = deep venous thrombosis; OAC = oral anticoagulant; VTE = venous thromboembolism

Main Outcomes

While on OACs, 0.49% of subjects per month had VTE recurrences and 0.38% per month had major hemorrhages (Table 2).

Table 2.

VTE Recurrences and Major Bleeds While Taking OACs

| Number | Trial Lead Author (Year), Intended Duration of On-trial OACs in Months | n/Months on OACs | VTE Recurrences/VTE Recurrences/n (%)/VTE Recurrences per Month (%) | Major Bleeds/Major Bleeds/n (%)/Major Bleeds per Month (%) |

| 1 | Agnelli (2001),[9] 0 | No VKA given after trial began | ||

| 2 | Agnelli (2001),[9] 10 | 134/1179 | 3/2.24/0.25 | 2/2.24/0.25 |

| 3 | Agnelli (2003),[10] 0 | No VKA given after trial began | ||

| 4 | Agnelli (2001),[10] 3-9 | 164/1040 | 2/1.22/0.19 | 4/2.44/0.38 |

| 5 | Campbell (2007),[11] 3 | 369/1107 | 7/1.90/0.63 | 0/0.00/0.00 |

| 6 | Campbell (2007),[11] 6 | 380/2052 | 13/3.42/0.63 | 8/2.11/0.39 |

| 7 | Daskalopoulos (2005),[12] 6 | 52/273 | 3/5.77/1.10 | 4/7.69/1.47 |

| 8 | Fennerty (1987)[13] 0.75 | 49/37 | 0/0.00/0.00 | Not reported |

| 9 | Fennerty (1987),[13] 1.4 | 51/71 | 0/0.00/0.00 | Not reported |

| 10 | Harenberg (2006),[14] 0 | No VKAs given after trial began | ||

| 11 | Harenberg (2006),[14] 6 | 32/192 | 0/0.00/0.00 | 1/3.13/0.52 |

| 12 | Harenberg (2006),[14] 6 | 32/192 | 0/0.00/0.00 | 0/0.00/0.00 |

| 13 | Harenberg (2006),[14] 18 | 9/162 | 0/0.00/0.00 | 0/0.00/0.00 |

| 14 | Holmgren (1985),[15] 1 | 58/50 | 3/5.17/6.00 | 1/1.72/2.00 |

| 15 | Holmgren (1985),[15] 6 | 53/297 | 3/5.66/1.01 | 0/0.00/0.00 |

| 16 | Hull (2006),[16] 3 | 100/250 | 10/10.0/4.00 | 7/7.00/2.80 |

| 17 | Kearon (1999),[17] 0 | No VKAs given after trial began | ||

| 18 | Kearon (2004),[18] 0 | No VKAs given after trial began | ||

| 19 | Lagerstedt (1985),[19] 3 | 23/69 | 0/0.00/0.00 | 0/0.00/0.00 |

| 20 | Levine (1995),[20] 0 | No VKA given after trial began | ||

| 21 | Levine (1995),[20] 2 | 109/189 | 1/0.92/0.53 | 1/0.95/0.53 |

| 22 | Levine (1995),[20] 2 | 192/384 | 0/0.00/0.00 | Not reported |

| 23 | Palareti (2006),[21] 0 | No VKA given after trial began | ||

| 24 | Pinede (2001),[22] 3 | 270/756 | 2/0.74/0.26 | 5/1.85/0.66 |

| 25 | Pinede (2001),[22] 6 | 269/1480 | 5/1.86/0.34 | 7/2.60/0.47 |

| 26 | Ridker (2003),[23] 0 | No VKAs given after trial began | ||

| 27 | Schulman (1985),[24] 1.5 | 10/15 | 0/0.00/0.00 | 0/0.00/0.00 |

| 28 | Schulman (1985),[24] 3 | 10/30 | 0/0.00/0.00 | 0/0.00/0.00 |

| 29 | Schulman (1985),[24] 3 | 16/46 | 1/6.25/2.17 | 1/6.25/2.17 |

| 30 | Schulman (1985),[24] 6 | 16/93 | 0/0.00/0.00 | 1/6.25/1.08 |

| 31 | Schulman (1985),[24] 6 | 9/54 | 0/0.00/0.00 | 1/11.1/1.85 |

| 32 | Schulman (1985),[24] 1.5 | 8/90 | 0/0.00/0.00 | 1/12.5/1.11 |

| 33 | Schulman (1995),[25] 1.4 | 441/529 | 6/1.36/1.13 | 1/0.23/0.19 |

| 34 | Schulman (1995),[25] 6 | 451/2300 | 7/1.55/0.30 | 5/1.11/0.22 |

| 35 | Schulman (1997),[26] 6 | 111/855 | 1/0.90/0.12 | 3/2.70/0.35 |

| 36 | Schulman (2003),[27] 0 | Off ximelagatran at start | ||

| 37 | van Gogh (2007),[28] 0 | No VKAs given after trial began | ||

| Total | 3418/13,792 | 67/1.96/0.49 | 53/1.55/0.38 | |

OACs = oral anticoagulants; VKA = vitamin K antagonists; VTE = venous thromboembolism

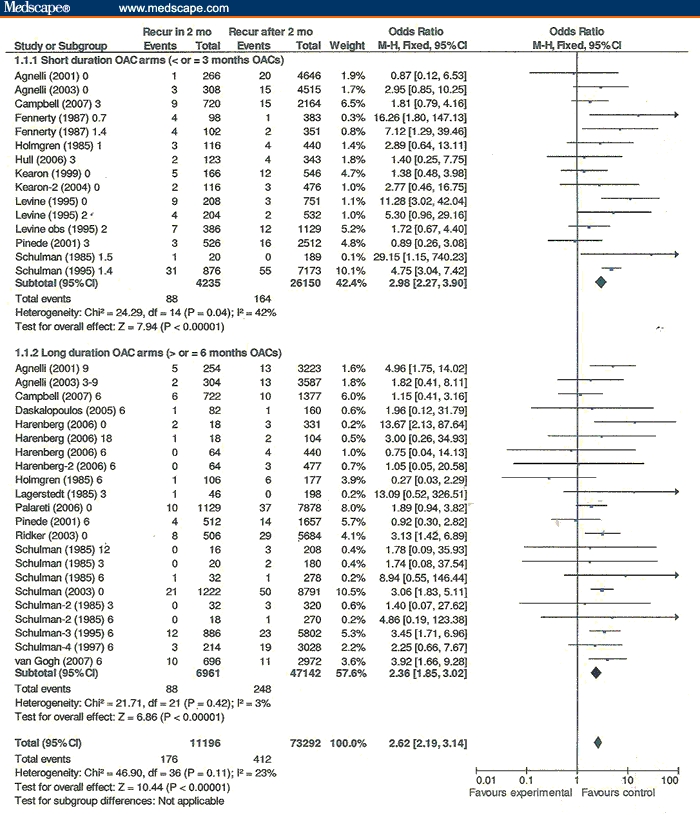

VTE recurrences in these trials were 2.62 times as frequent in the 2 months following discontinuation of OACs compared with subsequently (Figure 1). The OAC treatment duration arms of ≤ 3 months had a greater tendency for rebound VTE recurrences than treatment arms of ≥ 6 months (OR = 2.98, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 2.27-3.90 vs OR = 2.36, 95% CI = 1.85-3.02). Heterogeneity in ≤ 3 months OAC treatment duration arms exceeded that in ≥ 6 months (42% vs 3%). Without the outlier Schulman 1995 RCT with 6 weeks of VKAs after the second deep venous thromboembolism episode,[25] the rate of VTE recurrences in the 2 months following discontinuation vs from > 2 months until the end of the trial in the ≤ 3 months OAC treatment arms was similar to that in the ≥ 6 months OAC treatment arms (OR = 2.42, 95% CI = 1.73-3.39 vs OR = 2.36, 95% CI = 1.85-3.02).

Figure 1.

Venous thromboembolism recurrences within 2 months of stopping oral anticoagulants/# months vs recurrences after 2 months/# months.

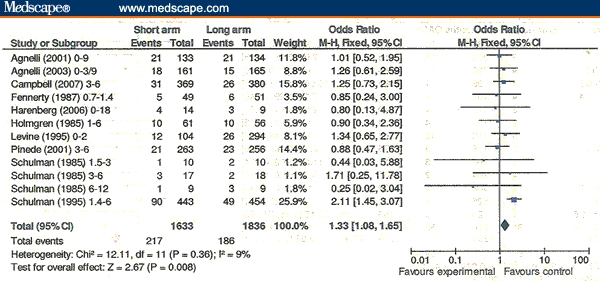

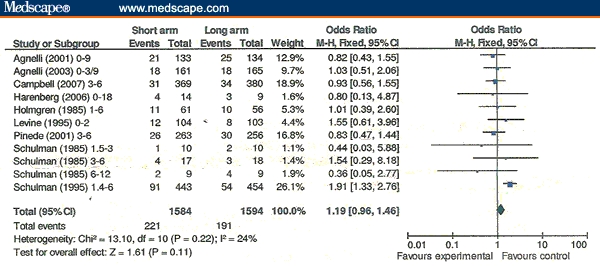

In the 12 RCTs with both shorter- and longer-duration OAC treatment arms evaluable, overall rates of VTE recurrences were significantly less with longer-duration OACs vs shorter-duration OACs (Figure 2). The Schulman 1995[25] outlier RCT accounts for this difference (OR = 2.11, 95% CI = 1.45-3.07 vs OR = 1.06, 95% CI = 0.82-1.38 for the other 11 RCTs). When major bleeding events are added to VTE recurrences (ie, total adverse events), there is no longer a significant difference favoring longer anticoagulation (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Overall venous thromboembolism (VTE) recurrences. VTE recurrences/n: short-duration oral anticoagulant (OAC) arm vs long-duration OAC arm.

Figure 3.

Adverse events overall. Venous thromboembolism recurrences plus major bleeds in short- vs long-duration oral anticoagulant arms.

Omitting trials in which all subjects did not have objective tests confirming the diagnoses of VTE[13,15,19,24] did not significantly change any of the findings.

The increased VTE recurrence rate following discontinuation of ximelagatran was almost identical to the increased incidence of recurrences after stopping VKAs (In Figure 1 Schulman 2003,[27] OR = 3.06 [95% CI = 1.83-5.11] vs OR = 2.62 [95% CI = 2.19-3.14] overall).

About 2% of subjects had a VTE recurrence possibly attributable to rebound hypercoagulability in the 2 months after stopping OACs on the basis of subtracting the rate after 2 months from the rate in the first 2 months after OAC cessation (Figure 1: 1.57% [176/11,196] - 0.56% [412/73,292] = 1.01% per month; for 2 months = 2.02%). The rate of VTE recurrences possibly attributable to rebound hypercoagulability for subjects receiving ≤ 3 months (2.70%: rate in the first 2 months: 2.08% [88/4235] - rate from > 2 months until the end of the trial: 0.63% [164/26,150] = 1.35%, for 2 months = 2.70%) was less than for those receiving ≥ 6 months of OACs (1.46%: rate in the first 2 months: 1.26% [88/6961] - rate from > 2 months until the end of the trial: 0.53% [248/47,142] = 0.73%; for 2 months = 1.46%).

Funnel plots did not show asymmetry, suggestive of publication bias.

Comment

The spike in VTE recurrences post OAC might alternately be explained without invoking causation by rebound hypercoagulability. The natural history of VTE subjects is thought to have a declining risk for VTE recurrence post deep venous thromboembolism or pulmonary embolism.[29] We don't know the extent to which this natural history is changed by the anticoagulation, because anticoagulation became standard treatment of VTE on the basis of observational studies in the 1940s and 1950s before placebo-controlled RCTs documented the extent of VTE recurrence reduction while on OACs. The naturally declining risk over time may occur partly due to the depletion of susceptible high-risk patients over time.

However, two of the RCTs in this review suggested that rebound hypercoagulability causes most of the rebound period recurrences rather than the above alternative explanation of naturally declining VTE recurrence rates over time. By protocol design, the subjects of Ridker RCT[23] had no VTE recurrences for a period of time (median, 7 weeks; range, 12 days to 2 years[30]) after discontinuing warfarin (0 VTE recurrences/408 months [253 subjects × 7 weeks/1 month = 408], 0.00% per month) before restarting low-dose VKAs for 1 month (0 VTE recurrences/253 months, 0.00% per month on warfarin). The average time from cessation of full-dose warfarin to initiation of low-dose warfarin was not reported but was likely greater than the 7-week median length of time. Consequently, 408 months without VTE recurrences is likely a low estimate. However, the subjects still had a spike of VTE recurrences after stopping warfarin the second time. This study follows the pattern of rebound VTE recurrences of the other trials (Figure 1 Ridker [2003], 8/253 VTE recurrences [1.58% per month] in the rebound period falling to 0.51% per month from > 2 months until the end of the trial; OR = 3.13 [95% CI = 1.42, 6.89] vs OR = 2.62 [95% CI = 2.19, 3.14]). The van Gogh (2007) RCT[28] involved extended treatment with the injectable anticoagulant idraparinux vs placebo with subjects recruited from a previous RCT comparing idraparinux with warfarin.[31] The placebo arm of the extended treatment protocol consisted of subjects who had previously taken 6 months of VKAs (n = 353) or idraparinux (n = 268). Figure 1 shows that the VTE recurrences of subjects following VKA withdrawal were consistent with other RCTs in this meta-analysis (10 VTE recurrences/696 rebound period months = 1.44% per month vs 11 recurrences/2972 months = 0.37% per month from > 2 months until the end of the trial, OR = 3.92, 95% CI = 1.66-9.28). Remarkably, subjects receiving placebos after idraparinux showed no significant increase in VTE events in the rebound period (2 VTE recurrences/530 rebound period months = 0.38% per month vs 5 recurrences/2260 months = 0.27% per month from > 2 months until the end of the trial, OR = 1.71, 95% CI = 0.33-8.83). Unfortunately, increased major bleeding after the discontinuation of this anticoagulant (11/268 [1.9%] vs 0/618 [0.00%] following VKA cessation), including 3 fatal intracranial bleeds, offsets the advantage of idraparinux over OACs with regard to the lack of rebound VTE recurrences.

Rebound hypercoagulability is seen with other antithrombotic drugs treating other conditions. In patients with acute coronary syndrome, serum levels of fibrinopeptide A, prothrombin fragments, and activated protein C increase sharply after discontinuation of heparin and return to baseline within 24 hours. Antithrombin III levels decrease significantly over the 24 hours after discontinuation of heparin.[32] Coincidently, a spike in myocardial infarctions and episodes of unstable angina occur within a day of discontinuing heparins.[33–36] A similar pattern of rebound adverse vascular events (acute myocardial infarction and death) has been described after the discontinuation of clopidogrel for patients with acute coronary syndromes or percutaneous coronary interventions.[37] The spikes in arterial thromboses after discontinuing heparin and antiplatelet agents suggest that clinical events related to rebound hypercoagulability are not limited to venous thromboses after discontinuation of OACs.

The strength of this study is that it comprehensively and quantitatively documents the clinical evidence for rebound hypercoagulability after OAC withdrawal in VTE subjects from RCTs. This analysis is limited by the unavailability of large RCTs to assess the rate of VTE recurrences without anticoagulation after an initial episode. The 3 published RCTs of VTE treatment with placebo or platelet inhibitor controls were too small to formulate conclusions about the rate of early recurrences of VTE without anticoagulation (total n = 126).[38–40]

For standard anticoagulation to have a favorable risk-benefit ratio, the VTE recurrence rate in the first 3-6 months without anticoagulation would need to be very high to justify the rate of adverse events (VTE recurrences + major bleeds) during the period of treatment with heparins and VKAs (0.87% per month = 0.49% per month VTE recurrences + 0.38% per month major hemorrhages, Table 2) compared with the post 2-month rebound period VTE recurrence rate (0.56% per month [248 VTE recurrences/47,142 months at risk], Table 1).

Conclusion

Increasing the duration of OAC treatment for VTE does not significantly reduce the overall adverse events. Rebound hypercoagulability accounts for about 2% of patients having recurrent VTE in the first 2 months after discontinuing OACs. RCTs evaluating the efficacy of OACs in VTE should include data for at least 2 months following OAC treatment. Trials of antithrombotic drug treatment for other indications should include data for appropriate time intervals after discontinuing the drugs.

Footnotes

Reader Comments on: Clinical Evidence for Rebound Hypercoagulability After Discontinuing Oral Anticoagulants for Venous Thromboembolism See reader comments on this article and provide your own.

Readers are encouraged to respond to the author at Dkcundiff3@verizon.net or to Peter Yellowlees, MD, Deputy Editor of The Medscape Journal of Medicine, for the editor's eyes only or for possible publication as an actual Letter in the Medscape Journal via email: peter.yellowlees@ucdmc.ucdavis.edu

References

- 1.Palareti G, Legnani C, Guazzaloca G, et al. Activation of blood coagulation after abrupt or stepwise withdrawal of oral anticoagulants – a prospective study. Thromb Haemost. 1994;72:222–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grip L, Blomback M, Schulman S. Hypercoagulable state and thromboembolism following warfarin withdrawal in post-myocardial-infarction patients. Eur Heart J. 1991;12:1225–1233. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/12.11.1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ascani A, Iorio A, Agnelli G. Withdrawal of warfarin after deep vein thrombosis: effects of a low fixed dose on rebound thrombin generation. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 1999;10:291–295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tardy B, Tardy-Poncet B, Laporte-Simitsidis S, et al. Evolution of blood coagulation and fibrinolysis parameters after abrupt versus gradual withdrawal of acenocoumarol in patients with venous thromboembolism: a double-blind randomized study. Br J Haematol. 1997;96:174–178. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1997.8752506.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Michaels L, Beamish RE. Relapses of thromboembolic disease after discontinued anticoagulant therapy. A comparison of the incidence after abrupt and after gradual termination of treatment. Am J Cardiol. 1967;20:670–673. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(67)90010-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sharland DE. Effect of cessation of anticoagulant therapy on the course of ischaemic heart disease. Br Med J. 1966;2:392–393. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.5510.392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sise HS, Moschos CB, Gauthier J, Becker R. The risk of interrupting long-term anticoagulant treatment: a rebound hypercoagulable state following hemorrhage. Circulation. 1961;24:1137–1142. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.24.5.1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hutten BA, Prins MH. Duration of treatment with vitamin K antagonists in symptomatic venous thromboembolism. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(1):CD001367. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001367.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Agnelli G, Prandoni P, Santamaria MG, et al. Three months versus one year of oral anticoagulant therapy for idiopathic deep venous thrombosis. Warfarin Optimal Duration Italian Trial Investigators. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:165–169. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200107193450302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Agnelli G, Prandoni P, Becattini C, et al. Extended oral anticoagulant therapy after a first episode of pulmonary embolism. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:19–25. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-1-200307010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Campbell IA, Bentley DP, Prescott RJ, Routledge PA, Shetty HGM, Williamson IJ. Anticoagulation for three versus six months in patients with deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism, or both: randomised trial. BMJ. 2007;334:674. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39098.583356.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Daskalopoulos ME, Daskalopoulos SS, Tzortzis E, et al. Long-term treatment of deep venous thrombosis with a low molecular weight heparin (tinzaparin): a prospective randomized trial. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2005;29:638–650. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2004.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fennerty AG, Dolben J, Thomas P, et al. A comparison of 3 and 6 weeks' anticoagulation in the treatment of venous thromboembolism. Clin Lab Haematol. 1987;9:17–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2257.1987.tb01377.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harenberg J, Jörg I, Weiss C. Incidence of recurrent venous thromboembolism of patients after termination of treatment with ximelagatran. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2006;62:173–177. doi: 10.1007/s00228-005-0076-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Holmgren K, Andersson G, Fagrell B, et al. One-month versus six-month therapy with oral anticoagulants after symptomatic deep vein thrombosis. Acta Med Scand. 1985;218:279–284. doi: 10.1111/j.0954-6820.1985.tb06125.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hull RD, Pineo GF, Brant RF, et al. Long-term low-molecular-weight heparin versus usual care in proximal-vein thrombosis patients with cancer. Am J Med. 2006;119:1062–1072. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kearon C, Gent M, Hirsh J, et al. A comparison of three months of anticoagulation with extended anticoagulation for a first episode of idiopathic venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:901–907. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199903253401201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kearon C, Ginsberg JS, Anderson DR, Kovacs MJ, Wells P, Julian JA. Comparison of 1 month with 3 months of anticoagulation for a first episode of venous thromboembolism associated with a transient risk factor. J Thromb Haemost. 2004;2:743–749. doi: 10.1046/j.1538-7836.2004.00698.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lagerstedt CI, Olsson CG, Fagher BO, Oqvist BW, Albrechtsson U. Need for long-term anticoagulant treatment in symptomatic calf-vein thrombosis. Lancet. 1985;2:515–518. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(85)90459-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Levine MN, Hirsh J, Gent M, et al. Optimal duration of oral anticoagulant therapy: a randomized trial comparing four weeks with three months of warfarin in patients with proximal deep vein thrombosis. Thromb Haemost. 1995;74:606–611. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Palareti G, Cosmi B, Legnani C, et al. D-dimer testing to determine the duration of anticoagulation therapy. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1780–1789. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa054444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pinede L, Ninet J, Duhaut P, et al. Comparison of 3 and 6 months of oral anticoagulant therapy after a first episode of proximal deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism and comparison of 6 and 12 weeks of therapy after isolated calf deep vein thrombosis. Circulation. 2001;103:2453–2460. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.20.2453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ridker PM, Goldhaber SZ, Danielson E, et al. Long-term, low-intensity warfarin therapy for the prevention of recurrent venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1425–1434. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa035029. Available at: http://content.nejm.org/cgi/content/abstract/348/15/1425 Accessed October 24, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schulman S, Lockner D, Juhlin-Dannfelt A. The duration of oral anticoagulation after deep vein thrombosis. A randomized study. Acta Med Scand. 1985;217:547–552. doi: 10.1111/j.0954-6820.1985.tb03261.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schulman S, Rhedin AS, Lindmarker P, et al. A comparison of six weeks with six months of oral anticoagulant therapy after a first episode of venous thromboembolism. Duration of Anticoagulation Trial Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:1661–1665. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199506223322501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schulman S, Granqvist S, Holmstrom M, et al. The duration of oral anticoagulant therapy after a second episode of venous thromboembolism. The Duration of Anticoagulation Trial Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:393–398. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199702063360601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schulman S, Wahlander K, Lundstrom T, Clason SB, Eriksson H, THRIVE III Investigators Secondary prevention of venous thromboembolism with the oral direct thrombin inhibitor ximelagatran. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1713–1721. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.The van Gogh Investigators. Extended prophylaxis of venous thromboembolism with idraparinux. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1105–1112. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa067703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Buller HR, Agnelli G, Hull RD, Hyers TM, Prins MH, Raskob GE. Antithrombotic Therapy for Venous Thromboembolic Disease: The Seventh ACCP Conference on Antithrombotic and Thrombolytic Therapy. Chest. 2004;126(suppl):401S–428. doi: 10.1378/chest.126.3_suppl.401S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cushman M, Glynn RJ, Goldhaber SZ, et al. Hormonal factors and risk of recurrent venous thrombosis: the prevention of recurrent venous thromboembolism trial. J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4:2199–2203. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.02140.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.The van Gogh Investigators. Idraparinux versus standard therapy for venous thromboembolic disease. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1094–1104. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa064247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Granger CB, Miller JM, Bovill EG, et al. Rebound increase in thrombin generation and activity after cessation of intravenous heparin in patients with acute coronary syndromes. Circulation. 1995;91:1929–1935. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.91.7.1929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Risk of myocardial infarction and death during treatment with low-dose aspirin and intravenous heparin in men with unstable coronary artery disease. Lancet. 1990;336:830–837. The RISC Group. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Theroux P, Ouimet H, McCans J, et al. Aspirin, heparin, or both to treat acute unstable angina. N Engl J Med. 1988;319:1105–1111. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198810273191701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Theroux P, Waters D, Lam J, Juneau M, McCans J. Reactivation of unstable angina after the discontinuation of heparin. N Engl J Med. 1992;327:141–145. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199207163270301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cohen M, Adams P, Parry G, et al. Combination antithrombotic therapy in unstable rest angina and non-Q- wave infarction in nonprior aspirin users. Primary end points analysis from the ATACS trial. Antithrombotic Therapy in Acute Coronary Syndromes Research Group. Circulation. 1994;89:81–88. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.89.1.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ho PM, Peterson ED, Wang L, et al. Incidence of death and acute myocardial infarction associated with stopping clopidogrel after acute coronary syndrome. JAMA. 2008;299:532–539. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.5.532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kakkar VV, Flanc C, O'Shea M, Flute P, Howe CT, Clarke MB. Treatment of deep-vein thrombosis–a random trial. Br J Surg. 1968;55:858. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ott P, Eldrup E, Oxholm P. The value of anticoagulant therapy in deep venous thrombosis in the lower limbs in elderly, mobilized patients. A double-blind, placebo-controlled investigation with open therapeutic guidance. Ugeskr Laeger. 1988;150:218–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nielsen HK, Husted SE, Krusell LR, Fasting H, Charles P, Hansen HH. Silent pulmonary embolism in patients with deep venous thrombosis. Incidence and fate in a randomized, controlled trial of anticoagulation versus no anticoagulation. J Intern Med. 1994;235:457–461. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.1994.tb01103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]