Abstract

Peripheral nerve injury results in changes in action potential waveform, ion channel organization, and firing properties of primary afferent neurons. It has been suggested that these changes are the result of reduction in basal trophic support from skin targets. Subcutaneous injections of Fluro-Gold (FG) in the hind limb of the rat were used to identify cutaneous primary afferent neurons. Five days after FG injection, sciatic nerves were ligated and encapsulated in a silicon tube allowing neuroma formation. Green fluorescent protein (GFP)-expressing Schwann cells (SCs) were injected proximal to the cut end of the nerve. Thirteen to 22 days after injury and SC injection, the L4 and L5 dorsal root ganglia (DRG) were prepared for acute culture. Whole cell patch-clamp recordings in current clamp mode were obtained and action potential properties of medium-sized (34–45 μm) FG+ DRG neurons were characterized. In the neuroma group without cell transplantation, action potential duration and spike inflections were reduced as were the amplitude and duration of spike afterhyperpolarizations. These changes were not observed after transection by nerve crush where axons were allowed to regenerate to distal peripheral targets. In the transplantation group, GFP+-SCs were extensively distributed throughout the neuroma, and oriented longitudinally along axons proximal to the neuroma. Changes in action potential properties were attenuated in the GFP+-SC group. Thus the engrafted SC procedure ameliorated the changes in action potential waveform of cutaneous primary afferents associated with target disconnection and neuroma formation.

INTRODUCTION

Axotomy results in changes in excitability of cutaneous afferent dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neurons and in action potential waveform (Devor and Wall 1990; Gurtu and Smith 1988; Oyelese et al. 1997). Medium-sized DRG neurons (likely Aβ neurons) projecting to skin can show both fast noninflected (A0) and inflected (Ai) action potentials (Amir et al. 1999, 2002; Kim et al. 1998; Liu et al. 2002; Oyelese et al. 1997). Voltage-clamp studies indicate that within this neuronal population both fast TTX-sensitive (TTX-S) and slow TTX-resistant (TTX-R) sodium currents are present (Caffrey et al. 1992; Everill et al. 1998; Rizzo et al. 1994). Nerve ligation and encapsulation with neuroma formation resulted in a reduction in Ai action potentials and an increased number of A0 action potentials (Amir et al. 2002; Oyelese et al. 1995; Oyelese and Kocsis, 1996). Moreover, both sustained and transient potassium currents are reduced in this nerve injury model (Everill and Kocsis 1999). Studies on C type DRG neurons indicates an upregulation of sodium channel gene Nav1.3 (Cummins and Waxman 1997; Waxman et al. 1994) and a downregulation of two TTX-R sodium channel genes, Nav1.8 and Nav1.9 (also referred to as SNS and NaN, respectively). The upregulation of Nav1.3 has been suggested to account for the emergence of a rapidly repriming sodium current in axotomized axons (Cummins and Waxman 1997). While much less work has been carried out on injury-induced changes in sodium channel subtypes of medium to large Aδ-Aβ DRG neurons, several reports indicate that after neuroma formation there is a reduction in slow TTX-R currents with a singularly fast TTX-S current predominating (Everill et al. 2001; Oyelese et al. 1997.).

The mechanisms for these changes in sodium and potassium currents and in spike waveform are not fully understood. However, focal application of nerve growth factor (NGF) to cut sciatic nerve prevents the reduction in Ai spikes (Oyelese et al. 1997) and the reduction in potassium currents in Aβ DRG neurons. Leffler et al. (2002) demonstrated that glial line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) and NGF reverse changes in repriming of TTX-S currents after axotomy. Thus it is hypothesized that retrograde transport of trophic factors derived from target or peripheral nerve components such as Schwann cells (SCs) play an important role in stabilizing ion channel distribution and excitability of primary afferent neurons. We asked whether transplantation of SCs, which are known to produce neurotrophic factors, could stabilize action potential properties in a nerve ligation and enscapsulation lesion model.

METHODS

Sciatic nerve injury and SC transplantation

Adult Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats of both sexes (150–250 g) were used (n = 69). The surgical procedure was in concordance with the recommendations of the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) and was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Yale University. Sciatic nerve ligation and encapsulation was performed as previous described (Oyelese et al. 1995, 1997) with slight modifications for implanting SCs dissociated acutely from Green fluorescent protein (GFP)-expressing rats. Briefly, for the injury group (n = 19), the sciatic nerve on the left side was exposed in the middle thigh region of anesthetized (ketamine, 40 mg/kg; xylazine, 2.5 mg/kg ip) rats and was ligated and transected distal to the ligature; the proximal stump of sciatic nerve was inserted into a blind-ended silicone tube to prevent nerve regeneration (Fitzgerald et al. 1985; Oyelese et al. 1995, 1997). In the transplantation group (n = 21), four to six injections of a SC suspension (~30,000 cells/μl) were injected 3–5 mm proximal to the ligation for a total of 2.4–3.6 × 105 cells. In eight animals, DMEM alone was injected as a sham control group. Nerve crush lesions were achieved in nine rats by compressing the sciatic nerve for 20–30 s with a pair of fine forceps; this transects the axons but allows regeneration to peripheral targets (Oyelese and Kocsis 1996). Age-matched unoperated rats were used as controls (n = 12).

DRG neuron dissociation and culture

Two to 3 wk after surgery, the animals were killed under pentobarbital sodium anesthesia (50 mg/kg ip), the left lumber ganglia L4 and L5 were excised and dissociated acutely with the use of previously described methods (Liu et al. 2002). Briefly, L4 and L5 ganglia were excised in ice-cold sterile calcium-free Krebs’ solution, minced, incubated in HBSS containing 1 mg/ml collagenase A (Boehringer-Mannheim, Indianapolis, IN) followed by a solution that consisted of HBSS, 1 mg/ml collagenase D (Boehringer-Mannheim), 0.4 mg/ml 1:250 trypsin (Sigma), and 0.125 mg/ml DNase-1 (Sigma). The HBSS contained (in mM) 137 NaCl, 4.2 NaHCO3, 0.4 Na2HPO4, 5.4 KCl, 0.4 KH2PO4, 5.5 glucose, and 10 HEPES, pH 7.3 (NaOH). After enzyme treatment, the digested ganglia were carefully transferred to the culture medium (DMEM and F12 in a ratio of 1:1) containing 1 mg/ml bovine serum albumin (Sigma) and 1.5 mg/ml trypsin inhibitor (Sigma) and were gently triturated using a fire-polished Pasteur pipette and then distributed onto uncoated glass coverslips. Neurons were then kept in a 5% CO2-95% O2 incubator at 37°C. No antibiotic or NGF was added to the medium. The neurons were plated at low density (Fig. 1A), and recordings were obtained over the course of 8 h in culture before neurite extension occurred.

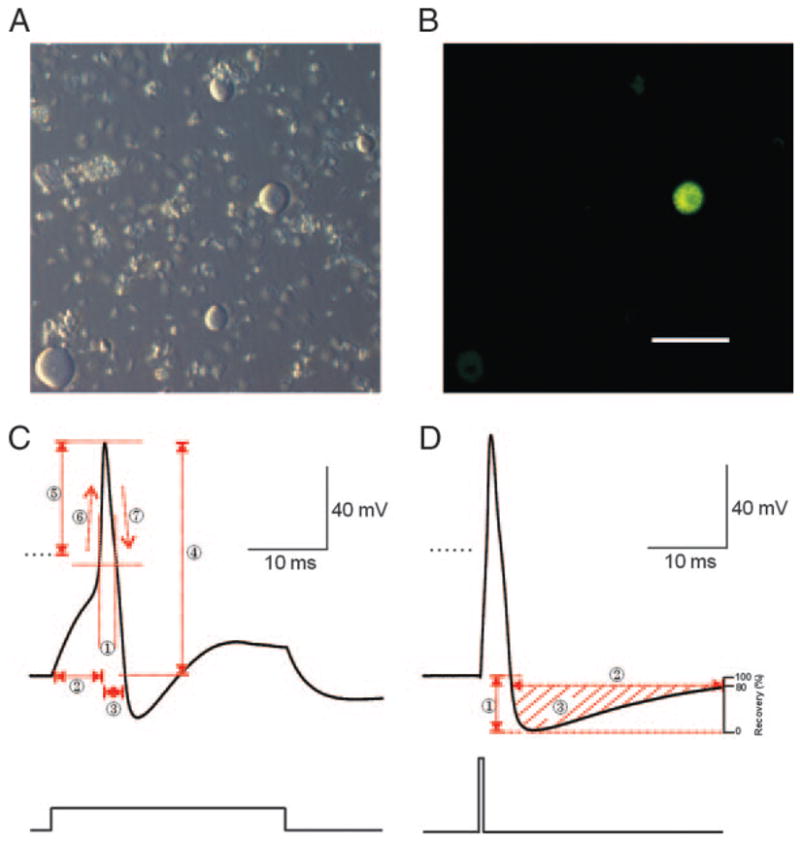

FIG. 1.

A: bright-field image (Hoffman Modulation Contrast Optics) of dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neurons isolated from L4 and L5. Note the lack of neurites. B: Fluoro-Gold retrograde labeled cutaneous afferent cell was identified by yellow fluorescence emission when exposed to ultraviolet light. C and D: parameters of action potentials (APs) recorded from medium size (34 – 45 μm) DRG neurons. Typical somatic APs of a cutaneous afferent DRG neuron evoked by either 1.2-nA, 30-ms (C) or 3.2-nA, 1-ms (D) step depolarizations. C: electrophysiological parameters measured include half-width duration (1), 90% rise time (RT) (2), 90% fall time (FT) (3), AP amplitude (4), AP overshoot (5), maximum slope of the AP rising phase (MSR) (6), and maximum slope of the AP falling phase (MSF) (7). D: AHP amplitude (1), AHP duration at 80% recovery (2) and AHP area at 80% recovery (3). Calibration bar corresponds to 100 μm.

Fluorescence tracer labeling of cutaneous and muscular afferents

Cutaneous afferent DRG neurons were identified by retrograde labeling with Fluoro-Gold (Fluorochrome, Englewood, CO) as previously described (Liu et al. 2002; Oyelese and Kocsis 1996). Five days before rats were killed, 10 –15 μl Fluoro-Gold (FG) solution (1% dissolved in sterile distilled water) was injected intradermally in the lateral region of the ankle. The labeled cells were identified in vitro in culture by yellow fluorescence emission when exposed ultraviolet light (Fig. 1B). Only neurons exhibiting a high degree of fluorescence were selected for study. Underlying muscle and tendon tissues were examined, and no FG was observed on these tissues but was confined to cutaneous tissues as previously reported (Liu et al. 2002). To eliminate errors that might arise from comparing electrophysiological properties that vary with neuronal size, an effort was made to select medium-sized cutaneous afferent neurons ranging from 34 to 45 μm for study. This neuronal size range corresponds to neurons giving rise to myelinated axon conducting in the Aβ and Aδ ranges (Harper and Lawson 1985) and was reported before to obtain waveform changes of action potential (AP) after axotomy (Olyese et al. 1995).

Preparation of donor SCs

SCs were harvested from sciatic nerves of 4- to 8-wk-old SD transgenic rats expressing GFP [“green rat” CZ-004, SD-Tg(Act-EGFP)CZ-004Osb; SLC, Shizuoka, Japan]. Sciatic nerves were desheathed, minced with a pair of scalpel blades, and incubated for 45 min in DMEM containing 10% fetal calf serum (Hyclone Laboratories, Logan, UT), 1 mg/ml Collagenase A (Boehringer-Mannheim), and 1 mg/ml Collagenase D (Boehringer-Mannheim), followed by a 15-min incubation in Ca2+-free CSS containing 0.5 mg/ml trypsin (Sigma), EDTA (Sigma), and a crystal of cysteine (Sigma). Then the nerve tissue was mechanically dissociated by trituration and washed with DMEM. The concentration of the cells suspension was counted and adjusted to about 30,000 cells/μl. Cryostat sections (12 μm) of nerve were incubated with antibodies against neurofilament (1:500; Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Sections were then washed in PBS (0.3% Triton X100 for 15 min) and incubated with appropriate secondary antibodies comprising goat anti-mouse IgG-Alexa Fluor 594 (1:1000; Molecular Probes) in blocking solution for 4 h, washed in PBS, and mounted on slides.

Electrophysiological analysis

Whole cell patch-clamp recordings were obtained 1– 8 h after plating to minimize morphological and physiological changes. Neurons plated on glass cover slips were placed in a recording chamber on the stage of an inverted microscope (Nikon) and continuously super-fused with a modified Krebs’ solution [composition (in mM) was 124 NaCl, 26 NaHCO3, 3 KCl, 1.3 NaH2PO4, 2 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, and 10 dextrose, pH 7.4 (KOH); osmolarity, 305–315 mosM at room temperature (~22°C)] bubbled continuously with 95% O2-5% CO2 at a flow rate of 0.5–1 ml/min. Only medium-sized neurons (34 – 45 μm diam) with positive FG staining were studied. Micropipettes were pulled from borosilicate glass (World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL) with a P97 micropipette puller (Sutter Instrument, San Rafael, CA) and fire polished with a microforge (Narishige, Tokyo, Japan). Electrode resistances ranged from 2 to 6 MΩ. The pipette solution contained (in mM) 140 KCl, 2 MgCl2, 1 CaCl2, 11 EGTA, 2 Mg-ATP, and 10 HEPES, pH 7.3; osmolarity, 300 –310 mosM. Recordings were included if they met all of the following criteria: >1 GΩseal resistance prior to “break-through” with further suction; a resting potential (Vr) of −55 mV or more negative; and >100 MΩ input resistance after whole cell mode was established. Once the gigaseal was established, the voltage-clamp mode was changed to current-clamp mode. The series resistance was balanced under fast current-clamp mode with an Axopatch-200B patch-clamp amplifier (Axon Instruments). The voltages were filtered at 5 kHz and acquired at 20 kHz using Clampex 8 software (Axon Instruments). The DigiData 1200B interface (Axon Instruments) was used for A-D conversion. Action potentials were elicited from Vr levels by delivering depolarizing step pulses of either 1- or 30-ms duration generated by Clampex 8.

Definitions of AP components

Parameters of somatic APs recorded from medium-sized (34 – 45 μm) cutaneous afferent DRG neurons (1.2 nA, 30-ms stimulation) were illustrated in Fig. 1C and defined as follows: AP half-width duration (ms) was measured as the width at half-maximal amplitude of APs (Fig. 1C, 1); 90% rise time (RT, ms) as 90% the duration from start of current injecting at Vr to the peak of AP (Fig. 1C, 2); 90% fall time (FT, ms) as 90% the time from peak of AP back to the baseline of Vr (Fig. 1C, 3); AP amplitude (mV) as the voltage value from the baseline at to the positive peak of the spike (Fig. 1C, 4); AP Vr overshoot (mV) as the voltage value from the baseline at 0 mV to the positive peak of the spike (Fig. 1C, 5); maximum slopes of the rising (MSR, dV/dt; Fig. 1C, 6) and falling (MSF, dV/dt; Fig. 1C, 7) phases of the AP.

Short injection of current (3.2 nA, 1 ms) were applied for measure the parameters of afterhyperpolarization (AHP) so that it will not be contaminated by injected current (Blair 2002; Liu 2002) (Fig. 1D). AHP amplitude (mV) was measured from the baseline of Vr to the negative peak of AHP (Fig. 1D, 1); AHP duration at 80% recovery (ms) was measured at the baseline at 20% AHP amplitude (Fig. 1D, 2), which is also the baseline for measuring AHP area at 80% recovery (mV*ms; Fig. 1D, 3).

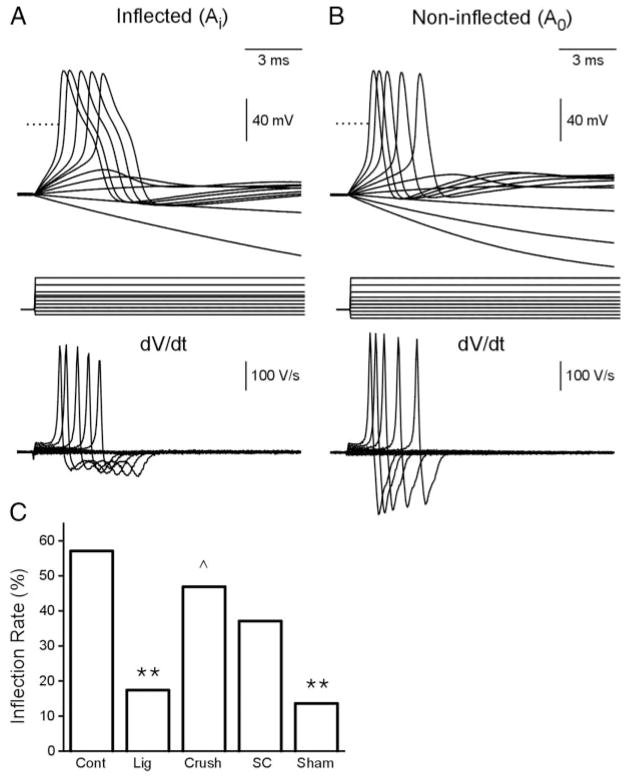

Finally, the current (nA) and voltage threshold (mV) for evoking a single spike using 30-ms depolarizing pulses, as well as the utilization time (from start of current injecting to the start of AP spiking), were measured. The neurons were further characterized as having an inflected waveform (Ai) if digital differentiation (Clampfit 8) indicated two peaks on the falling phase of the spike (Fig. 3A) or noninflected waveform (A0) if there was only one peak (Fig. 3B).

FIG. 3.

APs (top) with (A) or without (B) an inflection on the falling phase of the spike were recorded from cutaneous afferent DRG neurons evoked by 30-ms pulses ranging from −0.3 to 1.8 nA in 0.2-nA steps. Bottom: differentiated signals (digital differentiation, Clampfit 8.2). C: inflection rates (%) among the 5 experimental groups (**P < 0.01, for comparisons with normal group; ^P < 0.05, for comparisons with ligation group). Note that the number of inflected spikes is reduced in the ligation and sham group.

Statistical analysis

Electrophysiological data were processed by using Origin 6.1, Clampfit 8 (Axon Instruments) and Excel (Microsoft). Data are presented as means ± SE. Statistical evaluations were based on two-tailed t-test, χ2 test (Excel, Origin; criterion, P < 0.05).

RESULTS

Passive membrane properties of identified medium-sized cutaneous afferent DRG neurons

Whole cell current-clamp recordings were obtained from 140 dissociated medium-sized cutaneous afferent neurons. Five experimental groups were studied: control (n = 28), ligation (n = 23), nerve crush (n = 32), ligation with SC transplantation (n = 35), and sham injection (n = 22). A comparison of general membrane properties was performed to compare resting potential (Vr), input capacitance (Cap) and input resistance (Ri) among the five groups. These properties were similar for the five experimental groups (Table 1). Vr was measured in all neurons studied as soon as adequate access was attained, and it was relatively steady in the whole cell current-clamp mode. These data are presented in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

DRG membrane properties of normal, injured, and Schwann cell engrafted nerves

| Cell Membrane Properties | Control | Ligation | Nerve crush | SC Graft | Sham Graft |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Size, μm | 39.2 ± 0.4 (28) | 39.0 ± 0.4 (23) | 38.3 ± 0.5 (32) | 37.3 ± 0.4 (35) | 38.6 ± 0.4 (22) |

| Cap, pF | 58.6 ± 3.1 (28) | 60.3 ± 2.4 (23) | 59.5 ± 2.3 (32) | 64.0 ± 3.0 (35) | 67.9 ± 2.4 (22) |

| Ri, MΩ | 272.1 ± 22.3 (28) | 245.7 ± 15.5 (23) | 224.2 ± 19.5 (32) | 256.5 ± 29.4 (35) | 222.1 ± 4.7 (22) |

| Vc, mV | −67.0 ± 1.1 (28) | −65.5 ± 0.8 (23) | −63.9 ± 0.7 (32) | −64.2 ± 0.7 (35) | −64.8 ± 4.7 (22) |

Values are means ± SE with n in parentheses.

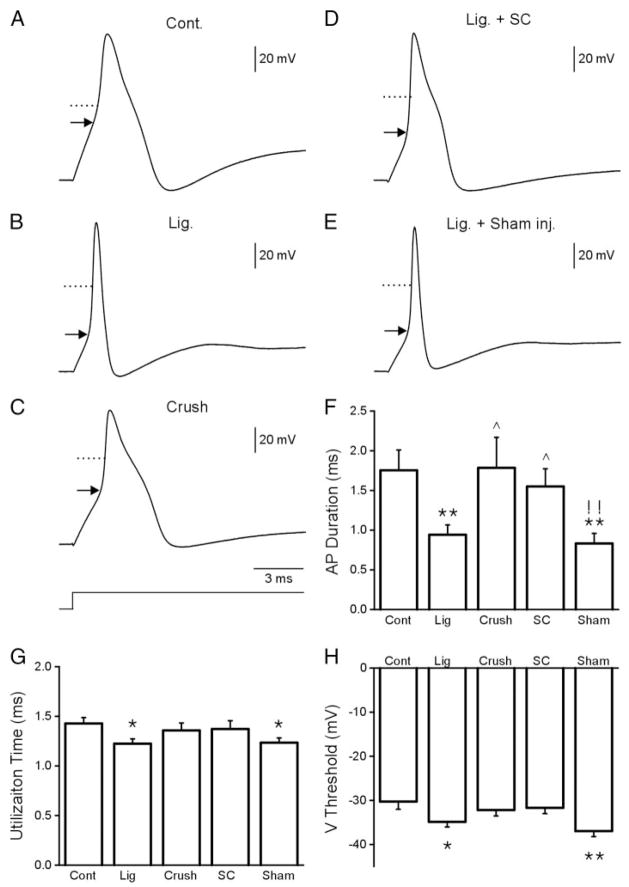

SC engraftment into the injury site prevents injury-induced changes in AP waveform

The voltage traces in Fig. 2, A–E, show APs recorded from the five experimental groups. The AP duration measured at half-maximal amplitude (AP half-width duration) was 1.75 ± 0.26 ms for the control neurons (Fig. 2, A and F; Table 2). In the ligation group the AP half-width duration was reduced to 0.94 ± 0.12 ms (Fig. 2, B and F; Table 2). In the nerve crush group where axons are completely axotomized but allowed to regenerate through the distal nerve stump, AP duration did not change (1.79 ± 0.38 ms; Fig. 2, C and F; Table 2). APs studied 2 wk after transplantation of SCs into the ligated nerve indicated that the AP narrowing observed in the ligated group did not occur in the transplant group (1.55 ± 0.22 ms; Fig. 2, D and F; Table 2). However, AP narrowing did occur in the sham group (0.83 ± 0.13 ms; Fig. 2, E and F; Table 2). The rise and fall times (RT and FT, respectively) were decreased, and the corresponding maximum slopes (MSR and MFR, respectively) increased in the ligated and sham groups but not in the SC transplant group (Table 2). Thus the AP narrowing and the increased RT and FT in the ligation group were prevented by SC transplantation into the cut and ligated nerve end.

FIG. 2.

Typical somatic action potentials recorded from cutaneous afferent DRG neurons in the control (A), nerve ligation (B), nerve crush (C), Schwann cell transplantation (D), and nerve ligation and vehicle-injection groups (E). Comparison of the AP duration, utilization time, and voltage threshold between the experimental groups are shown in F–H, respectively. (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, for comparisons with normal group; ^P < 0.05, for comparisons with ligation group; !!P < 0.01, for comparisons between Schwann cell (SC) grafting and sham group)

TABLE 2.

DRG action potential properties of normal, injured, and Schwann cell engrafted nerves

| AP Properties | Control | Ligation | Nerve Crush | SC Graft | Sham Graft |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current threshold, nA | 0.53 ± 0.05 (28) | 0.54 ± 0.04 (23) | 0.67 ± 0.05 (32) | 0.64 ± 0.04 (35) | 0.54 ± 0.06 (22) |

| Voltage threshold, mV | ±30.3 ± 1.7 (28) | ±34.9 ± 1.1 (23)* | ±32.2 ± 1.4 (32) | ±31.7 ± 1.3 (35) | ±37.0 ± 1.3 (22)** |

| UT, ms | 1.43 ± 0.06 (28) | 1.22 ± 0.05 (23)* | 1.36 ± 0.08 (32) | 1.37 ± 0.08 (35) | 1.23 ± 0.05 (22)* |

| Amplitude, mV | 113.3 ± 1.9 (28) | 112.2 ± 2.1 (23) | 109.4 ± 1.4 (32) | 111.0 ± 1.6 (35) | 111.0 ± 1.3 (22) |

| Overshot amplitude, mV | 46.6 ± 1.7 (28) | 46.2 ± 1.6 (23) | 44.1 ± 1.4 (32) | 45.8 ± 1.3 (35) | 44.6 ± 1.4 (22) |

| Half-width duration, ms | 1.75 ± 0.26 (28) | 0.94 ± 0.12 (23)** | 1.79 ± 0.38 (32)^ | 1.55 ± 0.22 (35)^ | 0.83 ± 0.13 (22)**!! |

| 90% RT, ms | 1.38 ± 0.08 (28) | 1.04 ± 0.05 (23)** | 1.18 ± 0.08 (32) | 1.23 ± 0.10 (35) | 0.99 ± 0.05 (22)**! |

| 90% FT, ms | 2.03 ± 0.31 (28) | 1.01 ± 0.14 (23)* | 2.86 ± 0.96 (32) | 1.86 ± 0.31 (35)^ | 0.88 ± 0.16 (22)*! |

| MSR, V/s | 254.1 ± 25.0 (28) | 334.3 ± 23.1 (23)* | 314.2 ± 24.2 (32) | 313.8 ± 21.8 (35) | 363.4 ± 18.9 (22)** |

| MSF, V/s | ±115.2 ± 13.4 (28) | ±167.5 ± 12.9 (23)** | ±133.3 ± 14.4 (32) | ±134.3 ± 13.4 (35) | ±194.5 ± 14.6 (22)**!! |

| Inflected, % | 57.1 (16/28) | 17.4 (4/23)** | 46.9 (15/32)^ | 37.1 (13/35) | 13.6 (3/22)** |

Values, except for percentages, are means ± SE with n in parentheses. UT, utilization time; RT and FT, rise and fall time; MSR and MSF, rise and fall maximum slope.

P < 0.05,

P < 0.01, comparisons with normal DRG neurons.

P < 0.05,

P < 0.01, comparisons with ligation group.

P < 0.05,

P < 0.01, comparisons between Schwann cell (SC) graft and sham group.

SC engraftment into the nerve injury site prevents injury-induced changes in voltage threshold and AP utilization time

AP threshold was measured by application of step depolarizations. The voltage threshold for spike initiation was −30.3 ± 1.7 mV for the control group and −34.9 ± 1.1 mV for the ligation group. Voltage threshold was also lowered in the sham group (−37.0 ± 1.3 mV) but not in the crush (−37.2 ± 1.4 mV) and SC transplant group (−31.7 ± 1.3 mV). These data are summarized in Fig. 2H and Table 2. Moreover, the utilization time (UT) for spike initiation was decreased from 1.43 ± 0.06 ms (control) to 1.22 ± 0.05 and 1.23 ± 0.05 ms in the ligated and sham groups, respectively. The SC transplant group (1.37 ± 0.08 ms) and the nerve crush group (1.36 ± 0.08 ms) did not show changes in UT (data summary in Fig. 2G and Table 2). These changes in voltage threshold, together with decreased utilization time indicate that DRG neurons of the ligated group can be more readily activated and that SC transplantation prevents these changes.

Effects of nerve injury and SC engraftment on AP inflections

The APs of the medium-sized cutaneous afferent DRG neurons were characterized as inflected (Ai) or noninflected (A0) based on the presence or absence of an inflection on the falling phase of the AP (Fig. 3A, top). The AP inflections were evident as two peaks in waveforms obtained after digital differentiation (dV/dt, clampfit 8.2; Fig. 3B, bottom). More than half of the control APs (57.1%, 16/28) displayed varying degrees of inflection on the falling phase of the AP (Fig. 3C, Table 2). In the ligation group, 17.4% (4/23) of the APs were inflected, and 46.9% inflected APs were observed in the crush group (15/32). In the SC graft group, 37.1% (13/35) of the APs were inflected as compared 13.6% (3/22) in the sham group. These data are summarized in Fig. 3C and in Table 2.

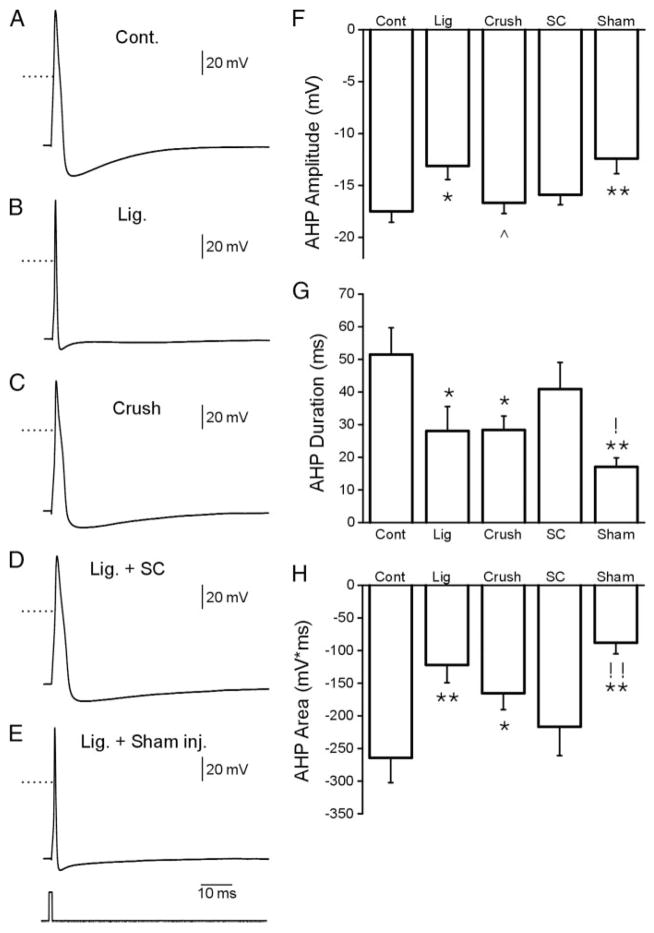

Effects of nerve injury and SC engraftment on AP AHP

Representative APs and AHPs recorded from DRG neurons for the five experimental groups are shown in Fig. 4, A–E. Comparison measurements were obtained for AHP amplitude (Fig. 4F), AHP duration (80% recovery; Fig. 4G) and the area of the AHP (Fig. 4H). AHP amplitude, duration, and area were reduced in the ligation, crush, and sham groups. These parameters of the AHP were not changed in the SC transplantation group (Fig. 4, F–H, and Table 3). Thus changes observed in the AHP after nerve ligation were reduced in the SC transplantation group.

FIG. 4.

Slow sweep action potentials with afterhy-perpolarization (AHP) recorded from the 5 experimental groups (A–E). Comparison of AHP amplitude, duration and area are shown in F–H, respectively. (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, for comparisons with normal group; ^P < 0.05, for comparisons with ligation group; !P < 0.05, !! P < 0.01, for comparisons between SCs grafting and sham group)

TABLE 3.

DRG afterhyperpolarization properties

| AHP Properties | Control | Ligation | Nerve Crush | SC Graft | Sham Graft |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amplitude, mV | −17.5 ± 1.1 (27) | −13.1 ± 1.3 (23)* | −16.7 ± 1.0 (32)^ | −15.9 ± 1.0 (33) | −12.4 ± 1.4 (22)** |

| 80% recovery duration, ms | 51.5 ± 8.2 (27) | 28.1 ± 7.5 (23)* | 28.4 ± 4.3 (32)* | 40.9 ± 8.2 (33) | 17.1 ± 2.7 (22)**! |

| 80% recovery area, mV* ms | −264.3 ± 38.0 (27) | −122.0 ± 27.3 (23)** | −165.4 ± 25.2 (32)* | −216.7 ± 44.3 (33) | −88.0 ± 16.9 (22)**!! |

Values are means < SE with n in parentheses.

P < 0.05;

P < 0.01, comparisons with normal DRG neurons.

P < 0.05,

P < 0.01, comparisons with ligation group.

P < 0.05,

P < 0.01, comparisons between SC graft and sham group.

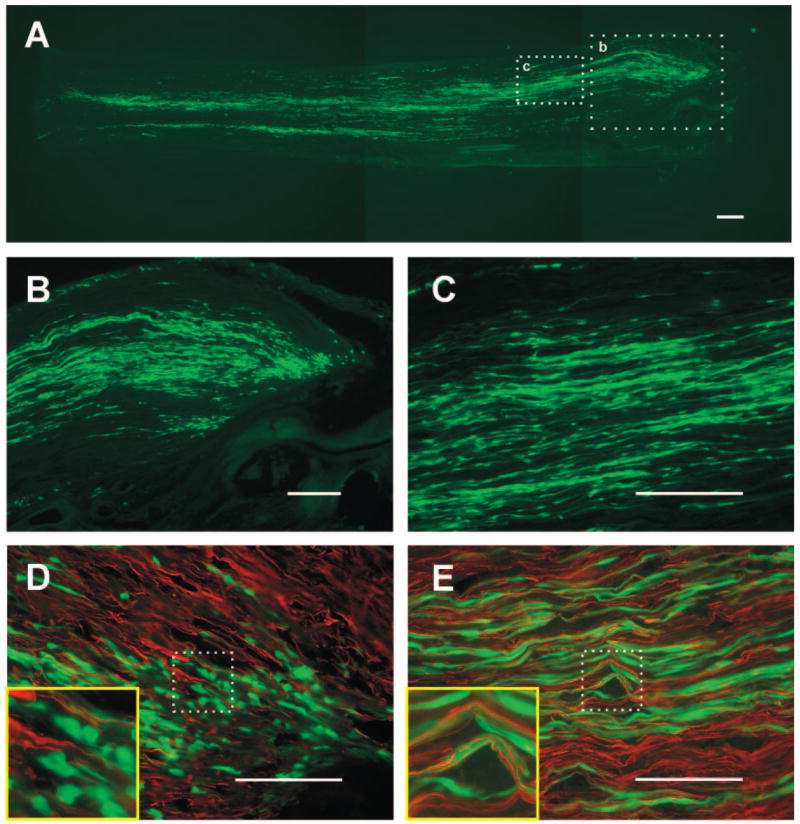

Distribution and morphology of engrafted GFP+-SCs into ligated sciatic nerve

The GFP-expressing SCs integrated into the cut nerve end and distributed longitudinally. Figure 5A is a longitudinal frozen section of the sciatic nerve and neuroma (right) 2 wk after nerve ligation and SC transplantation. GFP-expressing cell profiles can be seen in the neuroma head (Fig. 5B) and are distributed longitudinally in the proximal nerve trunk (Fig. 5, A and C). In neurofilament immunostained sections, the relationship to GFP-SCs and axons can be identified. In the neuroma head, the engrafted GFP-SCs distributed as spheroidal and fusiform cells with short thin processes that intermingled with axons but did not form prominent longitudinal association with axons (Fig. 5D). However, at more proximal regions of the nerve prominent longitudinal processes were formed by the GFP-SCs which ran in parallel to the axons (Fig. 5E).

FIG. 5.

Images of transplanted SCs from GFP+ rats in the proximal stump of axotomized sciatic nerves. A: montage showing distribution of engrafted Schwann cells (green). The neuron head is to the right. B: enlargement of boxed area b in A. The grafted SCs distributed not only in the neuroma head but also in the proximal stump of the nerve. C: enlargement of boxed area c in A. The cells distributed longitudinally and parallel with axons in proximal regions. The association of engrafted GFP-SCs to neurofilament immunostained axons in the neuroma head (D) and proximal region (E). Within the neuroma head, the cells were where spheroidal and fusiform and did not issue long processes associated with axons (D). In proximal nerve regions, the GFP-SCs distributed longitudinal processes that were intimately associated with axons. Calibration bar corresponds to 100 μm. Insets in D and E are 4 times enlargements.

DISCUSSION

After sciatic nerve section, the transected axons die back for a few millimeters over the course of the first few days after injury, and then regenerate toward distal targets or in the case of nerve ligation, toward the ligation (Ramon y Cajal 1928). Just proximal to the site of ligation a bulbous enlargement or neuroma forms. The neuroma is a complex mass containing numerous nonmyelinated axonal sprouts that grow circuitously within the neuroma. Much work indicates that the neuroma can be the site of ectopic impulse generation and a source of neuropathic pain (for reviews, see Devor 1994; Kocsis and Devor 2000). Moreover, a number of changes on the cell bodies of cutaneous afferents occur after neuroma formation including reorganization of sodium (Cummins et al. 1997; Everill et al. 2001) and potassium (Everill and Kocsis 1999) channels and GABAA receptors (Oyelese et al. 1995, Oyelese and Kocsis 1996). Changes in sodium (Dib-Hajj et al. 1998) and potassium (Everill and Kocsis 2000) channels have been reduced by focal application NGF to the cut nerve end. Although SCs are known to be a source of a variety of neurotrophic factors (Carroll et al. 1997; Curtis et al. 1994; Hall et al. 1997; Hoke et al. 2002; Lee et al. 1995; Terenghi 1999), and neurotrophin production by the engrafted cells might contribute to our observations, we have no direct data to support this view. The results of the present study indicate that transplantation of SCs ameliorated injury-induced changes in AP waveform of medium-sized cutaneous afferents. This neuronal size population likely includes Aβ and possibly Aδ neurons but clearly excludes C-type neurons.

SCs engrafted into the proximal region of a ligated sciatic nerve survive and migrate

GFP-expressing SCs transplanted into transected sciatic nerve survived within the nerve. The donor cells were observed both within the head of the neuroma near the ligature and along the proximal nerve trunk. Many cells within the head of the neuroma did not appear to be longitudinally associated with axons but rather were spheroidal or bipolar spindle-shaped cells with thin elongated processes. In contrast, many of the proximal cells were distributed longitudinally in association with axons. GFP+-SCs were observed several millimeters proximal to the neuroma head. It is likely that the donor SCs were able to compete with endogenous SCs in the proximal nerve stump to longitudinally associate with axons, and that they maintained a spheroidal phenotype within the neuroma head. Moreover, the GFP-SCs survived and integrated within the nerve without immunosuppression, indicating that cell rejection did not occur. However, we cannot rule out the possibility of an immune response by the engraftment that could possibly contribute to the observed changes in DRG APs.

Changes in DRG AP properties after nerve ligation and neuroma formation

A number of changes in spike waveform have been reported after peripheral nerve injury including spike broadening (Kim et al. 1998; Stebbing et al. 1999) and narrowing (Oyelese et al. 1995; 1997). Action potential broadening was reported in nerve injury models where axons were transected but not encapsulated to prevent outgrowth in peripheral tissues (Kim et al. 1998; Stebbing et al. 1999). We found that if the nerve was ligated and encapsulated to prevent regeneration and reinnervation of target, the APs of identified medium-sized cutaneous afferents were narrowed and the inflection on the falling phase of the AP was eliminated or reduced as studied 2 wk after injury. Indeed, previous studies indicate that at 2 wk after nerve encapsulation that a kinetically slow Na+ current is reduced and that a singular fast Na+ current predominates in medium-sized cutaneous afferents (Oyelese et al. 1997). Moreover, the AHP amplitude and duration were both reduced 2 wk after nerve ligation. It is interesting in this regard that both sustained (K+ current) and a transient K+ (A current) currents of DRG neurons are reduced to about one-half in this injury model (Everill and Kocsis 1999); this may account for the changes in AHP properties.

SCl transplantation reduces injury-induced changes in AP properties

Changes in AP waveform, sodium (Oyelese et al. 1997), and potassium currents (Everill and Kocsis 2000) of DRG neurons induced by nerve ligation and encapsulation are reduced by direct application of NGF to the nerve injury site. It was hypothesized that target-derived NGF plays a role in regulating sodium and potassium channel organization on cutaneous afferent fibers after target disconnection (Dib-Hajj et al. 1998; Everill and Kocsis 2000; Oyelese et al. 1997). SCs are known to play a critical role in modulating sodium channel isoform expression in spinal sensory neuron either in vivo (Rasband et al. 2003) or in vitro (Hinson et al. 1997). The altered sodium channel isoform organization due to the lack of normal neuron-glia contact may contribute to the pathophysiological changes in nerve injury or demyelinating diseases. Introduction of exogenous SCs into the nerve-injury site reduced AP narrowing, the reduction of the inflected APs, and changes in the AHP. One possibility to account for these observations is that the engrafted SCs provided neurotrophic support that could be transported retrogradely to the DRG cell body to substitute for the loss of skin-derived neurotrophins. It is interesting that the changes in spike waveform were reduced in the nerve crush model where the axons are completely transected but allowed to regenerate through the SC-enriched distal nerve segment and to peripheral targets. Both NGF and p75 receptor are upregulated on the SCs (Heumann et al. 1987; Taniuchi et al. 1988) of the distal segment and may provide sufficient trophic support during the regeneration process to ameliorate ion channel changes associated with changes in AP waveform. As mentioned, there are a number of potential neurotrophins besides NGF including neurotrophin-3 (NT-3), brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), glial line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF), ciliary neurotrophic factor (CNTF), leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF), and neuroegulins (Carroll et al. 1997; Curtis et al. 1994; Hall et al. 1997; Hoke et al. 2002; Lee et al. 1995; Terenghi 1999) that could contribute to this effect; we present no direct data implicating a particular neurotrophin. We hypothesize that transplantation of cultured SCs into the nerve-injury site provides an additional cellular neurotrophin source that may extend neurotrophin availability and thus limit changes in ion channel expression and changes in spike waveform. Clearly, additional biochemical studies will be necessary to directly address this hypothesis.

In the uninjured animal, cutaneous afferents associate with beta-keratinocytes in skin; beta-keratinocytes are a known source of at least one neurotrophin, NGF (Yiangou et al. 2002). The beta-keratinocyte may provide an ambient level of neurotrophin to maintain and stabilize appropriate Na+ and K+ channel organization of cutaneous afferents. In the case of neuroma formation, such an ambient source of neurotrophin may not be adequate to compensate for the lack of target-derived neurotrophic factor to maintain cell survival or normal function (Heumann et al. 1987; Johnson et al. 1985; Terenghi 1999), thus leading to altered ion channel expression and altered spike waveform (Oleyese et al. 1995, 1996). After nerve ligation, the endogenous SCs will require time to dissociate from the degenerating axon segments before they upregulate their expression of neurotrophins. The engrafted SCs may be primed by the dissociation protocol to more rapidly express neurotrophins and their receptors compared with the endogenous SCs in the proximal segment of transected nerve. The engrafted SCs may provide a transient source of neurotrophin during a critical period after nerve ligation before resident SCs are capable of doing so. The results of this study indicate that focal implantation of SCs into encapsulated blind end neuroma reduces injury-induced changes in primary cutaneous afferent AP waveform. This suggests that a cellular therapeutic approach may be considered in stabilizing AP waveform after traumatic nerve injury.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Karen Lankford for expert preparation of Schwann cells.

GRANTS

This work was supported in part by the Medical Research and the Rehabilitation Research Services of the Department of Veterans Affairs, the National Multiple Sclerosis Society, the National Institutes of Health, and the Bumpus Foundation.

References

- Amir R, Liu CN, Kocsis JD, Devor M. Oscillatory mechanism in primary sensory neurons. Brain. 2002;125:421–435. doi: 10.1093/brain/awf037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amir R, Michaelis M, Devor M. Membrane potential oscillations in dorsal root ganglion neurons: role in normal electrogenesis and neuropathic pain. J Neurosci. 1999;19:8589–8596. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-19-08589.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair NT, Bean BP. Roles of tetrodotoxin (TTX)-sensitive Na+ current, TTX-resistant Na+ current, and Ca2+ current in the action potentials of nociceptive sensory neurons. J Neurosci. 2002;22:10277–10290. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-23-10277.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caffrey JM, Eng DL, Black JA, Waxman SG, Kocsis JD. Three types of sodium channels in adult rat dorsal root ganglion neurons. Brain Res. 1992;592:283–297. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)91687-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll SL, Miller ML, Frohnert PW, Kim SS, Corbett JA. Expression of neuregulins and their putative receptors, ErbB2 and ErbB3, is induced during Wallerian degeneration. J Neurosci. 1997;17:1642–1659. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-05-01642.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummins TR, Waxman SG. Downregulation of tetrodotoxin-resistant sodium currents and upregulation of a rapidly repriming tetrodotoxin-sensitive sodium current in small spinal sensory neurons after nerve injury. J Neurosci. 1997;17:3503–35014. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-10-03503.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis R, Scherer SS, Somogyi R, Adryan KM, Ip NY, Zhu Y, Lindsay RM, DiStefano PS. Retrograde axonal transport of LIF is increased by peripheral nerve injury: correlation with increased LIF expression in distal nerve. Neuron. 1994;12:191–204. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90163-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devor M, Seltzer Z. Pathophysiology of damaged nerves in relation to chronic pain. In: Wall PD, Melzack R, editors. Testbook of Pain. 4. London: Churchill Livingston; 1999. pp. 129–164. [Google Scholar]

- Devor M, Wall PD. Cross-excitation in dorsal root ganglia of nerve-injured and intact rats. J Neurophysiol. 1990;64:1733–1746. doi: 10.1152/jn.1990.64.6.1733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dib-Hajj SD, Black JA, Cummins TR, Kenney AM, Kocsis JD, Waxman SG. Rescue of alpha-SNS sodium channel expression in small dorsal root ganglion neurons after axotomy by nerve growth factor in vivo. J Neurophysiol. 1998;79:2668–2676. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.79.5.2668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everill B, Cummins TR, Waxman SG, Kocsis JD. Sodium currents of large (Abeta-type) adult cutaneous afferent dorsal root ganglion neurons display rapid recovery from inactivation before and after axotomy. Neuroscience. 2001;106:161–169. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00258-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everill B, Kocsis JD. Reduction in potassium currents in identified cutaneous afferent dorsal root ganglion neurons after axotomy. J Neurophysiol. 1999;82:700–708. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.82.2.700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everill B, Kocsis JD. Nerve growth factor maintains potassium conductance after nerve injury in adult cutaneous afferent dorsal root ganglion neurons. Neuroscience. 2000;100:417–422. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00263-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everill B, Rizzo MA, Kocsis JD. Morphologically identified cutaneous afferent DRG neurons express three different potassium currents in varying proportions. J Neurophysiol. 1998;79:1814–1824. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.79.4.1814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald M, Wall PD, Goedert M, Emson PC. Nerve growth factor counteracts the neurophysiological and neurochemical effects of chronic sciatic nerve section. Brain Res. 1985;332:131–141. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(85)90396-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurtu S, Smith PA. Electrophysiological characteristics of hamster dorsal root ganglion cells and their response to axotomy. J Neurophysiol. 1988;59:408–423. doi: 10.1152/jn.1988.59.2.408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall SM, Li H, Kent AP. Schwann cells responding to primary demy-elination in vivo express p75NTR and c-erbB receptors: a light and electron immunohistochemical study. J Neurocytol. 1997;26:679–690. doi: 10.1023/a:1018502012347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper AA, Lawson SN. Conduction velocity is related to morphological cell type in rat dorsal root ganglion neurones. J Physiol. 1985;359:31–46. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1985.sp015573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heumann R, Korsching S, Bandtlow C, Thoenen H. Changes of nerve growth factor synthesis in nonneuronal cells in response to sciatic nerve transection. J Cell Biol. 1987;104:1623–1631. doi: 10.1083/jcb.104.6.1623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinson AW, Gu XQ, Dib-Hajj S, Black JA, Waxman SG. Schwann cells modulate sodium channel expression in spinal sensory neurons in vitro. Glia. 1997;21:339–349. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-1136(199712)21:4<339::aid-glia1>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoke A, Gordon T, Zochodne DW, Sulaiman OA. A decline in glial cell-line-derived neurotrophic factor expression is associated with impaired regeneration after long-term Schwann cell denervation. Exp Neurol. 2002;173:77–85. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2001.7826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson EM, Jr, Yip HK. Central nervous system and peripheral nerve growth factor provide trophic support critical to mature sensory neuronal survival. Nature. 1985;314:751–752. doi: 10.1038/314751a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YI, Na HS, Kim SH, Han HC, Yoon YW, Sung B, Nam HJ, Shin SL, Hong SK. Cell type-specific changes of the membrane properties of peripherally-axotomized dorsal root ganglion neurons in a rat model of neuropathic pain. Neurosci. 1998;86:301–309. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00022-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kocsis JD, Devor M. Altered excitability of large diameter cutaneous afferents following nerve injury: consequences for chronic pain. In: Devor M, Rowbotham MC, Wiesenfeld-Hallin Z, editors. Proceedings of the 9th World Congress on Pain. Progress in Pain Research and Management; Seattle: IASP Press; 2000. pp. 119–135. [Google Scholar]

- Lee DA, Zurawel RH, Windebank AJ. Ciliary neurotrophic factor expression in Schwann cells is induced by axonal contact. J Neurochem. 1995;65:564–568. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1995.65020564.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leffler A, Cummins TR, Dib-Hajj SD, Hormuzdiar WN, Black JA, Waxman SG. GDNF and NGF reverse changes in repriming of TTX-sensitive Na(+) currents following axotomy of dorsal root ganglion neurons. J Neurophysiol. 2002;88:650–658. doi: 10.1152/jn.2002.88.2.650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu CN, Devor M, Waxman SG, Kocsis JD. Subthreshold oscillations induced by spinal nerve injury in dissociated muscle and cutaneous afferents of mouse DRG. J Neurophysiol. 2002;87:2009–2017. doi: 10.1152/jn.00705.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oyelese AA, Eng DL, Richerson GB, Kocsis JD. Enhancement of GABAA receptor-mediated conductances induced by nerve injury in a subclass of sensory neurons. J Neurophysiol. 1995;74:673–683. doi: 10.1152/jn.1995.74.2.673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oyelese AA, Kocsis JD. GABAA-receptor-mediated conductance and action potential waveform in cutaneous and muscle afferent neurons of the adult rat: differential expression and response to nerve injury. J Neurophysiol. 1996;76:2383–2392. doi: 10.1152/jn.1996.76.4.2383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oyelese AA, Rizzo MA, Waxman SG, Kocsis JD. Differential effects of NGF and BDNF on axotomy-induced changes in GABA(A)-receptor-mediated conductance and sodium currents in cutaneous afferent neurons. J Neurophysiol. 1997;78:31–42. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.78.1.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramon y Cajal S. Degeneration and Regeneration of the Nervous System. Vol. 1 London: Oxford Univ. Press; 1928. [Google Scholar]

- Rasband MN, Kagawa T, Park EW, Ikenaka K, Trimmer JS. Dysregulation of axonal sodium channel isoforms after adult-onset chronic demyelination. J Neurosci Res. 2003;73:465–470. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzo MA, Kocsis JD, Waxman SG. Slow sodium conductances of dorsal root ganglion neurons: intraneuronal homogeneity and interneuronal heterogeneity. J Neurophysiol. 1994;72:2796–2815. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.72.6.2796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stebbing MJ, Eschenfelder S, Habler HJ, Acosta MC, Janig W, McLachlan EM. Changes in the action potential in sensory neurons after peripheral axotomy in vivo. Neuroreport. 1999;10:201–206. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199902050-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taniuchi M, Clark HB, Schweitzer JB, Johnson EM., Jr Expression of nerve growth factor receptors by Schwann cells of axotomized peripheral nerves: ultrastructural location, suppression by axonal contact, and binding properties. J Neurosci. 1988;8:664–681. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.08-02-00664.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terenghi G. Peripheral nerve regeneration and neurotrophic factors. J Anat. 1999;194:1–14. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-7580.1999.19410001.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waxman SG, Kocsis JD, Black JA. Type III sodium channel mRNA is expressed in embryonic but not adult spinal sensory neurons, and is re-expressed following axotomy. J Neurophysiol. 1994;72:466–470. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.72.1.466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yiangou Y, Facer P, Sinicropi DV, Boucher TJ, Bennett DL, McMahon SB, Anand P. Molecular forms of NGF in human and rat neuropathic tissues: decreased NGF precursor-like immunoreactivity in human diabetic skin. J Peripher Nerv Syst. 2002;7:190–197. doi: 10.1046/j.1529-8027.2002.02024.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]