Introduction

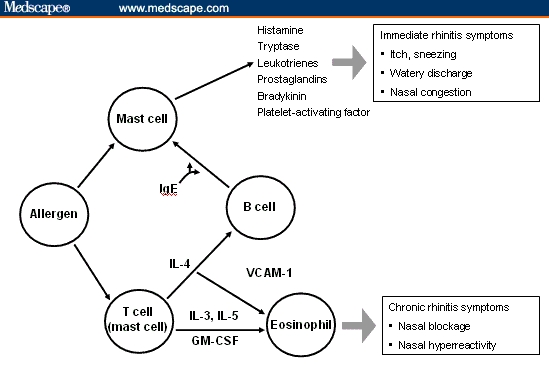

Allergic rhinitis (AR) is an inflammation of the mucous membranes lining the nose that is caused by a reaction to airborne allergens, such as pollen, mold, dust mites, and animal dander. The early-phase response is prompted by histamine released after allergen exposure and results in the acute symptoms of sneezing; nasal pruritus; rhinorrhea; nasal congestion; and ocular itching/burning, redness, and tearing/watering. Some hours later, the late-phase reaction occurs and is marked by activation of eosinophils and Th2 lymphocytes, leading to chronic nasal congestion, postnasal drip, and nasal hyperreactivity (Figure 1).[1–3]

Figure 1.

Mechanism of allergic rhinitis.[1]

IgE = immunoglobulin E; IL = interleukin; GM = granulocyte macrophage; CSF = cerebrospinal fluid; VCAM = vascular cell adhesion molecule.

Republished with permission from Scadding et al.[1]

Allergic rhinitis causes significant discomfort and impairs work productivity, school performance, social interactions, and sleep.[4–6] Annual direct costs due to AR have been estimated to be €1.29 billion in Europe[7] and $4.5 billion in the United States.[8] Patients say that AR significantly reduces their quality of life (QoL).[9,10] According to the results of one survey, AR is associated with more lost work productivity than are other chronic conditions, including depression, arthritis, migraine, diabetes, coronary heart disease, and asthma.[10–12]

The management of AR may involve allergen avoidance, pharmacotherapy, allergen-specific immunotherapy, or a combination of all three. Pharmacologic options include intranasal corticosteroids (INSs), oral and intranasal antihistamines, intranasal chromones, oral and intranasal decongestants, oral and intranasal anticholinergic agents, and antileukotrienes.[13] The Allergic Rhinitis and Its Impact on Asthma (ARIA) guidelines[13] and the European Academy of Allergology and Clinical Immunology (EAACI) consensus statement[14] note that INSs are a highly effective first-line treatment for moderate/severe or persistent AR because they relieve symptoms to a greater degree than other classes of drugs and are especially effective in controlling nasal congestion. The anti-inflammatory properties of INSs may explain their strong effect on clinical symptoms.

Intranasal corticosteroids are safe and well tolerated. When administered at indicated doses, most INSs do not lead to the systemic adverse events associated with oral corticosteroids, including suppression of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis or impairment of bone growth.[15–19] Local side effects of INSs are generally mild to moderate, similar in incidence to those of placebo, and include headache, irritation of the nose and throat, sneezing, crusting, transient dryness, and epistaxis. Side effects are often limited to the start of treatment; occasionally they persist, and in such cases a change in formulation or delivery system may be required.[15,20]

Intranasal corticosteroids may possess quite different sensory attributes, such as odor, taste, irritation, and drying effect, and patients often prefer the attributes of one preparation over another.[21] Patient surveys reveal attitudes toward treatment of AR that may contribute to a better understanding of how patients develop a preference for a particular therapy or class of therapy.

We identified and compared surveys that investigated patient preference in AR therapy. The topics covered included comparative burden of the symptoms of AR on patients; impact of symptoms on QoL; patterns of AR medication use; and, finally, patients' satisfaction with their AR treatments, focusing on attributes of AR medications in general, and attributes of INSs specifically. These surveys were evaluated to reveal commonalities and patterns in each of the domains listed above.

Methods

This review analyzes patient surveys that involved healthcare providers and 10,646 patients with AR in 6 countries. Surveys dealing with asthma and review articles with no original data were excluded. MEDLINE was searched for all English-language journal articles from 1997-2007 containing the expressions “questionnaire” and “allergic rhinitis” in any text field, including key words. The selection was then narrowed to surveys of patient choices and attitudes toward AR therapy. Bibliographies of primary and review articles were searched for additional articles on patient preferences in AR treatment. The 5 surveys selected for review are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Surveys Assessed

| Survey Name | Countries | Topics | Population | Design |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allergies in America[22] (Survey 1)a | United States | Symptoms; seasonality; impact of symptoms; medication use; effectiveness of and satisfaction with medication; side effects | 2500 adults diagnosed with AR; had nasal allergy symptoms or had been treated for them in past 12 months; in parallel, 400 healthcare providers | 34.8-minute interview of AR sufferers; 19.4-minute interview of healthcare providers |

| Understanding the Dynamics Surrounding Allergy Suffering and Treatment[23] (Survey 2)b | France, Germany, Italy, Spain, United Kingdom, United States | Symptoms; impact of symptoms; use of healthcare providers; treatments used; ideal attributes of AR therapy | 3635 adults with indoor allergies, outdoor allergies, pet allergies, or urticaria | 25-minute questionnaire |

| Impact of Nasal Congestion Among Allergic Rhinitis Sufferers[24] (Survey 3)c | United States | Symptoms; impact of nasal congestion; medication use; use of healthcare; effect on quality of life; treatment effectiveness; knowledge of nasal steroids; awareness of MFNS | 2002 adults with AR or primary caregivers of a child with AR; nasal congestion present | Online interview of Roper national panel 25-minute questionnaire with 43 questions relating to AR |

| Impact of Morning Symptoms on Allergy Sufferers[25] (Survey 4)c | United States | Morning AR symptoms; impact of symptoms; medication use; effectiveness of medication | 1000 adults with physician-diagnosed AR balanced to represent the US population | Online interview of Roper national panel |

| Claims Evaluation Survey[26] (Survey 5)d | United States | Ease of use of medication; sensory attributes | 1544 MFNS users; subgroups included children, the elderly, and patients with arthritis | Online panel |

AR = allergic rhinitis; MFNS = mometasone furoate nasal spray.

Survey sponsored by ALTANA Pharma US, Inc. (Florham Park, NJ, USA) and conducted by Schulman, Ronca & Bucuvalas, Inc. (New York, NY, USA).

Survey commissioned by Schering-Plough (Kenilworth, NJ, USA) and conducted by Forbes Consulting Group (Lexington, MA, USA).

Survey commissioned by Schering-Plough and conducted by the Roper Public Affairs Group of NOP World (New York, NY, USA).

Survey commissioned by Schering-Plough and conducted by Synovate (the market research arm of Aegis Group plc [London, England]).

Patient Surveys Regarding Allergic Rhinitis Symptoms and Treatment Preferences

Survey 1: Allergies in America. The landmark Allergies in America survey, conducted in 2006, is the largest and most comprehensive national survey to date. A total of 2500 adult patients with AR who had experienced nasal allergy symptoms or received prescription medication for nasal allergies within the previous 12 months were surveyed.[22] A parallel survey was conducted among 400 healthcare providers.

Survey 2: Understanding the Dynamics Surrounding Allergy Suffering and Treatment. A multinational survey (United States and 5 European countries) was conducted in 2005 to gain a deeper understanding of attitudes to and perceptions of allergy symptoms and their treatments.[23] Over 3600 respondents self-identified as having outdoor (hay fever, weeds, grass, pollen, trees), indoor (dust, dust mites, molds), or pet allergies or urticaria were enrolled. Persons who primarily had food, insect, or medication allergies were excluded.

Survey 3: Impact of Nasal Congestion Among Allergic Rhinitis Sufferers. An Internet survey conducted by the Roper Public Affairs Group of NOP World in 2004 assessed the effects of nasal congestion on QoL and work productivity in 2002 patients/caregivers of children (aged ≤18 years) with AR.[24] Participants were part of the NOP World panel of consumers who had been screened by a questionnaire to identify those with a history of AR symptoms. Data were weighted for age, gender, education, and region to balance them proportionally to the US census population.

Survey 4: Impact of Morning Symptoms on Allergy Sufferers. This Internet survey conducted in 2005 by the Roper Organization assessed the impact of morning symptoms in 1000 adults with physician-diagnosed AR.[25] Respondents were selected on a random stratified basis, with the sample balanced to reflect the US population by census division, ethnicity, gender, and presence of children living at home. Data were weighted for gender on the basis of previous reports of the adult population with AR.

Survey 5: Claims Evaluation Survey. In 2006, 1544 persons formed a random sample of preidentified mometasone furoate nasal spray (MFNS) users. Respondents viewed 5 claims about product attributes and ease of use of MFNS and were asked to select the most and least important. Subgroups included pediatric and elderly users and patients with arthritis.[26]

Results

Commonalities and notable differences were both seen in the surveys (Table 1). Table 2 reports results from 4 surveys suggesting that the symptoms of AR need to be more effectively managed.[22–25] Table 3 presents important attributes of AR treatments as perceived by patients.[23,25] Table 4 contains statistics rating degrees of patient satisfaction with AR treatment.[22,24] Finally, Table 5 compares the experiences of patients being treated for AR with INSs in Surveys 1, 2, 3, and 5.[22–24, 26]

Table 2.

| Symptom Category | Finding | Respondents, % | Survey |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal/sinus congestiona | Nasal congestion extremely/moderately bothersome | 78% | 1 |

| Nasal congestion most bothersome condition | 48% adults58% children | 3 | |

| Congestion described as “severe” | 40% | 1 | |

| Congestion affects those employed at work | >50% | ||

| Sleep disturbance | Symptoms make it difficult to fall asleep | 26%-47% | 2 |

| Nasal congestion disturbs sleep/makes falling asleep difficult | >80% | 3 | |

| Morning symptoms | Symptoms most severe in morning | ∼50% | 2 |

| Symptoms experienced on wakening/in morning | 83% | 4 | |

| Morning symptoms extend through rest of day | ∼100% | 3 | |

| Emotional effects | Frequently or sometimes “miserable” because of AR | 65% | 1 |

| Disease makes patient feel tired | 80% | 1 |

AR = allergic rhinitis.

Sneezing, rhinorrhea, and itchy/watery eyes were the most commonly reported symptoms in Survey 2 across all countries.

Table 3.

| Treatment Attributes | Survey |

|---|---|

| 24-hour relief | 2, 4 |

| Fast acting | 2, 4 |

| Allows waking up symptom free/symptoms under control | 2, 4 |

| Effective medicine | 2 |

| Nondrowsy/does not affect alertness, focus | 2, 4 |

| No undesirable side effects | 2 |

| Gives user sense of control of AR | 2 |

| Effective until time for next dose | 4 |

AR = allergic rhinitis.

Table 4.

| Finding | Respondents, % | Survey |

|---|---|---|

| Satisfied with current medicationa | 62% | 3 |

| Very satisfied with current medication | 13% | 3 |

| Satisfied with INS treatment | 75% (35% very; 40% somewhat) | 1 |

| Very satisfied with disease managementb | 58% | 1 |

AR = allergic rhinitis; INS = intranasal corticosteroid.

Results were similar regardless of whether the patients were using an INS or another form of treatment.

In contrast, nearly all healthcare providers said that their patients were either very satisfied or somewhat satisfied with the management of their disease.

Table 5.

| Category | Experience | Respondents, % | Survey |

|---|---|---|---|

| Satisfactiona | Very satisfied with INS treatment | 35% | 1 |

| Satisfied with INS treatment | 62% | 3 | |

| Reasons not to use | Believe INSs lose effectiveness if used too much | 34-61% (France, Germany, Italy, Spain) | 2 |

| Most important benefit | Prevention of nasal congestion | 38% | 3 |

| Survey 5b | |||

| Most important ease-of-use attributes |

|

All categories of patients chose these as the most important attributes | |

INSs = intranasal corticosteroids.

Of those dissatisfied with another current therapy, 28% said they would try INSs in the future.

Comprised preidentified mometasone furoate nasal spray users.

Burden of Allergic Rhinitis Symptoms

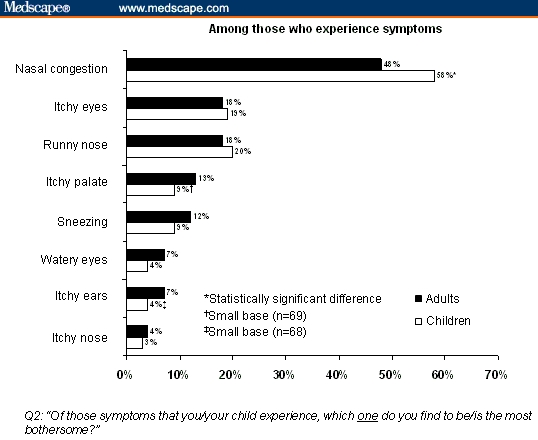

Table 2 shows that patients perceive the need for more effective treatment of AR.[22–25] Across surveys, respondents said nasal and sinus congestion, sleep disturbance, morning symptoms, and the emotional effects of AR impaired QoL. In Survey 3, nasal congestion was rated as the most bothersome symptom by 48% of adult respondents and 58% of children (Figure 2).[24] Congestion was the symptom most likely to trigger a visit to a physician, regardless of whether it was mild, moderate, or severe, and it was perceived to be the most difficult symptom to manage (47% of adults and 60% of children).[27]

Figure 2.

Allergic rhinitis symptoms rated as “most bothersome.”[24]

Republished with permission from Shedden.[24]

Survey 3 confirmed earlier findings that nasal congestion has a substantial impact on QoL and sleep.[24, 28–30] More than 80% of respondents reported that nasal congestion led to sleep disturbances, including nighttime awakening (51% of adults and 49% of children) and difficulty in falling asleep (48% of adults and 49% of children).[24] Most respondents who were employed stated that congestion affected them at their workplace, primarily due to inability to concentrate or reduced productivity. Similar effects were reported in school-age children[24,30]; Walker and colleagues[30] found that AR symptoms are sufficiently bothersome to have a detrimental effect on teenagers' performance on school examinations.

In Survey 4, 83% of respondents indicated that they experienced symptoms either on awakening or at other times in the morning. Morning symptoms affected nearly all patients for the rest of the day.[25]

In Survey 1, 78% of respondents reported nasal congestion as being extremely or moderately bothersome and 40% described their congestion as severe. Emotional effects of AR were widespread, with about 65% reporting being sometimes or frequently irritable or miserable. Moreover, AR made 80% of respondents sometimes or frequently tired.[22]

Important Treatment Characteristics

Table 3 shows what patients identify as the most important characteristics of treatments. The most important attributes of a medication in both the United States and Europe included “effective medicine,” “no undesirable side effects,” “lets me stay alert and focused,” “lets me wake up symptom free,” “fast acting,” and “puts me in control of my allergies.”[23,25] Patients who treated their symptoms with INSs were consistently more likely to give high rankings to “full 24-hour relief” and “provides all-day relief into the next morning” than nonusers.[23]

Characteristics of allergy medications rated as important in the United States included 3 features of sustained efficacy: “maintains its effectiveness to the designated time you are to take another dose” (mentioned by 68% of respondents), “lets you wake up with symptoms under control” (63%), and “provides relief all day and into next morning” (62%). Other important characteristics were “experience relief within an hour after taking medication” and “nondrowsy.”[25]

How Satisfied Are Patients With Treatments?

Table 4 depicts patient satisfaction with AR treatments, which was similar for INS users and nonusers.[22,24] Among the nonusers, 17% stated that they would probably or definitely try INS therapy in the future; among those who were dissatisfied or very dissatisfied with current treatment, the percentage who would probably or definitely try INS therapy rose to 28%.[27] When the question was rephrased to include a description of the advantages of INSs in preventing, delaying, or reducing nasal congestion or its severity, the percentage of nonusers who said they would probably try an INS increased to 43%.[24,27]

Survey 1 also examined satisfaction with medication and disease management.[22] Of the 860 respondents who had asked a doctor to change their allergy medication, 66% reported lack of effectiveness as the reason for the change and 21% cited side effects. A total of 53% of respondents reported that their medication lost its effectiveness at least once with continued use. Many respondents had stopped taking a prescription nasal allergy medication, mostly because of lack of or reduced effectiveness. The survey did not identify which classes of medication were associated with specific side effects. A total of 58% of those who had seen a healthcare provider about allergies in the past year described themselves as very satisfied with disease management. In contrast, nearly all healthcare providers (primary care physicians [PCPs], allergists, otolaryngologists, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants) said their patients were very or somewhat satisfied with disease management.[22]

Patients had lower expectations of AR therapy than did their physicians.[22] Only 22% of patients agreed with the statement “frequent nasal allergy symptoms can be prevented in most cases,” compared with 38% of PCPs and 58% of otolaryngologists. A total of 15% of patients said there are no truly effective treatments for nasal allergies, a perception shared only by 1% to 3% of healthcare providers. Both patients and providers said better patient education is needed about the condition and its treatment.[22]

Patient Experiences With INS Treatment

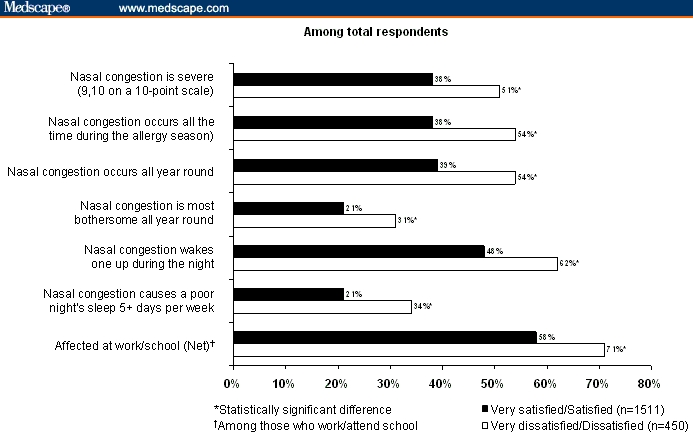

Table 5 reports patient experiences in treating AR with INSs. In Survey 1, 35% of the patients who used INSs were very satisfied and 40% were somewhat satisfied. However, nearly half of patients taking INSs reported that the medication lost effectiveness before the next dose (no follow-up questions were asked to gauge why patients had this perception).[22] In Survey 3, in most instances, patients who used INSs combined them with other AR drug therapies: only 2% to 3% treated their symptoms with INS monotherapy. Respondents with severe nasal congestion were less likely to rely on over-the-counter treatments alone.[27] Most respondents (62%) rated themselves as satisfied with their medication, but only 13% described themselves as very satisfied.[24] Those who were dissatisfied or very dissatisfied were significantly more likely to have sleep disturbances, severe and/or prolonged congestion, and to be affected at work or school (Figure 3).[24,27]

Figure 3.

Dissatisfaction with management of allergic rhinitis symptoms leads to poorer quality of life.[27]

Republished with permission from Roper Public Affairs and Media.[27]

In Survey 2, relatively few respondents (3% to 10%) thought that INSs were unsafe; however, 34% to 61% of those in France, Germany, Italy, and Spain did not use INSs because they believed the drugs would lose their effectiveness if used too much.[23] Reasons cited for not using INSs varied widely by country and included “satisfaction with current medication” and the effects of administering some INSs, such as “sprays dripping down throat,” “dislike of taste,” “dislike of putting spray nozzle in the nose,” and “burning/stinging in the nose.” Published findings from clinical trials confirm that sensory attributes of INSs are important to patients, who indicate that they prefer scent- and alcohol-free formulations.[31–34]

Discussion

The surveys and clinical trials reviewed here investigated patients' symptomatology and experiences with AR treatment among 11,046 patients and healthcare providers in 9 countries. Patients with AR often reported limited success in controlling symptoms with pharmacologic therapy.

Survey 3 found that most users of nasal sprays also use concomitant oral therapy to relieve symptoms of AR.[24] The treatment algorithm developed by the ARIA Working Group and the EAACI consensus statement outline INS as a first-line option for moderate-to-severe and/or persistent disease.[13,14] The Joint Task Force on Practice Parameters in Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology concluded that INSs are the most effective medication class for controlling AR symptoms.[35] However, the surveys reviewed here have shown that only a minority of patients with AR use this form of therapy. For example, in Survey 3 only 30% of respondents with severe nasal congestion and 21% of those with moderate nasal congestion used INSs (either alone or combined with another medication).[24] Oral medications were the preferred form of therapy among respondents in the Survey 2.[23] Systematic reviews of 16[36] and 9[37] clinical trials comparing INSs and H1 antihistamines for treatment of AR symptoms concluded that INSs provide significantly better improvement of nasal symptoms, while no difference was shown between the 2 treatments in improving ocular allergy symptoms. Data from several clinical trials have not shown combination therapy with INSs and antihistamines to be better than INS monotherapy in relieving AR symptoms.[38–40] However, patients with persistent symptoms not adequately controlled with monotherapy may benefit from a concomitant medication (eg, an antihistamine).[13]

Misperceptions about prescription nasal sprays held by both users and nonusers appear to be at least partly responsible for the stated preference for oral medication. In the 5 European countries in Survey 2, more than one third of nonusers thought that nasal sprays lose effectiveness with continued use.[23] This perception may be due to rhinitis medicamentosa, or “rebound congestion,” caused by chronic use of nasal decongestants but not by INSs.[41] Hyland and Ståhl[42] noted similar perceptions among asthma patients, attributing them to fear or misunderstanding: In a survey conducted in Germany, Spain, and the United Kingdom, 65.6% of respondents agreed that chronic use of asthma medication would lead to tolerance and a need to increase dosage to maintain the same level of symptom control.[42]

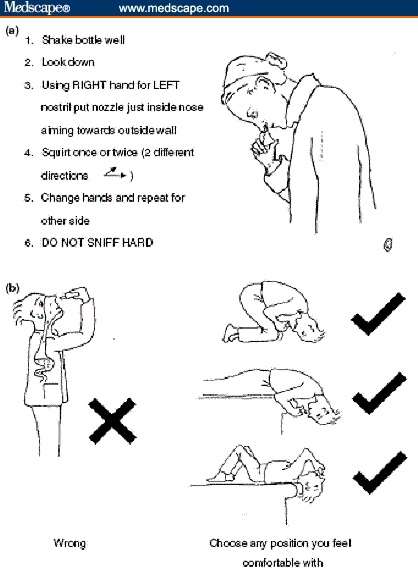

Despite clinical data demonstrating relief of AR symptoms for a period of 12 to 48 hours after INS dosing,[14] patients have reported a perceived loss of effectiveness over time. Several factors influence successful management of AR, including correct administration technique and patient acceptance and adherence to medication. Many patients with poor nasal inhalation technique sniff or snort the INS when applied to the nose, which causes immediate taste or sensation of the INS in the back of the throat. It is important that healthcare providers demonstrate the correct technique to all patients (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Correct procedure for the application of nasal sprays (a) and nasal drops (b).[1]

Republished with permission from Scadding et al.[1]

Patient preference data show that patients' opinions about the sensory attributes of INSs directly affect adherence to treatment. Patients' clear preferences for low odor and aftertaste have led to development of alcohol- and odor-free formulations of INSs.[31–34] Patients have indicated that they would be more likely to adhere to a treatment regimen if the healthcare provider prescribed the patient-preferred formulation.[32]

The surveys revealed several areas in which better healthcare provider-patient communication could potentially improve patient outcomes. Survey 1 found that patients have lower expectations for symptom control than do healthcare providers. Responses from providers suggested that they may underestimate patients' perceptions of the limitations of allergy treatment. Most indicated that nearly all of their patients were somewhat satisfied or very satisfied with therapy, but patients often reported inadequate symptom control.[22] This suggests a need for improved communication between patients and providers, perhaps by means of QoL instruments.

The potential effect of patient education was apparent from Survey 3, in that many more respondents were willing to try INSs when their advantages in treating nasal congestion were better elucidated.[24] Patient education will probably improve as physician and patient awareness of the impact of AR on patients increases.[43] In addition, improvement in diagnostic processes by physicians and differentiation between allergic and nonallergic rhinitis may serve to further this process.[44] By fostering communication with patients to identify their expectations and preferred sensory attributes, healthcare providers have the opportunity to improve patient satisfaction with and outcomes of treatment.

A few limitations of this review should be noted. The data were not amenable to meta-analysis, owing to differences in study design and outcomes. Most surveys relied on patient recall and were not subject to confirmation (eg, with prescription bottles, medical examination, or skin-prick testing for allergen sensitivity). Despite these limitations, the findings provide valuable insight into the burden of AR from patients' perspectives and patients' attitudes toward different treatment options, broadening the understanding of how AR management might be improved.

Conclusion

This review of results from patient surveys provides additional insight into the burden of AR from the patient's perspective and on patients' attitudes toward different treatment options. The data also confirm that AR symptoms need to be more effectively managed.

Most patients with AR, including those with moderate-to-severe congestion, prefer taking oral prescription and over-the-counter antihistamines. Despite expert panels' recommendations for use as first-line therapy in AR,[13,14] patients' perceptions of INSs, coupled with preferences for specific sensory attributes, have limited the medications' acceptability. Patient preference data led to the development of scent- and alcohol-free INS formulations. Improved patient education, including nasal inhalation technique, could lead to improved adherence to treatment and better AR management.

Acknowledgments

Editorial assistance was provided by Patricia C. Abramo and was funded by Schering-Plough.

Funding Information

Financial support for this study was provided by Schering-Plough.

Footnotes

Reader Comments on: Patient Adherence to Allergic Rhinitis Treatment: Results From Patient Surveys See reader comments on this article and provide your own.

Readers are encouraged to respond to the author at erkka.valovirta@terveystalo.com or to Peter Yellowlees, MD, Deputy Editor of The Medscape Journal of Medicine, for the editor's eyes only or for possible publication as an actual Letter in the Medscape Journal via email: peter.yellowlees@ucdmc.ucdavis.edu

Contributor Information

Erkka Valovirta, Pediatrics and Pediatric Allergology, Turku Allergy Center, Turku, Finland Author's email: erkka.valovirta@terveystalo.com.

Dermot Ryan, Woodbrook Medical Centre, Loughborough, England; Primary Care Respiratory Medicine, Department of General Practice and Primary Care, University of Aberdeen, Scotland.

References

- 1.Scadding GK, Durham SR, Mirakian R, et al. BSACI guidelines for the management of allergic and non-allergic rhinitis. Clin Exp Allergy. 2008;38:19–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2007.02888.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dykewicz MS, Fineman S, Skoner DP, et al. Diagnosis and management of rhinitis: complete guidelines of the Joint Task Force on Practice Parameters in Allergy, Asthma and Immunology. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 1998;81:478–518. doi: 10.1016/s1081-1206(10)63155-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Skoner DP. Allergic rhinitis: definition, epidemiology, pathophysiology, detection, and diagnosis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;108:S2–S8. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.115569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Demoly P, Allaert F-A, Lecasble M, PRAGMA ERASM, a pharmacoepidemiologic survey on management of intermittent allergic rhinitis in every day general medical practice in France. Allergy. 2002;57:546–554. doi: 10.1034/j.1398-9995.2002.t01-1-13370.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vuurman EFPM, van Veggel LMA, Uiterwijk MMC, Leutner D, O'Hanlon JF. Seasonal allergic rhinitis and antihistamine effects on children's learning. Ann Allergy. 1993;71:121–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Juniper EF, Guyatt GH. Development and testing of a new measure of health status for clinical trials in rhinoconjunctivitis. Clin Exp Allergy. 1991;21:77–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.1991.tb00807.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.The UCB Institute of Allergy: European Allergy White Paper. Chapter 5. Socio-economic costs of allergic diseases. Available at: http://www.theucbinstituteofallergy.com/ioaImages/247_13_CH_5_tcm75-5864.pdf Accessed June 7, 2007.

- 8.American Academy of Allergy Asthma & Immunology. The Allergy Report, Volume II: Diseases of the atopic diathesis. Available at: http://www.aaaai.org/ar/volume2.pdf Accessed November 2, 2007.

- 9.Leynaert B, Neukirch C, Liard R, Bousquet J, Neukirch F. Quality of life in allergic rhinitis and asthma: a population-based study of young adults. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162:1391–1396. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.162.4.9912033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scadding GK, Richards DH, Price MJ. Patient and physician perspectives on the impact and management of perennial and seasonal allergic rhinitis. Clin Otolaryngol. 2000;25:551–557. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2273.2000.00417.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lamb CE, Ratner PH, Johnson CE, et al. Economic impact of workplace productivity losses due to allergic rhinitis compared with select medical conditions in the United States from an employer perspective. Curr Med Res Opin. 2006;22:1203–1210. doi: 10.1185/030079906X112552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Demoly P, Crampette L, Daures JP. National survey on the management of rhinopathies in asthma patients by French pulmonologists in everyday practice. Allergy. 2003;58:233–238. doi: 10.1034/j.1398-9995.2003.00051.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bousquet J, van Cauwenberge P, Khaltaev N, the Workshop Expert Panel Allergic Rhinitis and its Impact on Asthma (ARIA) in collaboration with the World Health Organization. Executive summary of the Workshop Report. Allergy. 2002;57:841–855. doi: 10.1034/j.1398-9995.2002.23625.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van Cauwenberge P, Bachert C, Passalacqua G, et al. Consensus statement on the treatment of allergic rhinitis. Allergy. 2000;55:116–134. doi: 10.1034/j.1398-9995.2000.00526.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Salib RJ, Howarth PH. Safety and tolerability profiles of intranasal antihistamines and intranasal corticosteroids in the treatment of allergic rhinitis. Drug Saf. 2003;26:863–893. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200326120-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Allen DB. Do intranasal corticosteroids affect childhood growth? Allergy. 2000;55(suppl 62):15–18. doi: 10.1034/j.1398-9995.2000.00704.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim KT, Rabinovitch N, Uryniak T, Simpson B, O'Dowd L, Casty F. Effect of budesonide aqueous nasal spray on hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis function in children with allergic rhinitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2004;93:61–67. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)61448-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patel P, Ratner P, Clements D, Wu W, Philpot E. Twenty-four serum and urine cortisol data support hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical axis safety of once-daily fluticasone furoate nasal spray 110 mcg in adolescents and adults with perennial allergic rhinitis. Allergy. 2007;62(suppl 83):226. Abstract 623. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gradman J, Caldwell M, Wolthers O. Comparison of short term lower leg growth in children treated with fluticasone furoate nasal spray and vehicle placebo spray. Allergy. 2007;62(suppl 83):226–227. Abstract 624. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zitt M, Kosoglou T, Hubbell J. Mometasone furoate nasal spray: a review of safety and systemic effects. Drug Saf. 2007;30:317–326. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200730040-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meltzer EO. Intranasal steroids: managing allergic rhinitis and tailoring treatment to patient preference. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2005;26:445–451. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Allergies in America: A Landmark Survey of Nasal Allergy Sufferers. Available at: http://www.myallergiesinamerica.com Accessed June 7, 2007.

- 23.Forbes Consulting Group. Understanding the Dynamics Surrounding Allergy Suffering and Treatment. Lexington, MA: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shedden A. Impact of nasal congestion on quality of life and work productivity in allergic rhinitis: findings from a large online survey. Treat Respir Med. 2005;4:439–446. doi: 10.2165/00151829-200504060-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Long AA. Findings from a 1000-patient Internet-based survey assessing the impact of morning symptoms on individuals with allergic rhinitis. Clin Ther. 2007;29:342–351. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2007.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Synovate. Nasonex Claims Evaluation Final Report. December 2006.

- 27.Roper Public Affairs and Media. Impact of Nasal Congestion Among Allergic Rhinitis Sufferers. 2004.

- 28.Kakumanu S, Glass C, Craig T. Poor sleep and daytime somnolence in allergic rhinitis: significance of nasal congestion. Am J Respir Med. 2002;1:195–200. doi: 10.1007/BF03256609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Craig TJ, Teets S, Lehman EB, Chinchilli VM, Zwillich C. Nasal congestion secondary to allergic rhinitis as a cause of sleep disturbance and daytime fatigue and the response to topical nasal corticosteroids. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1998;101:633–637. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(98)70171-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Walker S, Khan-Wasti S, Fletcher M, Cullinan P, Harris J, Sheikh A. Seasonal allergic rhinitis is associated with a detrimental effect on examination performance in United Kingdom teenagers: case-control study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120:381–387. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meltzer EO, Bardelas J, Goldsobel A, Kaiser H. A preference evaluation study comparing the sensory attributes of mometasone furoate and fluticasone propionate nasal sprays by patients with allergic rhinitis. Treat Respir Med. 2005;4:289–296. doi: 10.2165/00151829-200504040-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bachert C, El-Akkad T. Patient preferences and sensory comparisons of three intranasal corticosteroids for the treatment of allergic rhinitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2002;89:292–297. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)61957-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lumry W, Hampel F, LaForce C, Kiechel F, El-Akkad T, Murray JJ. A comparison of once-daily triamcinolone acetonide aqueous and twice-daily beclomethasone dipropionate aqueous nasal sprays in the treatment of seasonal allergic rhinitis. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2003;24:203–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stokes M, Amorosi SL, Thompson D, Dupclay L, Garcia J, Georges G. Evaluation of patients' preferences for triamcinolone acetonide aqueous, fluticasone propionate, and mometasone furoate nasal sprays in patients with allergic rhinitis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;131:225–231. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2004.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dykewicz MS, Fineman S. Executive summary of joint task force practice parameters on diagnosis and management of rhinitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 1998;81:463–468. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)63152-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weiner JM, Abramson MJ, Puy RM. Intranasal corticosteroids versus oral H1 receptor antagonists in allergic rhinitis: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. BMJ. 1998;317:1624–1629. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7173.1624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yáñez A, Rodrigo GJ. Intranasal corticosteroids versus topical H1 receptor antagonists for the treatment of allergic rhinitis: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2002;89:479–484. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)62085-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barnes ML, Ward JH, Fardon TC, Lipworth BJ. Effects of levocetirizine as add-on therapy to fluticasone in seasonal allergic rhinitis. Clin Exp Allergy. 2006;36:676–684. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2006.02478.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nielson LP, Mygind N, Dahl R. Intranasal corticosteroids for allergic rhinitis: superior relief? Drugs. 2001;61:1563–1579. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200161110-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Di Lorenzo G, Pacor ML, Pellitteri ME, et al. Randomized, placebo-controlled trial comparing fluticasone aqueous nasal spray in mono-therapy, fluticasone plus cetirizine, fluticasone plus montelukast and cetirizine plus montelukast for seasonal allergic rhinitis. Clin Exp Allergy. 2004;34:259–267. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2004.01877.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Graf P. Rhinitis medicamentosa: a review of causes and treatment. Treat Respir Med. 2005;4:21–29. doi: 10.2165/00151829-200504010-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hyland ME, Ståhl E. Asthma treatment needs: a comparison of patients' and health care professionals' perceptions. Clin Ther. 2004;26:2141–2153. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2004.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ryan D, Grant-Casey J, Scadding G, Pereira S, Pinnock H, Sheikh A. Management of allergic rhinitis in UK primary care: baseline audit. Prim Care Respir J. 2005;15:204–209. doi: 10.1016/j.pcrj.2005.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ryan D, van Weel C, Bousquet J, et al. Primary care: the cornerstone of diagnosis of allergic rhinitis. Allergy. 2008;63:981–989. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2008.01653.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]