Abstract

Nerve root compression produces persistent behavioral sensitivity in models of painful neck injury. This study utilized degradable poly(ethylene glycol) hydrogels to deliver glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) to an injured nerve root. Hydrogels delivered ∼98% of encapsulated GDNF over 7 days in an in vitro release assay without the presence of neurons and produced enhanced outgrowth of processes in cortical neural cell primary cultures. The efficacy of a GDNF hydrogel placed on the root immediately after injury was assessed in a rat pain model of C7 dorsal root compression. Control groups included painful injury followed by: (1) vehicle hydrogel treatment (no GDNF), (2) a bolus injection of GDNF, or (3) no treatment. After injury, mechanical allodynia (n=6/group) was significantly decreased with GDNF delivered by the hydrogel compared to the three injury control groups (p<0.03). The bolus GDNF treatment did not reduce allodynia at any time point. The GDNF receptor (GFRα-1) decreased in small, nociceptive neurons of the affected dorsal root ganglion, suggesting a decrease in receptor expression following injury. GDNF receptor immunoreactivity was significantly greater in these neurons following GDNF hydrogel treatment relative to GDNF bolus treated and untreated rats (p<0.05). These data suggest efficacy for degradable hydrogel delivery of GDNF and support this treatment approach for nerve root-mediated pain.

Introduction

Chronic neck pain affects as many as 71% of adults at some point during their lives.1,2 Painful cervical spine injuries can result from non-physiologic loading of the neck as occurs in recreational accidents and contact sports,3,4 when nerve roots can be compressed.5 Nerve root compression induces persistent behavioral hypersensitivity in rat models of radiculopathy, in which painful responses are elicited in the affected dermatome by stimulation that does not normally provoke pain (mechanical allodynia).6-9 Further, hypersensitivity to a stimulus has been used as a sensitive clinical indicator of pain.10 Compression of primary afferent neurons also produces increased neuronal excitability, ectopic axonal firing, Wallerian degeneration, endoneurial edema, inflammatory responses, and decreased spinal substance P.7,8,11-16

Current treatments for neuropathic pain include opioids, non-steroidal anti-inflammatories, antagonists to ion channels, neuropeptides, cytokines, and trophic factors to promote cell survival and regeneration.17-23 Neurotrophic factors can prevent secondary neuronal degeneration and reduce spontaneous firing. In particular, glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) has analgesic effects and modulates nociceptive signaling by altering sodium channel subtype expression and reducing aberrant A-fiber sprouting into the cord.18,19,24-26 However, in neuropathic pain models, GDNF is decreased after injury which may initiate nocicieptive mechanisms.19,50 GDNF also upregulates somatostatin, directly opposing the nociceptive action of substance P.24,26,27 GDNF is a member of the TGF-β superfamily and binds the GDNF family receptor (GFR)α-1, initiating an intracellular MAP kinase cascade that enhances neuronal survival via inhibition of apoptosis proteins.20 Continuous GDNF delivery prevents behavioral and electrophysiological abnormalities in neuropathic pain and partially reverses increased GFRα-1 in large DRG neurons if administered by an osmotic minipump.18,28 However, implantation of osmotic minipumps,18,22 repeated injections29 or gene therapy30 all have inherent clinical limitations.

The delivery of neurotrophic factors from degradable polymers, such as hydrogels, obviates clinical issues, and may provide significant analgesia compared to an equivalent dosing in a single injection treatment. A variety of studies have utilized hydrogel matrices for tissue engineering and drug delivery,31-33 but few have applied trophic factor release from hydrogels in an in vivo model of neuronal injury.34 Degradable hydrogels can be designed for a range of release profiles, based on crosslinking density, susceptibility to degradation, and hydrophilicity.35,36 Degradable poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) has been used to deliver neurotrophins and improve neurite outgrowth from retinal explants.37 Trophic factor delivery in vivo to injured neural tissue significantly increased fiber sprouting and motor recovery for many hydrogels and trophic factor systems, including PEG.34,38-40 However, no study has compared behavioral hypersensitivity following neural injury for controlled release of GDNF from a hydrogel system versus a single injection of an equivalent quantity of GDNF.

In our model of dorsal root compression, transient loading of the root produces behavioral hypersensitivity that persists for 7 days.15,41 In other pain studies, neural compression reduces GDNF-immunoreactivity in the dorsal root ganglion (DRG),19,50 induces axonal degeneration and macrophage infiltration in the dorsal root, and significantly decreases spinal neuropeptides.41 No study has investigated controlled release of GDNF from degradable PEG hydrogels for reducing behavioral hypersensitivity and restoring GDNF-immunoreactivity in the DRG following painful dorsal root injury.

Materials and Methods

Hydrogel Formulation & GDNF Bioassay

In vitro assays established the temporal release and bioactivity of degradable PEG-encapsulated GDNF prior to in vivo implantation. The hydrogel was formed from a macromer of acrylated polylactic acid and PEG (PLA-b-PEG-b-PLA, Polysciences, Warrington, PA).34-36 The macromer was fabricated from 4kDa PEG (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) capped with ∼2.7 lactic acid units per side and acrylated to ∼100% efficiency, determined with 1H NMR. For encapsulation, a 10 wt% macromer solution in PBS containing 0.05 wt% 2-methyl-1-[4-(hydroxyethoxy)phenyl]-2-methyl-1-propanone (Irgacure 2959, I2959) was prepared. For polymerization, GDNF was suspended in the polymer solution at the desired concentration (250μg/ml for determination of release profile, 5μg/ml). The solution (20μl) was pipetted into a cylindrical mold and exposed to ultraviolet light for 5 min. using a long-wave ultraviolet lamp (F8T5BLB, Topbulb, East Chicago, IN).

To characterize the release profile, hydrogels (n=3) were ejected into eppendorf tubes containing 1ml PBS and placed in a 37°C incubator with gentle agitation. On days 1, 2, 4, 7, and 15, PBS containing released GDNF was sampled and stored at −20°C; tubes containing the hydrogels were refilled with fresh PBS, until complete gel degradation. GDNF content of each PBS sample was determined by ELISA (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN).

To establish the biological activity of the released GDNF, primary cultures of dissociated embryonic rat (E18) cortical cells were incubated with hydrogels containing GDNF. Cortical cells were plated at a density of 10,000 cells/well in neurobasal media containing Penicillin-Streptomycin (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). At 48 h, media was exchanged, and hydrogels containing 100ng of GDNF were suspended in triplicate wells. Control wells containing no hydrogels, hydrogels containing no GDNF, or 50ng of free GDNF in the media were also analyzed in triplicate. At 72 h after adding GDNF, 200X images were taken of each well at 5 randomly spaced regions (334×422μm) using an inverted light microscope. Images (n=15/group) were analyzed using ImageJ to determine total cell counts and percentage of cells with processes. At 7 days, new images were analyzed to assess cell count, number of cells containing at least one process, average number of processes per cell, average process length, and longest process length.42-44

In Vivo Hydrogel Behavioral Studies

In vivo studies were performed using male Holtzman rats (250−350g) (Harlan Sprague-Dawley, Indianapolis, IN). Rats were housed with a 12−12 hour light-dark cycle and free access to food and water. All surgical procedures were performed under isofluorane inhalation anesthesia and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. A C6/C7 hemilaminectomy and facetectomy exposed the C7 nerve roots on the right side, and a 100mN microvascular clip was applied to the dorsal root midway between the DRG and the dorsal root entry zone.8,9 After compression for 15 mins., one of the following treatments was applied directly to the injured root: (1) 20μl hydrogel containing 5μg GDNF (250μg/ml GDNF gel; n=6), (2) 20μl vehicle hydrogel containing PBS (vehicle gel; n=6), (3) 20μl bolus of PBS containing 5μg GDNF (250μg/ml GDNF bolus; n=6), or (4) no treatment (injury; n=6). Additional rats received surgery to expose the root without compression and with a 5μg GDNF hydrogel application (sham; n=6). The incision was closed with sutures and surgical staples.

Rats were evaluated for bilateral forepaw mechanical allodynia on postoperative days 1, 3, 5, and 7.8,9,45 Preoperatively, baseline measurements of paw withdrawal responses were recorded on consecutive days. A single blinded tester performed all allodynia testing. For each session, after 20 mins. of acclimation to the environment, rats were stimulated on the plantar surface of each forepaw using von Frey filaments (1.4, 2, 4g) (Stoelting, Wood Dale, IL). Each session consisted of 3 rounds of 10 stimulations, 10 mins. apart. The number of withdrawal responses was recorded for each filament after each round. Allodynia, determined by an increase in withdrawals over baseline, was averaged by group on each day.

Assessment of GDNF & GFRα-1 in the DRG

Rats were euthanized on day 7 by an overdose of sodium pentobarbital (40mg/kg) and transcardially perfused with 200ml of PBS followed by 200ml of 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS. The C7 ipsilateral and contralateral DRGs were harvested and placed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 1 h followed by 50% ethanol overnight. Tissue was dehydrated in graded ethanols and embedded in paraffin for longitudinal sectioning at 10μm. DRG sections were labeled for GDNF and the GFRα-1 receptor by immunohistochemistry using polyclonal antibodies against GDNF (1:100; Santa Cruz, CA) and GFRα-1 (1:100; Neuromics, Bloomington, MN). Horse anti-goat or goat anti-rabbit secondary antibodies (Vector, Burlingame, CA) were used at a dilution of 1:200. All antibody dilutions were previously optimized. Sections were exposed to 3,3-diaminobenzidine for color development (Vector) and cover-slipped using a non-aqueous mounting medium. Immunostained sections were imaged at 200X. Neuron populations were identified by cross sectional area; small neurons (<600μm2) in the DRG were identified as a measure of nociceptive neurons, and large neurons (>600μm2) were taken as mechano/proprioceptive. The number of small and large neurons positive for each of GDNF or GFRα-1 was reported as a percentage of all small or large neurons in each DRG.

Data & Statistical Analyses

Cell counts and process length measurements from the primary neural cell cultures were averaged across the wells for each group and analyzed by one-way ANOVA with post-hoc Bonferroni correction. Paw withdrawal frequencies were compared using a two-way ANOVA with repeated measures to determine significant effects of treatment over time, followed by a one-way ANOVA with post-hoc Bonferroni correction for pairwise comparisons between experimental and control groups on each day. Differences in small and large GDNF- or GFRα-1-positive neurons among groups were compared by one-way ANOVA with post-hoc Bonferroni correction. Statistical analyses were performed using SYSTAT v10.2 (SYSTAT, Richmond, CA) with data presented as mean ± std. dev. and significance at p<0.05.

Results

GDNF Release Profile & Bioassay

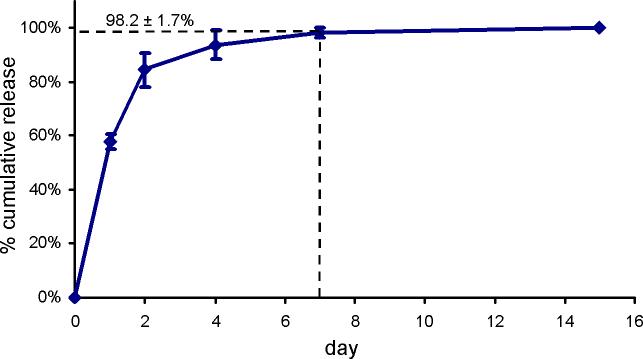

Over 15 days, degradation of the lactic acid units in the PLA-b-PEG-b-PLA macromer allowed the encapsulated GDNF to be released from the hydrogel, at which time the hydrogels were fully degraded (Fig. 1). The hydrolytic nature of degradation allowed for an assessment GDNF release in a cell- and degradative enzyme-free system, thereby eliminating cell binding or enzymatic degradation as possible sources of measurement error. After 24 h, 57.8±3.0% of the GDNF was released. Hydrogels were nearly completely degraded within 7 days, releasing 98.2±1.7% of the GDNF (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

In vitro characterization of the cumulative GDNF release from degradable PEG hydrogels. Cumulative release is expressed as a percent of total GDNF released ± std. dev.

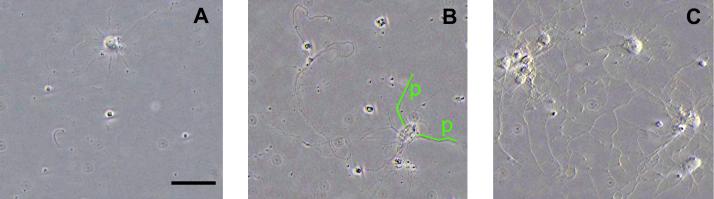

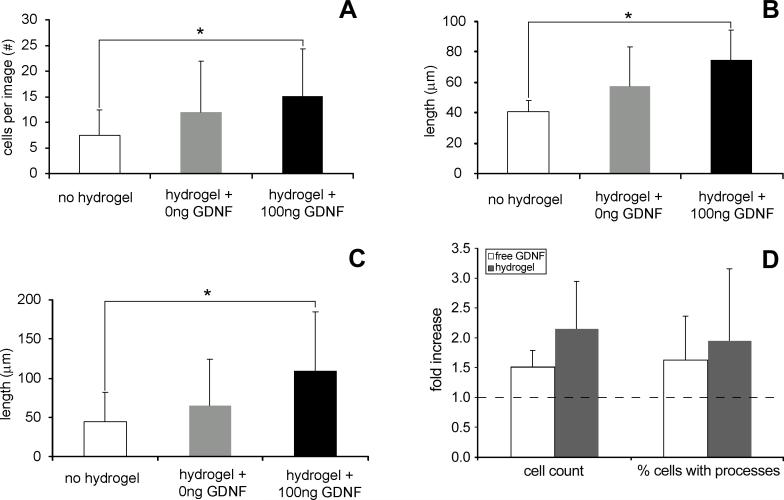

Addition of hydrogel-encapsulated GDNF to primary cortical cell cultures increased the cell count and outgrowth of processes at day 7 (Figs. 2 & 3A-C). Also, after 72 h, free GDNF and GDNF released from the hydrogel similarly increased the cell numbers and percentage of cells with processes over wells incubated without GDNF, indicating no significant loss of bioactivity from hydrogel polymerization (Fig. 3D). The number of viable neural cells, average process lengths, and lengths of the longest process were all significantly increased (p<0.043) in cultures incubated with a GDNF hydrogel compared to those with no hydrogel (Fig. 3A-C). No significant increases occurred for wells containing gels with no GDNF (Fig. 3). Cultures incubated with the GDNF hydrogel averaged 15.1±9.2 cortical cells per image (Fig. 3A), with 40.8% containing at least one process. Average process length was 74.8±19.6μm (Fig. 3B), the longest being 106.5±74.4μm (Fig. 3C). Cultures incubated without a hydrogel had 7.5±5.0 cells, with only 25.8% containing at least one process. Processes averaged 40.8±7.6μm, the longest being 43.4±37.2μm. No significant differences were observed in the number of cells containing processes or the average number of processes per cell among any of the groups.

Figure 2.

Representative images of cortical neural cells after 7 days of incubation with (A) no hydrogel, (B) a hydrogel containing no GDNF, and (C) a hydrogel containing 100ng of GDNF. Cell count and length of processes for cultures incubated in the presence of a hydrogel containing 100ng of GDNF were significantly increased (p<0.043) over cultures without a hydrogel. (B) Representative length measurements by line segments for two processes (p) are depicted. In the event of process branching, the length of the longest branch of that process was recorded. Original magnification=200X. Scale bar in (A)=50μm applies to all.

Figure 3.

(A-C) Cell counts and length of processes (+ std. dev.) at day 7 for primary rat cortical cells cultured with no hydrogel, a hydrogel with no GDNF, and a hydrogel containing 100ng of GDNF. (A) Cells per image (within a 0.08mm2 area), (B) average process length, and (C) length of the longest process all significantly (* p<0.05) increased after 7 days of incubation with a GDNF hydrogel. (D) Fold increase in cell numbers and the percentage of cells with processes at 72 h for primary cells cultured with either 50ng of free GDNF in the media or a 100ng GDNF hydrogel, normalized to cells cultured with no GDNF (dashed line). At this time about 89ng of GDNF had been released from the hydrogel. Hydrogel polymerization did not reduce the bioactivity of GDNF at 72 h based upon cell counts or process formation.

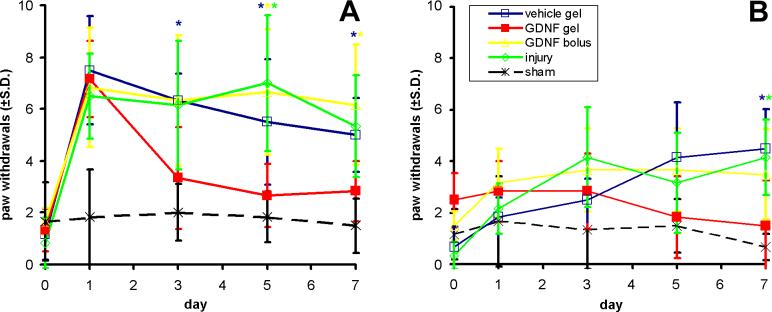

Behavioral Studies

Hydrogel-encapsulated GDNF treatment to the compressed root significantly reduced mechanical allodynia (Fig. 4). Qualitative trends in allodynia were similar and most robust for the 4g filament; as such, responses to the 4g filament are reported. For all groups receiving an injury except the GDNF gel group, allodynia in the ipsilateral forepaw was significantly greater than sham for 7 days (p<0.05; Fig. 4A). Allodynia in the GDNF gel group was evident on day 1, but did not remain elevated above sham and significantly decreased relative to both injury and vehicle gel by day 5 (p<0.03). Allodynia for the GDNF gel group was also significantly reduced relative to the GDNF bolus group by days 5 and 7 (p<0.03; Fig. 4A).

Figure 4.

(A) Ipsilateral and (B) contralateral mechanical allodynia (± std. dev.), reported as number of paw withdrawals. (A) All groups were significantly greater than sham on day 1. Only the GDNF gel group was reduced after day 1. (B) All injury control groups had significantly greater contralateral allodynia than sham at day 7. A significant increase relative to the GDNF gel group is indicated by (*).

Contralateral mechanical allodynia was produced by day 7 for all groups except the GDNF gel group (Fig. 4B). Contralateral allodynia in this latter group was significantly reduced relative to both the injury and vehicle gel groups (p<0.045). GDNF treatment with the sham procedures did not alter ipsilateral or contralateral allodynia from baseline at any time point.

GDNF & GFRα-1 in the DRG

Root compression did not significantly affect the number or size distribution of DRG neurons. GDNF-immunoreactivity in ipsilateral DRG neurons was not significantly affected for any treatment group at day 7. Sham rats exhibited GDNF-immunoreactivity in 9.2±3.3% of the small and 25.9±4.1% of the large neurons, which were not significantly different than GDNF-immunoreactivity in normal rats (Table 1). Four tissue samples from the injury group were unusable for analysis; accordingly, additional matched samples were generated by the same injury procedure (n=4 rats) to provide a complete data set. Those rats exhibited similar mechanical allodynia (data not shown) to those in the injury group. Vehicle gel and injury rats displayed GDNF-immunoreactivity in 5.1±1.0% and 5.8±1.8% of the small neurons and 20.6±5.5% and 13.8±6.7% of large neurons, respectively, a moderate decrease relative to sham, GDNF gel, and GDNF bolus (Table 1). No differences in GDNF were detected in the contralateral DRG among any groups.

Table 1.

GDNF Immunoreactivity in the Ipsilateral DRG

| Small Neurons (% GDNF-Positive) | Large Neurons (% GDNF-Positive) | |

|---|---|---|

| Normal | 8.0±3.4 | 33.2±9.7 |

| Sham | 9.2±3.3 | 25.9±4.1 |

| GDNF Gel | 12.4±7.5 | 29.3±15.2 |

| GDNF Bolus | 10.3±3.9 | 27.6±8.7 |

| Vehicle Gel | 5.1±1.0 | 20.6±5.5 |

| Injury | 5.8±1.8 | 13.8±6.7 |

Mean ± std. dev.

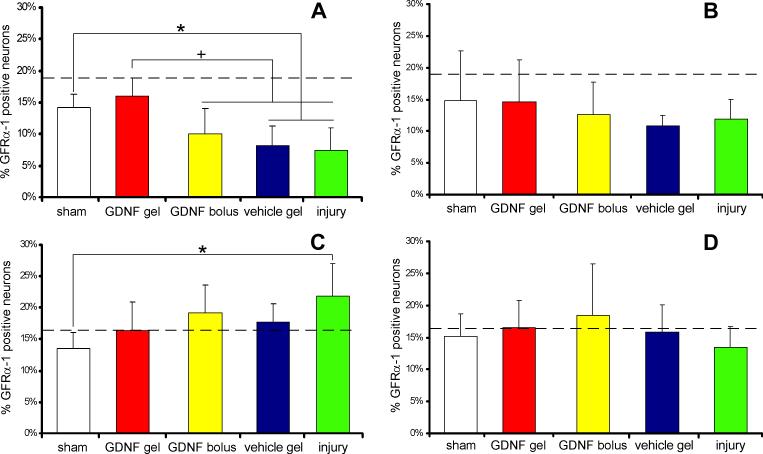

GFRα-1-immunoreactivity decreased significantly in small DRG neurons in the absence of a GDNF hydrogel (Fig. 5A). In small neurons of the ipsilateral DRG, GFRα-1-immunoreactivity was not significantly decreased for the GDNF gel group relative to sham. Yet, for vehicle gel rats, GFRα-1-immunoreactivity in small neurons (8.14±3.2%) was significantly decreased relative to the GDNF gel group (16.0±2.8%; p<0.006). Additionally, for injury rats, GFRα-1-immunoreactivity in small neurons (7. 4±3.5%) was significantly decreased relative to the GDNF gel group (p<0.001). The GDNF bolus group (10.1±3.8%) had significantly fewer GFRα-1-positive small neurons than the GDNF gel group (p<0.05; Fig. 5A). Compression decreased GFRα-1-immunoreactivity in the contralateral DRG when untreated, but this trend was not significant (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5.

GFRα-1 immunohistochemistry in the (A,C) ipsilateral and (B,D) contralateral DRG, reported as a percent of total (A,B) small (<600mm2) or (C,D) large (>600mm2) neurons (+ std. dev.). The percent of immunopositive neurons in normal rat DRGs is indicated by the horizontal dashed line. (A) In the ipsilateral DRG, the percent of GFRα-1-positive small neurons was significantly reduced (+) for the GDNF bolus, vehicle gel, and injury groups relative to the GDNF gel group. GFRα-1-immunoreactivity small neurons of the vehicle gel and injury groups was also significantly decreased (*) relative to sham. (C) GFRα-1-immunoreactivity in large neurons significantly increased (*) for the injury group relative to sham.

GFRα-1 was moderately increased in large neurons of the ipsilateral DRG for the injury group (21.7±5.1%) compared to the GDNF gel (16.4±4.4%) group, and was significantly increased compared to sham (13.5±2.5%) (Fig. 5C). No trends in GFRα-1 were observed among groups in the contralateral DRG (Fig. 5D).

Discussion

Controlled release of GDNF from degradable PEG hydrogels following compression of the cervical dorsal root reduced behavioral hypersensitivity and prevented decreases in GFRα-1 in small neurons of the ipsilateral DRG (Figs. 4 & 5). GDNF release is controlled by degradation and diffusion mechanisms that can be altered through hydrogel design (e.g., number of lactic acid units, macromer concentration). Osmotic minipump delivery rates as high as 12μg/day did not produce toxic side effects,18,22 so the release profile was optimized to deliver about half of the encapsulated GDNF (∼3μg) within the first day, corresponding to the largest decrease in GDNF in the DRG (unpublished data) and the most robust behavioral hypersensitivity.15 Over 98% of encapsulated GDNF was released by day 7 in the in vitro assay, a time point relevant for chronic behavioral symptoms and degenerative pathology in this model.8,9,41

When treated with the 10 wt% degradable PEG hydrogel containing 5μg GDNF, the allodynia normally observed following root compression was significantly attenuated and did not differ from sham after day 1. GDNF-immunoreactivity in the DRG was not significantly decreased following dorsal root compression (Table 1). Exogenous GDNF internalization by large and small DRG neurons may have increased slightly following GDNF application by bolus injection or hydrogel, yet this trend was not significant at day 7. GDNF-immunoreactivity was expected to increase in the DRG with application of exogenous GDNF;51 however, the measured GDNF-immunoreactivitiy could not be specifically determined to be from cellular internalization or changes in endogenous expression. Also, after binding the GFRα-1 receptor, GDNF might have been metabolized and cleared from the DRG rather than becoming internalized by DRG neurons. In contrast, GFRα-1-immunoreactivity was significantly decreased in small DRG neurons and increased in large DRG neurons following injury, with no significant loss of small or large neurons. Continuous GDNF administration via the hydrogel maintained GFRα-1 expression at normal levels in the ipsilateral DRG (Fig. 5A & C). These results suggest that a decrease in GFRα-1 expression in small neurons and an increase in large neurons may facilitate aberrant neuronal behavior causing radicular pain, and that preventing these changes may decrease behavioral hypersensitivity.18 A decrease in GFRα-1 expression in small, nociceptive neurons reduces the binding of GDNF-GFRα-1 to Ret, which subsequently decreases the action of the inhibitor of apoptosis proteins.20 Therefore, aberrant neuronal firing in nociceptive neurons and increased pain sensitivity18,24 may result from decreased cell viability due to decreased GFRα-1 expression. We also identified an increase in GFRα-1 expression in large DRG neurons that was prevented by continuous GDNF delivery, a phenomenon also observed after sciatic nerve transection.28 Together, these studies suggest that continuous application of exogenous GDNF may reduce allodynia by promoting enhanced receptor expression and GDNF binding in small neurons that likely mediate nociception and by preventing increased expression in large, normally non-nociceptive neurons. Additional quantitative analyses of GFRα-1 expression would provide additional insight into the mechanism by which exogenous GDNF-mediated increases in receptor expression prevent persistent pain symptoms.

Mechanical allodynia and GFRα-1-immunoreactivity for the GDNF bolus group was significantly different from the GDNF gel group in small neurons of the ipsilateral DRG, suggesting that continuous GDNF delivery is necessary to maintain its analgesic effect.18 Given the short half-life of GDNF in vivo and rapid diffusion into adjacent tissues, hydrogel delivery allows GDNF to remain at the injury site during hydrogel degradation, whereas even high doses administered by bolus injection are quickly cleared or metabolized.46 For example, while the burst release of ∼3μg of GDNF from a hydrogel over the first day provides continuous dosing, a 5μg bolus injection provides twice the dosage within minutes. Furthermore, bolus injection poses the risk of toxic side effects such as focal cell loss, pia thickening, Schwann cell hyperplasia, and ingrowth of sympathetic fibers resulting from a high dose of local delivery.37,46,47 Repeated administration of lower doses could replicate mechanical allodynia produced by the sustained delivery of a hydrogel or minipump. While repeated injections would more clearly define temporal profiles in vivo, the hydrogel delivery provides simplified treatment with alterable release kinetics eliminating multiple treatments or implantation of minipumps.18,22,48,49 Hydrogels can be delivered with light-initiated photopolymerization or through two-component redox initiating systems, where gelation occurs in vivo after the two initiators are mixed, avoiding the need for surgical implantation.34 This is important when light cannot reach the injury site. Degradable PEG hydrogels have been used to deliver neurotrophic factors to stimulate neurite growth and restore motor function in spinal cord injury models without toxic effects,34,37-40 but this study is the first to use the controlled release of GDNF to alleviate nerve root-mediated pain.

Although allodynia was significantly reduced by GDNF, early allodynia was unaffected. Continuous GDNF delivery via osmotic minipumps reduces behavioral hypersensitivity as early as day 1.18 This disparity may be explained by differences in delivery and dosing paradigms. In our study, 5μg of GDNF was released over 7 days, with less than 3μg delivered in the first day. Boucher et al. delivered 12μg per day continuously at a rate of 0.5μg/hour.18 This 4-fold increase over the first day may have been sufficient to reduce early hypersensitivity, while the cumulative effect in our study did not reduce allodynia until the third day. Cell numbers and process formation in cells incubated in free GDNF or hydrogel-encapsulated GDNF were comparable (Fig. 3D), indicating biological activity of encapsulated GDNF over one week. However, in vitro bioactivity evaluation must be interpreted as an estimated comparison because of the continuous release of GDNF from hydrogels over time. The release profile and biological activity of GDNF determined in vitro may not match in vivo release kinetics and activity. Nonetheless, hydrogel delivery substantially reduced bilateral behavioral sensitivity (Fig. 4). The improved analgesia following hydrogel delivery compared to a bolus injection further suggests efficacy of this method. Future studies involving repeated GDNF injections at different doses may indirectly provide insight into the in vivo release kinetics of GDNF.

In summary, controlled GDNF release from degradable hydrogels following transient compression of the cervical dorsal root alleviated bilateral behavioral hypersensitivity and prevented GFRα-1 receptor depletion in the DRG. Despite no evidence of altered GDNF-immunoreactivity in the DRG 7 days following injury or treatment, increased GFRα-1 expression in large neurons and decreased GFRα-1 expression in nociceptive primary afferents may have been responsible for the pain symptoms. This shift in receptor expression may have decreased the analgesic potential of GDNF, which was reversed by administration of excess exogenous GDNF from a degradable hydrogel. Controlled GDNF release from degradable PEG hydrogels in this radiculopathy model proved effective as a simple technique to deliver trophic factors continuously and directly to the injury site. These data suggest that hydrogel delivery provides significant trophic support to damaged primary afferents and is a promising treatment modality for nerve root compression-mediated pain.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Meaney and his lab for neuron cultures and recognize funding from NIH (#AR047564), NSF, and the Sharpe and Ashton Foundations.

References

- 1.Côté P, Cassidy JD, Carroll L. The factors associated with neck pain and its related disability in the Saskatchewan population. Spine. 2000;25:1109–1117. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200005010-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Freeman MD, Croft AC, Rossignol AM, et al. A review and methodologic critique of the literature refuting whiplash syndrome. Spine. 1999;24:86–96. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199901010-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carter JW, Mirza SK, Tencer AF, Ching RP. Canal geometry changes associated with axial compressive cervical spine fracture. Spine. 2000;25:46–54. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200001010-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Torg JS, Guille JT, Jaffe S. Injuries to the cervical spine in American football players. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84:112–122. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200201000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nuckley DJ, Konodi MA, Raynak GC, et al. Neural space integrity of the lower cervical spine: effect of normal range of motion. Spine. 2002;27:587–595. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200203150-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Colburn RW, Rickman AJ, DeLeo JA. The effect of site and type of nerve injury on spinal glial activation and neuropathic pain behavior. Exp Neurol. 1999;157:289–304. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1999.7065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Winkelstein BA, Rutkowski MD, Sweitzer SM, et al. Nerve injury proximal or distal to the DRG induces similar spinal glial activation and selective cytokine expression but differential behavioral responses to pharmacologic treatment. J Comp Neurol. 2001;439:127–139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hubbard RD, Winkelstein BA. Transient cervical nerve root compression in the rat induces bilateral forepaw allodynia and spinal glial activation: mechanical factors in painful neck injuries. Spine. 2005;30:1924–1932. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000176239.72928.00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rothman SM, Kreider RA, Winkelstein BA. Spinal neuropeptide responses in persistent and transient pain following cervical nerve root injury. Spine. 2005;30:2491–2496. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000186316.38111.4b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Curatolo M, Petersen-Felix S, Arendt-Nielsen L, et al. Central hypersensitivity in chronic pain after whiplash injury. Clin J Pain. 2001;17:306–315. doi: 10.1097/00002508-200112000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kobayashi S, Yoshizawa H, Hachiya Y, et al. Vasogenic edema induced by compression injury to the spinal nerve root. Distribution of intravenously injected protein tracers and gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging. Spine. 1993;18:1410–1424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kobayashi S, Yoshizawa H. Effect of mechanical compression on the vascular permeability of the dorsal root ganglion. J Orthop Res. 2002;20:730–739. doi: 10.1016/S0736-0266(01)00170-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Watkins LR, Maier SF, Goehler LE. Immune activation: the role of pro-inflammatory cytokines in inflammation, illness responses and pathological pain states. Pain. 1995;63:289–302. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(95)00186-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Igarashi T, Yabuki S, Kikuchi S, Myers RR. Effect of acute nerve root compression on endoneurial fluid pressure and blood flow in rat dorsal root ganglia. J Orthop Res. 2005;23:420–424. doi: 10.1016/j.orthres.2004.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hubbard RD, Chen Z, Winkelstein BA. Transient cervical nerve root compression modulates pain: load thresholds for allodynia and sustained changes in spinal neuropeptide expression. J Biomech. 2008;41:677–685. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2007.09.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ma C, LaMotte RH. Multiple sites for generation of ectopic spontaneous activity in neurons of the chronically compressed dorsal root ganglion. J Neurosci. 2007;27:14059–14068. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3699-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wehling P, Cleveland SJ, Heininger K, et al. Neurophysiologic changes in lumbar nerve root inflammation in the rat after treatment with cytokine inhibitors. Evidence for a role of interleukin-1. Spine. 1996;21:931–935. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199604150-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boucher TJ, Okuse K, Bennett DL, et al. Potent analgesic effects of GDNF in neuropathic pain states. Science. 2000;290:124–127. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5489.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boucher T, McMahon S. Neurotrophic factors & neuropathic pain. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2001;1:66–72. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4892(01)00010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Airaksinen MS, Saarma M. The GDNF family: signalling, biological functions and therapeutic value. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002;3:383–394. doi: 10.1038/nrn812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ma W, Eisenach JC. Morphological and pharmacological evidence for the role of peripheral prostaglandins in the pathogenesis of neuropathic pain. Eur J Neurosci. 2002;15:1037–1047. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2002.01940.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang R, Guo W, Ossipov MH, et al. Glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor normalizes neurochemical changes in injured dorsal root ganglion neurons and prevents the expression of experimental neuropathic pain. Neuroscience. 2003;121:815–824. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(03)00491-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jang J, Nam T, Paik K, Leem J. Involvement of peripherally released substance P and calcitonin gene-related peptide in mediating mechanical hyperalgesia in a traumatic neuropathy model of the rat. Neurosci Lett. 2004;360:129–132. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.02.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bennett DL, Michael GJ, Ramachandran N, et al. A distinct subgroup of small DRG cells express GDNF receptor components and GDNF is protective for these neurons after nerve injury. J Neurosci. 1998;18:3059–3072. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-08-03059.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nakamura S, Myers RR. Myelinated afferents sprout into lamina II of L3-5 dorsal horn following chronic constriction nerve injury in rats. Brain Res. 1999;818:285–290. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)01291-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Malcangio M, Getting SJ, Grist J, et al. A novel control mechanism based on GDNF modulation of somatostatin release from sensory neurones. FASEB J. 2002;16:730–732. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0971fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.ten Bokum AM, Hofland LJ, van Hagen PM. Somatostatin and somatostatin receptors in the immune system: a review. Eur Cytokine Netw. 2000;11:161–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bennett DL, Boucher TJ, Armanini MP, et al. The glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor family receptor components are differentially regulated within sensory neurons after nerve injury. J Neurosci. 2000;20:427–437. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-01-00427.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lu P, Yang H, Jones LL, et al. Combinatorial therapy with neurotrophins and cAMP promotes axonal regeneration beyond sites of spinal cord injury. J Neurosci. 2004;24:6402–6409. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1492-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhou L, Baumgartner BJ, Hill-Felberg SJ, et al. Neurotrophin-3 expressed in situ induces axonal plasticity in the adult injured spinal cord. J Neurosci. 2003;23:1424–1431. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-04-01424.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Anseth KS, Metters AT, Bryant SJ, et al. In situ forming degradable networks and their application in thissue engineering and drug delivery. J Controlled Release. 2002;78:199–209. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(01)00500-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goraltchouk A, Scanga V, Morshead CM, Shoichet MS. Incorporation of protein-eluting micospheres into biodegradable nerve guidance channels for controlled release. J Controlled Release. 2006;110:400–407. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2005.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nomura H, Katayama Y, Shoichet MS, Tator CH. Complete spinal cord transection treated by implantation of a reinforced synthetic hydrogel channel results in syringomyelia and caudal migration of the rostral stump. Neurosurg. 2006;59:183–192. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000219859.35349.EF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Piantino J, Burdick JA, Goldberg D, et al. An injectable, biodegradable hydrogel for trophic factor delivery enhances axonal rewiring and improves performance after spinal cord injury. Exp Neurol. 2006;201:359–367. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2006.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sawhney A, Pathak C, Hubbell J. Bioerodible hydrogels based on photopolymerized poly(ethylene glycol)-co-poly(alpha-hydroxy acid) diacrylate macromers. Macromolecules. 1993;26:581–7. [Google Scholar]

- 36.West JL, Hubbell JA. Photopolymerized hydrogel materials for drug-delivery applications. Reactive Polymers. 1995;25:139–147. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Burdick JA, Ward M, Liang E, et al. Stimulation of neurite outgrowth by neurotrophins delivered from degradable hydrogels. Biomaterials. 2006;27:452–459. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.06.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee AC, Yu VM, Lowe JB, et al. Controlled release of nerve growth factor enhances sciatic nerve regeneration. Exp Neurol. 2003;184:295–303. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4886(03)00258-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Taylor S, McDonald J, Sakiyama-Elbert S. Controlled release of neurotrophin-3 from fibrin gels for spinal cord injury. J Control Release. 2004;98:281–294. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2004.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Taylor S, Rosenzweig E, McDonald J, Sakiyama-Elbert S. Delivery of neurotrophin-3 from fibrin enhances neuronal fiber sprouting after spinal cord injury. J Control Release. 2006;113:226–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2006.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hubbard RD, Winkelstein BA. Nerve Root Compression Produces Axonal Degeneration Dependent on Biomechanical Thresholds for Mechanical Allodynia. Exp Neurol. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2008.04.042. in revision. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pong K, Xu RY, Beck KD, et al. Inhibition of glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor induced intracellular activity by K-252b on dopaminergic neurons. J Neurochem. 1997;69:986–994. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.69030986.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pozas E, Ibanez CF. GDNF and GFRalpha1 promote differentiation and tangential migration of cortical GABAergic neurons. Neuron. 2005;45:701–713. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.01.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Park S, Hong YW. Transcriptional regulation of artemin is related to neurite outgrowth and actin polymerization in mature DRG neurons. Neurosci Lett. 2006;404:61–66. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2006.05.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ramer MS, Priestley JV, McMahon SB. Functional regeneration of sensory axons into the adult spinal cord. Nature. 2000;403:312–316. doi: 10.1038/35002084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.O'Malley BW, Jr, Ledley FD. Somatic gene therapy. Methods for the present and future. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1993;119:1100–1107. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1993.01880220044007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Boyd RB, Hovland DN. Gordon Res Conf Barriers of the CNS. Tilton; NH: 2004. Intraputamenal infusion of r-metHUGDNF for the treatment of Parkinson's disease. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xu XM, Guenard V, Kleitman N, et al. A combination of BDNF and NT-3 promotes supraspinal axonal regeneration into Schwann cell grafts in adult rat thoracic spinal cord. Exp Neurol. 1995;134:261–272. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1995.1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Averill S, Michael GJ, Shortland PJ, et al. NGF and GDNF ameliorate the increase in ATF3 expression which occurs in dorsal root ganglion cells in response to peripheral nerve injury. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;19:1437–1445. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03241.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Takahashi N, Nagano M, Suzuki H, Umino M. Expression changes of glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor in a rat model of neuropathic pain. J Med Dent Sci. 2003;50:87–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sajadi A, Bensadoun JC, Schneider BL, et al. Transient striatal delivery of GDNF via encapsulated cells leads to sustained behavioral improvement in a bilateral model of Parkinson disease. Neurobiol Dis. 2006;22:119–129. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2005.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]