Abstract

Cesarean delivery rates continue to increase, and surgery is associated with chronic pain, often co-existing with depression. Also, acute pain in the days after surgery is a strong predictor of chronic pain. Here we tested if mode of delivery or acute pain played a role in persistent pain and depression after childbirth. In this multicenter, prospective, longitudinal cohort study, 1288 women hospitalized for cesarean or vaginal delivery were enrolled. Data were obtained from patient interviews and medical record review within 36 hours postpartum, then via telephone interviews 8 weeks later to assess persistent pain and postpartum depressive symptoms. The impact of delivery mode on acute postpartum pain, persistent pain and depressive symptoms and their interrelationships were assessed using regression analysis with propensity adjustment. The prevalence of severe acute pain within 36 hours postpartum was 10.9%, while persistent pain and depression at 8 weeks postpartum were 9.8% and 11.2%, respectively. Severity of acute postpartum pain, but not mode of delivery, was independently related to the risk of persistent postpartum pain and depression. Women with severe acute postpartum pain had a 2.5-fold increased risk of persistent pain and a 3.0-fold increased risk of postpartum depression compared to those with mild postpartum pain. In summary, cesarean delivery does not increase the risk of persistent pain and postpartum depression. In contrast, the severity of the acute pain response to childbirth predicts persistent morbidity, suggesting the need to more carefully address pain treatment in the days following childbirth.

Introduction

The cesarean delivery (CD) rate has risen over 10-fold in the last 70 years, and now approaches 39% [15]. The long term consequences of this increased exposure to surgery in young women have not been thoroughly explored. Tissue trauma from surgery represents a common cause of chronic pain and disability [13, 20] and women are at increased risk compared to men of developing chronic pain after surgery [17, 26], and exhibit higher chronic pain severity [9]. As such, CD could result in chronic pain. One small survey in a non-US population demonstrated an incidence of persistent daily pain 1 year after CD of 6% [16], but there are no prospective studies comparing the incidence of persistent pain between CD and vaginal delivery (VD). With over 4 million deliveries annually in the US alone, even a small prevalence of persistent pain carries important public health consequences. The primary purpose of this study was to determine whether CD increases the risk of persistent pain after childbirth.

Medical surveillance and intervention, intense during labor and delivery, are abruptly reduced or withdrawn after delivery, when there is a rapid transition to a more home-like environment in the hospital. The consequences of this abrupt withdrawal on pain treatment have not been adequately explored. Poorly controlled acute post-procedural pain may result in harmful physiologic and psychological consequences, including prolonged hospitalization, and delayed return to normal activities [25], and is associated with an increased risk of chronic pain [13, 20]. The prevalence of severe pain after surgery has not decreased in the last 2 decades [2]. Pain treatment after childbirth may be even less adequate than after surgery, due to relatively few nurses in postpartum wards and a reluctance to use non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or adequate doses of opioids due to concerns of the use of these drugs during breastfeeding. A secondary purpose of this study was to quantify acute pain following CD and VD and to determine whether severity of acute pain predicts persistent pain.

Chronic pain and depression commonly co-exist, and postpartum depression, a complication affecting 8-15% of postpartum women [6], affects both maternal and neonatal health [24]. CD, whether elective or emergent, most likely does not increase the risk of postpartum depression over VD [19]. In contrast, in one small study, the presence of persistent pain after childbirth increased the risk of postpartum depression 3-fold [11]. Since acute pain predicts persistent pain after surgery, a final purpose of this study was to determine the risk imparted by severity of acute pain after childbirth to the development of postpartum depression. The results of this study demonstrate that pain in the hours after childbirth imparts an important risk for persistent pain and depression and provides a new target to reduce such morbidity.

Materials and Methods

This is a prospective, longitudinal cohort study from Forsyth Medical Center, Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, NC, USA and Columbia University Medical Center, New York, NY, USA. Following Institutional Review Board approval and written informed consent, women hospitalized for CD or VD from September 2004 to December 2005 were enrolled, except during weekends and holidays when research interviewers were unavailable. Within 36 hr following delivery women were questioned using a scripted interview to assess their acute pain after delivery, pre-existing pain, pain treatment before or during pregnancy, demographic variables, degree of somatization [3], previous medical and social history, and height and weight at the end of pregnancy (Entrance Questionnaire, Appendix 1). Women were asked to quantify pain at the time of the interview and since delivery using an eleven point numerical rating pain score from 0 to 10, with 0 indicating no pain, and 10 the worst pain imaginable. Pain was considered mild if scored 0-3, moderate if scored 4-6, and severe if scored 7-10. Data were also collected regarding maternal and neonatal factors during labor and delivery (Delivery Information Questionnaire – Appendix 2).

At 8 weeks after delivery, patients were contacted and a computer-assisted, scripted telephone interview was conducted by the Research Survey Center of Wake Forest University to assess the presence of persistent postpartum pain, including intensity, frequency, location, treatment and impact on daily activities, postpartum depression (using the validated Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; [7]), and other health changes since delivery (8-week Questionnaire, Appendix 3). Persistent pain was defined as > 0 pain scores which began at or immediately after childbirth for either the average, worst or current pain during the week of the telephone interview. Postpartum depression was defined by a score of >12 on the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale [7, 21]. The primary outcome variables were acute pain after delivery and presence of persistent pain and depressive symptoms 8 weeks after delivery.

Statistical Methods

Patient recruitment was based on the goal of identifying stable estimates of pain prevalence at 8 weeks postpartum. Previous estimates of 6-12 weeks postpartum pain revealed pain prevalence ranging from 8-23%, so a sample size of N=1000 would provide confidence in the estimate of < ± 1.9%. To measure the impact of delivery mode on the primary outcome measures, we used propensity score adjustment in which we defined and controlled for 16 measured patient variables that were considered a priori to contribute to the probability that an individual would have a CD (Table 1). The use of propensity score adjustment was intended to better isolate the impact of delivery mode on outcome while simultaneously controlling for many of the other independent influences that are associated with delivery mode. Propensity scores were developed using a nonparsimonious logistic model with all 16 designated predictors (plus site) entered simultaneously. The discriminative power of the propensity scores was quantified using the area under the receiver-operating-characteristic curve (C-index). Prior to the primary analysis, a missing values analysis was performed and missing values of continuous (scale) variables were singularly imputed using the EM algorithm. The results of the primary analyses were compared with the missing data imputed versus left missing and were similar, so only the imputed results are presented.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Vaginal and Cesarean Delivery Patients.

| Vaginal Delivery (VD) (N = 837) |

Cesarean Delivery (CD) (N = 391) |

P value adjustment |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scale Variable | Mean (SD) | Missing % | Mean (SD) | Missing % | before | after |

| Age (Years) | 28.7 (6.3) |

0.2 |

30.5 (6.3) |

1.0 |

<.001 | 0.98 |

| BMI (kg/m2 ) | 31.0 (6.5) |

11.0 |

33.0 (7.3) |

15.1 |

<.001 | 0.98 |

| Gestational Age (weeks) | 38.6 (2.0) |

1.0 |

37.8 (3.4) |

2.3 |

<.001 | 0.98 |

| Sum neonate weight (kg) | 3.3 (0.6) |

2.0 |

3.4 (0.9) |

3.3 |

0.25 | 0.99 |

| Somatization (10 - 50) | 28.1 (6.1) |

0.4 |

28.7 (6.3) |

0.0 |

0.14 | 0.99 |

| Menstrual Pain (1 - 4) | 1.9 (1.1) |

0.1 |

2.0 (1.2) |

0.0 |

0.21 | 0.99 |

| Categorical Variable | n (%) | Missing % | n (%) | Missing % | before | after |

| Number of Fetuses 1 ≥ 2 |

825 (98.9) 9 (1.1%) |

0.4 |

353 (91.0) 35 (9.0) |

0.8 |

<.001 | .89 |

| Previous Cesarean Section 0 1 ≥ 2 |

809 (96.9) 24 (2.9) 2 (0.2) |

0.4 |

256 (66.5) 100 (26.0) 29 (7.5) |

1.0 |

<.001 | .88 |

| ICU admission – any newborn | 82 (9.8) |

0.2 |

93 (24.0) |

0.8 |

<.001 | .93 |

| Breech birth | 0 (0.0) |

0.0 |

67 (17.1) |

0.0 |

* | * |

| Regular doctor visits or regular medication use for other medical conditions before pregnancy- yes |

308 (37.2) |

1.1 |

143 (37.0) |

1.3 |

.98 | .99 |

| Chronic pain prior to pregnancy | 83 (10.0) |

0.5 |

43 (11.1) |

0.5 |

.41 | .99 |

| Cigarettes Use > 1 pack/week | 195 (23.3) |

0.1 |

94 (24.1) |

0.3 |

.87 | .99 |

| Alcohol Use None 1-7 drinks/week ≥ 7 drinks/week |

623 (74.6) 195 (23.4) 17 (2.0) |

0.2 |

276 (70.8) 108 (27.7) 6 (1.5) |

0.3 |

.24 | .42 |

| Previous abdominal surgery | 114 (13.7) |

0.0 |

167 (43.6) |

0.0 |

<.001 | .72 |

| Pain during pregnancy None Mild Moderate Severe |

599 (72.0) 69 (8.3) 102 (12.3) 62 (7.5) |

0.6 |

263 (67.6) 53 (13.6) 47 (12.1) 26 (6.7) |

0.5 |

.62 | .99 |

Valid estimates cannot be calculated because of non-overlap between the groups.

The primary outcomes were then analyzed using the generalized linear model. For all outcomes the effect of delivery mode was hierarchically entered into the model with the propensity score. Eight week outcomes (presence of pain and depression score) were also predicted using hierarchically entered acute post delivery pain. Because the depression scores were highly skewed, a log-normal model was specified. The presence of pain at 8 weeks was modeled using the binomial distribution with a logit link function, and acute pain was modeled using the normal distribution. All analyses were performed using SPSS 13.0 statistical software; a p value of less than 0.05 (two-tailed) was considered to indicate statistical significance. No adjustments were made for multiple comparisons.

Results

Patient Characteristics and Missing Data

From September 2004 to December 2005, 1228 patients (837 VD and 391 CD) were enrolled, with 878 patients from North Carolina and 350 patients from New York (Figure 1). To examine the potential influence of missing 8-week data on the estimates, a logistic regression model was conducted using the same predictor set as for the propensity score model (Table 1), with the addition of acute pain score at delivery. Parturients from New York (28.9% vs. 20.6%, p < 0.001) were more likely to be lost to follow-up, and so too were younger parturients, with each decade of life being associated with a 47% (p < 0.001) decrease in the odds of being lost to follow-up. Further, regular doctor visits or regular medication use for other medical conditions before pregnancy was associated with a 35% (p = 0.043) decreased chance of being lost to follow-up. Notably, experiencing previous chronic pain (p = 0.90), and severity of acute pain after delivery (p = 0.81) were not meaningfully related to the odds of being lost to follow-up.

Figure 1.

Patient Flow Chart

Table 1 presents the characteristics common to both CD and VD patients that were used in the development of the propensity score model. A total of 96.7% of patients (N=1188) were available for propensity score analysis due to 3.3% of incomplete or missing categorical data, and 939 patients were available for final 8 week assessment analysis. Compared to VD, women with CD were older, heavier, had shorter terms of gestation, were more likely to give birth to more than one fetus, had a previous CD, had a breech presentation, and were more likely to have had one of their fetuses being admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit. Characteristics unique to each delivery type are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Acute Postpartum Pain Scores, Impact on Daily Activities, and Characteristics of Vaginal and Cesarean Deliveries.

| Vaginal Deliveries | Cesarean Deliveries | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pain Scores 0 - 10 | Mean (SD) | Pain Scores 0 – 10 | Mean (SD) | ||

| Average | 3.3 (2.1) | Average | 4.7 (2.0) | ||

| Worst | 4.9 (2.8) | Worst | 7.1 (2.3) | ||

| Current | 1.9 (2.0) | Current | 3.1 (2.2) | ||

| Impact on Daily Activities |

% | Impact on Daily Activities | % | ||

| Walking | 39.8 | Walking | 71.9 | ||

| Mood | 18.6 | Mood | 40.2 | ||

| Sleep | 36.4 | Sleep | 56.5 | ||

| Interactions with others | 8.0 | Interactions with others | 19.9 | ||

| Ability to Concentrate | 12.9 | Ability to Concentrate | 30.9 | ||

| Delivery Variables | % | Average Pain Score (SD) |

Delivery Variables | % | Average Pain Score (SD) |

| Spontaneous Delivery | 95.1 | 3.3 (2.1) | First Cesarean Section | 66.5 | 4.8 (2.0) |

| Reasons for Cesarean Section: | |||||

| Assisted Forceps | 4.3 | 4.3 (2.3) | Breech & Other | 18.4 | 4.4 (1.9) |

| Fetal Macrosomia | 1.5 | 5.2 (1.5) | |||

| Assisted Vacuum | 1.6 | 3.3 (2.0) | Dystocia | 26.3 | 4.9 (2.0) |

| Non reassuring fetal heart rate tracing |

16.8 | 5.3 (2.2) | |||

| Perineal Laceration | Preeclampsia | 4.4 | 4.7 (2.5) | ||

| None | 60.0 | 4.0 (2.2) | Elective Repeat | 16.2 | 4.6 (2.0) |

| First Degree | 15.5 | 3.2 (2.2) | Other Medical Indications | 32.7 | 4.7 (2.0) |

| Second Degree | 20.8 | 3.1 (1.9) | Skin Incision Type: | ||

| ≥ Third Degree | 3.7 | 4.1 (2.0) | Pfannenstiel | 98.7 | 4.6 (2.0) |

| Midline | 1.3 | 5.6 (1.7) | |||

| Uterine Incision Type: | |||||

| Low Transverse | 95.8 4.1 |

4.6 (2.0) 5.1 (1.5) |

|||

| Other | |||||

| Drain placed | 1.3 | 3.8 (2.4) | |||

| Cesarean Anesthetic Type: | |||||

| General Anesthesia | 3.1 | 3.8 (2.0) | |||

| Neuraxial Labor Analgesia |

84.7 | 3.3 (2.1) | Labor Epidural used for Cesarean | 37.7 | 4.8 (2.0) |

| No Analgesia | 8.7 | 3.1 (2.0) | Epidural placed for Cesarean | 2.1 | 5.6 (3.0) |

| Spinal or combined Spinal-epidural | 56.3 | 4.6 (2.0) | |||

Some categories are not mutually exclusive or exhaustive, resulting in proportional membership that do not add to 100%.

The propensity score model was able to adequately distinguish between delivery modes and to balance the differences in parturient characteristics. Using all variables in Table 1, the propensity model had a C-index = .84. After propensity adjustment, all patient characteristics except for breech birth were statistically equivalent (p > .24; Table 1).

Postpartum Acute Pain at 24 hours after Delivery

Distribution of acute pain scores varied among CD and VD patients (Figure 2). Sixty-six percent of patients (57% of VD, 85% of CD) reported their pain interfered with one or more of daily activities – walking, mood, sleep, relations with others or ability to concentrate (Table 2, Appendix 4A). Delivery mode was meaningfully related to acute pain after delivery. In parturients with similar propensity scores, CD was associated with a 32.5% increase in acute pain scores, B = 1.3 (.16), p < .0001. Among VD patients, forceps delivery and higher degree of perineal laceration were associated with higher acute pain scores (Table 2).

Figure 2.

Distribution of numerical rating score (NRS) of average pain for the first 24 hr after vaginal and cesarean delivery.

Persistent Pain at 8 weeks after delivery

Prevalence of pain 8 weeks after delivery was 10.0% (95% CI: 7.7, 12.3) after VD and 9.2% (95% CI: 5.5, 12.6) after CD. Among those with persistent pain, almost half reported pain affecting one or more daily activities. Furthermore, 60% of women after VD and 40% of those after CD had pain occurring daily or constantly. The most common sites of pain were surgical scar site and back after CD and back, pelvic and birth canal after VD (Appendix 4B). Eighty three women with persistent pain came from the 763 women without previous chronic pain, a 9.8% incidence. Only 8 women with persistent pain came from the 84 women with previous chronic pain, an 8.7% incidence. Thus, and interestingly, previous pain was not a risk factor for new persistent pain (χ2 analysis; P=0.73).

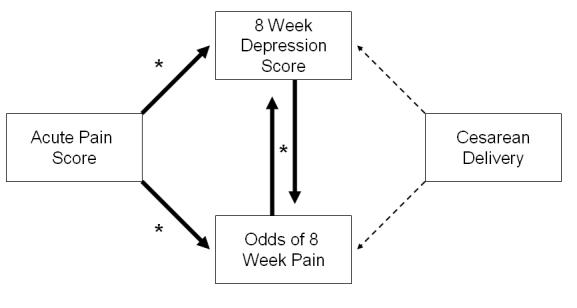

Mode of delivery was not independently related to the risk of experiencing persistent 8 week postpartum pain. This was evident both before propensity adjustment, B = −.21 (0.25), p = 0.40, and after adjustment, B = −.26 (.32), p = .34. In contrast, severity of acute pain after delivery was uniquely associated with the risk of experiencing persistent postpartum pain. In parturients with similar delivery modes and propensity scores, a one-point increase in acute pain score was associated with a 12.7% increase in the odds of experiencing pain 8 weeks later, B = 0.127 (0.05), p = .018. The presence of persistent pain had a significant bidirectional relationship with postpartum depressive symptoms, B=0.07 (0.03), p = .001. The value of acute pain in predicting the presence of 8-week pain was diminished when concurrent 8-week Edinburgh depressive symptoms were entered into the model, but a one point increase in acute pain was still able to predict a 9% yet nonsignificant, increase in the odds of having 8-week pain (B= .09 [.06], p = .09).

Postpartum depression

The overall prevalence of postpartum depression 8 weeks after delivery was 11.2% (11.4% for VD and 10.5% for CD). Mode of delivery was not independently related to the risk of experiencing postpartum depression 8 weeks after delivery. This was evident both before propensity adjustment, B = . 0.06 (0.06), p = 0.34, and after adjustment, B = 0.04 (0.08), p = 0.56. Severity of acute postpartum pain was meaningfully associated with the risk of having postpartum depression 8 weeks later. In those with similar delivery modes and propensity scores, a one-point acute pain score increase was associated with an 8.3% increase in the Edinburgh depression score, B = 0.8 (0.01), p = .0001. This relationship was maintained even after accounting for the significant bidirectional relationship between postpartum depression and persistent pain, B = 0.29 (0.07), p = .0001.

The significant interrelationships among delivery mode, acute postpartum pain, persistent pain and postpartum depression 8 weeks after delivery are modeled in Figure 3. This indicates the central and common role of acute postpartum pain rather than mode of delivery in the association with persistent pain and postpartum depression.

Figure 3. Interrelationships among delivery variables (mode of delivery and acute postpartum pain) and the 8 week outcomes (persistent pain and depression scores).

After controlling for propensity to deliver via a Cesarean delivery (not depicted), every point increase in acute pain after delivery was associated with an 8.3% increase in 8-week depressive symptoms and a 12.7% increase in the odds of experiencing pain at 8 weeks. The two 8-week outcomes were highly correlated (p < 0.0001). Giving birth via cesarean delivery was not associated with either outcome (p > 0.34).

Discussion

Childbirth is a natural process, but can result in long term maternal morbidity. Additionally, CD represents major surgery and surgical trauma. The current study suggests that pain during the immediate period after delivery, a time typically of relaxed attention to patient care, is an important contributor to significant persistent pain and depression after childbirth. Our data suggest that these morbidities are not primarily related to the degree of physical trauma, as grossly measured by cesarean compared to vaginal delivery, but rather are related to the individual's pain response to that injury. Although some variables associated with persistent pain after surgery, including anxiety, were not assessed in this study and included in the propensity analysis, the large sample size suggests that mode of delivery is extremely unlikely to represent an important risk factor for this outcome. This hypothesis is consistent not only with the current study, but with an emerging literature on inter-individual differences in pain following surgical trauma [13]. Several important implications follow from these observations.

We focused our evaluations at 2 months after delivery, since this is the time of peak prevalence of postpartum depression [19, 23]and because pain at this time after surgery correlates with chronic pain [13]. Additionally, pain and depression 2 months after delivery represent important health outcomes and public health burdens in their own right. Early postpartum depression increases the risk of insecure infant attachment and cognitive and behavioral problems in children [24], and suicide in mothers with postpartum depression accounts for 17% of late pregnancy-related death [10]. We did not determine whether depression was present in women prior to delivery, and it is conceivable that some women classified in our sample as postpartum depression had chronic depression. Although the incidence of post-partum depression is similar to that of the female US population as a whole, it is distinguished by its onset, typically within the first 6 weeks after delivery. Prior depression carries a relative risk of approximately 2.0 for postpartum depression [22]. As such, we would anticipate that a small minority of those identified in our sample with post-partum depression had preexisting depression prior to delivery.

Of patients in the current study with persistent pain at 8 weeks postpartum, 36% after CD and 60% after VD reported constant or daily pain, with half of them having difficulty performing normal daily activities, and 33 to 50% of them having their mood and/or ability to sleep negatively affected. This persistent pain might limit these mothers' ability to cope with the multiple stresses facing women shortly after delivery. These reported impacts of pain may underestimate the problem because mothers frequently do not disclose such problems because of embarrassment or lack of appropriate descriptive language even though they would like more advice and assistance [5, 14].

Although persistent pain and depression were clearly associated, the model resulting from this study indicates independent risks for each of these morbidities from severity of acute pain (Figure 3). Studies in animals suggest that acute intervention at the time of tissue trauma reduces the likelihood that chronic pain will develop [12]. Several interventional clinical trials are underway in surgical patients to test the hypothesis that the severity of acute pain is not merely a marker of chronic pain development, but actively participates in the pathophysiology of the transition from acute to chronic pain. The current study adds women after childbirth to those who may benefit from testing this hypothesis.

Variability in tissue trauma undoubtedly contributed to the large inter-individual variability in acute postpartum pain in the current study. However, similarly large variability in post-procedural pain among patients after similar, relatively standardized procedures, such as abdominal hysterectomy [4] or elective CD [18], suggests that factors other than the degree of tissue trauma contribute importantly to this variability. Although increased anxiety and degree of somatization are associated with increased individual assessment of pain after surgery, the strongest and most consistently observed predictor is sensitivity to an experimental stimulus [13]. Intrinsic factors controlling or modulating the response to painful stimuli, including genetic factors [8] likely contribute importantly to this variability. The current study highlights the need to further develop models to predict who will have significant acute and/or persistent pain after delivery.

We observed a high prevalence of severe acute pain after childbirth confirming that many hospitalized patients continue to experience moderate to severe postoperative and postpartum pain [2, 18]. Based on this study, nearly 500,000 American women may experience severe acute pain after childbirth annually. It is arguably more important for new mothers than for patients after other procedures to receive adequate pain treatment because of the demand for their prompt return to activities, bonding with and caring for the newborn. Although few would openly argue against good pain control for new mothers, recent events have erected barriers in addition to those common to the treatment of other forms of acute post traumatic pain. Opioids and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, mainstays of treatment for moderate to severe acute pain, carry warnings against their use in breastfeeding women [1]. Additionally, considerably less attention is paid to non-pharmacologic approaches to analgesia after delivery than before. The current study argues strongly for focusing more attention on improving pain control and increasing the options for pain control after childbirth, not just during childbirth.

In conclusion, 1 of 5 women after CD and 1 of 13 after VD in US tertiary care centers suffer from severe acute pain after delivery. Severity of acute postpartum pain, but not mode of delivery, imparts a large and independent risk for persistent pain and depression, with negative effects on activities of daily living and on sleep. These observations suggest the need to direct more of our focus to better management of acute pain during the first few days following childbirth in order to prevent longer term morbidities and to improve outcomes, not only for women after CD, but also for those after VD. Research is needed to define predictive factors for severe acute post-delivery pain and investigate therapeutic interventions in this high risk sub group that would reduce persistent pain and depression during this vulnerable period of the first few months after delivery.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Paula Freedman, Research Assistant at Columbia University and Lynne Harris, RN, Research Nurse and Laurel Eisenach, BA, Research Assistant Wake Forest University, for their hard work in interviewing the patients in this study.

This work was supported in part by grant GM48085 from the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD and by a grant from the Sceptor Foundation, Winston-Salem, NC. Dr. Eisenach serves on the Board of Directors of the Sceptor Foundation, Winston-Salem, NC, and receives no compensation for this service. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare related to this work.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.FDA Public Health Advisory: Use of Codeine By Some Breastfeeding Mothers May Lead To Life-Threatening Side Effects In Nursing Babies. Accessed at http://www.fda.gov/CDER/Drug/advisory/codeine.htm on 1-15-2008.

- 2.Apfelbaum JL, Chen C, Mehta SS, Gan TJ. Postoperative pain experience: Results from a national survey suggest postoperative pain continues to be undermanaged. Anesth Analg. 2003;97:534–540. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000068822.10113.9E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barsky AJ, Wyshak G, Klerman GL. The somatosensory amplification scale and its relationship to hypochondriasis. J Psychiatr Res. 1990;24:323–334. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(90)90004-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brandsborg B, Nikolajsen L, Hansen CT, Kehlet H, Jensen TS. Risk factors for chronic pain after hysterectomy: a nationwide questionnaire and database study. Anesthesiology. 2007;106:1003–1012. doi: 10.1097/01.anes.0000265161.39932.e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown S, Lumley J. Maternal health after childbirth: results of an Australian population based survey. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1998;105:156–161. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1998.tb10045.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cooper PJ, Murray L. Postnatal depression. BMJ. 1998;316:1884–1886. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7148.1884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry. 1987;150:782–786. doi: 10.1192/bjp.150.6.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Diatchenko L, Anderson AD, Slade GD, Fillingim RB, Shabalina SA, Higgins TJ, Sama S, Belfer I, Goldman D, Max MB, Weir BS, Maixner W. Three major haplotypes of the beta(2) adrenergic receptor define psychological profile, blood pressure, and the risk for development of a common musculoskeletal pain disorder. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2006;141B:449–462. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fillingim RB, Doleys DM, Edwards RR, Lowery D. Clinical characteristics of chronic back pain as a function of gender and oral opioid use. Spine. 2003;28:143–150. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200301150-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gissler M, eux-Tharaux C, Alexander S, Berg CJ, Bouvier-Colle MH, Harper M, Nannini A, Breart G, Buekens P. Pregnancy-related deaths in four regions of Europe and the United States in 1999-2000: characterisation of unreported deaths. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2007;133:179–185. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2006.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gutke A, Josefsson A, Oberg B. Pelvic girdle pain and lumbar pain in relation to postpartum depressive symptoms. Spine. 2007;32:1430–1436. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e318060a673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hefferan MP, O'Rielly DD, Loomis CW. Inhibition of spinal prostaglandin synthesis early after L5/L6 nerve ligation prevents the development of prostaglandin-dependent and prostaglandin-independent allodynia in the rat. Anesthesiology. 2003;99:1180–1188. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200311000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kehlet H, Jensen TS, Woolf CJ. Persistent postsurgical pain: risk factors and prevention. Lancet. 2006;367:1618–1625. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68700-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lydon-Rochelle MT, Holt VL, Martin DP. Delivery method and self-reported postpartum general health status among primiparous women. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2001;15:232–240. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3016.2001.00345.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Center for Health Statistics Births: Preliminary data for 2006. NVSR. 56(7) Accessed at http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr56/nvsr56_07.pdf on 1-16-2008.

- 16.Nikolajsen L, Sorensen HC, Jensen TS, Kehlet H. Chronic pain following Caesarean section. Acta Anaesth Scand. 2004;48:111–116. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2004.00271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ochroch EA, Gottschalk A, Augostides J, Carson KA, Kent L, Malayaman N, Kaiser LR, Aukburg SJ. Long-term pain and activity during recovery from major thoracotomy using thoracic epidural analgesia. Anesthesiology. 2002;97:1234–1244. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200211000-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pan PH, Coghill R, Houle TT, Seid MH, Lindel WM, Parker RL, Washburn SA, Harris L, Eisenach JC. Multifactorial preoperative predictors for postcesarean section pain and analgesic requirement. Anesthesiology. 2006;104:417–425. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200603000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patel RR, Murphy DJ, Peters TJ. Operative delivery and postnatal depression: a cohort study. BMJ. 2005;330:879. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38376.603426.D3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Perkins FM, Kehlet H. Chronic pain as an outcome of surgery - A review of predictive factors. Anesthesiology. 2000;93:1123–1133. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200010000-00038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schaper AM, Rooney BL, Kay NR, Silva PD. Use of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale to identify postpartum depression in a clinical setting. J Reprod Med. 1994;39:620–624. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weissman MM, Olfson M. Depression in women: implications for health care research. Science. 1995;269:799–801. doi: 10.1126/science.7638596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wisner KL, Parry BL, Piontek CM. Clinical practice. Postpartum depression. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:194–199. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp011542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wrate RM, Rooney AC, Thomas PF, Cox JL. Postnatal depression and child development. A three-year follow-up study. Br J Psychiatry. 1985;146:622–627. doi: 10.1192/bjp.146.6.622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu CL, Naqibuddin M, Rowlingson AJ, Lietman SA, Jermyn RM, Fleisher LA. The effect of pain on health-related quality of life in the immediate postoperative period. Anesth Analg. 2003;97:1078–1085. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000081722.09164.D5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yamashita K, Ohzono K, Hiroshima K. Five-year outcomes of surgical treatment for degenerative lumbar spinal stenosis: a prospective observational study of symptom severity at standard intervals after surgery. Spine. 2006;31:1484–1490. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000219940.26390.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.